SME Internationalization and Export Performance: A Systematic Review with Bibliometric Analysis

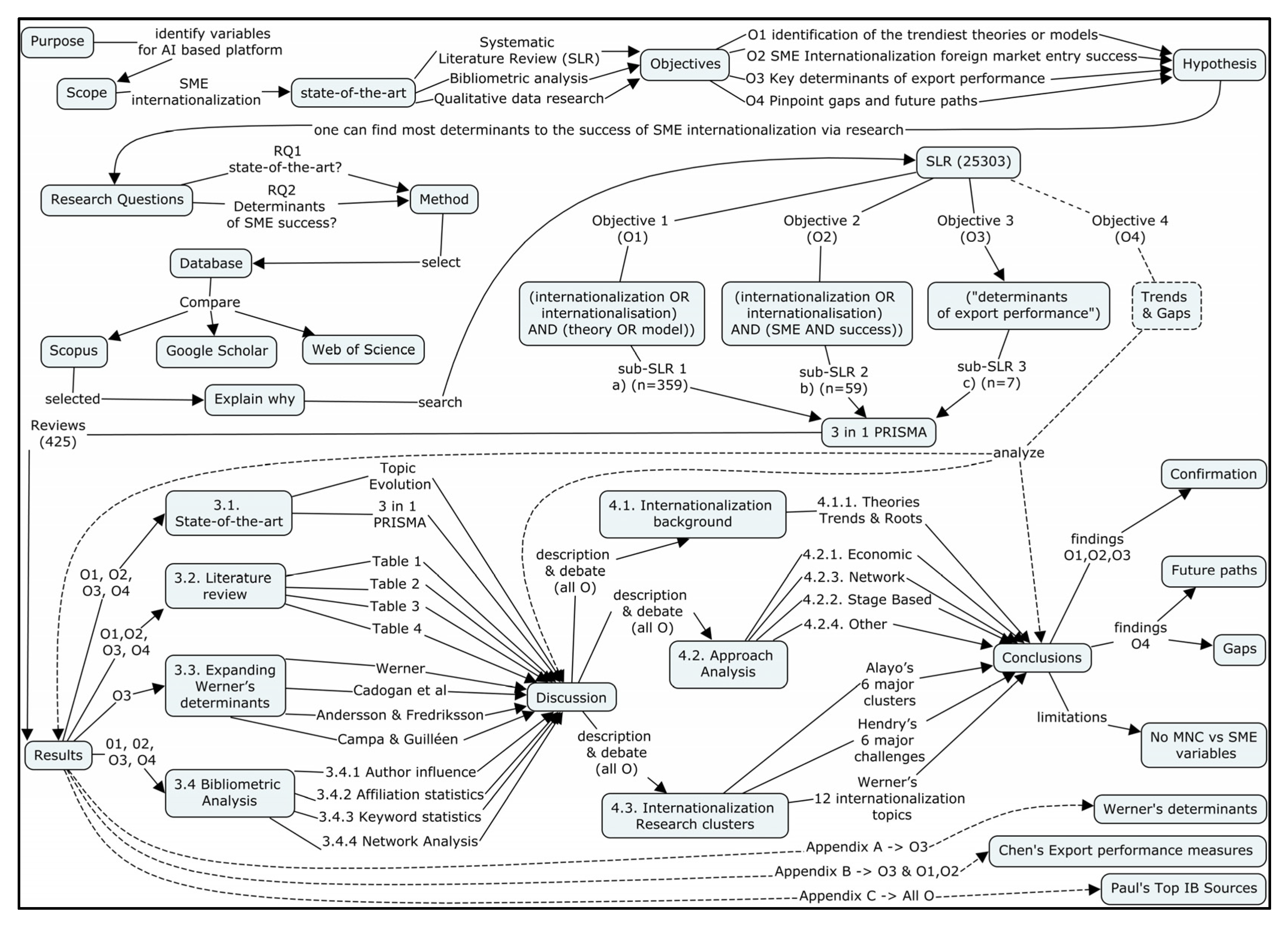

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

PRISMA (3 in 1)

3. Results

3.1. State-of-the-Art

Evolution of the Topic

3.2. Literature Review

3.3. Expanding Werner’s Determinants

3.4. Bibliometric Analysis

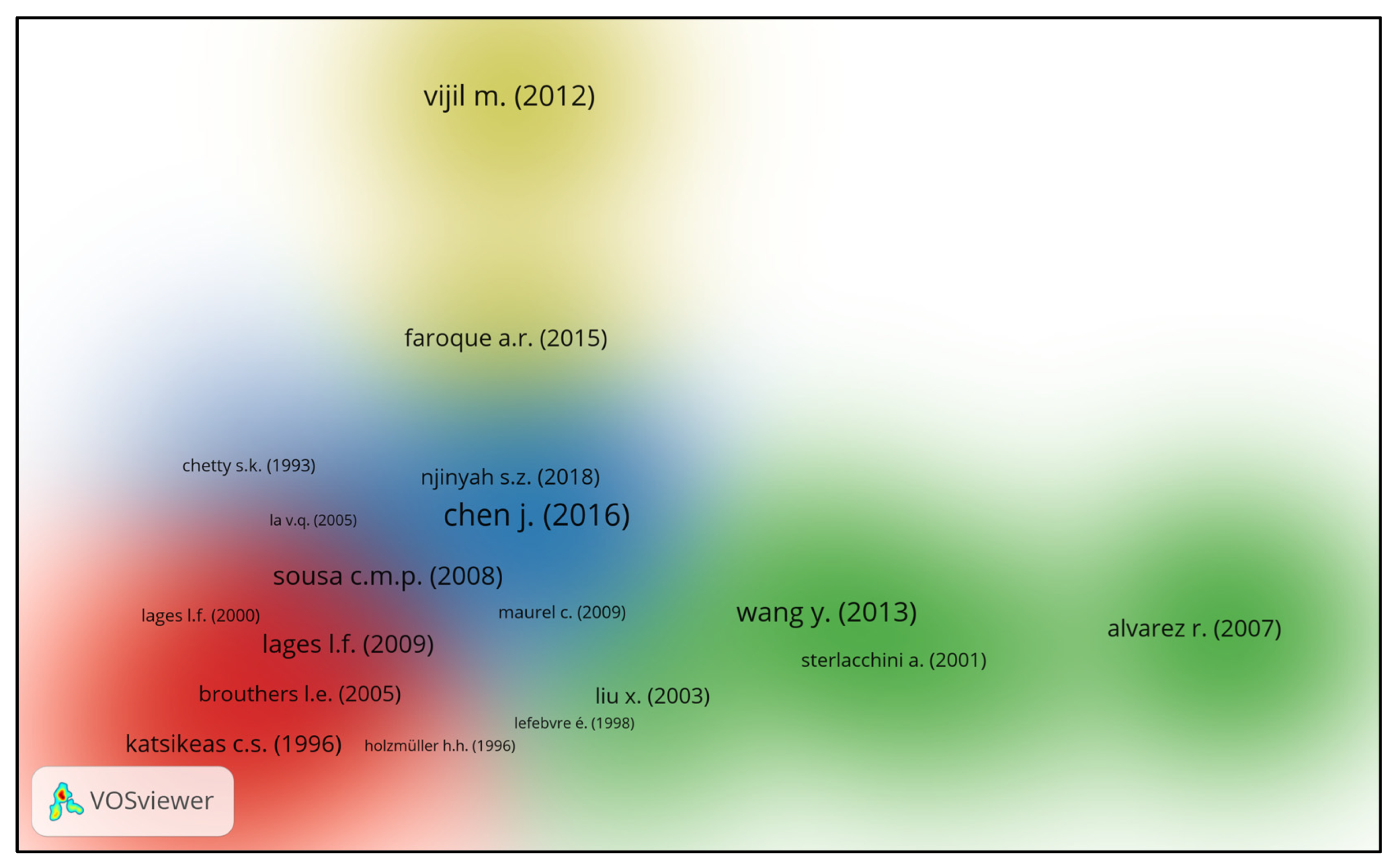

3.4.1. Author Influence

3.4.2. Affiliation Statistics

3.4.3. Keyword Statistics (via NVivo and VOSviewer)

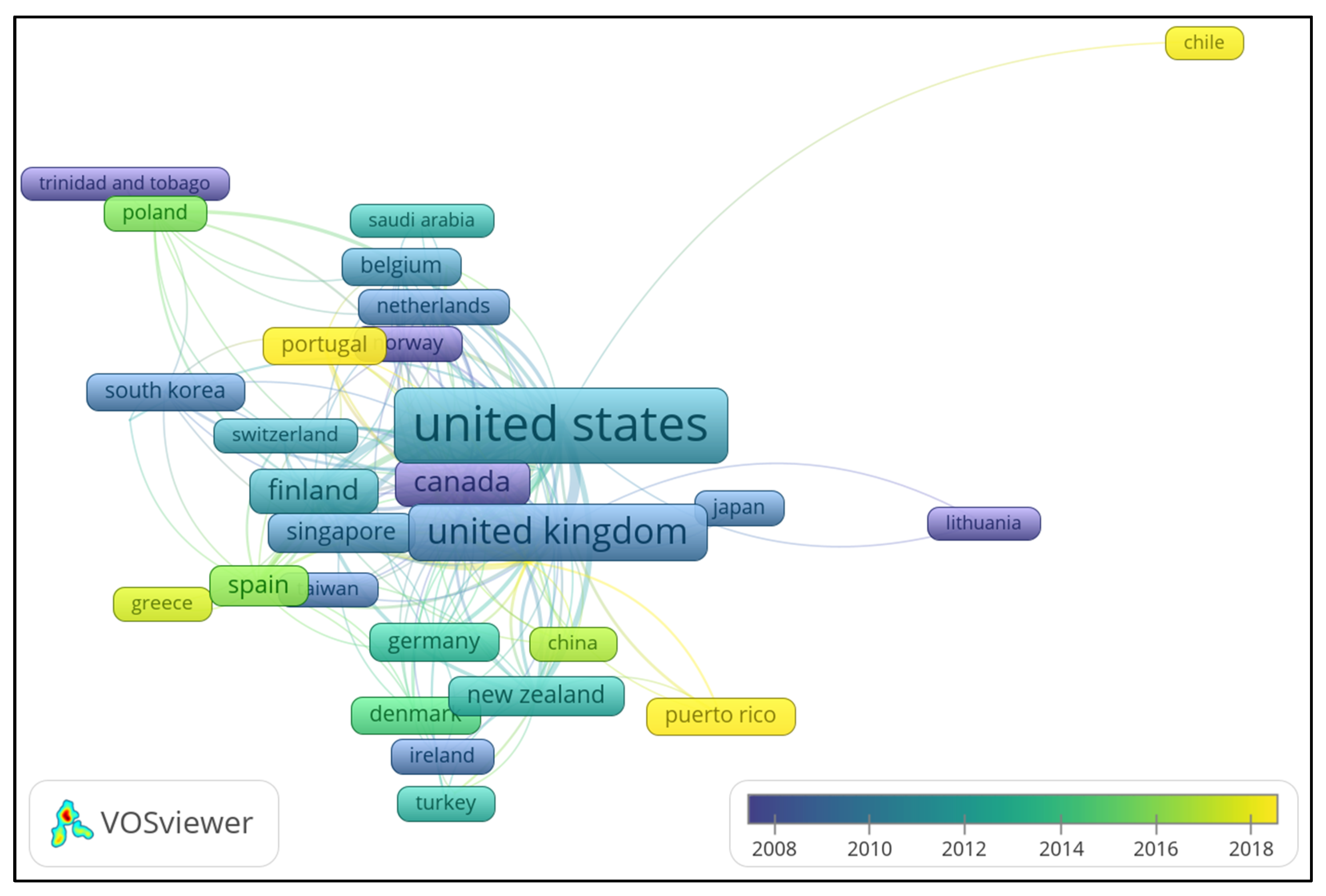

3.4.4. Network Analysis of Publications

4. Discussion

4.1. Internationalization Background

Theories (Trends and Roots)

- Attribution theory of internationalization

- Agency theory of internationalization

- Behavioral decision theory of internationalization

- Complexity theory of internationalization

- Critical theory of internationalization

- Decision theory of internationalization

- Deconstruction theory of internationalization

- Discourse theory of internationalization

- Equity theory of internationalization

- Evolutionary theory

- Exchange theory

- Masstige theory

- Prospect theory

- Technology acceptance model (TAM) of internationalization

- SCOPE framework

- Conservative, predictable, and pacemaker model (CPP model)

- Dynamic capability theory of internationalization

- Other important theories, already much debated

4.2. Approach Analysis

4.2.1. Economic Approach

- Diamond model

- Transaction cost theory

- Eclectic paradigm

4.2.2. Stage-Based Approach

- Product life cycle theory

- Uppsala model (U-model)

- Innovation-related model (I-model)

4.2.3. Network Approach

- Network theory model

4.2.4. Other Approaches

- The international entrepreneurship approach

- International new ventures (INVs) and the born global model

- Approaches that are not debated in this research

4.3. Internationalization Research Clusters

- Alayo’s six major clusters

- Hendry’s six major challenges

- Werner´s 12 internationalization topics

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Determinant |

|---|---|

| Description and Measurement | Process of Internationalization [39] |

| Measurement of globalization [224] | |

| Comment on measurement [225] | |

| Reply on measurement [226] | |

| Antecedents | Age, knowledge, and imitable [227] |

| Product diversification and performance [228] | |

| Privatization and network capabilities [229] | |

| Knowledge of International Business (IB) [230] | |

| Internationalization R&D intensity and sales [231] | |

| Information internationalization [232] | |

| Buyer and supplier entry and size [233] | |

| International experience, foreign partners and speed [234] | |

| Top management foreign experience [235] | |

| Industry factors and networks [236] | |

| Top management factors [237] | |

| Consequences | Advice network density [238] |

| Management team behavior and knowledge [239] | |

| CEO international experience [240] | |

| Performance, diversification, and time [241] | |

| Curvilinear performance effect [242] | |

| Performance cultural diversity [243] | |

| Performance and diversification moderator [244] | |

| MNE risk and leverage and market conditions [245] | |

| Performance and timing moderator [246] | |

| Performance, cultural distance, and experience moderators [247] | |

| Performance and timing of withdrawal [248] | |

| Firm valuation, investment, and incentives [249] | |

| Entrepreneurial firms [203] | |

| Performance and psychic distance moderator [250] | |

| Performance and cultural diversity [251] | |

| CEO pay and management team factors [252] | |

| Performance and expansion decisions [253] | |

| Performance and product diversity moderator [254] | |

| Performance and technological learning [255] |

| Category | Determinant |

|---|---|

| Predictors of Entry Mode Choice | Cultural distance and licensor competition [256] |

| Costs, cultural factors, and market structure [257] | |

| Transaction costs and strategic options [258] | |

| Firm structure, strategy, and country factors [259] | |

| Internal institutional pressures [260] | |

| Tech and characteristics of industry sectors [261] | |

| Target digestibility and industry growth [262] | |

| Digestibility and information asymmetry [263] | |

| Organizational capabilities and transaction costs [264] | |

| Transaction costs and national culture [265] | |

| Corporate visual identity [266] | |

| Experience with entry mode [267] | |

| Cooperative arrangements and risk sharing [268] | |

| Host, home, and industry factors, and mode hierarchy [269] | |

| Sequential pattern of entry [270] | |

| Industry and partner experience [271] | |

| Home, host industry, and operation factors [272] | |

| Predictors of Equity Ownership levels | Product and multinational diversity [273] |

| Institutional, cultural, and TC factors [274] | |

| Experience and institutional factors [228] | |

| Private and public expropriation hazards [275] | |

| Home national culture and economic factors [276] | |

| Firm specific advantages [277] | |

| Cultural distance and characteristics [278] | |

| Ownership, location, and internationalization factors [279] | |

| Consequences of Entry Mode | Performance, firm capabilities, and mode fit [280] |

| Longevity and cultural distance [281] | |

| Responses environment change [282] | |

| Performance, ILO and mode fit [283] | |

| Performance, strategy, and mode fit [284] |

| Category | Determinant |

|---|---|

| Exchange Overviews | Types of exchanges and their enforcement [285] |

| Integrating importing/exporting decisions [286] | |

| Effect of lagging adjustments and social networks [287] | |

| Determinants of exporting | Market size, income, size, and imports [37] |

| Market orientation [36] | |

| Home/host location factors and ownership advantages [38] | |

| Existing interpersonal links [64] | |

| Review of process and determinants [65] | |

| Export Intermediaries | Service offerings, size, role, suppliers, and products [288] |

| Performance, market distance, and products [289] | |

| Use, products, and market distance/familiarity [290] | |

| Consequences of exporting | Export performance and strategic fit [291] |

| Export ratio and keiretsu membership [17] | |

| Export ratio, firm performance, market share, and size [292] | |

| Export and economic performance and gray market activity [293] |

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green Supply Chain Management: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayo, M.; Iturralde, T.; Maseda, A.; Aparicio, G. Mapping Family Firm Internationalization Research: Bibliometric and Literature Review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 1517–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, R. Advancing Research on the Determinants of Indian MNEs: The Role of Sub-National Institutions. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 13, 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Chu, W. The Determinants of Trust in Supplier-Automaker Relationships in the US, Japan, and Korea. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Caves, R.E. Uncertain Outcomes of Foreign Investment: Determinants of the Dispersion of Profits after Large Acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Balkin, D.B. Determinants of Faculty Pay: An Agency Theory Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 921–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, I.R.P.; Patel, C.; Ertug, G.; Li, J.; Cuypers, Y. Top Management Teams in International Business Research: A Review and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 53, 481–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennart, J.-F.; Majocchi, A.; Forlani, E. The Myth of the Stay-at-Home Family Firm: How Family-Managed SMEs Can Overcome Their Internationalization Limitations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 758–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuber, A.R.; Knight, G.A.; Liesch, P.W.; Zhou, L. International Entrepreneurship: The Pursuit of Entrepreneurial Opportunities across National Borders. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, A.; Strange, R.N.; Mascherpa, S. Which Organisational Capabilities Matter for SME Export Performance? Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2019, 13, 454–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.M.P.; Martínez-López, F.J.; Coelho, F. The Determinants of Export Performance: A Review of the Research in the Literature between 1998 and 2005. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 343–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla-Barber, J.; Alegre, J. Analysing the Link between Export Intensity, Innovation and Firm Size in a Science-Based Industry. Int. Bus. Rev. 2007, 16, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majocchi, A.; Bacchiocchi, E.; Mayrhofer, U. Firm Size, Business Experience and Export Intensity in SMEs: A Longitudinal Approach to Complex Relationships. Int. Bus. Rev. 2005, 14, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Samiee, S. Marketing Strategy Determinants of Export Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Leonidou, L.C.; Morgan, N.A. Firm-Level Export Performance Assessment: Review, Evaluation, and Development. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, G.; Jacobson, C.K. The Effects of the Keiretsu on the Export Performance of Japanese Companies: Help or Hindrance? Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, E.; Stein, S. What Counts as Internationalization? Deconstructing the Internationalization Imperative. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2020, 24, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzigeorgiou, A.; Lodefalk, M. A Literature Review of the Nexus between Migration and Internationalization. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2021, 30, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer: A Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–17 July 2009; pp. 886–897. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, C.; Silverstein, L.B. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. In Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 1–202. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, L. Data Alive! The Thinking behind NVivo. Qual. Health Res. 1999, 9, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sousa, C.M.P.; He, X. The Determinants of Export Performance: A Review of the Literature 2006–2014. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 626–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N.; Pandey, N. Research Published in Management International Review from 2006 to 2020: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Directions. Manag. Int. Rev. 2021, 61, 599–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Singh, S.; Dhir, S. Culture and International Business Research: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Paul, J.; Chavan, M. Internationalization Barriers of SMEs from Developing Countries: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1281–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Falahat, M. The Impact of Digitalization and Resources on Gaining Competitive Advantage in International Markets: Themediating Role Ofmarketing, Innovation and Learning Capabilities. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rosado-Serrano, A. Gradual Internationalization vs. Born-Global/International New Venture Models: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 830–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari Sadeghi, V.; Biancone, P.P. How Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Are Driven Outward the Superior International Trade Performance? A Multidimensional Study on Italian Food Sector. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2018, 45, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowski, B.; Kekec, P.; Morgan, N.A.; Hult, G.T.M.; Walkowiak, T.; Runnalls, B. An Assessment of the Exporting Literature: Using Theory and Data to Identify Future Research Directions. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 118–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaubourg, A.-G. Finance and International Trade: A Review of the Literature. Rev. Econ. Polit. 2016, 126, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribau, C.P.; Moreira, A.C.; Raposo, M. SME Internationalization Research: Mapping the State of the Art: SME Internationalization Research: Mapping the State of the Art. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Adm. 2018, 35, 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribau, C.P.; Moreira, A.C.; Raposo, M. SMEs Innovation Capabilities and Export Performance: An Entrepreneurial Orientation View. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, L.; Poncet, S. Environmental Policy and Exports: Evidence from Chinese Cities. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 68, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S. Recent Developments in International Management Research: A Review of 20 Top Management Journals. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadogan, J.W.; Diamantopoulos, A.; De Mortanges, C.P. A Measurement of Export Market Orientation: Scale Development and Cross-Cultural Validation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Fredriksson, T. International Organization of Production and Variation in Exportation from Affiliates. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, J.M.; Guilléen, M.F. The Internationalization of Exports: Firm- and Location-Specific Factors in a Middle-Income Country. Manag. Sci. 1999, 45, 1463–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, C. Continuities in Human Resource Processes in Internationalization and Domestic Business Management. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.-W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A Longitudinal and Cross-Disciplinary Comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaanse, L.S.; Rensleigh, C. Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar a Content Comprehensiveness Comparison. Electron. Libr. 2013, 31, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; Delgado López-Cózar, E. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A Systematic Comparison of Citations in 252 Subject Categories. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviatt, B.M.; McDougall, P.P. Defining International Entrepreneurship and Modeling the Speed of Internationalization; Blackwell Publishing Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. A Dynamic Capabilities-Based Entrepreneurial Theory of the Multinational Enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. A Theory of International New Ventures: A Decade of Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Knight, G. The Born Global Firm: An Entrepreneurial and Capabilities Perspective on Early and Rapid Internationalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delios, A.; Henisz, W.J. Political Hazards, Experience, and Sequential Entry Strategies: The International Expansion of Japanese Firms, 1980–1998. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Parthasarathy, S.; Gupta, P. Exporting Challenges of SMEs: A Review and Future Research Agenda. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazurra, A.C.; Inkpen, A.; Musacchio, A.; Ramaswamy, K. Governments as Owners: State-Owned Multinational Companies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 919–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannen, M.Y. When Mickey Loses Face: Recontextualization, Semantic Fit, and the Semiotics of Foreignness. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E. Creative Tension: The Significance of Ben Oviatt’s and Patricia McDougall’s Article “Toward a Theory of International New Ventures”. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummela, N.; Saarenketo, S.; Puumalainen, K. A Global Mindset—A Prerequisite for Successful Internationalization? Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2004, 21, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.A.; Pett, T.L. Small-Firm Performance: Modeling the Role of Product and Process Improvements. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H. Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Grounded Theoretical Framework and an Overview. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2004, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, A.; Krist, M. The Effect of Context-Related Moderators on the Internationalization-Performance Relationship: Evidence from Meta-Analysis. Manag. Int. Rev. 2007, 47, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, A.; Abimbola, T. The Effects of Entrepreneurial Marketing on Born Global Performance. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luostarinen, R.; Gabrielsson, M. Globalization and Marketing Strategies of Born Globals in SMOPECs. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2006, 48, 773–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, L.E.; Nakos, G. The Role of Systematic International Market Selection on Small Firms’ Export Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valos, M.; Baker, M. Developing an Australian Model of Export Marketing Performance Determinants. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1996, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysen, T. Towards a Framework for Controls as Determinants of Export Performance: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Literature 1995–2011. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, M.U.D.; Ghani, E.; Mahmood, T. Determinants of Export Performance of Pakistan: Evidence from the Firm-Level Data. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2009, 48, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, J. The Determinants of Export Performance of Developing Countries. J. Econ. Stud. 1982, 9, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P.D. Social Ties and Foreign Market Entry. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Katsikeas, C.S. The Export Development Process: An Integrative Review of Empirical Models. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 517–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. Market Orientation and Customer Service: The Implications For Business Performance. In E—European Advances in Consumer Research; Van Raaij, W.F., Bamossy, G.J., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Martinko, M.J.; Mackey, J.D. Attribution Theory: An Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, P.; Madison, K.; Martinko, M.; Crook, T.; Crook, T. Attribution Theory in the Organizational Sciences: The Road Traveled and the Path Ahead. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.I. Attribution Theory Revisited: Probing the Link Among Locus of Causality Theory, Destination Social Responsibility, Tourism Experience Types, and Tourist Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cort, K.T.; Griffith, D.A.; Steven White, D. An Attribution Theory Approach for Understanding the Internationalization of Professional Service Firms. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.; Lane, P.J.; Collin, S.; Very, P. An Embeddedness Framing of Governance and Opportunism: Towards a Cross-Nationally Accommodating Theory of Agency. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.M. Explaining International Retailers’ Market Entry Mode Strategy: Internalization Theory, Agency Theory and the Importance of Information Asymmetry. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 1999, 9, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. An Embeddedness Framing of Governance and Opportunism: Towards a Cross-Nationally Accommodating Theory of Agency—Critique and Extension. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.; O’Donnell, S.W. Foreign Subsidiary Compensation Strategy: An Agency Theory Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 678–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, H.J.; Hogarth, R.M. Behavioral Decision Theory: Processes of Judgement and Choice. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1981, 32, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Fischhoff, B.; Lichtenstein, S. Behavioral Decision Theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1977, 28, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.E.; Liesch, P.W. Wait-and-See Strategy: Risk Management in the Internationalization Process Model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.S.; Mani, V.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Shi, Y. Behavioral Mechanisms Influencing Sustainable Supply Chain Governance Decision-Making from a Dyadic Buyer-Supplier Perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 236, 108136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Sramek, B.; Thomas, R.W.; Fugate, B.S. Integrating Behavioral Decision Theory and Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Prioritizing Economic, Environmental, and Social Dimensions in Carrier Selection. J. Bus. Logist. 2018, 39, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sahoo, S.; Lim, W.M.; Kraus, S.; Bamel, U. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (FsQCA) in Business and Management Research: A Contemporary Overview. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 178, 121599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-L.; Yeh, S.-S.; Huan, T.C.; Woodside, A.G. Applying Complexity Theory to Deepen Service Dominant Logic: Configural Analysis of Customer Experience-and-Outcome Assessments of Professional Services for Personal Transformations. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1647–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenhead, J.; Franco, L.A.; Grint, K.; Friedland, B. Complexity Theory and Leadership Practice: A Review, a Critique, and Some Recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina Cunha, M.; Vieira Cunha, J. Towards a Complexity Theory of Strategy. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, V.J. The Development of International Industry Clusters: A Complexity Theory Approach. J. Int. Entrep. 2005, 3, 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Baker, R.M. Review Complexity Theory: An Overview with Potential Applications for the Social Sciences. Systems 2019, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, E.R.; Ciravegna, L.; Woodside, A.G. Taking the Complexity Turn in Strategic Management Theory and Research. In The Complexity Turn: Cultural, Management, and Marketing Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 21–66. ISBN 9783319470283. [Google Scholar]

- Overall, J. All around the Mulberry Bush: A Theory of Cyclical Unethical Behaviour. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2018, 20, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, D. Stakeholder Management Theory: A Critical Theory Perspective. Bus. Ethics Q. 1999, 9, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, D. Employing Normative Stakeholder Theory in Developing Countries: A Critical Theory Perspective. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 166–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W. Rethinking the Mission of Internationalization of Higher Education in the Asia-Pacific Region. Compare 2012, 42, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwil, F. Looking Back from Somewhere: Reflections on What Remains ‘Critical’ in Critical Theory. Rev. Int. Stud. 2007, 33, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.T.; Bohoris, G. Decision Theory in Maintenance Decision Making. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 1995, 1, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Walker, H.; Naim, M. Decision Theory in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Kumar, M.; Walker, H. A Decision Theory Perspective on Complexity in Performance Measurement and Management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 2214–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nemkova, E.; Souchon, A.L.; Hughes, P.; Micevski, M. Does Improvisation Help or Hinder Planning in Determining Export Success? Decision Theory Applied to Exporting. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.O. An Assessment of the Conceptual Linkages between the Qualitative Characteristics of Useful Financial Information and Ethical Behavior within Informal Institutions. Econ. Horiz. 2020, 22, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, J.; Newenham-Kahindi, A.; Patnaik, S. Trevino and Doh’s Discourse-Based View: Do We Need a New Theory of Internationalization? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1394–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.J.; Doh, J.P. Internationalization of the Firm: A Discourse-Based View. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1375–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.A.; David, P.; Shao, F.; Fox, C.J.; Westermann-Behaylo, M. An Examination of the Impact of Executive Compensation Disparity on Corporate Social Performance. Strateg. Organ. 2015, 13, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.A.; Ali, M.Y.; Quazi, A.; Wickramasekera, R. A Critical Appraisal of the Relational Management Paradigm in an International Setting: A Future Research Agenda. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 268–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, W. How CEO Underpayment Influences Strategic Change: The Equity Perspective. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 2277–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees-Buss, J.; Welch, C.; Westney, D.E. What Happened to the Transnational? The Emergence of the Neo-Global Corporation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1513–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.D.; Meyer, K.E. Internationalization as an Evolutionary Process. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.D.; Stucchi, T. Internationalization through Exaptation: The Role of Domestic Geographical Dispersion in the Internationalization Process. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparaocha, G.O. Towards Building Internal Social Network Architecture That Drives Innovation: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizanti, I.; Lerner, M. Examining Control and Autonomy in the Franchisor-Franchisee Relationship. Int. Small Bus. J. 2003, 21, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Xu, D. How Foreign Firms Curtail Local Supplier Opportunism in China: Detailed Contracts, Centralized Control, and Relational Governance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Saha, V.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Kalai, A.; Debnath, N. Cultural Consequences of Brands’ Masstige: An Emerging Market Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Saha, V.; Roy, A. Inspired and Engaged: Decoding MASSTIGE Value in Engagement. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Paul, J. Mass Prestige Value and Competition between American versus Asian Laptop Brands in an Emerging Market—Theory and Evidence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J. Masstige Marketing Redefined and Mapped: Introducing a Pyramid Model and MMS Measure. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J. Toward a “masstige” Theory and Strategy for Marketing. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 12, 722–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.C.; Bansal, P. How Firm Performance Affects Internationalization. Manag. Int. Rev. 2009, 49, 709–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, R.; Whitler, K.A.; Semadeni, M. Power to the Principals! An Experimental Look at Shareholder Say-on-Pay Voting. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yi, X.; Cui, G. Emerging Market Firms’ Internationalization: How Do Firms’ Inward Activities Affect Their Outward Activities? Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2704–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, E.; Beamish, P.W. The Accentuated CEO Career Horizon Problem: Evidence from International Acquisitions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rosenbaum, M. Retailing and Consumer Services at a Tipping Point: New Conceptual Frameworks and Theoretical Models. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation. Long Range Plann. 2017, 50, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, A.; Lagerström, K.; Sallis, J. Turning the Tables: The Relationship Between Performance and Multinationality. Manag. Int. Rev. 2022, 62, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyo, P.K.; Osabutey, E.L.C. Unearthing Antecedents to Financial Inclusion through FinTech Innovations. Technovation 2020, 98, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasingh, S.; Eze, U.C. An Empirical Analysis of Consumer Behavioural Intention Towards Mobile Coupons in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2009, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N. Using the Technology Acceptance Model to Explain How Attitudes Determine Internet Usage: The Role of Perceived Access Barriers and Demographics. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, A.; Paul, J.; Kaurav, R.P.S. Determinants of Mobile Apps Adoption among Young Adults: Theoretical Extension and Analysis. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höflich, J.R.; Rössler, P. Mobile Written Communication Or: E-mail for the Mobile. The Importance of Electronic Short Messages (Short Message Service) Using the Example of Young Mobile Phone Users. M K Media Commun. Sci. 2001, 49, 437–461. [Google Scholar]

- Fourati-Jamoussi, F.; Niamba, C.-N.; Duquennoy, J. An Evaluation of Competitive and Technological Intelligence Tools: A Cluster Analysis of Users’ Perceptions. J. Intell. Stud. Bus. 2018, 8, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-Y.; Cruickshank, D.; Anderson, A.R. The Adoption of E-Trade Innovations by Korean Small and Medium Sized Firms. Technovation 2009, 29, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J. SCOPE Framework for SMEs: A New Theoretical Lens for Success and Internationalization. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avioutskii, V.; Tensaout, M. Comparative Analysis of FDI by Indian and Chinese MNEs in Europe. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 32, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Ni, P.; Reve, T.; Huang, J.; Lu, R. Sales Growth or Employment Growth? Exporting Conundrum for New Ventures. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2020, 31, 482–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Sánchez-Morcilio, R. Toward A New Model For Firm Internationalization: Conservative, Predictable, and Pacemaker Companies and Markets. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2019, 36, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Evers, N. International Opportunity Recognition in International New Ventures—A Dynamic Managerial Capabilities Perspective. J. Int. Entrep. 2015, 13, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocconcelli, R.; Cioppi, M.; Fortezza, F.; Francioni, B.; Pagano, A.; Savelli, E.; Splendiani, S. SMEs and Marketing: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Seth, A. A Dynamic Model of the Choice of Mode for Exploiting Complementary Capabilities. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, N. International New Ventures in “Low Tech” Sectors: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2011, 18, 502–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Strategic Flexibility and International Venturing by Emerging Market Firms: The Moderating Effects of Institutional and Relational Factors. J. Int. Mark. 2013, 21, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susman, G.I. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and the Global Economy. Young Al 2007, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calof, J.L.; Beamish, P.W. Adapting to Foreign Markets: Explaining Internationalization. Int. Bus. Rev. 1995, 4, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; Alex Catalogue: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, B. International Economics: A European Focus; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-273-65507-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, E.K. History of Economic Thought: A Critical Perspective; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-7656-0607-0. [Google Scholar]

- Isard, W. Location Theory and Trade Theory: Short-Run Analysis. Q. J. Econ. 1954, 68, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. Specific Factors and Heckscher–Ohlin: An Intertemporal Blend. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2007, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaug, M. The Methodology of Economics, or, How Economists Explain; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 0-521-43678-8. [Google Scholar]

- Heckscher, E. The Effect of Foreign Trade on the Distribution of Income. Ekon. Tidskriff 1919, 21, 497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Leontief, W. Domestic production and foreign trade; the American capital position re-examined. Econ. Internazionale 1954, 7, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, S. An Essay on Trade and Transformation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Dicken, P.; Lloyd, P.E. Location in Space: Theoretical Perspectives in Economic Geography; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, B.J.; Neils, E. Location, Size and Shape of Cities as Influenced by Environmental Factors: The Urban Environment Writ Large; Routledge: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Isard, W. Location and Space-Economy; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.M.; Erramilli, M.K. Resource-Based Explanation of Entry Mode Choice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2004, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, R.E. Research on International Business: Problems and Prospects. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H.; Rugman, A.M. The Influence of Hymer’s Dissertation on the Theory of Foreign Direct Investment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Caves, R.E. International Corporations: The Industrial Economics of Foreign Investment. Economica 1971, 38, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindleberger, C.P. American Business Abroad: Six Lectures on Direct Investment; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hymer, S.H. The International Operations of National Firms, a Study of Direct Foreign Investment. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P.; Wells, R. Economics; Worth Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P.R. The Narrow and Broad Arguments for Free Trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.; Norman, V. Theory of International Trade: A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Competitive Strategy Techniques for Analyzing Industries And Competitors; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C. Porter’s Diamond Approaches and the Competitiveness Web. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 10, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The Nature of the Firm. Economica 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Transaction Cost Economics Project: Origins, Evolution, Utilization. In The Elgar Companion to Ronald H. Coase; Menard, C., Bertrand, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.H. The Eclectic (OLI) Paradigm of International Production: Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2001, 8, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, L.; Dai, L. Rethinking the O in Dunning’s OLI/Eclectic Paradigm. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2010, 18, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, N.E.; McAuley, A. Internationalisation and the Smaller Firm: A Review of Contemporary Empirical Research. MIR Manag. Int. Rev. 1999, 39, 223–256. [Google Scholar]

- Stremtan, F.; Mihalache, S.-S.; Pioras, V. On the Internationalization of the Firms-from Theory to Practice. Ann. Univ. Apulensis Ser. Oeconomica 2009, 11, 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Melin, L. Internationalization as a Strategy Process. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J. Pricing Policies for New Products. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1950, 28, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, T. Exploit the Product Life Cycle; Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; Volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, A. Stretch Your Product’s Earning Years: Top Management’s Stake in the Product Life Cycle. Manag. Rev. 1959, 48, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J. Industrial Dynamics: A Major Breakthrough for Decision Makers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1958, 36, 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Polli, R.; Cook, V. Validity of the Product Life Cycle. J. Bus. 1969, 42, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, W.E. Product Life Cycles as Marketing Models. J. Bus. 1967, 40, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, R. International Investment and International Trade in the Product Cycle. Q. J. Econ. 1966, 80, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. The Internationalization Process of the Firm: A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1977, 8, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. The Mechanism of Internationalisation. Int. Mark. Rev. 1990, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, S.; Houlden, J. Decision-Making and Market Orientation in the Internationalization Process of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 413–436. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzier, M.; Antoncic, B.; Hisrich, R.D.; Konecnik, M. Human Capital and SME Internationalization: A Structural Equation Modeling Study. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2007, 24, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, T.K. Critical Success Factors of SME Internationalization. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2016, 26, 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Belso-Martínez, J.A. Why Are Some Spanish Manufacturing Firms Internationalizing Rapidly? The Role of Business and Institutional International Networks. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2006, 18, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. Commitment and Opportunity Development in the Internationalization Process: A Note on the Uppsala Internationalization Process Model. Manag. Int. Rev. 2006, 46, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.E. The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model Revisited: From Liability of Foreignness to Liability of Outsidership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1411–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanaraj, C.; Beamish, P.W. A Resource-Based Approach to the Study of Export Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2003, 41, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkey, W.J.; Tesar, G. The Export Behavior of Smaller-Sized Wisconsin Manufacturing Firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1977, 8, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T. On the Internationalization Process of Firms. Eur. Res. 1980, 8, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Czinkota, M.R. Export Development Strategies: US Promotion Policy; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 151. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.D. The Decision-Maker and Export Entry and Expansion. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1981, 12, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O. On the Internationalization Process of Firms: A Critical Analysis. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1993, 24, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Mattsson, L.-G. International Marketing and Internationalization Processes—A Network Approach Jan Johanson and Lars Gunnar—Mattsson University of Uppsala and Stockholm School of Economics. Res. Int. Mark. 1986, 234–252. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=pt-PT&lr=&id=e_yYUxC8t3oC&oi=fnd&pg=PA234&ots=P3TB3NkOdo&sig=m4_GV35A14Jvq8NWlStURgX4cgA (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Blankenburg Holm, D.; Eriksson, K.; Johanson, J. Creating Value through Mutual Commitment to Business Network Relationships. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S.; Blankenburg Holm, D. Internationalisation of Small to Medium-Sized Manufacturing Firms: A Network Approach. Int. Bus. Rev. 2000, 9, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H. SME’ Internationalization Strategies Based on a Typical Subsidiary Evolutionary Life Cycle in Three Distinct Stages”. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 145–186. [Google Scholar]

- Laghzaoui, S. SMEs’ Internationalization: An Analysis with the Concept of Resources and Competencies. J. Innov. Econ. 2011, 7, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, M. A Note on the Revisited Uppsala Internationalization Process Model—The Implications of Business Networks and Entrepreneurship. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2016, 47, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, M.; Holm, U.; Johanson, J. Managing the Embedded Multinational: A Business Network View; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, R.D.; Wilson, H.I.M. The Network Model of Internationalisation and Experiential Knowledge. Int. Bus. Rev. 2003, 12, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P.P.; Oviatt, B.M. International Entrepreneurship: The Intersection of Two Research Paths. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.V.; Coviello, N.; Tang, Y.K. International Entrepreneurship Research (1989–2009): A Domain Ontology and Thematic Analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 632–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzier, M.; Hisrich, R.D.; Antoncic, B. SME Internationalization Research: Past, Present, and Future. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Dimitratos, P.; Dana, L.-P. International Entrepreneurship Research: What Scope for International Business Theories? J. Int. Entrep. 2003, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.-J.; Kim, D.; Cavusgil, E. Antecedents and Outcomes of Digital Platform Risk for International New Ventures’ Internationalization. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Evers, N.; Kuivalainen, O. International New Ventures: Rapid Internationalization across Different Industry Contexts. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, D.; Musteen, M.; Thomas, D.E. International New Ventures: The Cross-Border Nexus of Individuals and Opportunities. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P.P.; Shane, S.; Oviatt, B.M. Explaining the Formation of International New Ventures: The Limits of Theories from International-Business Research. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.A.; Cavusgil, S.T. Innovation, Organizational Capabilities, and the Born-Global Firm. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.A.; Liesch, P.W. Internationalization: From Incremental to Born Global. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, F.J.; Jones, M.V. Speed of Internationalization and Entrepreneurial Cognition: Insights and a Comparison between International New Ventures, Exporters and Domestic Firms. J. World Bus. 2007, 42, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keupp, M.M.; Gassmann, O. The Past and the Future Ofinternational Entrepreneurship: A Review and Suggestions Fordeveloping the Field. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 600–633. [Google Scholar]

- Mainela, T.; Puhakka, V.; Servais, P. The Concept of International Opportunity in International Entrepreneurship: Areview and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.A.; Zander, I. The International Entrepreneurial Dynamics of Accelerated Internationalisation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, N. Re-Thinking Research on Born Globals. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, I.; McDougall-Covin, P.; L Rose, E. Born Globals and International Business: Evolution of a Field of Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M.; Knight, G.; Alon, I. Orientations and Capabilities of Born Global Firms from Emerging Markets”. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 936–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayo, M.; Maseda, A.; Iturralde, T.; Arzubiaga, U. Internationalization and Entrepreneurial Orientation of Family SMEs: The Influence of the Family Character. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, Ø.; Rialp, A.; Rialp, J. Examining the Importance of Social Media and Other Emerging ICTs in Far Distance Internationalisation: The Case of a Western Exporter Entering China. Int. Bus. Emerg. Econ. Firms Vol. Univers. Issues Chin. Perspect. 2020, 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Johanson, M. Speed and Synchronization in Foreign Market Network Entry: A Note on the Revisited Uppsala Model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1628–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros-Lobo, N.; Ferreira, J.V.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. The SUPWAVE Theory of International Marketing: An Analogy between Catching the Best Waves and Foreign Market Entry Decisions. ICIEMC Proc. 2021, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhija, M.V.; Kim, K.; Williamson, S.D. Measuring Globalization of Industries Using a National Industry Approach: Empirical Evidence across Five Countries and over Time. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 679–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, K.; Kroeck, K.G.; Renforth, W. Measuring the Degree of Internationalization of a Firm: A Comment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D. Measuring the Degree of Internationalization Ofa Firm: A Reply. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Sapienza, H.J.; Almeida, J.G. Effects of Age at Entry, Knowledge Intensity, and Imitability on International Growth. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delios, A.; Beamish, P.W. Geographic Scope, Product Diversification, and the Corporate Performance of Japanese Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P. Entrepreneurial Privatization Strategies: Order of Entry and Local Partner Collaboration as Source of Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Johanson, J.; Majkgård, A.; Sharma, D.D. Experiential Knowledge and Cost in the Internationalization Process. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegenbaum, A.; Shaver, J.M.; Yeung, B. Which Firms Expand to the Middle East: The Experience of US Multinationals. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesch, P.W.; Knight, G.A. Information Internationalization and Hurdle Rates in Small and Medium Enterprise Internationalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, X.; Swaminathan, A.; Mitchell, W. Organizational Evolution in the Interorganizational Environment: Incentives and Constraints on International Expansion Strategy. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuber, A.R.; Fischer, E. The Influence of the Management Team’s International Experience on the Internationalization Behaviors of SMEs. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambharya, R.B. Foreign Experience of Top Management Teams and International Diversification Strategies of U.S. Multinational Corporations. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.B.; Cavusgil, S.T.; Aulakh, P.S. International Expansion of Telecommunication Carriers: The Influence of Market Structure, Network Characteristics, and Entry Imperfections. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihanyi, L.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Daily, C.M.; Dalton, D.R. Composition of the Top Management Team and Firm International Diversification. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1157–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, N.; Nigh, D. The Impact of US Company Internationalization on Top Management Team Advice Networks: A Tacit Knowledge Perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, N.; Nigh, D. Internationalization, Tacit Knowledge and the Top Management Team of MNCs. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 3, 471487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.M.; Certo, S.T.; Dalton, D.R. International Experience in the Executive Suite: Path to Prosperity? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geringer, J.M.; Tallman, S.; Olsen, D.M. Product and International Diversification among Japanese Multinational Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Ramaswamy, K. An Empirical Examination of the Form of the Relationship between Multinationality and Performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Palich, L.E. Cultural Diversity and the Performance of Multinational Firms. J. Int. Stud. 1997, 28, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Hoskisson, R.E.; Kim, H. International Diversification: Effects on Innovation and Firm Performance in Product-Diversified Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 767–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.C.K.; Reeb, D.M. Internationalization and Firm Risk: An Upstream-Downstream Hypothesis. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Timing of Investment and International Expansion Performance in China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Time-Based Experience and International Expansion: The Case of an Emerging Economy. J. Manag. Stud. 1999, 36, 505–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meznar, M.B.; Nigh, D.; Kwok, C.C.Y. Announcements of Withdrawal from South Africa Revisited: Marking Sense of Contradictory Event Study Findings. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, C.S.; Gobeli, D.H. Managerial Incentives, Internalization and Market Valuation of Multinational Firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’grady, S.; Lane, H.W. The Psychic Distance Paradox. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palich, L.E.; Gomez-Mejia, L.E. A Theory of Global Strategy and Firm Efficiencies: Considering the Effects of Cultural Diversity. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.G.; Carpenter, M.A. Internationalization and Firm Governance: The Roles of CEO Compensation, Top Team Composition, and Board Structure. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syam, S.S. Multiperiod capacity expansion in globally dispersed regions. Decis. Sci. 2000, 31, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallman, S.; Li, J. Effects of International Diversity and Product Diversity on the Performance of Multinational Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A. International Expansion by New Venture Firms: International Diversity, Mode of Market Entry, Technological Learning, and Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 925–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Fosfuri, A. Wholly Owned Subsidiary vs. Technology Licensing in the Worldwide Chemical Industry. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J.; Casson, M. Models of the Multinational Enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; McGuire, D.J. Collaborative Ventures and Value of Learning: Integrating the Transaction Cost and Strategic Option Perspectives on the Choice of Market Entry Modes. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, F.J.; Kundu, S.K. Modal Choice in a World of Alliances: Analyzing Organizational Forms in the International Hotel Sector. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 325–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.S.; Desai, A.B.; Francis, J.D. Mode of International Entry: An Isomorphism Perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, J.; Narula, R. Choosing Organizational Modes of Strategic Technology Partnering: International and Sectoral Differences. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennart, J.; Reddy, S. The Choice between Mergers/Acquisitions and Joint Ventures: The Case of Japanese Investors in the United States. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennart, J.; Reddy, S. Digestibility and Asymmetric Information in the Choice between Acquisitions and Joint Ventures: Where’s the Beef? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, A. Cost, Value and Foreign Market Entry Mode: The Transaction and the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, S.; Neupert, K.E. National Culture, Transaction Costs, and the Choice between Joint Venture and Wholly Owned Subsidiary. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T.C.; Saunders, J. International Corporate Visual Identity: Standardization or Localization? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, P.; Cho, K.R. Decision Specific Experience in Foreign Ownership and Establishment Strategies: Evidence from Japanese Firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Tse, D.K. The Impact of Order and Mode of Market Entry on Profitability and Market Share. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Tse, D.K. The Hierarchical Model of Market Entry Modes. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner-Hahn, J.D. Firm and Environmental Influences on the Mode and Sequence of Foreign Research and Development Activities. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, P.F.; Ettlie, J.E. U.S.-Japanese Manufacturing Equity Relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, D.K.; Pan, Y.; Au, K.Y. How MNCS Choose Entry Modes and Form Alliances: The China Experience. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H.G.; Vermeulen, F. International Expansion through Start-up or Acquisition: A Learning Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, K.D.; Brouthers, L.E. Acquisition or Greenfield Start-up? Institutional, Cultural and Transaction Cost Influences. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delios, A.; Henisz, W.J. Japanese Firms’ Investment Strategies in Emerging Economies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramilli, M.K. Nationality and Subsidiary Ownership Patterns in Multinational Corporations. J. Int. Bus. 1996, 27, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erramilli, M.K.; Agarwal, S.; Kim, S. Are Firm-Specific Advantages Location-Specific Too? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 735–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennart, J.; Larimo, J. The Impact of Culture on the Strategy of Multinational Enterprises: Does National Origin Affect Ownership Decisions? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 515–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. Influences on Foreign Equity Ownership Level in Joint Ventures in China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J.; Delios, A. Location Specificity and the Transferability of Downstream Assets to Foreign Subsidiaries. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H.G.; Bell, J.H.J.; Pennings, J.M. Foreign Entry, Cultural Barriers, and Learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, W.C.; Thomas, H.; McGee, J. A Longitudinal Study of the Competitive Positions and Entry Paths of European Firms in the US Pharmaceutical Market. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, L.E.; Brouthers, K.D.; Werner, S. Is Dunning’s Eclectic Framework Descriptive or Normative? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busija, E.C.; O’Neil, H.M.; Zeithaml, C.P. Diversification Strategy, Entry Mode, and Performance: Evidence of Choice and Constraints. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.B. A Note on Countertrade: Contractual Uncertainty and Transaction Governance in Emerging Economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Parkhe, A. Importer Behavior: The Neglected Counterpart of International Exchange. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 495–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, S. Search and Deliberation in International Exchange: Microfoundations to Some Macro Patterns. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.I. Factors Affecting Export Intermediaries’ Service Offerings: The British Example. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Hill, C.W.; Wang, D.Y.L. Schumpeterian Dynamics vs. Williamsonian Considerations: A Test of Export Intermediary Performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Ilinitch, A.Y. Export Intermediary Firms: A Note on Export Development Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1998, 29, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, P.S.; Kotabe, M.; Teegen, H. Export Strategies and Performance of Firms from Emergingeconomies: Evidence from Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K. Domestic Competitive Position and Export Strategy of Japanese Manufacturing Firms: 1971–1985. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.B. Incidents of Gray Market Activity among US Exporters: Occurrences, Characteristics, and Consequences. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; New Impact Factors Announced Today for Publishing IB Related Papers. Res. Int. Bus. 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ibresearch/permalink/884747938685453/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

| Author | Articles | Author | Reviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saarenketo, S. | 44 | Alexander, N. | 5 |

| Kuivalainen, O. | 39 | McDougall, P.P. | 4 |

| Yemini, M. | 35 | Oviatt, B.M. | 4 |

| Dana, L.P. | 34 | Anwar, S.T. | 3 |

| Vissak, T. | 34 | Brand, U. | 3 |

| Buckley, P.J. | 33 | Cavusgil, S.T. | 3 |

| Crick, D. | 32 | Chan, G. | 3 |

| Johanson, J. | 32 | Etemad, H. | 3 |

| Etemad, H. | 31 | Finardi, K.R. | 3 |

| Alon, I. | 30 | Kumar, S. | 3 |

| Authors | Year | Cited by |

|---|---|---|

| Oviatt B.M. and McDougall P.P. [44] | 2005 | 1206 |

| Teece D.J. [45] | 2014 | 627 |

| Zahra S.A. [46] | 2005 | 585 |

| Cavusgil, S.T. and Knight G. [47] | 2015 | 497 |

| Delios, A. and Henisz, W.J. [48] | 2003 | 491 |

| Paul, J. & Parthasarathy, S. & Gupta, P. [49] | 2017 | 373 |

| Cazurra, A.C. & Inkpen, A. and Musacchio, A. and Ramaswamy, K. [50] | 2014 | 331 |

| Brannen, M.Y. [51] | 2004 | 331 |

| Autio, E. [52] | 2005 | 317 |

| Nummela, N., Saarenketo, S., Puumalainen, K. [53] | 2004 | 294 |

| Authors | Year | Cited by |

|---|---|---|

| Cavusgil S.T. and Knight G. [47] | 2015 | 497 |

| Paul J. & Parthasarathy S. and Gupta P. [49] | 2017 | 373 |

| Nummela N. & Saarenketo S. and Puumalainen K. [53] | 2004 | 294 |

| Wolff J.A. and Pett T.L. [54] | 2006 | 274 |

| Paul J. and Rosado-Serrano A. [28] | 2019 | 243 |

| Etemad H. [55] | 2004 | 201 |

| Bausch A. and Krist M. [56] | 2007 | 197 |

| Kocak A. and Abimbola T. [57] | 2009 | 125 |

| Luostarinen R. and Gabrielsson M. [58] | 2006 | 105 |

| Reuber, A.R. and Knight, G.A. and Liesch, P.W. and Zhou, L. [10] | 2018 | 104 |

| Authors | Year | Cited by |

|---|---|---|

| Chen, J. and Sousa, C.M.P. and He, X. [23] | 2016 | 164 |

| Brouthers, L.E. and Nakos, G. [59] | 2005 | 164 |

| Valos, M. and Baker, M. [60] | 1996 | 13 |

| Mysen, T. [61] | 2013 | 12 |

| Vaubourg, A.-G. [31] | 2016 | 9 |

| Din, M.U.D. and Ghani, E. and Mahmood, T. [62] | 2009 | 4 |

| Love J. [63] | 1982 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calheiros-Lobo, N.; Vasconcelos Ferreira, J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. SME Internationalization and Export Performance: A Systematic Review with Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118473

Calheiros-Lobo N, Vasconcelos Ferreira J, Au-Yong-Oliveira M. SME Internationalization and Export Performance: A Systematic Review with Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118473

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalheiros-Lobo, Nuno, José Vasconcelos Ferreira, and Manuel Au-Yong-Oliveira. 2023. "SME Internationalization and Export Performance: A Systematic Review with Bibliometric Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118473