Features of Nautical Tourism in Portugal—Projected Destination Image with a Sustainability Marketing Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To identify the legislation that supports nautical tourism in Portugal.

- To classify the actors that encompass nautical tourism in Portugal.

- To establish the projected image with an approach to the sustainable marketing of Portuguese nautical tourism.

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability in Nautical Tourism

2.2. Sustainable Marketing and Projected Destination Image

3. Methodology

3.1. Method, Data Collection, and Data Analysis Procedures

3.2. Research First Phase Procedures

3.3. Research Second Phase Procedures

3.4. Research Third-Phase Procedures

3.5. Research Model for Identifying the Projected Destination Image with a Sustainable Marketing Approach for Portuguese Nautical Tourism

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Features of the Portuguese Nautical Tourism

4.1.1. Nautical Legislation

4.1.2. Nautical Tourism Relevant Documents and Portuguese Government Programs

4.2. The Portuguese Nautical Stations: The Partners and Certification

4.2.1. The Portuguese Nautical Stations Features

4.2.2. Portuguese Nautical Stations Website Features

4.2.3. ENPs Projected Destination Image and Sustainable Marketing Approach

4.3. Support Structures for Portuguese Nautical Tourism

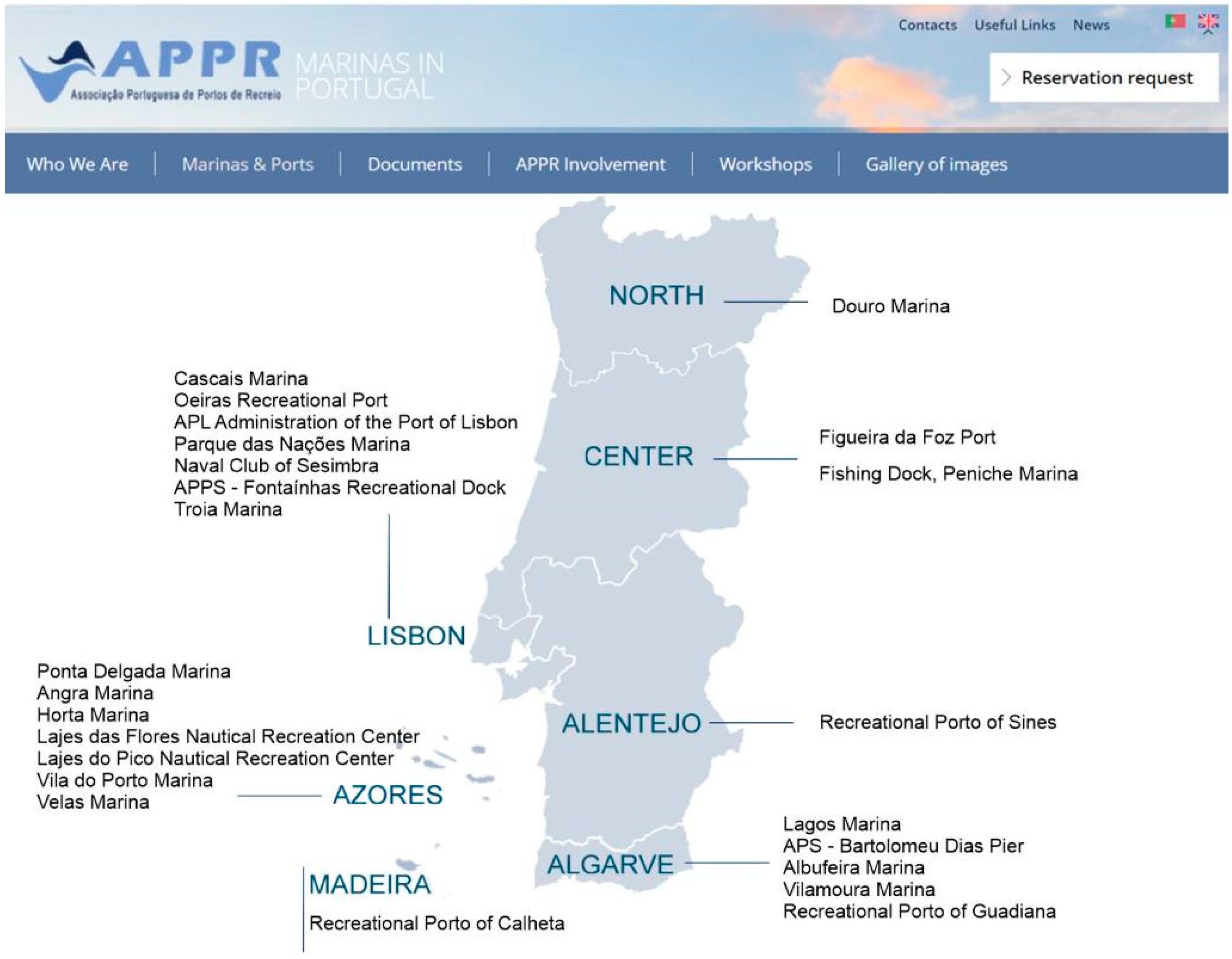

4.3.1. Marines and Recreational Ports

4.3.2. APPRs Marinas and Recreational Ports Projected Destination Image and Sustainable Marketing Approach

4.4. Portugal Cruises

4.4.1. Cruises Ports by Visit Portugal Webpage

4.4.2. Portuguese Cruises Ports Projected Destination Image and Sustainable Marketing Approach

5. Conclusions

5.1. The Actors That Encompass Nautical Tourism in Portugal-Governance

5.2. The Actors That Encompass Nautical Tourism in Portugal—Nautical Networks

5.3. The Actors That Encompass Nautical Tourism in Portugal—Mooring Boats

5.4. The Projected Destination Image with an Approach to Sustainable Marketing of Portuguese Nautical Tourism

5.5. Theoretical Implications

5.6. Practical Implications

5.7. Research Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. From the geography of tourism to geographies of tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Geographies; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pforr, C.; Dowling, R. Coastal tourism development: Planning and managing growth. In Coastal Tourism Development: Planning and Management Issues; Cognizant Communication Corporation: Elmsford, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro, M.B.; Mayer, V.F.; Luz, A.B.T. Nautical Sports Tourism: Improving People’s Wellbeing and Recovering Tourism Destinations. In Rebuilding and Restructuring the Tourism Industry: Infusion of Happiness and Quality of Life; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 130–156. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Vázquez, R.M.; Milán García, J.; De Pablo Valenciano, J. Analysis and trends of global research on nautical, maritime and marine tourism. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.J.; Otamendi, F.J. Fostering nautical tourism in the Balearic Islands. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C.; Spinelli, R. Evaluating the quality of web communication in nautical tourism: A suggested approach. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam-González, Y.; León González, C.; León Ledesma, J.D. Exploring preferences and perceptions of the European yachtsmen visiting the Canary Islands (Spain). Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 655–658. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, A.O. Cruise tourism. In Handbook of Tourism Economics: Analysis, New Applications and Case Studies; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013; pp. 339–359. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, S.F. La relevancia del turismo náutico en la oferta turística. Cuad. Tur. 2001, 7, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, T.; Dragin, A.; Armenski, T.; Pavic, D.; Davidovic, N. What demotivates the tourist? Constraining factors of nautical tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, H. Modalidades Turísticas: Características y Situación Actual; Universidad de La Habana: Havana, Cuba, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, R.C.; Rocha, A.; Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, C. Efficient delivery of forecasts to a nautical sports mobile application with semantic data services. In Proceedings of the Ninth International C* Conference on Computer Science Software Engineering, Porto, Portugal, 20–22 July 2016; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.A.; Assenov, I. The genesis of a new body of sport tourism literature: A systematic review of surf tourism research (1997–2011). J. Sport Tour. 2012, 17, 257–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.; Perna, F. Yachts passing by the west coast of Portugal–what to do to make the marina and the destination of Figueira da Foz a nautical tourism reference? Pomorstvo 2018, 32, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Visit Portugal. 2020. Available online: https://www.visitportugal.com/en (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Turismo de Portugal. Tourism Strategy 2027; Turismo de Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, M.; Silveira, L. Nautical Tourism in Croatia and in Portugal in the Late 2010’s: Issues and Perspectives. Pomorstvo 2018, 32, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, F.; Custódio, M.J.; Oliveira, V. Economia e Estratégia da Náutica como produto turístico no Crescimento Azul. In A Europa e o Mar: Inovação e Investigação Científica em Portugal; Centro de Documentação Europeia, Ed.; Universidade do Algarve, Centro de Documentação Europeia: Faro, Portugal, 2016; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, F.M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing. A Global Perspective; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gaviglio, A.; Bertocchi, M.; Marescotti, M.E.; Demartini, E.; Pirani, A. The social pillar of sustainability: A quantitative approach at the farm level. Agric. Food Econ. 2016, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, E.A. The history of sustainability the origins and effects of a popular concept. In Sustainability in Tourism: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, B.; Hall, C.M. Special Interest Tourism: In Search of an Alternative; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.M. O Turismo Náutico em Portugal: Caracterização e perspetivas de desenvolvimento. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, C.; Niza, S. The maritime cultural heritage as a resource for sustainable tourism: The case of the Ria Formosa (Portugal). J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sobral, M.P.; Lourenço, M.C. Tourism and heritage in Portuguese fishing communities: Learning from the past to build sustainable futures. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2192. [Google Scholar]

- Kortam, W.; Mahrous, A.A. Sustainable marketing: A marketing revolution or a research fad. Arch. Bus. Res. 2020, 8, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, E.; Mayer, M.; Sacher, P.; Ravanel, L. Visitors’ motivations to engage in glacier tourism in the European Alps: Comparison of six sites in France, Switzerland, and Austria. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 31, 1373–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecnik, M.; Gartner, W.C. Customer-based brand equity for a destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo, P.; Moreno-Gil, S. Analysis of the projected image of tourism destinations on photographs: A literature review to prepare for the future. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xiang, G.; Dong, Y. Network mechanism contrast: A new perspective of the ‘projection-perception’ contrast of the destination image. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 1482–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, A.; Groth, A. Projected and Perceived Destination Image of Tyrol on Instagram. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L.; Dias, F.; de Araújo, A.F.; Marques, M.I.A. A destination imagery processing model: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Alvarez, M.D.; Ertuna, B. Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. The myth of sustainable tourism. CSD Cent. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Niedziółka, I. Sustainable Tourism Development. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 8, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouganeli, S.; Trihas, N.; Antonaki, M.; Kladou, S. Aspects of sustainability in the destination branding process: A bottom-up approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Nepal, S.K. Sustainable tourism research: An analysis of papers published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.R.; Simões, J.; Simões, J.T.; Rosa, M.; Silva, J.; Santos, J.; Rego, C. Sustainable Management of Cultural and Nautical Tourism: Cultural and Tourist Enhancement Narrative (S). J. Tour. Herit. Res. 2022, 5, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Li, B. The Development of Marine Sports Tourism Based on Experience Economy. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 112, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabil, M.; Priatmoko, S.; Magda, R.; Dávid, L.D. Blue Economy and Coastal Tourism: A Comprehensive Visualization Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Y.E.L.; González, C.J.L.; de León Ledesma, J. Highlights of consumption and satisfaction in nautical tourism. A comparative study of visitors to the Canary Islands and Morocco. Gestión Ambiente 2015, 18, 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kasum, J.; Žanić Mikuličić, J.; Kolić, V. Safety issues, security and risk management in nautical tourism. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2018, 7, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, M. Social and Associative Sports Tourism in France: The Glénans and the National Union of Outdoor Sports Centres (UCPA). Int. J. Hist. Sport 2020, 37, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušić, E.; Šoda, J.; Krčum, M. The three-parameter classification model of seasonal fluctuations in the Croatian nautical port system. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.C.; Mascarenhas, M.V.; Flores, A.J.; Pires, G.M. Nautical small-scale sports events portfolio: A strategic leveraging approach. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. The development of marine sports tourism in the context of the experience economy. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 112, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Sun, Y. SWOT analysis of coastal sports tourism. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 112, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. Sustaining tourism, sustaining capitalism? The tourism industry’s role in global capitalist expansion. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 13, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.P.; Brandão, F.; Sousa, B. Towards socially sustainable tourism in cities: Local community perceptions and development guidelines. Enl. Tour. Pathmaking J. 2019, 9, 168–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.; Fernandes, M. Aquatic Event(S) in the Cultural and Nautical Diversity of a Destination. In Proceedings of the ICTR 2022 5th International Conference on Tourism Research, A Conference Hosted by Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 19–20 May 2022; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barke, M.; Towner, J. Learning from experience? Progress towards a sustainable future for tourism in the Central and Eastern Andalucian littoral. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, T. Nautical Tourism and Its Function in the Economic Development of Europe. In Visions for Global Tourism Industry; InTech Open: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhu, K.; Kang, L.; Dávid, L.D. Tea Culture Tourism Perception: A Study on the Harmony of Importance and Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Yan, X.; Alimov, A.; Farmanov, E.; Dávid, L.D. Regional sustainability: Pressures and responses of tourism economy and ecological environment in the Yangtze River basin. China Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.; Cardoso, L. How can brand equity for tourism destinations be used to preview tourists’ destination choice? An overview from the top of Tower of Babel. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2017, 13, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainability marketing research: Past, present and future. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 1186–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. A broad context model of destination development scenarios. Tour. Manag. 2000, 2, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, S.; McCabe, S.; Smith, A.P. The role of hedonism in ethical tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson-Fischer, U.; Liu, S. The impact of a global crisis on areas and topics of tourism research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Belz, F.M. Sustainability marketing—An innovative conception of marketing. Mark. Rev. St. Gallen 2010, 27, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugović, A.; Kovačić, M.; Hadžić, A. Sustainable development model for nautical tourism ports. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 17, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, J.C.; Cardoso, L.; Pereira, A.M.; Araújo-Vila, N.; de Almeida, G.G.F. Tourism ambassadors as special destination image inducers. Enl. Tour. Pathmaking J. 2021, 11, 194–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, I.; Marchiori, E. A comparison of pre-visit beliefs and projected visual images of destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.; Cardoso, L.; Araújo, N.; Dias, F. Understanding the role of destination imagery in mountain destination choice. Evidence from an exploratory research. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 22, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, D.; Shelley, D. Evaluation of websites using Balanced Scorecard (BSC) Approach in the Hotel Landscape in India. J. Tour. 2015, 16, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Camprubí, R.; Coromina, L. Content analysis in tourism research. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Steps in Conducting a Scholarly Mixed Methods Study; University of Nebraska: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pantano, E.; Servidio, R. An exploratory study of the role of pervasive environments for promotion of tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2011, 2, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Zhou, X.; Shen, C. Reconsidering Tourism Destination Images by Exploring Similarities between Travelogue Texts and Photographs. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2022, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chaoyang, F.; Hui, L. Characterizing Tourism Destination Image Using Photos’ Visual Content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2020, 9, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.C.; Woodside, A.G.; Miller, K. Analysing Iconic Consumer Brand Weblogs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Spring Symposium: Computational Approaches to Analyzing Weblogs, Stanford, CA, USA, 27–29 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kasum, J.; Vidan, P.; Baljak, K. Threats and New Protection Measures in Inland Navigation. PROMET. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2010, 22, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam-González, Y.E.; León, C.J.; Ledesma, J.L. Preferencias y valoración de los navegantes europeos en Canarias (España). Cuad. De Tur. 2017, 39, 311–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; MacInnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Understanding brands, branding and brand equity. Interact. Mark. 2003, 5, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Available online: https://www.ine.gov.ao/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Europe Union. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Marques, M.A.; Silva, J.A. The nautical stations program in Portugal: An analysis of its impact on coastal tourism development. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Guia Orientador do Turismo de Portugal. 2022. Available online: http://business.turismodeportugal.pt/SiteCollectionDocuments/ordenamento-turistico/guia-orientador-abordagem-ao-turismo-na-revisao-de-pdm-out-2021.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Gračan, D.; Agbaba, R. Analysis of crisis situations in nautical tourism. Pomorstvo 2021, 35, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.; Araújo Vila, N.; de Araujo, A.F.; Dias, F. Food tourism destinations’ imagery processing model. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1833–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Equity, M.B. Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 28, pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L.; Parameswaran, M.G.; Jacob, I. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. Relationship marketing in the era of network competition. Mark. Manag. 1994, 3, 18. [Google Scholar]

| Research Steps | Website | Link (accessed on 1 March 2023) | Research Focus, Needs, and Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Google search by keywords | https://www.visitportugal.com/pt-pt/experiencias/turismo-nautic https://www.nauticalportugal.com https://www.dgrm.mm.gov.pt/nautica-de-recreio | Activities in sea and river waters, weather, marinas, and what to visit. The need to define recreational marine leisure. The need to define nautical station. |

| 2nd | Portuguese government Laws–tourism | https://eportugal.gov.pt/ https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada | The need to define nautical tourism in Portuguese legislation. |

| 3rd | Infrastructures that support nautical tourism | http://www.marinasdeportugal.pt/pt/marinas-portos https://www.visitportugal.com | Access to Marinas and Ports. Access to Portugal Cruises information. |

| Legal Background | Application Area | Concepts Related to Nautical Tourism |

|---|---|---|

| Decree-Law no. 329/95, of 9 December. | Approves the regulation of recreational nautical tourism and establishes the type of boats. | Recreational nautical tourism |

| Decree-Law no. 478/99, of 9 November (Regulation approved by Decree no. 288/2000, of 25 May). | Approves the training and assessment process for recreational navigators, the issuing of the respective licenses, as well as the accreditation and supervision of training entities. | Recreational craft |

| Decree-Law no. 273/2000, of 9 November. | Approves the tariff regulations for the mainland port system. | Absent |

| Decree no. 689/2001, of 10 July. | Approves the rules for concluding civil liability insurance contracts for damages caused to third parties in the use of recreational boats. | Absent |

| Decree-Law no. 108/2009, of 15 May. | Establishes the conditions of access and exercise of the activity of tourist entertainment companies and sea-tourism operators of tourist entertainment activities. | Touristic recreation Maritime-tourism activities |

| Decree-Law no. 103/2010, of 24 September (Amended by Decree-Law no. 218/2015, of 7 October). | Environmental water quality, regulating river basins. It shall apply to (a) surface fresh waters, including all artificial water bodies and all heavily modified water bodies related thereto; (b) transitional waters; (c) coastal waters; (d) territorial waters. | Absent |

| Decree-Law no. 16/2014, of 3 February | Establishes the regime for the transfer of direct port jurisdiction of fishing ports and recreational marinas from the Instituto Portuário e dos Transportes Marítimos, I.P., to Docapesca-Portos e Lotas, S. A. | Absent |

| Decree-Law no. 149/2014, of 10 October. | Approves the regulation of vessels used in maritime-tourism activities (RVMT). | Maritime-tourism operators |

| Decree-Law no. 186/2015, of 10 October. | The republication originated a diploma that establishes the conditions of access and exercise of the activity of tourist entertainment companies and maritime-tourism operators, defining, among others, the need to register the company in the National Register of Tourist Entertainment Agents (RNAAT). The republication fits in with the National Nature Tourism Program, which includes outdoor activities/nature and adventure tourism. | Touristic recreation Maritime-tourism activities Tourism in nature Adventure tourism |

| Decree-Law no. 93/2018, of 13 November, amended by Decree-Law no. 84/2019, of 28 June, and Ministerial Order no. 242/2020, of 13 October. | Approves the new legal regime of recreational nautical tourism. | Recreational nautical tourism |

| Law no. 106/2019 of 6 September. | Establishes the regime of access and exercise of the activity of the sports coach. | Recreational craft |

| Nautical Station | Coordinating Entity | Logotype |

|---|---|---|

| Alijó Nautical Station | Municipality of Alijó |  |

| Alto Minho Nautical Station | Intermunicipal Community of Alto Minho |  |

| Aveiro Nautical Station | Aveiro City Council |  |

| Avis Nautical Station | Municipality of Avis |  |

| Baixo Guadiana Nautical Station | Guadiana Naval Association |  |

| Nautical Station of Cabeceiras de Basto | Municipality of Cabeceiras de Basto |  |

| Castelo do Bode Nautical Station | Intermunicipal Community of the Medio Tejo |  |

| Esposende Nautical Station | Municipality of Esposende |  |

| Estarreja Nautical Station | Municipality of Estarreja |  |

| Faro Nautical Station | Municipality of Faro |  |

| Moura-Alqueva Nautical Station | Municipality of Moura |  |

| Lagos Nautical Station | Municipality of Lagos |  |

| Macedo de Cavaleiros Nautical Station | Municipality of Macedo de Cavaleiros |  |

| Matosinhos Nautical Station | Municipality of Matosinhos | Absent |

| Monsaraz Nautical Station | Municipality of Reguengos de Monsaraz |  |

| Ílhavo Nautical Station | Municipality of Ílhavo |  |

| Murtosa Nautical Station | Municipality of Murtosa |  |

| Odemira Nautical Station | Municipality of Odemira |  |

| West Nautical Station | Intermunicipal Community of West |  |

| Ovar Nautical Station | Municipality of Ovar |  |

| Portimão Nautical Station | Municipality of Portimão |  |

| Póvoa de Varzim Nautical Station | Municipality of Póvoa do Varzim | Absent |

| Sesimbra Nautical Station | Municipality of Sesimbra |  |

| Sines Nautical Station | Municipality of Sines |  |

| Vagos Nautical Station | Municipality of Vagos |  |

| Vila do Conde Nautical Station | Municipality of Vila do Conde |  |

| Foz Côa Nautical Station | Municipality of Vila Nova de Foz Côa |  |

| Vila Verde Nautical Station | Municipality of Vila Verde |  |

| Vilamoura Nautical Station | Municipality of Vilamoura |  |

| Espinho Nautical Station | Municipality of Espinho |  |

| Alandroal Nautical Station | Municipality of Alandroal |  |

| Mértola Nautical Station | Municipality of Mértola |  |

| Marina/Recreational Port | Coordination | Website (accessed on 1 March 2023) | Logotype | Berths and Boat Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douro Marina | Absent | Site under maintenance |  | 300 berths 50 mt |

| Figueira da Foz Port | Private | https://portofigueiradafoz.pt |  | 360 berths 90mt |

| Fishing Dock, Peniche Marina | Public limited company | Absent |  | 140 berths 25 mt |

| Cascais Marina | Unidentified | https://marinacascais.com/ |  | 284 berths 25 mt |

| Oeiras Recreational Port | Unidentified | https://oeirasviva.pt/porto-de-recreio/ |  | 284 berths 25 mt |

| APL Administration of the Port of Lisbon | Private | https://www.portodelisboa.pt |  | 900 berths 1490 mt (4 recreational docks) |

| Parque das Nações Marina | Unidentified | https://marinaparquedasnacoes.pt |  | 600 berths 25 mt |

| Naval Club of Sesimbra | Unidentified | Absent |  | 207 berths 15 mt |

| APPS-Fontaínhas Recreational Dock | Unidentified | Linked with Ports Administration of Setubal | Absent | 178 berths 20 mt |

| Troia Marina | Private | Linked with Troia Resort Website https://www.troiaresort.pt |  | 100 berths 5.35 mt |

| Recreational Port of Sines | Unidentified | https://www.sinesmarina.com |  | 180 berths 25 mt |

| Lagos Marina | Unidentified | https://www.marinadelagos.pt |  | 462 berths 30 mt |

| APS-Bartolomeu Dias Pier | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Albufeira Marina | Absent | http://marina.marinaalbufeira.com/ |  | 470 berths 32 mt |

| Vilamoura Marina | Private | http://www.marinadevilamoura.com/pt |  | 825 berths 60 mt |

| Recreational Port of Guadiana | Absent | https://www.associacaonavaldoguadiana.pt/sobre |  | 360 berths 20 mt |

| Ponta Delgada Marina | Absent | https://portosdosacores.pt/marinas/marina-ponta-delgada |  | 640 berths 60 mt |

| Angra Marina | Absent | https://portosdosacores.pt/marinas/marina-ponta-delgada |  | 260 berths 25 mt |

| Horta Marina | Absent | www.portosdosacores.pt/marinas/marina-da-horta/ |  | 300 berths 15 mt |

| Lajes das Flores Nautical Recreation Center | Absent | www.portosdosacores.pt/marinas/nucleo-de-recreio-nautico-das-lajes-das-flores/ | Absent | 274 berths 25 mt |

| Lajes do Pico Nautical Recreation Center | Absent | www.portosdosacores.pt/marinas/nucleo-de-recreio-nautico-das-lajes-do-pico/ |  | 52 berths |

| Vila do Porto Marina | Absent | www.portosdosacores.pt/marinas/marina-vila-do-porto/ | Absent | 124 berths 12 mt |

| Velas Marina | Absent | www.portosdosacores.pt/marinas/nucleo-de-recreio-nautico-de-velas | Absent | 136 berths 15 mt |

| Recreational Port of Calheta | Absent | www.portorecreiocalheta.pt |  | 337 berths 25 mt |

| Ports Portugal Cruises | Coordination | Cruise Port Website (accessed on 1 March 2023) | Logotype | Docks and Boat Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leixões Port | Private | http://www.apdl.pt |  | 2 docks; 250 mt |

| Lisboa Port | Private | https://www.portodelisboa.pt |  | 4 docks; 20 mt |

| Portimão Port | Absent | https://www.apsinesalgarve.pt/porto-de-portimao/ |  | 1 dock; 215 mt |

| Ponta Delgada Port | Absent | https://portosdosacores.pt/portos/porto-de-ponta-delgada/ |  | 1 docks; 60 mt |

| Madeira Ports | Private | https://www.portosdamadeira.com/ |  | 4 docks; 260 mt |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardoso, L.; Lopes, E.; Almeida, G.G.F.d.; Lima Santos, L.; Sousa, B.; Simões, J.; Perna, F. Features of Nautical Tourism in Portugal—Projected Destination Image with a Sustainability Marketing Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118805

Cardoso L, Lopes E, Almeida GGFd, Lima Santos L, Sousa B, Simões J, Perna F. Features of Nautical Tourism in Portugal—Projected Destination Image with a Sustainability Marketing Approach. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118805

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardoso, Lucília, Eunice Lopes, Giovana Goretti Feijó de Almeida, Luís Lima Santos, Bruno Sousa, Jorge Simões, and Fernando Perna. 2023. "Features of Nautical Tourism in Portugal—Projected Destination Image with a Sustainability Marketing Approach" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8805. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118805

_Li.png)