1. Introduction

Global tourism is responsible for a significant carbon footprint (around 10%), contributing to environmental degradation and climate change [

1,

2]. Suppose there is no substantial change in current policies and business practices by 2050, then, if that is the case, the projected growth in tourism will consume 154% more energy and 152% more water, emit 131% more greenhouse gases and provide a 251% increase in solid waste [

3]. As a result, several organizations are calling for tourists to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) during their travels [

4,

5]. PEBs refer to actions individuals or groups take to promote the sustainability of natural resources and environmental protection [

6]. Habits of pro-sustainability are habits people adopt to live more sustainably. Therefore, PEBs are actions individuals take to reduce their negative environmental impacts [

7]. PEBs include using public transport, reducing energy and water consumption, and properly disposing of waste [

8]. The formation of PEBs is influenced by promoting certain factors, such as moral obligation, and inhibiting other factors, such as moral disengagement [

4,

9]. Sustainable information about a tourist destination is also important in forming PEBs. Sustainable information on tourist destinations refers to information that promotes sustainable tourism practices and helps visitors make responsible environmental choices during their travels [

10,

11].

Sustainable information about a tourist destination seeks to guide tourists on how to adopt sustainable practices during their trips to minimize the environmental and cultural impacts of tourism in regions [

10,

12]. This includes information on environmental activities, local conservation efforts and ways to reduce environmental impacts when travelling. For example, providing information about eco-friendly accommodations, local recycling programs, and sustainable transportation options can help tourists make more sustainable choices [

13]. By providing sustainable information about tourist destinations, tourists can make more informed decisions, helping to increase PEBs [

14].

In this context, tourists’ interest in sustainable tourism is growing. A Booking.com survey found that 72% of travelers believe people must make more sustainable choices to save the planet for future generations [

4]. Moreover, Aman, Hassan, Khattak, Moustafa, Fakhri and Ahmad [

8] showed that tourists’ PEBs could improve quality of life, reduce environmental footprints and contribute to sustainable development in tourism. Therefore, tourists must receive more sustainable information about tourist destinations to encourage PEBs. Unfortunately, tourism can negatively impact the environment in the form of pollution, habitat destruction and biodiversity loss [

13]. However, these negative impacts can be reduced by promoting sustainable information about tourist destinations and encouraging PEBs. What is the impact of promoting sustainable information about tourist destinations and the encouraging of pro-environmental behavior on reducing the negative impacts of tourism? Promoting sustainable information about tourist destinations can be an effective tool for encouraging PEBs among tourists. This is because such information provides evidence of the effectiveness of these behaviors and increases tourists’ abilities to adopt them [

4]. PEBs are key to ensuring the environmental sustainability of tourist destinations [

4]. Empirical research has shown that sustainable management of sites can be achieved by applying nudge techniques and norms and values theories [

14]. Moreover, tourists’ environmental awareness significantly improves quality of life, reduces environmental footprint and promotes PEBs [

8]. Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors in travel destinations exhibit social attributes of altruism and collective action [

7], reinforcing the importance of encouraging such behaviors. Therefore, providing sustainable information about tourist destinations can encourage tourists to act sustainably and reduce the negative environmental consequences of tourism activities [

4,

8]. High environmental awareness and knowledge can help tourists comply with sustainable development practices, while insufficient knowledge can lead to forgetfulness about environmental issues [

8].

Literature on PEBs in tourism highlights the importance of tourists’ PEBs in improving quality of life, reducing environmental footprint and promoting sustainable tourism [

8]. Zhang, et al. [

15] found that integrating a multi-level model, which considers national park management and individual behavior, can contribute to developing knowledge about PEBs. Meanwhile, Li and Wu [

16] highlighted that PEBs in tourist destinations exhibit social attributes of altruism and collective action. However, the literature still lacks studies that point to effective strategies to encourage tourists to have more sustainable practices during their trips, and more studies are needed considering different contexts [

17,

18]. Conducting new studies is important for several reasons. Firstly, sustainable tourism helps to protect the environment, natural resources and wildlife [

19]. Second, it provides socio-economic benefits for communities living in tourist destinations [

10]. Third, it conserves cultural heritage and creates authentic tourism experiences [

20]. Thus, more research is needed to explore how PEBs are promoted among tourists and how to measure their effectiveness in promoting sustainable tourism practices [

4,

13].

The literature also points to sustainable information on tourist destinations being essential to promote sustainable tourism practices [

21,

22]. Sustainability represents a key competitive advantage for tourist destinations, but most lack comprehensive information on sustainable practices [

17]. Recent research explores the use of ‘nudges’, environmental cues, that encourage desired behaviors, and normative theories of value beliefs, as potential approaches to facilitate sustainable destination management [

14,

23]. However, more research is needed to provide tourists with reliable and accurate information about sustainable tourism practices [

22,

24]. Therefore, it is important to make tourists aware of the environmental problems caused by tourism and provide them with sustainable information to encourage PEBs and to reduce negative impacts of tourism on the environment. How do sources of information on the sustainability of destinations cause changes in the behavior of tourists and induce pro-sustainable tourism and travel habits? How do pro-sustainable tourism and travel habits lead to changes in tourist behavior?

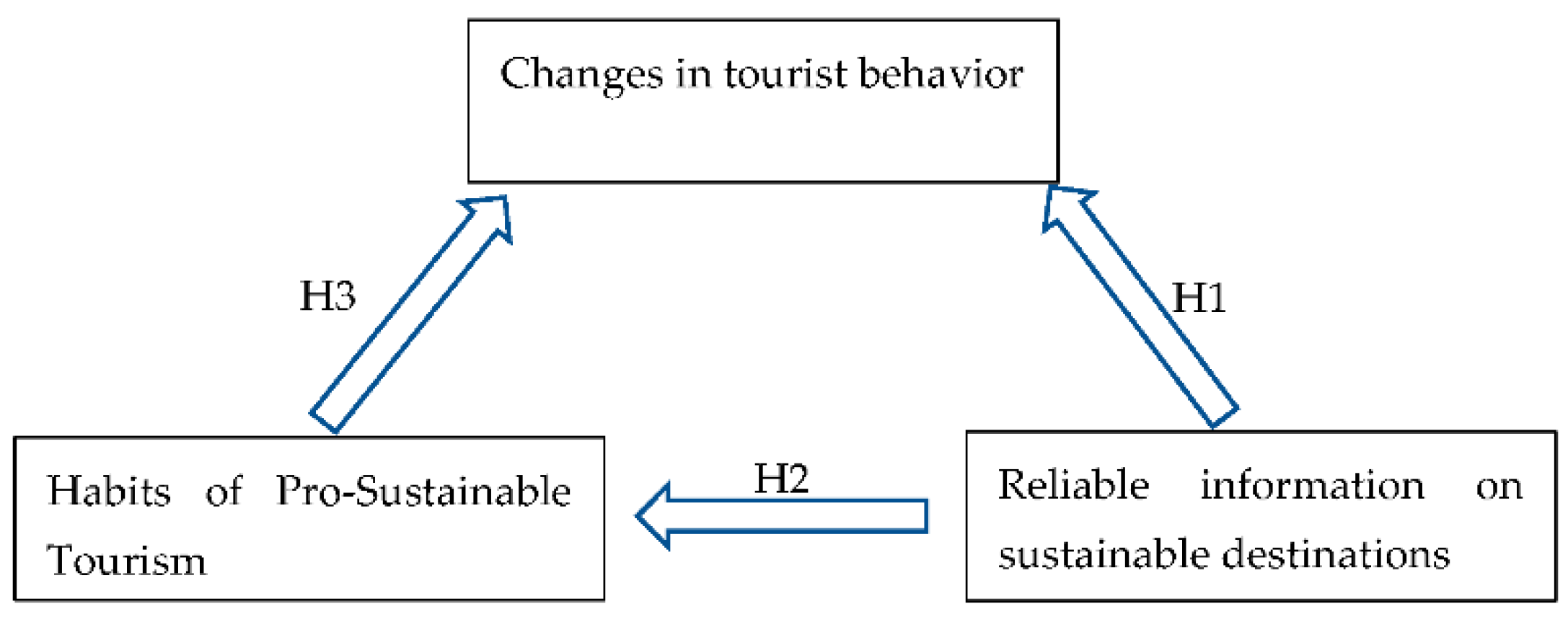

This research explores how reliable information about the sustainability of destinations can influence changes in travel and tourism behaviors and habits towards more environmentally friendly practices.

This paper presents three important contributions. Firstly, it highlights the fact that reliable information on the sustainability of tourist destinations positively promotes conscious and pro-sustainable travel behavior. With such information being accessible, tourists can be encouraged to make more responsible decisions regarding the destinations they choose to visit. Secondly, it emphasizes that the availability of accurate and accessible information on the sustainability of destinations can contribute to adopting pro-sustainable travel and tourism habits. Tourists with access to clear and reliable information are likelier to adopt more sustainable travel practices, such as waste reduction and resource conservation. Finally, it highlights that adopting pro-sustainable travel and tourism habits positively impacts the promotion of conscious and pro-sustainable travel behaviors. Tourists who already adopt these habits are more likely to continue to do so in the future and can positively influence others to do the same.

5. Discussion of Results

As the tourism industry continues to grow, it is critical to promote sustainable messages about tourist destinations and PEBs in the tourism industry. Thus, this paper fills several gaps in the literature by addressing the urgent need for sustainable tourism practices [

60] since tourism contributes significantly to the economies of many countries worldwide [

61]. However, it is important to highlight that most tourist destinations still lack comprehensive information on these practices [

17], despite the negative impact of tourism on the environment.

In the following, we discuss the relationship between reliable, sustainable information about tourist destinations and pro-environmental behaviors in tourism. The following discusses the relationship between reliable and sustainable information about tourist destinations and pro-environmental tourism behaviors.

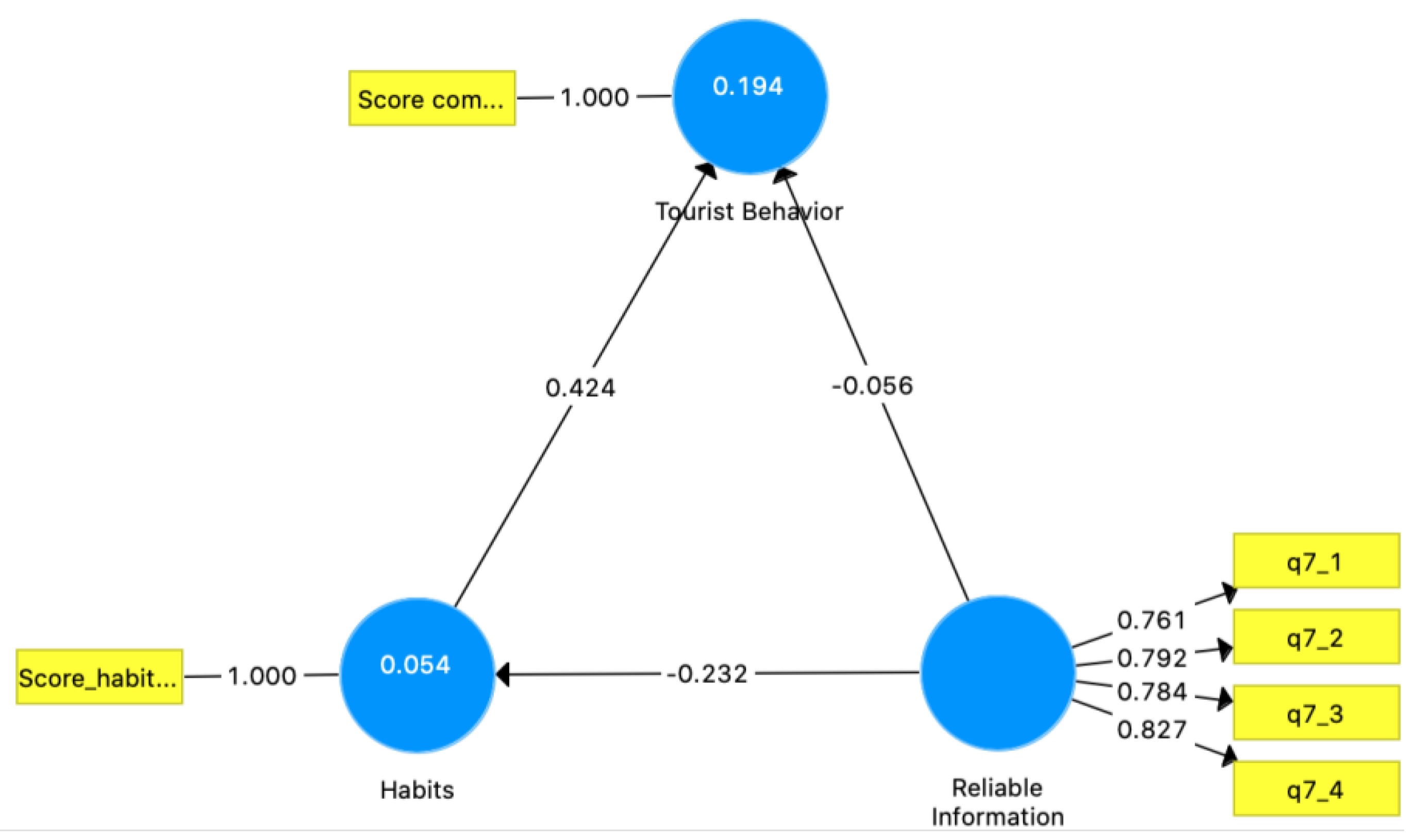

This study found that reliable information on the sustainability of destinations positively influences changes in tourist behavior, providing tourists with the information necessary to their developing concerns about environmental sustainability (H2). It was also confirmed that the available reliable information on the sustainability of destinations positively influences the adoption of pro-sustainable travel and tourism habits (H1). Therefore, tourists are likely to adopt pro-sustainable travel behavior when they have access to reliable information about the sustainable practices of destinations, which may influence their willingness to pay more if the sustainable practices of the destination contribute to improvement of the environment [

62]. This is based on the idea that awareness about sustainability can lead to behavioral changes, such as choosing more sustainable options during the trip. For example, if a tourist knows that a particular destination is committed to reducing its carbon footprint, they are likely to choose eco-friendly modes of transport.

Similarly, if tourists know that a particular destination is committed to reducing waste, they are likely to engage in sustainable waste management practices [

63]. However, for conscious decision-making, the tourist must have access to appropriate and accurate sustainable information, which is often not easily accessible because managers in the tourism sector have difficulty associating cost savings and increases in tourist demand to primarily sustainable projects [

64]. Furthermore, reliable information on tourist destinations can induce tourists to adopt pro-sustainable habits. These habits are a psychological reaction to the information about the tourist that can be promoted through the dissemination of information by technological means [

65].

In addition, concern for environmental sustainability is increasingly valued by tourists, leading to the appreciation of companies that adopt sustainable practices. These results are in line with those indicated by Tang, Ma and Ren [

9], Wang, et al. [

66] and Rais and Berrada [

67].

Finally, this study found that pro-sustainable travel and tourism habits positively influence pro-sustainable travel behavior (H3). This means that individuals already have pro-sustainable habits in their travel and tourism and more developed environmental and social awareness, making them more likely to adopt sustainable behavior in destination decisions. Thus, the tourist tends to choose destinations that adopt sustainable practices, opt for less polluting means of transport or reduce the consumption of natural resources during the trip. This result aligns with those of Xu, Huang and Whitmarsh [

6] and Tang, Ma and Ren [

9]. Studies have shown that when there are pro-sustainable habits on a day-to-day basis, translating, for example, into principles of sustainable consumption, the same habits tend to be extended during the holidays. Many of these pro-sustainable travel and tourism habits were [

22] adopted due to the pandemic, which made tourists more environmentally conscious, leading them to prefer inland destinations closer to nature [

68].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Conclusions

Compliance with the principles of environmental sustainability has been a challenge that tourist companies have tried to respond to in recent decades. However, over and above providing sustainable travel and tourism offers, the tourism industry needs to guide the transformation of tourist behavior according to the principles of environmental sustainability. Thus, the present study aimed to explore the role of available information on the sustainability of destinations in the pro-sustainable travel habits of tourists and the transformation of tourist behavior. It also aimed to explore the influence of tourists’ pro-sustainable travel habits on changes in travel and tourist behavior.

The results revealed that the available reliable information on the sustainability of destinations positively influences the adoption of pro-sustainable habits by tourists and transforms tourist behavior, providing it with principles of environmental sustainability. In addition, tourists with pro-sustainable habits regarding travel and tourism tend to adopt more environmentally sustainable behaviors when choosing tourist destinations.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to developing the literature on changes in tourist behavior, habits for pro-sustainable tourism and the availability of reliable information on sustainable destinations.

It was found that having access to credible information regarding the sustainability of travel destinations positively impacts pro-sustainable travel behavior, thus confirming H1. Credible information about the sustainability of a tourist destination is one of the most significant factors influencing pro-sustainable travel behavior. This, in turn, can affect tourists’ choice of travel destinations. Tourists tend to behave more pro-environmentally in destinations that have well-established and accessible sustainable initiatives, which suggests that the availability of reliable sustainability information can influence travel behavior [

55,

69]. Providing accurate and accessible information about sustainable destinations can encourage tourists to make more sustainable travel decisions, significantly contributing to preserving the environment and local communities. Therefore, information on sustainability must be available in a clear and easily accessible way so that tourists can make informed and responsible choices when planning their trips.

It was also found that having reliable information about the sustainability of tourist destinations positively impacts the adoption of pro-sustainable travel and tourism behaviors, thus confirming H2. Tourists with knowledge about the sustainability of their travel destinations are more inclined to adopt pro-sustainable behaviors, such as waste reduction and resource conservation [

70]. Therefore, providing reliable information about the sustainability of destinations can contribute to the adoption of pro-sustainable travel and tourism habits, which, in turn, can lead to a more sustainable and environmentally conscious tourism industry.

Finally, it was also found that adopting pro-sustainable travel and tourism practices positively promotes conscious and pro-sustainable travel behavior, thus confirming H3. Therefore, factors related to tourists’ attitudes and perceptions of a destination as being sustainable positively impacts tourist intentions to visit such eco-friendly places [

10,

71]. Promoting pro-sustainable travel and tourism practices can lead to an increase in the adoption of conscious and pro-sustainable behaviors during travel, thus contributing to the preservation of the environment and local communities [

72].

6.3. Practical Implications

This study infers a set of practical implications. First, the study demonstrates that the European population is changing its behavior towards travel and tourism, looking for sustainable tourist offers. Second, by meeting the demand for sustainable travel and tourism, companies in the tourism sector meet tourist demand and protect tourist destinations. In this way, those responsible for making tourist decisions about destinations must design strategies capable of promoting pro-sustainable behavior in tourists, adjusted to the characteristics of the destinations and to tourists with different profiles. Third, reliable information on tourist sustainability contributes positively to the adoption of sustainable travel and tourism habits and changes in tourist behaviors. In this way, tourist companies play a vital role in disseminating reliable information about the sustainability of tourist destinations to attract more tourists and preserve local resources. Adopting technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, social media and gamification via online media, can be good channels for communicating this information. Fourth, political decisions must focus on policies and regulations that encourage pro-sustainable habits in tourists, improving the population’s behavior while traveling and contributing to a more daily sustainable society. Fifth, education about pro-sustainable habits can transform the daily lives of people, helping to ensure that consumers, whether of essential goods or of tourist trips, are guided by sustainability principles.

6.4. Limitations and Future Lines of Investigation

This study is not without limitations. The sample was collected through a secondary database, and, as such, the indicators used in this study were based on available data. The constructs used with different indicators could lead to different results, ideal for additional primary data collection for greater significance of the study. In addition, the database included responses from participants from several countries, and, in future studies, nationalities may be considered a moderate variable. Pro-sustainable habits and reliable information available on the sustainability of destinations only explain tourists’ pro-sustainable behavior. In future studies, the personality traits of tourists, such as the big five, should also be considered. In addition, pro-sustainable habits were measured by indicators directly related to practices carried out by tourists during vacation trips. It would be interesting to assess how tourists adopt pro-sustainable habits in their homes and relate to habits when traveling. The database of this study considers a large sample of European participants without regard to socio-demographic characteristics. Thus, in future lines of investigation, gender, age, and education could be considered moderate variables of the research model to assess whether the results obtained would be different. Comparative studies between European countries are also suggested to explore the cultural role in tourists’ habits and pro-sustainable behaviors. The variable information available on sustainable destinations does not consider communication channels. It would be essential to assess whether different types of information channels are important antecedents of tourists’ absorption of sustainable information about destinations.