Student’s Co-Creation Behavior in a Business and Economic Bachelor’s Degree in Italy: Influence of Perceived Service Quality, Institutional Image, and Loyalty

Abstract

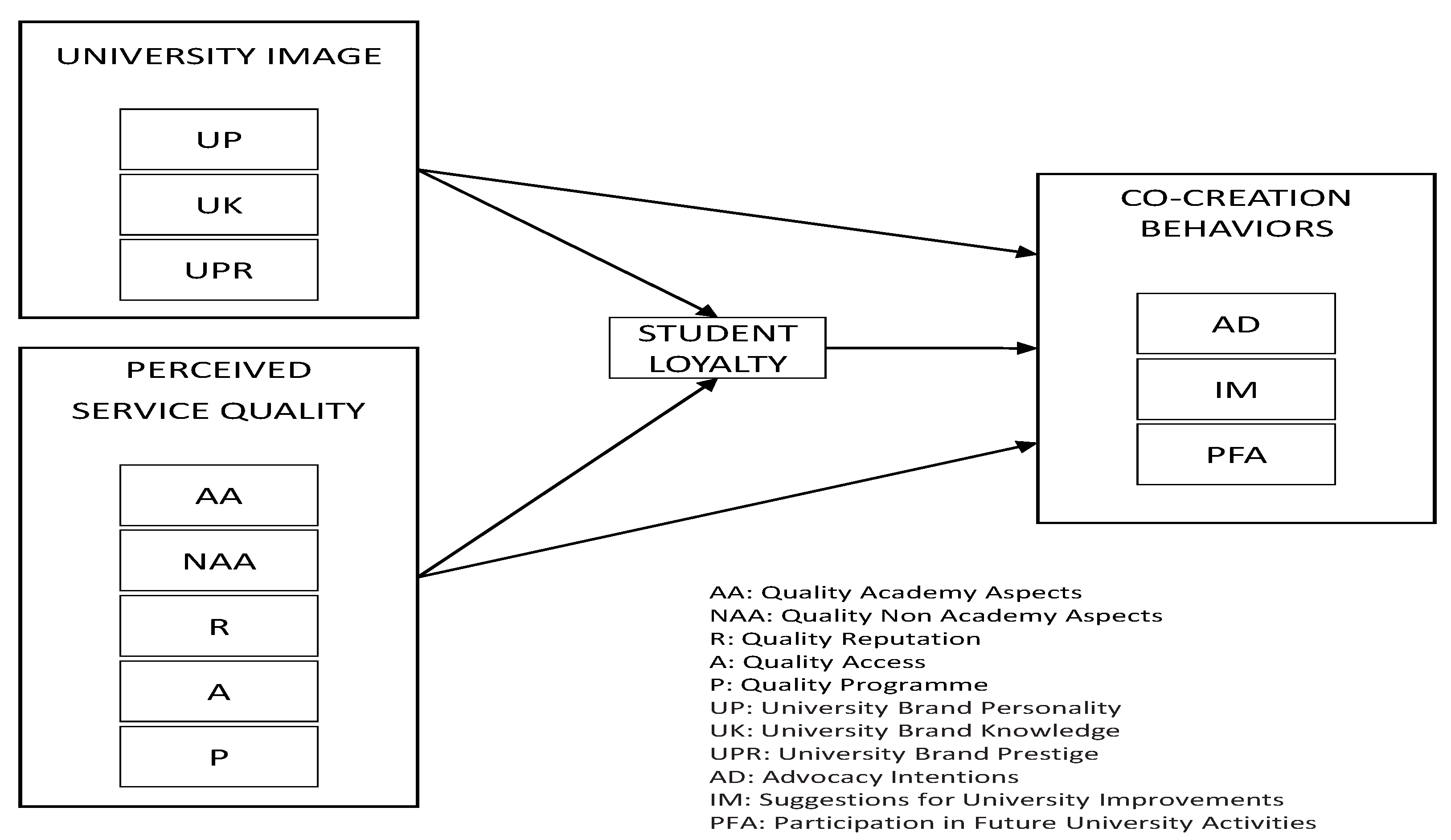

1. Introduction

1.1. Students’ Co-Creation Behaviors in Higher Educational Context

1.2. Students’ Loyalty

1.3. Perceived Service Quality

1.4. Institutional Image

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study 1 (Questionnaire)

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measures

Perceived Service Quality

University Brand Image

Students’ Loyalty

Co-Creation Behaviors

2.1.3. Data Analysis

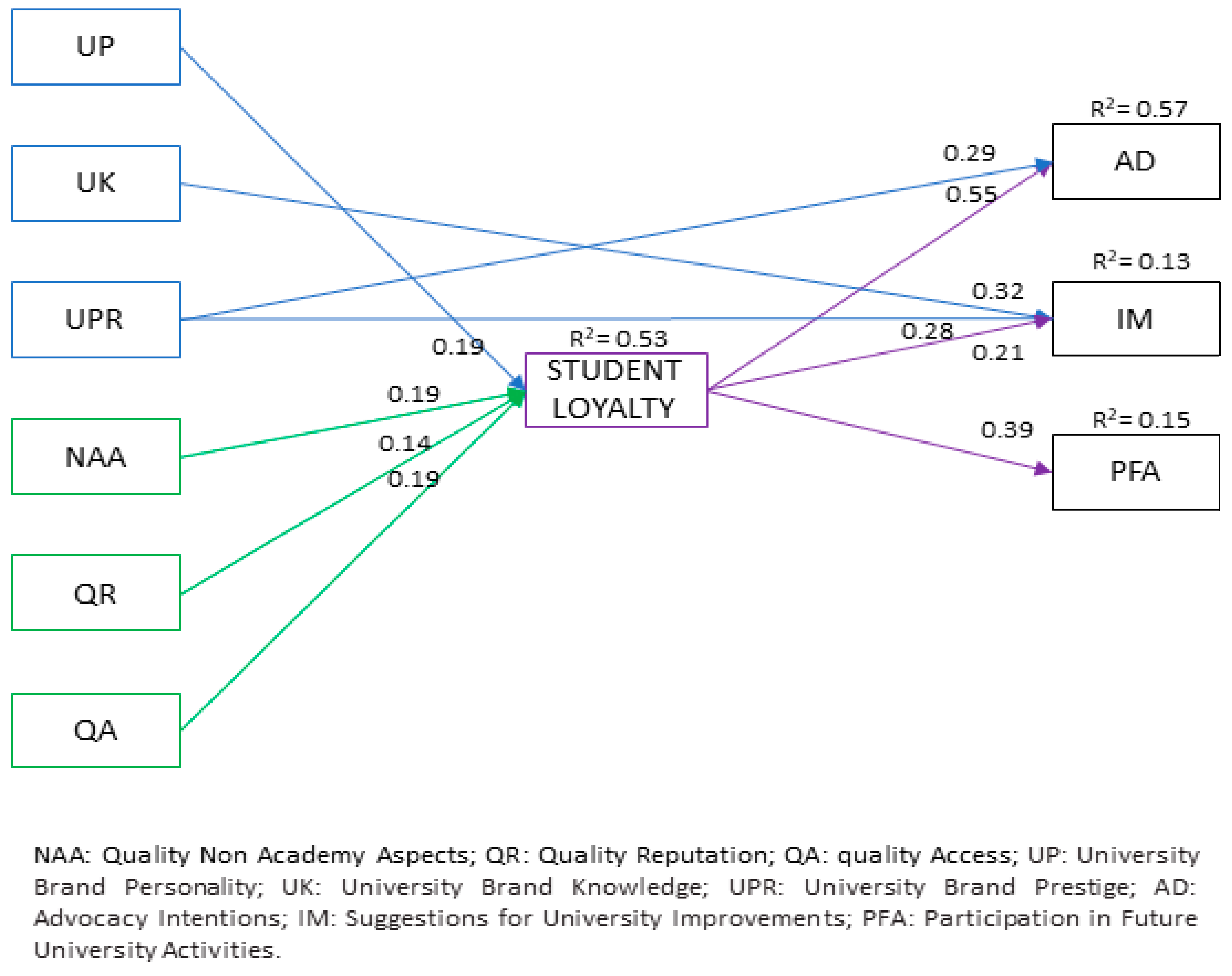

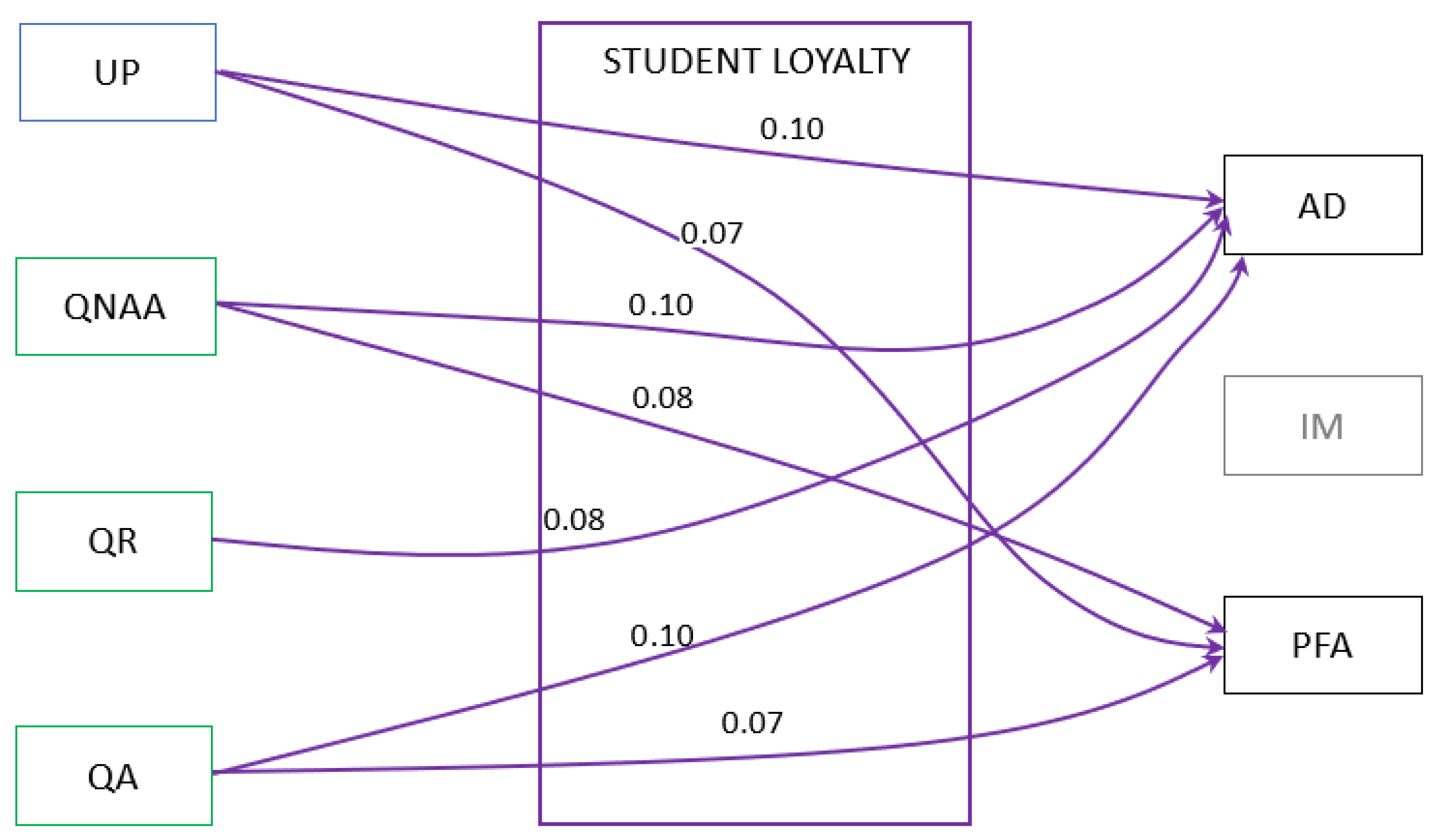

2.1.4. Findings

2.2. Study 2 (Focus Groups)

2.2.1. Results

Dialogue and Trust

“We students aren’t account to improve the university quality”.

“For the decision-makers, the students have not skills and information appropriate to give suggestions. Their opinion has been taken as such, as an opinion”.

“At the moment, our HEI provides for the administration by all students of the teaching evaluation forms. The problem is that the students don’t know how much their suggestions and criticism are considered for quality improvement. Students have an interest in adopting active and participatory roles that allow them to interact and work collaboratively with teachers and institutions”.

“The collaboration needs the availability by the university to share information, resources, decisions, and to operate transparently so as to make students understand that there is an interest in building a relationship based on mutual trust”.

“In my opinion, trust is the most important driver in developing a strong relationship between students and university”.

Quality of Academic and Non-Academic Aspects

“I would recommend it because the professors are capable, and the programs are interesting. Moreover, my university is one of the largest institutions in the region of Sardinia due to its international policy and studies, and its agreements with prestigious universities in Europe and the world“.

“A very positive aspect is the variety of teachings in the degree program. There are excellent student facilities including halls of residence, libraries, sports facilities, and museum”.

“University taxes are determined based on profit and income”.

“The courtesy of the university staff was an important element for me. The university staff provided all the information to improve the university experience”.

“I’m proud to be part of my university because it offers a unique and memorable student experience. By engaging in continuous activities, we can interact and collaborate with the university and thus enhance the university’s brand image. Students’ participation in the extra-curricular activities demonstrates their brand commitment”.

Image and Reputation

“I have a positive image of my university because, in recent years, Universality’s public engagement policies have increased enormously. My department is committed to communicating and spreading knowledge through direct relationships with territory and stakeholders”.

“Differents are the initiative organized by my university, such as public events (inauguration ceremony of the academic year, researchers’ night), concerts, health safety initiatives, urban development, and enhancement of the territory”.

“I’m very proud of my university because it has a century-old history. It was founded in the 1620s by Filippo III of Spain. Today it is in the top 600 universities of the world”.

“My decision to enroll in my university is influenced by its positive brand image. In the last years, the website of the university emphasized its competencies. For example, the institution strongly communicates the competence of its research staff and the achievement of international results”.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raza, H.; Ali, A.; Rafiq, N.; Xing, L.; Asif, T.; Jing, C. Comparison of Higher Education in Pakistan and China: A Sustainable Development in Student’s Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X. The Influence of Social Capital and Intergenerational Mobility on University Students’ Sustainable Development in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masserini, L.; Bini, M.; Pratesi, M. Do Quality of Services and Institutional Image Impact Students’ Satisfaction and Loyalty in Higher Education? Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 146, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faham, E.; Rezvanfar, A.; Mohammadi, S.H.M.; Nohooji, M.R. Using System Dynamics to Develop Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education with the Emphasis on the Sustainability Competencies of Students. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 123, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Asaad, Y.; Yen, D.A.; Gupta, S. IMO and Internal Branding Outcomes: An Employee Perspective in UK HE. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation Experiences: The Next Practice in Value Creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Service Logic Revisited: Who Creates Value? And Who Co-creates? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2008, 20, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the Co-creation of Value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Gouillart, F.J. The Power of Co-Creation: Build It with Them to Boost Growth, Productivity, and Profits; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1439181041. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L.; O’brien, M. Competing through Service: Insights from Service-Dominant Logic. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Pervan, S.J.; Beatty, S.E.; Shiu, E. Service Worker Role in Encouraging Customer Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer Value Co-Creation Behavior: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. Customers as Good Soldiers: Examining Citizenship Behaviors in Internet Service Delivers. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Yu, Q.; Gupta, S.; Foroudi, M.M. Enhancing University Brand Image and Reputation through Customer Value Co-Creation Behaviour. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 138, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, M.; Lodge, J.; Coates, H. Co-Creation in Higher Education: Towards a Conceptual Model. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2018, 28, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemi, T.; Krogh, L. Co-Creation in Higher Education: Students and Educators Preparing Creatively and Collaboratively to the Challenge of the Future; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, M.; Lodge, J. Student-Staff Co-Creation in Higher Education: An Evidence-Informed Model to Support Future Design and Implementation. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharnouby, T.H. Student co-creation behavior in higher education: The role of satisfaction with the university experience. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2015, 25, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.G. Customer citizenship behavior: An expanded theoretical understanding. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bove, L.; Robertson, N.; Pervan, S. Customer citizenship behaviours: Towards the development of a typology. In ANZMAC 2003: A Celebrations of Ehrenberg and Bass: Marketing Discoveries, Knowledge and Contribution, Conference Proceedings; University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2003; pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. A review of customer citizenship behaviors in the service context. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Huisman, J. Student evaluation of university image attractiveness and its impact on student attachment to international branch campuses. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2013, 17, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.; Jagun, A. Customer care, customer satisfaction, value, loyalty and complaining behavior: Validation in a UK university setting. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 1997, 1, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, N. Elevating Student Voice: How to Enhance Student Participation, Citizenship and Leadership; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.S.; Roy, S.K.; Sadeque, S. Antecedents and consequences of university brand identification. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3023–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athiyaman, A. Linking student satisfaction and service quality perceptions: The case of university education. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, Ø.; Nesset, E. What accounts for students’ loyalty? Some field study evidence. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2007, 21, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.; Awang, Z. Building corporate image and securing student loyalty in the Malaysian higher learning industry. J. Int. Manag. Stud. 2009, 4, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S. What drives student loyalty in universities: An empirical model from India. Int. Bus. Res. 2011, 4, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunanusorn, A.; Puttawong, D. The Mediating Effect of Satisfaction on Student Loyalty to Higher Education Institution. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianden, J.; Barlow, P.J. Showing the Love: Predictors of Student Loyalty to Undergraduate Institutions. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2014, 51, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Langer, M.F.; Hansen, U. Modeling and Managing Student Loyalty: An Approach Based on the Concept of Relationship Quality. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, G.R.; Rillo, A.P. Structural Equation Modeling of Co-Creation and Its Influence on the Student’s Satisfaction and Loyalty towards University. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2016, 291, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.; Cervera, A.; Pérez-Cabañero, C. Sticking with Your University: The Importance of Satisfaction, Trust, Image, and Shared Values. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 2178–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, T.; Ng, M.; Chandra, S.; Priyono, P. The Effect of Service Quality on Student Satisfaction and Student Loyalty: An Empirical Study. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2018, 9, 109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Borishade, T.T.; Ogunnaike, O.O.; Salau, O.; Motilewa, B.D.; Dirisu, J.I. Assessing the Relationship among Service Quality, Student Satisfaction and Loyalty: The Nigerian Higher Education Experience. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Olson, D.L.; Trimi, S. Co-innovation: Convergenomics, Collaboration, and Co-creation for Organizational Values. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyono, H.; Hadian, A.; Purba, N.; Pramono, R. Effect of Service Quality toward Student Satisfaction and Loyalty in Higher Education. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.V.T.; Nguyen, Q.A.T.; Phan, M.H.T.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, H.T. Vietnamese Students’ Satisfaction toward Higher Education Service: The Relationship between Education Service Quality and Educational Outcomes. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 1397–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alfy, S.; Abukari, A. Revisiting Perceived Service Quality in Higher Education: Uncovering Service Quality Dimensions for Postgraduate Students. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2020, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamdevula, S.; Bellamkonda, R.S. Effect of Student Perceived Service Quality on Student Satisfaction, Loyalty and Motivation in Indian Universities: Development of HiEduQual. J. Model. Manag. 2016, 11, 488–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.S.; de Moraes, G.H.S.M.; Makiya, I.K.; Cesar, F.I.G. Measurement of Perceived Service Quality in Higher Education Institutions: A Review of HEdPERF Scale Use. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2017, 25, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Argüelles, M.J.; Batalla-Busquets, J.M. Perceived Service Quality and Student Loyalty in an Online University. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2016, 17, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, Q. The Influence of Academic Self-Efficacy on University Students’ Academic Performance: The Mediating Effect of Academic Engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F. HEdPERF versus SERVPERF: The Quest for Ideal Measuring Instrument of Service Quality in Higher Education Sector. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2005, 13, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F. Measuring Service Quality in Higher Education: HEdPERF versus SERVPERF. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2006, 24, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Vasquez-Parraga, A.Z.; Kara, A.L.I.; Cerda-Urrutia, A. Determinants of Student Loyalty in Higher Education: A Tested Relationship Approach in Latin America. Lat. Am. Bus. Rev. 2009, 10, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamdevula, S.; Bellamkonda, R.S. The Effects of Service Quality on Student Loyalty: The Mediating Role of Student Satisfaction. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 11, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembiring, M.G. Determinants of Students’ Loyalty at Universitas Terbuka. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 2013, 8, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinder, K.; Datta, B. A Study of the Effect of Perceived Lecture Quality on Post-Lecture Intentions. Work Study 2003, 52, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randheer, K. Service Quality Performance Scale in Higher Education: Culture as a New Dimension. Int. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziconstantis, C.; Kolympari, T. Student Perceptions of Academic Service Learning: Using Mixed Content Analysis to Examine the Effectiveness of the International Baccalaureate Creativity, Action, Service Programme. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2016, 15, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiewanto, A.; Laurens, C.; Nelloh, L. Influence of Service Quality, University Image, and Student Satisfaction toward WOM Intention: A Case Study on Universitas Pelita Harapan Surabaya. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwiya, B.; Bwalya, J.; Siachinji, B.; Sikombe, S.; Chanda, H.; Chawala, M. Higher Education Quality and Student Satisfaction Nexus: Evidence from Zambia. Creat. Educ. 2017, 8, 1044–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.; Yang, S.U. Toward the Model of University Image: The Influence of Brand Personality, External Prestige, and Reputation. J. Public Relat. Res. 2008, 20, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarus, D.K.; Rabach, N. Determinants of Customer Loyalty in Kenya: Does Corporate Image Play a Moderating Role? TQM J. 2013, 25, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Raposo, M. The Influence of University Image on Student Behaviour. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2010, 24, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.M.; Mazzarol, T.W. The Importance of Institutional Image to Student Satisfaction and Loyalty within Higher Education. High. Educ. 2009, 58, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, E.M. The Relationship between the University Image and Students’ Willingness to Recommend It. Cross-Cult. Manag. 2016, 18, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Shamsudin, M.F.; Mustapha, I. The Effect of Service Quality and Corporate Image on Student Satisfaction and Loyalty in TVET Higher Learning Institutes (HLIs). J. Tech. Educ. Train. 2019, 11, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barich, H.; Kotler, P. A Framework for Marketing Image Management. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Andreasen, A.R. Strategic Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996; ISBN 9780132345545. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, U.; Sahin, O. A Literary Excavation of University Brand Image Past to Present. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Choudhury, R.; Bennett, R.; Savani, S. University Marketing Directors’ Views on the Components of a University Brand. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2009, 6, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, S.F.S.; Kitchen, P.J. Projecting Corporate Brand Image and Behavioral Response in Business Schools: Cognitive or Affective Brand Attributes? J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2324–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Raposo, M. Conceptual Model of Student Satisfaction in Higher Education. Total Qual. Manag. 2007, 18, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, J. The Pitfalls and Promise of Focus Groups as a Data Collection Method. Sociol. Methods Res. 2016, 45, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Jaspersen, L.J.; Thorpe, R.; Valizade, D. Management and Business Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A. Developing Questions for Focus Groups; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarth, C.; Schmidt, M. How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of ‘internal brand equity’in a business-to-business setting. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS, Structural Equations, Program Manual, Program Version 3.0; BMDP Statistical Software: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative Fit Indices in Structural Models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.P.; Ferreira, J.J. Service quality, loyalty, and co-creation behaviour: A customer perspective. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2022, 14, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL: Reconciling performance-based and perceptions-minus-expectations measurement of service quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Huisman, J. The components of student–university identification and their impacts on the behavioural intentions of prospective students. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2013, 35, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes-Giner, G.; Perello-Marín, M.R.; Dıaz, O.P. Co-creation in Undergraduate Engineering Programs: Effects of Communication and Student Participation. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrøm, A.; Ghinea, G. Co-creation of value in higher education: Using social network marketing in the recruitment of students. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2013, 35, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes-Giner, G.; Perello-Marín, M.R.; Díaz, O.P. Co-creation impacts on student behavior. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 228, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Méndez, M.; Gummesson, E. Value co-creation and university teaching quality: Consequences for the European higher education area (EHEA). J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Lazarus, D.; Dhaka, S. Co-creation channel: A concept for paradigm shift in value creation. J. Manag. Sci. Pract. 2013, 1, 14. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Definition | No Items | Example of Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-academic aspects | Quality service does not include the academic aspect, but can significantly depend on the provision of non-academic support of the service delivery. This dimension contains variables such as adequate space in the university building for the number of students enrolled; a nondiscrimination policy followed by all faculty and staff members; provision of extra-curricular activities; friendliness of the administrative staff; and recreational facilities. | 12 | The institution’s staff provides individual attention. |

| Academic aspect | This dimension refers to the duties and responsibilities of the academics. The main duty of academic staff is to transmit knowledge through research; provide more attention to students’ needs; sufficient resources to assist with teaching and learning; and the feedback that teachers give to students about their progress. | 9 | The teaching staff is highly qualified and experienced in its respective field or knowledge. |

| Reputation | This dimension denotes the image of the institution perceived by the students compared to others in the area. | 9 | The institution location is ideal, and the layout and appearance of campuses are excellent. |

| Access | This dimension is related to the easy of contact, approachability, and availability of items. | 7 | The institution has a standardized and simple procedure for providing services. |

| Program issue | The dimension program issue concentrates on the importance of specialization offered by the HEI. | 2 | The institution provides programs with flexible structures and study plans. |

| Dimensions | Definitions | No Items | Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| University personality (UP) | It is the set of human characteristics associated with the university, which are developed based on students’ direct or indirect experiences with the university. | 4 | This university is: friendly, stable, practical, and warm. |

| University knowledge (UK) | It is the students’ perception of how the knowledgeable he or she has about the communications, values, and benefits associated with the university. | 4 | I am aware of the [university] goals. I have sound knowledge about the values represented by the [university]. I understand how students can benefit from the [university]. I know how [university] differentiates us from the competitors. |

| University external prestige | External prestige is commonly viewed as an individual-level variable since it is based on individual perceptions of an organization’s prestige, which may vary depending on the individual’s exposure to information about the organization. | 3 | The [university] maintains a high standard of academic excellence. It is considered prestigious to be an alumnus of the [university]. [University] has a rich history. |

| Definition | No Items | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ loyalty | Student loyalty refers to the loyalty of a student during and after his or her time at the university. | 6 | I would recommend my course to someone else. I would recommend my university to someone else. I am very interested in keeping in touch with “my faculty”. If I was faced with the same choice again, I would still choose the same course. If I was faced with the same choice again, I would still choose the same university. I would become a member of any alumni organizations at my old university or faculty. |

| Dimensions | No Items | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Suggestions for university improvement | 4 | I would make suggestions to [university] as to how it can be improved. I would let the [university] know of ways that could make it better serve my needs. I would share my opinions with my [university] if I felt they might be of benefit. I would contribute ideas to my [university] that could help it improve service. |

| Advocacy intention | 4 | I will recommend [university] to others. I will recommend [university] to those who ask or seek my advice. I will recommend others on the [university] social media (e.g., Facebook or Twitter). I will post positive comments about the [university] on my social media (e.g., Facebook). |

| Participation in future university activities | 2 | I would attend future events being sponsored by my [university]. I would attend future functions held by my [university]. |

| Dimensions | Mean | St.Dev. | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| University Brand Personality | 2.80 | 0.78 | 0.74 |

| University Brand Knowledge | 2.62 | 0.84 | 0.73 |

| University Brand Prestige | 2.84 | 0.82 | 0.76 |

| Advocacy Intentions | 2.93 | 0.98 | 0.83 |

| Suggestions for University Improvements | 2.30 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| Participation in Future University Activities | 2.44 | 0.99 | 0.84 |

| Student Loyalty | 2.60 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| HedPERF Academy Aspects | 2.70 | 0.71 | 0.86 |

| HedPERF Non Academy Aspects | 2.94 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| HedPERF Reputation | 3.02 | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| HedPERF Access | 2.57 | 0.62 | 0.76 |

| HedPERF Programme | 2.85 | 0.86 | 0.71 |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | ||

| 1. | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2. | University Brand Personality | 0.48 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. | University Brand Knowledge | 0.51 *** | 0.40 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. | University Brand Prestige | 0.55 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.62 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 5. | Advocacy Intentions | 0.03 | 0.20 *** | −0.08 | 0.06 | 1 | ||||||

| 6. | Suggestions for University Improvements | 0.33 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.26 *** | 1 | |||||

| 7. | Participation in Future University Activities | 0.55 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.72 *** | 0.14 * | 0.39 *** | 1 | ||||

| 8. | Student Loyalty | 0.45 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.08 | 0.29 *** | 0.51 *** | 1 | |||

| 9. | HedPERF Academy Aspects | 0.41 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.03 | 0.27 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.60 *** | 1 | ||

| 10. | HedPERF Non Academy Aspects | 0.52 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.05 | 0.20 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.47 *** | 1 | |

| 11. | HedPERF Reputation | 0.41 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.19 ** | 0.27 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.54 *** | 1 |

| 12. | HedPERF Access | 0.35 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.01 | 0.16 * | 0.38 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.43 *** |

| Fit Index | χ2 (df) | p | CFI | RMSEA | NFI | NNFI | GFI | AGFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 104.48 (37) | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

| Variables | β | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| UP → AD | 0.10 | 9.71 | <0.01 |

| UP → IM | ns | ||

| UP → PFA | 0.07 | 4.30 | <0.01 |

| QNAA → AD | 0.10 | 6.96 | <0.01 |

| QNAA → IM | ns | ||

| QNAA → PFA | 0.07 | 4.50 | <0.01 |

| QR → AD | 0.08 | 6.91 | <0.01 |

| QR → IM | ns | ||

| QR → PFA | ns | ||

| QA → AD | 0.10 | 6.46 | <0.01 |

| QA → IM | ns | ||

| QA → PFA | 0.07 | 3.85 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinna, R.; Cicotto, G.; Jafarkarimi, H. Student’s Co-Creation Behavior in a Business and Economic Bachelor’s Degree in Italy: Influence of Perceived Service Quality, Institutional Image, and Loyalty. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118920

Pinna R, Cicotto G, Jafarkarimi H. Student’s Co-Creation Behavior in a Business and Economic Bachelor’s Degree in Italy: Influence of Perceived Service Quality, Institutional Image, and Loyalty. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118920

Chicago/Turabian StylePinna, Roberta, Gianfranco Cicotto, and Hosein Jafarkarimi. 2023. "Student’s Co-Creation Behavior in a Business and Economic Bachelor’s Degree in Italy: Influence of Perceived Service Quality, Institutional Image, and Loyalty" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118920

APA StylePinna, R., Cicotto, G., & Jafarkarimi, H. (2023). Student’s Co-Creation Behavior in a Business and Economic Bachelor’s Degree in Italy: Influence of Perceived Service Quality, Institutional Image, and Loyalty. Sustainability, 15(11), 8920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118920