Bridging the Great Divide: Investigating the Potent Synergy between Leadership, Zhong-Yong Philosophy, and Green Innovation in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Zhong-Yong Thinking: Entrepreneurial/Leadership Prospects

2.2. Green Innovation

2.3. Zhong-Yong Thinking and Green Innovation

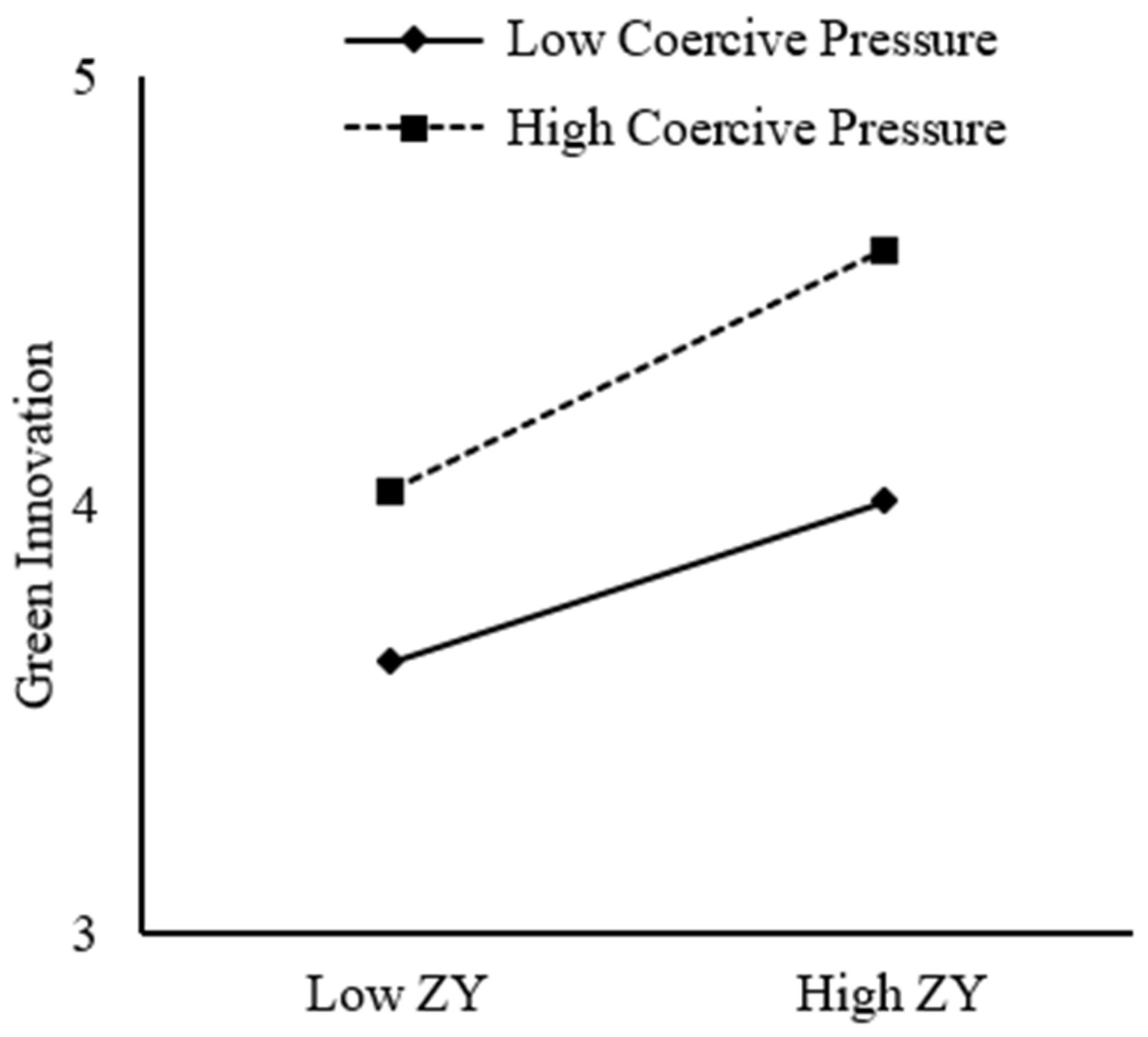

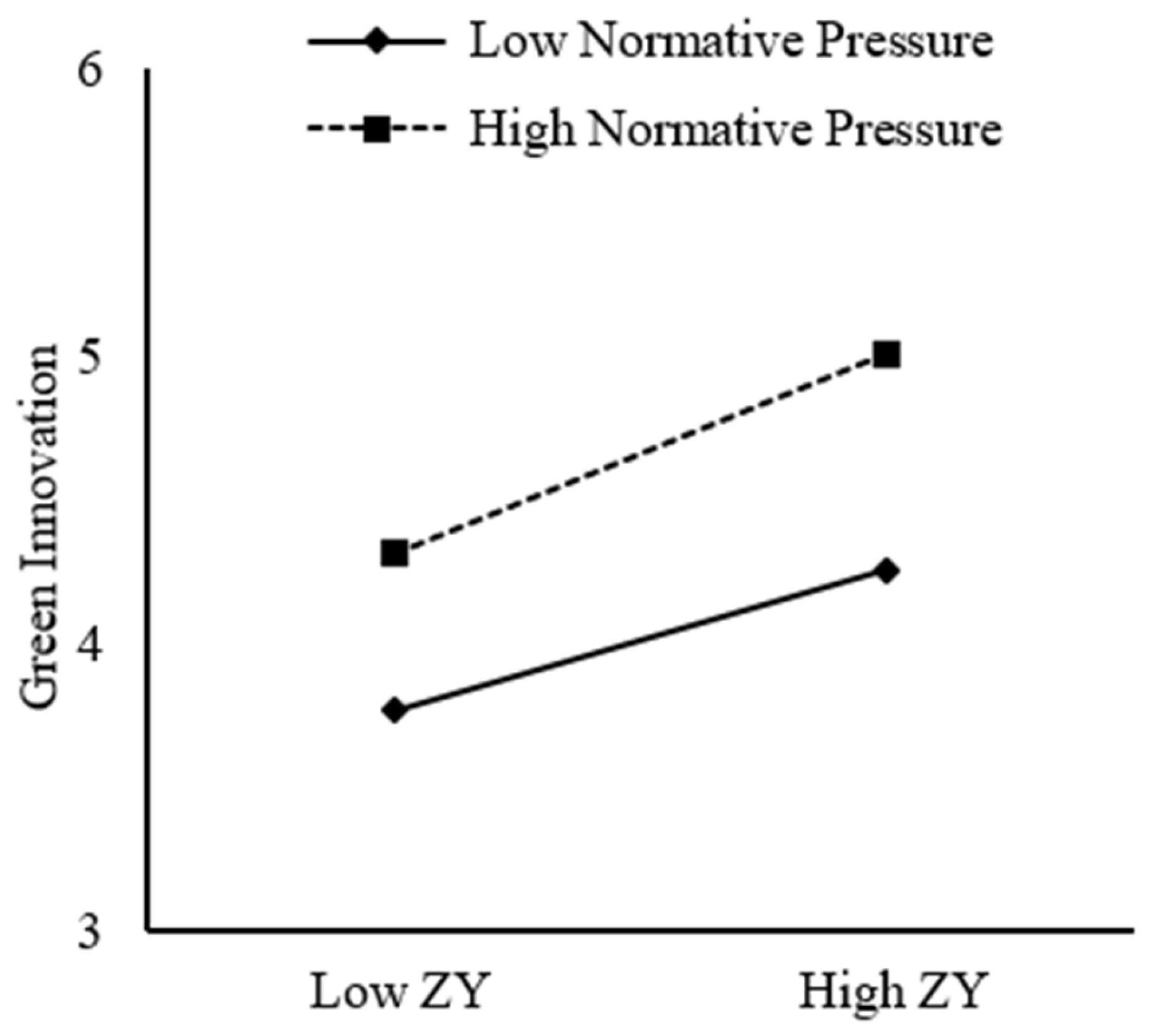

2.4. Institutional Pressure as a Moderating Mechanism

2.5. The Moderating Role of the Nature of Ownership

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measurement of Variables

4. Results

4.1. Validation Factor Analysis

4.2. Common Method Deviation Test

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Research Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Province | Quantity | Province | Quantity | Province | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian | 77 | Sichuan | 4 | Anhui | 8 |

| Guangdong | 67 | Jiangxi | 9 | Tianjin | 2 |

| Zhejiang | 18 | Yunnan | 3 | Hunan | 6 |

| Shanghai | 15 | Hebei | 9 | Beijing | 9 |

| Guangxi | 3 | Shandong | 10 | Shanxi | 3 |

| Henan | 12 | Jiangsu | 12 | Hubei | 5 |

| Jilin | 3 | Hainan | 2 | Shanxi | 3 |

| Ningxia | 2 | Liaoning | 5 | Chongqing | 3 |

| Neimenggu | 2 | Heilongjiang | 3 | others | 3 |

Appendix B

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | GI | GI | GI | GI |

| ZY | 0.598 ** | −0.027 | −0.163 | |

| (0.084) | (0.292) | (0.185) | ||

| Staff | 0.056 * | 0.237 * | 0.114 | 0.115 |

| (0.03) | (0.115) | (0.110) | (0.118) | |

| Year | −0.077 + | −0.440 | −0.382 + | −0.362 |

| (0.0447) | (0.269) | (0.226) | (0.271) | |

| Ownership | −0.097 * | 0.004 | 0.05 | −0.012 |

| (0.043) | (0.093) | (0.084) | (0.090) | |

| Industry | −0.034 ** | −0.066 | −0.021 | −0.038 |

| (0.010) | (0.203) | (0.189) | (0.208) | |

| Location | 0.011 + | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| NP | −0.107 | |||

| (0.278) | ||||

| ZY × NP | 0.126 + | |||

| (0.073) | ||||

| CP | −0.166 | |||

| (0.186) | ||||

| ZY × CP | 0.145 ** | |||

| (0.047) | ||||

| Constant | 4.022 ** | 1.622 ** | 2.544 * | 3.005 ** |

| (0.203) | (0.491) | (1.143) | (0.786) | |

| Observations | 302 | 302 | 302 | 302 |

| R-squared | 0.096 | 0.359 | 0.464 | 0.425 |

Appendix C

| SOEs (N = 93) | Non-SOEs (N = 209) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Variables | GI | GI | GI | GI |

| ZY | 0.864 ** | 0.525 ** | ||

| (0.310) | (0.089) | |||

| Staff | 0.054 | 0.268 | 0.075 * | 0.184 |

| (0.065) | (0.521) | (0.029) | (0.121) | |

| Year | −0.111 | −0.205 | −0.109 * | −0.489 |

| (0.072) | (0.412) | (0.053) | (0.342) | |

| Industry | 0.009 | 0.396 | −0.057 ** | −0.055 |

| (0.018) | (0.279) | (0.013) | (0.229) | |

| Location | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.007 |

| (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Constant | 3.846 ** | 0.003 | 3.958 ** | 1.969 ** |

| (0.316) | (1.232) | (0.221) | (0.500) | |

| Observations | 93 | 93 | 209 | 209 |

| R-squared | 0.017 | 0.379 | 0.148 | 0.382 |

References

- Hao, Y.; Gai, Z.; Wu, H. How do resource misallocation and government corruption affect green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from China. Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, G.; Razzaq, A.; Guo, Y.; Fatima, T.; Shahzad, F. Asymmetric and time-varying linkages between carbon emissions, globalization, natural resources and financial development in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 6702–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Hao, Y.; Weng, J.-H. How does energy consumption affect China’s urbanization? New evidence from dynamic threshold panel models. Energy Policy 2019, 127, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Gai, Z.; Yan, G.; Wu, H.; Irfan, M. The spatial spillover effect and nonlinear relationship analysis between environmental decentralization, government corruption and air pollution: Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 144183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Hao, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, H.; Ba, N. Digitalization and energy: How does internet development affect China’s energy consumption? Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, N.; Strange, R.; Zucchella, A. Stakeholder pressures, EMS implementation, and green innovation in MNC overseas subsidiaries. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Kim, J.-W. Integrating suppliers into green product innovation development: An empirical case study in the semiconductor industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. Empirical influence of environmental management on innovation: Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Henseler, J.; Leal-Millán, A.; Cepeda-Carrión, G. Mapping the field: A bibliometric analysis of green innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arenhardt, D.; Battistella, L.F.; Grohmann, M.Z. The influence of the green innovation in the search of competitive advantage of enterprises of the electrical and electronic Brazilian sectors. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 20, 1650004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, P.-C.; Hung, S.-W. Collaborative green innovation in emerging countries: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M. Green product innovation: Where we are and where we are going. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, C. General wisdom concerning the factors affecting the adoption of cleaner technologies: A survey 1990–2007. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, S7–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Van der Linde, C. Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate. Dyn. Eco-Effic. Econ. Environ. Regul. Compet. Advant. 1995, 33, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yalabik, B.; Fairchild, R.J. Customer, regulatory, and competitive pressure as drivers of environmental innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Ukko, J.; Rantala, T. Sustainability as a driver of green innovation investment and exploitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liao, G.; Li, Z. Loaning scale and government subsidy for promoting green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.H.; Shuang, Q. CEO’s Academic Experience and Enterprise’s Green Innovation: The Dual Perspective Environmental Attentional location and Industry University Research Cooperation Empowerment. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.D.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X.N.; Lu, N. Female Executive Power and Enterprise Green Innovation. East China Econ. Manag. 2022, 36, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Nisbett, R.E. Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yin, J. Team zhongyong thinking and team incremental and radical creativity. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pian, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, C. The cultural drive of innovative behavior: Cross-level impacts of Leader-Employee’s Zhong-Yong orientation. Innovation 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Sun, C.; Luo, H. The Effects of Zhongyong Thinking Priming on Creative Problem-Solving. J. Creat. Behav. 2020, 55, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ran, M.; Cao, P. Context-contingent Effect of Zhongyong on Employee Innovation Behavior. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.F. Multiplicity of zhong yong studies. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2010, 34, 3–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, B.; Omar, R.; Ye, Y.; Ting, H.; Ning, M. The role of Zhong-Yong thinking in business and management research: A review and future research agenda. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2021, 27, 150–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, W.; Fisher, R.; Young, J.D. Entrepreneurs: Relationships between Cognitive Style and Entrepreneurial Drive. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2002, 16, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler-Smith, E. Cognitive Style and the Management of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.J.; Hird, A. Cognitive Style and Entrepreneurial Drive of New and Mature Business Owner-Managers. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.R.; Aguinis, H. The Too-Much-of-a-Good-Thing Effect in Management. J. Manag. 2011, 39, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ji, L.-J.; Lee, A.; Guo, T. The thinking styles of Chinese people. In Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Michael, H.B., Ed.; Oxford Library of Psychology: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Lin, Y.C. Development of a Zhong-Yong thinking style scale. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2005, 24, 247–300. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ding, S.; Zhang, X. Confucian culture still matters: The benefits of Zhongyong thinking (doctrine of the mean) for mental health. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2016, 47, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, L.-F.; Chu, C.-C.; Yeh, H.-C.; Chen, J. Work stress and employee well-being: The critical role of Zhong-Yong. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 17, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. How Does Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Influence Innovation Behavior? Exploring the Mechanism of Job Satisfaction and Zhongyong Thinking. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Effect Mechanism of Error Management Climate on Innovation Behavior: An Investigation from Chinese Entrepreneurs. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 733741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K.; Zwick, T. Employment impact of cleaner production on the firm level: Empirical evidence from a survey in five European countries. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2002, 06, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, L.; Lai, F. Customer pressure and green innovations at third party logistics providers in China: The moderation effect of organizational culture. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T. How do corporate social responsibility and green innovation transform corporate green strategy into sustainable firm performance? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, H.; Gu, J.; Dou, J. How entrepreneurs’ Zhong-yong thinking improves new venture performance: The mediating role of guanxi and the moderating role of environmental turbulence. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2018, 12, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.-Y. A Self-Regulation Model of Zhong Yong Thinking and Employee Adaptive Performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2017, 14, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, G.Y.; Shen, L.Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Jorge, O.J. The drivers for contractors’ green innovation: An industry perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suasana, I.G.A.K.G.; Ekawati, N.W. Environmental commitment and green innovation reaching success new products of creative industry in Bali. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2018, 12, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J. Hotels’ environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-W.; Li, Y.-H. Green Innovation and Performance: The View of Organizational Capability and Social Reciprocity. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Khastagir, D. Exploring role of green management in enhancing organizational efficiency in petro-chemical industry in India. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovcic, T.; Pekovic, S.; Bouziri, A. The effect of knowledge management on environmental innovation: The empirical evidence from France. Balt. J. Manag. 2015, 10, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Tan, R.R.; Siriban-Manalang, A.B. Sustainable consumption and production for Asia: Sustainability through green design and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, S. Global supply chain integration, financing restrictions, and green innovation: Analysis based on 222,773 samples. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrazi, B.; de Villiers, C.; van Staden, C.J. A comprehensive literature review on, and the construction of a framework for, environmental legitimacy, accountability and proactivity. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, B.H.; Mairesse, J. Exploring the relationship between R&D and productivity in French manufacturing firms. J. Econ. 1995, 65, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, H.; Chen, Z. The driving effect of internal and external environment on green innovation strategy—The moderating role of top management’s environmental awareness. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2019, 10, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Clelland, I. Talking Trash: Legitimacy, Impression Management, and Unsystematic Risk in the Context of the Natural Environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ke, W.; Wei, K.K.; Gu, J.; Chen, H. The role of institutional pressures and organizational culture in the firm’s intention to adopt internet-enabled supply chain management systems. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 28, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Do female directors influence firms’ environmental innovation? The moderating role of ownership type. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.Q.; Qian, T. Business Group Affiliation and the Governance of State-Owned Enterprises. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Tan, D. Environment-strategy co-evolution and co-alignment: A staged model of Chinese SOEs under transition. Strat. Manag. J. 2004, 26, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Lan, H.; Lü, Y. China’s township and village enterprises: Kelon’s competitive edge. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2000, 14, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L. Firm performance, corporate ownership, and corporate social responsibility disclosure in China. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2013, 22, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megginson, W.L.; Netter, J.M. From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization. J. Econ. Lit. 2001, 39, 321–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bar, E.S. A case study of obstacles and enablers for green innovation within the fish processing equipment industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Buijs, P. Strategic ambidexterity in green product innovation: Obstacles and implications. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Y. How does employees’ Zhong-Yong thinking improve their innovative behaviours? The moderating role of person–organisation fit. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 34, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H. An environmental perspective extends market orientation: Green innovation sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Lin, C.P.; Zhang, Z.G.; Ye, B. Specialized knowledge search, management innovation and firm performance: The mod-erating effect of cognitive appraisal. Manag. World 2020, 1, 146–166. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dastmalchian, A.; Bacon, N.; McNeil, N.; Steinke, C.; Blyton, P.; Satish Kumar, M.; Bayraktar, S.; Auer-Rizzi, W.; Bodla, A.A.; Cotton, R.; et al. High-performance work systems and organizational performance across societal cultures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 353–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Lin, C. Do top management teams’ expectations and support drive management innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.C.; Zhang, W.C. Theoretic Foundation of the Existence of State-owned Economy. Jilin Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2002, 5, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zheng, M.; Cao, C.; Chen, X.; Ren, S.; Huang, M. The impact of legitimacy pressure and corporate profitability on green innovation: Evidence from China top 100. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, G.; Jia, Y.; Zou, H. Is institutional pressure the mother of green innovation? Examining the moderating effect of absorptive capacity. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 278, 123957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Xu, A.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, W. Environmental Leadership, Green Innovation Practices, Environmental Knowledge Learning, and Firm Performance. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020922909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Lai, K.-H. Mediating effect of managers’ environmental concern: Bridge between external pressures and firms’ practices of energy conservation in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takalo, S.K.; Tooranloo, H.S.; Parizi, Z.S. Green innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 122474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.P. Managerial and Organizational Cognition: Notes from a Trip Down Memory Lane. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 280–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Research in Cognition and Strategy: Reflections on Two Decades of Progress and a Look to the Future. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 665–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-X.; Hu, Z.-P.; Liu, C.-S.; Yu, D.-J.; Yu, L.-F. The relationships between regulatory and customer pressure, green organizational responses, and green innovation performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.F. A case of attempt to combine the Chinese traditional culture with the social science: The social psychological research of “zhongyong”. J. Renmin Univ. China 2009, 23, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, W.; Tang, F.; Si, H.; Xia, Y. Why do I conform to your ideas? The role of coworkers’ regulatory focus in explaining the influence of zhongyong on harmony voice. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2018, 12, 346–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Chia, R. The effect of traditional Chinese fuzzy thinking on human resource practices in mainland China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2011, 5, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z. The spirit and values of Confucian culture. J. Peking Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 1998, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, A.; Hsu, R.S.; Wang, A.-C.; Judge, T.A.; Barkema, H.G.; Chen, X.-P.; George, G.; Luo, Y.; Tsui, A.S.; Harrison, S.H.; et al. Does West “Fit” with East? In Search of a Chinese Model of Person–Environment Fit. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, W.; Mu, Y.; Qu, R. External Green Pressure, Environmental Commitment and Green Innovation Strategy of Manufacturing Enterprises: The Moderating Role of Organizational Slack. J. Northeast. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 25, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D.; Tang, A.K.Y.; Lai, K.-H. Do firms get what they want from ISO 14001 adoption? An Australian perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H.G.; Chen, X.-P.; George, G.; Luo, Y.; Tsui, A.S.; Malesky, E.; Taussig, M.; Liu, D.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. West Meets East: New Concepts and Theories. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 460–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. State-owned enterprises in China: A review of 40 years of research and practice. China J. Account. Res. 2020, 13, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Fiol, C.M. Fools Rush in? The Institutional Context of Industry Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Category | Quantity | Weight | Items | Category | Quantity | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Properties | High-tech industries | 189 | 62.5% | Gender | Male | 154 | 50.9% |

| Low-tech industries | 113 | 37.4% | Female | 148 | 49% | ||

| 3 years and below | 7 | 2.3% | Location | Fujian | 77 | 25.5% | |

| 3–6 years | 30 | 9.9% | Guangdong | 67 | 22.2% | ||

| Firm Age | 6–10 years | 51 | 16.8% | Zhejiang | 18 | 6.0% | |

| 10 years and above | 214 | 70.8% | Other Provinces | 140 | 46.4% | ||

| Firm Size | Large enterprises | 64 | 21.1% | Education background | High School and below | 11 | 3.6% |

| Medium-sized enterprises | 126 | 41.7% | Diploma | 35 | 11.5% | ||

| Small enterprises | 88 | 29.1% | Bachelor | 188 | 62.2% | ||

| Micro-enterprises | 24 | 7.9% | Master and above | 68 | 22.5% |

| Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model (ZY, CP, NP, GI) | 406.664 | 243 | 1.674 ** | 0.047 | 0.951 | 0.945 | 0.050 |

| Three-factor model (ZY, CP + NP, GI) | 499.054 | 246 | 2.029 ** | 0.058 | 0.924 | 0.915 | 0.055 |

| Two-factor model (ZY + CP, NP + GI) | 763.574 | 248 | 3.079 ** | 0.083 | 0.846 | 0.829 | 0.088 |

| Single-factor model (ZY + CP + NP + GI) | 873.068 | 249 | 3.506 ** | 0.091 | 0.814 | 0.794 | 0.097 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhong-yong thinking α = 0. 895 | When discussing, I will consider the conflicting opinions at the same time | 0.942 | 0.943 | 0.848 |

| I often think about the same thing from different perspectives | 0.909 | |||

| I will listen to all the opinions before I express them | 0.941 | |||

| When I make a decision, I will consider various possible conditions | 0.897 | |||

| I often try to find acceptable opinions in a situation of disagreement | 0.960 | |||

| I often try to find a balance between my own opinions and those of others | 0.889 | |||

| I will adjust my original ideas after considering the opinions of others | 0.879 | |||

| I expect to reach a consensus during the discussion | 0.951 | |||

| I try to incorporate my own opinions into the thoughts of others | 0.895 | |||

| I usually express conflicting opinions in a tactful way | 0.879 | |||

| I will try to reconcile the minority to accept the majority in a harmonious way | 0.901 | |||

| I usually consider the harmony of the organizational climate before making a decision | 0.954 | |||

| I usually adjust my behavior for overall harmony | 0.965 | |||

| Coercive pressure α = 0. 897 | Businesses face the threat of legal action if they do not meet legal pollution standards | 0.800 | 0.865 | 0.617 |

| Businesses realize that environmentally irresponsible behavior can trigger fines and penalties | 0.742 | |||

| Consequences for companies that violate environmental laws may include a notification from government departments | 0.803 | |||

| If it fails to comply with national environmental laws and regulations, the company would face serious consequences | 0.795 | |||

| Normative pressure α = 0.843 | Industry market trade associations/professional associations encourage environmental behavior in business | 0.768 | 0.847 | 0.648 |

| Customers expect companies in our industry to be environmentally responsible | 0.824 | |||

| Environmental responsibility is a fundamental requirement for companies to enter the market in this sector | 0.823 | |||

| Green Innovation α = 0. 774 | Our company uses materials with little or no contamination/toxicity | 0.694 | 0.793 | 0.505 |

| Our company improves and designs environmentally friendly packaging for existing and new products | 0.701 | |||

| Our company uses cleaner technologies to save pollution | 0.742 | |||

| Our company recovers and recycles our end-of-life products | 0.705 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ZY | 4.021 | 0.545 | 0.921 | |||||||

| 2. NP | 3.893 | 0.670 | 0.428 ** | 0.805 | ||||||

| 3. CP | 4.108 | 0.592 | 0.556 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.785 | |||||

| 4. GI | 3.637 | 0.681 | 0.512 ** | 0.548 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.710 | ||||

| 5. Staff | 3.394 | 1.499 | 0.206 ** | 0.306 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.149 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. Year | 3.563 | 0.765 | 0.117 * | 0.0900 | 0.0550 | 0.00400 | 0.440 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. Ownership | 1.940 | 0.902 | −0.165 ** | −0.267 ** | −0.266 ** | −0.175 ** | −0.309 ** | −0.134 * | 1 | |

| 8. Industry | 5.742 | 4.016 | −0.222 ** | −0.126 * | −0.0910 | −0.197 ** | 0 | −0.069 | 0.002 | 1 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZY | 0.603 ** | −0.162 | −0.018 | |

| (0.084) | (0.184) | (0.290) | ||

| CP | −0.163 | |||

| (0.185) | ||||

| CP x ZY | 0.145 ** | |||

| (0.047) | ||||

| NP | −0.097 | |||

| (0.278) | ||||

| NP × ZY | 0.124 + | |||

| (0.072) | ||||

| Staff | 0.066 * | 0.247 * | 0.117 | 0.121 |

| (0.026) | (0.115) | (0.118) | (0.110) | |

| Year | −0.083 + | −0.439 | −0.360 | −0.381 + |

| (0.046) | (0.272) | (0.271) | (0.226) | |

| Industry | −0.035 ** | −0.058 | −0.035 | −0.015 |

| (0.010) | (0.205) | (0.209) | (0.190) | |

| Ownership | −0.107 ** | −0.011 | −0.016 | 0.040 |

| (0.043) | (0.090) | (0.087) | (0.081) | |

| Constant | 4.113 ** | 1.637 ** | 3.002 ** | 2.521 * |

| (0.199) | (0.491) | (0.786) | (1.143) | |

| Observations | 302 | 302 | 302 | 302 |

| R-squared | 0.086 | 0.357 | 0.424 | 0.463 |

| SOEs (N = 93) | Non-SOEs (N = 209) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

| ZY | 1.037 ** | 0.561 ** | ||

| (0.338) | (0.102) | |||

| Staff | 0.056 | −0.738 * | 0.072 ** | 0.201 |

| (0.074) | (0.379) | (0.029) | (0.128) | |

| Year | −0.104 | 0.046 | −0.072 | −0.530 |

| (0.084) | (0.368) | (0.0543) | (0.344) | |

| Industry | −0.005 | 1.296 ** | −0.054 ** | 0.018 |

| (0.022) | (0.197) | (0.014) | (0.250) | |

| Constant | 3.956 ** | −0.698 | 3.921 ** | 1.808 ** |

| (0.409) | (1.315) | (0.223) | (0.559) | |

| Observations | 93 | 93 | 209 | 209 |

| R-squared | 0.015 | 0.403 | 0.106 | 0.361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, M.; Khattak, S.I. Bridging the Great Divide: Investigating the Potent Synergy between Leadership, Zhong-Yong Philosophy, and Green Innovation in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129187

You C, Zhao Z, Yu M, Khattak SI. Bridging the Great Divide: Investigating the Potent Synergy between Leadership, Zhong-Yong Philosophy, and Green Innovation in China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129187

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Chengde, Ziwen Zhao, Mengyuan Yu, and Shoukat Iqbal Khattak. 2023. "Bridging the Great Divide: Investigating the Potent Synergy between Leadership, Zhong-Yong Philosophy, and Green Innovation in China" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129187