1. Introduction

Ishigaki City is approximately 410 km southwest of Okinawa’s main island and 1900 km from Tokyo. It is the southernmost city in Japan [

1,

2]. Ishigaki Island, the city’s political, economic and transportation centre, has experienced a surge in tourism since 2013 when the new airport was built [

3,

4]. The number of tourists has exceeded one million per year [

5]. Statistics show that the areas most frequented by residents and tourists fall under the Urban Tourism Green Spaces (UTGSs) category [

6], including beaches, bays, parks, and traditional gardens in or around the city. These areas, with their rich diversity, relative accessibility, and distinctive geographical features, are among the most important factors in shaping the perception and brand value of tourism in Okinawa [

7]. The public space with natural and managed vegetation is the primary tourist asset of Ishigaki. This city’s tourism image and value are also world-renowned owing to its unique regional attraction, the marine landscape, and the UTGSs [

8]. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, Ishigaki, relying on the tourism industry as its main economic driver, faces significant challenges in the future recovery of tourism. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the changes in tourist behaviour by studying their utilisation of UTGSs during the crisis. The findings of this research will be particularly valuable for urban planners and tourism operators as the findings can inform the development of effective crisis response strategies and guide the sustainable development and attractiveness of urban tourism areas [

9,

10].

A series of negative factors at the tourism industry level emerged to control the spread of COVID-19, including immigration control policies in various countries, temporary closures of public places, policies restricting business activities, and public concerns about the safety of accessing public spaces [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Several studies have indicated that the impact of multiple extraordinary factors, such as reduced human activities during the pandemic, changes in the ecosystem, and the public’s willingness to seek relief from prolonged closure policies, has changed people’s use of green spaces in tourist cities [

15,

16]. As the vaccine became available and awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic grew, countries gradually began to lift the embargo, and the tourism industry began to recover [

17]. During this period, the Japanese government introduced measures to promote GOTO tourism [

4,

18]. However, there have since been significant changes compared to past experiences [

19]. The return to normal economic life under repeated pandemics in the future will inevitably differ from the period of strict restrictions in the last two years [

20], constituting a completely new issue for the tourism industry to adapt to.

Visitors’ use of an area over time is characterised by their overall perceived preferences for it and its natural landscape [

21]. Several studies have shown that the results of collecting and listening to a wide range of visitor-generated data, capturing the changing needs of visitors, and assessing the actual use of urban green spaces from a user’s perspective can directly reflect the effectiveness of the planning, design, and management of urban green spaces [

22,

23,

24,

25]. This study focuses on the urban tourism green areas that best represent the tourist image and value of Ishigaki City [

26] and explores the changes in the use and causes of the tourism green areas from the tourist perspective before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, there were 1.27 million annual visitors to Ishigaki City [

27], and big data research is increasingly important for many tourists [

28]. Tourism situational awareness based on big data provides a scientific reference for predicting tourists’ behavioural intentions, improving tourism satisfaction and optimising tourism green spaces in tourist cities [

7].

As a new information environment consisting of open big data on the Internet gradually emerges, User-Generated Content (UGC) is increasingly regarded as a trusted form of information dissemination [

29,

30]. The study of UGC is publicly available on travel review platforms and is characterised by large sample size, timeliness, and diversity compared to traditional data. It is more advantageous in capturing individual behaviour, research depth, and trend prediction [

31,

32].

Research based on big data tools to understand tourists’ use and evaluation of urban green spaces is currently focused on obtaining web data of UGC. For example, Zhang and Zhang manually collected review data about Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden from Chinese tourism websites and built an IPA model to analyse tourists’ use of different areas within the botanical garden [

33]. Zhu and Xu used Sina Weibo sign-in data based on correlation analysis to assess the use of urban green spaces in Beijing during COVID-19 [

34]. Most studies of urban green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic have explored the potential impact of urban green spaces on the physical and mental health of residents because of the pandemic closure policy. For example, Lopez et al. [

35] analysed data from an online survey to demonstrate the use of urban green spaces in New York City during the pandemic and the health benefits they provided to residents. Jato-Espino et al. [

36] used data from a questionnaire to conduct a correlation analysis to explore the beneficial social effects provided by green infrastructure during the strict Spanish embargo. Studies exploring the direction of urban green space planning in the post-pandemic era have stemmed from Li and Li’s [

37] views on the need for prevention and control under the pandemic, such as zoning, route guidance, and planting special vegetation, and Fu et al.’s [

38] views on the importance of public green space from the perspective of urban park management and planning accordingly. Most recent studies on urban green spaces focus on the special period of strict closure during the pandemic and lack studies on overall development. The use of questionnaires can often only capture data at that point, making it difficult to analyse changes in their characteristics over a longer timeline. Thus, future perspectives on UTGSs tend to focus on the need for pandemic prevention and crisis response and less on the normative needs of experience. Existing studies have shown that the most popular activities among urban residents in UTGS utilisation are sports and relaxation. Despite the travel restrictions imposed during the pandemic, residents have demonstrated an increased diversity in UTGS usage. Additionally, there is a clear preference for outdoor activities and a tendency to avoid densely populated areas [

39,

40]. However, the aforementioned studies primarily focus on the usage patterns of urban residents around green spaces and pay less attention to tourists’ perspectives. While countries are gradually lifting the restrictions imposed due to the pandemic, there remains a possibility of future outbreaks of COVID-19 or similar crises [

20]. For tourism-dependent cities facing significant industry crises due to the impact of the pandemic, it is crucial to better understand the behavioural changes of tourists during crisis periods. This understanding will serve as an important foundation for future policy-making efforts. Understanding changes in tourist demands and preferences can guide crisis management, product development, marketing strategies, and sustainable development in the tourism industry [

30,

31]. Adapting strategies to boost tourist confidence; introducing safe travel products; exploring new destinations; targeting emerging interests in promotional efforts; promoting health, safety, and environmental certifications; and community involvement are essential for industry recovery [

23,

27]. Research findings provide crucial insights for decision making, ensuring safer and more sustainable tourism industry growth and preventing the complete standstill caused by crises, thus enhancing its sustainability.

Given the above background, this study chose Ishigaki City as a case study and collected online review data in Python, which contained information on the multiple uses of the tourism green space in Ishigaki City. We investigated the independence and relative change of the multiple-use status between different periods and the results of text mining of the reviews to understand the similarities and differences in tourists’ experience of the green space in Ishigaki City before and during the pandemic.

3. Results

3.1. Raw Data Acquisition Results

The raw data were collected from the earliest full year in which review information of the study subjects appeared on the TripAdvisor website to the full year in 2021 (January 2009 to December 2021), ensuring uniformity in the time-seasonal variables and spanning a total of 13 full years and 156 months. The post-2022 period can be considered as the post-pandemic recovery period for the tourism industry; therefore, the periods covered in this study are the pre-pandemic period (January 2009–December 2019) and the prevention and control period (January 2020–December 2021) [

48].

A total of 5569 raw data were obtained through crawling, including 5348 and 231 pieces before and during the pandemic, respectively. The year-by-year counts of the raw data and the number of inbound tourists to Ishigaki City for each year are shown in

Table 1. A bivariate correlation analysis was conducted using SPSS 25 for the year-by-year counts of the raw data and the number of tourists entering the area over the years in Ishigaki City, and the Sig. (2-tailed) value was calculated to be less than 0.01. Thus, the above bivariate correlation was significant. The amount of information and the overall number of tourists show a significant positive correlation.

3.2. Independence Test Results

The variables such as rating, type of travel, time of travel, type of green space, and tourist travel experience are likely to show some regular changes. During the pandemic, these regular patterns may also change in response to tourism policies, closure regulations, and security concerns [

5].

This study is the first to put forward the hypothesis that the utilisation variables of tourists present independence among themselves. Based on the review information data before and during the pandemic [

52], the two utilisation variables were crossed to establish the Pearson chi-square test (

Appendix A and

Appendix B). Their Sig. (two-tailed) values were calculated as shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The test results showed that the Sig. (two-tailed) values between rating and type of travel, rating and time of travel, and type of green space and tourist travel experience for the above three groups of two variables before the pandemic were greater than 0.05. Thus, the hypothesis of independence cannot be rejected and cannot be judged to have regular variation.

As for rating and type of green space, rating and tourist travel experience, type of travel and time of travel, type of travel and type of green space, type of travel and tourist travel experience, type of green space and time of travel, tourist travel experience and time of travel, the Sig. (2-tailed) values between the two variables of the above seven groups were less than 0.01, demonstrating that they could be extremely correlated. Thus, the independence assumption could be overturned. The regular changes between the two elements of utilisation status could be observed using a histogram group.

In the period following the pandemic, the Sig. (2-tailed) values between the two variables of the following four groups were greater than 0.05: rating and type of travel, type of green space and type of travel, type of green space and tourist travel experience, tourist travel experience and time of travel. Thus, the hypothesis of independence cannot be rejected and cannot be judged to have regular variation.

The Sig. (2-tailed) values between rating and tourist travel experience were in the range of 0.05 and 0.01. The Sig. (2-tailed) values between the following five groups of two variables were less than 0.01, so they are considered highly correlated: rating and time of travel, rating and type of green space, type of travel and time of travel, type of green space and time of travel, type of travel, and tourist travel experience. Thus, the independence hypothesis can be overturned for these six groups of two variables. Observing the regular changes between the two elements of utilisation status is possible through a multi-linear line graph. The multi-linear line graph allows us to observe the regular changes between the two elements of the utilisation situation.

3.3. Results of the Relative Change Relationships and Analysis

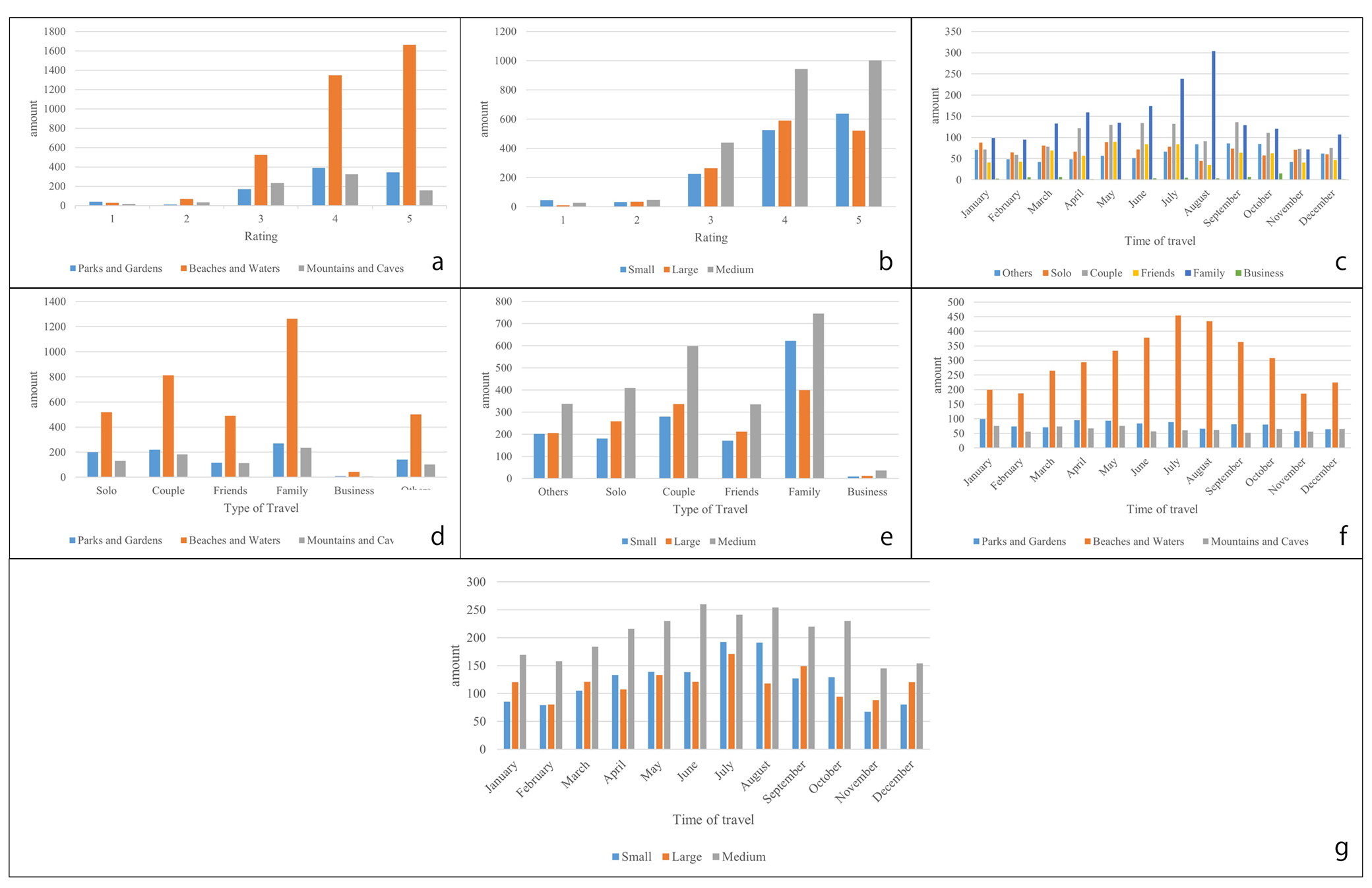

The results of creating histogram groups for both combinations of the two utilising variables before and after the pandemic are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, and the regular changes are thus observed.

3.3.1. Before the Pandemic

Rating and type of green space:

Figure 1a demonstrates that the number of visitors to Beaches and Waters before the COVID-19 pandemic was significant. Both Beaches and Waters and Parks and Gardens had a generally high level of satisfaction, with the highest percentage of positive ratings of 4–5 for Beaches and Waters (Beaches and Waters: 82.93%; Parks and Gardens: 76.83%; Mountains and Caves: 62.58%). Ratings for Mountains and Caves were mostly concentrated in the 3–4 range, with significantly lower satisfaction levels than the other two categories.

Rating and tourist travel experience:

Figure 1b indicates that before the COVID-19 pandemic, a positive rating of 4–5 was predominant among tourists with different travel experiences with only those with high travel experience having a 5 count lower than 4. It is more difficult to obtain the ultimate satisfaction for the more experienced tourist group. This reflects a lack of uniqueness and professionalism in the area.

Type of travel and time of travel:

Figure 1c shows that before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of tourists travelling as a Family and Couple was significantly higher, while the number of commercial businesses was very low. The summer school holidays are in August in Japan, so there is a significant increase in the number of families travelling with children. Meanwhile, those who do not need to bring children presumably cancel their travel plans due to the increase in flight and hotel prices or the most uncomfortable climate in August.

Type of travel and type of green space:

Figure 1d demonstrates that before the COVID-19 pandemic, all tourists showed a significant preference for Beaches and Waters as a tourist destination, with the number of tourists decreasing for each type of attraction in the order of Family, Couple, Solo, Friends and Business.

Type of travel and tourist travel experience:

Figure 1e shows that before the COVID-19 pandemic, families accounted for the largest proportion of all tourists. However, as the tourist travel experience increased, the proportion of families significantly weakened. However, the proportion of families decreases for the higher tourist travel experience (low: 42.46%; medium: 30.27%; high: 28.06%). Meanwhile, the proportion of Solos increased (low: 12.35%; medium: 16.62%; high: 18.14%), and the distribution of different travel types became more balanced.

Type of green space and time of travel:

Figure 1f displays that before the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of visitors choosing Beaches and Waters peaked in July, with a significant peak in the summer months (March–October). The distribution between Parks and Gardens and Mountains and Caves was more balanced across all periods.

Tourist travel experience and time of travel:

Figure 1g demonstrates that before the COVID-19 pandemic, all visitors showed peak travel times during the summer months (March–October), with lows in February and November. High tourist travel experience tended to significantly differ from other tourists during the peak travel period in August.

3.3.2. During the Pandemic

Ratings and tourist travel experience:

Figure 2a shows that after the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of negative ratings of 1–2 was significantly higher among tourists with low travel experience compared to those before the pandemic (before: 5.32%; after: 15%). The proportion of tourists with a full rating of 5 increased (before the pandemic: 36.71%; during the pandemic: 43.21%).

Rating and time of travel:

Figure 2b shows that positive ratings of 4 and 5 were significantly higher in August, March, and January after the COVID-19 pandemic, with 3 ratings being the highest in March and 2 and 3 ratings being relatively high in November.

Rating and type of green space:

Figure 2c demonstrates that the positive rating of 4–5 for Beaches and Waters was generally consistent after the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (pre-pandemic: 82.93%; post-pandemic: 84.17%) with a significantly higher percentage of full 5 ratings (pre-pandemic: 45.80%; post-pandemic: 50.83%). The positive rating of 4–5 for Parks and Gardens decreased significantly (pre-pandemic: 76.83%; post-pandemic: 61.67%). Meanwhile, the positive rating of 4–5 for Mountains and Caves increased significantly (pre-pandemic: 62.58%; post-pandemic: 75.61%).

Type of travel and time of travel:

Figure 2d shows that after the COVID-19 pandemic, Solo travel peaked in March, Couple travel peaked in March and August, and both Family and Friend travel peaked in August. March and August.

Type of green space and time of travel:

Figure 2e displays that after the COVID-19 pandemic, Beaches and Waters showed a significant surge in visitors in August, Parks and Gardens in March, and Mountains and Caves in January. Beaches and Waters did not show a continuous peak period of visitation during the summer months (March–October) compared to the pre-pandemic period. Visits to Parks and Gardens and Mountains and Caves fluctuated significantly throughout the year.

Type of travel and tourist travel experience:

Figure 2f indicates that after the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of Family travel was significantly lower for all tourists (low Pre-pandemic: 42.46%; low post-pandemic: 25%) compared to pre-pandemic (medium Pre-pandemic: 30.27%; medium Post-pandemic: 16%) (high Pre-pandemic: 28.06%; high Post-pandemic: 9.88%). The choice of Solo travel mode increased among those with medium travel experience and overtook the Family travel mode to reach the highest percentage. The Couple mode has surpassed the Family mode to reach the highest number of travellers with a high travel experience.

3.4. Text Mining Results and Analysis

The above-mentioned independence tests and bivariate analysis show that the years 2020–2021 were affected by the domestic emergency policy on pandemic control and restrictions on international tourist arrivals in Japan [

48]. Moreover, the amount of data collected on the reviews of Overseas Visitors during the pandemic was minimal. To ensure the feasibility and reliability of the analysis and to avoid the bias caused by the extreme sample differences of Overseas Visitors during the pandemic prevention and control period, only the review texts of domestic Japanese tourists were used in this text-mining study. The KH Coder 3 software is currently the most widely used for Japanese text mining, and its results are trusted by a wide range of scholars [

54].

The high-frequency nouns and adjectives of the green space experience themes before and during the pandemic are shown in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9. In the co-occurrence network, the keywords in the circles are connected by lines to illustrate the relevance. The larger the area of the circle, the more frequently the word appears in the source text, and the thicker the line connecting the two circles, the closer the relationship between the two subject words [

55].

3.4.1. The 1–2 Point Negative Evaluation Group before and during the Pandemic

Comparing the high-frequency words for the green space experience theme (

Table 4 and

Table 5) for the 1–2-point negative evaluation group before and during the pandemic revealed a large difference, with three recurring high-frequency nouns and four high-frequency adjectives.

Before and during the pandemic, the term “stalactite cave” appeared predominantly, indicating that compared with other scenic spots, stalactite caves are more likely to cause negative emotions in tourists. Before the pandemic, there were more diverse scenes, such as “beach” and “glass boat”. Moreover, “animal” appeared in second place, indicating that animal-related experiential activities in the region caused serious negative emotions for visitors. During the pandemic, only one specific scene, “park”, appeared, indicating that pandemic prevention policies greatly restricted the development of tourism projects, causing extremely negative emotions for visiting tourists [

56]. Regarding facilities and management, “pamphlets”, “signboards”, and “parking” appeared before the pandemic, while “abandoned” and “maintenance” appeared during the pandemic. This indicated that the region has long had deficiencies in guiding and signage. Concerning pricing, “entrance fee” appeared before the pandemic, and “worth” and “price” appeared during the pandemic. This indicated that before the pandemic, dissatisfaction with costs was mainly directed at ticket prices. In contrast, during the pandemic, negative thoughts focused on the overall value of the journey. Regarding emotional expression, more specific negative feelings were expressed about the environment during the pandemic, such as “horror” and “dark”.

Comparing the co-occurrence networks (

Figure 3), before the pandemic, the negative reviews mainly focused on high entrance fees, as indicated by the connections between “stalactite cave”, “high”, “entrance fee”, and “Ishigaki”. There were also complaints about amusement activities that did not meet visitors’ expectations, as indicated by the connections between “disappointment”, “glass boat”, “Ishigaki Island”, and “pamphlet”, and unclear signage, as indicated by the connections between “parking”, “signboard”, and “entrance”.

During the pandemic, the negative reviews focused on the lack of child-friendly facilities, as indicated by the connections between “kid”, “child”, “horror”, “dark”, and “passageway”. There were also complaints about facilities being closed for maintenance or abandoned, as indicated by the connections between “maintenance”, “abandoned”, “deposition”, “store”, and “preliminary investigation”. Additionally, there were doubts about the overall value of the Ishigaki trip, as indicated by the connections between “map”, “funny story”, “Ishigaki Island”, and “worth”.

3.4.2. The 3-Point Neutral Evaluation Group before and during the Pandemic

Comparing the high-frequency words of the green space experience theme (

Table 6 and

Table 7) for the 3-point neutral evaluation group before and during the pandemic, the difference between the two groups was reduced compared to the negative evaluation group, with six recurring high-frequency nouns and three high-frequency adjectives.

Before and during the pandemic, certain locations such as “stalactite caves”, “beaches”, and “parks” appeared. Before the pandemic, aquatic scenes such as “glass boat” and “Kabira Bay” were present, while during the pandemic, “dam” and “square” emerged, with “park” ranking second. This suggests that the probability of tourists visiting unmanaged sites increased during the pandemic [

57]. Regarding facilities and management, “parking” was repeatedly mentioned before and during the pandemic, while “maintenance” emerged during the pandemic. This indicates that parking has always been a concern for tourists, and closures and renovations during the pandemic received negative evaluations from tourists. Regarding emotional expressions, similar to the previous group, “disappointment” was mentioned before the pandemic, while “peace”, “nature”, and “view platform” emerged during the pandemic. This suggests that the tourism industry was less vibrant during the pandemic, and tourists could enjoy greater tranquillity in viewing natural scenery. However, some tourists did not respond positively to this.

Comparing the co-occurrence network (

Figure 4), before the pandemic, neutral evaluations were most prominently reflected in the connections between “glass boat”, “disappointment”, “Kabira Bay”, “beach”, “pretty”, “scenery”, “park”, “wide”, “view platform”, and “site”. This represents the glass boat ride attraction, indicating that the surrounding ocean scenery was excellent.

During the pandemic, neutral evaluations were mainly reflected in the connections between “dam”, “prayer”, “peace”, “yaeyama”, “Ishigaki Island”, and “nature”, representing the natural mountainous environment around the dam that inspired awe in tourists. In addition, connections between “maintenance”, “installation”, “space”, “square”, “park”, and “wide” represented public spaces undergoing renovations, which generated widespread dissatisfaction among tourists.

3.4.3. The 4–5 Point Neutral Evaluation Group before and during the Pandemic

Comparing the high-frequency words for the green space experience theme (

Table 8 and

Table 9) for the 4–5-point positive rating group before and during the pandemic revealed a small difference, with eight recurring high-frequency nouns and five high-frequency adjectives.

Before the pandemic, “weather” appeared in the keywords, suggesting that due to the variety of tourism activities available, tourists were more susceptible to the impact of weather conditions [

58]. Thus, they paid more attention to changes in weather. During the pandemic, “stalactite cave” appeared in the keywords, and the frequency of “park” significantly increased. Based on the previous set of ratings, it can be inferred that with the restrictions on tourism activities, there was a significant increase in the proportion of tourists visiting caves and public green spaces during the pandemic. Regarding emotional expression, “blue” and “transparent” were repeated in both sets of keywords, reflecting the seawater’s clearness.

Comparing the co-occurrence network (

Figure 5), before the pandemic, positive evaluations were mainly reflected in the water-based entertainment activities, such as “glass boat”, “coral”, “Kabira Bay”, “sightseeing”, “pretty”, and “scenery”, which relied on the excellent marine landscape resources. During the pandemic, positive evaluations mainly revolved around the natural landscape viewing experience, centred around “Ishigaki Island” and “view platform” and connected around “sandy” and “Kabira Bay”. Compared to before the pandemic, the association between the “glass boat” water-based entertainment activity and other words weakened, indicating the uncertainty of entertainment activities due to the impact of pandemic prevention policies.

4. Discussion

The results show that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a marked change in the status of tourists’ use and experience of Ishigaki’s tourism green spaces. Moreover, the pandemic prevention policy has led to a severe impact on global tourism and a reduction in tourism activities, and it has had an impact on tourist evaluation feedback.

Based on the results of the analysis of the data before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the prevention and control period in Japan, before the pandemic, tourists expressed high praise for the tourism green areas in Ishigaki City. Furthermore, tourists highly valued the natural beauty of Ishigaki Island such as the sea view, scenery, and beaches, and it received more extensive recognition from overseas tourists. The main areas of dissatisfaction during this period were the high entrance and parking fees. There was also a lack of clarity in the signage and much criticism from visitors regarding the ecology of the animals and human interaction. Although the weather is uncontrollable, providing prepared tours for visitors from far away in bad weather conditions should also be a future planning issue.

Visitors’ satisfaction remained high during the outbreak; this could be because of the psychological relief during the difficult period and because tourist programs were not as crowded and overly commercialised as before, allowing visitors to concentrate more on enjoying nature. The main areas of dissatisfaction during this period were the cancellation of tourist programs, the abandonment of facilities, and the lack of management services. Moreover, the huge psychological gap that some visitors experienced during this period may have affected the deterioration of their perception of the entire Okinawa tourism industry.

Most visitors travel in groups, with individual visits concentrated among experienced travellers. For experienced travellers, the area is still lacking in uniqueness and expertise. As most of the tourists are water sports-oriented, they visit the area during the warm period from March to October when they can comfortably visit the sea, with a surge in the number of tourists during the student holidays in August. However, other periods did not have a regular impact on the overall assessment. During the pandemic control period, the number of visitors peaked in March against the trend due to the occasional activity restriction policy. It remains to be seen whether this will be sustainable in the future.

With the mitigation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the gradual relaxation of control measures, several surveys have shown that the tourism industry is recovering rapidly and that Ishigaki’s tourism industry is facing an opportunity to rebuild and recover [

59,

60]. Beaches and Waters are not only the most popular type of green space, but also are receiving the best public ratings. Meanwhile, the Mountains and Caves area, which was previously undeveloped and unmanaged, has enjoyed a significant increase in visitor numbers and ratings. Many popular tourist destinations closed or limited the number of visitors to their planned trips, thus stimulating the possibility and opportunity for visitors to explore the island’s unique natural attractions independently. With the area’s unique mystique and commemorative significance fitting in with the prayerful mindset of the people during the pandemic, there is clear potential for greater use of the area’s tourism resources. In the future, it is possible to move beyond the marine perimeter and to consider maintaining and establishing safety measures and giving visitors a certain amount of freedom to explore the area without compromising the pleasure of experiencing nature.

Numerous studies have highlighted changes in the utilisation of urban green spaces across different regions during the pandemic. Surveys conducted in European cities have shown a high level of appreciation for urban green spaces, despite a reduction in visits due to government restrictions. The main motivations for visiting these spaces have been physical exercise and relaxation, with respondents in Italy and Lithuania also expressing an appreciation for nature observation. As an alternative, some people turned to streets and city gardens during the pandemic. The findings also emphasise the importance of greenery for the biophilic nature of urban dwellers and the need for a diverse range of urban green space types [

40].

Furthermore, studies conducted in Guangzhou, China, which is in the same subtropical region as Ishigaki and shares the East Asian cultural sphere, have shown a more positive sentiment towards the use of urban green spaces during the COVID-19 epidemic. People tend to prefer urban green spaces with natural water or mountains and lower population density during a pandemic. There is also a tendency to visit green spaces on weekdays rather than weekends due to changes in lifestyles. Urban green spaces with a religious attribute, where residents are allowed to pray for their health, are also more popular than elsewhere [

61].

Comparing the above studies reveals a common trend in the use of urban green spaces during the epidemic in European cities, Guangzhou, China, and Ishigaki, Okinawa. People prefer urban green spaces that are less densely populated and offer a good natural environment, with physical exercise, relaxation, and emotional comfort being the main motivations for visiting. European countries are more inclined to provide venues for achieving physical fitness, while people in East Asia tend to visit green spaces of a religious nature that provide psychological comfort. European cities and Guangzhou, China, have experienced high levels of urban development and actively sought urban alternatives to green spaces during the epidemic. However, Ishigaki’s island hinterland still has a large amount of undeveloped natural landscapes that can provide a new tourism experience during special circumstances.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a change in visitor perceptions of the use and experience of the Ishigaki tourism green space. In the aftermath of the pandemic, due to the timing of the pandemic prevention policy and the uncertainty of a successful tourism programme, the proportion of visitors visiting the area during periods when water activities were not suitable increased significantly. Visitors prefer to enjoy the types of green space within the island that were expected to have a low density of people, separated by natural mountains and forests, or open public spaces, rather than the extreme appreciation of the marine landscape and water activities of the past. During the pandemic, the psychologically comforting properties of tourism green spaces also influenced visitor use, with sites containing monumental facilities that offer prayers for good health becoming more popular. This suggests that during future crises, urban tourism green spaces can attract visitors by offering a safe, tranquil, and emotionally comforting environment. Furthermore, the research findings provide valuable insights for future tourism development. Inland areas of islands, natural mountains and forests with low population density, and open public spaces can become new tourism resources. These areas can offer unique tourism experiences that combine close interaction with nature and emotional fulfilment through proper planning and management. In future tourism development, emphasis can be placed on the enhancement and promotion of these areas to attract more visitors and foster sustainable tourism development. Additionally, the study found that overall, tourist satisfaction with green spaces was higher during the pandemic prevention and control period. This further confirms the positive impact of urban tourism green spaces on tourists’ psychological well-being and emotional solace. Therefore, it is important for urban planners and tourism management organisations to recognise and protect the value of urban tourism green spaces, providing comfortable and enjoyable environments for visitors. This will have a positive impact on enhancing sustainable tourism development and brand value in the industry.

Admittedly, neither the data crawling nor the text mining relying on the Japanese text database are perfect, and there is room for improvement. The accuracy of this study relies heavily on that of the data-crawling and text-processing algorithms. Due to the limitations of the author’s ability, the development of this part of the algorithm relies heavily on open-source software. The analysis is mostly based on reports and observational studies during the pandemic without a stable quantitative system. Furthermore, we will extensively collect ample data information after the end of pandemic restrictions. As a future research objective, we aim to evaluate the recovery status of the tourism industry after the conclusion of pandemic restrictions by leveraging integrated advanced modelling techniques, such as time-series models, and provide accurate predictions and insights for future tourism decision making.