The Role of the Forest Recreation Industry in China’s National Economy: An Input–Output Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Input–Output Model

2.2. Linkage Analysis

2.3. Data Source

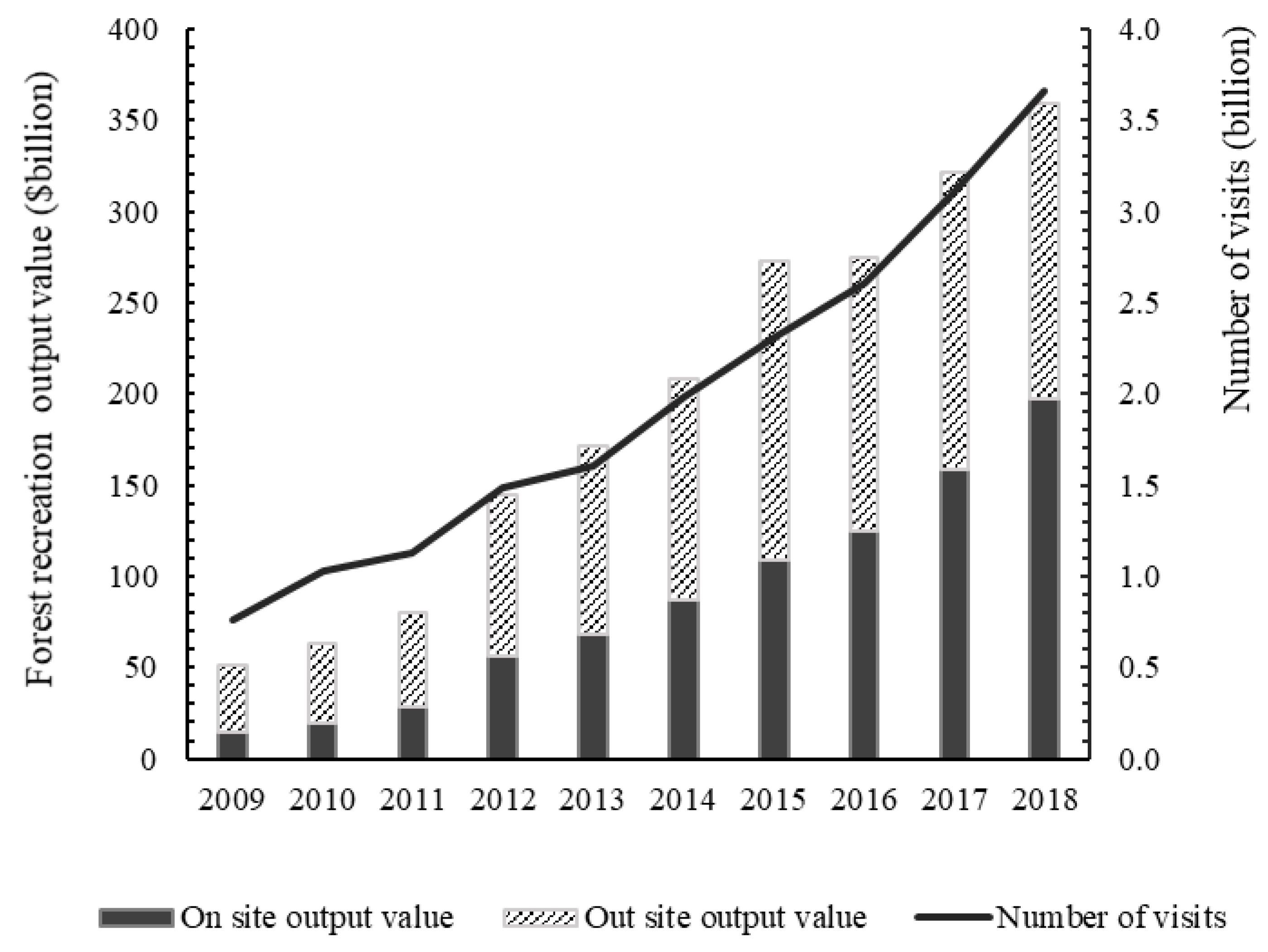

3. Direct Effects of Forest Recreation Industry in China

4. Indirect and Total Effects of Forest Recreation Industry in China

4.1. Inter-Industry Linkage Effect

4.2. Output Effect

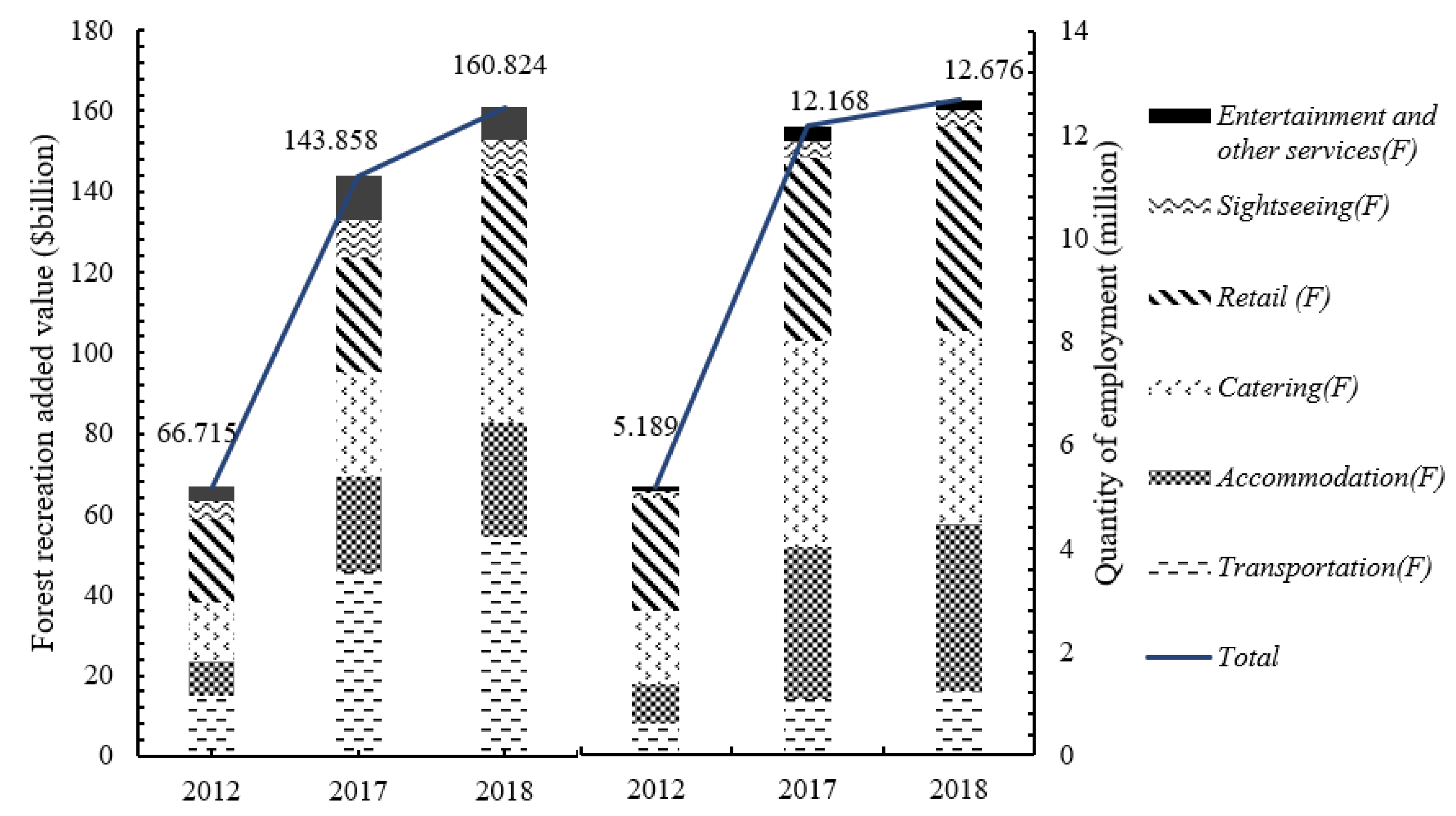

4.3. Added Value and Employment Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Economic Implication

5.2. Employment Implication

5.3. Standard Multipliers

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| NO. | Industry | NO. | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery | 23 | Waste recycling |

| 2 | Coal mining and dressing | 24 | Repair services of metal, machinery, and equipment |

| 3 | Petroleum and gas extraction | 25 | Electricity, and heat production and supply |

| 4 | Metal mining and dressing | 26 | Gas production and supply |

| 5 | Non-metal, and other mining and dressing | 27 | Water production and supply |

| 6 | Food and tobacco | 28 | Construction |

| 7 | Textile | 29 | Wholesale and retail trade |

| 8 | Wearing apparel and leather products | 30 | Transportation, storage, and post |

| 9 | Wood processing and furniture | 31 | Hotel and catering services |

| 10 | Papermaking, printing, and educational and artistic products | 32 | Information transmission, software, and information technology |

| 11 | Petroleum processing, coking, and nuclear fuel processing | 33 | Finance |

| 12 | Chemical products | 34 | Real estate |

| 13 | Nonmetallic mineral products | 35 | Leasing and business services |

| 14 | Metal smelting and rolling processing | 36 | Research and technical services |

| 15 | Metal products | 37 | Water conservancy, environment, and public facilities management |

| 16 | General equipment | 38 | Repair, households, and other services |

| 17 | Special equipment | 39 | Education |

| 18 | Transportation equipment | 40 | Health and social services |

| 19 | Electrical machinery and apparatus | 41 | Culture, sports, and entertainment |

| 20 | Communication equipment, computers, and other electronic equipment | 42 | Public management, social security, and social organization |

| 21 | Instrument and apparatus | 43 | Forest recreation * |

| 22 | Other manufacturing products |

References

- SFA. Practice “Two Mountains Theory” and Promote the Development of Forest Tourism. Available online: http://lyylj.gz.gov.cn/zhzx/tpxw/content/post_3034075.html (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Balmford, A.; Green, J.M.H.; Anderson, M.; Beresford, J.; Huang, C.; Naidoo, R.; Walpole, M.; Manica, A. Walk on the Wild Side: Estimating the Global Magnitude of Visits to Protected Areas. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SFA. During the “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” Period, the Average Annual Number of Tourists in China’s Forest Tourism Reached 1.5 Billion. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-10/19/content_5552291.htm (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Lamsal, P.; Pant, K.P.; Kumar, L.; Atreya, K. Sustainable livelihoods through conservation of wetland resources: A case of economic benefits from Ghodaghodi Lake, western Nepal. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Wang, E.; Yu, Y. Analysis on asymptotic stabilization of eco-compensation program for forest ecotourism stakeholders. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 29304–29320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranah, P.; Lal, P.; Wolde, B.T.; Burli, P. Valuing visitor access to forested areas and exploring willingness to pay for forest conservation and restoration finance: The case of small island developing state of Mauritius. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, S.; Spiteri, A. Linking livelihoods and conservation: An examination of local residents’ perceived linkages between conservation and livelihood benefits around Nepal’s Chitwan National Park. Environ. Manag. 2011, 47, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green. Developing forest tourism to help out of poverty. Land Green. 2021, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, N.; Wang, E.; Yu, Y. Valuing forest park attributes by giving consideration to the tourist satisfaction. Tour. Econ. 2018, 25, 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Wang, E.; Yu, Y.; Duan, Z. Valuing Recreational Services of the National Forest Parks Using a Tourist Satisfaction Method. Forests 2021, 12, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, G.; Erifo, S.; Addis, G.; Gebre, G.G. Economic valuation of urban forest using contingent valuation method: The case of Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Trees For. People 2023, 12, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Riccia, L.; Assumma, V.; Bottero, M.C.; Dell’Anna, F.; Voghera, A. A Contingent Valuation-Based Method to Valuate Ecosystem Services for a Proactive Planning and Management of Cork Oak Forests in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2023, 15, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Dwyer, L.; Li, G.; Cao, Z. Tourism economics research: A review and assessment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1653–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. On Competition. Updated and Expanded Ed; Harvard Business School Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, J.C.; Bisht, I.S. Reviving Smallholder Hill Farming by Involving Rural Youth in Food System Transformation and Promoting Community-Based Agri-Ecotourism: A Case of Uttarakhand State in North-Western India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbstl, U.; Elands, B.; Wirth, V. Forest recreation and nature tourism in Europe: Context, history, and current situation. In European Forest Recreation and Tourism; Bell, S., Simpson, M., Tyrväinen, L., Sievänen, T., Pröbstl, U., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2009; pp. 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mäntymaa, E.; Tyrväinen, L.; Juutinen, A.; Kurttila, M. Importance of forest landscape quality for companies operating in nature tourism areas. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; He, Z. Research on the Planning and Design of Forest Recreation Base Based on GIS and RMP Analysis—Take the Example of Forest Recreation Base Above the Clouds in Heshun County, Shanxi Province. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 966, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S. Economic linkages and impacts across the talc. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 630–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Jiménez-Caballero, J.L. Nature Tourism on the Colombian—Ecuadorian Amazonian Border: History, Current Situation, and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijs, J.; Heijman, W.; Maris, D.K.; Bryon, J. Criteria for Comparing Economic Impact Models of Tourism. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 1175–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, K.; Fuchs, M.; Lexhagen, M. A multi-period perspective on tourism’s economic contribution—A regional input-output analysis for Sweden. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, K.; Fuchs, M. Aligning tourism’s socio-economic impact with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohmo, T. The economic impact of tourism in Central Finland: A regional input–output study. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parga Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. The Altamira controversy: Assessing the economic impact of a world heritage site for planning and tourism management. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 30, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Meng, S. The economic impacts of the 2018 Winter Olympics. Tour. Econ. 2020, 27, 1303–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Mjelde, J.W.; Kwon, Y.J. Estimating the economic impact of a mega-event on host and neighbouring regions. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E.; Alvelos, H. The Economic Impact of Health Tourism Programmes. In Quantitative Methods in Tourism Economics; Matias, Á., Nijkamp, P., Sarmento, M., Eds.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Klijs, J.; Ormond, M.; Mainil, T.; Peerlings, J.; Heijman, W. A state-level analysis of the economic impacts of medical tourism in Malaysia. Asian-Pac. Econ. Lit. 2016, 30, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Pawlowska, E.; Rodríguez, X.A. The Economic Impact of Academic Tourism in Galicia, Spain. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Robinson, D.; Hite, D. Economic impact of Mississippi and Alabama Gulf Coast tourism on the regional economy. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2017, 145, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artal-Tur, A.; Navarro-Azorín, J.M.; Ramos-Parreño, J.M. Measuring the economic contribution of tourism to destinations within an input-output framework: Some methodological issues. Port. Econ. J. 2020, 19, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerpe, E.E.; Kim, Y.-S. Regional economic impacts of Grand Canyon river runners. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Pan, C.; Pan, J.; Yan, Z.; Ying, Z. The multiplier effect of the development of forest park tourism on employment creation in China. J. Employ. Couns. 2011, 48, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Blair, P.D. Foundations of Input-Output Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leontief, W. Input-Output Economics, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Leung, P. Linkage measures: A revisit and a suggested alternative. Econ. Syst. Res. 2004, 16, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Yoo, S.-H. The role of the capture fisheries and aquaculture sectors in the Korean national economy: An input–output analysis. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.W. Input-output and economic base multipliers: Looking backward and forward. J. Reg. Sci. 1985, 25, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBS. Chinese Input-Output Table 2012; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NBS. Chinese Input-Output Table 2017; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NBS. Chinese Input-Output Table 2018; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T4754-2017; Industrial Classification for National Economic Activities. China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T4754-2011; Industrial Classification for National Economic Activities. China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Li, J.; Li, M. On the calculation of tourism industry and tourist adding value. Tour. Trib. 1999, 5, 16–19+76. [Google Scholar]

- NTA. Tourism Sample Survey Data 2013; China Tourism Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- NTA. Tourism Sample Survey Data 2018; China Tourism Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- NTA. Tourism Sample Survey Data 2019; China Tourism Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SFA. China Forestry Statistics Yearbook 2012; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- SFA. China Forestry Statistics Yearbook 2017; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- SFA. China Forestry Statistics Yearbook 2018; China Forestry Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020-Key Findings; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, S.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q. Changes of China’s forestry and forest products industry over the past 40 years and challenges lying ahead. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 123, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFA. How Was the Third Pillar Industry of Forestry Formed?—Summary of China’s Forest Tourism Development. Available online: http://www.lydcxh.com/h-nd-872.html (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Hara, T. Quantitative Tourism Industry Analysis; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, M.N.H.; Su, Z.; Bhuiyan, A.B.; Rashid, M.; Al-Mamun, A. Economy-wide impact of tourism in Malaysia: An input-output analysis. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liao, X.; Yin, R. Measuring the socioeconomic impacts of China’s Natural Forest Protection Program. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, N. The role of the marine industry in China’s national economy: An input–output analysis. Mar. Policy 2019, 99, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, R.G.; Oh, C.-O. Is tourism a low-income industry? Evidence from three coastal regions. J. Travel Res. 2011, 51, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattarinich, X. Pro-Poor Tourism Initiatives in Developing Countries: Analysis of Secondary Case Studies; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, J.; Munn, I.A.; Henderson, J.E. Economic contributions of wildlife watching recreation expenditures (2006 & 2011) across the U.S. south: An input-output analysis. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 17, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munjal, P. Measuring the economic impact of the tourism industry in India using the Tourism Satellite Account and input—Output analysis. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, S.-M.; Choe, Y.; Song, S.-Y. An estimation of the contribution of the international meeting industry to the Korean national economy based on input—Output analysis. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneally, M.; Jakee, K. Satellite accounts for the tourism industry: Structure, representation and estimates for Ireland. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 971–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S. The economic impact of tourism in SIDS. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Forest Recreation Sub-Sectors | Sectors in ICNTRA | Sectors in I-O Table (2018) |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation(F) | Tourism railway transportation; Tourism road transportation; Tourism water transportation; Tourism air transportation; Passenger ticket agent | Railway passenger transport; Urban public transport and road passenger transport; Water passenger transport; Air passenger transport; Transport agency |

| Accommodation(F) | General tourist accommodation services; Health tourism accommodation services | Accommodation |

| Catering(F) | Tourism dinner services; Tourism fast food services; Tourism beverage services Tourism snack services; Tourism catering delivery services | Catering |

| Retail(F) | Travel tools and fuel shopping; Tourism product shopping | Retail trade |

| Sightseeing(F) | Park Sightseeing; Other forms of sightseeing; | Ecological protection and environmental management; Water management; Forest products and services; Business services |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | Tourism culture and entertainment; Tourism fitness entertainment; Leisure entertainment; Other tourism services (Travel agencies and related services, Tourism financial services, Other comprehensive tourism services) | Culture and art; Sports; Entertainment; Households Services; Health, Postal, Telecommunications, Internet and related services, Monetary and other financial services, Insurance, Leasing; Public management and social organizations |

| Forest Recreation Sub-Industries | Output ($Billion) 1 | Weight | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2017 | 2018 | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Transportation(F) | 39.45 | 101.17 | 117.76 | 0.0456 | 0.2502 | 0.2274 |

| Accommodation(F) | 20.17 | 56.18 | 68.96 | 0.2613 | 0.4469 | 0.4364 |

| Catering(F) | 36.55 | 75.94 | 79.37 | 0.1250 | 0.1734 | 0.1508 |

| Retail(F) | 29.66 | 42.83 | 52.28 | 0.0259 | 0.0483 | 0.0598 |

| Sightseeing(F) | 12.10 | 25.07 | 25.37 | 0.0168 | 0.0196 | 0.0172 |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | 6.26 | 20.59 | 15.07 | 0.0030 | 0.0058 | 0.0034 |

| Total | 144.18 | 321.78 | 358.81 | |||

| Backward Linkage | Forward Linkage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Recreation Sub-Industries | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Transportation(F) | 0.963 | 0.907 | 0.921 | 0.402 | 0.491 | 0.507 |

| Accommodation(F) | 0.898 | 0.919 | 0.947 | 0.379 | 0.456 | 0.468 |

| Catering(F) | 0.881 | 0.988 | 1.009 | 0.377 | 0.428 | 0.435 |

| Retail(F) | 0.624 | 0.670 | 0.698 | 0.378 | 0.411 | 0.428 |

| Sightseeing(F) | 0.996 | 1.010 | 1.038 | 0.366 | 0.406 | 0.416 |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | 0.765 | 0.817 | 0.841 | 0.352 | 0.386 | 0.394 |

| Average | 0.855 | 0.885 | 0.909 | 0.376 | 0.430 | 0.441 |

| Forest Recreation Sub-Industries | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation(F) | 0.753 | 0.749 | 0.770 |

| Accommodation(F) | 0.360 | 0.422 | 0.464 |

| Catering(F) | 0.642 | 0.614 | 0.570 |

| Retail(F) | 0.367 | 0.234 | 0.259 |

| Sightseeing(F) | 0.238 | 0.202 | 0.184 |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | 0.094 | 0.136 | 0.089 |

| Total | 2.454 | 2.357 | 2.336 |

| Forest Recreation Industries | National Economy Industries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest recreation | No. 6 * | No. 1 | No. 30 | No. 35 | No. 33 |

| (0.158) | (0.120) | (0.114) | (0.090) | (0.084) | |

| Transportation(F) | No. 30 | No. 18 | No. 11 | No. 33 | No. 3 |

| (0.059) | (0.037) | (0.035) | (0.034) | (0.026) | |

| Accommodation(F) | No. 6 | No. 34 | No. 12 | No. 35 | No. 1 |

| (0.033) | (0.027) | (0.022) | (0.020) | (0.019) | |

| Catering(F) | No. 6 | No. 1 | No. 29 | No. 12 | No. 30 |

| (0.104) | (0.082) | (0.026) | (0.020) | (0.019) | |

| Retail(F) | No. 35 | No. 34 | No. 30 | No. 33 | No. 12 |

| (0.019) | (0.015) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.004) | |

| Sightseeing(F) | No. 35 | No. 33 | No. 12 | No. 10 | No. 30 |

| (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.007) | |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | No. 12 | No. 35 | No. 33 | No. 32 | No. 34 |

| (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Added Value Multiplier | Employment Multiplier (Unit: Person/$ Million) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Recreation Sub-Industries | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 | 2012 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Transportation(F) | 0.293 | 0.308 | 0.319 | 9.664 | 9.230 | 8.854 |

| Accommodation(F) | 0.144 | 0.177 | 0.196 | 8.168 | 12.383 | 12.295 |

| Catering(F) | 0.266 | 0.256 | 0.242 | 14.159 | 17.055 | 14.452 |

| Retail(F) | 0.157 | 0.102 | 0.114 | 17.612 | 12.417 | 12.566 |

| Sightseeing(F) | 0.090 | 0.082 | 0.074 | 2.695 | 2.829 | 2.435 |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | 0.039 | 0.057 | 0.037 | 1.281 | 1.904 | 1.125 |

| Total | 0.989 | 0.981 | 0.983 | 53.581 | 55.824 | 51.722 |

| Forest Recreation Sub-Industries | Remaining Industries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest recreation | No. 29 | No. 35 | No. 30 | No. 6 | No. 31 |

| (5.678) | (2.548) | (1.191) | (0.973) | (0.973) | |

| Transportation(F) | No. 29 | No. 35 | No. 30 | No. 38 | No. 31 |

| (1.158) | (0.682) | (0.615) | (0.443) | (0.390) | |

| Accommodation(F) | No. 29 | No. 35 | No. 6 | No. 38 | No. 30 |

| (1.191) | (0.562) | (0.205) | (0.172) | (0.132) | |

| Catering(F) | No. 29 | No. 6 | No. 35 | No. 30 | No. 12 |

| (1.979) | (0.642) | (0.351) | (0.199) | (0.126) | |

| Retail(F) | No. 35 | No. 29 | No. 30 | No. 31 | No. 38 |

| (0.549) | (0.291) | (0.132) | (0.099) | (0.066) | |

| Sightseeing(F) | No. 29 | No. 35 | No. 31 | No. 30 | No. 38 |

| (0.457) | (0.285) | (0.172) | (0.079) | (0.066) | |

| Entertainment and other services(F) | No. 29 | No. 35 | No. 31 | No. 38 | No. 12 |

| (0.172) | (0.119) | (0.066) | (0.033) | (0.033) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, Y.; He, D.; Xu, Z.; Shi, X. The Role of the Forest Recreation Industry in China’s National Economy: An Input–Output Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129690

Qiu Y, He D, Xu Z, Shi X. The Role of the Forest Recreation Industry in China’s National Economy: An Input–Output Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129690

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Yingying, Dan He, Zhe Xu, and Xiaoliang Shi. 2023. "The Role of the Forest Recreation Industry in China’s National Economy: An Input–Output Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129690

APA StyleQiu, Y., He, D., Xu, Z., & Shi, X. (2023). The Role of the Forest Recreation Industry in China’s National Economy: An Input–Output Analysis. Sustainability, 15(12), 9690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129690