1. Introduction

Technological advances have facilitated the development of innovative forms of educational practices. Various modes of learning continue to emerge, and learners have been given the flexibility to engage in learning activities to address their individual needs with the aid of digital and mobile technologies [

1]. HyFlex learning is one of these emerging modes of learning. It has been generally conceptualised as a hybrid and flexible mode of learning, which often involves face-to-face classroom and online environments [

2,

3,

4]. Students’ learning experience can be enhanced through flexible participation in online and/or face-to-face learning activities, as well as synchronous communication with peers and teachers at various locations [

5,

6].

HyFlex learning has received increasing attention in both research and practice in the past decade [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic, most educational institutions worldwide had to suspend their face-face-classes and substitute them with HyFlex modes of learning. There has also been a proliferation of research on HyFlex learning and the effective ways to optimise it. For example, Sukiman et al. [

12] explored the effectiveness of HyFlex learning in undergraduate and postgraduate courses for the sake of developing learning patterns. Gnaur et al. [

13] analysed students’ views on how HyFlex learning could be best designed for learning environment, adaptability, and learning outcomes. Kawashaki et al. [

14] developed and implemented a HyFlex learning platform for nursing students and evaluated whether the platform could address the limitations of remote learning. Sumandiyar et al. [

15] investigated whether HyFlex learning was an effective instructional approach during the COVID-19 pandemic. Triyason et al. [

16] created and implemented an online platform to facilitate HyFlex learning and examined the potential problems that might affect its implementation. The findings of these studies would be useful in informing the design and implementation of HyFlex learning.

However, despite the large body of related empirical work, very few review studies have been conducted to provide an overall picture of HyFlex learning as an emerging mode of learning. Relevant review studies have only dealt with HyFlex learning benefits and challenges [

17], HyFlex learning practices in a specific subject discipline [

18], and limitations of HyFlex learning research [

19]. Furthermore, following the widespread practice of HyFlex learning during the COVID-19 pandemic [

20,

21] and the development of educational technologies over the years [

22], the research issues and practices of HyFlex learning have been changing. Reviews of HyFlex learning also need to address its longitudinal development, which has yet to be covered.

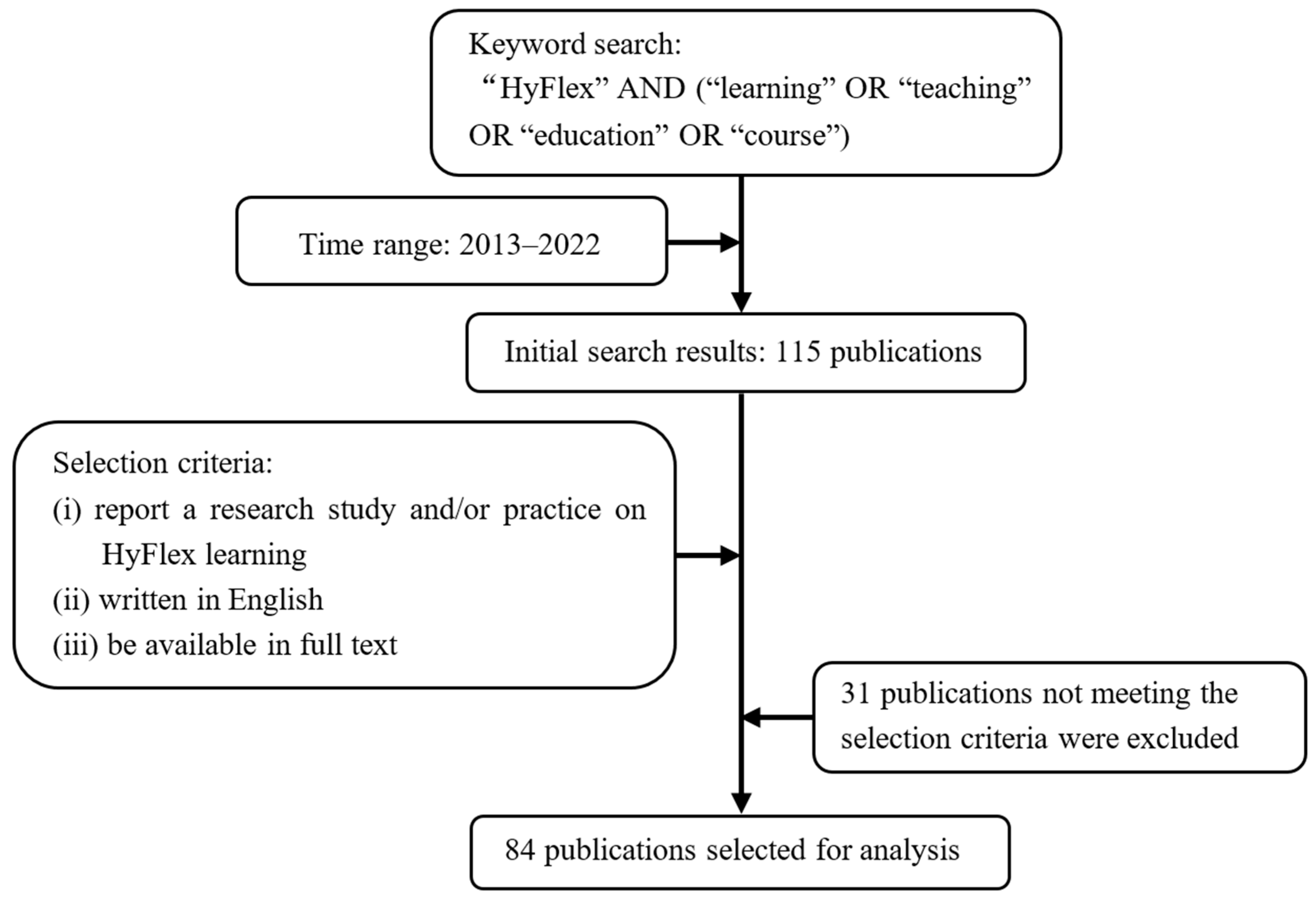

To address the research gap in the literature, this paper presents a systematic review study of HyFlex learning in research and practice over the past decade. Such an investigation is important in not only advancing our understanding of the field, but also providing insights into its sustainable development. This study has focused on the following research questions:

What are the publication patterns of HyFlex learning over the past decade?

What are the changes in research issues of HyFlex learning over the past decade?

How have the practices of HyFlex learning been changed over the past decade?

What are the changes in benefits and challenges of HyFlex learning over the past decade?

5. Discussion

The results of this study present the longitudinal and latest development of HyFlex learning in both research and practice. They supplement other related reviews in this area. For example, when compared with the work of Detienne et al. [

17], which summarised the benefits and challenges of HyFlex learning based on 20 articles, our study systematically surveyed a much larger collection of 84 articles and analysed the longitudinal aspect of HyFlex learning to identify its changes over the years. Furthermore, this study substantially extended our previous preliminary review [

29] on HyFlex learning research by also covering its major practices and recommendations reported in the literature to highlight the directions for sustainable development in this area.

Regarding the publication patterns in this area, the sharp increase in the number of publications in the past three years may be due to a sudden shift in the mode of learning from a traditional face-to-face classroom environment to a HyFlex classroom as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This has drawn much attention in terms of examining the effectiveness of HyFlex learning during the pandemic [

46,

47]. Relevant work has broadly addressed areas such as HyFlex learning design for specific disciplines [

48,

49,

50], as well as the experiences of students and teachers [

40,

51,

52]. The findings of relevant work reveal that HyFlex has served as an effective teaching and learning approach during the pandemic [

40]. However, considering also the challenges as reported in the publications and summarised in this review, future work should examine the extent to which HyFlex learning remains an approach preferred by students and teachers after the pandemic.

Consistent with prior review studies on technology-enhanced education [

53,

54,

55], the findings of this study have revealed a large proportion of research on HyFlex learning at the tertiary level of education. Such a result may be attributed to the flexibility of universities in terms of course design, scheduling, and course delivery [

56]. This facilitates university faculties in designing and implementing HyFlex courses in different disciplines, which has resulted in a wide range of data from those courses for analysing the effectiveness of HyFlex learning.

The findings on subject disciplines can be categorised into what Biglan [

57,

58] refers to as pure–soft (e.g., education), pure–hard (e.g., biology), applied–soft (e.g., geography), and applied–hard (e.g., computer science) disciplines. This diversity implies the cross-disciplinary nature of HyFlex learning as well as the applicability of HyFlex learning in various disciplines. The research issues covered in the HyFlex learning research highlight two key areas of interest among researchers. One concerns the ways to improve student learning outcomes by examining students’ learning experiences and behaviours [

36,

59,

60] and teachers’ and students’ perceptions of HyFlex learning [

61,

62], whereas another pertains to the ways to optimise HyFlex learning by investigating the nature of HyFlex learning, including its features, effectiveness, benefits, and challenges [

44,

63,

64].

Notably, HyFlex learning lays an emphasis on technology use based on the findings of its practices. The ways in which technologies such as livestreaming videos, learning management systems, and chat tools are applied in the practices reveal that they have been used primarily for three main purposes: course delivery, course management, and in-class/off-class communication. The integration of these technologies into practices was observed to bring various benefits to student learning: (i) allowing remote students to have a presence in face-to-face learning by watching livestreaming videos [

65], (ii) improving learning experiences and learning outcomes by having easy access to online instructional resources and content from their teachers [

63], (iii) increasing engagement and interaction by making use of the chat function of online class platforms [

39], and (iv) improving teachers’ and students’ perceptions of HyFlex learning [

41,

62].

Concerning the recommendations given in the publications, the roles of teachers and institutions are shown to play a major role in the success of HyFlex learning. Teachers’ adaptation of pedagogies and upgrading of digital skills for HyFlex learning are emphasised in the publications. These pedagogies and digital skills focus on enhancing student engagement and interaction. Examples include using structured discussions that provide equal opportunities to all participants in course discussions [

44], controlling access to streaming options (e.g., recorded videos) for students not meeting the class participation criterion [

45], using real-time communication tools [

42], and using the number of times that students watch class videos and the number of questions that they answer in an online discussion forum as their attendance criterion [

66].

Regarding the role of institutions, institutional support for HyFlex learning is highlighted in the publications as a factor contributing to the effectiveness of HyFlex learning. It is shown that the support often occurs in two types. One is administrative and technical support, such as offering credits for attending online classes [

42], providing appropriate facilities and equipment for HyFlex learning [

42], hiring a teaching assistant to monitor online chat content, and answering questions related to HyFlex courses [

38]. Another type is teacher-training support such as professional courses for training teachers to become familiar with the hardware equipment and software systems for delivering HyFlex courses. The finding echoes the observations of Lakhal and Meyer [

67], who emphasise the importance of support for teachers since successful HyFlex learning requires close alignment of institutional and teacher objectives.

6. Conclusions

This paper reports a longitudinal study of HyFlex learning, which contributes to comprehensively revealing its publication patterns, research issues, features of practices, benefits, and challenges, as well as recommendations given in the publications over the past decade. The findings provide evidence showing HyFlex learning as an area of interest among researchers with an increasing number of studies. While HyFlex learning has been mainly studied at the tertiary education level, more research could be done on it at secondary and primary education levels. Furthermore, most of the previous studies have focused on teachers’ and students’ experiences and behaviours as well as their perceptions of HyFlex learning. As such, further studies could examine other aspects which have been relatively less explored such as the effective practices of HyFlex learning in subject disciplines of various natures.

The findings of this study have shown that technology-mediated practices in HyFlex learning are in close relation to course delivery, course management, and in-class/off-class communication. They would help teachers to make informed decisions on the ways in which technologies could be used to support HyFlex learning practices, selection of suitable technologies that meet their teaching needs, and strategic planning of their teaching methods. Additionally, the findings have summarised the recommendations for HyFlex learning and could serve as a reference for institutions and teachers to enhance the effectiveness of HyFlex learning.

This study is limited by the publications examined, which were published mostly in the past three years during the COVID-19 pandemic. This special context in which HyFlex learning was implemented may limit the generalisability of the findings of the study. Future research should cover relevant work carried out after education delivery has returned to normal to examine the post-COVID-19 development of HyFlex learning. Moreover, future research could analyse the relations between HyFlex learning and related types of learning approaches such as flipped learning and blended learning in order to identify the similarities and differences between them and further developments of HyFlex learning.