Cross-Regional Allocation of Human Capital and Sustainable Development of China’s Regional Economy—Based on the Perspective of Population Mobility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

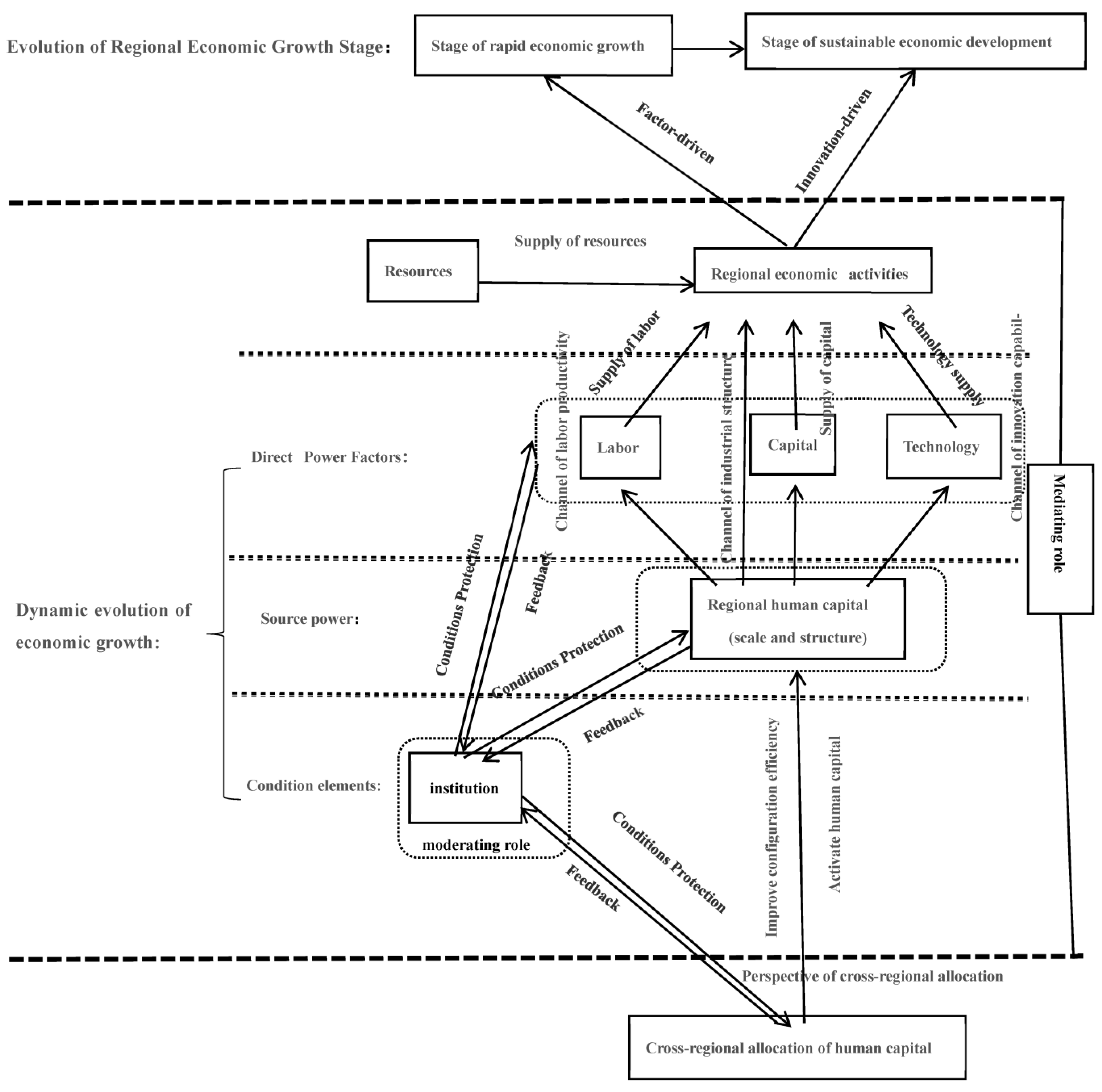

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Direct Effect

2.2. The Mediating Effects

- The mediating effect of labor productivity

- 2.

- The mediating effect of industrial structure

- 3.

- The mediating effect of regional innovation capacity

2.3. The Moderating Effect

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Setting

3.2. Variable Selection

- Dependent variable

- 2.

- Core independent variables

- (1)

- As the carrier of human capital, the flow of the labor force will inevitably lead to human capital flow, which is itself the re-allocation of human capital.

- (2)

- Referring to the existing literature, we chose the net inflow rate of the labor force as a measure of human capital cross-regional allocation. For example, reference [40] in our study used the net inflow rate of the labor force as a measure of human capital cross-regional allocation to study enterprise productivity.

- (3)

- Based on the reality of China’s population mobility, at present, the years of education of floating population in China exceed the average level of education, which means the human capital contained in the floating population is higher.

- 3.

- Control variables

- 4.

- Mediating variables

- 5.

- Moderating variable

3.3. Descriptive Statistics of Data Sources and Variables

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Regression

4.2. Endogenous Test

4.3. Robustness Test

- Change the core independent variable

- 2.

- Change the dependent variable

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

- Heterogeneity test based on population size

- 2.

- Heterogeneity test based on level of development

- 3.

- The heterogeneity test based on different administrative status

4.5. Test of Mediating Effect

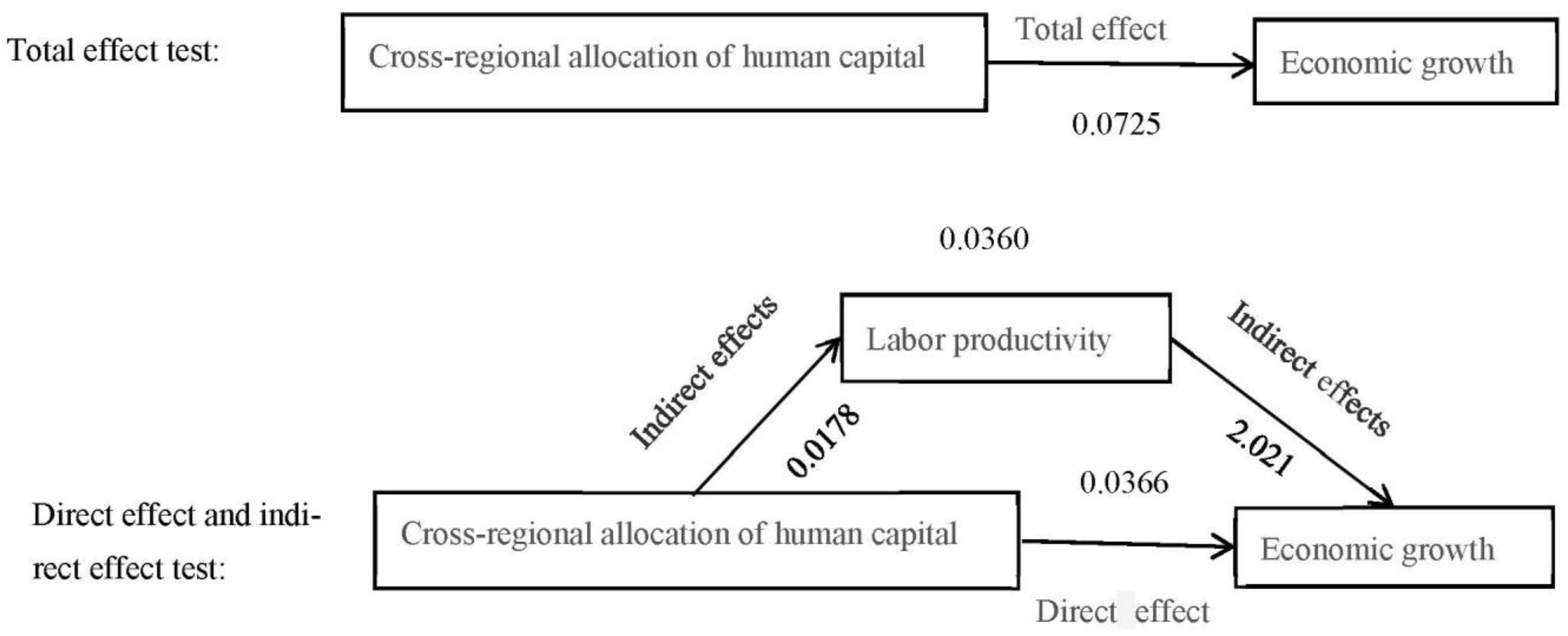

- The mediating effect test of labor productivity

- 2.

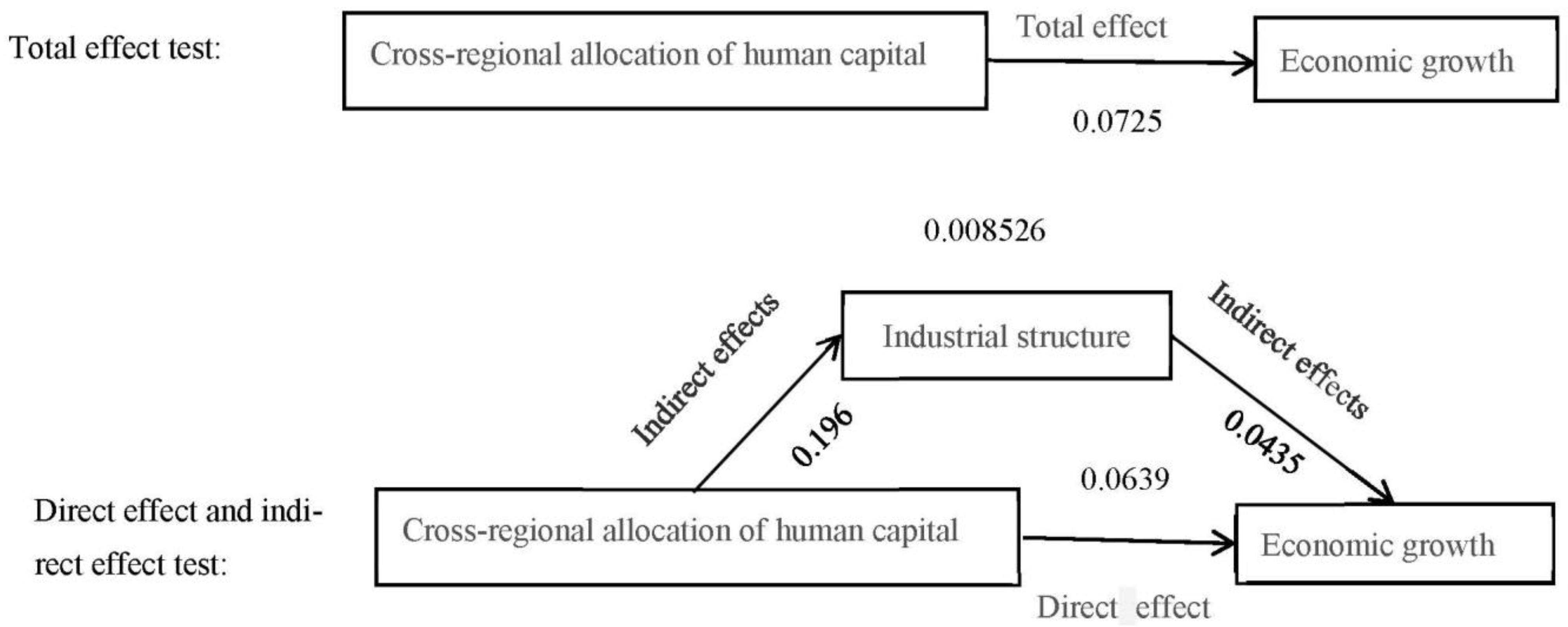

- The mediating effect test of industrial structure

- 3.

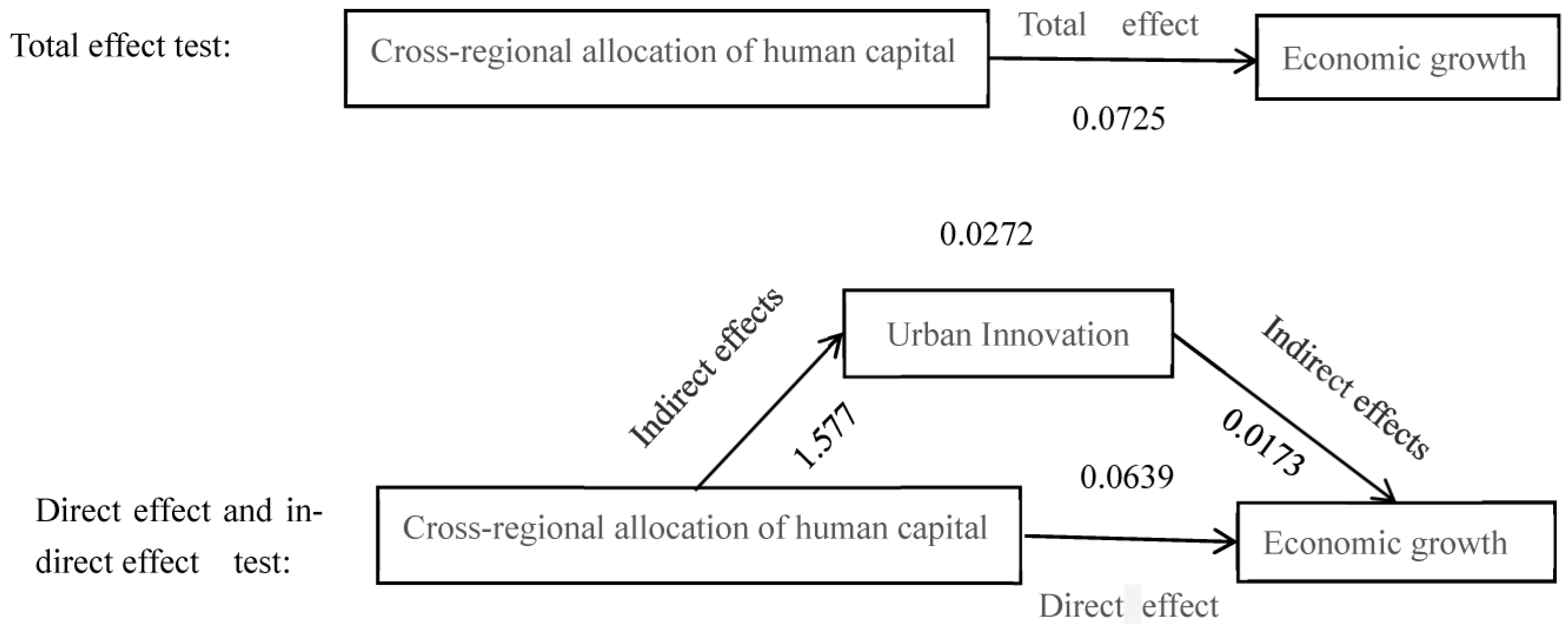

- The mediating effect test of regional innovation capability

4.6. The Moderating Effect Test of Household Registration Policy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Recommendations

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Economic Growth Frontier Research Group; Yuan, F.H.; Chen, C.P.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, M.T. China’s long-term economic growth path, efficiency and potential growth level. Econ. Res. 2012, 11, 4–17+75. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J. Does China’s “Structural acceleration” to “Structural deceleration” originate from industrial structure? A study based on a stochastic frontier model. J. Southeast Univ. 2018, 5, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B. From the Chinese growth miracle to high-quality growth. Political Econ. Rev. 2022, 6, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F. “Structural acceleration” and “Structural deceleration” of long-term growth processes: An explanation. Econ. Res. 2012, 3, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S. Research on the Characteristics of Time and Space Conversion of China’s Economy from High-speed Growth to High-quality Development. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2019, 36, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.Z.; Kim, H.H. An empirical study on the high-quality development efficiency of the urban economy in China. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2022, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Z. Promote the transformation of the driving forces for China’s economic growth and achieve high-quality economic development. Ind. Inf. Technol. 2022, 4, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, P.Y. China’s productivity dilemma for economic growth: A slowdown in growth with increased investment. World Econ. 2016, 1, 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.B.; Jiang, Q.B. Population size, population ageing and economic growth. Popul. J. 2023, 2, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Fink, G. Implications of population ageing for economic growth. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2010, 4, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arrow, K.J. The economic implications of learning by doing. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1971, 3, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- The China Economic Growth Frontier Research Group; Yuan, F.H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.M.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, M.T.; Zhang, L. The low efficiency impact and deceleration of China’s economic growth. Econ. Res. 2014, 12, 4–17, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.B.; Zhu, H.; Kang, J.J.; Song, S.F. Research on the growth effect of intellectual property protection system in the transition period. Econ. Res. 2012, 8, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Tian, M.; Qin, G. Coupling, coordination and optimization of new urbanization and industrial structure upgrading. East China Econ. Manag. 2020, 3, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.L. Analysis of China’s economic growth dynamics under The New Normal. Soc. Sci. Chin. Univ. 2017, 6, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.Y.; Wan, G.; Morgan, P.J. Prospects for a re-acceleration of economic growth in the PRC. J. Comp. Econ. 2016, 44, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.P.; Yang, Z. Research on the driving mechanism of innovation-driven economic growth and its realization path. Reform Econ. Syst. 2016, 6, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Laeven, L.; Levine, R.; Michalopoulos, S. Financial innovation and endogenous growth. J. Financ. Intermediat. 2015, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H. Study on the Path of Economic Growth in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Central Party School of the Communist Party of China, Beijing, China, November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xia, H. Human capital allocation efficiency in China’s inter-provincial economic growth. Popul. Econ. 2013, 6, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Benhabib, J.; Spiegel, M.M. The role of human capital in economic development evidence from aggregate cross-country data. J. Monetary Econ. 1994, 34, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nan, Y.; Liu, X. China’s economic growth problem: Human capital misallocation and its solution. Econ. Res. 2017, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, C. Upgrading the human capital structure and economic growth—Also on the formation and narrowing of the Midwestern Sectional Figure Skating Championships gap. Econ. Res. 2018, 3, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.G.; Liu, W.T.; Peng, X.Y. Spatial differentiation of population migration and economic development: A human capital accumulation perspective. Chin. Soft Sci. 2023, 1, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. A Study on Regional Human Capital Allocation and Its Impact on Economic Growth in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Liaoning University, Shenyang, China, June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, P. Analysis and Forecast of China’s Economic Situation in 2015; Social Sciences Literature Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. A new round of power transformation and route choice of China’s economy. Manag. World 2017, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, Y. The gap of human capital toward high-quality development in China: From the perspective of human capital structure and allocative efficiency. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2020, 4, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, K. Allocation of R&D human capital and technological innovation: Perspective of heterogeneous education level. Sci. Prog. Countermeas. 2021, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.H.; Li, L.T. Study on the interaction mechanism between human capital and rural economy based on the theory of economic growth dynamics. China Agric. Sci. Technol. News 2006, 4, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Masatoshi, K.; Hiroyuki, O.; Yuji, H. Does founders’ human capital matter for innovation? Evidence from Japanese Start-ups. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 1, 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.A.C.; Queiros, A.S.S. Economic growth, human capital and structural change: A dynamic panel data analysis. J. Res. Policy 2016, 8, 1636–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadan, J. Estimating the effects of human capital constraints on innovation in the caribbean. Economies 2018, 2, 6–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, S.M. Economic Growth; He, H.X., Translator; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mankiw, N.G.; David Romer David, N.W. A contribution to the empiric of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 2, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H. Research on the influence of human capital structure and R&D investment on economic growth. Chin. Prices 2022, 12, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Lee, J.; Huang, S. Migration, demographic dividend and economic growth. East China Econ. Manag. 2022, 14, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.C. Empirical analysis of population mobility and regional economic development. Mark. Hum. Anal. 2004, 5, 23–26, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Lin, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z. A study on the interaction between population mobility and economic growth. Soc. Sci. Abstr. 2016, 2, 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Liang, Q.X. Labor mobility, across-regional allocation of human capital and enterprise productivity. Labor Econ. Res. 2022, 5, 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y. A study on the spatial structure of trans-regional migration flows in China—Description, model expression and prediction. Popul. Econ. 2022, 6, 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X. Research on the Relationship between Inter-Provincial Population Migration and Regional Economic Development in China from a Spatial Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, Shanghai, China, November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Docquier, F.; Rapoport, H. Globalization, Brain Drain and Development; Working Paper, No. 2011-18; Bar-Ilan University, Department of Economics: Ramat-Gan, Israel, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M. Geographical distance and technology spillover effects—A spatial econometric interpretation of technology and economic agglomeration. Economics 2009, 4, 1549–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L.; Qiao, X. Population migration cost, city size and productivity in our country. Economics 2020, 1, 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.; Bie, Z. FDI, human capital accumulation and economic growth. Econ. Res. 2006, 4, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y. A Study on the Impact of Heterogeneous Human Capital on Industrial Structure Upgrading—Inner Mongolia as an Example. Ph.D. Thesis, Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing, China, November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. Foreign human capital, cultural diversity and urban innovation in China. Econ. Res. 2019, 11, 172–192. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Si, S.; Li, J. Research on the effect of regional talent allocation on high-quality economic development—Based on the perspective of innovation-driven growth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Human capital flow and technology spillover effects: An empirical study based on the data of Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Econ. Sci. 2008, 4, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Cai, F. The course and prospect of the reform of household registration system. Guangdong Soc. Sci. 2008, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, T.; Wu, K. Human capital mobility and innovation: A comparative study based on China’s talent introduction policy. J. Shanghai Univ. 2018, 4, 124–140. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Gao, X. Urbanization, digital economy and high-quality economic development—An empirical analysis based on intermediary effect and regulatory effect. Econ. Perspect. 2021, 3, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Nowakowska-Grunt, J.; Gorbanyov, V.; Egorova, M. Green technology and sustainable development: Assessment and green growth frameworks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.P.; Li, X.C.; Chen, Q. The effect of floating population on urban entrepreneurial activity: Mechanism and evidence. Econ. Res. 2018, 6, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Lu, M. The footprint of urban human capital across the century—historical heritage, policy impact and labor mobility. Econ. Res. 2019, 1, 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wan, G. Does China’s rural infrastructure promote inclusive growth? Econ. Res. 2016, 10, 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Li, J.; Fang, X.; Wei, H. The mechanism and effectiveness test of digital Pratt & Whitney Finance for Inclusive Growth. Stat. Study 2021, 10, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, S.; Bloom, N.; Card, D.; Van Reenen, J.; Wolter, S. Management practices, workforce selection, and productivity. J. Labor Econ. 2018, 1, S371–S409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, F.; Nan, T.; Wang, X. Causes and Evolution Characteristics of Green Innovation Efficiency Loss: The Perspective of Factor Mismatch under Local Government Competition. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, K.; Shi, F. Does regional innovation environment have an impact on the gathering of technological talent? An empirical study based on 31 provinces in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Chen, X. Migration and urban innovation: Evidence from vice-provincial cities and above in China. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 11, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, G.; Melanie, M. The aggregate productivity effects of internal migration: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Political Econ. 2019, 5, 2229–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faggian, A.; Isha, R.; Kathryn, D. The Inter-regional migration of human capital and its regional consequences: A review. Reg. Stud. J. Reg. Stud. Assoc. 2017, 1, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Y.; Liu, Z.Y. An analysis of the impact of different types of human capital on economic growth. Popul. Econ. 2004, 2, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.J.; Dong, Y.F. Heterogeneous human capital flow and regional economic development: A case study of Shanghai. China Popul. Sci. 2007, 4, 50–57, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.H. The global dimension of China’s talent competition. Chin. Talent 2018, 7, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, M.; Liao, G.M.; Yu, X.Y. The brain gain of corporate boards: Evidence from China. J. Financ. 2015, 4, 1629–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunerhjelm, P.; Ding, D.; Per, T. Labour market mobility, knowledge diffusion and innovation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 123, 103386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.G. The impact of human capital flow on regional economic growth disparities. J. Natl. Sun Yat-Sen Univ. Sci. 2009, 5, 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Q. A Study on the Effect of Labor Mobility on Regional Economic Growth. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M. Study on the Relationship between Human Capital and Economic Growth Considering Population Mobility. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University of Finance and Economics, Tianjin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.Y.; Huang, J.Z.; Zhuang, H.M. Flow of human capital, agglomeration of high-tech industries and economic growth. Nankai Econ. Res. 2020, 6, 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.Y.; Wang, M.R. Seven measures of “Talent competition” in China’s big cities. Policy Outlook 2018, 7, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti, V.; Cristina, C.; Elena, V. Migration of skilled workers and innovation: A European perspective. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 2, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S.; Rebecca, D.; Timothy, M.; Beatriz, P. The Contribution of High-Skilled Immigrants to Innovation in the United States; Standford Graduate School of Business Working Paper; No. 3748; Stanford Graduate School of Business: Stanford, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kangasniemi, M.; Matilde, M.; Catherine, R.; Lorenzo, S. The economic impact of migration: Productivity analysis for Spain and the UK. J. Product. Anal. 2012, 3, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krugman, P. The myth of Asia’s miracle. Foreign Aff. 1994, 6, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maré, D.; Richard, F. Productivity and Local Workforce Composition. In Geography, Institutions and Regional Economic Performance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, T.R. The quality vs the quantity of schooling: What drives economic growth? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2011, 4, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peri, G. The effect of immigration on productivity: Evidence from US States. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2012, 1, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, W.D. The Effect of Dynamic Machining between Human Capital and Industrial Structure Transformation. Econ. Rev. 2010, 6, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.W.; Yang, J.R. A empirical study of the relation of industrial structure upgrading and human capital:a example for Jiang Xi province. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2007, 12, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.R.; Li, P. The Interaction Relation between Human Capital and Industrial Structure in Guang Dong. Hum. Resour. Dev. China 2009, 3, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, M.S.; Mao, Z.B. The mechanism analysis of human capital to economic growth. J. Chong Qing Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2008, 1, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Hou, Y.L. Government training subsidy, externality of enterprise training and technological innovation: From the perspective of human capital investment in incomplete labor market. Econ. Manag. Res. 2019, 4, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, J.B. Human capital and world technology frontier. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2014, 4, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, C.; Badulescu, A. Education and human capital as engines for economic growth: A literature review. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2015, 2, 665–673. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Hu, J.X. Evaluation of the coupling relationship between China’s regional scientific and technological innovation and high-quality economic development. Sci. Technol. Prog. Countermeas. 2019, 8, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.B.; Cui, Y.C.; Tsai, S.B.; Wang, D.M. The impact of technical-nontechnical factors synergy on innovation performance: The moderating effect of talent flow. Sustainability 2018, 10, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerr, S.; William, K. Immigration policy levers for US innovation and startups. In Innovation and Public Policy; Goolsbee, A., Jones, B., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022; pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.R.; Chakraborty, B. Human capital accumulation and endogenous growth in a dual economy. Hitotsubashi J. Econ. 2006, 2, 169–195. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R.J. Human capital and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 2, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennaioli, N.; La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. Human capital and regional development. Q. J. Econ. 2013, 1, 105–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunde, U.; Vischer, T. Human capital and growth: Specification matters. Economica 2015, 326, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Li, S.R. Industrial structure and economic growth. China’s Ind. Econ. 2002, 5, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, C.R.; Glaeser, E.L. The divergence of human capital levels across cities. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2005, 3, 407–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oreski, D.; Marsic, K.; Kedmenec, I. The association between human capital and overall productivity in the European Union countries. CECIIS 2015, 2, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J.M. Smart cities: Quality of life, productivity, and the growth effects of human capital. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 2, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, A.; Papaioannou, E. Human capital, the structure of production, and growth. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2009, 1, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviotti, P.; Pyka, A. From necessities to imaginary worlds: Structural change, product quality and economic development. Technol. Forecasting Soc. Change 2013, 80, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhvlediani, T.; Cieslik, A. Human capital, technological progress and technology diffusion across Europe: Education matters. Empirica. 2020, 3, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, W. On innovative impetus driving China’s sustainable economic growth. Innov. Comput. Inf. 2011, 5, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.B.; Liu, Y.Z.; Yang, Z.W. Spatial-Temporal Evolution and Knowledge Spillovers of Urban Innovation in China. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Category | Variable Name | Symbols | Methods of Calculation and References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Growth rate of GDP per capita | Rjgdp | (Real GDP per capita this year-Real GDP per capita last year)/Real GDP per capita this year | |

| Core independent variables | Net inflow of population | Netinmig | (The inflow of population–the outflow of population)/Total population | |

| Net inflow of advanced human capital | Gjrlzb | (The inflow of college and above population–the outflow of college and above population)/Total population | ||

| Net inflow of ordinary human capital | Ptrlzb | (The inflow of college and below population—he outflow of college and below population)/Total population | ||

| Robustness test variables | Alternative variables to the core independent variables | Netin1 | 1-Registered population/Resident population [55] | |

| Humanc | The inflow of college and above population in one city/the inflow of college and above population in one country [56] | |||

| Alternative variables to the dependent variable | Gdpr | GDP growth rate | ||

| Control variables | Resource Endowment | The land area of the administrative region | Xztdmj | The data came directly from the statistical yearbook |

| Total amount of water resources | Szy | The same asthe above | ||

| Government policy | Fiscal expenditure | Czzc | The same as the above | |

| Public Welfare | Number of ordinary secondary schools | Ptzx | The same as the above | |

| Number of ordinary primary schools | Ptxx | The same as the above | ||

| Number of medical and health institutions | Ylws | The same as the above | ||

| Total stock of public libraries | Ggts | The same as the above | ||

| Openness | The actual amount of foreign capital used | Sjsywz | The same as the above | |

| Net exports | Jck | Export–Import | ||

| Physical capital | Investment in fixed assets | Gdzc | The data came directly from the statistical yearbook | |

| Mediating variable | Labor productivity | Ldscl | Urban GDP/Employed persons in urban units [59] | |

| Industrial structure | Cyjg | Added value of tertiary industry/Added value of secondary industry [14] | ||

| Regional innovation capability | Cxnl | Number of patents granted [62] | ||

| Moderating variable | Household registration control policy | Hjzd | Resident population/Registered population [37] | |

| Variable Symbol | Variable Meaning | Sample Size | Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Rjgdp | Growth rate of GDP per capita | 4544 | 0.421 | 0.325 | 0.001 | 4.677 |

| Core independent variables | Netinmig | The rate of population net inflow | 4544 | −0.026 | 0.108 | 0.348 | 0.760 |

| Rklr | The rate of population inflow | 4544 | 0.039 | 0.080 | 0.000 | 0.762 | |

| Rklc | The rate of population outflow | 4544 | 0.065 | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0.367 | |

| Gjrlzb | Net inflow of advanced human capital | 4544 | 0.040 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Ptrlzb | Net inflow of ordinary human capital | 4544 | −0.065 | 0.212 | −1.246 | 1.000 | |

| Robustness test variables | Gdpr | GDP growth index | 4544 | 0.110 | 0.094 | −0.311 | 3.842 |

| Netin | Alternative indicator of net population inflow rate 1 | 4544 | 0.645 | 0.239 | −2.181 | 0.996 | |

| Humanc | Alternative indicator of net population inflow rate 2 | 4544 | −2.378 | 1.345 | −4.605 | 2.867 | |

| Mediating variable | Ldscl | Labor productivity | 4544 | 0.082 | 0.057 | 0.000 | 0.641 |

| Cyjg | Industrial structure | 4544 | 0.950 | 0.544 | 0.094 | 9.482 | |

| Cxnl | Regional innovation capability | 4544 | 143.796 | 1344.409 | 0.000 | 46,988 | |

| Moderating variable | Hjzd | Household registration control policy | 4544 | 4.431 | 4.970 | 0.314 | 236.136 |

| Control variables | (Resource Endowment) | ||||||

| Xztdmj | The land area of administrative region | 4544 | 16.527 | 21.783 | 1.113 | 261.570 | |

| Szy | Total amount of water resources | 4544 | 1.619 | 3.152 | 0.015 | 34.948 | |

| (Government policy) | |||||||

| Czzc | Public Expenditure | 4544 | 278.949 | 521.857 | 4.930 | 8351.54 | |

| (Public Services) | |||||||

| Ptzx | Number of ordinary secondary schools | 4544 | 86.907 | 126.455 | 5.000 | 2639.00 | |

| Ptxx | Number of ordinary primary schools | 4544 | 172.216 | 181.256 | 6.000 | 1978.00 | |

| Ylws | Number of medical and health institutions | 4544 | 67.856 | 114.509 | 4.134 | 6421.72 | |

| Ggts | Total stock of public libraries | 4544 | 2.145 | 6.736 | 0.003 | 179.850 | |

| (Openness) | |||||||

| Sjsywz | The actual used foreign capital | 4544 | 7.655 | 18.838 | 0.000 | 308.256 | |

| Jck | Net export | 4544 | 12.310 | 189.894 | −3037.5 | 5919.90 | |

| (Physical capital) | |||||||

| Gdzc | Investment in fixed assets | 4544 | 77.789 | 128.506 | 0.003 | 1724.58 | |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netinmig | 0.617 *** (0.215) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 14.40 *** (1.699) | —— | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | 0.133 (0.244) | —— | —— |

| Rklr | —— | —— | —— | 2.054 *** (0.490) | —— |

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.235 (0.221) |

| Xztdmj | 0.0502 (0.312) | 0.654 *** (0.203) | 0.805 (3.023) | −0.0396 (3.021) | 0.871 (3.002) |

| Szy | 1.73 (1.502) | −0.608 (1.200) | 0.203 (0.150) | 0.0112 (0.016) | 0.0208 (0.015) |

| Czzc | 2.91 *** (0.000) | 9.80 * (0.000) | 2.91 *** (0.000) | 0.279 *** (0.000) | 0.288 *** (0.000) |

| Ptzx | 0.751 *** (0.000) | 0.512 *** (0.000) | 0.732 *** (0.000) | 0.721 *** (0.000) | 0.717 *** (0.000) |

| Ptxx | −0.366 *** (0.000) | −0.248 *** (0.000) | −0.354 *** (0.000) | −0.351 *** (0.000) | −0.345 *** (0.000) |

| Ylws | 0.200 ** (0.000) | 0.189 *** (0.000) | 0.185 * (0.000) | 0.212 ** (0.000) | 0.179 * (0.000) |

| Ggts | 0.353 (0.312) | 0.621 (1.012) | 0.341 (0.300) | 0.00375 (0.003) | 0.00336 (0.003) |

| Sjsywz | −0.119 (0.103) | −0.242 (1.012) | −0.104 (1.155) | −0.145 (0.102) | −0.964 (1.311) |

| Jck | 0.120 ** (0.000) | 0.840 ** (0.000) | 0.118 ** (0.000) | 0.116 *** (0.000) | 0.117 ** (0.000) |

| Gdzc | 0.139 *** (0.000) | 0.982 *** (0.000) | 0.140 *** (0.000) | 0.134 *** (0.000) | 0.140 *** (0.000) |

| _cons | 0.329 *** (0.040) | 0.194 *** (0.037) | 0.312 *** (0.039) | 0.247 *** (0.045) | 0.292 *** (0.039) |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.461 | 0.558 | 0.456 | 0.478 | 0.456 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netinmig(-1) | 0.552 *** (0.195) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb(-1) | —— | 13.35 *** (1.611) | —— | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb(-1) | —— | —— | 0.106 (0.218) | —— | —— |

| Rklr(-1) | —— | —— | —— | 1.976 *** (0.453) | —— |

| Rklc(-1) | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.307 (0.204) |

| Xztdmj | 0.0421 (0.003) | 0.575 ** (0.002) | 0.574 (3.023) | −0.0896 (3.021) | 0.998 (3.001) |

| Czzc | 2.66 *** (0.000) | 9.35 *** (0.000) | 2.68 *** (0.000) | 0.252 *** (0.000) | 0.265 *** (0.000) |

| Szy | 0.222 (0.014) | 0.909 (0.010) | 0.257 * (0.140) | 0.0147 (0.015) | 0.0264 (0.014) |

| Ptzx | 0.690 *** (0.000) | 0.447 *** (0.000) | 0.669 *** (0.000) | 0.666 *** (0.000) | 0.650 *** (0.000) |

| Ptxx | −0.325 *** (0.000) | −0.197 *** (0.000) | −0.313 *** (0.000) | −0.316 *** (0.000) | −0.303 *** (0.000) |

| Ylws | 0.301 ** (0.000) | 0.227 *** (0.000) | 0.288 * (0.000) | 0.301 ** (0.000) | 0.279 * (0.000) |

| Ggts | 0.318 (0.312) | 0.153 (1.012) | 0.308 (0.300) | 0.335 (0.355) | 0.279 (0.314) |

| Sjsywz | −0.743 (0.103) | −0.018 (1.012) | −0.636 (1.155) | −0.894 (0.102) | −0.951 (1.311) |

| Jck | 0.960 *** (0.000) | 0.709 *** (0.000) | 0.963 *** (0.000) | 0.894 *** (0.000) | 0.951 *** (0.000) |

| Gdzc | 0.133 *** (0.000) | 0.971 *** (0.000) | 0.135 *** (0.000) | 0.128 *** (0.000) | 0.134 *** (0.000) |

| _cons | 0.342 *** (0.038) | 0.219 *** (0.041) | 0.324 *** (0.037) | 0.268 *** (0.042) | 0.299 *** (0.037) |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.441 | 0.533 | 0.437 | 0.460 | 0.437 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netin | 0.198 *** (0.055) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 14.40 *** (1.699) | —— | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | 0.133 (0.244) | —— | —— |

| Rklr | —— | —— | —— | 2.054 *** (0.490) | —— |

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.235 (0.221) |

| Xztdmj | 0.0348 (2.003) | 0.470 ** (0.202) | −0.138 (2.023) | −0.644 (2.021) | 0.0499 (2.001) |

| Czzc | 0.194 *** (0.000) | 0.606 *** (0.000) | 0.196 *** (0.000) | 0.199 *** (0.000) | 0.192 *** (0.000) |

| Szy | 0.120 (0.140) | 0.235 ** (0.121) | 0.113 * (0.140) | 0.0166 (0.014) | 0.0108 (0.013) |

| Ptzx | 0.690 *** (0.000) | 0.447 *** (0.000) | 0.669 *** (0.000) | 0.666 *** (0.000) | 0.650 *** (0.000) |

| Ptxx | −0.141 *** (0.000) | −0.388 (0.000) | −0.130 *** (0.000) | −0.901 (0.000) | −0.136 *** (0.000) |

| Ylws | 0.301 ** (0.000) | 0.227 *** (0.000) | 0.288 * (0.000) | 0.301 ** (0.000) | 0.279 * (0.000) |

| Ggts | 0.318 (0.312) | 0.153 (1.012) | 0.308 (0.300) | 0.335 (0.355) | 0.279 (0.314) |

| Sjsywz | −0.743 (0.103) | −0.018 (1.012) | −0.636 (1.155) | −0.894 (0.102) | −0.951 (1.311) |

| Jck | 0.960 *** (0.000) | 0.709 *** (0.000) | 0.963 *** (0.000) | 0.894 *** (0.000) | 0.951 *** (0.000) |

| Gdzc | 0.133 *** (0.000) | 0.971 *** (0.000) | 0.135 *** (0.000) | 0.128 *** (0.000) | 0.134 *** (0.000) |

| _cons | 0.342 *** (0.038) | 0.219 *** (0.041) | 0.324 *** (0.037) | 0.268 *** (0.042) | 0.299 *** (0.037) |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.462 | 0.558 | 0.456 | 0.478 | 0.456 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanc | 0.0699 *** (0.008) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 0.0631 *** (0.012) | —— | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | 0.0750 *** (0.011) | —— | —— |

| Rklr | —— | —— | —— | 1.662 *** (0.526) | —— |

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.213 (0.186) |

| _cons | 0.462 *** (0.041) | 0.317 *** (0.042) | 0.319 *** (0.042) | 0.260 *** (0.047) | 0.304 *** (0.042) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.523 | 0.488 | 0.489 | 0.499 | 0.486 |

| (1) Gdpr | (2) Gdpr | (3) Gdpr | (4) Gdpr | (5) Gdpr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netinmig | 0.377 ** (0.147) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 0.326 *** (0.077) | —— | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | 0.310 *** (0.074) | —— | —— |

| Rklr | —— | —— | —— | 0.236 (0.689) | —— |

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | 0.427 (0.487) | |

| _cons | 0.462 *** (0.041) | 0.317 *** (0.042) | 0.319 *** (0.042) | 0.260 *** (0.047) | 0.304 *** (0.042) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.523 | 0.488 | 0.489 | 0.499 | 0.486 |

| Resident Population ≤ 3,720,000 | Resident Population > 3,720,000 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | (6) Rjgdp | |

| Netinmig | 1.360 *** (0.338) | —— | —— | 0.149 (0.202) | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 7.115 *** (1.605) | —— | —— | 12.72 *** (2.760) | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | 1.131 *** (0.297) | —— | —— | −0.398 (0.247) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 2270 | 2270 | 2270 | 2272 | 2272 | 2272 |

| r2 | 0.577 | 0.579 | 0.570 | 0.618 | 0.677 | 0.621 |

| Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | (6) Rjgdp | (7) Rjgdp | (8) Rjgdp | (9) Rjgdp | (10) Rjgdp | (11) Rjgdp | (12) Rjgdp | |

| Netinmig | 0.428 (0.371) | —— | —— | —— | 0.841 *** (0.283) | —— | —— | —— | 0.785 *** (0.294) | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 12.56 *** (2.335) | —— | —— | —— | 11.11 *** (1.537) | —— | —— | —— | 16.93 *** (2.393) | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | −0.0603 (0.432) | —— | —— | —— | 0.636 *** (0.223) | —— | —— | —— | 0.0128 (0.345) | —— |

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | 0.466 (0.452) | —— | —— | —— | −0.325 * (0.190) | —— | —— | —— | 0.678 (0.454) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 1600 | 1600 | 1600 | 1600 | 1742 | 1742 | 1742 | 1742 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| r2 | 0.469 | 0.531 | 0.467 | 0.467 | 0.634 | 0.667 | 0.628 | 0.622 | 0.406 | 0.642 | 0.394 | 0.401 |

| Municipalities Directly under the Central Government or Provincial Capitals | Other Cities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | (6) Rjgdp | (7) Rjgdp | (8) Rjgdp | (9) Rjgdp | (10) Rjgdp | |

| Netinmig | 0.773 * (0.451) | —— | —— | —— | —— | 1.029 *** (0.220) | —— | —— | —— | |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 11.72 *** (1.790) | —— | —— | —— | —— | 11.86 *** (1.383) | —— | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | −0.271 (0.550) | —— | —— | —— | —— | 0.749 *** (0.194) | —— | —— |

| Rklr | —— | —— | —— | 1.813 *** (0.507) | —— | —— | —— | —— | 2.625 *** (0.753) | —— |

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | —— | 2.981 ** (1.271) | —— | —— | —— | —— | −0.295 ** (0.139) |

| Control varibles | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 496 | 496 | 496 | 496 | 496 | 4062 | 4062 | 4062 | 4062 | 4062 |

| r2 | 0.671 | 0.768 | 0.666 | 0.687 | 0.681 | 0.562 | 0.599 | 0.554 | 0.578 | 0.546 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Ldscl | (3) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ptrlzb | 0.0725 *** (0.011) | 0.0178 *** (0.005) | 0.0366 *** (0.014) |

| ldscl | —— | —— | 2.021 *** (0.265) |

| Xztdmj | 0.000249 (0.002) | −0.000179 (0.000) | 0.000610 (0.002) |

| Szy | −0.00765 (0.012) | −0.00732 *** (0.002) | 0.00715 (0.012) |

| Czzc | 0.000196 *** (0.000) | 0.0000150 ** (0.000) | 0.000166 *** (0.000) |

| Ptzx | −0.0000432 (0.000) | 0.0000114 (0.000) | −0.0000662 (0.000) |

| Ptxx | −0.000572 *** (0.000) | −0.000143 *** (0.000) | −0.000282 *** (0.000) |

| Ylws | 0.000214 (0.000) | 0.0000249 (0.000) | 0.000164 (0.000) |

| Ggts | −0.000217 (0.002) | −0.000192 (0.000) | 0.000172 (0.002) |

| Sjsywz | −0.000804 (0.001) | −0.000166 (0.000) | −0.000468 (0.001) |

| Jck | 0.000115 ** (0.000) | 0.0000112 (0.000) | 0.0000918 ** (0.000) |

| Gdzc | 0.00140 *** (0.000) | 0.000175 *** (0.000) | 0.00104 *** (0.000) |

| _cons | 0.363 *** (0.041) | 0.104 *** (0.007) | 0.153 *** (0.042) |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.494 | 0.234 | 0.584 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Cyjg | (3) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ptrlzb | 0.0725 *** (0.011) | 0.196 ** (0.077) | 0.0639 *** (0.012) |

| Cyjg | —— | —— | 0.0435 ** (0.020) |

| Xztdmj | 0.0249 (0.201) | −0.0128 ** (0.006) | 0.805 (2.023) |

| Szy | 0.0077 (0.012) | −0.0338 ** (0.013) | −0.00618 (0.012) |

| Czzc | 0.000196 *** (0.000) | 0.000142 *** (0.000) | 0.000190 *** (0.000) |

| Ptzx | −0.0000432 (0.000) | 0.000273 * (0.000) | −0.0000551 (0.000) |

| Ptxx | −0.000572 *** (0.000) | −0.000397 ** (0.000) | −0.000555 *** (0.000) |

| Ylws | 0.000214 (0.000) | 0.0000819 * (0.000) | 0.000211 (0.000) |

| Ggts | −0.000217 (0.002) | 0.00611 ** (0.003) | −0.000482 (0.002) |

| Sjsywz | −0.000804 (0.001) | −0.00336 *** (0.001) | −0.000658 (0.001) |

| Jck | 0.000115 ** (0.000) | −0.00000570 (0.000) | 0.000115 ** (0.000) |

| Gdzc | 0.00140 *** (0.000) | 0.00159 *** (0.000) | 0.00133 *** (0.000) |

| _cons | 0.363 *** (0.041) | 1.118 *** (0.104) | 0.315 *** (0.037) |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.494 | 0.201 | 0.498 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Cxnl | (3) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ptrlzb | 0.0725 *** (0.011) | 1.577 *** (0.364) | 0.0452 *** (0.013) |

| Cxnl | —— | —— | 0.0173 *** (0.003) |

| Xztdmj | 0.000249 (0.002) | −0.0844 * (0.043) | 0.00171 (0.002) |

| Szy | −0.00765 (0.012) | −0.728 *** (0.253) | 0.00494 (0.009) |

| Czzc | 0.000196 *** (0.000) | −0.00180 ** (0.001) | 0.000227 *** (0.000) |

| Ptxx | −0.000572 *** (0.000) | −0.00917 *** (0.002) | −0.000414 *** (0.000) |

| Ylws | 0.000214 (0.000) | 0.00172 (0.001) | 0.000185 (0.000) |

| Ggts | −0.000217 (0.002) | 0.101 (0.071) | −0.00196 ** (0.001) |

| Sjsywz | −0.000804 (0.001) | −0.0446 *** (0.015) | −0.0000322 (0.001) |

| Jck | 0.000115 ** (0.000) | −0.000102 (0.000) | 0.000116 ** (0.000) |

| Gdzc | 0.00140 *** (0.000) | 0.0339 *** (0.004) | 0.000809 *** (0.000) |

| _cons | 0.363 *** (0.041) | 4.747 *** (0.869) | 0.281 *** (0.030) |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.494 | 0.467 | 0.548 |

| (1) Rjgdp | (2) Rjgdp | (3) Rjgdp | (4) Rjgdp | (5) Rjgdp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netinmig | 0.0685 *** (0.008) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Netinmig × Hjzd | −0.00321 ** (0.002) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb | —— | 8.742 *** (1.674) | —— | —— | —— |

| Gjrlzb × Hjzd | 47.53 *** (12.123) | ||||

| Ptrlzb | —— | —— | 0.217 (0.252) | —— | —— |

| Ptrlzb × Hjzd | −0.00150 (0.042) | ||||

| Rklr | —— | —— | —— | 1.822 *** (0.540) | —— |

| Rklr × Hjzd | 0.0302 (0.045) | ||||

| Rklc | —— | —— | —— | —— | −0.466 ** (0.222) |

| Rklc × Hjzd | 0.150 *** (0.049) | ||||

| _cons | 0.499 *** (0.041) | 0.242 *** (0.039) | 0.372 *** (0.039) | 0.301 *** (0.046) | 0.367 *** (0.040) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Individual effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Time effect | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 | 4544 |

| r2 | 0.461 | 0.558 | 0.456 | 0.478 | 0.456 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, P.; Li, X.; Yuan, G. Cross-Regional Allocation of Human Capital and Sustainable Development of China’s Regional Economy—Based on the Perspective of Population Mobility. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129807

Li P, Li X, Yuan G. Cross-Regional Allocation of Human Capital and Sustainable Development of China’s Regional Economy—Based on the Perspective of Population Mobility. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129807

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Peng, Xiangrong Li, and Gonglin Yuan. 2023. "Cross-Regional Allocation of Human Capital and Sustainable Development of China’s Regional Economy—Based on the Perspective of Population Mobility" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129807