Revisiting Tourism Development and Economic Growth: A Framework for Configurational Analysis in Chinese Cities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

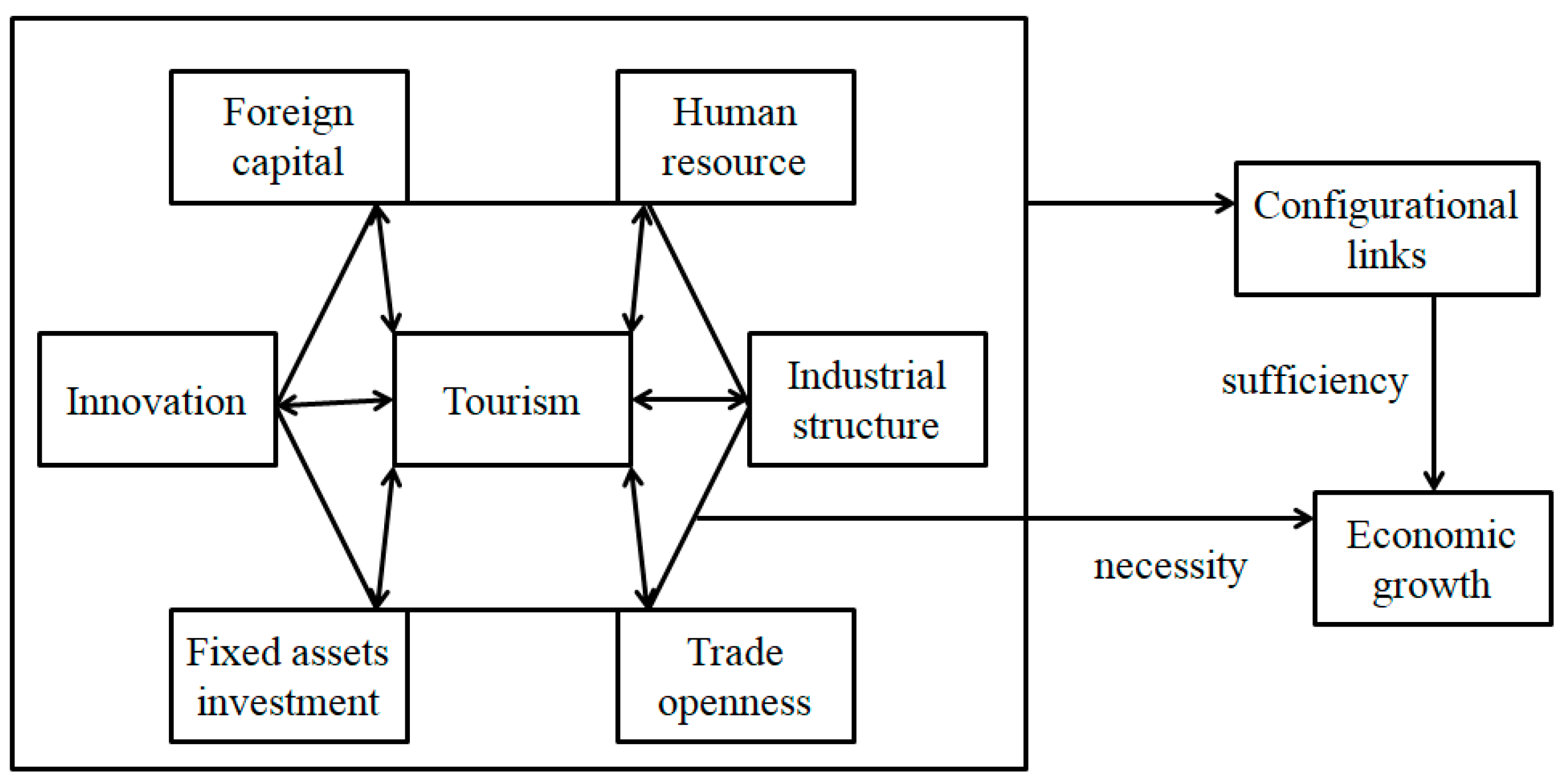

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Necessity Analysis

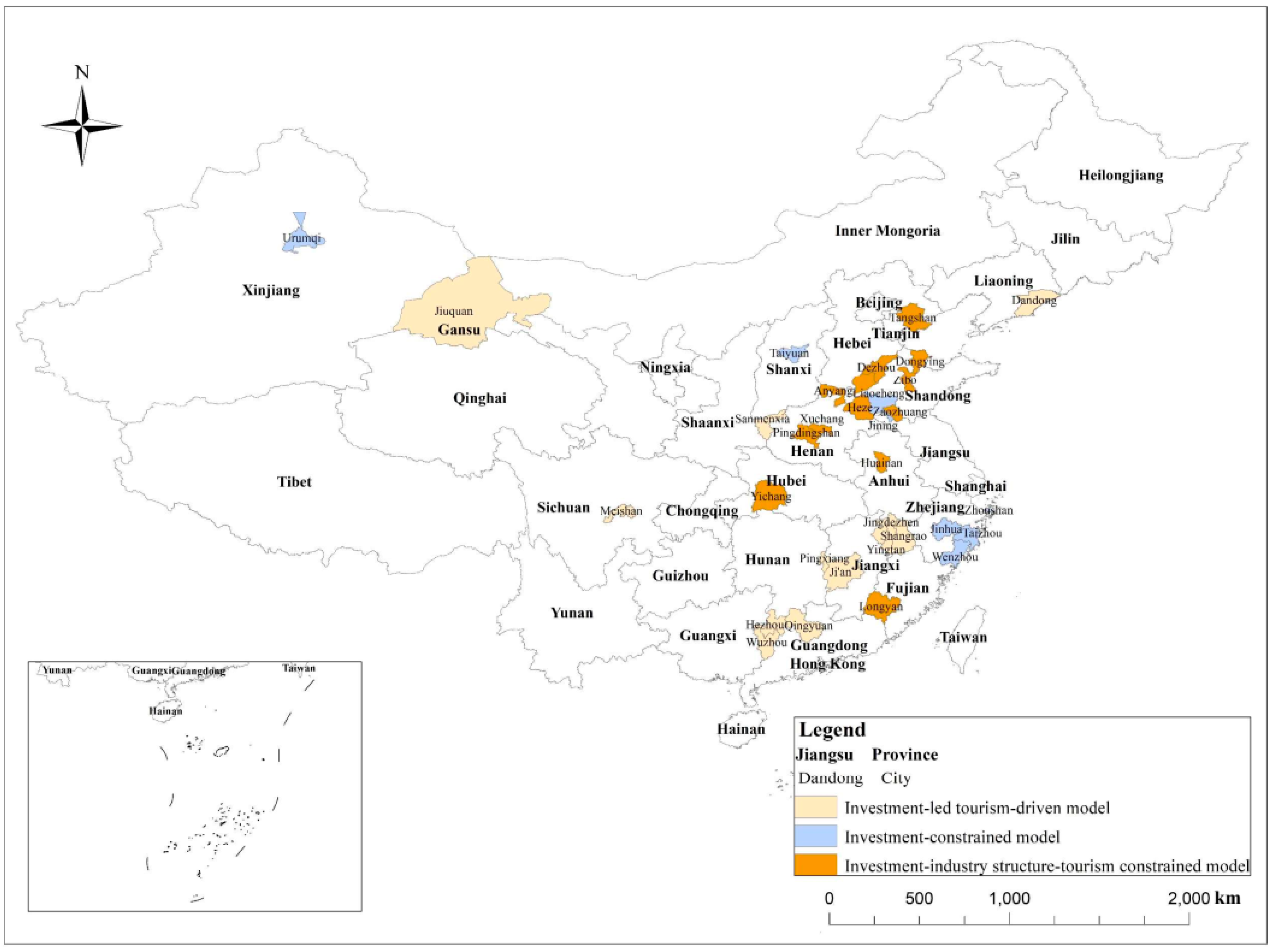

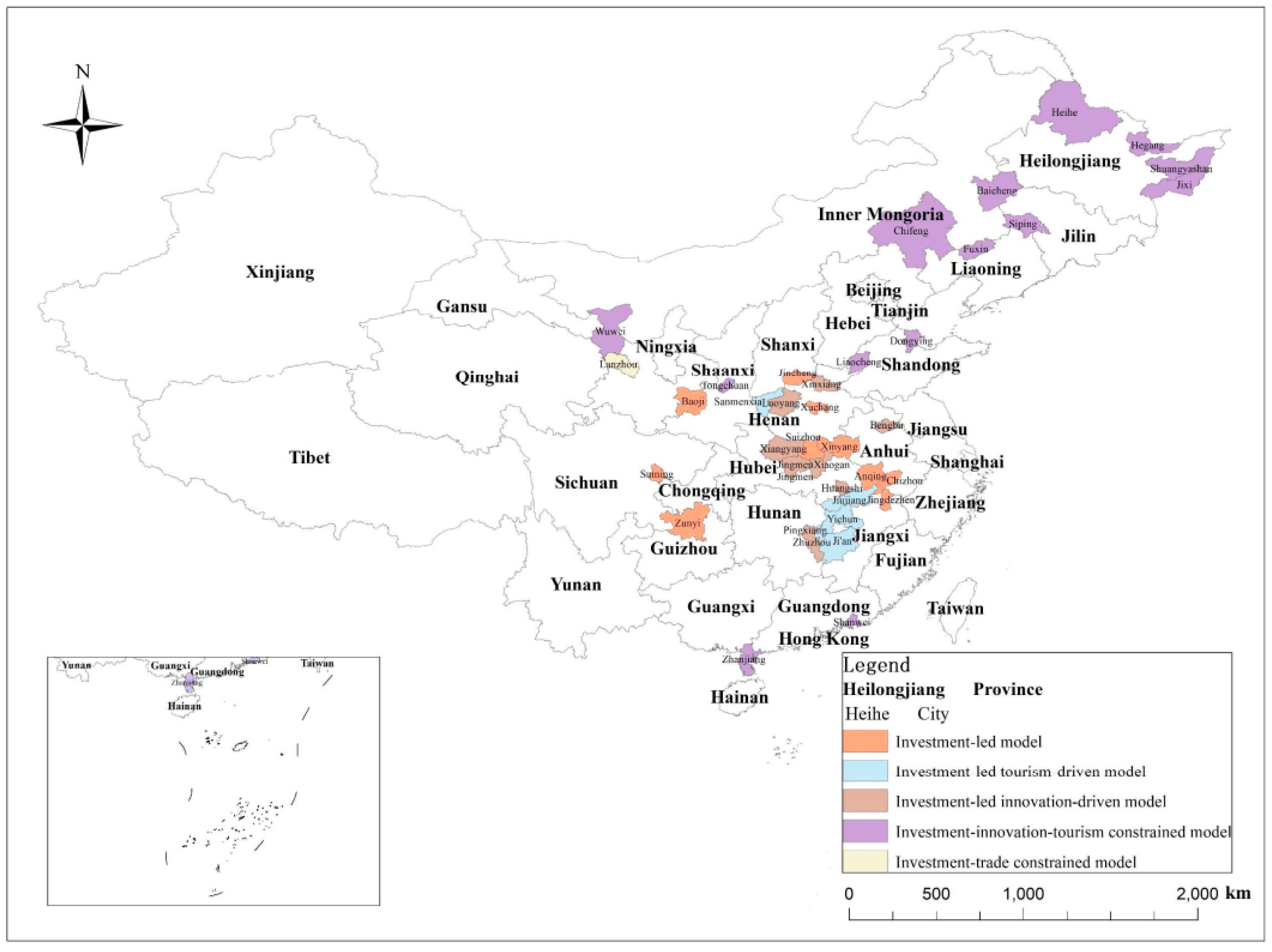

4.2. Sufficiency Analysis

4.3. Robustness Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| City | Province | Population Density (People per Km2) | Tourism Revenue (100 Million Yuan) | Tourist Arrivals (10,000 Person-Times) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment-led tourism-driven model | ||||

| Ji’an | Jiangxi | 190 | 100 | 1415 |

| Wuzhou | Guangxi | 229 | 52 | 665 |

| Shangrao | Jiangxi | 289 | 143 | 1987 |

| Qingyuan | Guangdong | 194 | 108 | 667 |

| Yingtan | Jiangxi | 316 | 45 | 612 |

| Pingxiang | Jiangxi | 484 | 48 | 731 |

| Meishan | Sichuan | 413 | 65 | 991 |

| Jiuquan | Gansu | 7 | 38 | 406 |

| Hezhou | Guangxi | 166 | 38 | 504 |

| Sanmenxia | Henan | 213 | 80 | 1459 |

| Jingdezhen | Jiangxi | 302 | 67 | 1325 |

| Dandong | Liaoning | 160 | 219 | 2281 |

| Investment-constrained model | ||||

| Taiyuan | Shanxi | 602 | 230 | 2023 |

| Zibo | Shandong | 760 | 214 | 2561 |

| Wenzhou | Zhejiang | 754 | 332 | 3526 |

| Jinhua | Zhejiang | 490 | 284 | 2945 |

| Jining | Shandong | 722 | 233 | 3018 |

| Taizhou | Zhejiang | 594 | 273 | 3296 |

| Dongying | Shandong | 247 | 45 | 640 |

| Urumqi | Xinjiang | 226 | 75 | 782 |

| Zhoushan | Zhejiang | 769 | 142 | 2139 |

| Liaocheng | Shandong | 671 | 51 | 876 |

| Tangshan | Hebei | 534 | 77 | 1538 |

| Investment–industry structure tourism-constrained model | ||||

| Zibo | Shandong | 760 | 214 | 2561 |

| Dongying | Shandong | 247 | 45 | 640 |

| Huainan | Anhui | 422 | 26 | 602 |

| Zaozhuang | Shandong | 817 | 61 | 948 |

| Pingdingshan | Henan | 622 | 69 | 898 |

| Anyang | Henan | 700 | 105 | 1401 |

| Xuchang | Henan | 862 | 32 | 608 |

| Yichang | Hubei | 191 | 104 | 1542 |

| Dezhou | Shandong | 538 | 47 | 971 |

| Liaocheng | Shandong | 671 | 51 | 876 |

| Tangshan | Hebei | 534 | 77 | 1538 |

| Heze | Shandong | 682 | 36 | 669 |

| Longyan | Fujian | 134 | 70 | 987 |

| City | Province | Population Density (People per Km2) | Tourism Revenue (100 Million Yuan) | Tourist Arrivals (10,000 Person-Times) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment-led model | ||||

| Xuchang | Henan | 893 | 214 | 3197 |

| Jingmen | Hubei | 234 | 198 | 3269 |

| Baoji | Shaanxi | 208 | 937 | 12,267 |

| Jincheng | Shanxi | 250 | 669 | 7329 |

| Suining | Sichuan | 599 | 563 | 5831 |

| Suizhou | Hubei | 230 | 179 | 2835 |

| Chizhou | Anhui | 177 | 777 | 7043 |

| Jingdezhen | Jiangxi | 319 | 719 | 5523 |

| Zunyi | Guizhou | 205 | 2106 | 19,300 |

| Anqing | Anhui | 349 | 818 | 7754 |

| Xinyang | Henan | 344 | 282 | 4830 |

| Investment-led tourism-driven model | ||||

| Ji’an | Jiangxi | 195 | 983 | 7790 |

| Chizhou | Anhui | 177 | 777 | 7043 |

| Baoji | Shaanxi | 208 | 937 | 12,267 |

| Jincheng | Shanxi | 250 | 669 | 7329 |

| Suining | Sichuan | 599 | 563 | 5831 |

| Jingdezhen | Jiangxi | 319 | 669 | 7329 |

| Yichun | Jiangxi | 299 | 910 | 7987 |

| Sanmenxia | Henan | 217 | 381 | 4391 |

| Zunyi | Guizhou | 205 | 2106 | 19,300 |

| Anqing | Anhui | 349 | 818 | 7754 |

| Pingxiang | Jiangxi | 507 | 704 | 5830 |

| Jiujiang | Jiangxi | 248 | 1161 | 9115 |

| Investment-led innovation-driven model | ||||

| Luoyang | Henan | 454 | 1692 | 14,146 |

| Baoji | Shaanxi | 208 | 669 | 7329 |

| Bengbu | Anhui | 573 | 356 | 5122 |

| Xinxiang | Henan | 701 | 356 | 5202 |

| Xiangyang | Hubei | 288 | 478 | 6185 |

| Xiaogan | Hubei | 553 | 195 | 3022 |

| Zhuzhou | Hunan | 358 | 638 | 6466 |

| Anqing | Anhui | 349 | 818 | 7754 |

| Xuchang | Henan | 893 | 214 | 3197 |

| Jingmen | Hubei | 234 | 198 | 3269 |

| Jingdezhen | Jiangxi | 319 | 719 | 5523 |

| Zunyi | Guizhou | 205 | 2106 | 19,300 |

| Huangshi | Hubei | 539 | 192 | 2839 |

| Investment–innovation tourism-constrained model | ||||

| Jixi | Heilongjiang | 75 | 83 | 1233 |

| Baicheng | Jilin | 73 | 95 | 530 |

| Shuangyashan | Heilongjiang | 62 | 32 | 934 |

| Heihe | Heilongjiang | 23 | 115 | 1313 |

| Tongchuan | Shaanxi | 201 | 163 | 2493 |

| Hegang | Heilongjiang | 67 | 64 | 669 |

| Liaocheng | Shandong | 707 | 220 | 2517 |

| Siping | Jilin | 221 | 26 | 550 |

| Wuwei | Gansu | 56 | 113 | 1957 |

| Shanwei | Guangdong | 620 | 173 | 971 |

| Fuxin | Liaoning | 169 | 118 | 1632 |

| Chifeng | Inner Mongolia | 48 | 421 | 1987 |

| Zhanjiang | Guangdong | 555 | 601 | 2845 |

| Dongying | Shandong | 264 | 206 | 2018 |

| Investment–trade-constrained model | ||||

| Lanzhou | Gansu | 287 | 767 | 8211 |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Tourist Attractions and Economic Growth in China: A Difference-in-Differences Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, F.F.; Erum, N.; Bekun, F.V. How does institutional quality moderates the impact of tourism on economic growth? Startling evidence from high earners and tourism-dependent economies. Tour. Econ. 2021, 28, 1311–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, B.; Gaubert, C. Tourism and Economic Development: Evidence from Mexico’s Coastline. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 2245–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harb, G.; Bassil, C. Harnessing cross-region disparities to assess the impact of tourism on regional growth in Europe. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Seetanah, B.; Jaffur, Z.R.K.; Moraghen, P.G.W.; Sannassee, R.V. Tourism and Economic Growth: A Meta-regression Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aratuo, D.N.; Etienne, X.L. Industry level analysis of tourism-economic growth in the United States. Tour. Manag. 2018, 70, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, C.L.; Carmignani, F.; Moyle, B.; Anwar, S. Beyond Dutch Disease: Are there mediators of the mining–tourism nexus? Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 744–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Necessary condition analysis (NCA) logic and methodology of “necessary but not sufficient” causality. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. A qualitative comparative analysis of tourism and gender equality in emerging economies. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Conducting Necessary Condition Analysis for Business and Management Students; Sage: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J.; van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A Statistical Significance Test for Necessary Condition Analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L. Tourism, economic growth, and tourism-induced EKC hypothesis: Evidence from the Mediterranean region. Empir. Econ. 2019, 60, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J. Analyzing the Bidirectional Relationship between Tourism Growth and Economic Development. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Tourism, economic growth, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in China. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1060–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnari, S.; Crilly, D.; Misangyi, V.F.; Greckhamer, T.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Capturing Causal Complexity: Heuristics for Configurational Theorizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 778–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.E.; Liu, Y. State-directed tourism urbanisation in China’s Hengqin. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Ma, X. International tourism and economic vulnerability. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.-P.; Ramos, P.N.; Lahr, M.L. The rise of the sharing economy: Guesthouse boom and the crowding-out effects of tourism in Lisbon. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, I.; Marcher, A.; Volgger, M.; Pechlaner, H. The special characteristics of tourism innovation networks: The case of the Regional Innovation System in South Tyrol. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A.; Prentice, C. Using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis for a finer-grained understanding of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Ragin, C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baharumshah, A.Z.; Thanoon, M.A.-M. Foreign capital flows and economic growth in East Asian countries. China Econ. Rev. 2006, 17, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicea, C.; Marinescu, C. Bibliometric analysis of foreign direct investment and economic growth relationship. A research agenda. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 22, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Tucci, C.L. The innovation–economic growth nexus: Global evidence. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Tan, J. Exploring the coupling and forecasting of financial development, technological innovation, and economic growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 163, 120466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, S.; Murshed, M.; Umarbeyli, S.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Ahmad, M.; Tufail, M.; Wahab, S. Do natural resources abundance and human capital development promote economic growth? A study on the resource curse hypothesis in Next Eleven countries. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanger, A.; Usman, M.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. The linkages between natural resources, human capital, globalization, economic growth, financial development, and ecological footprint: The moderating role of technological innovations. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hong, X.; Peng, K. A spatial panel analysis of carbon emissions, economic growth and high-technology industry in China. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2019, 49, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tang, J. Industrial structure change and economic growth: A China-Russia comparison. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 47, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanikkaya, H. Trade openness and economic growth: A cross-country empirical investigation. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 72, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchet-Bourdon, M.; Le Mouël, C.; Vijil, M. The relationship between trade openness and economic growth: Some new insights on the openness measurement issue. World Econ. 2018, 41, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Li, S. Energy investment, economic growth and carbon emissions in China—Empirical analysis based on spatial Durbin model. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, R. Is China’s economic growth decoupled from carbon emissions? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Ridderstaat, J.; Bąk, M.; Zientara, P. Tourism specialization, economic growth, human development and transition economies: The case of Poland. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, B.; Ladu, M.G.; Royuela, V. Human Development and Tourism Specialization. Evidence from a Panel of Developed and Developing Countries. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adeosun, O.T.; Popogbe, O.O. Population growth and human resource utilization nexus in Nigeria. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, K.; Li, S. Ecosystem of doing business, total factor productivity and multiple patterns of high-quality development of Chinese cities: A configuration analysis based on complex systems view. Manag. World 2022, 38, 127–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. Trade openness, economic growth, and energy intensity in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, R. Whether foreign direct investment can promote high-quality economic development under environ-mental regulation: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21674–21683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Du, J.; Tan, K.H. Impact of fiscal decentralization on green total factor productivity. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 205, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, B.; Woldendorp, J.; Keman, H. Examining variation in economic performance using fuzzy-sets. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2011 China City Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2020 China City Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Greckhamer, T.; Gur, F.A. Disentangling combinations and contingencies of generic strategies: A set-theoretic configurational approach. Long Range Plan. 2021, 54, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vita, G.; Kyaw, K.S. Tourism specialization, absorptive capacity, and economic growth. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Huang, S. Revisiting the Tourism-Led Economic Growth Hypothesis: The Case of China. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Williams, A.M.; Park, S.; Chen, J.L. Spatial spillovers of agglomeration economies and productivity in the tourism industry: The case of the UK. Tour. Manag. 2020, 82, 104201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, J. The Spatial Spillover Effect and Its Impact on Tourism Development in a Megacity in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Yan, B. Study on the interactive influence between economic growth and environmental pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 39442–39465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Kot, S.; Hussain, H.I.; Kamarudin, F. The natural resources curse-economic growth hypotheses: Quantile–on–Quantile evidence from top Asian economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E.; Qian, N. On the road: Access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 145, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Unit | Mean | STD. DEV | Min. | Max. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | ||

| Economic growth | % | 14.58 | 6.44 | 2.16 | 1.98 | 9.60 | −3.60 | 25.10 | 11.80 |

| Tourism | / | 0.1004 | 0.3088 | 0.0896 | 0.2447 | 0.0091 | 0.0331 | 0.7832 | 2.2796 |

| Foreign capital | / | 0.0182 | 0.0128 | 0.0178 | 0.0146 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1277 | 0.0613 |

| Human resources | / | 9821 | 17,950 | 403,601 | 75,395 | 0 | 0 | 404,020 | 786,890 |

| Innovation | / | 6.6447 | 52.9559 | 26.3843 | 232.3673 | 0.0085 | 0.0058 | 348.8300 | 3393.3000 |

| Industrial structure | / | 0.7502 | 1.3722 | 0.3640 | 0.6558 | 0.0833 | 0.4270 | 3.0605 | 4.9456 |

| Fixed asset investment | / | 0.7263 | 0.8710 | 0.2530 | 0.3535 | 0.1063 | 0.1882 | 1.6451 | 2.4108 |

| Trade openness | / | 0.2190 | 0.1632 | 0.5633 | 0.2616 | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | 7.8462 | 2.4834 |

| Variable | Fully in | Crossover Points | Fully Out | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | |

| Economic growth | 18.40 | 9.00 | 14.20 | 6.80 | 11.50 | 2.80 |

| Tourism | 0.1996 | 0.7285 | 0.0807 | 0.2465 | 0.0229 | 0.0743 |

| Foreign capital | 0.0551 | 0.0470 | 0.0129 | 0.0064 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 |

| Human resources | 44,076 | 84,429 | 697 | 1142 | 42 | 62 |

| Innovation | 30.7825 | 199.5719 | 0.5437 | 6.5965 | 0.0489 | 0.2660 |

| Industrial structure | 1.2287 | 2.6402 | 0.685 | 1.2090 | 0.3444 | 0.6855 |

| Fixed asset investment | 1.1770 | 1.4371 | 0.7008 | 0.8595 | 0.3529 | 0.3096 |

| Trade openness | 0.7412 | 0.5520 | 0.0766 | 0.0708 | 0.0068 | 0.0070 |

| Condition | Economic Growth (Consistency) | ~Economic Growth (Consistency) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | |

| Tourism | 0.6603 | 0.6328 | 0.6325 | 0.6052 |

| ~tourism | 0.6671 | 0.6670 | 0.6923 | 0.7159 |

| Foreign capital | 0.6285 | 0.6380 | 0.5919 | 0.5395 |

| ~foreign capital | 0.6841 | 0.6454 | 0.7182 | 0.7640 |

| Human resources | 0.6030 | 0.5716 | 0.6032 | 0.6198 |

| ~human resources | 0.7322 | 0.7418 | 0.7293 | 0.7160 |

| Innovation | 0.5247 | 0.5742 | 0.6376 | 0.5715 |

| ~innovation | 0.8132 | 0.7304 | 0.6976 | 0.7548 |

| Industrial structure | 0.6374 | 0.5913 | 0.6926 | 0.6761 |

| ~industrial structure | 0.7082 | 0.7311 | 0.6502 | 0.6693 |

| Fixed asset investment | 0.6909 | 0.7154 | 0.6270 | 0.6107 |

| ~fixed asset investment | 0.6467 | 0.6066 | 0.7078 | 0.7342 |

| Trade openness | 0.5534 | 0.5697 | 0.6147 | 0.6161 |

| ~trade openness | 0.7673 | 0.7242 | 0.7035 | 0.6988 |

| Condition | Methods | Accuracy | Ceiling Zone | Scope | Effect Size (d) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 | ||

| Tourism | CR | 100% | 100% | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.645 | 0.377 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.009 | 0.014 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.481 | 0.244 | |

| Foreign capital | CR | 99.3% | 100% | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.244 | 0.480 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.278 | 0.413 | |

| Human resource | CR | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 0.005 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.001 | |

| Innovation | CR | 100% | 96.7% | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.000 | 0.071 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.069 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.000 | 0.073 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

| Industrial structure | CR | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.600 | 0.278 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.597 | 0.102 | |

| Fixed asset investment | CR | 100% | 99.6% | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.945 | 0.683 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.942 | 0.707 | |

| Trade openness | CR | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| CE | 100% | 100% | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Economic Growth | Tourism | Foreign Capital | Human Resources | Innovation | Industrial Structure | Fixed Asset Investment | Trade Openness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 10 | NN/0.2 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/0.0 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 20 | 0.1/0.4 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/0.1 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 30 | 0.2/0.6 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/0.2 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 40 | 0.3/0.8 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/0.4 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 50 | 0.5/1.0 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/0.5 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 60 | 0.6/1.2 | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/NN | NN/0.6 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 70 | 0.7/1.4 | NN/0.2 | NN/NN | NN/7.1 | NN/0.7 | NN/NN | NN/NN |

| 80 | 0.8/1.6 | 1.3/0.5 | NN/NN | NN/17.6 | NN/0.8 | 0.2/NN | NN/NN |

| 90 | 0.9/1.8 | 4.0/0.8 | NN/0.6 | NN/28.1 | NN/0.9 | 0.6/0.0 | NN/NN |

| 100 | 1.0/2.0 | 6.7/1.0 | NN/15.1 | NN/38.7 | 1.0/1.0 | 1.0/5.9 | NN/NN |

| Condition | 2010 | 2019 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Growth | ~Economic Growth | Economic Growth | ~Economic Growth | |||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | |

| Tourism | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | |||

| Foreign capital | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ○ |

| Human resources | ⊗ | ● | ■ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ■ | ||

| Innovation | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ||

| Industrial structure | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ● | ||

| Fixed assets investment | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ |

| Trade openness | ● | ■ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ⊗ | ||||

| Raw coverage | 0.2993 | 0.2925 | 0.2884 | 0.2578 | 0.3472 | 0.2919 | 0.3053 | 0.3411 | 0.2534 | 0.1864 |

| Unique coverage | 0.2993 | 0.0527 | 0.0486 | 0.0180 | 0.0159 | 0.0312 | 0.0188 | 0.1196 | 0.0405 | 0.0193 |

| Consistency | 0.9155 | 0.9458 | 0.9446 | 0.9450 | 0.9084 | 0.9094 | 0.9232 | 0.9133 | 0.9317 | 0.9503 |

| Solution coverage | 0.2993 | 0.3592 | 0.3972 | 0.4049 | ||||||

| Solution consistency | 0.9155 | 0.9343 | 0.9036 | 0.9066 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Revisiting Tourism Development and Economic Growth: A Framework for Configurational Analysis in Chinese Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310000

Zhang Y, Zhang J. Revisiting Tourism Development and Economic Growth: A Framework for Configurational Analysis in Chinese Cities. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310000

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yan, and Jiekuan Zhang. 2023. "Revisiting Tourism Development and Economic Growth: A Framework for Configurational Analysis in Chinese Cities" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310000