Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: An Empirical Study in Midyat, Turkey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Urban Sustainable Tourism Development and City Image

2.2. Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development Impacts

2.3. Support for Tourism Development

3. Materials and Methods

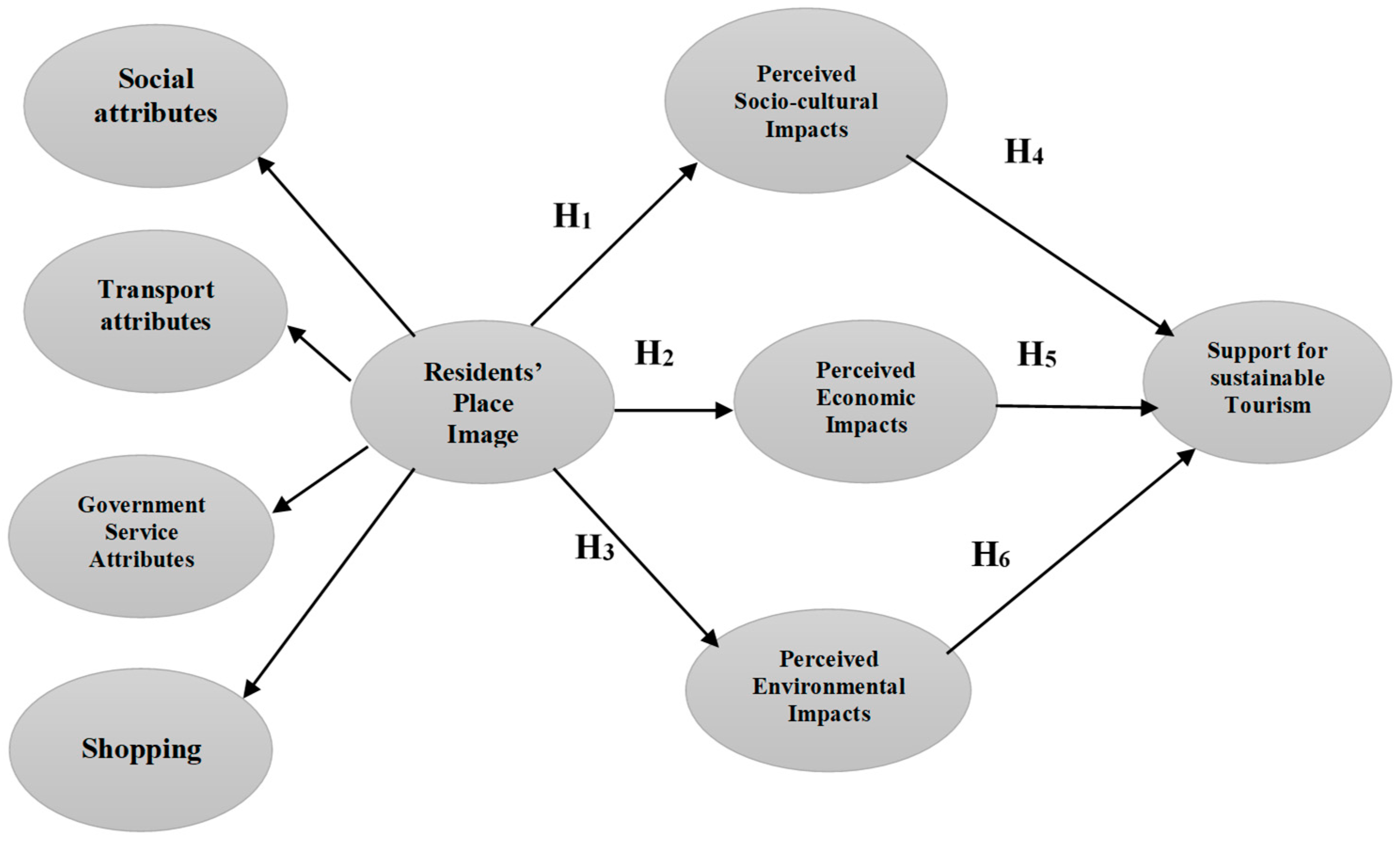

3.1. Study Method

3.2. Study Instrument

3.3. Study Location

3.4. Study Sampling

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample Population

4.2. Validity and Reliability Analysis of the Scale and the Measurement Model (Outer Model)

4.3. Testing the Structural Model (Inner Model)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M. Explaining residents’ behavioral support for tourism through two theoretical frameworks. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, K.; Akay, B.; Demirel, S. The effect of COVID-19 on operating costs: The perspective of hotel managers in Antalya, Turkey. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 18, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazimahmed, T.; Kassemo, A.; Alajloni, A.; Alomran, A.; Ragab, A.; Shaker, E. Effect of internal corporate social responsibility activities on tourism and hospitality employees’ normative commitment during COVID-19. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 18, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Subhi, A.A.; Meesala, K.M. Community perception and attitude towards sustainable tourism and environmental protection measures: An exploratory study in Muscat, Oman. Economies 2022, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, N.; Rita, P. COVID 19: The catalyst for digital transformation in the hospitality industry? Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ababneh, M.M.; Al-Shakhsheer, F.J.; Habiballah, M.; Al-Badarneh, M.B. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism workers’ health and well-being in Jordan. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 18, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.H. Impact of investment in tourism infrastructure development on attracting international visitors: A nonlinear panel ARDL approach using Vietnam’s data. Economies 2021, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, A.; Pestana, M.H.; Santos, J.A.C.; Fernández-Gámez, M.A. Senior tourists’ motivations for visiting cultural destinations: A cluster approach. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 32, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, C.A.M.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Remoaldo, P. The relationship between creative tourism and local development: A bibliometric approach for the period 2009–2019. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, G.; Buckley, J.; Flanagan, S. City break motivation. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 22, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Connell, J. Urban tourism. In Tourism A Modern Synthesis; Page, S.J., Connell, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mira, M.R.C.; Mónico, L.S.M.; Breda, Z.M.J. Territorial dimension in the internationalisation of tourism destinations: Structuring factors in the post-COVID-19. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T. Residents’ attitudes towards overtourism from the perspective of tourism impacts and cooperation: The case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, C.M. Urban Tourism: The Visitor Economy and the Growth of Large Cities, 2nd ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, P.G.; Ferreira, A.M.; Costa, C. Tourism and third sector organisations: Synergies for responsible tourism development? Tour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 18, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Salazar, J. Complementing theories to explain emotional solidarity. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, M.F.; Linares, J.F.; Carrillo, E.; Mendes, F.M. Proposal for a framework to develop sustainable tourism on the Santurbán Moor, Colombia, as an alternative source of income between environmental sustainability and mining. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgiç, A.; Birdir, K. Key success factors on loyalty of festival visitors: The mediating effect of festival experience and festival image. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2020, 16, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, N.; Milićević, S. Residents’ perceptions of economic ımpacts of tourism development in Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 95, 01006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Veiga, C.; Santos, J.A.C.; Águas, P. Sustainability as a success factor for tourism destinations: A systematic literature review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gámez, M.A.; Santos, J.A.C.; Diéguez-Soto, J.; Campos-Soria, J.A. The effect of countries’ health and environmental conditions on restaurant reputation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Ferreira, A.; Costa, C.; Santos, J.A.C. A model for the development of innovative tourism products: From service to transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, G.J.; Verdian, M.S. The environmental effects of tourism development in Noushahr. Open J. Ecol. 2016, 6, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plebańczyk, K. Positive and negative effects of cultural tourism development: Changes and dynamics in the Polish region of Podlasie. In Cultural Sustainability, Tourism and Development; Duxbury, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejia, M.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenidogan, A.; Gurcaylilar-Yenidogan, T.; Tetik, N. Environmental management and hotel profitability: Operating performance matters. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Small island urban tourism: A residents’ perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 13, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, C.; Santos, M.C.; Águas, P.; Santos, J.A.C. Sustainability as a key driver to address challenges. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troanca, D. The impact of tourism development on urban environment. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2012, 7, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte, J.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Sousa, A.; Oliveira, A. Tourism planning in the Azores and feedback from visitors. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Erul, E.; Suess, C.; Kong, I.; Boley, B.B. Which construct is better at explaining residents’ involvement in tourism; emotional solidarity or empowerment? Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3372–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, S.; Stojanović, V. Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism development: A case study of the Gradac River gorge, Valjevo (Serbia). Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 47, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskin, M.; Tiril, A.; Bozkurt, A. Coastal tourism development in Sinop as an emerging rural destination: A preliminary study from the residents’ perspective. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2020, 16, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A.; Alagöz, G.; Güneş, E. Socio-cultural, economic, and environmental effects of tourism from the point of view of the local community. J. Tour. Serv. 2020, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Nunkoo, R. City image and perceived tourism impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C. Resident support for tourism development in rural Midwestern (USA) communities: Perceived tourism ımpacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stylidis, D.; Sit, J.; Biran, A. An exploratory study of residents’ perception of place ımage: The case of Kavala. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. The role of place image dimensions in residents’ support for tourism development. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huayhuaca, C.A.; Cottrell, S.; Raadik, J.; Gradl, S. Resident perceptions of sustainable tourism development: Frankenwald Nature Park, Germany. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2010, 3, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M. Sustainable tourism development and residents’ perceptions in World Heritage Site destinations. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Wondirad, A. Tourism network in urban agglomerated destinations: ımplications for sustainable tourism destination development through a critical literature review. Sustainability 2020, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, W.; Engelhardt, R. Managing urban heritage areas in the context of sustainable tourism. In The Planning and Management of Responsible Urban Heritage Destinations in Asia; Jamieson, P.W., Engelhardt, P.R.A., Eds.; Chapter 4; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our common future revisited. Brown J. World Aff. 1996, III, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Veyret, Y.; Le Goix, R. Atlas des Villes Durables; Éditions Autrement: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arcentales, S.D.A.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Rosen, M.A. Sustainable cities. In Building Sustainable Cities; Alvarez-Risco, A., Rosen, M., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., Marinova, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, R. Designing the sustainable city. In Designing Sustainable Cities. Contemporary Urban Design Thinking; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, K.; Knüvener, T. On sustainable sustaining city streets. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaivani, R.; Suresh, M.V.; Prasad, S.S.; Kaleel, M.I.M. Urban tourism: A role of government policy and strategies of tourism in Tamil Nadu. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium, Oluvil, Sri Lanka, 6–7 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Report. 2017. Available online: https://unesco.se/in-english/ (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Andari, R. Developing a sustainable urban tourism. THE J. Tour. Hosp. Essent. 2019, 9, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.C. Sustaining urban tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, I.; Ünsever, I. Importance of tourism equinox for sustainable city tourism. In Cultural and Tourism Innovation in the Digital Era; Katsoni, V., Spyriadis, T., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics: Cham, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, R. Conviviality and everyday life: The appeal of new areas of London for visitors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Uslu, A.; Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Place-oriented or people-oriented concepts for destination loyalty: Destination ımage and place attachment versus perceived distances and emotional solidarity. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, T.; Haley, A.J. Residents’ opinion of tourism development in the historic city of York, England. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarez, R.D.; Lopez, G.M.; Sawate, S.E.; Bautista, J.P.; Gayagay, M.C.; Lamberte, M.D.; Julaquit, A.L.; De Jesus, R.J. Perceived tourism impacts of tourists on the environment of the Philippine Military Academy in Baguio City Philippines. Sustain. Geosci. Geotour. 2020, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, J. The influence of place identity on perceived tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musadad, M.; Nurlena, N. Perceived tourism impacts in pindul cave, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. J. Bus. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıngır, S.; Çelik, S.; Sancar, M.F.; Akay, B. Perception of local community on tourism: A study in the Southeast Anatolia region (SEAR). Nişantaşı Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Pratt, S.; Wang, Y. Core self-evaluations and residents’ support for tourism: Perceived “tourism impacts as mediators”. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec Rudež, H.; Vodeb, K. Perceived tourism impacts in municipalities with different tourism concentration. Tour. Internat. Interdis. J. 2010, 58, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.M.; McIntosh, W.A. Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Kim, S.S.; Wong, A.K.F. Residents’ perceptions of desired and perceived tourism impact in Hainan Island. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodeb, K.; Fabjan, D.; Krstinić Nižić, M. Residents’ perceptions of tourism ımpacts and support for tourism development. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 27, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekerşen, Y.; Canöz, F. Tourists’ attitudes toward green product buying behaviours: The role of demographic variables. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 18, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.C.; Fernánjdez-Gámez, M.A.; Guevara-Plaza, A.; Santos, M.C.; Pestana, M.H. The sustainable transformation of business events: Sociodemographic variables as determinants of attitudes towards sustainable academic conferences. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2023, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Sharpley, R. Tourism and Development in the Developing World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Enemuo, O.B.; Oduntan, O.C. Social impact of tourism development on host communities of Osun Oshogbo sacred grove. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development and New Tourism in the Third World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sunlu, U. Environmental impacts of tourism. In Local Resources and Global Trades: Environments and Agriculture in the Mediterranean Region; Camarda, D., Grassini, L., Eds.; CIHEAM: Bari, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, E.; Alagöz, G.; Uslu, A. Yerel Halkın Sürdürülebilir Turizme Yönelik Tutumu: Fethiye Örneği. Uluslararası Türk Dünyası Tur. Araştırmaları Derg. 2020, 5, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Uslu, A.; Cinar, K.; Woosnam, K.M. Using a value-attitude-behaviour model to test residents’ pro-tourism behaviour and involvement in tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroinsong, F.; Sendouw, R. Streetscape enhancement for supporting city tourism development. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frleta, D.S.; Badurina, J.Đ. Factors affecting residents’ support for cultural tourism development. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference ToSEE—Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe 2019, Opatija, Croatia, 16–18 May 2019; pp. 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardin Province Culture and Tourism Head Office. Available online: https://mardin.ktb.gov.tr/TR-56489/midyat-tarihcesi.html (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Governorship of Midyat District, 2018. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/turkiye/mardinin-incisi-midyata-turist-ilgisi/1218477 (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS Release 10 for Windows; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Afthanorhan, W.M.A.B.W. A comparison of partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and covariance based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) for confirmatory factor analysis. Int. J. Eng. Innov. Technol. 2008, 2, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarsted, M. A new criterion for assesing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, K.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using smartpls. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, A.G. A First Course Instructural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modelling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Slabbert, E.; Plessis, E.; Digun-Aweto, O. Impacts of tourism in predicting residents’ opinions and interest in tourism activities. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 19, 819–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. An examination of locals’ attitudes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M.; Williams, R. A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. J. Travel Res. 1997, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović Bajrami, D.; Radosavac, A.; Cimbaljević, M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, Y.A. Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: Implications for Rural Communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Carrus, G.; Martorella, H.; Bonnes, M. Local identity processes and environmental attitudes in land use changes: The case of natural protected areas. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Bonaiuto, M.; Bonnes, M. Environmental concern, regional ıdentity, and support for protected areas in Italy. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.; Tarrant, M. Linking place preferences with place meaning: An examination of the relationships between place motivation and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Percentage (%) | Variables | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 356) | (n = 356) | ||

| Gender (%) | Occupation (%) | ||

| Male | 58.7 | Student | 7.6 |

| Female | 41.3 | White collar worker | 60.6 |

| Age Group (%) | Blue collar worker | 7.3 | |

| 18–24 age | 11.8 | Own business | 6.5 |

| 25–34 age | 55.6 | Other | 18.0 |

| 35–44 age | 26.1 | Length of residency (%) | |

| 45–54 age | 4.2 | Less than 1 year | 10.7 |

| 55–64 age | 2.2 | 1–5 | 20.2 |

| Level of Education (%) | 6–10 | 11.2 | |

| Primary school | 4.5 | 11–15 | 4.8 |

| High school | 13.2 | 16–20 | 9.0 |

| Associate degree | 7.3 | 21 years and more | 44.1 |

| University graduate | 63.5 | Monthly Income (TL) (%) | |

| Master’s or Ph.D. | 11.1 | No income | 18.5 |

| Marital status (%) | Minimum wage | 5.3 | |

| Married | 54.2 | TL 3000–4000 | 11.5 |

| Single | 45.8 | TL 4000–5000 | 28.7 |

| Place of birth (%) | TL 5000–6000 | 22.5 | |

| Midyat | 60.1 | TL 6001 and more | 13.5 |

| Mardin | 12.9 | ||

| Other places | 27.0 |

| Dimensions and Items (n = 356) | Standardized Factor Loading | t-Values | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Order | ||||

| Transport Attributes (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.833; CR = 0.90; AVE = 0.75) | ||||

| Midyat’s road connections are sufficient. a | 0.883 | 47.875 | 2.15 | 1.326 |

| Midyat’s traffic is free/easy. a | 0.851 | 45.249 | 2.55 | 1.353 |

| Midyat’s roads are well maintained. a | 0.863 | 44.130 | 2.11 | 1.249 |

| Social Attributes (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.823; CR = 0.89; AVE = 0.74) | ||||

| Unfriendly-Friendly * | 0.845 | 37.012 | 4.20 | 1.067 |

| Distrusting-Trusting * | 0.881 | 49.814 | 4.22 | 1.108 |

| Hostile-Supportive * | 0.851 | 31.022 | 4.46 | 0.889 |

| Government Service Attributes (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.842; CR = 0.89; AVE = 0.68) | ||||

| There are enough business areas in Midyat. a | 0.764 | 28.359 | 2.28 | 1.169 |

| One can trust the municipality because it makes healthy decisions. a | 0.888 | 60.226 | 2.33 | 1.197 |

| I am pleased with the services of the municipality oriented towards houses in Midyat. a | 0.829 | 37.358 | 2.38 | 1.287 |

| Public transportation is sufficient in Midyat. a | 0.813 | 38.955 | 2.40 | 1.323 |

| Shopping (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.840; CR = 0.893; AVE = 0.676) | ||||

| There is a wide shopping variety in Midyat. a | 0.816 | 41.440 | 2.34 | 1.249 |

| One can find good quality home utilities stores. a | 0.858 | 50.630 | 2.63 | 1.211 |

| There are different types of restaurants in Midyat. a | 0.842 | 42.852 | 2.72 | 1.242 |

| There are markets in eligible locations in Midyat. a | 0.768 | 33.053 | 3.36 | 1.306 |

| Perceived Socio-Cultural Impacts (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.784; CR = 0.86; AVE = 0.61) | ||||

| The recreation areas/places are sufficient in Midyat. a | 0.755 | 20.014 | 2.00 | 1.153 |

| The cultural activities/entertainment are sufficient in Midyat. a | 0.845 | 40.035 | 1.95 | 1.071 |

| One has the chance to meet people from different cultures in Midyat. a | 0.749 | 26.519 | 3.48 | 1.350 |

| There is a community atmosphere in Midyat. a | 0.765 | 29.496 | 3.35 | 1.335 |

| Perceived Economic Impacts (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.895; CR = 0.92; AVE = 0.71) | ||||

| The living standard is sufficient in Midyat. a | 0.827 | 41.693 | 2.46 | 1.005 |

| Job opportunities are sufficient in Midyat. a | 0.897 | 66.454 | 2.05 | 0.983 |

| The infrastructure is sufficient in Midyat. a | 0.885 | 58.825 | 2.00 | 1.095 |

| The economic income of Midyat is sufficient. a | 0.884 | 53.875 | 2.16 | 1.092 |

| Land property/house prices of Midyat are reasonable. a | 0.703 | 17.935 | 1.86 | 1.138 |

| Perceived Environmental Impacts (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.706; CR = 0.78; AVE = 0.48) | ||||

| Midyat is crowded. a | 0.722 | 4.012 | 2.91 | 1.112 |

| Traffic congestions occur in Midyat. a | 0.715 | 6.036 | 2.63 | 1.218 |

| Noise levels of Midyat are high. a | 0.650 | 4.170 | 2.53 | 1.152 |

| There is environmental pollution in Midyat. a | 0.671 | 4.824 | 3.10 | 1.337 |

| Support for Sustainable Tourism (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.870; CR = 0.92; AVE = 0.79) | ||||

| Tourism must be developed, focusing on cultural and historical attractions. a | 0.910 | 32.780 | 4.36 | 0.910 |

| I am happy and proud that there are tourists coming to see what the city has to offer. a | 0.849 | 43.506 | 4.14 | 1.048 |

| I would want to see more tourism development in the city. a | 0.914 | 65.228 | 4.47 | 0.834 |

| Second Order | ||||

| Residents’ Place Image (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.877; CR = 0.90; AVE = 0.40) | ||||

| Social Attributes | 0.486 | 10.815 | ||

| Transport Attributes | 0.738 | 22.881 | ||

| Government Service Attributes | 0.882 | 63.400 | ||

| Shopping | 0.794 | 33.340 | ||

| Government Service Attributes | Perceived Economic Impacts | Perceived Environmental Impacts s | Perceived Socio-Cultural Impacts | Shopping | Social Attributes | Support for Sustainable Tourism | Transport Attributes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government Service Attributes (RPI) | 0.824 | |||||||

| Perceived Economic Impacts | 0.589 | 0.842 | ||||||

| Perceived Environmental Impacts | 0.164 | 0.190 | 0.690 | |||||

| Perceived Socio-cultural Impacts | 0.563 | 0.660 | 0.305 | 0.780 | ||||

| Shopping (RPI) | 0.571 | 0.524 | 0.217 | 0.562 | 0.822 | |||

| Social Attributes (RPI) | 0.262 | 0.231 | 0.147 | 0.319 | 0.285 | 0.859 | ||

| Support for Sustainable Tourism | 0.204 | 0.069 | 0.327 | 0.244 | 0.249 | 0.176 | 0.891 | |

| Transport Attributes (RPI) | 0.606 | 0.507 | −0.043 | 0.397 | 0.353 | 0.232 | 0.161 | 0.866 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 supported | RPI → PSCI | 0.640 | 0.641 | 0.036 | 17.655 | 0.000 |

| H2 supported | RPI → PECI | 0.652 | 0.653 | 0.037 | 17.850 | 0.000 |

| H3 not supported | RPI → PENI | 0.172 | 0.171 | 0.102 | 1.693 | 0.091 |

| H4 supported | PSCI → SUST | 0.263 | 0.268 | 0.073 | 3.585 | 0.000 |

| H5 not supported | PECI → SUST | −0.157 | −0.156 | 0.073 | 2.150 | 0.032 |

| H6 supported | PENI → SUST | 0.277 | 0.277 | 0.057 | 4.828 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uslu, A.; Erul, E.; Santos, J.A.C.; Obradović, S.; Custódio Santos, M. Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: An Empirical Study in Midyat, Turkey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310013

Uslu A, Erul E, Santos JAC, Obradović S, Custódio Santos M. Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: An Empirical Study in Midyat, Turkey. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310013

Chicago/Turabian StyleUslu, Abdullah, Emrullah Erul, José António C. Santos, Sanja Obradović, and Margarida Custódio Santos. 2023. "Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: An Empirical Study in Midyat, Turkey" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310013

APA StyleUslu, A., Erul, E., Santos, J. A. C., Obradović, S., & Custódio Santos, M. (2023). Determinants of Residents’ Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: An Empirical Study in Midyat, Turkey. Sustainability, 15(13), 10013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310013