Harnessing Big Data Analytics to Accelerate Innovation: An Empirical Study on Sport-Based Entrepreneurs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Study Hypotheses

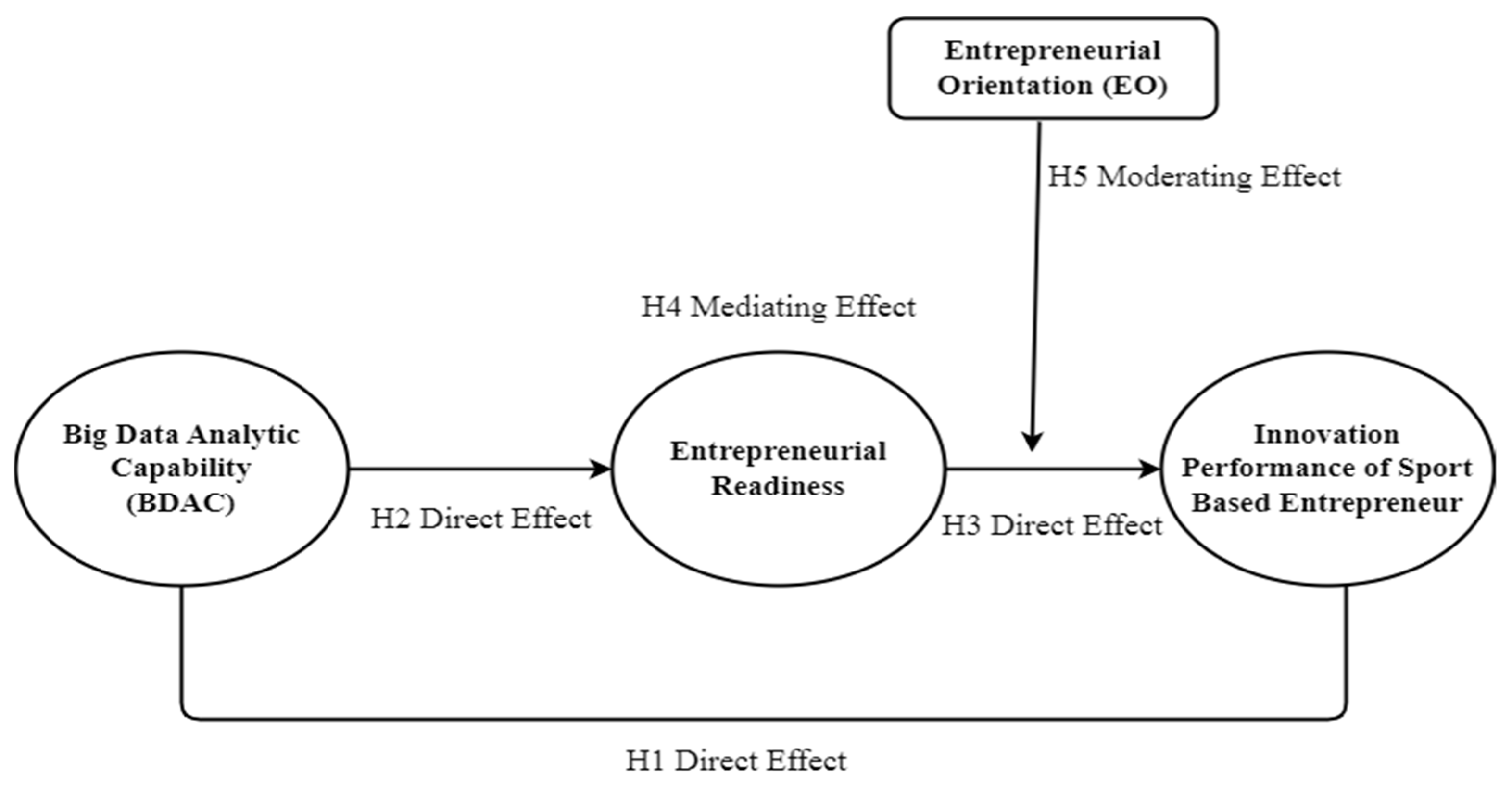

2.1. Big Data Analytic Capability and Innovation Performance

2.2. Big Data Analytic Capability and Entrepreneurial Readiness

2.3. Mediation of Entrepreneurial Readiness

2.4. Moderating Role of EO

2.5. Anchored Instruction Theory and Study Framework

2.6. Methodology

2.7. Study Measures

3. Data Analysis and Results

3.1. Constructs’ Reliability and Validity

3.2. Correlation Statistics

3.3. Hypotheses Testing

3.4. Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Entrepreneurial Readiness (ER)—Six items

- I understand that specific changes may improve outcomes.

- I am willing to try new ideas, and it is easy to change procedures to meet new conditions.

- I express my concerns about changes.

- When changes are necessary, I have a clear plan for implementing these changes.

- I always explore evidence-based practice techniques.

- I adapt quickly when there is a need to shift focus to accommodate program changes.

- Innovation Performance (IP)—11 items

- I try to provide products and services that focus on core functionality rather than on additional functionality.

- I try to regularly search for new solutions that offer ease of use of products/services.

- I try to regularly improve the durability of the products/services.

- I try to introduce new solutions that offer good and cheap products/services.

- I try to significantly reduce cost in the operational process.

- I try to significantly reduce the final price of the products/services.

- I try to open new domestic target groups.

- I try for innovation in project development.

- I try to work on innovation projects.

- I try for average cost per innovation project.

- I try for a global degree of satisfaction with innovation project efficiency.

- Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO)—Nine items

- I have a strong emphasis on technological leadership and innovation.

- In the last three years, I marketed various new product lines or services.

- In my business, changes in product or service lines have been quite dramatic.

- I initiated actions to respond to the competitors.

- I am the first to introduce new product or services.

- I preferred a competitive ‘undo-the-competitors’ posture.

- I had a strong proclivity for high-risk projects.

- I believed that owing to the nature of the environment, wide-ranging acts are necessary.

- I adopted a bold, aggressive posture to maximize the innovation activities.

- Big Data Analytic Capabilities (BDACs)—10 items

- Access very large, unstructured or fast-moving data for analysis.

- Integrate data from multiple internal sources into a data warehouse or mart for easy access.

- Integrate external data with internal to facilitate high-value analysis of our business environment.

- Explore or adopt parallel computing approaches (e.g., Hadoop) to big data processing.

- Explore or adopt different data visualization tools.

- Explore or adopted cloud-based services for processing data and performing analytics.

- Explore or adopt open-source software for big data analytics.

- Explore or adopt new forms of databases for storing data.

- Base my decisions on data rather than on instinct.

- Override my own intuition when data contradict my viewpoints.

References

- Malik, P.K.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Das, P.K. Village 4.0: Digitalization of village with smart internet of things technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 165, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.; Demi, S.; Magrini, A.; Marzi, G.; Papa, A. Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on business model innovation: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; He, W. Research on opinion polarization by big data analytics capabilities in online social networks. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Sport-based entrepreneurship: Towards a new theory of entrepreneurship and sport management. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesämaa, O.; Zwikael, O.; Hair, J., Jr.; Huemann, M. Publishing quantitative papers with rigor and transparency. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J.; Scott, S.V. 10 sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 433–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alrawad, M.; Abdo, A.A.K.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Ibrahim, N.; Saad, M. Factors influencing the adoption of big data analytics in the digital transformation era: Case study of Jordanian SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.; Court, D. Making advanced analytics work for you. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 90, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L.T.; Robin, R.; Stone, M.; Aravopoulou, D.E. Adoption of big data technology for innovation in B2B marketing. J. Bus.-Bus. Mark. 2019, 26, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Davenport, T.H.; Patil, D.J.; Barton, D. Big data: The management revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 90, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gobble, M.M. Big data: The next big thing in innovation. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2013, 56, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V.S.; Costley, A.E.; Wan, B.N.; Garofalo, A.M.; Leuer, J.A. Evaluation of CFETR as a fusion nuclear science facility using multiple system codes. Nucl. Fusion 2015, 55, 023017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Galley, M.; Brockett, C.; Spithourakis, G.P.; Gao, J.; Dolan, B. A persona-based neural conversation model. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.06155. [Google Scholar]

- Pounder, P. Examining interconnectivity of entrepreneurship, innovation and sports policy framework. J. Entrep. Public Policy 2019, 8, 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Manyika, J.; Chui, M.; Brown, B.; Bughin, J.; Dobbs, R.; Roxburgh, C.; Byers, A.H. Big Data: The Next Frontier for Innovation, Competition (5, 6) and Productivity; Technical report; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, M.I.; Shuib, L.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Big data adoption: State of the art and research challenges. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehning, B.; Richardson, V.J. Returns on investments in information technology: A research synthesis. J. Inf. Syst. 2002, 16, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, N.; Kraemer, K.; Gurbaxani, V. Information technology and organizational performance: An integrative model of IT business value. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 283–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davenport, T. Big Data at Work: Dispelling the Myths, Uncovering the Opportunities; Harvard Business Review Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bapst, V.; Heess, N.; Mnih, V.; Munos, R.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; de Freitas, N. Sample efficient actor-critic with experience replay. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01224. [Google Scholar]

- Wamba, S.F.; Akter, S.; Edwards, A.; Chopin, G.; Gnanzou, D. How ‘big data’ can make big impact: Findings from a systematic review and a longitudinal case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 165, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Social CRM capabilities and readiness: Findings from Greek tourism firms. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeck, M.; Shockley, R.; Smart, J.; Romero, D.; Tufano, P. Analytics: Eluso de big data enelmundo real. In IBM Institute for Business Value; Informe ejecutivo; Escuela de Negocios Saïd en la Universidad de Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, R. The measurement of innovation performance in the firm: An overview. Res. Policy 1990, 19, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. Big data analysis adaptation and enterprises’ competitive advantages: The perspective of dynamic capability and resource-based theories. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiron, D. Organizational alignment is key to big data success. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2013, 54, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, G.; Polimeno, G.; Solazzo, G.; Passiante, G. A multi-dimension framework for value creation through big data. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 90, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbola, S.A. Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and startup success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miake-Lye, I.M.; Delevan, D.M.; Ganz, D.A.; Mittman, B.S.; Finley, E.P. Unpacking organizational readiness for change: An updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Najran, N.; Dahanayake, A. A requirements specification framework for big data collection and capture. In East European Conference on Advances in Databases and Information Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Olszak, C.M.; Mach-Król, M. A conceptual framework for assessing an organization’s readiness to adopt big data. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, N.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M. Bigdatainan. HR context: Exploring organizational change readiness, employee attitudes and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haddad, A.; Ameen, A.A.; Mukred, M. The impact of intention of use on the success of big data adoption via organization readiness factor. Int. J. Manag. Hum. Sci. (IJMHS) 2018, 2, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Klievink, B.; Romijn, B.J.; Cunningham, S.; de Bruijn, H. Big data in the public sector: Uncertainties and readiness. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 19, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatzoglou, P.D.; Michailidou, V.N. A survey on the 3D printing technology readiness to use. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2585–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, M.; Ramezani, J. A model to evaluate the organizational readiness for big data adoption. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2020, 15, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onukwugha, E.; Jain, R.; Albarmawi, H. Evidence generation using big data: Challenges and opportunities. Decis. Mak. A World Comp. Eff. Res. 2017, 4, 253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ur Rehman, M.H.; Chang, V.; Batool, A.; Wah, T.Y. Big data reduction framework for value creation in sustainable enterprises. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goss, R.G.; Veeramuthu, K. Heading towards big data building a better data warehouse for more data, more speed, and more usersv. In Proceedings of the ASMC 2013 SEMI Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA, 14–16 May 2013; pp. 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Banjongprasert, J. An Assessment of Change-Readiness Capabilities and Service Innovation Readiness and Innovation Performance: Empirical Evidence from MICE Venues. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 11, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Papastathopoulos, A. Organizational readiness for digital financial innovation and financial resilience. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 243, 108326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, J.; Mirchandani, D.; Madan, M.; Gunasekaran, A. Successful implementation of ERP projects: Evidence from two case studies. Int. J. Prod. Rconomics 2002, 75, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrasbi, N.; Paré, G. Inside the Black Box: Investigating the Link between Organizational Readiness and IT Implementation Success. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kasasih, K.; Wibowo, W.; Saparuddin, S. The influence of ambidextrous organization and authentic followership on innovative performance: The mediating role of change readiness. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemaghaei, M.; Calic, G. Assessing the impact of big data on firm innovation performance: Big data is not always better data. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmairat, M.A. Big data analytics capabilities, SC innovation, customer readiness, and digital SC performance: The mediation role of SC resilience. Int. J. Adv. Oper. Manag. 2023, 15, 82–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Z.; Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Yasir, M. Nexus of digital organizational culture, capabilities, organizational readiness, and innovation: Investigation of SMEs operating in the digital economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Alsyouf, A.; Alrawad, M.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Saad, M.; Ali, R.A. Antecedents of Big Data Analytic Adoption and Impacts on Performance: Contingent Effect. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Lumpkin, G.T. Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhoushi, M.; Sadati, A.; Delavari, H.; Mehdivand, M.; Mihandost, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation performance: The mediating role of knowledge management. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Freixanet, J.; Braojos, J.; Rialp-Criado, A.; Rialp-Criado, J. Does international entrepreneurial orientation foster innovation performance? The mediating role of social media and open innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2021, 22, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ma, X.; Yu, H. Entrepreneurial orientation, interaction orientation, and innovation performance: A model of moderated mediation. Sage Open 2019, 9, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jin, J. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation performance: Roles of strategic HRM and technical turbulence. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 53, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Nasir, M.H.; Yousaf, Z.; Khattak, A.; Yasir, M.; Javed, A.; Shirazi, S.H. Innovation performance in digital economy: Does digital platform capability, improvisation capability and organizational readiness really matter? Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.S.A.; Zaidi, S.S.Z. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Intensity: Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2021, 3, 202–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bransford, J.D.; Sherwood, R.D.; Hasselbring, T.S.; Kinzer, C.K.; Williams, S.M. Anchored instruction: Why we need it and how technology can help. Cogn. Educ. Multimed. Explor. Ideas High Technol. 1990, 12, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Riyanto, R.; Amin, M.; Suwono, H.; Lestari, U. The new face of digital books in genetic learning: A preliminary development study for students’ critical thinking. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucchi, D.; Buganza, T. Data-driven innovation: Switching the perspective on Big Data. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovič, A.; Hackney, R.; Tassabehji, R.; Castelli, M. The impact of big data analytics on firms’ high value business performance. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Saad, M.; Ibrahim, N. Drivers and impact of big data analytic adoption in the retail industry: A quantitative investigation applying structural equation modeling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Boura, M.; Lekakos, G.; Krogstie, J. Big data analytics capabilities and innovation: The mediating role of dynamic capabilities and moderating effect of the environment. Br. J. Manag. 2019, 30, 272–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsaeed, R.H.; Grigorescu, A.; Yousaf, Z.; Condrea, E.; Nassani, A.A. Leading Role of Big Data Analytic Capability in Innovation Performance: Role of Organizational Readiness and Digital Orientation. Systems 2023, 11, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Shin, B.; Kwon, O. Investigating the value of socio materialism in conceptualizing IT capability of a firm. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 327–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Somers, T.M.; Gupta, Y.P. Impact of information technology management practices on customer service. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 17, 125–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claiborne, N.; Auerbach, C.; Lawrence, C.; Schudrich, W.Z. Organizational change: The role of climate and job satisfaction in child welfare workers’ perception of readiness for change. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Assessing the impact of organizational learning capability on product innovation performance: An empirical test. Technovation 2008, 28, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, O.N.; Strenge, M. Entrepreneurial orientation as a driver of brokerage in external networks: Exploring the effects of risk taking, proactivity, and innovativeness. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Alpha | FL | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDAC | 10 | 0.80 | 0.73–0.94 | 0.81 | 0.68 |

| Entrepreneurial readiness | 07 | 0.81 | 0.76–0.90 | 0.83 | 0.74 |

| Innovation performance | 04 | 0.86 | 0.71–0.95 | 0.85 | 0.71 |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | 06 | 0.79 | 0.74–0.92 | 0.80 | 0.69 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1 | |||||||

| Respondent age | 31 | --- | 0.08 | 1 | ||||||

| Work experience | 2.5 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1 | |||||

| Education level | 2.6 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1 | ||||

| BDAC | 3.5 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.10 * | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1 | |||

| Entrepreneurial readiness | 3.7 | 0.94 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.37 ** | 1 | ||

| Entrepreneurial orientation | 3.9 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.26 ** | 0.30 ** | 1 | |

| Innovation performance | 3.7 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.31 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.22 ** | 1 |

| Specification | Estimate | LL | UP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct impact | |||

| BDAC → IP | 0.27 * | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| BDAC → Entrepreneurial readiness | 0.39 * | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| Entrepreneurial readiness → IP | 0.32 * | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| Specification | Estimate | LL | UP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized direct impact | |||

| BDAC → IP | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.27 |

| BDAC → Entrepreneurial readiness | 0.39 * | 0.39 | 0.58 |

| Entrepreneurial readiness → IP | 0.32 * | 0.19 | 0.50 |

| Standardized indirect effects | |||

| BDAC → Entrepreneurial readiness → IP | 0.21 * | 0.07 | 0.27 |

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderation of EO | |||

| Entrepreneurial readiness | 0.30 ** | 0.34 ** | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.27 ** | 0.32 ** | |

| Entrepreneurial readiness × Entrepreneurial orientation | 0.25 ** | ||

| R2 | 0.009 | 0.191 | 0.198 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.003 | 0.159 | 0.175 |

| ∆R2 | 0.007 | 0.163 | 0.028 |

| ∆F | 4.172 | 79.63 | 17.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Binsaeed, R.H.; Grigorescu, A.; Yousaf, Z.; Radu, F.; Nassani, A.A.; Tabirca, A.I. Harnessing Big Data Analytics to Accelerate Innovation: An Empirical Study on Sport-Based Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310090

Binsaeed RH, Grigorescu A, Yousaf Z, Radu F, Nassani AA, Tabirca AI. Harnessing Big Data Analytics to Accelerate Innovation: An Empirical Study on Sport-Based Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310090

Chicago/Turabian StyleBinsaeed, Rima H., Adriana Grigorescu, Zahid Yousaf, Florin Radu, Abdelmohsen A. Nassani, and Alina Iuliana Tabirca. 2023. "Harnessing Big Data Analytics to Accelerate Innovation: An Empirical Study on Sport-Based Entrepreneurs" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310090

APA StyleBinsaeed, R. H., Grigorescu, A., Yousaf, Z., Radu, F., Nassani, A. A., & Tabirca, A. I. (2023). Harnessing Big Data Analytics to Accelerate Innovation: An Empirical Study on Sport-Based Entrepreneurs. Sustainability, 15(13), 10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310090