The Sustainable Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes Link: An HR Process Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Model

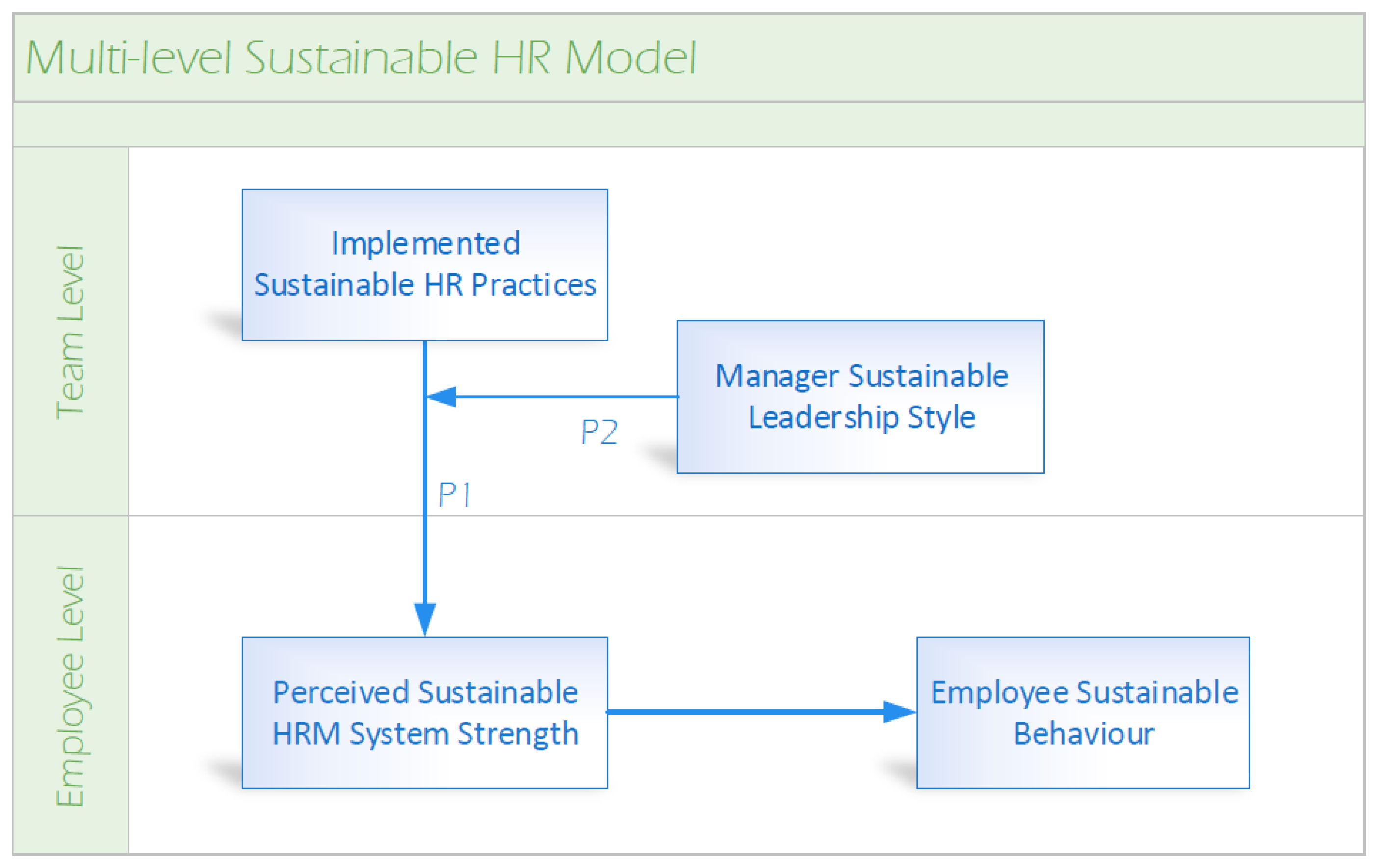

3.1. A Sustainable HR Process Model

3.1.1. Implemented Sustainable HR Practices

3.1.2. Perceived Sustainable HRM System Strength

3.1.3. Sustainable Employee Behaviour

3.1.4. Sustainable Leadership Style

3.2. Perceived HRM System Strength as an Alternative to Employee Perceptions

3.2.1. The Effect of Perceived Sustainable HRM System Strength

3.2.2. The Impact of Sustainable Leadership Style

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, W.K.; Besharov, M.L.; Wessels, A.K.; Chertok, M. A Paradoxical Leadership Model for Social Entrepreneurs: Challenges, Leadership Skills, and Pedagogical Tools for Managing Social and Commercial Demands. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2012, 11, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, F.; Etzion, D.; Gehman, J. Tackling Grand Challenges Pragmatically: Robust Action Revisited. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. The Brundtland Report: “Our Common Future”; World Commission on Environment and Development: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Fawehinmi, O.O. Green Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review from 2007 to 2019. Benchmarking 2020, 27, 2005–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Vaiman, V.; Sanders, K. Strategic Human Resource Management in the Era of Environmental Disruptions. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology From Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on Sustainability and HRM: A Comparative Study of Sustainability Reporting Practices by the World’s Largest Companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Genari, D. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Human Resource Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green Human Resource Practices and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Roles of Collective Green Crafting and Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidner, S.; Baden, D.; Ashleigh, M.J. Green (Environmental) HRM: Aligning Ideals with Appropriate Practices. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamdamov, A.; Tang, Z.; Hussain, M.A. Unpacking Parallel Mediation Processes between Green HRM Practices and Sustainable Environmental Performance: Evidence from Uzbekistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, E.; Akbaba, M.; Yakut, E.; Çetinel, M.H.; Pasli, M.M. The Mediating Effect of Green Human Resources Management on the Relationship between Organizational Sustainability and Innovative Behavior: An Application in Turkey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, M.; Taha, B.; Saleh, Y.; Alsayed, M.; Assaf, R.; Hassen, M.B.; Alshaibani, E.; Bakir, A.; Tunsi, W. Green Innovation as a Mediator between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Sustainable Performance in Palestinian Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Moreno, E.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.; Martinez-Del-Rio, J. Environmental Human Resource Management and Competitive Advantage Environmental Human Resource Management. Manag. Res. 2012, 10, 1536–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macassa, G.; Tomaselli, G. Socially Responsible Human Resources Management and Stakeholders’ Health Promotion: A Conceptual Paper. South East. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. The Link between Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Intellectual Capital. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lee, B.Y.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, S.; Liu, Z. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Performance: The Roles of Perceived External Prestige and Employee Human Resource Attributions. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Carrion, R.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M. Sustainable Human Resource Management and Employee Engagement: A Holistic Assessment Instrument. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.F.; Romi, A.M.; Sanchez, J.M. The Influence of Corporate Sustainability Officers on Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1065–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Ramos, L.; Huertas-Valdivia, I.; García-Muiña, F.E. Exploring the Cornerstones of Green, Sustainable and Socially Responsible Human Resource Management. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 44, 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.; Hu, J. Unlocking the Potential of Sustainable Human Resource Management: The Role of Managers. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2022, 2022, 16245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M.; Aust, I. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Perception: The Influence of Manager and Line Managers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; den Hartog, D.N.; Boselie, P.; Paauwe, J. The Relationship between Perceptions of HR Practices and Employee Outcomes: Examining the Role of Person-Organisation and Person-Job Fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and When Does Socially Responsible HRM Affect Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors Toward the Environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, R.A.; Noonan, K.A. Human Resource Practices as Communications and the Psychological Contract. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1994, 33, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Sustainable Human Resource Management: Six Defining Characteristics. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Vanhala, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management with Salience of Stakeholders: A Top Management Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Boselie, P.; Paauwe, J. Performance Management: A Model and Research Agenda. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 53, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.; Lochan Dhar, R. Green Competencies: Construct Development and Measurement Validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.-L.; Lin, H.-H.; Yang, T.-L.; Elrayah, M.; Semlali, Y. Sustainable Total Reward Strategies for Talented Employees’ Sustainable Performance, Satisfaction, and Motivation: Evidence from the Educational Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraibar-Diez, E.; Odriozola, M.D.; Fernández Sánchez, J.L. Sustainable Compensation Policies and Its Effect on Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvnjak, B.; Kohont, A. The Role of Sustainable HRM in Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond Strategic Human Resource Management: Is Sustainable Human Resource Management the next Approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, I.; Matthews, B.; Muller-Camen, M. Common Good HRM: A Paradigm Shift in Sustainable HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P. Mutuality in the Management of Human Resources: Assessing the Quality of Alignment in Employment Relationships. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2013, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Seo, J. The Greening of Strategic HRM Scholarship. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Effects of Green HRM and CEO Ethical Leadership on Organizations’ Environmental Performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 52, 961–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An Employee-Level Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Halim, H.A. How Does Sustainable Leadership Influence Sustainable Performance? Empirical Evidence From Selected ASEAN Countries. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, R.; van der Heijden, B.; Peters, P.; Kraus-Hoogeveen, S.; Heres, L. More Roads Lead to Rome. HR Configurations and Employee Sustainability Outcomes in Public Sector Organizations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. On the Importance of Sustainable Human Resource Management for the Adoption of Sustainable Development Goals. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Gupta, S. Examining the Effect of Green Human Capital Availability in Adoption of Reverse Logistics and Remanufacturing Operations Performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 1097–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, N.; Cvetković, V.; Zečević, M. Human Resource Management in Environmental Protection in Serbia. Bull. Serbian Geogr. Soc. 2020, 100, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Bowen, D. Reflections on the 2014 Decade Award: Is There Strength in the Construct of HR System Strength? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Wright, P.M. Variability at Multiple Levels of Analysis: Implications for Strategic Human Resource Management. In The People Make the Place; Smith, D.B., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 225–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kim, S.; Rafferty, A.; Sanders, K. Employee Perceptions of HR Practices: A Critical Review and Future Directions. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 128–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Yang, H.; Li, X. Quality Enhancement or Cost Reduction? The Influence of High-Performance Work Systems and Power Distance Orientation on Employee Human Resource Attributions. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 32, 4463–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Yang, H.; Patel, C. Handbook on HR Process Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781839100079. [Google Scholar]

- Bos-Nehles, A.; Van Riemsdijk, M.J.; Kees Looise, J. Employee Perceptions of Line Management Performance: Applying the AMO Theory to Explain the Effectiveness of Line Managers’ HRM Implementation. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Boon, C.; Verburg, R.M.; Croon, M.A. HRM, Communication, Satisfaction, and Perceived Performance: A Cross-Level Test. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1637–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.; Hutchinson, S. Front-Line Managers as Agents in the HRM-Performance Causal Chain: Theory, Analysis and Evidence. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2007, 17, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E.; Sanders, K.; Rodrigues, R.; Oliveira, T. Signalling Theory as a Framework for Analysing Human Resource Management Processes and Integrating Human Resource Attribution Theories: A Conceptual Analysis and Empirical Exploration. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, D.D.; Connelly, B.L.; Ketchen, D.J.; Shannon, L.M. Signalling Theory and Equilibrium in Strategic Management Research: An Assessment and a Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 1334–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM-Firm Performance Linkages: The Role of the “Strength” of the HRM System. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee Attributions of the “Why” of HR Practices: Their Effects on Employee Attitudes and Behaviors, and Customer Satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijer, S.; Peccei, R.; van Veldhoven, M.; Paauwe, J. The Turn to Employees in the Measurement of Human Resource Practices: A Critical Review and Proposed Way Forward. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeeren, B.; Kuipers, B.; Steijn, B. Does Leadership Style Make a Difference? Linking HRM, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Performance. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2014, 34, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A. Encouraging Innovative Environmental Actions: What Companies and Managers Must Do. J. World Bus. 2002, 37, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensen, D.S.; Ellen, B.P.; Wang, G.; Ferris, G.R. Putting the “Management” Back in Human Resource Management: A Review and Agenda for Future Research. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 2387–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katou, A.A.; Budhwar, P.S.; Patel, C. Content vs. Process in the Hrm-Performance Relationship: An Empirical Examination. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Shipton, H.; Gomes, J.F.S. Guest Editors’ Introduction: Is the HRM Process Important? Past, Current and Future Challenges. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Hu, J.; Liu, S.; Lepak, D.P. Understanding Employees’ Perceptions of Human Resource Practices: Effects of Demographic Dissimilarity to Managers and Coworkers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Segers, J.; van Dierendonck, D.; den Hartog, D. Managing People in Organizations: Integrating the Study of HRM and Leadership. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lew, J.Y. Implementing Sustainable Human Resources Practices: Leadership Style Matters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdig, M.A. Sustainability Leadership: Co-Creating a Sustainable Future. J. Chang. Manag. 2007, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M. The Role of Sustainable Human Resource Practices in Influencing Employee Behavior for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.Y.; Farrukh, M.; Raza, A. Green Human Resource Management and Employees Pro-Environmental Behaviours: Examining the Underlying Mechanism. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaga, W.; Kleinaltenkamp, M.; Kashyap, V.; Eggert, A. Advancing Marketing Theory and Practice: Guidelines for Crafting Research Propositions. AMS Rev. 2021, 11, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlesinya, A.; Susomrith, P. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Systematic Review of a Developing Field. J. Glob. Responsib. 2020, 11, 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. A Systematic Review on Green Human Resource Management: Implications for Social Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, A.; Dal Zotto, C. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Paulet, R.; Zheng, L.J. A Literature Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effect on Sustainable HRM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.J.; Johnston, L.H.; Breckon, J.D. Using QSR-NVivo to Facilitate the Development of a Grounded Theory Project: An Account of a Worked Example. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2010, 13, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.A.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S. Relationship between Green Management and Environmental Training in Companies Located in Brazil: A Theoretical Framework and Case Studies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Human Resources Development as an Element of Sustainable HRM–With the Focus on Production Engineers. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human Resource Management and Employee Well-Being: Towards a New Analytic Framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trullen, J.; Bos-Nehles, A.; Valverde, M. From Intended to Actual and Beyond: A Cross-Disciplinary View of (Human Resource Management) Implementation. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 150–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Han, J.H. An Expanded Conceptualization of Line Managers’ Involvement in Human Resource Management. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, C.; Yang, H.; Sanders, K. Introduction to Human Resource Management Process. In Handbook on HR Process Research; Sanders, K., Yang, H., Patel, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. The Triple Bottom Line. 1997, Volume 2. Available online: https://www.johnelkington.com/archive/TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Kainzbauer, A.; Rungruang, P. Science Mapping the Knowledge Base on Sustainable Human Resource Management, 1982–2019. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Bednall, T.C.; Yang, H. HR Strength: Past, Current and Future Research. In Handbook HR Process Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The Processes of Causal Attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.; Zhang, Z.; Talwar, S.; Dhir, A. Do Green Human Resource Management and Self-Efficacy Facilitate Green Creativity? A Study of Luxury Hotels and Resorts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 824–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Y.S.; Garg, R. The Simultaneous Effect of Green Ability-Motivation-Opportunity and Transformational Leadership in Environment Management: The Mediating Role of Green Culture. Benchmarking 2020, 28, 830–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Ababneh, O.M.; Awwad, A.S.; Abu-Haija, A. The Association between Green Human Resources Practices and Employee Engagement with Environmental Initiatives in Hotels: The Moderation Effect of Perceived Transformational Leadership. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 20, 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.F.; Omar, M.K.; Wei, F.; Rasheed, M.I.; Hameed, Z. Green HRM and Psychological Safety: How Transformational Leadership Drives Follower’s Job Satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothfelder, K.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Harrington, R.J. The Impact of Transformational, Transactional and Non-Leadership Styles on Employee Job Satisfaction in the German Hospitality Industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 12, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Momaya, K.S.; Iyer, K.C.C. Bridging the Gaps for Business Growth among Indian Construction Companies. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2021, 11, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.; Sweet, M. The Perceptions of Ethical and Sustainable Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. Leadership for Sustainability: An Evolution of Leadership Ability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.; Holt, R. Servant and Sustainable Leadership: An Analysis in the Manufacturing Environment. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2011, 4, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikand, R.; Saxena, S. Sustainable Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: Exploring Mediating Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility. Vision 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Sustainable Leadership and Entrepreneurship for Corporate Sustainability in Small Enterprises: An Empirical Analysis. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 15, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effects of Key Leadership Determinants on Business Sustainability in Entrepreneurial Enterprises. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JEEE-05-2021-0187/full/html (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G. Sustainable Leadership Practices Driving Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The Impact of High-Performance Human Resource Practices on Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition, 2nd ed.; Mcgraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, K.; Yang, H.; Hewett, R. Looking Back to Move Forward. A 20-Year Overview and an Integrated Model of Human Resource Process Research. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Buckley, R.M., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Wheeler, A.R., Baur, J.E., Eds.; University of Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 2023; Volume 42. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, S.J.; Yu, C. Managing Coworker Assistance Through Organizational Identification. Hum. Perform. 2011, 24, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Goodwin, G.F.; Heffner, T.S.; Salas, E.; Cannon-Bowers, J.A. The Influence of Shared Mental Models on Team Process and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Barthold, M.; Biemann, T.; Alfes, K. Strong Signals in HR Management: How the Configuration and Strength of an HR System Explain the Variability in HR Attributions. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 62, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. Attribution Theory in Social Psychology. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Levine, D., Ed.; Lincoln University Nebraska Press: Lincoln, Nebraska, 1967; pp. 192–238. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W. Arousing Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Synergy Effect of Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership and Green Human Resource Management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 62, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the Theoretical Puzzle of Employees’ Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility: An Integrative Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.L. Managerial Behaviors: Their Relationship to Perceived Organizational Climate in a High-Technology Company. Group Organ. Manag. 1985, 10, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wefald, A.J.; Reichard, R.J.; Serrano, S.A. Fitting Engagement Into a Nomological Network: The Relationship of Engagement to Leadership and Personality. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiewiet, D.J.; Vos, J.F.J.J. Organisational Sustainability: A Case for Formulating a Tailor-Made Definition. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2007, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Sustainable Development: The Colors of Sustainable Leadership in Learning Organization. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable Leadership Practices for Enhancing Business Resilience and Performance. Strategy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Stakeholder Harm Index: A Framework to Review Work Intensification from the Critical HRM Perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, P.; Kira, M.; Shani, A.B.R. What the World Needs Now Is Sustainable Work Systems. In Creating Sustainable Work Systems: Developing Social Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nishii, L.H.; Paluch, R.M. Leaders as HR Sensegivers: Four HR Implementation Behaviors That Create Strong HR Systems. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, R.; Shantz, A.; Mundy, J.; Alfes, K. Attribution Theories in Human Resource Management Research: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, G. Reflections on the 2016 Decade Award: Incorporating Context in Organizational Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.; Fink, D. Sustainable Leadership; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, Z.; Naeem, R.M.; Hassan, M.; Naeem, M.; Nazim, M.; Maqbool, A. How GHRM Is Related to Green Creativity? A Moderated Mediation Model of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Perceived Organizational Support. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Enache-Zegheru, M.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Enhancing Team Performance: A Multilevel Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ullah, K.; Khan, A. The Impact of Green HRM on Green Creativity: Mediating Role of pro-Environmental Behaviors and Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership Style. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 33, 3789–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, H.T.J.; Sanders, K.; Cogin, J.A.; Lin, C.-H. The Pervasiveness And Trajectory Of Methodological Choices: A 20-Year Review Of Human Resource Management Research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 887–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, S.; Conway, N. Employee Experiences of HRM through Daily Affective Events and Their Effects on Perceived Event-Signalled HRM System Strength, Expectancy Perceptions, and Daily Work Engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Yang, H. The HRM Process Approach: The Influence of Employees’ Attribution to Explain the HRM-Performance Relationship. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 55, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Green HRM, Environmental Awareness and Green Behaviors: The Moderating Role of Servant Leadership. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajulu, N.; Daily, B.F. Motivating Employees for Environmental Improvement. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2004, 104, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A. Organizational Support for Employees: Encouraging Creative Ideas for Environmental Sustainability. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Russo, S.; Mascia, D.; Morandi, F. Individual Perceptions of HR Practices, HRM Strength and Appropriateness of Care: A Meso, Multilevel Approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy Bannya, A.; Bainbridge, H.T.J.; Chan-Serafin, S.; Wales, S. HR Practices and Work Relationships: A 20 Year Review of Relational HRM Research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Kusi, M.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Ahmed, F.; Sukamani, D. Influencing Mechanism of Green Human Resource Management and Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Sustainable Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; Gupta, V. (Eds.) Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky, M.; Hackett, R. HRM System Situational Strength in Support of Strategy: Its Effects on Employee Attitudes and Business Unit Performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 34, 1651–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development—ProQuest. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prins, P.; Van Beirendonck, L.; De Vos, A. Sustainable HRM: Bridging Theory and Practice through the ’Respect Openness Continuity (ROC)’-Model. Manag. Rev. 2014, 25, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, J.; Keegan, A.; Aust, I. Line Managers and HRM: A Relational Approach to Paradox. In Research Handbook on Line Managers; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.; Lewis, M. Toward a Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium Model of Organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron-Spektor, E.; Ingram, A.; Keller, J.; Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Microfoundations of Organizational Paradox: The Problem Is How We Think about the Problem. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. A New Theory about Light and Colors. Am. J. Phys. 1993, 61, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Flood, P.C.; Rousseau, D.M.; Morris, T. Line Managers as Paradox Navigators in HRM Implementation: Balancing Consistency and Individual Responsiveness. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, A.; Brandl, J.; Aust, I. Handling Tensions in Human Resource Management: Insights from Paradox Theory. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 33, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, H. Devolving People Management to the Line: How Different Rationales for Devolution Influence People Management Effectiveness. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Gardner, T.M.; Moynihan, L.M.; Allen, M.R. The Relationship between HR Practices and Firm Performance: Examining Causal Order. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 409–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarouk, T.; Trullen, J.; Valverde, M. Special Issue of International Journal of Human Resource Management: It’s Never a Straight Line: Advancing Knowledge on HRM Implementation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2995–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deSter. Creating Sustainable Food & Travel Experiences. Available online: https://www.dester.com/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Howard-Grenville, J.; Davis, G.F.; Dyllick, T.; Miller, C.C.; Thau, S.; Tsui, A.S. Sustainable Development for a Better World: Contributions of Leadership, Management, and Organizations. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elias, A.; Sanders, K.; Hu, J. The Sustainable Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes Link: An HR Process Lens. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310124

Elias A, Sanders K, Hu J. The Sustainable Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes Link: An HR Process Lens. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310124

Chicago/Turabian StyleElias, Aline, Karin Sanders, and Jing Hu. 2023. "The Sustainable Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes Link: An HR Process Lens" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310124

APA StyleElias, A., Sanders, K., & Hu, J. (2023). The Sustainable Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes Link: An HR Process Lens. Sustainability, 15(13), 10124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310124