Sports Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: Focus Groups and Women Sports Managers’ Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

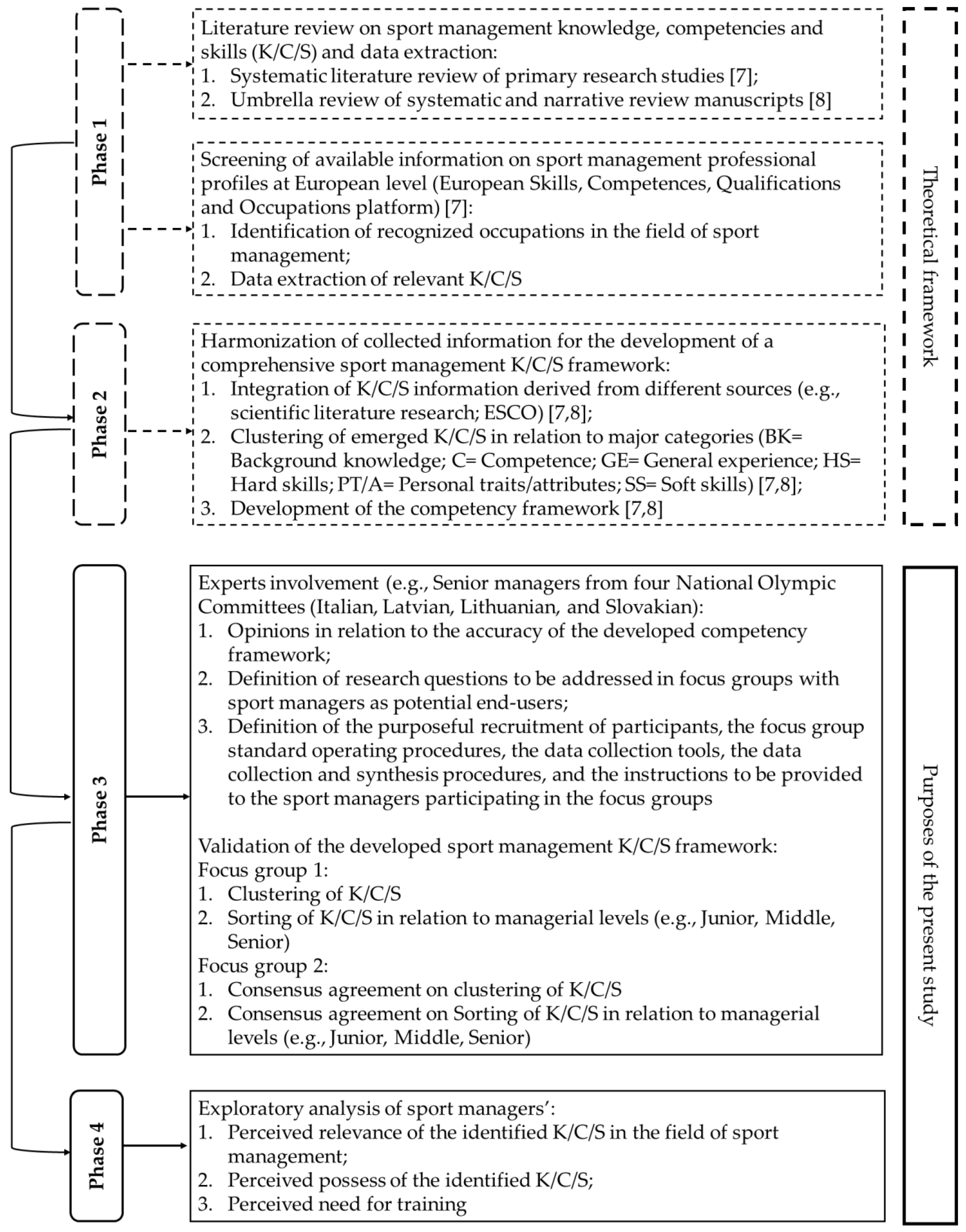

- First, sound evidence-based knowledge of essential and complementary SM K/C/S in relation to both higher education and labor market perspectives was established [7,8]. During this phase, a rigorous literature search and quality assessment of manuscripts published during the past decade (e.g., 2012–2022) and retrieved on three main databases (e.g., EBSCOhost, Scopus, and Google Scholar) was performed, whose outcomes are presented in a systematic literature review on primary research articles [7] and an umbrella review of systematic and narrative review studies [8];

- Second, the collected information has been harmonized to develop a novel comprehensive SM K/C/S framework, including 70 items extracted and harmonized from the included manuscripts in the systematic [7] and umbrella [8] literature reviews and from the ESCO platform (Figure 2 and Appendix A);

- Third, a participatory approach collecting the views of senior sports managers and potential end-users was deemed relevant to test the soundness of the proposed SM K/C/S framework; and

- Fourth, an exploratory analysis of end-users’ perceived relevance, possess, and need for training in relation to the identified K/C/S was envisioned.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- Are sports managers aware of the main five layers of the necessary education and training to operate in the sports industry (e.g., BK = Background, foundational necessary knowledge; C = Competencies for tasks management and performance, modulated by previous personal and working experiences; HS = Hard skills, representing the technical know-how; PT/A = Personal traits/attributes, modulating sports managers’ working behavior and performance; SS = Soft skills, representing intra- and inter-personal non-technical skills enhancing employees’ working relationships), which could guide their education/training choices and behaviors in a lifelong learning perspective?

- Do sports managers perceive the relevance of K/C/S in relation to the three main managerial levels (e.g., Entry, Middle, Senior), which could guide their educational focus and needs in relation to their current career stage? and

- Do sports managers perceive the relevancy, possess, and need of training for the identified K/C/S for their professional career in this field?

2.2. Procedures and Data Collection Tools

2.2.1. International Focus Groups

2.2.2. Survey

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Validation of the Framework: Clustering and Sorting Data Analysis

2.4.2. Rating of the Relevance, Possess, and Need for Training: Survey Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clustering

3.2. Sorting

3.3. Survey

3.3.1. Individual Items

3.3.2. Findings from the Analysis of Clusters Scores

3.3.3. Bivariate Go-Zones

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Label | Items |

| Political skills | Item 1 |

| Analytical skills | Item 2 |

| Business and entrepreneurship | Item 3 |

| Communication skills (written/oral) | Item 4 |

| Conflict management skills | Item 5 |

| Controlling skills | Item 6 |

| Cross-cultural competence | Item 7 |

| Decision Making skills | Item 8 |

| Effective interpersonal communication skills | Item 9 |

| Evaluation skills | Item 10 |

| Event management | Item 11 |

| Facility/operations management | Item 12 |

| Finance and administration | Item 13 |

| Foreign languages | Item 14 |

| Fundraising and grant writing | Item 15 |

| Goal orientation-setting | Item 16 |

| Human resources | Item 17 |

| Information management | Item 18 |

| Leadership skills | Item 19 |

| Legal knowledge and sport law | Item 20 |

| Marketing | Item 21 |

| Meetings management | Item 22 |

| Networking | Item 23 |

| Planning/organization/coordination skills | Item 24 |

| Project management | Item 25 |

| Problem solving | Item 26 |

| Research skills | Item 27 |

| Risk management | Item 28 |

| Safety/security/health management | Item 29 |

| Social skills/People skills | Item 30 |

| Sponsorship management | Item 31 |

| Stakeholder management | Item 32 |

| Strategic management and ability to manage change | Item 33 |

| Tasks and resources management | Item 34 |

| Technological/digital/social media skills | Item 35 |

| Volunteer management | Item 36 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility | Item 37 |

| History of sport and sport philosophy | Item 38 |

| Ability to deal with pressure/stress | Item 39 |

| Accountability/responsibility | Item 40 |

| Adaptability/flexibility skills | Item 41 |

| Appropriate working behavior/professionalism | Item 42 |

| Career awareness and planning | Item 43 |

| Creativity and innovation | Item 44 |

| Critical Thinking | Item 45 |

| Education, qualification, academic achievement | Item 46 |

| Emotional and interpersonal intelligence | Item 47 |

| Ethical behavior/integrity | Item 48 |

| General previous work-related experience | Item 49 |

| Initiative/proactivity | Item 50 |

| Knowledge transfer to practice | Item 51 |

| Learning (skills and will) | Item 52 |

| Motivation/enthusiasm/Passion | Item 53 |

| Personal management | Item 54 |

| Practical intelligence | Item 55 |

| Respect of hierarchies, role boundaries, and responsibilities | Item 56 |

| Sport participation/involvement/knowledge | Item 57 |

| Teamwork | Item 58 |

| Time management | Item 59 |

| Transferable skills | Item 60 |

| Working autonomy | Item 61 |

| Constant availability | Item 62 |

| Delegation skills | Item 63 |

| Negotiation skills | Item 64 |

| Maturity | Item 65 |

| Relatability | Item 66 |

| Resilience/perseverance | Item 67 |

| Self-confidence | Item 68 |

| Social judgment skills | Item 69 |

| Social self-efficacy | Item 70 |

References

- Cunningham, G.B.; Fink, J.S.; Zhang, J.J. The Distinctiveness of Sport Management Theory and Research. Kinesiol. Rev. 2021, 10, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifried, C.S. A Review of the North American Society for Sport Management and Its Foundational Core: Mapping the Influence of “History”. J. Manag. Hist. 2014, 20, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Association for Sport Management. Available online: https://wasmorg.com/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Seifried, C.; Agyemang, K.; Walker, N.; Soebbing, B. Sport Management and Business Schools: A Growing Partnership in a Changing Higher Education Environment. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutović, T.; Relja, R.; Popović, T. The Constitution of Profession in a Sociological Sense: An Example of Sports Management. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciomaga, B. Sport Management: A Bibliometric Study on Central Themes and Trends. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2013, 13, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Relevant Sport Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: An Umbrella Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, W. The Role of Sport in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. UN Chron. 2016, 53, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Resolution Adopted on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Jalonen, H.; Tuominen, S.; Ryömä, A.; Haltia, J.; Nenonen, J.; Kuikka, A. How Does Value Creation Manifest Itself in the Nexus of Sport and Business? A Systematic Literature Review. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 103–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C.; Popp, B. The Sport Value Framework—A New Fundamental Logic for Analyses in Sport Management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication on a European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Pillar of Social Rights. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ce37482a-d0ca-11e7-a7df-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-62666461 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Alexandris Polomarkakis, K. The European Pillar of Social Rights and the Quest for EU Social Sustainability. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2020, 29, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Statistics on Young People Neither in Employment nor in Education or Training; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ströbel, T.; David Ridpath, B.; Woratschek, H.; O’Reilly, N.; Buser, M.; Pfahl, M. Co-Branding through an International Double Degree Program: A Single Case Study in Sport Management Education. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, D.; Bravo, G.; Lee, C. Careers in Collegiate Athletic Administration: Hiring Criteria and Skills Needed for Success. Manag. Leis. 2013, 18, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Won, D.; Shonk, D.J. Entry-Level Employment in Intercollegiate Athletic Departments: Non-Readily Observables and Readily Observable Attributes of Job Candidates. J. Sport Adm. Superv. 2012, 4, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Nová, J. New Directions for Professional Preparation—A Competency-Based Model for Training Sport Management Personnel. In Sport Governance and Operations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksteen, E.; Malan, D.D.J.; Lotriet, R. Management Competencies of Sport Club Managers in the North West Province. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2013, 19, 928–936. [Google Scholar]

- Jinkins, L. Innovation Opportunities in Sport Management: Agile Business, Flash Teams, and Human-Centered Design. Sport. Innov. J. 2021, 2, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schepper, J.; Sotiriadou, P. A Framework for Critical Reflection in Sport Management Education and Graduate Employability. Ann. Leis. Res. 2018, 21, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schepper, J.; Sotiriadou, P.; Hill, B. The Role of Critical Reflection as an Employability Skill in Sport Management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2021, 21, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luca, J.R.; Braunstein-Minkove, J. An Evaluation of Sport Management Student Preparedness: Recommendations for Adapting Curriculum to Meet Industry Needs. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2016, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitskari, E.; Goudas, M.; Tsalouchou, E.; Michalopoulou, M. Employers’ Expectations of the Employability Skills Needed in the Sport and Recreation Environment. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, O.; Adam, S.; Hovemann, G. Aligning Competence-Oriented Qualifications in Sport Management Higher Education with Industry Requirements: An Importance–Performance Analysis. Ind. High. Educ. 2022, 36, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, O.; Adam, S.; García-Unanue, J.; Hovemann, G.; Skirstad, B.; Strittmatter, A.M. Internationalization of the Sport Management Labor Market and Curriculum Perspectives: Insights from Germany, Norway, and Spain. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Skills, Qualifications and Jobs in the EU: The Making of a Perfect Match? Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/3072_en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Europass. Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning. Available online: https://europa.eu/europass/en/validation-non-formal-and-informal-learning (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Skills, Competencies, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO). Available online: https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Gender in Sport. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-sport (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Commission. Towards More Gender Equality in Sport—Recommendations and Action Plan from the High Level Group on Gender Equality in Sport. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/684ab3af-9f57-11ec-83e1-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Factsheet—Women in the Olympic Movement. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Documents/Olympic-Movement/Factsheets/Women-in-the-Olympic-Movement.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Gender Equality Review Project. Available online: https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/Promote-Olympism/Women-And-Sport/Boxes%20CTA/IOC-Gender-Equality-Report-March-2018.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Costa, C.; Miragaia, D.A.M. A Systematic Review of Women’s Entrepreneurship in the Sports Industry. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 37, 988–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megheirkouni, M.; Roomi, M.A. Women’s Leadership Development in Sport Settings: Factors Influencing the Transformational Learning Experience of Female Managers. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Motion for a European Parliament Resolution on EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2021-0318_EN.html (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- European Commission. White Paper on Sport. Available online: https://www.aop.pt/upload/tb_content/320160419151552/35716314642829/whitepaperfullen.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- New Miracle Project. Women’s Empowerment in Sport and Physical Education Industry. Available online: http://www.newmiracle.simplex.lt (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Miragaia, D.A.M.; Soares, J.A.P. Higher Education in Sport Management: A Systematic Review of Research Topics and Trends. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.; Batista, P.; Carvalho, M.J. Framing Sport Managers’ Profile: A Systematic Review of the Literature between 2000 and 2019. Sport TK-EuroAmerican J. Sport Sci. 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genzuk, M. A Synthesis of Ethnographic Research Methods; Center for Multilingual, Multicultural Research: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K.R. Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities within Sport and Exercise Psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreal, R. Online Education Using Learning Objects; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Lai, S.A.; Armstrong, C.G.; Bunds, K.S. Sport Management Internship Quality and the Development of Political Skill: A Conceptual Model. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2016, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.S.Y.; Kim, C. Construction of Sports Business Professional Competence Cultivation Indicators in Asian Higher Education. South Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2014, 36, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, D.J.; O’Reilly, N.; Legg, D.; Levallet, N.; Fody, E. So You Want to Work in Sports? An Exploratory Study of Sport Business Employability. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 12, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrner, M.; Schüttoff, U. Analysing the Context-Specific Relevance of Competencies–Sport Management Alumni Perspectives. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacin, M.J.; VanSickle, J.L. Computer Program Usage in Sport Organizations and Computer Competencies Desired by Sport Organization Personnel. Int. J. Appl. Sport. Sci. 2014, 26, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinning, T. Preparing Sports Graduates for Employment: Satisfying Employers Expectations. High. Educ. Ski. Work. -Based Learn. 2017, 7, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos-Bastías, D.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Parra-Camacho, D.; Rendic-Vera, W.; Rementería-Vera, N.; Gajardo-Araya, G. Better Managers for More Sustainability Sports Organizations: Validation of Sports Managers Competency Scale (COSM) in Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.; Girginov, V.; Teoldo, I. What Do They Do? Competency and Managing in Brazilian Olympic Sport Federations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, W.J.; El-Khoury, M.; Brown, G.; Weese, W.Z. The Future Is Now: Preparing Sport Management Graduates in Times of Disruption and Change. Front. Sport. Act Living 2022, 4, 813504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.F. Enhancing University Student Employability through Practical Experiential Learning in the Sport Industry: An Industry-Academia Cooperation Case from Taiwan. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Ströbel, T. Global Sport Management Learning From Home: Expanding the International Sport Management Experience Through a Collaborative Class Project. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2022, 16, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraldo, C.M.; Yost, D. Service learning and travel abroad in the dominican republic: Developing competencies for international sport management. Int. J. Sport Manag. 2021, 22, 170–194. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, P.R.; Crabtree, R.M.; Kerr, A.K. The Australian Sport Management Job Market: An Advertisement Audit of Employer Need. Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megheirkouni, M. Leadership Competencies: Qualitative Insight into Non-Profit Sport Organisations. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2017, 13, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Fletcher, D.; Molyneux, L. Performance Leadership and Management in Elite Sport: Recommendations, Advice and Suggestions from National Performance Directors. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, I.; Shilbury, D.; Ferkins, L. Toward a Working Model of Leadership in Nonprofit Sport Governance. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfleegor, A.G.; Seifried, C.S. Where To Draw the Line? A Review of Ethical Decision-Making Models for Intercollegiate Sport Managers. J. Contemp. Athl. 2015, 9, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, G.M.; Magnusen, M.J.; Neubert, M.; Miller, G. Servant Leadership, Leader Effectiveness, and the Role of Political Skill: A Study of Interscholastic Sport Administrators and Coaches. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusen, M.; Kim, J.W. Thriving in the Political Sport Arena. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2016, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoppers, A.; Spaaij, R.; Claringbould, I. Discursive Resistance to Gender Diversity in Sport Governance: Sport as a Unique Field? Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2021, 13, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.B.; Pfister, G.U. Women in Sports Leadership: A Systematic Narrative Review. Int. Rev. Sociol Sport 2021, 56, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksteen, E.; Willemse, Y.; Malan, D.D.J.; Ellis, S. Competencies and Training Needs for School Sport Managers in the North- West Province of South Africa. J. Physic. Educ. Sport Manag. 2015, 6, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- ATILGAN, D.; KAPLAN, T. Investigation of the Relationship among Crisis Management, Decision-Making and Self-Confidence Based on Sport Managers in Turkey. Spor Bilim. Araştırmaları Derg. 2022, 7, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molan, C.; Matthews, J.; Arnold, R. Leadership off the Pitch: The Role of the Manager in Semi-Professional Football. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benar, N.; Ramezani Nejad, R.; Surani, M.; Gohar Rostami, H.; Yeganehfar, N. Designing a Managerial Skills Model for Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of Professional Sports Clubs in Isfahan Province. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 23, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjoribanks, T.; Farquharson, K. Contesting Competence: Chief Executive Officers and Leadership in Australian Football League Clubs. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, R.; Söderman, S. Strategic Sponsoring in Professional Sport: A Review and Conceptualization. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 271–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.M.; Eskerud, L.; Hanstad, D.V. Brand Creation in International Recurring Sports Events. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechner, D.; Filo, K.; Reid, S.; Cameron, R. A Systematic Literature Review of Charity Sport Event Sponsorship. Eur. Sport Manag. Quarterly. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauline, G. Engaging Students Beyond Just the Experience: Integrating Reflection Learning into Sport Event Management. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2016, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusen, M.; Perrewé, P.L. The Role of Social Effectiveness in Leadership: A Critical Review and Lessons for Sport Management. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2016, 10, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megheirkouni, M. Mixed Methods in Sport Leadership Research: A Review of Sport Management Practices. Choregia 2018, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.M.; Neubert, M.J.; Miller, G. Servant Leadership in Sport: A Review, Synthesis, and Applications for Sport Management Classrooms. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2018, 12, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, J.W.; Damon, Z.J.; Zhou, Y.; Burton, L.J. Forty Years of Leadership Research in Sport Management: A Review, Synthesis, and Conceptual Framework. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Groups | Survey | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Country | Italy | 6 | 25.0 | 16 | 44.4 |

| Latvia | 6 | 25.0 | 3 | 8.3 | |

| Lithuania | 6 | 25.0 | 7 | 19.4 | |

| Slovakia | 6 | 25.0 | 10 | 27.8 | |

| Age | ≤30 years (Younger) | 11 | 45.8 | 14 | 38.9 |

| >30 years (Older) | 13 | 54.2 | 22 | 61.1 | |

| Level | Entry | 8 | 33.3 | 13 | 36.1 |

| Middle | 10 | 41.7 | 14 | 38.9 | |

| Senior | 6 | 25.0 | 9 | 25.0 | |

| Assigned Clusters | Frequency of Occurrence (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | First | Second | SS | HS | C | BK | PT |

| Ability to deal with pressure/stress | SS | PT | 62.5 | 37.5 | |||

| Accountability/responsibility | PT | SS | 33.3 | 11.1 | 55.6 | ||

| Adaptability/flexibility skills | SS | PT | 36.4 | 18.2 | 45.5 | ||

| Analytical skills | C | HS | 44.4 | 55.6 | |||

| Appropriate working behavior/professionalism skills | SS | PT | 75.0 | 25.0 | |||

| Business and entrepreneurship | C | K | 10.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 10.0 | |

| Career awareness and planning skills | SS | C | 62.5 | 37.5 | |||

| Communication skills (written/oral) | HS | C | 66.7 | 33.3 | |||

| Conflict management skills | SS | C | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Constant availability | SS | PT | 60.0 | 40.0 | |||

| Controlling skills | C | · | 14.3 | 14.3 | 71.4 | ||

| Corporate social responsibility | K | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Creativity and innovation skills | PT | SS | 28.6 | 71.4 | |||

| Critical thinking | SS | · | 87.5 | 12.5 | |||

| Cross-cultural competence | C | K | 70.0 | 30.0 | |||

| Cultural and social awareness | SS | PT | 50.0 | 10.0 | 40.0 | ||

| Decision making skills | C | SS | 25.0 | 75.0 | |||

| Delegation skills | SS | PT | 50.0 | 10.0 | 40.0 | ||

| Education, qualification, academic achievement | K | HS | 42.9 | 57.1 | |||

| Effective interpersonal communication skills (internal/external) | SS | PT | 70.0 | 30.0 | |||

| Emotional and interpersonal intelligence skills | SS | PT | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Ethical commitment and behavior/integrity | SS | PT | 54.5 | 45.5 | |||

| Evaluation skills | C | K | 11.1 | 44.4 | 44.4 | ||

| Event management | C | K | 55.6 | 44.4 | |||

| Facility/operations management | C | K | 77.8 | 22.2 | |||

| Finance and administration management | K | HS | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Foreign languages | K | HS | 42.9 | 14.3 | 42.9 | ||

| Fundraising and grant writing | C | K | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| General work-related experience | C | SS | 42.9 | 14.3 | 42.9 | ||

| Goal orientation-setting skills | C | SS | 37.5 | 62.5 | |||

| Human resources management | K | HS | 30.0 | 10.0 | 60.0 | ||

| Information management | C | HS | 44.4 | 55.6 | |||

| Initiative/proactivity | PT | SS | 28.6 | 71.4 | |||

| Knowledge transfer to practice skills | C | · | 16.7 | 66.7 | 16.7 | ||

| Leadership skills | SS | PT | 54.5 | 45.5 | |||

| Learning (skills and will) | PT | · | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 62.5 | |

| Legal knowledge and sports law | K | HS | 33.3 | 66.7 | |||

| Marketing knowledge | K | C | 12.5 | 25.0 | 62.5 | ||

| Maturity | PT | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Meetings management | C | SS | 25.0 | 12.5 | 50.0 | 12.5 | |

| Motivation/enthusiasm/passion | PT | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Negotiation skills | SS | PT | 50.0 | 10.0 | 40.0 | ||

| Networking | SS | PT | 55.6 | 44.4 | |||

| Personal management | SS | PT | 44.4 | 11.1 | 44.4 | ||

| Planning/organization/coordination skills | C | HS | 28.6 | 71.4 | |||

| Political skills | SS | C | 55.6 | 33.3 | 11.1 | ||

| Practical intelligence skills | C | SS | 25.0 | 62.5 | 12.5 | ||

| Problem solving skills | C | SS | 25.0 | 62.5 | 12.5 | ||

| Project management | C | HS | 37.5 | 50.0 | 12.5 | ||

| Relatability | SS | PT | 50.0 | 12.5 | 37.5 | ||

| Research skills | HS | K | 42.9 | 14.3 | 42.9 | ||

| Resilience/perseverance | PT | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Respect of hierarchies, role boundaries, and responsibilities | SS | PT | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Risk management | C | K | 11.1 | 44.4 | 44.4 | ||

| Safety/security/health management | C | HS | 33.3 | 55.6 | 11.1 | ||

| Self-confidence | PT | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Social judgment skills | PT | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Social self-efficacy | PT | · | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| Social skills/people skills | SS | PT | 50.0 | 50.0 | |||

| Sponsorship management | C | K | 75.0 | 25.0 | |||

| Sports history and philosophy | K | · | 100.0 | ||||

| Sports participation/involvement/knowledge | K | · | 16.7 | 83.3 | |||

| Stakeholder management | C | SS | 28.6 | 57.1 | 14.3 | ||

| Strategic management and ability to manage change | K | C | 25.0 | 75.0 | |||

| Tasks and resources management | C | HS | 25.0 | 75.0 | |||

| Teamwork | SS | PT | 55.6 | 44.4 | |||

| Technological/digital/social media skills | HS | K | 71.4 | 28.6 | |||

| Time management skills | SS | PT | 71.4 | 28.6 | |||

| Transferable skills | C | · | 85.7 | 14.3 | |||

| Volunteer management | C | K | 57.1 | 42.9 | |||

| Working autonomy skills | SS | PT | 50.0 | 10.0 | 40.0 | ||

| Assigned Clusters | Item | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BK | History of sports and sports philosophy | 6.0 | ± | 0.0 |

| PT & SS | Ability to deal with pressure/stress | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 |

| PT & SS | Teamwork | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 |

| C & HS | Information management | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 |

| C | Knowledge transfer to practice | 5.7 | ± | 0.8 |

| BK & HS | Legal knowledge and sports law | 5.7 | ± | 0.8 |

| C & HS | Tasks and resources management | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 |

| C | Transferable skills | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 |

| PT & SS | Adaptability/flexibility skills | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 |

| PT & SS | Effective interpersonal communication skills | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 |

| BK & HS | Education, qualification, academic achievement | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| BK & HS | Finance and administration management | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| BK & HS | Research skills | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| C & HS | Communication skills (written/oral) | 5.5 | ± | 0.5 |

| PT & SS | Accountability/responsibility | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT & SS | Initiative/proactivity | 5.5 | ± | 0.5 |

| PT | Motivation/enthusiasm/passion | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT & SS | Respect of hierarchies, role boundaries, and responsibilities | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT & SS | Delegation skills | 5.5 | ± | 0.5 |

| PT | Resilience/perseverance | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT | Self-confidence | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| C | Controlling skills | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| C & SS | Decision-making skills | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| BK & HS | Foreign languages | 5.3 | ± | 1.2 |

| C & HS | Safety/security/health management | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| BK & C | Sponsorship management | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT & SS | Appropriate working behavior/professionalism | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT | Social self-efficacy | 5.3 | ± | 0.5 |

| PT & SS | Networking | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| C & HS | Analytical skills | 5.2 | ± | 1.0 |

| BK & C | Marketing | 5.2 | ± | 1.2 |

| BK & C | Risk management | 5.2 | ± | 1.0 |

| PT & SS | Creativity and innovation | 5.2 | ± | 1.0 |

| PT & SS | Emotional and interpersonal intelligence | 5.2 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT & SS | Leadership skills | 5.2 | ± | 1.2 |

| PT & SS | Negotiation skills | 5.2 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT | Maturity | 5.2 | ± | 1.0 |

| PT & SS | Relatability | 5.2 | ± | 1.0 |

| BK & C | Facility/operations management | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 |

| BK & C | Fundraising and grant writing | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 |

| C & SS | Goal orientation-setting | 5.0 | ± | 0.6 |

| C & SS | Meetings management | 5.0 | ± | 1.3 |

| C & HS | Project management | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 |

| C & SS | Problem solving | 5.0 | ± | 1.1 |

| BK & C | Strategic management and ability to manage change | 5.0 | ± | 1.3 |

| BK & HS | Technological/digital/social media skills | 5.0 | ± | 1.5 |

| C & SS | Career awareness and planning | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 |

| SS | Critical thinking | 5.0 | ± | 1.1 |

| PT & SS | Ethical behavior/integrity | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 |

| PT & SS | Time management | 5.0 | ± | 0.6 |

| PT & SS | Working autonomy | 5.0 | ± | 0.6 |

| BK & C | Business and entrepreneurship | 4.8 | ± | 1.5 |

| BK | Specific knowledge of the sports context | 4.8 | ± | 1.6 |

| PT | Learning (skills and will) | 4.8 | ± | 1.3 |

| PT | Social judgment skills | 4.8 | ± | 0.8 |

| PT & SS | Personal management | 4.7 | ± | 1.0 |

| C & SS | Conflict management skills | 4.5 | ± | 1.6 |

| BK & C | Evaluation skills | 4.5 | ± | 1.0 |

| C & SS | General work-related experience | 4.5 | ± | 1.0 |

| C & HS | Planning/organization/coordination skills | 4.5 | ± | 0.8 |

| C & SS | Political skills | 4.3 | ± | 1.2 |

| BK & C | Event management | 4.3 | ± | 1.2 |

| BK & C | Volunteer management | 4.3 | ± | 1.6 |

| PT & SS | Constant availability | 4.3 | ± | 1.0 |

| BK | Corporate Social Responsibility | 4.2 | ± | 1.2 |

| C & SS | Practical intelligence | 4.0 | ± | 1.4 |

| C & SS | Stakeholder management | 4.0 | ± | 0.6 |

| C & SS | Cross-cultural competence | 3.8 | ± | 1.5 |

| BK & C | Human resources management | 3.7 | ± | 1.6 |

| Recorded Items for Level | Major Clusters | Items (n) | Items with ≥ 3 Citations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BK | 4 | Learning (skills and will) | Initiative, proactivity | Personal management | |

| C | 7 | Motivation, enthusiasm, passion | Appropriate working behavior, professionalism skills | Respect for hierarchies, role boundaries, and responsibilities | |

| Entry n = 37 | HS | 5 | Education, qualification, academic achievement | Communication skills (written/oral) | Social skills/people skills |

| PT | 3 | Adaptability, flexibility skills | Accountability, responsibility | Teamwork | |

| SS | 18 | Technological, digital, social media skills | Creativity and innovation skills | Working autonomy skills | |

| BK | 8 | Analytical skills | Human resources | ||

| C | 18 | Project management | Controlling skills | ||

| Middle n = 48 | HS | 4 | Problem solving skills | Time management skills | |

| PT | 2 | Event management | |||

| SS | 16 | Finance and administration | |||

| BK | 8 | Strategic management and change management | Planning, organization, coordination skills | Motivation, enthusiasm, passion | |

| C | 13 | Political skills | Ability to deal with pressure/stress | Conflict management skills | |

| Senior n = 38 | HS | 2 | Leadership skills | Accountability, responsibility | Critical thinking |

| PT | 1 | Finance and administration | Decision-making skills | Networking | |

| SS | 14 | Human resources | Risk management | Teamwork | |

| Managerial Levels | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Cluster—Item | Entry (pt.) | Middle (pt.) | Senior (pt.) | ||||||

| BK—Human resources | 3.4 | ± | 1.4 | 4.6 | ± | 1.3 | 4.8 | ± | 1.5 |

| BK—Marketing | 4.6 | ± | 1.0 | 4.8 | ± | 1.2 | 5.6 | ± | 0.5 |

| BK—Sports knowledge | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 | 5.1 | ± | 1.0 | 5.9 | ± | 0.3 |

| C—Evaluation skills | 4.2 | ± | 1.0 | 5.1 | ± | 0.8 | 5.5 | ± | 1.4 |

| C—Practical intelligence skills | 4.5 | ± | 1.3 | 5.2 | ± | 0.7 | 5.6 | ± | 0.9 |

| HS—Communication skills (written/oral) | 4.6 | ± | 0.8 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 | 5.7 | ± | 0.6 |

| HS—Foreign languages | 5.3 | ± | 1.0 | 5.7 | ± | 0.6 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 |

| PT—Motivation/enthusiasm/passion | 5.7 | ± | 0.9 | 5.2 | ± | 0.8 | 5.6 | ± | 0.9 |

| SS—Ability to deal with pressure/stress | 4.5 | ± | 0.9 | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 |

| SS—Accountability/responsibility | 4.8 | ± | 1.2 | 5.6 | ± | 0.7 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 |

| SS—Adaptability/flexibility skills | 4.8 | ± | 0.8 | 5.7 | ± | 0.6 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 |

| SS—Appropriate working behavior/professionalism skills | 5.2 | ± | 0.9 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 | 5.9 | ± | 0.3 |

| SS—Creativity and innovation skills | 4.5 | ± | 1.4 | 5.4 | ± | 0.7 | 5.0 | ± | 1.0 |

| SS—Critical thinking | 4.2 | ± | 0.9 | 5.3 | ± | 0.6 | 5.8 | ± | 0.8 |

| SS—Emotional and interpersonal intelligence skills | 4.4 | ± | 0.9 | 5.4 | ± | 0.8 | 5.1 | ± | 1.0 |

| SS—Ethical behavior/integrity | 4.6 | ± | 0.9 | 5.5 | ± | 0.8 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 |

| SS—Networking | 4.2 | ± | 1.1 | 5.6 | ± | 0.8 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 |

| SS—Social skills/people skills | 4.9 | ± | 1.0 | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 | 5.4 | ± | 0.5 |

| SS—Teamwork | 5.5 | ± | 1.0 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 |

| BK—Education, qualification, academic achievement | 5.0 | ± | 1.3 | 5.5 | ± | 0.9 | |||

| C—General work-related experience | 4.6 | ± | 1.4 | 5.2 | ± | 0.9 | |||

| C—Knowledge transfer to practice skills | 4.4 | ± | 1.3 | 5.2 | ± | 1.1 | |||

| C—Volunteer management | 3.5 | ± | 1.3 | 5.2 | ± | 0.7 | |||

| HS—Information management | 5.0 | ± | 1.3 | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 | |||

| HS—Research skills | 4.7 | ± | 1.5 | 5.3 | ± | 0.6 | |||

| PT—Initiative/proactivity | 5.3 | ± | 0.9 | 5.2 | ± | 0.6 | |||

| SS—Effective interpersonal communication skills | 4.8 | ± | 1.1 | 5.7 | ± | 0.6 | |||

| SS—Time management skills | 5.1 | ± | 1.0 | 5.5 | ± | 0.7 | |||

| SS—Working autonomy skills | 4.8 | ± | 1.0 | 5.2 | ± | 0.8 | |||

| C—Goal orientation-setting skills | 4.5 | ± | 1.3 | 5.7 | ± | 0.9 | |||

| BK—Business and entrepreneurship | 4.8 | ± | 1.1 | 5.6 | ± | 0.5 | |||

| BK—Event management | 4.9 | ± | 1.3 | 5.6 | ± | 0.5 | |||

| BK—Finance and administration | 4.9 | ± | 1.1 | 5.7 | ± | 0.6 | |||

| BK—Legal knowledge and sports law | 4.8 | ± | 1.1 | 5.7 | ± | 0.5 | |||

| C—Analytical skills | 4.9 | ± | 1.2 | 5.6 | ± | 1.4 | |||

| C—Controlling skills | 5.0 | ± | 0.9 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 | |||

| C—Decision making skills | 5.2 | ± | 0.8 | 5.9 | ± | 0.3 | |||

| C—Planning/organization/coordination skills | 5.2 | ± | 0.6 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 | |||

| C—Problem solving skills | 5.1 | ± | 1.0 | 5.8 | ± | 0.6 | |||

| C—Project management | 5.2 | ± | 1.1 | 5.3 | ± | 0.9 | |||

| C—Risk management | 5.0 | ± | 0.8 | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 | |||

| C—Stakeholder management | 4.8 | ± | 0.8 | 5.7 | ± | 0.9 | |||

| C—Tasks and resources management | 5.2 | ± | 0.9 | 5.5 | ± | 0.7 | |||

| C—Transferable skills | 4.8 | ± | 0.9 | 5.4 | ± | 0.9 | |||

| SS—Conflict management skills | 5.4 | ± | 0.5 | 5.8 | ± | 0.8 | |||

| SS—Leadership skills | 5.8 | ± | 0.4 | 5.8 | ± | 0.8 | |||

| Item | Level | Score (pt.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C—Cross-cultural competence | Entry | 3.8 | ± | 0.7 |

| HS—Technological/digital/social media skills | Entry | 4.7 | ± | 1.0 |

| PT—Learning (skills and will) | Entry | 4.5 | ± | 1.0 |

| SS—Career awareness and planning skills | Entry | 4.3 | ± | 0.8 |

| SS—Meetings management | Entry | 4.5 | ± | 1.3 |

| SS—Personal management | Entry | 4.2 | ± | 1.2 |

| SS—Respect of hierarchies, roles, and responsibilities | Entry | 5.2 | ± | 1.0 |

| C—Facility/operations management | Middle | 4.9 | ± | 1.0 |

| C—Fundraising and grant writing | Middle | 4.8 | ± | 1.1 |

| C—Sponsorship management | Middle | 4.7 | ± | 1.0 |

| BK—Strategic management and ability to manage change | Senior | 5.9 | ± | 0.3 |

| SS—Political skills | Senior | 5.5 | ± | 0.9 |

| Significant Correlations (p ≤ 0.01) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label | Items | R-P | R-NT | P-NT |

| Controlling skills | Item 6 | 0.836 * | ||

| Cross-cultural competence | Item 7 | 0.714 * | ||

| Foreign languages | Item 14 | 0.774 * | ||

| Education, qualification, academic achievement | Item 46 | 0.772 * | NA | NA |

| Learning (skills and will) | Item 52 | 0.703 * | NA | NA |

| Motivation/enthusiasm/passion | Item 53 | 0.750 * | NA | NA |

| Personal management | Item 54 | 0.794 * | NA | NA |

| Sports knowledge | Item 57 | 0.744 * | NA | NA |

| Teamwork | Item 58 | 0.804 * | NA | NA |

| Age | Level | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Overall | Younger | Older | Entry | Middle | Senior | |||||||||||||

| BK | R | 4.5 | ± | 0.8 | 4.7 | ± | 0.7 | 4.4 | ± | 0.9 | 4.6 | ± | 0.6 | 4.6 | ± | 1.0 | 4.2 | ± | 0.9 |

| P | 3.7 | ± | 0.9 | 4.0 | ± | 0.9 | 3.6 | ± | 0.9 | 3.9 | ± | 1.0 | 3.6 | ± | 0.8 | 3.8 | ± | 0.8 | |

| NT | 4.8 | ± | 0.9 | 4.8 | ± | 0.9 | 4.7 | ± | 1.0 | 4.9 | ± | 1.1 | 4.6 | ± | 0.9 | 4.8 | ± | 0.7 | |

| C | R | 4.7 | ± | 0.8 | 4.7 | ± | 0.8 | 4.6 | ± | 0.8 | 4.8 | ± | 0.8 | 4.7 | ± | 0.7 | 4.5 | ± | 0.9 |

| P | 4.2 | ± | 0.7 | 4.3 | ± | 0.8 | 4.2 | ± | 0.7 | 4.4 | ± | 0.9 | 4.0 | ± | 0.6 | 4.4 | ± | 0.6 | |

| NT | 4.6 | ± | 0.9 | 4.8 | ± | 0.9 | 4.6 | ± | 0.8 | 4.9 | ± | 1.0 | 4.5 | ± | 0.8 | 4.6 | ± | 0.7 | |

| HS | R | 4.5 | ± | 0.9 | 4.5 | ± | 0.9 | 4.5 | ± | 1.0 | 4.3 | ± | 0.7 | 4.8 | ± | 1.0 | 4.5 | ± | 1.1 |

| P | 3.9 | ± | 0.9 | 3.9 | ± | 0.8 | 4.0 | ± | 0.9 | 3.8 | ± | 1.0 | 3.9 | ± | 0.7 | 4.3 | ± | 1.0 | |

| NT | 4.5 | ± | 1.0 | 4.6 | ± | 1.1 | 4.5 | ± | 0.9 | 4.7 | ± | 1.1 | 4.3 | ± | 1.0 | 4.7 | ± | 0.7 | |

| IND | R | 4.4 | ± | 0.8 | 4.2 | ± | 1.0 | 4.6 | ± | 0.7 | 4.3 | ± | 1.1 | 4.6 | ± | 0.6 | 4.4 | ± | 0.7 |

| P | 4.5 | ± | 0.8 | 4.3 | ± | 1.0 | 4.7 | ± | 0.7 | 4.4 | ± | 1.1 | 4.6 | ± | 0.6 | 4.6 | ± | 0.7 | |

| NT | 4.7 | ± | 0.9 | 4.7 | ± | 0.9 | 4.7 | ± | 0.9 | 4.9 | ± | 0.9 | 4.6 | ± | 0.8 | 4.6 | ± | 0.9 | |

| Variables | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | IND_ R | IND_ P | IND_ NT | C_ R | C_ P | C_ NT | HS_ R | HS_ P | HS_ NT | BK_ R | BK_ P | BK_ NT | |

| IND_R | CC | 0.873 ** | |||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| IND_NT | CC | 0.844 ** | 0.755 ** | 0.816 ** | |||||||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| C_R | CC | 0.733 ** | 0.830 ** | ||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| C_P | CC | 0.712 ** | |||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| C_NT | CC | 0.865 ** | 0.917 ** | ||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| HS_R | CC | 0.774 ** | |||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| HS_P | CC | 0.775 ** | |||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| HS_NT | CC | 0.815 ** | |||||||||||

| p | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Sports Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: Focus Groups and Women Sports Managers’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310335

Guidotti F, Demarie S, Ciaccioni S, Capranica L. Sports Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: Focus Groups and Women Sports Managers’ Perceptions. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310335

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuidotti, Flavia, Sabrina Demarie, Simone Ciaccioni, and Laura Capranica. 2023. "Sports Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: Focus Groups and Women Sports Managers’ Perceptions" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310335

APA StyleGuidotti, F., Demarie, S., Ciaccioni, S., & Capranica, L. (2023). Sports Management Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills: Focus Groups and Women Sports Managers’ Perceptions. Sustainability, 15(13), 10335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310335