Abstract

The adoption of the circular economy (CE) can help to solve the dilemmas of food, economic and social crises, environmental pollution, and continuous decreases in non-renewable resources, caused by the continuous increase in the size of the global population. Identifying drivers of and barriers to the CE is important for the implementation of the CE. In this context, this study aims to identify and categorize the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE through a systematic literature review. In doing this, ten categories of drivers and barriers were identified: environmental, supply chain, economic, information, legal, market, organizational, public, social, and technological. The results of this study may contribute to the development of circular processes, the promotion of sustainability, and may encourage the implementation of the CE in many areas. The CE’s implementation can be a way to achieve some of the Sustainable Development Goals from the 2030 Agenda.

1. Introduction

We live in an era of food, economic, and social crises, environmental pollution, growing awareness of social responsibility, sustainability, and concern for the environment, and heightened growth in some economies, coupled with urbanization [1,2]. The modern economy threatens environmental protection, and this fact places pressure on environmental stakeholders, especially firms and policymakers [2]. Arising from the perception that current consumption patterns are at the root of the environmental crisis, criticism of consumerism came to be seen as a contribution to the development of sustainable societies [3]. In this sense, the adoption of the circular economy (CE) is seen as one of the ways that we might solve this dilemma. The CE paradigm aims to attain sustainability by preventing environmental degradation and ensuring the social and economic wellbeing of present and future generations [4]. CE has become a popular strategy for improving sustainability, and is a theme that has been extensively researched over the past five years [5]. Arthur et al. (2023) [2] assumed that some CE variables have a significant impact on the environment; variables such as the level of materials considered as input factors for economic production, the amount of waste generated because of the extraction and usage of these materials, and the rate of recycling of the generated waste.

From a different perspective, while the terms circular economy and sustainability are increasingly gaining traction within academia, industry, and for policymakers, and are often being used in similar contexts, the similarities and differences between these concepts have not been made explicit in the literature, and remain ambiguous [6]. However, Velenturf and Purnell (2021) [7] suggest every actor should do their very best to develop a more sustainable CE, which requires research and constant learning to ensure progress towards sustainability, even with imperfections.

The adoption of the CE fosters a reduction in the consumption of raw materials, improves brand image, encourages the emergence of new demands for services and new potential markets, reduces the costs and risks of emissions and waste, and increases the potential to attract new investors [8]. Therefore, the CE approach has attracted the attention of many firms, enabling them to make the production process more efficient, especially when material and energy inputs become more expensive [9]. Considering the importance of the topic, a growing number of authors have explored the theme of the CE, specifically its drivers and barriers. However, some studies have focused only on issues that facilitate the implementation of the CE (drivers) [10,11,12], while other studies have focused only on factors that hinder the implementation of the CE (barriers) [13,14,15,16,17]. Some studies deal with both drivers and barriers, but in specific contexts, e.g., the supply chain [18,19], the textile and apparel industry [20], small and medium enterprises [21], and the building and infrastructure sector [22], or in specific countries, e.g., Brazil [23], China [24], Taiwan [25] and Finland [26]. Additionally, there are some studies in the literature that have only categorized drivers of the CE in the leather industry [27] and in the Italian economy [10]; and barriers to the CE applied to the Danish economy [15], to the construction sector [28], and to five European regions [29], as well as both (drivers and barriers) applied together to the built environment sector [22] and to the manufacturing sector in the UK [30]. Moreover, Mishra et al. (2022) [31] developed, measured, and validated an instrument for barriers to the adoption of the CE practices in micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), determining seven dimensions; however, the drivers for the adoption of the CE were not considered in their study.

An in-depth and complete analysis joining the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE is necessary to enable a general application. Elia et al. (2020) [32] analyzed the relationship between the level of supply chain integration and the adopted CE strategies from the industrial field, rather than specifically analyzing the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. Thus, notwithstanding the studies that have already been completed, in the literature, there is a lack of investigation into these drivers and barriers in a more detailed way that could be applied to multiple sectors [18,27], different markets [33], distinct economies [23], and different geographic contexts [19]. Additionally, Jia et al. (2020) [20] demand more databases to find relevant articles. In this sense, searching for a theoretical proposition that can help to attend to such demands, this study aims to identify and categorize the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE for a general application.

The study contributes in different ways to research and practice in the CE field. It extends the body of knowledge on CE by assessing a significant number of papers that contain the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE, equipping researchers and practitioners with prior information about the realities that will be faced. It also helps in planning for the transition from a linear economy to CE, making companies more efficient with their resources and advancing toward sustainable economies [14]. The results of D’Adamo and Gastaldi (2022) [34] in their study regarding the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) showed that many sustainability opportunities have not yet been well explored. In this sense, the adoption of the CE can be considered a way to achieve some of the SDGs, e.g., companies producing with more responsibility, encouraging them, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices (goal 12) and reducing the environmental impact of cities through waste management (goal 11). Additionally, Ali et al. (2023) [35] mention circular economy-centric education being the solution to the social, economic, and environmental problems stemming from climate change. Moreover, green technologies, through the optimization of the use of resources, the reduction of waste, and the reduction of demand for new resources, may promote the development of green products and services, thereby helping to reduce the environmental impact of consumption [35]. The study presents an extended literature review, enabling a broader view and a categorization of the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. These contributions are important to help companies develop the CE and help the government obtain knowledge to work on public policies fostering the CE. It is important to have a clear understanding of the context of the CE in order to provide a common basis of assumptions and targets on which policymaking can be developed [36]. Additionally, it would facilitate practitioners to understand the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE to handle them effectively.

To summarize, the present study addresses the following research question: What are the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE, and how can we categorize them according to the literature?

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 and Section 3 present the theoretical basis and material and methods of the study, respectively. The fourth section presents the results and discussion of the paper. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by presenting the implications and limitations of the study, and suggestions for future studies.

2. Theoretical Basis

2.1. Circular Economy

The concept of the CE, which was created primarily by practitioners, the business community, and policymakers, is currently promoted by the European Union, several national governments, and various business organizations around the world [8]. CE is becoming part of popular discourse, especially in the government and corporate sector [37].

The CE focuses on the maintenance, reuse/redistribution/remanufacturing/recycling, circularity and optimization of resources, the use of clean energy, and processing efficiency, with zero waste as a basic premise [38]. According to Zhang et al. (2022) [4] (p. 656), the CE is perceived as a substitute for the take–make–waste linear economy.

The concept involves careful management of two types of material flows, as described by McDonough and Braungart (2010) [39]: biological nutrients, designed to re-enter the biosphere safely and build natural capital, and technical nutrients, designed to circulate in high quality without entering the biosphere. According to Sehnem and Pereira (2019) [38], the CE emphasizes the biological cycle and technical cycle of materials.

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2019) [40], the CE is based on three principles: (1) designing waste and pollution, (2) keeping products and materials in use, and (3) regenerating natural systems. It makes sense to extract resources from nature to transform them into a product or service that can be used not just once, but many times, thus reducing the need for virgin input extraction and waste production [8]. Designing waste, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems creates vital opportunities for economic growth, thereby creating jobs and benefiting society [41]. Substantially reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse, and achieving sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources are some goals of the 12th SDG, proposed in the 2030 Agenda (2015) [42].

While the CE is increasingly attracting attention in academia, industry, and with policymakers [6], Friant et al. (2020) [37] argue that the definition, objectives, and forms of implementation of the CE are still unclear, inconsistent, and contested. This is the case because different actors and sectors are articulating circular discourses which align with their own interests and which do not often sufficiently examine the ecological, social, and political implications of circularity [37]. In line with these authors, Corvellec et al. (2022) [43] addressed critiques of the CE in their study, considering that the CE has diffused limits, unclear theoretical grounds, and that its implementation faces structural obstacles. According to Velenturf and Purnell (2021) [7], every actor should do their very best to develop a more sustainable CE. Sustainable development is fraught with imperfection, and so is the circular economy, both requiring research and constant learning to ensure progress in pursuit of sustainability [7].

Joining the CE allows for a reduction in the consumption of raw materials [8] and gains in resource efficiency [19,44], thus promoting waste reduction [30], in addition to reducing a company’s environmental impact [10].

The cost reductions arising from the implementation of the CE are one of the most frequently considered aspects in the literature [26,44]. The CE encourages the emergence of new demands for services and expansion into new markets, thus increasing a company’s potential to attract new investors [8], and generating competitive advantages for circular companies [10,20].

In addition, the adoption of the CE makes it possible to improve the reputation and recognition of the brand [8], the relationship with customers [44], and to increase consumer satisfaction [10]. The adoption of the CE is also seen as a potential source of new jobs [33].

2.2. Drivers and Barriers to the Circular Economy

As the concept of the CE becomes more prevalent among the topics covered in the literature, more studies are focusing on the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. Many authors have worked with drivers of the adoption of the CE in their studies to encourage, motivate, and facilitate companies to adopt the CE [18,22,27,33], thus helping in the transition from a linear economy to the CE; it is thought that the CE is much more efficient in resources, and will generate greater competitiveness for the company and advancement towards a more sustainable economy [14].

Some of the main drivers addressed by the literature were concern for environmental impact and the environment [27]; increased transparency and engagement in the supply chain [26]; reduced costs [45,46]; the existence of laws and regulations regarding the CE [47]; awareness of environmental issues among consumers [18]; investment in science and technology [19,48]; and government support [21,49]. In this sense, Arthur et al. (2023) [2] concluded in their study that a blend of government policies is the most effective means of achieving a CE.

Drivers regarding companies, such as increasing the network and partnerships [50] and gains in market share and competitiveness [33], were also heavily addressed in the literature.

On the other hand, many studies have also pointed out the barriers to the adoption of the CE, hindering or inhibiting its implementation [30,33,51]. There is a lack of funding [19], financial resources [29], economies of scale [52], appropriate technology for the CE [47], information [36], and laws and rules supporting the CE [18]. Furthermore, the initial investment cost for companies is high [52].

Within the market, demand for circular products and processes is still restricted [29], and there is a lack of environmental awareness among consumers [53]. In companies, there is a lack of commitment at the management level [54], and a shortage of qualified personnel to work with CE [55]. There is also a lack of encouragement and support from the government [56].

The literature has categorized the presentation of drivers and barriers in different ways. Table 1 presents the categorization of only drivers, only barriers, and both drivers and barriers, from the literature.

Table 1.

Categorization of drivers and barriers from the literature.

3. Materials and Methods

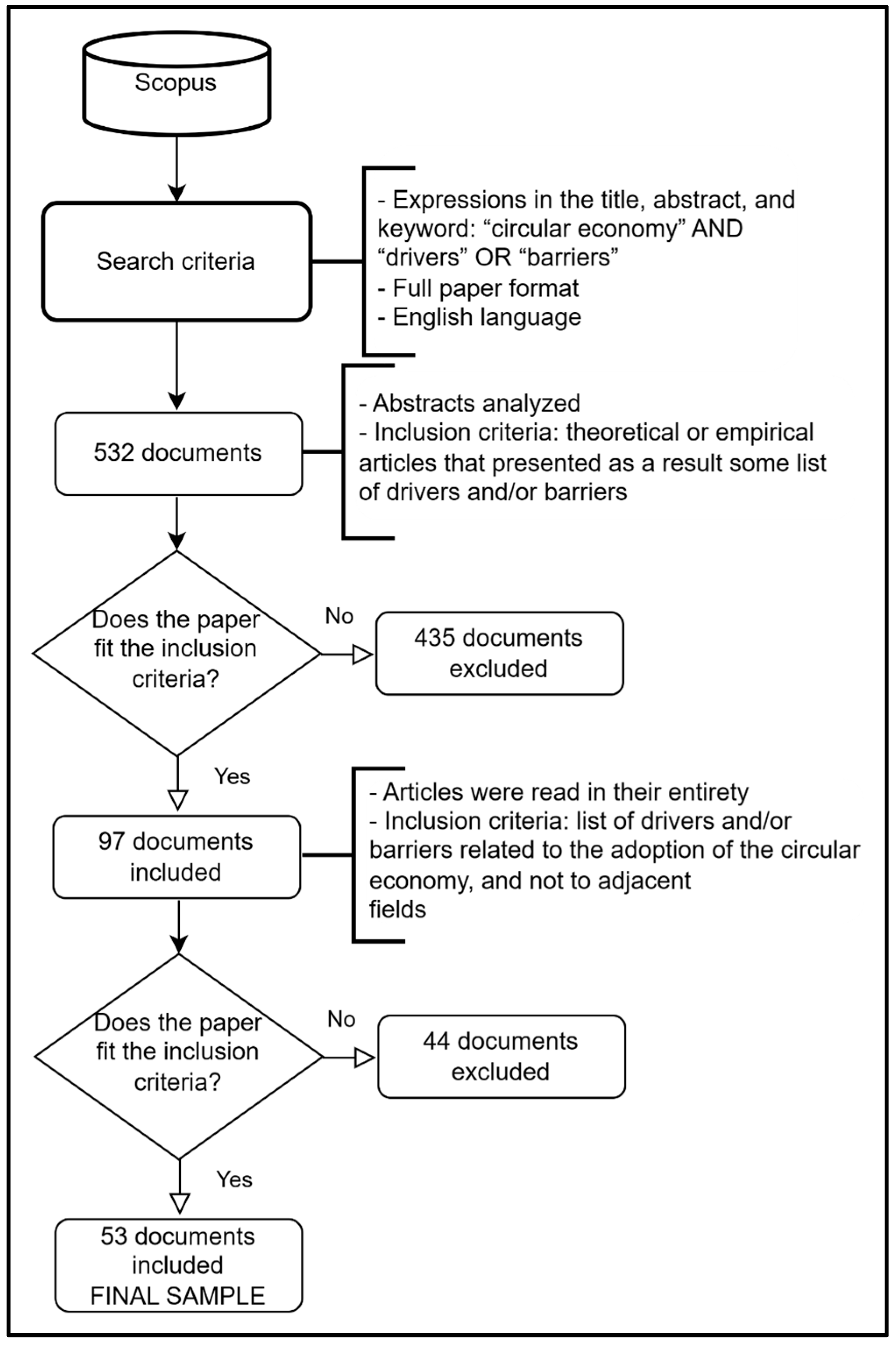

In order to identify and categorize drivers and barriers to the adoption of the CE, a systematic literature review was used as a method, as suggested by Snyder (2019) [59]. The method used consists of a content analysis of selected studies based on specific criteria defined by the authors. This study followed four stages, as suggested by Wolfswinkel et al. (2013) [60] and Flores and Jansson (2022) [61].

3.1. Stage 1—Selection of Database

First, the database to be used was identified. Following Paul and Criado (2020) [62], we decided to use Scopus, as it captures more articles than Web of Science and includes the main journals, thus providing a more comprehensive and relevant set of articles that could potentially be relevant, even considering that this decision may have resulted in the unintentional exclusion of other pertinent papers listed in other databases. Scopus is a consolidated database that is widely used in systematic review studies [18,19,63].

3.2. Stage 2—Selection of Keywords and Search for Studies According to Clear Criteria

After selecting the database, we needed to determine the keywords for searching relevant papers. The expressions used when searching the title, abstract, and keyword fields were “circular economy” AND “drivers” OR “barriers”. We have not included synonyms, as the selected keywords are well-established terms used in academia. We considered papers and articles published in English, limiting the results to academic/scientific journals and conference proceedings. Only full papers were included, and book chapters, reviews, and books were excluded. This produced a list of 532 papers for further analysis.

3.3. Stage 3—Selection of Articles

To select the articles to be reviewed and included in our paper, we applied the following criteria: (1) the abstracts of the 532 selected articles were analyzed. As inclusion criteria, they had to be theoretical or empirical articles that presented, as a result, a list of drivers and/or barriers. Based on this criterion, 435 articles were excluded, and 97 articles were selected for inclusion. (2) These 97 articles were then read in their entirety to verify that the lists of drivers and/or barriers were related to the adoption of the circular economy, and not to adjacent fields that were not of interest to our study, such as recycling, sustainability, and green marketing. Thus, 44 articles were excluded, and 53 articles were included.

3.4. Stage 4—Analysis through Data Coding and Structuring of Findings

A spreadsheet was created for the analysis of the 53 selected articles. The information from these articles was released in the form of an Excel spreadsheet. The articles were tabulated under title, year and place of publication, area, sector, or geographic context in which the study was carried out, objectives, methodological approach, and the main conclusions, as well as the list of drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE found in the articles. Data were analyzed using the content analysis technique [64]. To ensure the quality of the interpretation, the drivers and barriers emanating from the literature were systematically organized according to Wolfswinkel et al. (2013) [60], Xiao and Watson (2019) [65], and Flores and Jansson (2022) [61]. In cases in which there were doubts regarding the organization of the drivers and barriers among the categories defined by the authors of this study, a discussion took place between the authors until a consensus was reached.

The flowchart in Figure 1 presents the research process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the research design.

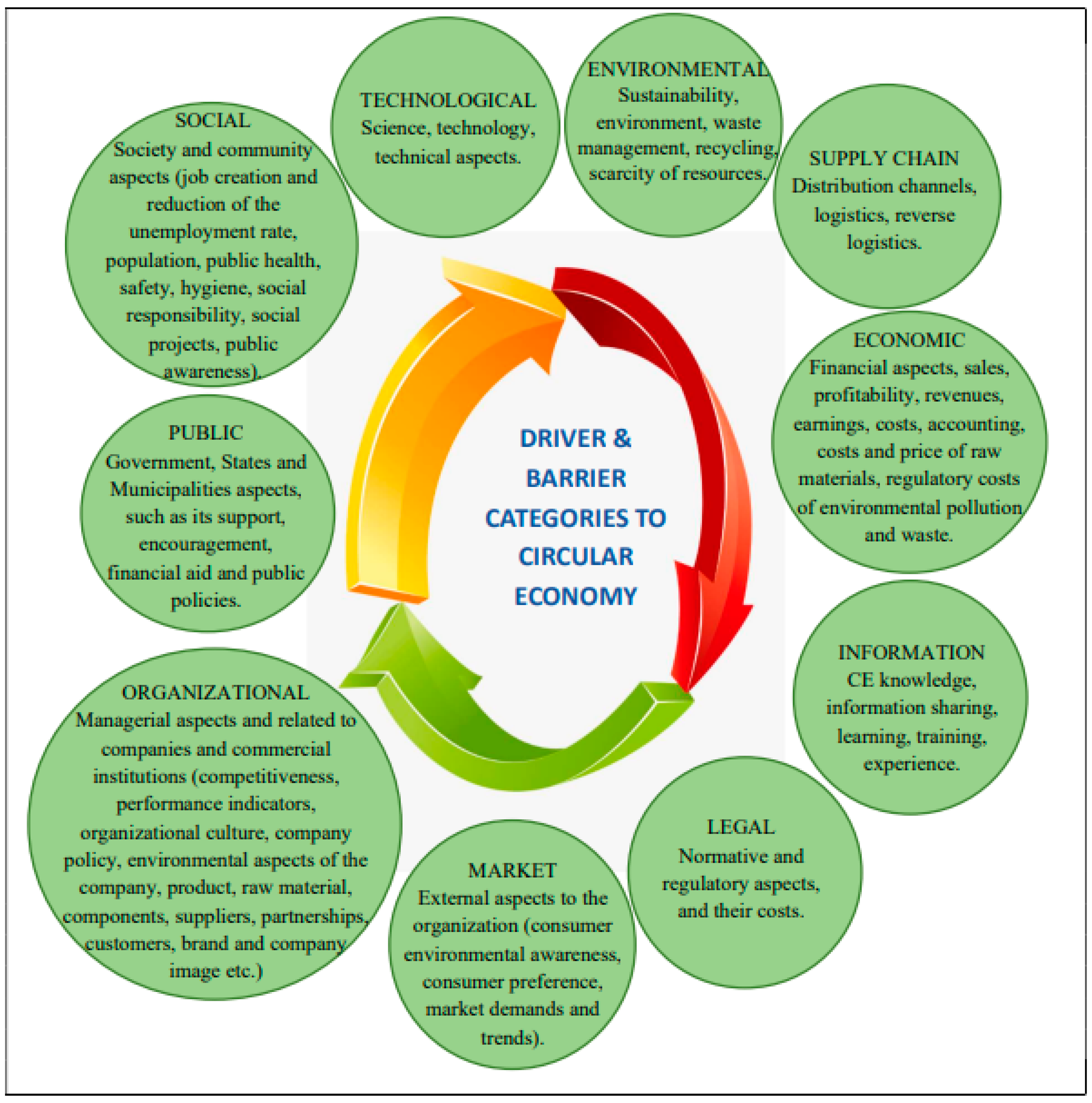

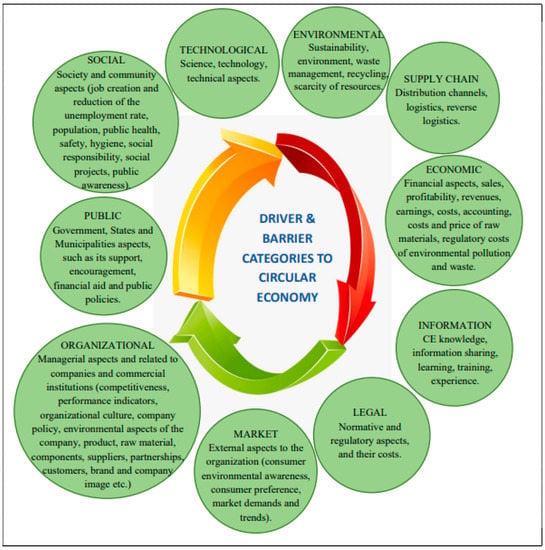

It was observed that some studies categorized the presentation of drivers and barriers in their research (Table 1). So, based initially on the literature review categorization of drivers and barriers, presented in Table 1, the list of drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE was grouped, and ten categories were created for the purpose of the final presentation of the study results.

The first category identified for the present study was the environmental category. Nohra et al. (2020) [29] and Kumar et al. (2019) [30] used the environmental category to present barriers to the CE, and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used the environmental category to present drivers of and barriers to the CE. In this way, issues related to sustainability, the environment, waste management, recycling, and the scarcity of resources were allocated to the environmental category.

The second category identified in the study was the supply chain category. Ritzén and Sandström (2017) [57] used the supply chain category to present barriers to the CE, and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used the supply chain category to present the drivers of and barriers to the CE. In this sense, aspects from distribution channels, logistics, reverse logistics, and the potential to reduce channel dependence were allocated to the supply chain category.

The third category identified was the economic category. Gusmerotti et al. (2019) [10], Nohra et al. (2020) [29], Ababio and Lu (2023) [28] and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used the economic category to present only drivers of, only barriers to, and both (drivers and barriers), concerning the CE. In this way, aspects involving finance, sales, profitability, revenues, earnings, costs, accounting, raw material costs and prices, and the regulatory costs of environmental pollution and waste were allocated to the economic category.

The fourth category identified in our study was the information category. Nohra et al. (2020) [29] and Masi et al. (2017) [19] used the information category to present barriers to the CE, and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used the informational factors category to present the drivers of and barriers to the CE. In this way, aspects such as knowledge, information sharing, learning, training, and experiences were allocated to the information category.

The fifth category identified in the study was the legal category. Kumar et al. (2019) [30] and Ababio and Lu (2023) [28] used this category to present barriers to the CE in their article. Issues related to normativity, regulations, and legislation were allocated to the legal category.

The market was the sixth category identified in the article. Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53] and Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15] used the market category to present barriers to the adoption of the CE. Aspects embracing the external aspects of the organization, for instance, the environmental awareness of consumers, consumer preferences, market demands, and market trends were allocated to the market category.

The seventh category identified was the organizational category. Several authors used this category in their studies; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15] and Kumar et al. (2019) [30] used it to present barriers to the adoption of the CE, Jia et al. (2020) [20] and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used it to present drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE, and Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18] used it to present the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. Internal aspects related to companies and commercial institutions, such as competitiveness, performance indicators, organizational culture, company policy, human resources, the value and quality of products, raw materials and components, suppliers, partnerships, customer satisfaction, customer relationship, branding, and company image were allocated to the organizational category.

The public category was identified as the eighth category in this study. Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48] used public participation as a category to present the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. All issues related to the government, states, and municipalities, for instance, support, incentives, financial assistance, and public policies were allocated to the public category.

The ninth category identified in this study was the social category. Masi et al. (2017) [19] and Kumar et al. (2019) [30] and Ababio and Lu (2023) [28] used the social category to present barriers to the CE, and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used it to present the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. Aspects of society and community, involving job creation and reduction of the unemployment rate, population size, public health, safety, hygiene, social responsibility, social projects, public awareness, social recognition, and stakeholders were allocated to the social category.

The tenth category identified in this study was the technological category. Ritzén and Sandström (2017) [57], Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53], Nohra et al. (2020) [29], Masi et al. (2017) [19], Kumar et al. (2019) [30], and Ababio and Lu (2023) [28] used the technological category to present the barriers to the CE, and Tura et al. (2019) [26] used it to present the drivers of and barriers to the CE. Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48] used the technology category to present the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. Aspects related to science, technology, and innovation were allocated to the technological category.

Table 2 summarizes the authors who motivated the choice of each of the ten categories for the purpose of the final presentation of the study results. Table 2 also shows the authors that used other categories to work with the drivers of and barriers to the CE, and the authors who did not use any category in their studies to present the drivers of and barriers to the CE.

Table 2.

Motivation for choosing the categories of drivers and barriers.

4. Results and Discussion

In this chapter, the results of the analysis of the 53 articles on the drivers of and barriers to the CE that were analyzed for this study will be described and analyzed.

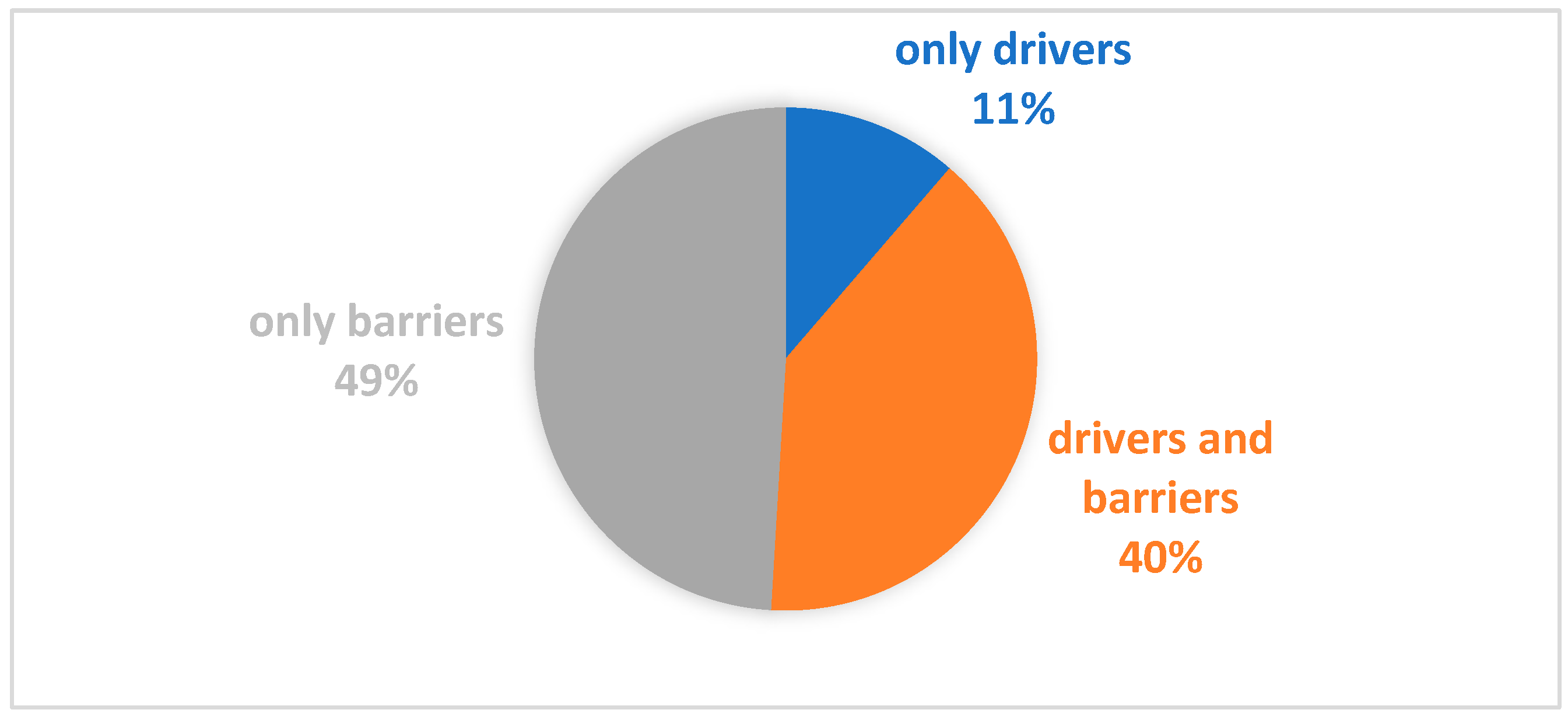

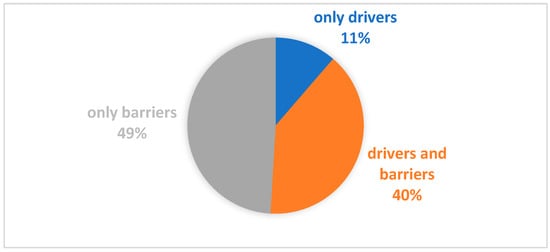

Of the total of 53 articles analyzed, 27 articles addressed drivers of the CE, and 47 articles addressed barriers to the CE. However, only 6 articles dealt only with drivers (11%), 26 articles dealt only with barriers (49%), and 21 articles dealt with both drivers and barriers (40%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Drivers and barriers article topic analysis.

The drivers and barriers extracted from the analyzed articles were categorized based on the categorization of drivers and barriers from the literature shown in Table 1. The ten categories identified and used to present the drivers that can help the implementation of the CE and the barriers disrupting its adoption are as follows:

- Environmental, which involves aspects related to sustainability, environment, waste management, recycling, and the scarcity of resources;

- Supply chain, which covers aspects involving the supply chain, distribution channels, logistics and reverse logistics, as well as, according to Tura et al. (2019) [26], drivers related to the potential to reduce channel dependence;

- Economic, which includes financial aspects, sales, profitability, revenues, earnings, costs, accounting, raw material costs and prices, and regulatory costs of environmental pollution and waste;

- Information, which involves aspects related to information, knowledge about the CE, information sharing, learning, training, and experience;

- Legal, which encompasses normative, regulatory, and legislative aspects, as well as the costs arising from these aspects;

- Market, which involves aspects of the market, that is, aspects external to the organization, for example, the environmental awareness of consumers, consumer preferences, market demands and market trends;

- Organizational, which involves managerial aspects and aspects related to companies and commercial institutions, that is, the internal aspects of the company/organization such as competition and competitiveness, performance indicators, organizational culture, company policy, environmental aspects (such as environmental collaboration of customers and suppliers, reduction of the environmental impact of the company and processes), aspects regarding ownership, aspects of management and personnel department (such as leadership, employees, workers, and shareholders), aspects regarding the product (product value and quality), raw materials and components, suppliers, partnerships, customers (customer satisfaction and customer relationship), branding, and company image;

- Public, which encompasses aspects regarding the government, states, and municipalities, such as, for example, their support, incentive, financial assistance, and public policies;

- Social, which encompasses aspects of society and the community, involving job creation and reduction of the unemployment rate, population size, public health, safety, hygiene, social responsibility, social projects, public awareness, social recognition, and stakeholders;

- Technological, which involves aspects related to science and technology, technological innovation, and technical aspects, as well as the costs arising from these technologies.

It should be noted that the dividing line between some categories is very tenuous. When this occurred, the authors used the conceptual definition of the category as a criterion.

4.1. Drivers to the Circular Economy

A number of studies have pointed out drivers of the adoption of the CE in order to encourage, motivate, facilitate, and drive companies to adopt CE, and different approaches were used. In their study, Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18] examined the drivers in order to understand the motivational factors for implementing the CE in the supply chain. Moktadir et al. (2018) [27] and Hart et al. (2019) [22] refer to a driver as a facilitator in their studies. Motivations for CE practices and facilitating factors for the implementation of circular practices are raised in the study by Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]. In the study by Jabbour et al. (2020) [23], CE motivators and CE drivers were considered to be synonymous. Finally, in their study, Xue et al. (2010) [24] address methods that drive the development of the CE, and Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73] presented reasons to implement CE.

Based on this, it was observed that there is no clear-cut definition of drivers in the literature. What is known is that all expressions and nomenclatures used in the literature when it comes to drivers express driving forces leading companies to adopt the CE. The boundaries between the definitions are not clear; there are overlapping areas between the concepts. For the purposes of this study, drivers are therefore defined as forces that motivate or encourage companies to adopt CE.

There were several areas in which CE drivers were studied in the literature. Table 3 presents the contexts and sectors in which the papers were developed.

Table 3.

Contexts of application of studies of the drivers of the CE.

In addition, the studies’ geographic contexts cover a significant range of countries around the world. Continents, countries, and authors are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Countries and regions from which articles on CE drivers and barriers came.

Based on the analysis of data from articles that contained drivers of the adoption of the CE, the drivers were categorized into the ten categories proposed for this study. As a result, a list of 160 drivers was obtained and categorized. Some of these drivers will be presented below.

- (a)

- Environmental drivers support the adoption of the CE, as there is great concern about environmental impacts and the state of the environment [20], the scarcity of resources [26], and global warming and climate change [18]. The CE can act as a solution to these problems, helping to minimize environmental impact [73], reduce waste [30], and develop sustainability [22].

- (b)

- For supply chains, the adoption of the CE brings improvements to the entire chain [27]. For example, it may improve material efficiency and energy use [18], and increase chain transparency [26] and chain engagement [22].

- (c)

- Considering the economic category, one of the main drivers identified in the literature that motivates companies to adopt the CE was cost reduction [45]. By adopting the CE, gains in resource efficiency are made [12], and new value streams are created using byproducts and waste, thus giving companies a new source of revenue and minimizing costs related to the treatment and disposal of waste [19]. In addition, the regulatory costs of environmental pollution and waste are avoided [19]. Finally, the CE generates economic growth for companies [49].

- (d)

- Information drivers help the implementation of the CE, providing information [20], training and education [27], and knowledge exchange [58].

- (e)

- Considering the category of legal drivers, the existence of laws and regulations regarding CE [23] was a very important aspect found in the literature that helps companies to adopt CE.

- (f)

- As market drivers, awareness of environmental issues among consumers [73], customer awareness of green initiatives [20], and the preference and demand for circular products [23] drive the adoption of the CE.

- (g)

- There are several organizational drivers identified in the literature that drive companies to adopt the CE: gains in market share and competitiveness [10,20], environmental collaboration with customers and suppliers [27], companies’ willingness to adopt circulars [72], employee engagement and motivation [20], increased product value and quality [44], improving relationships with customers, building loyalty, and increasing their satisfaction [10], the promotion of the company’s reputation, its brand and improving the corporate image [19], the collaboration between organizations and the enlarging of the network and partnerships [50], and the stability of the company [44]. All of these aspects motivate companies to adopt the CE.

- (h)

- Public drivers motivate the adoption of the CE due to the support of the government and public institutions, whether in the form of financial, tax, or fiscal support, the waste collection system, or public policies [21,49].

- (i)

- Social drivers support the adoption of the CE due to the possibility of generating jobs [33], concern for public health [30], social awareness [45], community pressure to adopt the CE [27], and stakeholder pressure for sustainable consumption [51].

- (j)

- In the category of technological drivers, investment in science and technology for the CE’s implementation is considered a very important aspect [48], in addition to the use of new and state-of-the-art technologies [23].

The categories of drivers for the adoption of the CE and the authors can be seen in Appendix A.

4.2. Barriers to the Circular Economy

Although on the one hand, a series of studies have pointed out drivers for the adoption of the CE to encourage, motivate, facilitate, and encourage companies to adopt a circular process, a number of barriers to the adoption of the CE were also found in the literature, expressing forces opposing the CE’s implementation, inhibiting or barring the CE’s development. Different approaches were used by authors in the literature regarding the barriers to the adoption of the CE. According to Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33], barriers are factors that hinder the implementation of the CE’s practices. Ranta et al. (2018) [51] consider CE barriers to be difficulties face in the CE’s implementation. Kumar et al. (2019) [30] and Masi et al. (2017) [19] treat barriers as inhibitors to the CE’s implementation, whereas Rajput and Singh (2019) [74] address challenges involved in the implementation of the CE.

Based on this, it is observed that there is also no clear-cut definition of barriers in the literature. However, all expressions and nomenclatures used in the literature when it comes to barriers express forces that oppose the adoption of the CE. The boundaries between the definitions are not clear; there are overlapping areas between the concepts. For the purposes of this study, barriers are considered to be obstacles that hinder, or even prevent, the implementation of the CE.

Several sectors were the focus of the studies of the barriers to the adoption of the CE in the literature. Based on the literature review of the articles that deal with barriers, we observed the application of studies in the contexts and sectors presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Contexts of application of studies of barriers to the CE.

It was also observed that studies related to barriers were applied in a significant number of countries around the world. Table 4 presents these continents, countries, and authors.

From the analysis of data from articles that contained barriers to the adoption of the CE, barriers were grouped according to the ten categories proposed for this study. As a result, a list of 430 barriers was obtained. Some of these barriers will be presented below.

- (a)

- Environmental barriers can hamper the adoption of the CE due to the difficulty of validating, verifying, and predicting environmental pollution and all environmental effects and impacts [13]; the lack of benefits in relation to environmental sustainability, and uncertainty about potential environmental benefits [70]; the low level of reuse, recycling, and recovery of waste [52]; inefficiency in waste management [67]; the limited availability and quality of recycling materials [19]; and the underdeveloped waste infrastructure, which is to take components back for reuse [55]. There is also an informal sector tradition that collects recyclables and food waste (China), and textile waste [52].

- (b)

- Within supply chains, the adoption of the CE may be hampered due to costs, lack of priority, lack of employee skills, lack of enthusiasm and leadership from managers [18], lack of customer awareness [54], the fragile return and collection system [17], the lack of reverse logistics infrastructure [52], the lack of collaboration with stakeholders in the supply chain in CE initiatives [54], and the lack of suitable partners in supply chains [30].

- (c)

- Considering the economic category, some aspects can obstruct the implementation of the CE, such as high initial investment costs [22,28,70]; high production costs, management costs, and planning costs [29]; the low price of virgin raw materials compared to recycled/reused materials [52]; the uncertain profits and returns [28,45], and uncertain economic and fiscal benefits [71]; the lack of funding [15,28]; the lack of working capital [45]; the lack of financial resources [73]; financial risk [16]; and the lack of economies of scale [70].

- (d)

- Some aspects of the information category can obstruct the implementation of the CE, given that there is a lack of training and education of the people involved in the chain [48], a lack of knowledge and skills about CE [15], an abundance of poor data and a lack of data quality [29], and a lack of information [20].

- (e)

- Regarding the legal category, the lack of clarity or lack of support for the CE in the form of laws, norms, and rules becomes a major obstacle to the implementation of the CE. For example, there is a lack of legislation for recycling [51], waste management [55], the environment [48], green production [48], and laws that are specific to the CE’s implementation [18]. There is also low regulatory support for increasing reuse activities [51], and bureaucratic difficulty in enforcing legislation on the sustainability (e.g., waste, water) of companies [21]. Furthermore, there are still laws and regulations that are opposed to CE solutions [13].

- (f)

- Market barriers can hamper the CE’s implementation, mainly considering two aspects: demand and consumers. The demand for circular products and processes is still restricted [29] and unclear [15]. In addition, there is a lack of demand for remanufactured products due to their appearance [30]. Regarding the consumer, there is a lack of interest in circular processes and products [53] and a lack of environmental awareness [73]. In addition, customers have a negative perception of the quality of remanufactured products [56], preferring new products and materials over reused or remanufactured ones [67].

- (g)

- With regard to organizational barriers, it was identified that the lack of metrics, measurements, and a system with indicators and a method of performance evaluation can hinder the implementation of the CE [52], in addition to the fear of possible risks arising from the implementation of the CE [76] and the lack of collaboration between business functions and departments [17]. There is a business culture that operates a linear system [53] and maintains conservatism in current practices [22] and resistance to change [70], thus causing cultural conflicts [26]. Companies’ own cultures do not favor the adoption of the CE [53], and their organizational structures make it difficult to implement the CE [18]. Regarding the managerial level of the organization, there is a lack of commitment [70], will [30], environmental awareness [19], support, and collaboration on the part of management [73], making the adoption of the CE difficult. Regarding the raw material, there is volatility in terms of quantity and availability [17] and a low quality of recovered used parts [56] negatively impacting the adoption of the CE. The difficulty of establishing partnerships is also an aspect that can hinder the implementation of the CE; there may be, for example, lack of suitable partners [30], difficulty in business-to-business (B2B) cooperation [78], and lack of a shared vision and willingness to collaborate with chain partners [52]. It takes time to build new partnerships and mutual trust [15]. Organizations are also faced with the challenge of a lack of qualified personnel to work with the CE and related areas (environmental, remanufacturing, reuse of products and components) [44,46]. Regarding the company’s products, it is difficult to maintain quality throughout the product’s life cycle, because returned materials may cause low quality in recycled products [52]. It is also difficult for companies to manage products made from reclaimed materials [18].

- (h)

- Regarding the public category, the lack of incentives and support (industrial and financial) from the government is one of the main obstacles to the implementation of the CE identified in the literature [24,63]. In addition, existing recycling policies are ineffective in achieving high-quality recycling, thus hampering the development of the CE [18]. Moreover, there is a lack of public awareness about the CE [24], and public incentives regarding the CE are misaligned, complex, and confusing [45].

- (i)

- The category of social barriers can hamper the adoption of the CE due to the low involvement of society in circular actions and practices [67]; the lack of a global consensus on CE [53]; the lack of awareness in society about circularity [76]; the linear mindset rooted in society [58]; the values, norms, lifestyles, and current social practices; a lack of cultural diversity, and social ignorance about the resource cycle [29].

- (j)

- Technological barriers can impede the development of the CE due to the lack of technological systems [20]; lack of technology transfer [54]; lack of appropriate technologies for the CE [46]; lack of technical support [45,70]; insufficient technical resources [46]; weak demand and acceptance of environmental technologies [54], and the lack of skills and technical capacities of workers [78]. In addition, as there is a need for investment in technology for the adoption of the CE, the costs arising from this investment may also become an obstacle to the CE’s implementation [74].

The categories of barriers to the adoption of the CE and the authors can be seen in Appendix A.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Contributions and Implications

This study aimed to identify and categorize drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE through a systematic literature review. The study’s conclusion will be presented based on 53 analyzed articles. The results of the study show that there are more articles in the literature reflecting barriers to the adoption of the CE than those reflecting drivers of its adoption. Consequently, the study indicates that in the literature, there are more barriers to than drivers of the adoption of the CE. Thus, it was observed that the literature demonstrates a greater concern with what bars, prevents, or hinders companies and society implementing circular behavior; this circular behavior is necessary, considering the current increasing concern about the scarcity of resources in the environment.

Furthermore, it was observed that there are different contexts and sectors in which the analyzed studies were applied, and a significant range of countries and regions around the world were involved. The region in which the largest number of searches was observed was Europe. Corroborating this, in the last 50 years, there has been an intense debate on energy policies and issues related to the environment among the countries of the European Union [80], culminating in 2019 with the affirmation of commitments to face the challenges of sustainability by adopting the European Green Deal (EGD), a set of initiatives for environmental protection whose main objective is to promote sustainable development strategies focused on energy emissions and the mitigation of climate change [81]. Furthermore, these European Green Deal policies can be incorporated into economic models that promote sustainable development, such as the CE [82].

Finally, the authors of 19 of the articles analyzed in this paper used some categorization to present the drivers and barriers in their studies. Following this idea, the drivers and barriers listed in the literature review were grouped according to ten categories identified and proposed for this study. The ten categories of drivers that can help the implementation of the CE and the barriers disrupting its adoption are presented as follows.

The first category defined in the study, the environmental category, looks at environmental aspects related to sustainability, waste management, recycling, and the scarcity of resources [26]. Concern regarding its environmental impact and concern for environmental sustainability are subjects discussed in the literature [1,20].

The second category identified was the supply chain category, which involves the aspects of the supply chain, distribution channels, logistics, and reverse logistics [57]. It is important to pay close attention to the supply chain as a whole in order to succeed in the CE’s development. CE strategies are crucial to restructure the take-make-discard model through the active participation of all actors in the supply chain [83].

The economic category was the third category defined in the study, and covers financial aspects, sales, profitability, revenues, earnings, costs, accounting, the costs of raw materials, and the regulatory costs of environmental pollution and waste [29]. Lack of financial resources is a major limitation for companies in adopting the CE [73]. This could be dealt with by government support and public policies to achieve the CE, as suggested by Arthur et al. (2023) [2].

The fourth category identified was the information category, which considers aspects related to information, CE knowledge, information sharing, learning, training, and experience [19]. Everyone involved in the circular chain must have the necessary information to develop the CE successfully. One of the goals of the 12th SDG of the 2030 Agenda (2015) [42] is to ensure that people have relevant information and awareness about sustainable development.

The fifth category identified was the legal category, looking at normative and regulatory aspects, and their costs [30]. The lack of laws supporting CE practices is one of the major obstacles to the implementation of the CE [51,55]. Policymakers should attend to developing laws that could incentivize companies to adopt the practices of the CE.

The market category was the sixth category defined for the present study. External aspects of the organization, such as consumer environmental awareness, consumer preference, market demands, and trends, constitute this category [15]. There has been an increase in environmental awareness and concern for the environment on the part of consumers, thus generating an increase in demand for circular products. While joining the CE encourages the emergence of new demands for services and new potential markets [8], companies’ interest in adopting the CE is increasing.

The seventh category identified in this study is the organizational category, which considers aspects related to companies and commercial institutions, i.e., internal company/organizational features such as competition and competitiveness, performance indicators, organizational culture, company policy, the environmental aspects of the company, aspects related to property, the management and personnel department, products, raw materials, components, suppliers, partnerships, customers, branding, and company image [18]. The benefits arising from the implementation of the CE for companies are numerous, but on the other hand, the challenges are also great. The adoption of the CE generates competitive advantages for circular companies [10,20]; thus, the CE has attracted interest from the business community wanting to work on sustainable development [8].

The public category was the eighth category defined in the study, involving aspects from the government, states, and municipalities, via the government’s support, encouragement, financial aid, and public policies [48]. The lack of incentives and industrial and financial support from the government is one of the main obstacles to the implementation of the CE identified in the literature [29,56,73]. It is thus observed that public involvement is fundamental for the development of the CE. Financial resources are scarce, making implementing CE unfeasible for many companies [46,70], especially small and medium-sized companies. Through financial, tax, and fiscal support, and public policy, the adoption of the CE can be encouraged. In accordance with this, Arthur et al. (2023) [2] mentioned that a blend of government policies is an effective means of achieving a CE.

The ninth category identified in the study is the social category. This category involves society and community aspects, such as job creation and the reduction of the unemployment rate, population size, public health, safety, hygiene, social responsibility, social projects, and public awareness [30]. Increased awareness of social responsibility [1] should be harnessed as a driver for new circular business opportunities and the CE’s development.

Finally, the tenth category defined in the study is the technological category, which considers science, technology, and technical aspects [53]. Considering that we live in a technological era of digitization and great technological developments, companies could embrace these aspects to help them in the development of the CE. It is suggested that the development of specific technologies will be necessary for the development of the CE. In this sense, the 2030 Agenda (2015) [42] points to the goal of the 12th SDG, supporting developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacities in pursuit of more sustainable patterns of production and consumption.

A summary of the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the circular economy.

It is important to highlight the multilevel approach within which these categories were constructed. Even though it was not the focus of this study, allocation at the micro, meso and macro levels is evident, following the findings of Ababio and Lu (2023) [28], which reinforce the current consensus that the CE should be discussed using a multilevel approach.

First, this study contributes by extending the body of knowledge on the CE, helping to integrate the existing literature and develop a comprehensive theoretical framework for guiding future research, as mentioned by Zhang et al. (2022) [4]. Due to the assessment of an extensive number of articles, a list of 160 drivers of and 430 barriers to the adoption of the CE was obtained. Having these drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE listed in the literature, it is possible to gain an in-depth understanding of the CE’s context, thus providing researchers and practitioners with prior information about the realities that they will face. This will also allow companies and governments to work toward the CE’s implementation, helping the transition from a linear economy to a CE, which is more efficient in terms of resources and will help us to advance toward sustainable economies [14]. The transition from a linear economy to a CE is a matter of extreme relevance in the pursuit of more sustainable development [84].

In accordance with this, the second contribution of this study is to bring about sustainable benefits for companies and society, by making them aware of aspects that foster the CE and aspects that make the implementation of the CE difficult. Substantially reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse, and achieving sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources are some of the targets of the 12th SDG addressed in the 2030 Agenda (2015) [42], ensuring standards of sustainable production and consumption by the year 2030 (2030 Agenda, 2015). In this sense, the CE can be considered a promising concept for sustainable development [8]. Additionally, Ali et al. (2023) [35] mention circular economy-centric education being the solution to the social, economic, and environmental problems stemming from climate change. Moreover, green technologies, through the optimization of the use of resources, reduction of waste, and reduction of the demand for new resources, promote the development of green products and services, helping to reduce the environmental impact of consumption [35].

Third, the presentation of an extensive literature review enabled a broader view and a categorization of the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE. These contributions are important to help companies develop a CE and encourage them to implement it. Additionally, the literature review contributes to helping governments to gain knowledge, in order to work on public policy implementation and actions to foster the CE’s adoption. According to Schraven et al. (2019) [85], government incentives, such as research funds or stimulating legislation, should be created. Yazdanpanah et al. (2019) [86] support policymaking and fine-tuning the regulations that will foster the transition to a CE; for instance, due to a lack of regulations, firms may face no prohibition of the disposal of some particular (hazardous) wastes, and may have no incentives in the case of substituting some of their raw materials with reusable waste inputs. In this sense, the authors suggest that policymakers could introduce monetary incentives to foster such practices [86]. Furthermore, the study results would facilitate practitioners’ understanding of the drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE, that they might handle them effectively.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

The main limitations of this research refer to the number of databases used. Only the Scopus database was used to collect data. We suggest that future studies also use other databases.

Even though this review was quite comprehensive, the search strategy used only the most consolidated terms in the literature, and may have left out some articles that used other nomenclatures. Thus, it is suggested that future studies use not only consolidated terms (for example, “circular economy”), but also different combinations of keywords that may be synonymous, such as, for example, “circular practices”, “circularity”, and “circular model”.

Although some studies have discussed the circular economy in specific regions, e.g., in the Baltic region [87] and Central and Eastern European countries [88], the present study did not aim to discuss drivers and barriers in different regions or countries. However, due to the importance of countries having different behaviors, it is suggested that future studies take these local idiosyncrasies into account, testing the current categorization.

The analysis showed that there are some aspects of categories such as social, for example, hygiene, public health, and safety, that are not explored in depth in the literature. Thus, future research could identify the less explored categories in the literature and explore them, thereby leading to new frontiers.

This research is part of a research project focused on understanding how to promote an ideal structure of the CE in the organic products sector. The next step of this research is to validate the drivers and barriers that apply to producers and consumers in this sector. At the same time, it will be possible to verify if this general proposal can be applied to different sectors and markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and D.C.-D.-M.; methodology, C.P., D.C.-D.-M. and C.S.L.S.; validation, C.P., D.C.-D.-M. and C.S.L.S.; formal analysis, C.P.; investigation, C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.; writing—review and editing, C.P., D.C-D-M. and C.S.L.S.; supervision, C.P.; funding acquisition, C.S.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Categories of drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE and the authors.

Table A1.

Categories of drivers of and barriers to the adoption of the CE and the authors.

| Barriers Authors | Category | Drivers Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Mahpour (2018) [67]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Milios et al. (2019) [55]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]. | ENVIRONMENTAL | Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Hartley et al. (2020) [11]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]. |

| Ritzén and Sandström (2017) [57]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Jaeger and Upadhyay (2020) [78]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]; Werning and Spinler (2020) [17]. | SUPPLY CHAIN | Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; Ritzén and Sandström (2017) [57]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Ghisellini et al. (2018) [66]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53]; Mahpour (2018) [67]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Garcés-Ayerband et al. (2019) [67]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Milios et al. (2019) [55]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Scarpellini el al. (2019) [75]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jaeger and Upadhyay (2020) [78]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Kanters (2020) [16]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]. | ECONOMIC | Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44], Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Gue et al. (2019) [72]; Gusmerotti et al. (2019) [10]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Hartley et al. (2020) [11]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Robaina et al. (2020) [12]; Ababio and Lu (2023) [28]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Bolger and Doyon (2019) [68]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Rajput and Singh (2019) [74]; Galvão et al. (2020) [63]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jaeger and Upadhyay (2020) [78]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]; Ozkan-Ozen et al. (2020) [79]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]. | INFORMATION | Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Gue et al. (2019) [72]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Xue et al. (2010) [24]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Garcés-Ayerband et al. (2019) [67]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Milios et al. (2019) [55]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Rajput and Singh (2019) [74]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Singh and Giacosa (2019) [76]; Tseng et al. (2019) [77]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; García-Quevedo et al. (2020) [14]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Kanters (2020) [16]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Mura et al. (2020) [21]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]; Shao et al. (2020) [56]; Werning and Spinler (2020) [17]. | LEGAL | Xue et al. (2010) [24]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; De Mattos and De Albuquerque (2018) [50]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Gue et al. (2019) [72]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Hartley et al. (2020) [11]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Ababio and Lu (2023) [28]. |

| Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53]; Mahpour (2018) [67]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Camacho-Otero (2019) [69]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Milios et al. (2019) [55]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Scarpellini el al. (2019) [75]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Singh and Giacosa (2019) [76]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Kanters (2020) [16]; Mura et al. (2020) [21]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]; Shao et al. (2020) [56]; Werning and Spinler (2020) [17]. | MARKET | De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Gue et al. (2019) [72]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; Ritzén and Sandström (2017) [57]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Ghisellini et al. (2018) [66]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53]; Mahpour (2018) [67]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Chang and Hsieh (2019) [25]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Garcés-Ayerband et al. (2019) [67]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Milios et al. (2019) [55]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Rajput and Singh (2019) [74]; Scarpellini el al. (2019) [75]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Singh and Giacosa (2019) [76]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Galvão et al. (2020) [63]; García-Quevedo et al. (2020) [14]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jaeger and Upadhyay (2020) [78]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Kanters (2020) [16]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Mura et al. (2020) [21]; Ozkan-Ozen et al. (2020) [79]; Shao et al. (2020) [56]; Werning and Spinler (2020) [17]. | ORGANIZATIONAL | Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Mattos and De Albuquerque (2018) [50]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Gue et al. (2019) [72]; Gusmerotti et al. (2019) [10]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Hartley et al. (2020) [11]; Mura et al. (2020) [21]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Xue et al. (2010) [24]; Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Ghisellini et al. (2018) [66]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Mahpour (2018) [67]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Bolger and Doyon (2019) [68]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Galvão et al. (2020) [63]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Mura et al. (2020) [21]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]; Shao et al. (2020) [56]. | PUBLIC | Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Xue et al. (2010) [24]; Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Mattos and De Albuquerque (2018) [50]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Bolger and Doyon (2019) [68]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Chang and Hsieh (2019) [25]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Piyathanavong et al. (2019) [73]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Mura et al. (2020) [21]; Robaina et al. (2020) [12]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; Galvão et al. (2018) [63]; Kirchherr et al. (2018) [53]; Mahpour (2018) [67]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Chang and Hsieh (2019) [25]; Scarpellini el al. (2019) [75]; Singh and Giacosa (2019) [76]; Tseng et al. (2019) [77]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Guldmann and Huulgaard (2020) [15]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]. | SOCIAL | Xue et al. (2010) [24]; Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Ranta et al. (2018) [51]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Bolger and Doyon (2019) [68]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Gue et al. (2019) [72]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Ababio and Lu (2023) [28]. |

| Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Xue et al. (2010) [24]; Ilić and Nikolić (2016) [49]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Govindan and Hasanagic (2018) [18]; Mangla et al. (2018) [54]; Ormazabal et al. (2018) [46]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Campbell-Johnston et al. (2019) [58]; Farooque et al. (2019) [70]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Rajput and Singh (2019) [74]; Šebo et al. (2019) [47]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Dieckmann et al. (2020) [13]; Galvão et al. (2020) [63]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Jaeger and Upadhyay (2020) [78]; Jia et al. (2020) [20]; Kazancoglu et al. (2020) [52]; Nohra et al. (2020) [29]; Ozkan-Ozen et al. (2020) [79]. | TECHNOLOGICAL | Geng and Doberstein (2008) [48]; Masi et al. (2017) [19]; De Jesus and Mendonça (2018) [45]; Moktadir et al. (2018) [27]; Agyemang et al. (2019) [44]; Barbaritano et al. (2019) [33]; Chang and Hsieh (2019) [25]; Hart et al. (2019) [22]; Kumar et al. (2019) [30]; Tura et al. (2019) [26]; Hartley et al. (2020) [11]; Jabbour et al. (2020) [23]; Ababio and Lu (2023) [28]. |

References

- Flores, P. Latin America. In The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2022; Willer, H., Trávnícek, J., Meier, C., Eds.; Fibl & Ifoam—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2022; pp. 272–274. Available online: https://www.organic-world.net/yearbook/yearbook-2022.html (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Arthur, E.E.; Gyamfi, S.; Gerstlberger, W.; Stejskal, J.; Prokop, V. Towards Circular Economy: Unveiling Heterogeneous Effects of Government Policy Stringency, Environmentally Related Innovation, and Human Capital within OECD Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilho, F. Sustentabilidade Ambiental, Consumo e Cidadania; Cortez: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P. Circular economy and the food sector: A systematic literature review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M.; Ruzzier, M.K.; Sučić, B.; Soltwisch, B. Challenges of demographic changes and digitalization on eco-innovation and the circular economy: Qualitative insights from companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 396, 136439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The circular economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velenturf, A.P.; Purnell, P. Principles for a sustainable circular economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1437–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C. Circular economy innovations, growth and employment at the firm level: Empirical evidence from Germany. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmerotti, N.M.; Testa, F.; Corsini, F.; Pretner, G.; Iraldo, F. Drivers and approaches to the circular economy in manufacturing firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, K.; van Santen, R.; Kirchherr, J. Policies for transitioning towards a circular economy: Expectations from the European Union (EU). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaina, M.; Villar, J.; Pereira, E.T. The determinants for a circular economy in Europe. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 12566–12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, E.; Sheldrick, L.; Tennant, M.; Myers, R.; Cheeseman, C. Analysis of Barriers to Transitioning from a Linear to a Circular Economy for End of Life Materials: A Case Study for Waste Feathers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quevedo, J.; Jové-Llopis, E.; Martínez-Ros, E. Barriers to the circular economy in European small and medium-sized firms. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2450–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldmann, E.; Huulgaard, R.D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanters, J. Circular Building Design: An Analysis of Barriers and Drivers for a Circular Building Sector. Buildings 2020, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werning, J.P.; Spinler, S. Transition to circular economy on firm level: Barrier identification and prioritization along the value chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, D.; Day, S.; Godsell, J. Supply Chain Configurations in the Circular Economy: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Yin, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, X. The circular economy in textile and apparel industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Zanni, S. Circular economy in Italian SMEs: A multi-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Adams, K.; Giesekam, J.; Tingley, D.D.; Pomponi, F. Barriers and drivers in a circular economy: The case of the built environment. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Seuring, S.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jugend, D.; Fiorini, P.D.C.; Latan, H.; Izeppi, W.C. Stakeholders, innovative business models for the circular economy and sustainable performance of firms in an emerging economy facing institutional voids. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.; Chen, X.-P.; Geng, Y.; Guo, X.-J.; Lu, C.-P.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Lu, C.-Y. Survey of officials’ awareness on circular economy development in China: Based on municipal and county level. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Hsieh, S.-H. A Preliminary Case Study on Circular Economy in Taiwan’s Construction. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 225, 012069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking circular business: A framework of barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Rahman, T.; Rahman, M.H.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K. Drivers to sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy: A perspective of leather industries in Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1366–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababio, B.K.; Lu, W. Barriers and enablers of circular economy in construction: A multi-system perspective towards the development of a practical framework. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 41, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohra, C.G.; Pereno, A.; Barbero, S. Systemic Design for Policy-Making: Towards the Next Circular Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sezersan, I.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Gonzalez, E.D.; Al-Shboul, M.A. Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: Benefits, opportunities and barriers. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1067–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.K.; Govindan, K. Barriers to the adoption of circular economy practices in Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises: Instrument development, measurement and validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 351, 131389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G.; Tornese, F. Evaluating the adoption of circular economy practices in industrial supply chains: An empirical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaritano, M.; Bravi, L.; Savelli, E. Sustainability and Quality Management in the Italian Luxury Furniture Sector: A Circular Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M. Sustainable Development Goals: A Regional Overview Based on Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Appolloni, A.; Cavallaro, F.; D’adamo, I.; Di Vaio, A.; Ferella, F.; Gastaldi, M.; Ikram, M.; Kumar, N.M.; Martin, M.A.; et al. Development Goals towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Yang, N.-H.N.; Schulze-Spüntrup, F.; Heerink, M.J.; Hartley, K. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy (Revisited): An Analysis of 221 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 194, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friant, M.C.; Vermeulen, W.J.; Salomone, R. A typology of circular economy discourses: Navigating the diverse visions of a contested paradigm. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnem, S.; Pereira, S.C.F. Rumo à Economia Circular: Sinergia Existente entre as Definições Conceituais Correlatas e Apropriação para a Literatura Brasileira. Rev. Eletrônica Ciência Adm. 2019, 18, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Cities and Circular Economy for Food. 2019. Available online: ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A Solution to Build Back Better: The Circular Economy. 2020. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/emf-jointstatement.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Agenda 2030. 2015. Agenda 2023 Para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/91863-agenda-2030-para-o-desenvolvimento-sustentavel (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Corvellec, H.; Stowell, A.F.; Johansson, N. Critiques of the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, M.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Khan, S.A.; Mani, V.; Rehman, S.T.; Kusi-Sarpong, H. Drivers and barriers to circular economy implementation. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 971–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in transition? drivers and barriers in the eco-innovation road to the circular economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Puga-Leal, R.; Jaca, C. Circular Economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebo, J.; Kádárová, J.; Malega, P. Barriers and motives experienced by manufacturing companies in implementing circular economy initiatives: The case of manufacturing industry in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Council on Technologies of Environmental Protection (ICTEP), Starý Smokovec, Slovakia, 23–25 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Doberstein, B. Developing the circular economy in China: Challenges and opportunities for achieving ‘leapfrog development’. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.; Nikolić, M. Drivers for development of circular economy—A case study of Serbia. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mattos, C.A.; De Albuquerque, T.L.M. Enabling factors and strategies for the transition toward a circular economy (CE). Sustainability 2018, 10, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Ritala, P.; Mäkinen, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]