The Role of Metropolitan Areas in the Spatial Differentiation of Food Festivals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Areas in Spatial Development

2.2. Food Festivals—Location and Importance

3. Research Materials and Methods

4. Autocorrelation of Food Festivals in Poland

5. Kernel Estimation of Food Festivals—A Case Study

- m—the random sample size,

- n—dimensions of the space (event coverage),

- h—positive real number (smoothing parameter),

- K—a function satisfying the conditions:

- Centrifugal impact—when the kernel is very close to the center of the polygon, i.e., in the centroid of the administrative voivodship area.

- Peripheral impact—when the kernel is located peripherally within the polygon but not on the border of the voivodship administrative area.

- Extreme peripheral impact—when the kernel is located exactly at the polygon’s boundary.

6. Discussion

- With regard to the impact on the development of economic management centers, what plays a vital role in the development of a given center and region are major companies generating multiplier effects by attracting additional specialized entities.

- With regard to the shaping of the transport system, it is worth considering a change in the course of the Berlin-Warsaw-Minsk-Moscow corridor, which would strengthen the position of Bialystok and Hrodna, thus increasing exposure for the Masurian region [74].

- In terms of regional development, there is a noticeable lack of detailed studies on changes in the settlement system and in demographic processes, including concentration and depopulation.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hjalager, A.M.; Kwiatkowski, G. Transforming rural foodscapes through festivalization: A conceptual model. J. Gastron. Tour. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Arcodia, C. The role of regional food festivals for destination branding. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, G.E.D.; Heath, E.; Alberts, N. The role of local and regional food in destination marketing: A South African situation analysis. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2003, 14, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Hjalager, A.M.; Ossowska, L.; Janiszewska, D.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. The entrepreneurial orientation of exhibitors and vendors at food festivals. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, K.; Mykletun, R.J. Exploring the success of the Gladmatfestival (the Stavanger Food Festival). Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parysek, J.J. Fundamentals of Local Economy; UAM Scientific Publishers: Poznan, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brol, R. Management of Local Development—A Case Study; Ed. Academy of Economics; Oskar Lange We Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Budner, W. Location of Enterprises. Economic, Spatial and Environmental Aspects; Publishing House of the Poznan University of Economics: Poznan, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, R. Spatial Economy; Scientific Publishers PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kuciński, K. Economic Geography; SGH Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zarębski, P.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Oklevik, O. Tourism Investment Gaps in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maik, W. Basics of Urban Geography; Nicolaus Copernicus University Publishing House: Toruń, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.H. Celebrating asparagus: Community and the rationally constructed food festival. J. Am. Cult. 1997, 20, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrett, R. Making sense of how festivals demonstrate a community’s sense of place. Event. Manag. 2003, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I.; Mcmahon-Beattie, U.; Findlay, K.; Goh, S.; Tieng, S.; Nhem, S. Future proofing the success of food festivals through determining the drivers of change: A case study of wellington on a plate. Tour. Anal. 2021, 26, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. The strategic use of events within food service: A case study of culinary tourism in Macao. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering, Nanjing, China, 26–28 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohi, Z.; Wong, J.J. A study of food festival loyalty. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2013, 5, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, A.; Varley, P. Food tourism and events as tools for social sustainability? J. Place. Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Racz, A.; Mijoč, J. Local food festival: Towards a sustainable food tourism experience. In Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific Symposium Economy of Eastern Croatia—Vision and growth, Osijek, Croatia, 24–26 May 2018; pp. 838–844. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.; Di-Clemente, E.; Mogollón, J. Food Festivals and the Development of Sustainable Destinations. The Case of the Cheese Fair in Trujillo (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Li, Y. Analyzing the effects of urban food festival: Place theory approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albala, K. Food Fairs and Festivals. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues; Albala, K., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 565–569. [Google Scholar]

- Baldy, J. Framing a Sustainable Local Food System—How Smaller Cities in Southern Germany Are Facing a New Policy Issue. Sustainability 2019, 6, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; Kwiatkowski, G. Relational Food Festivals: Building Space for Multidimensional Collaboration Among Food Producers. In Planning and Managing Sustainability in Tourism; Farmaki, A., Altinay, L., Font, X., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arcodia, C.; Whitford, M. Festival attendance and the development of social capital. J. Conv. Event. Tour. 2006, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Oklevik, O.; Hjalager, A.-M.; Maristuen, H. The assemblers of rural festivals: Organizers, visitors and locals. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, B.; Halkier, H. Mussels, Tourism and Community Development: A Case Study of Place Branding through Food Festivals in Rural North Jutland, Denmark. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1587–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G. The Multifarious Capacity of Food Festivals in Rural Areas. J. Gastron. Tour. 2018, 3, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollows, J.; Jones, S.; Taylor, B.; Dowthwaite, K. Making sense of urban food festivals: Cultural regeneration, disorder and hospitable cities. J. Policy Res. Tour. 2014, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D. Urban gastronomic festivals—Non-food related attributes and food quality in satisfaction construct: A pilot study. J. Conv. Event. Tour. 2016, 17, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębski, P.; Zwęglińska-Gałecka, D. Mapping the Food Festivals and Sustainable Capitals: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K. Festivals post COVID-19. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Dhoundiyal, H.; Choudhury, R. Events Tourism in the Eye of the COVID-19 Storm: Impacts and Implications. In Event Tourism in Asian Countries: Challenges and Prospects, 1st ed.; Arora, S., Sharma, S., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Janeczko, B.; Mules, T.; Ritchie, B. Estimating the Economic of Festivals and Events: A Research Guide; CRC for Sustainable Tourism: Gold Coast, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Diedering, M.; Oklevik, O. Profile, patterns of spending and economic impact of event visitors: Evidence from Warnemünder Woche in Germany. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H. COVID-19: An opportunity to review existing grounded theories in event studies. J. Conv. Event. Tour. 2021, 22, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Analyzing the role of festivals and events in regional development. Event. Manag. 2008, 11, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Chen, J.S. Festival visitor motivation from the organizers’ points of view. Event. Manag. 2002, 7, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Smith, A. Events and sustainability: Why making events more sustainable is not enough. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1739–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredline, L.; Jago, L.; Deery, M. Host Community Perceptions of the Impacts of Events: A Comparison of Different Event Themes in Urban and Regional Communities; CRC for Sustainable Tourism: Gold Coast, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K.; Mjelde, J.W.; Kwon, Y.J. Estimating the economic impact of a mega-event on host and neighbouring regions. Leis. Stud. 2015, 36, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaręba, D. Ecotourism; Scientific Publishers PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, M. Indicators of sustainable tourism development. Man. Environ. 2011, 35, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hozer, J. Statistics Statistical Description; Department of Econometrics and Statistics at the University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 1998; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, R. Statistics; eMPi2: Poznan, Poland, 2000; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

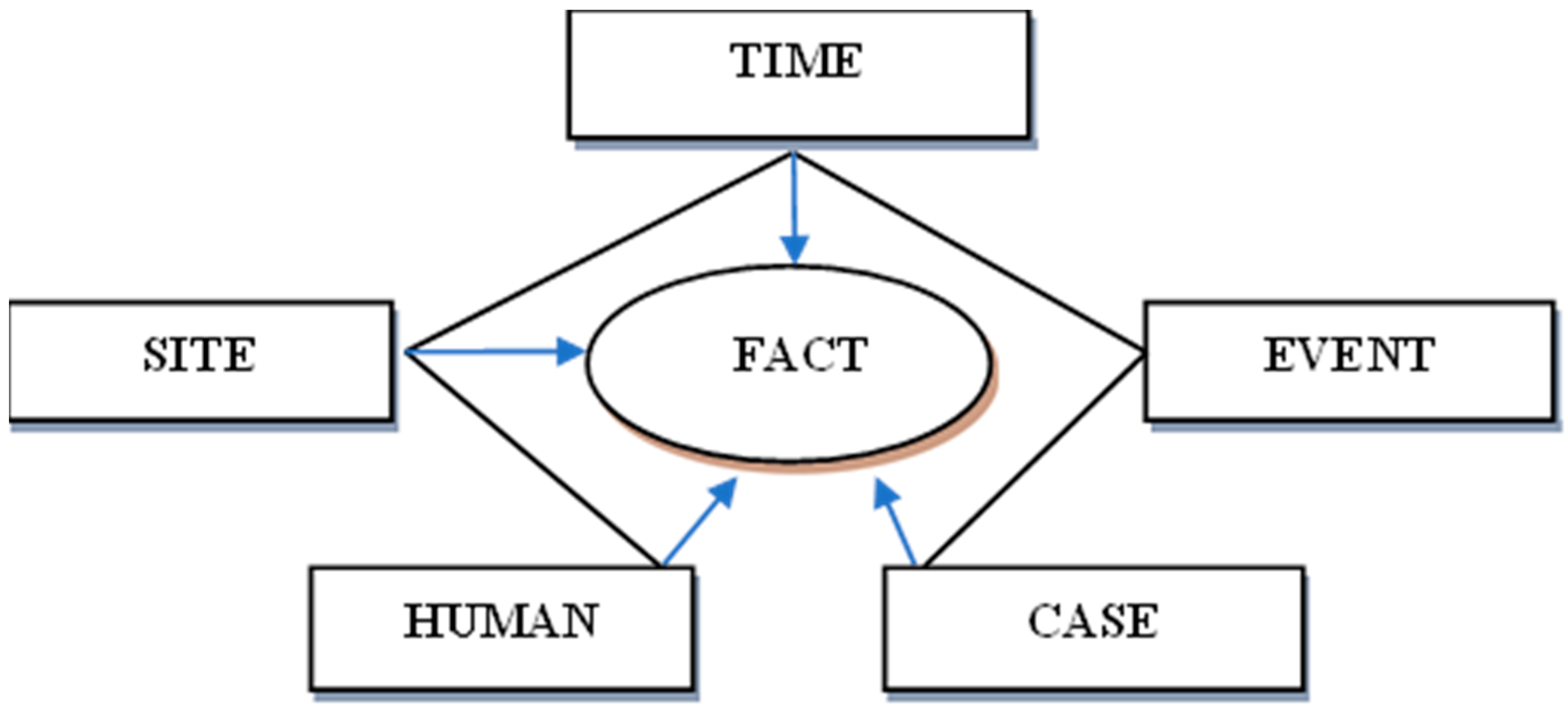

- Hozer, J. Time and Space in Econometric Modeling: Tempus, Locus, Homo, Casus et Fortuna Regit Factum; Publishing House of the University of Economic in Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 1998; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Namysłowska-Wilczyńska, B. Geostatistics: Theory and Applications; Publishing House of the Wroclaw University of Technology: Wroclaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cellmer, R. The Possibilities and Limitations of Geostatistical Methods in Real Estate Market Analyses. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2014, 22, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, R. Smooth interpolation of scattered data by local thin plate splines. Comput. Math. Appl. 1982, 8, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikechukwu, M.; Ebinne, E.; Idorenyin, U.; Raphael, N. Accuracy Assessment and Comparative Analysis of IDW, Spline and Kriging in Spatial Interpolation of Landform (Topography): An Experimental Study. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2017, 9, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, J. Geostatistical Methods for Natural and Technical Directions; Publishing House of the Warsaw University of Technology: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grzelakowski, A. Development of TEN-T corridors and their impact on the Polish transport and logistics system. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Gdańskiego. Ekon. Transp. Logistyka 2016, 59, 99–108. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171520219 (accessed on 15 September 2022). (In Polish).

- Rychter, M.; Szokało, A.A. Transport corridors running through Poland in the light of road transport infrastructure development. Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2017, 18, 1588–1591. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-162c4d57-51d6-484a-9680-9e02c905734e (accessed on 15 September 2022). (In Polish).

- Porta, S.; Latora, V.; Strano, E.; Cardillo, A.; Scellato, S.; Iacoviello, V.; Messora, R. Street centrality vs commerce and servive locations in cities: A Kernel Density Correlation case study in Bologna. Urban Plan. B 2009, 36, 450–465. [Google Scholar]

- Longley, P.; Goodchild, M.; Maguire, D.; Rhind, D. Geographic Information Systems and Science; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczycki, M.; Ligas, M. Interpolation of Geospatial Data Derived from Property Market. 2009, Volume 17. Available online: http://tnn.org.pl/tnn/publik/17/XVII_2.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Gibin, M.; Longley, P.; Atkinson, P. Kernel density estimation and percent volume contours in general practice catchment area analysis in urban Areas. In Proceedings of the Geographical Information Science Research UK Conference, Glasgow, UK, 11–13 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lijewski, T. Polish Transport Geography; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gierszewski, S. The Vistula in the History of Poland; ed. Sea: Gdańsk, Poland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pancewicz, A. River in the City Landscape; Silesian University of Technology: Gliwice, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Charzyński, P.; Gonia, A.; Podgórski, Z.; Kruger, A. Determinants of culinary tourism development in Pomeranian seller. J. Educ. Health Sport 2017, 7, 665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Orłowski, D.; Woźniczko, M. Culinary tourism in Poland—Preliminary research on the phenomenon of the phenomenon. Cult. Tour. 2016, 5, 60–100. [Google Scholar]

- von Rohrscheidt, A.M. Cultural Tourism: Phenomenon, Potential, Perspectives; Gniezno University of Humanities and Management, Millennium: Gniezno, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. We are what we eat: Food, tourism and globalization. Tour. Cult. Comun. 2000, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov, E. The Canadian Culinary Tourists: How Well Do We Know Them? University of Waterloo: Waterloo, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E. Culinary Tourism: A Tasty Economic Proposition; International Culinary Tourism Association: Portland, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Iwan, B. Cultural determinants of the Świętokrzyskie regional cuisine. In Cultural Determinants of Nutrition in Tourism; Makała, H., Ed.; University of Tourism and Foreign Languages in Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wysokińska, B. Historical elements in the creation and development of Mazovia’s culinary trails. In Culinary Trails as An Element of the Tourist Attractiveness of the Mazovia Region; Marshal’s Office of the Mazowieckie Voivodeship in Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowska, K. Cultural Tourism: Methodological Guide; Academy of Physical Education them. E. Piasecki: Poznań, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, P. Friedrich Ratzl’s anthropogeographical and geopolitical views. Geogr. Rev. 2015, 87, 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski, S. Historical conditions for the development of the Baltic-Adriatic transport corridor in Poland. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Geogr. Socio-Oeconomica 2014, 17, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Komornicki, T.; Śleszyński, P. Demand conditions of the Via Baltica route in Poland. Przegląd Komun. 2007, 2, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P.; Barański, J.; Degórski, M.; Komornicki, T.; Więckowski, M. The state of advancement of spatial planning in communes. Geogr. Work. 2007, 211, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Monitor; No. 26; Item 432; p. 563. 2001. Available online: https://www.money.pl/podatki/akty_prawne/monitor_polski/obwieszczenie;prezesa;rady;ministrow;z,monitor,polski,2001,026,432.html (accessed on 12 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kloskowski, D.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Janiszewska, D.; Ossowska, L. The Role of Metropolitan Areas in the Spatial Differentiation of Food Festivals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310689

Kloskowski D, Kwiatkowski G, Janiszewska D, Ossowska L. The Role of Metropolitan Areas in the Spatial Differentiation of Food Festivals. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310689

Chicago/Turabian StyleKloskowski, Dariusz, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski, Dorota Janiszewska, and Luiza Ossowska. 2023. "The Role of Metropolitan Areas in the Spatial Differentiation of Food Festivals" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310689

APA StyleKloskowski, D., Kwiatkowski, G., Janiszewska, D., & Ossowska, L. (2023). The Role of Metropolitan Areas in the Spatial Differentiation of Food Festivals. Sustainability, 15(13), 10689. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310689