Abstract

Driven by manufacturing supply reform and regional industrial transformation and upgrading, village industrial parks are key areas for deepening urban renewal. The complex relationship between various property rights actors is a key factor limiting the sustainable development of village industrial parks, and thus attracts considerable research. However, existing research is limited to individual cases and lacks systematic approaches to provide effective guidance for the renovation of village industrial parks. In addition, the paper summarises the participation pathways and characteristics of 12 typical cases of village industrial parks in the PRD. This is particularly true for rural industrial parks. The study identifies five scenarios based on the renewal of village collective ownership (government warehousing, land lease to developers, land lease to operating companies, land lease to enterprises, independent management); five situations based on the renewal of market enterprises’ rights of use (regular leasing, government support, abolition on expiry, introduction of enterprises, autonomous management); and four situations based on the renewal of government management rights (land expropriation, unified lease management, policy stimulation, supervision and management). The results are valuable for the research of urban regeneration and sustainable development in the context of government ownership.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of global urbanization, cities have entered an era of urban regeneration following the era of incremental expansion, and the main dilemma facing cities is the contradiction between the requirements of sustainable ecological, social and economic development and the unbalanced and inadequate urban carrying space. After more than 40 years of reform and opening up, the urban development mode has also shifted from extensive and extensional to intensive and connotative development. Meanwhile, the village collective industrial land has such problems as fragmented distribution, inefficient land use, low-end industry and serious environmental pollution [1], which is a typical representative of unbalanced and inadequate urban spatial development and poses a major challenge to the sustainable development of Chinese cities. Therefore, the village-industrial park transformation has become an important issue in the sustainable development of Chinese cities [2].

Village-level industrial parks are industrial parks built for productive purposes, such as industry, warehousing and logistics, on collective-owned village land in the context of China’s unique national land ownership structure. Village-level industrial parks were formed at the end of 1980s and the beginning of 1990s, against the background of the influx of labor-intensive industries in the early stage of reform and opening up, such as “three-plus-one” (processing, assembling of provided parts, processing given materials and compensation trade). Village-level industrial park land is collective construction land, which is bound up with the sustainable development of rural areas and is also an important component of the integrated development of urban and rural areas [3]. Moreover, village-level industrial parks make a significant contribution to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goals, especially Goal 13, which aims to develop ecological sustainability and protect the climate environment, and Goal 9, which aims to promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation [4].

However, the formation of village-level industrial parks has shown greater spontaneity, and their property right actors and property rights relations are relatively ambiguous and complex compared with state-owned land [5,6], its property rights structure and power conflicts may undermine social equity, economic resilience and surrounding ecological environment, and its different development modes profoundly affect urban sustainable development. To achieve the goal of inclusive and sustainable industrial development by promoting environmental protection, fostering innovation and competitiveness, creating jobs and diversifying the economy, governments across China must implement well-designed industrialization models and industrial policies. In 2007, as a national pilot city, Foshan put forward the principle of diversified investment, and encouraged the original property owners to develop jointly or separately with powerful investment developers, which allowed for the bottom-up exploration of village-level industrial parks’ renovation and putting forward the “six models” of village-level industrial parks (Government direct collection type; government account collection and storage type; government unified lease and management type; enterprise long-term lease self-management type; enterprise independent transformation type; government ecological restoration type). Since then, various prefecture-level cities in the Pearl River Delta have extensively discussed the mode of village-level industrial park renovation; for example, Dongguan proposed the “eight major transformation models” (Government storage and transformation model; municipal state-owned enterprise land improvement and development model; industrial enterprise self-transformation model; development enterprise acquisition and transformation model; village collective self-transformation model; village collective + industrial operator transformation model; collective land circulation transformation model; single entity listing investment transformation model), and Guangzhou proposed “five new models” (Government collection and storage model; state-owned enterprise leading model; leading enterprise leading model; operating institution leading model; village collective independent transformation model).

Existing studies have examined the property rights actors of village-level industrial parks in economically developed regions, such as the Pearl River Delta region, the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, and the Yangtze River Delta, from the perspectives of the government, markets, and villages [7,8,9]. Research in the Pearl River Delta region has found that excessive government supervision limits the distribution of benefits among participants, weakens the production intensity of village-level industrial parks, leads to a lack of market attractiveness of projects, and limits the positivity of the market [10,11,12]. The dominance of the market and the reconfiguration of the land tenure structure will also affect changes in the state land system and limit the state’s management of land [13,14]. In addition, government expropriation of collective land will lead to urban sprawl and generate social conflicts, for example by limiting villagers’ income from land transfer and increasing the inability of residents who have lost their land to resettle [15,16,17]. Studies in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region show that in the process of stakeholder participation in collective construction land, the unclear definition of construction land property rights leads to the establishment of incomplete collective rights of occupation, use, income and disposal, and the government has thus established implicit occupation rights over collective construction land [18]. Studies in the Yangtze River Delta region point out that the public, as the most fundamental stakeholder in industrial land redevelopment, is excluded from decision-making, which tends to neglect public interests [19,20,21]. In general, studies in the Pearl River Delta region emphasize private power, those in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region emphasize government power, and those in the Yangtze River Delta region emphasize market power [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. At present, the research and institutional development of property rights actors in village-level industrial parks is still in its initial stage, and the analysis of property rights actors in village-level industrial parks mainly focuses on individual case studies, lacking systematic horizontal comparisons and summaries of different models. At the same time, China’s village-level industrial parks involve complex property right actors; the current research shows that the cooperation mode has a certain influence on society, ecology, economy and politics, but there is a lack of in-depth analysis and attempts to develop theoretical frameworks on the operational mechanisms of multiple benefit play. Therefore, under the specific institutional environment of China, it is of great significance to study the sustainable development path of village-level industrial parks in order to construct the relevant theoretical model and analytical framework of cooperation among power subjects based on the influence of resources, rules and organisational concepts involved by different right subjects.

Using the ‘structure-participant’ model as an extension framework, the paper explores the environmental, economic and social culture of sustainable village industries and discusses a healthy and sustainable way of developing village industries. It also examines how these different pathways contribute to environmental, economic, social and cultural sustainability, so as to explore the applicable situation and internal logic of different transformation paths.

2. Research Area and Analytical Framework

2.1. Study Areas and Data

The Pearl River Delta contains a large quantity of village collective construction land, accounting for more than 50% of the total construction land area in the region, where there are 3853 village-level industrial parks covering an area of about 976 square kilometers. At the same time, due to the limited land resource reserves, the mismatch between land supply and demand, and the large degree of land fragmentation, the Pearl River Delta has become a pioneer area of exploration for the redevelopment of inefficient construction land in villages and towns in China. In the process of exploring village-level transformation in metropolitan cities such as Guangzhou, Foshan and Dongguan, village-level industrial parks in inefficient construction land have complex authority subjects and low interest drive, which makes the transformation of village-level industrial parks become one of the main difficulties in the sustainable development of collective construction land in the Pearl River Delta region. Therefore, the Pearl River Delta region is a typical industrial agglomeration region in the world, which is of great significance to the research on the participation mechanism of power subjects and the investigation of sustainable development.

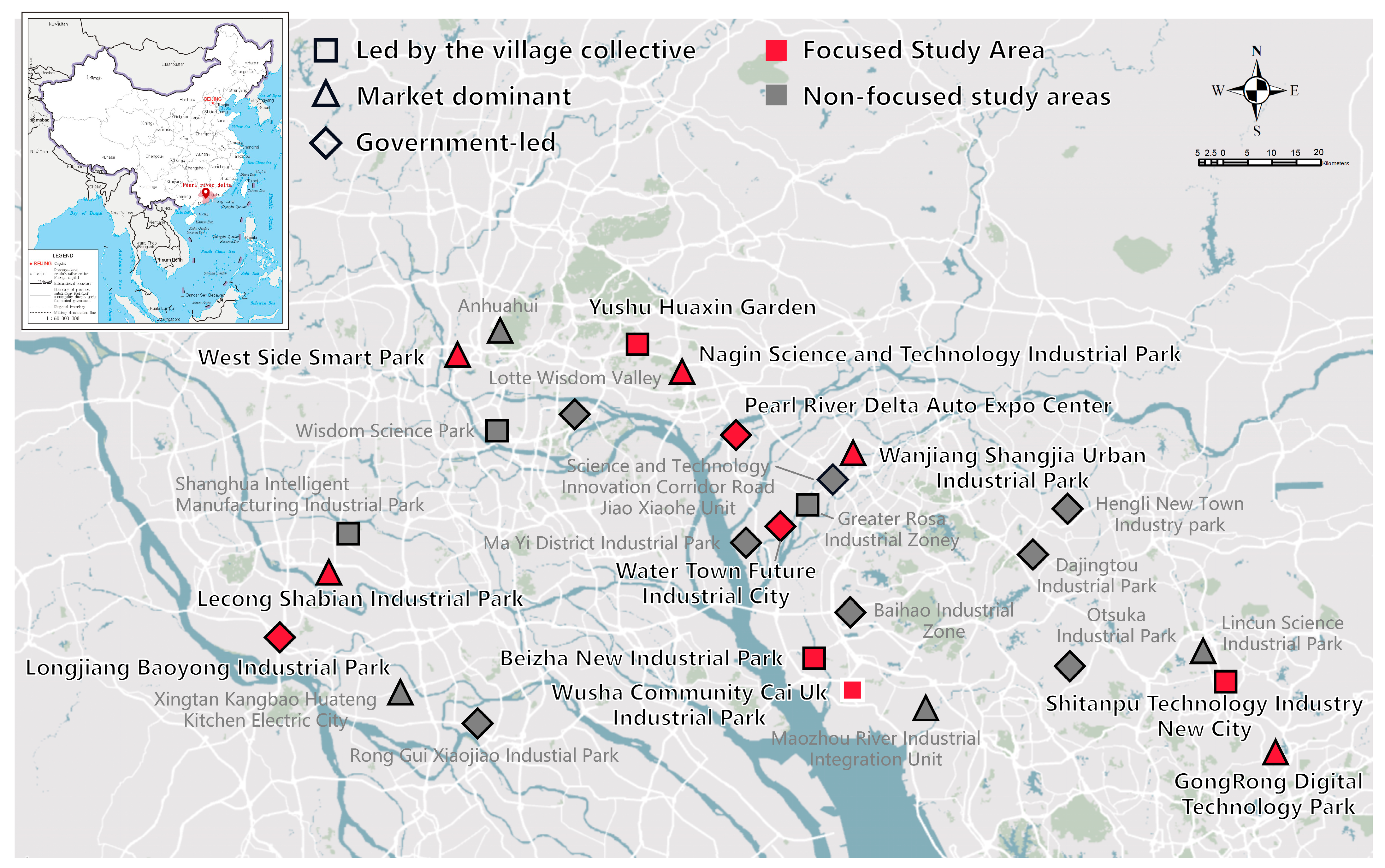

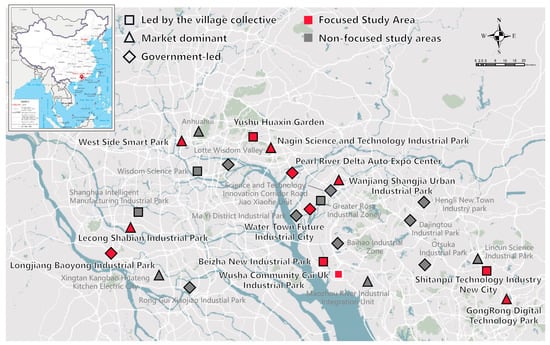

From October 2020 to May 2022, 27 cases of village-level industrial parks were investigated. All of them were within the three old renovation pilot cities: 6 were in Guangzhou, 16 in Dongguan and 5 in Foshan. Through the analysis of the renovation paths of different property right entities, 12 typical cases, including Xicheng Zhihui Park, were screened, representing the renovation paths of village-level industrial parks led by distinct property right entities (Figure 1). The study conducted 48 on-site inspections of the 12 cases, focusing on the ecological environment, spatial effects, supporting facilities, greening systems and cultural elements of the village after their transformation. The interviews incorporated 270 people representing operators, government workers, village committee staff, villagers, enterprise employees and other relevant groups, and focused on transformation subjects, transformation content, industrial structure, business conditions, property rights composition, consultation processes and cooperation mechanisms between market entities and village collectives, governmental planning, public participation, etc.

Figure 1.

Case distribution map of village-level industrial parks.

2.2. Analysis Framework

The “structure–participant” model is a classic model proposed in the 1990s by Professor Healy of Newcastle University in the United Kingdom for analyzing the control of real estate development. It can be utilized to analyze the processes of different participants involved in land, buildings and urban construction, so as to explore the external relationship between internal interests and society and the economy in the process. This model is applicable to case studies of unstable race conditions in different contexts [29]. Village-level industrial parks are endowed with the distinctive feature of chaotic land tenure relations [30], and different property rights entities own different production elements, resulting in unstable competition, so the “structure–participant” model is thus applied. Here, “participants” refers to landowners, developers, consultants, government planners, etc.; “structure” refers to the resources owned by participants (production factors such as land, capital, labor and management capacity owned by each participant), rules (institutional and political groups, including laws, regulations, customs, etc., that shape and constrain participants’ behavior) and organizational concepts (participants’ interests affect the use of resources and the formation of rules) [31]. The “structure-participant” institutional model is mostly applied in single case analysis, but in order to summarize the general pattern and analyze multiple cases more systematically, this paper improves the steps of the traditional “structure-participant” model. First, we take different power actors as the base point and systematically deduce their transformation paths in different situations; then, we investigate the process of land redevelopment and interview the participants to objectively describe the effects of the case before and after transformation; third, we analyze the roles and impacts of different participants in the process of land redevelopment. Finally, the case study is combined with social theory to reveal the main factors affecting the process and sustainability of industrial land transformation under the existing land power system and the possible outcomes of the participation of power actors in the process, thus providing a theoretical and empirical basis for objectively evaluating the existing research on industrial land redevelopment models and development paths.

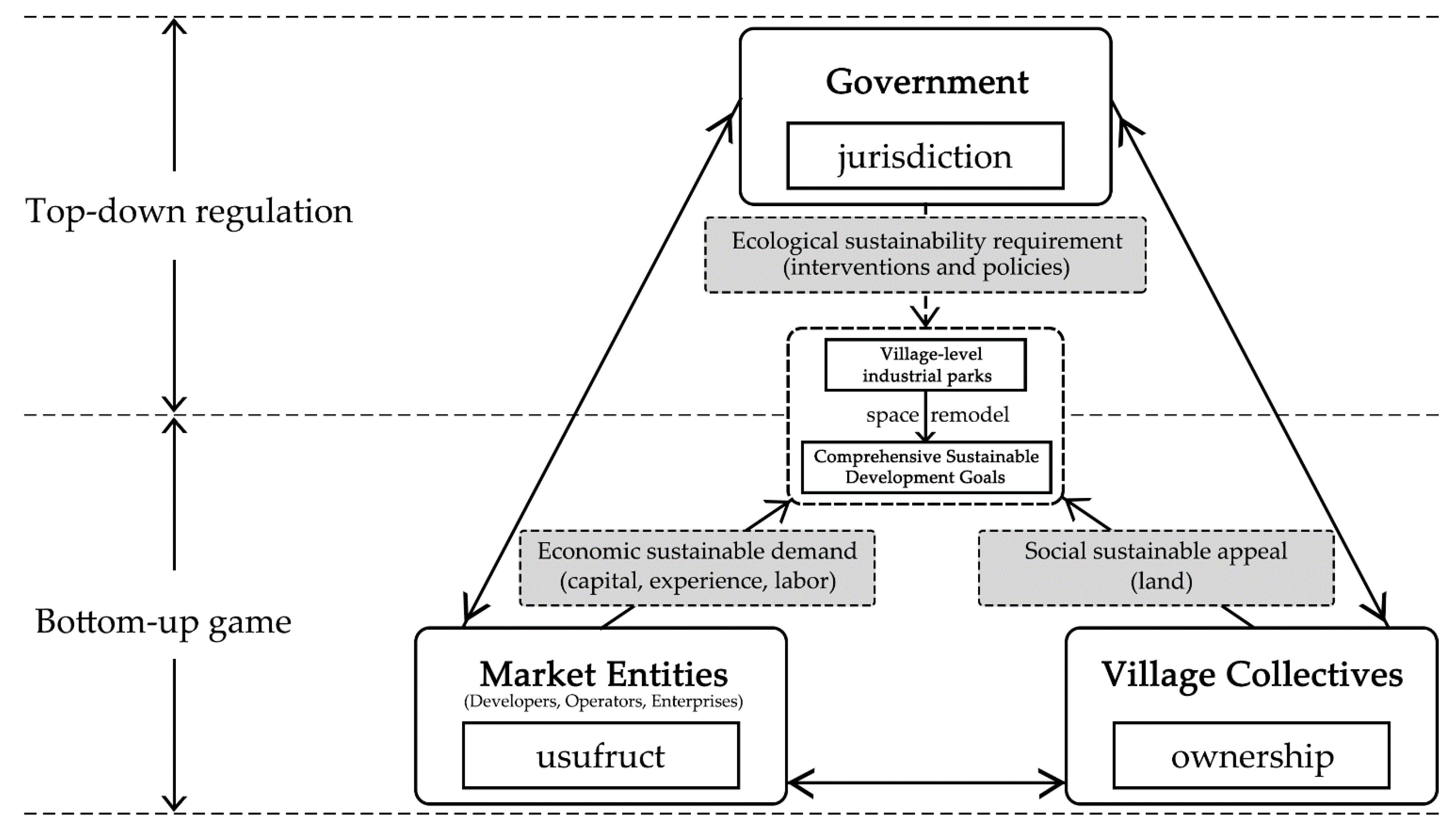

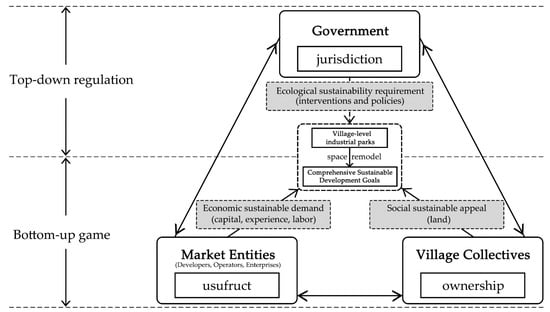

In order to explain the relationship of interests and the logic of path deduction among the power subjects more clearly, this paper composes the general framework of resources, power and organizational concept possessed by the main subjects involved in the transformation of village industrial parks. The main property rights entities involved in the transformation of village-level industrial parks include village collectives (property rights entities) [32], markets (implementing entities) [33] and governments (management entities) [34], among which village collectives have ownership of the land of village-level industrial parks, the government has jurisdiction, and market entities have usufruct right. In terms of organizational philosophy (i.e., development goals), (1) the village collective concentrates on collective interests and social sustainable development goals, (2) market entities focus on sustainable economic development goals, and (3) the government cares about public governance and ecological sustainable development goals [35]. The structural elements required for transformation include resources and rules; resources are production factors such as land, capital, operation and management experience and labor [36], and the rational allocation of production factors determines the level of industrial development [37]. The rules are government intervention and affirmative policies. the structural elements held by different property rights entities are disparate: (1) the resource elements held by the village collective are land (L); (2) the resource elements possessed by market entities are funds (FD, specifically developers), operation and management experience (E, specifically operators) and labor (LP, specifically production enterprises); (3) the rules at the government’s disposal include its interventionist behaviors and supportive policies (P). Since the elements related to village collectives and market entities are resource elements and direct participation in transformation, this is a bottom-up game process. The elements wielded by the government are rule elements, and their interventionist behaviors and policy elements are regulatory elements of the model, which are not directly involved in the transformation, so they belong to the top-down part of the adjustment process. In the transformation of village-level industrial parks, different transformation and evolutionary paths may be adopted due to the distinct development goals and mastery factors of diverse power subjects (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of “structure–participant” model of village-level industrial park.

3. Transformation Path Based on Ownership of Village Collectives

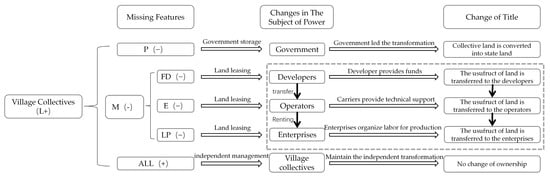

3.1. Deduction of Transformation Path Based on Village Collective Ownership

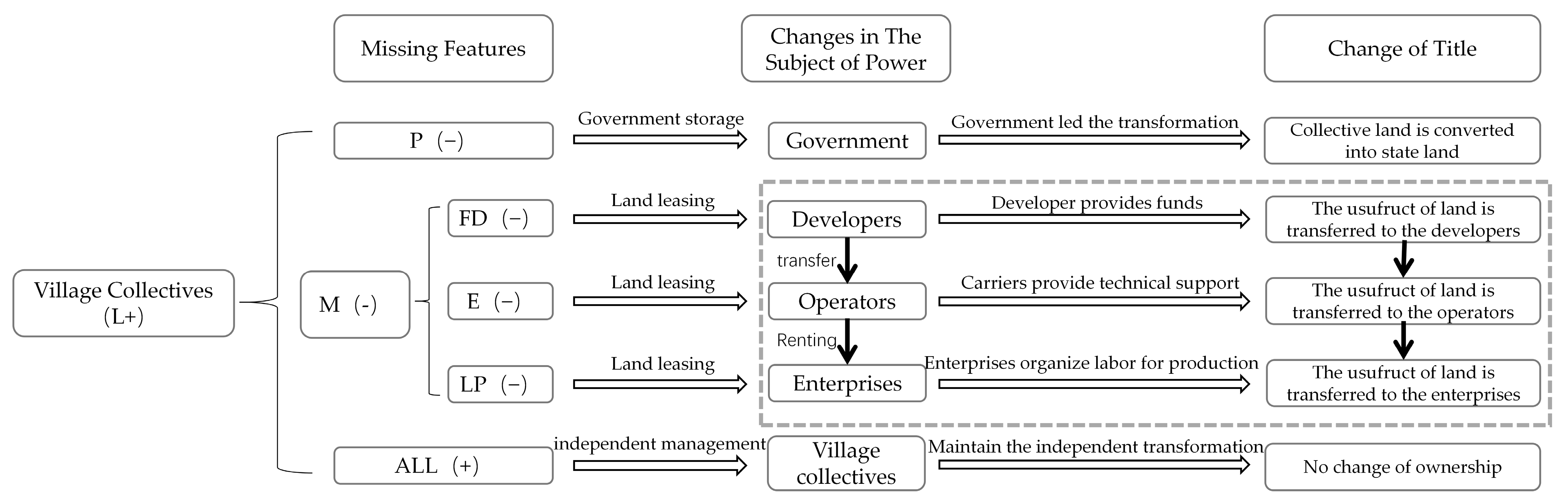

The village collective is the owner of the construction land in village-level industrial parks, and the production factors it controls are land, while other production factors, such as capital, operation and management experience, and labor, are not unique to it. The rule elements include the uncertainty of interventionist behavior and policy regulation. The presence or absence of different elements determines the evolution of five village-level industrial park transformation paths (Figure 3). When the transformation lacks the support of policy elements, the land of the village-level industrial park may be collected and stored by the government and thus coordinated, and the collective land will be taken under state ownership, according to which the nature of land ownership of the village-level industrial park will change. If the transformation lacks production factors, market forces need to intervene to assist the village collective, and three situations may thus occur: when there is a lack of funds, the village collective needs to lease the land to the developer, and the developer will provide funds to develop the land, at which time the collective land usufruct is transferred to the developer; when there is a lack of management capacity, the village collective needs to lease the land to the operator, and the operator will assist in the management of the village-level industrial park, at which time the collective land usufruct will be transferred to the operator; when there is a lack of labor, the village collective needs to lease the land to the enterprise, and the enterprise organizes manpower to carry out production activities, at which time the collective land use right is transferred to the enterprise. In the above three situations, the change of power is reflected in the transformation of the usufruct subject; when the village collective wields high economic strength and does not need special policy incentives from the government, the village-level industrial park is operated and transformed by the village collective independently without the shift of power subjects.

Figure 3.

Village collective decomposition mechanism path map. Note: ALL represents all elements, (−) indicates lack of elements, (+) indicates presence of elements, and M refers to the market.

3.2. An Empirical Analysis Based on the Transformation Path of Village Collective Ownership

3.2.1. Government Storage Path

The government storage path mainly arises in situations where the lack of policy support in the park gives rise to the inability of the village agglomeration to promote the transformation, under which conditions the village collective can obtain short-term capital compensation and tax sharing arrangements suitable for projects with simple tenure relationships and easy land consolidation in line with the government’s collection and storage plan. Among the cases that follow this path are the Pearl River Delta Auto Expo Center, the Science and Technology Innovation Corridor Xiaohe Area, and Wisdom Valley in Xinhong Bay District. Among these, the Pearl River Delta Auto Expo Center is the most typical. Before the renovation of the Pearl River Delta Auto Expo Center, it was mainly a warehousing and logistics industry, with typical problems such as little greenery, a poor ecological environment, a lack of public facilities and old factory buildings. After the Mayong Town Joint Stock Economic Union converted 14.4 hectares of collective construction land into state-owned construction land, the Mayong Town Government collected and stored it, and then launched a public sale on the market. After the renovation, the annual output of the industrial park is expected to increased from CNY 10 million to CNY 5 billion, with tax revenue being increased from CNY 1 million to CNY 300 million. Under this scheme, a village collective can receive a one-time compensation fee of CNY 5 million for land acquisition, CNY 47 million for the share of revenue of the land transfer, and CNY 209 million for the balanced index fee (The undisclosed data are from “Operation Guide of Eight Modes of Industrial land redevelopment in Dongguan City” and “Introduction to Industrial Park Transformation in Towns and Villages of Dongguan City”. Data are available with the permission of Dongguan Bureau of Natural Resource).

On this path, the large short-term economic benefits gained by the village collective include the transfer of land ownership, and the transformation is mainly led by the government. The survey results show that the Pearl River Delta Auto Expo Center has achieved higher output, a better ecological environment and better infrastructure since renovation and conducive to ecological and economic sustainability. But the government’s intervention and capital accumulation have suppressed the bottom-up communication of villagers’ substantive demands related to the transformation, resulting in inconsistency between the supply and demand of public facilities, with detriments to the local traditions, culture and regional characteristics of village-level industrial parks, driving the loss of rural culture and spirit, not conducive to social sustainable development [38].

3.2.2. Land Leasing Path

The land leasing path mainly occurs when the park lacks market factors such as capital, management ability and labor, which make it difficult to promote transformation. Typical cases from the survey include the Beizha New Industrial Park, Yushu Huaxin Park and the Shitanpu Community Industry New City. In the context of low economic benefits before the transformation, a large number of unemployed people and insufficient supporting facilities, the market has provided effective solutions. Since the renovation, the Beizha New Industrial Park in Humen Town has provided 24,000 jobs for villagers; the monthly standard rent of the village collective was CNY 28 per square meter, and the annual rent increased from CNY 15 million to 104.68 million. Guangzhou Yushu Huaxin Park has added new infrastructure or repaired existing supporting facilities in its village-level industrial parks, such as adding gyms, outdoor sports fields and electric vehicle charging piles, and repaired fire protection systems, with the rent of factory buildings increasing from the original CNY 30/square meter to 50/square meter per month. Shitanpu Community Science and Technology Industry New City and the village collective jointly funded the construction of public facilities, such as surrounding road networks, primary schools and sports parks, providing 90,000 jobs, and the village collective received CNY 160 million in cash compensation and 228,700 square meters of factory properties. The annual rent also increased from CNY 34 million to 78 million.

This path involves the retention of collective land ownership, and the benefits of transformation are mainly felt by the village collective and the market, with a high degree of acceptance on the part of the village collective. The survey results show that market players pay more attention to the economic benefits and business environment after the transformation of industrial parks, thus improving the supporting facilities surrounding collective construction land and the production efficiency, as well as providing jobs, which is mainly conducive to social sustainability. However, due to the ambiguity of collective land property rights, the land lease economy, welfare collective economic organization and other problems [39,40,41], land leasing may lead not be the most effective means of development for collective land, and the sustainable economic development may be hindered to some extent.

3.2.3. Independent Management Path

The independent management path mainly develops when the village collective owns all the production factors and has obtained policy support, and is thus suitable for parks where the village collective possesses strong economic influence and traditional industries need to be retained. The cases following this path include the Yinchung Yinzhou Paper Mill Project and Caiwu Village-level Industrial Park, of which the Caiwu Village-level Industrial Park is the most typical. Before the regeneration, the park was mainly dominated by molding, garment and leather production and other processing plants. The buildings were aging, and the processing industry created much pollution in the surrounding areas. The park was given CNY 410 million in investment by a wholly owned subsidiary of Wusha Caiwu Joint Stock Economic Cooperative in Chang’an Town, intended to transform the original factory properties; under this system, the land and factories are collectively owned. Since the regeneration, the annual rental income of the village collective has increased from CNY 8.6 million to 42 million, the exterior walls of the park buildings have been renovated, the public facilities have been improved, and a large number of the original traditional industries have been retained.

When on this path, the village collective has the highest degree of ownership, and the transformation is led by the village collective. The survey results show that the village collective hopes to protect the culture and spirit of the village while carrying out the development of the original village enterprises, preserving a large number of traditional industries in the village-level industrial park and the spatial rights of regional cultures and indigenous people to the greatest extent, social equity, labor rights and social culture are protected, and sustainable social development is guaranteed. However, compared with market-led transformation, the output value and tax contribution of traditional industries are low, and the environmental pollution caused by traditional industries remains a problem, which is not conducive to sustainable economic and ecological development.

3.3. Comparison of Transformation Paths Based on Village Collective Owners

In the process of participating in the transformation of village-level industrial parks, the lack of different structural ownership elements leads to the emergence of one of three paths: government storage, land lease, and independent management. Since the interests of owners and benefits to be derived in the process of reusing construction land mainly include obtaining rental income, upgrading social facilities and preserving village culture. Therefore, the study believes that the way village collectives participate in the transformation of village industrial parks with land elements will mainly affect the social sustainability of village industrial parks. In the path of government storage, the change of ownership subject directly weakens the voice of village collectives in the transformation, and the social sustainability of industrial parks will be greatly weakened; in the path of land leasing, because the transfer of use rights divides the voice of village collectives in the transformation, the social sustainability of industrial parks will be unstable in the game of multiple parties; in the path of independent management, because the ownership subject does not change, village collectives hold the absolute voice, and the social sustainability of industrial parks will be significantly improved after the transformation (Table 1). However, Compared with market entities and government entities, due to the lack of consideration of public services and market factors in villagers’ decision-making process, when the village collective leads the transformation of industrial parks, problems such as low output value and tax contributions, and insufficient public facilities, may arise, and the ecological and economic sustainability may be limited after the renovation.

Table 1.

Basic situations of village collective participation path research cases.

4. Transformation Path Based on Usufruct Rights of Market Entities

4.1. Deduction of Transformation Path Based on Usufruct Rights of Market Entities

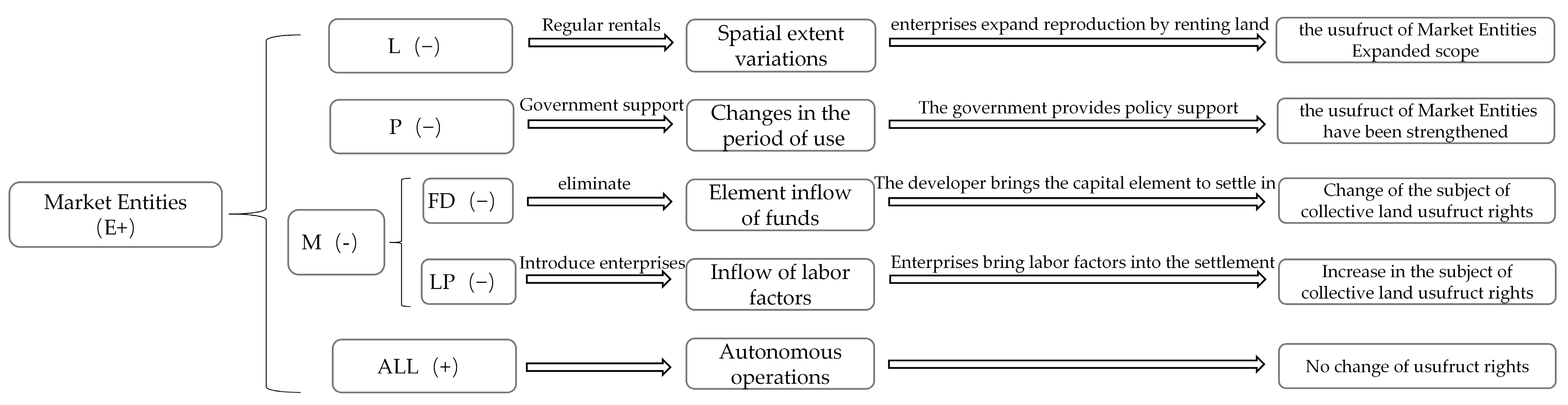

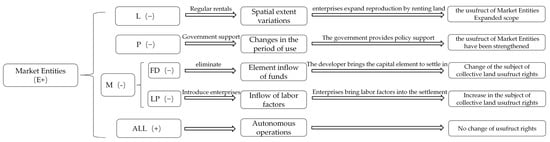

The market entities at play in village-level industrial parks include developers, operators and enterprises, and developers are mainly responsible for the investment in and development of the park in the initial stage of construction. The operator is responsible for long-term development, operation and leasing profitability during the construction of the park. The enterprise is mainly responsible for the introduction of production materials and labor in the later stage of park construction. Among them, the operator is the main implementer in the process of village-level industrial park transformation, and they undertake management and coordination during the construction of the park. Market entities represented by operators tend to be endowed with management skills, while other production factors such as capital, labor and land control are not unique to this approach. Rule elements such as intervention behavior and policy regulation are also uncertain here, and five development paths are likely to evolve (Figure 4). When the land market entity is missing, it is necessary to lease land to the village collective, at which point the spatial scales of the production activities of the market entity change, and the scope of land held by the market entity is expanded. When the policy market entities are missing, the government needs to provide policy support, at which point market entities may receive more complete and strengthened usage rights, with land use rights enhanced. When the market entity lacks funds, a new developer may need to take control, and the subjects of the collective land use rights will change. When the labor force of market entities is missing, it is necessary to introduce more enterprises, and collective land usage rights increase. When market entities have all the production factors and do not need special policy incentives from the government, they may choose to operate independently, and there will be no change in the property rights in village-level industrial parks.

Figure 4.

Market entities’ decomposition path map. Note: ALL represents all elements, (−) indicates lack of elements, (+) indicates presence of elements, and M refers to the market.

4.2. An Empirical Analysis Based on the Transformation Path of Market Entities’ Usufruct Rights

4.2.1. Regular Rental Path

The regular rental path mainly arises when the market entity expands the reproduction process but is constrained by land factors, making it suitable for projects wherein the production space of the village-level industrial park is insufficient and the market entity has sufficient funds to expand it. The cases that follow this path include Xicheng Zhihui Park, Gongrong Digital Science and Technology Park and Lecong Shanghua Industrial Park, among which Xicheng Zhihui Park is the most representative. Before the transformation, Xicheng Zhihui Park contained mainly logistics and warehousing properties, with high building density and singular space functions. In order to reduce building density and obtain a better business environment, the operators obtained abundant land elements through conventional leasing, and after renovation, built new multi-functional living spaces such as shared fitness facilities, internet celebrity photography spaces, green spaces and business exhibition halls. At the same time, in order to obtain a higher floor area ratio and further increase the production space, operators transformed traditional industries into new industries to obtain subsides for floor area ratio.

In this path, the spatial scope of market entities’ right to use is expanded, and the transformation is jointly led by the user and the owner. The survey results show that more small enterprises will participate in the transformation process to capitalize on opportunities for industrial transformation and develop more diversified spatial functions. At the same time, ecological pollution is reduced and ecological sustainability is guaranteed. However, without government intervention, bottom-up transformation leads to smaller enterprises and greater mobility, while usage functions of mixed land and low land efficiency will easily emerge, economic market cannot guarantee sustainable operation, and the lack of sustainable economic development.

4.2.2. Government Support Path

The government support path mainly arises in situations wherein a lack of policy elements in the park leads to the inability of village collectives and enterprises to establish cooperation, and is thus suitable for projects with complex ownership and insufficient market interest, among which Huangpu Steel Trade Logistics Park is the most typical. Before the transformation, Huangpu Steel Trade Logistics Park was dominated by the steel trading and warehousing industries, which generated significant noise and smoke pollution via the transportation of goods. Its transformation faced two problems: first, the high cost of land consolidation in the early stage; second, the introduction and cultivation of industries after transformation takes a long time, and the short-term benefits are low, which ultimately leads to low willingness related to market capital investment and transformation. Therefore, the Land Acquisition Office of the Guangzhou Development District Government took the lead in signing a contract with the village collective, leasing the land owned by the village collective for a longer period, and the government, as the intermediate endorser, subleased the land to Najin Technology Co., Ltd., as well as providing policy funds to help it obtain investment. After the transformation, the enthusiasm of the market was hugely increased, and the industry entered high-end development, wherein information technology accounted for 60%, and biomedicine and intelligent manufacturing accounted for 20% and 10%, respectively, of the newly generated industry, and the occupancy rate reached 98%. The park has been transformed from steel warehouses to a high-tech industrial park, enhancing the quality of construction and the aesthetic of the park. The park now also employs a professional cleaning team responsible for maintaining the environment and reducing pollution and noise.

On this path, some market entities have obtained land operation rights for up to 47 years due to government intervention, while investment transformation and long-term operation guarantees have been enhanced, with the transformation being led by market entities. The survey results show that market entities obtain sufficient profit boosts after government support, the enthusiasm of operators and major small- and medium-sized enterprises has been greatly mobilized, and the long-term accumulated conflict between village and enterprise and the conflict of sustainable economic development has been resolved.

4.2.3. Eliminate upon Expiration Path

The eliminate upon expiration path mainly arises situations where market entities lack funds due to the gradual reduction in value-added income from the park; this path is suitable for projects with chaotic business structures and insufficient funds, among which Tongde Shoe Base is typical. Before the renovation, due to the lack of funds and poor management approaches of the old user right holders, more shops occupied the area, and the structure was chaotic. Since the contract between the old user right holder and the village collective was still within its period of validity, after the old market entity subleased the collective land, the Zhihui Group renovated the park as the new developer. After the transformation, most of the logistics enterprises in the Tongde Shoe Base were cleared away, after which the industry here was mainly based on technology research and development, with a variety of commercial functions coexisting. The buildings became more modern with more diversified space functions, with the building of a photography base, a net red street and a conference center, which could host road shows, press conferences, salons and other activities.

On this path, the transfer of the usufruct rights of the old market entity reduces the loss of operation, and the transformation is led by the new developer. The survey results show that the renovation funds invested by new developers will restore order to the chaotic business environment that held before the renovation, and the spatial functions will be made more diversified. However, the reconstruction of the park space by the new user rights holder will lead to the redevelopment of village-level industrial parks by foreign parties [42], which will affect the social sustainability in the park. At the same time, in this case, the emigration of original traditional industries and indigenous peoples has led to the replacement of the village’s original culture by an internet celebrity-based culture.

4.2.4. Introduce Enterprises Path

The path of introducing enterprises mainly develops when market entities lack labor factors, and the production capacity of the original small enterprises cannot fulfill the development needs, etc. It is thus suitable for industrial parks seeking to optimize their hardware facilities and production materials, and enhance their production capacity to obtain higher output value. Gongrong Digital Science and Technology Park is a representative case of this path. Before the renovation, Gong Rong Digital Technology Park mainly comprised an old processing plant, which had low production efficiency and insufficient jobs. After the Gongrong Digital Science and Technology Park introduced supporting enterprises, such as technical departments, finished product warehouses and processing production lines, the upgrading of production materials and the adjustment of the industrial structure were achieved. Since the renovation, Gongrong Digital Science and Technology Park has shown improved productivity, and the annual output value has increased from CNY 200 million to 2 billion, with the annual tax revenue expected to be CNY 85 million with the provision of about 4000 jobs. Since the settled enterprises belong to the M1 land category, they all receive financial subsidies from the government, and the operators have transferred 30,000 square meters of industrial plant to the village collective as compensation.

On this path, the usufructuary subleases the construction land to different enterprises, and the transformation results from negotiation between the operator and the small enterprise. The survey results show that, with the guidance of market players, the replacement of new and old enterprises, as well as of the production functions of village-level industrial park spaces, has been enhanced, and village-level industrial parks obtain higher floor area ratios and financial subsidies in response to government policies. At the same time, here, part of the industrial plant was transferred to the village collective, which ensured the long-term income of the latter party. However, the surrounding infrastructure and public services are still relatively sparse, and the social sustainability benefits are not apparent.

4.2.5. Autonomous Operations Path

The independent operation path mainly develops when the market entity has both production factors and policy factors, but the existing means of production cannot fulfil the production demand; this path is applicable to projects where the market entity does not want to deal with the risks and costs associated with cooperation, and has historically carried out perfect historical land use procedures. The cases that follow this path in the survey include Xingtan Kangbao Huateng Kitchen Electric City and Wanjiang Shangjia Urban Industrial Park, of which Wanjiang Shangjia Urban Industrial Park is typical. Before the transformation, the industrial park was dominated by office buildings, and the production capacity of the existing plant was weak. Wanjiang Shangjia Urban Industrial Park was independently transformed by Ruirong Industrial Investment Company with an investment of CNY 150 million, with the operator hoping to invest a small amount of money to obtain a high return, according to which large-scale demolition and construction are not in line with its interests. The Shangjia Urban Industrial Park underwent partial demolition. After the renovation, the park converted two office buildings into intelligent manufacturing plants, and it increased the plot ratio of the industrial park from 1.52 to 3.5 and the output value from CNY 150 million to CNY 600 million, providing about 1000 jobs.

On this path, the transformation is led by market entities. The survey results show that independent operators often choose to carry out partial demolition, functional changes, decoration and repairs. At the same time, the operators can improve land use and pursue construction procedures according to policy requirements, realizing the transformation and upgrading of land use via changes to building functions so as to obtain plot ratio and financial subsidies. The subject of the right to use under this model will not change, and the status quo of the construction pattern will be maintained; it thus only provides a small number of jobs and does not build new public facilities in the surrounding areas, and the benefits of social welfare and sustainable development are not obvious.

4.3. Comparison of Transformation Paths Based on the Usufruct Rights of Market Entities

In the process of transforming village-level industrial parks, the lack of different structural elements associated with the usufruct right holder may lead to one of five paths emerging: regular rental, government support, expiration elimination, introduction of enterprises and autonomous operation. In this case, the activities of the users mainly meet the production demand, thus increasing the production capacity of the park and yielding greater economic benefits. Therefore, the study concludes that the way the market carries capital, management talent and labor elements to participate in the transformation of village industrial parks will mainly affect the economic sustainability of village industrial parks. In the regular rental path, although the scope of tenure increases, the ownership is still held by the village collective, and the economic sustainability of the industrial park will have unstable changes in the game between them; in the government support path, because the government intervenes to solve the contradiction between the village collective and the market, the industrial park will be more stable and economically sustainable; in the eliminate upon expiration path, because the subject of tenure changes, the economic sustainability will be restored; in the introduce enterprises path, the economic sustainability of the industrial park will be enhanced due to the increase of the production capacity of the right holder; in the path of autonomous operation, the economic sustainability of the industrial park will be enhanced due to the increase of the spatial function of the industrial park (Table 2). Compared with village collectives and governments, because market entities want to reduce the risk and required capital investment, as well as utilizing the spatial surplus value of village-level industrial parks, the transformation of village-level industrial parks led by market entities may cause traditional industries and village-affiliated cultures to be replaced, as public resources will be unfairly distributed.

Table 2.

Basic situations of market entities’ participation paths in the research cases.

5. Transformation Path Based on Stewardship of Government

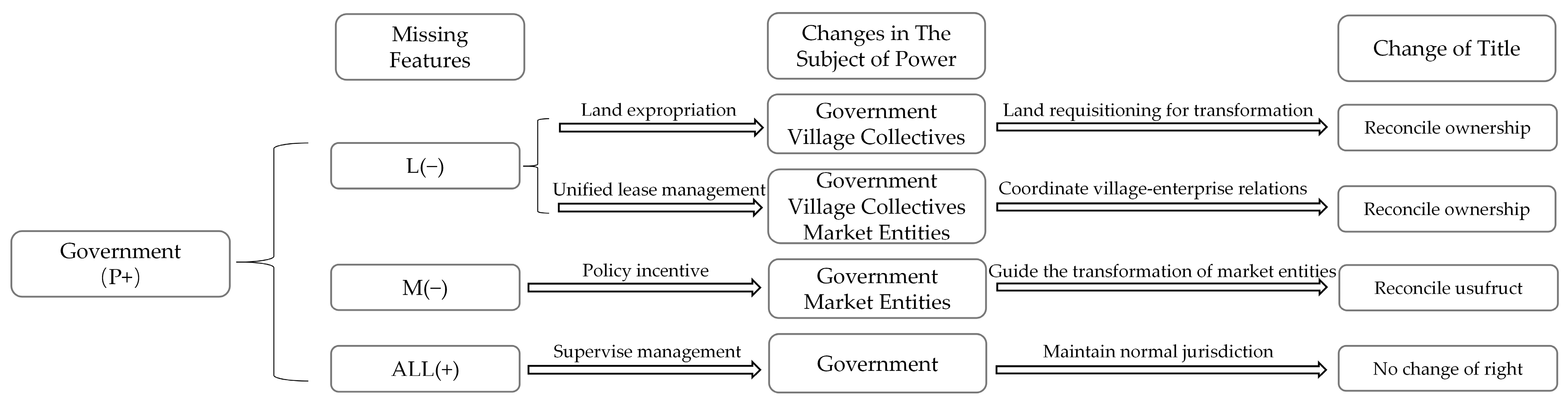

5.1. Deduction of Transformation Path Based on Stewardship of Government

From the perspective of the government, based on land jurisdiction, the rule elements will have an impact on the resource elements of capital, experience, labor force and land possessed by the village collective, and will eventually determine the ownership and use of land, which process may evolve along one of four development paths (Figure 5). When government land is missing, land expropriation or unified lease management may be chosen. If the government expropriates land, the collective land will be transferred to state ownership, and the government will thus regulate the ownership. If the government carries out unified lease management, the government regulates the relationship between enterprises and village collectives, according to which the transformation of village-level industrial parks can proceed smoothly, and the government will regulate the ownership of land. When the government lacks market elements, it may provide policy incentives for market entities to settle in village-level industrial parks, at which time the government regulates the right to land use. When the government owns all the factors of production, it only needs to implement supervision and management policies to maintain day-to-day jurisdiction, and there will be no change in the property rights of village-level industrial parks.

Figure 5.

Government decomposition mechanism path map. Note: ALL represents all elements, (−) indicates lack of elements, (+) indicates presence of elements, and M refers to the market.

5.2. An Empirical Analysis Based on the Transformation Path of Government’s Stewardship

5.2.1. Land Expropriation Path

The land acquisition route is mainly followed when local governments want to obtain long-term revenue through land finance. It is suitable for projects wherein the land resource, the most valuable asset under the control of local governments, is easier to organize in the early stage, and after land expropriation, the government generates income by leasing land use rights and collecting land use fees [43]. The cases that follow this path in the survey are Water Town Future Industrial City and Foshan South Entrance Emerging Industrial Park, among which Water Town Future Industrial City is typical. Before the transformation, the Water Town Future Industrial City project was part of the industrial park built in the early development stage of Hongmei Town, and faced problems such as low land use efficiency and a lack of public infrastructure. The total tax revenue of the area in 2019 was about CNY 46.63 million, with the average tax revenue per month as only CNY 17,000, which is far lower than the average level of Dongguan City. After centralized renovation, the government will enact a functional design based on the characteristics of the town, characterized by scattered green space, school and other public resources, and they plan to build two large parks, one cultural and art center and four high-standard schools, to create high-quality industrial supporting facilities and public spaces that adhere to the town’s characteristics (The undisclosed data are from “Brief introduction of Dongguan Water Town Future Industrial City project”, provided by the Dongguan Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources. Data are available with the permission of Dongguan Bureau of Natural Resource).

On this path, the transformation is mainly led by the government. The survey results show that the transformation process not only reduces the negative externalities of the original village-level industrial park, but also protects the village culture through the creation of public space, thus achieving the goal of ecological sustainable development. However, due to the high expectations of villagers as regards demolition fees, the expropriation of large areas of land places short-term financial pressure on local governments, and following the urban economic development model under the land financing strategy may also generate risks of urban expansion [44], and the economic sustainability is affected. At the same time, if the government forcibly intervenes in industrial parks with collective land stock through the strict control of land use, it will inevitably lead to a restructuring of power.

5.2.2. Unified Lease Management Path

The path of unified lease and management is mainly followed in industrial parks that the government believes require transformation, but it is difficult for rural collective economic organizations to select partners, which are required for projects wherein social capital-holders are not willing to intervene in land consolidation in the park, and Lecong Shabian Industrial Park is a typical case of this. Before the transformation, Lecong Shabian Industrial Park was mainly engaged in furniture manufacturing. Due to the age of the factory here, the existing enterprise procedures were not perfect, and the industrial space was in a state of “small, scattered and poor”, resulting in difficulties in land consolidation in the early stage. After the government assists the rural collective economic organization in completing the preliminary land consolidation work through unified leasing and management, the rural collective economic organization will provide land in an open circulation form, after which the bidder will refund the cost of participation in land consolidation in the early stage in an agreed manner. After the transformation, the park will introduce intelligent manufacturing, high-end equipment, and facilitates for biomedicine and other leading industries, with the land use more becoming more intensive and efficient, while some industrial space will be reclaimed, reducing the negative externalities of the park.

On this path, the government regulates the land market with unified leasing and management and supports high-tech industries, and the transformation is led by new users and the government. The survey results show that after state-owned assets are used to intervene in leasing land, as well as its development and construction, the village collective obtains stable rent and the investment risks of enterprises can be reduced; however, in the short term, this may place financial pressure on the government, and the government will face certain development risks. Ecological sustainability will be strengthened, while economic sustainability will be lacking.

5.2.3. Policy Incentive Path

The policy incentive path mainly develops when the government fails to incorporate market factors and needs to stimulate market enthusiasm through particular policies. It is suitable for projects wherein users need “one park, one policy” in order to effectively support the smooth realization of industrial transformation, and Najin Science and Technology Industrial Park is typical of this path. Before the transformation, Najin Science and Technology Industrial Park was dominated by the information technology industry, with insufficient enterprise motivation and capacity for technological business incubation, as it only had a district-level science and technology business incubator. The government issued the “Nagin Science and Technology Industrial Park Measures for Promoting the Development of Innovation and Entrepreneurship of Resident Enterprises” special support policies, aiming to introduce new enterprises, revitalize land resources, and thus enable enterprises to obtain sufficient funds to complete industrial transformation. After the intervention of the government, Naxin Technology Company also independently established an industrial investment fund of CNY 200 million to provide financial support for the settlement of high-tech enterprises, the listing of enterprises, invention patents, etc., which greatly promoted the enthusiasm of innovative enterprises to become involved. Najin Technology has achieved massive transformation from a district-level science and technology business incubator to a national-level incubator in only 4 years.

On this path, the results of the transformation are mainly motivated by the cooperation between the government and enterprises. The survey results show that this path has little impact on the property rights relationship of power subjects, yielding to the influence of market resource allocation and promoting the diversification of investment subjects. Policy incentives are mainly implemented in enterprise cultivation, which has little impact on the external space environment and can better achieve the goal of sustainable development. However, special support policies are targeted and difficult to be widely promoted.

5.2.4. Supervision and Management Path

The supervision and management path mainly develops in village-level industrial parks that have both production factors and policy elements, and only require daily management; it is suitable for projects wherein the government’s lack of supervision of the transformation makes it difficult to implement the policies of village-level industrial parks, which cannot be promoted by transformation. The cases that follow this path in the survey include Longjiang Baoyong Industrial Park and Dongguan Shunchang Industrial Park, of which Longjiang Baoyong Industrial Park is the most representative. Before the transformation, due to the large area of the Longjiang Baoyong Thousand Mu Industrial Park (about 1518 mu) and the huge discrepancy between the acquisition cost and supply price of industrial land, the interests of shareholders could not be balanced; meanwhile, the park was dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises, with complex ownership, and land resources were difficult to use. Given the problems facing the park, the government has actively implemented policies such as collective construction land marketing and transferring industrial resettlement agreements, while also ensuring the continuous participation of village collectives and enterprises in the transformation by delineating industrial brown lines and establishing unified compensation standards. After the transformation, the total investment in the park, including the two village committees of Xiantang and Xinhuaxi, will exceed CNY 10 billion, with 2.05 million square meters of new industrial facilities added, and the annual output value of the project is expected to reach CNY 12 billion after all projects are completed (The undisclosed data are from “Case study of village-level industrial park renovation in Foshan City”, provided by the Foshan Urban Renewal Bureau).

On this path, the transformation is mainly driven by the cooperation of village collectives and enterprises. The survey results show that through the implementation of existing policies, the government can meet the high expectations of village collectives for land use compensation, and at the same time establish a list of enterprises that lack legal procedures, which will continue to ensure the transformation of village-level industrial parks. However, due to the insufficient intervention of government forces, Longjiang Baoyong Thousand Mu Industrial Park currently comprises more small enterprises that are distributed separately, and the industrial operation efficiency in the park is low, resulting in low tax contributions and insufficient economic sustainability.

5.3. Comparison of Transformation Paths Based on the Stewardship of Government

In the participating in the transformation of village-level industrial parks, the lack of different structural factors of the management rights holders may lead to the arising of one of four paths: land expropriation, unified lease management, policy rewards and supervised management. The interests of the management rights holders are mainly to regulate the land market, reduce the negative externalities of the park and improve the efficiency of resource allocation. Therefore, the study concludes that the government’s participation in the transformation of village industrial parks with policy elements will be beneficial to ecological sustainability, but the impact on economic sustainability and social sustainability depends on the results of the game among government departments, village collectives and the market. In the land expropriation path, the ecological sustainability and social sustainability of industrial parks are enhanced because the government regulates land ownership, but the financial pressure brought by the expropriation will affect the economic sustainability; in the unified lease management path, the government advances funds to promote the market and village collectives to cooperate in the transformation, and supports high-tech industries to improve ecological sustainability, but it may also cause financial pressure to affect the economic sustainability; in the policy incentive path, the government provides special policy guidance for In the government guidance path, the government provides special policy guidance for enterprises to improve sustainability in all aspects, but due to the high cost of special policy formulation, the promotion is not strong; in the supervision and management path, the government does not regulate property rights in industrial parks, and the lack of government intervention leads to no significant improvement in sustainability in all aspects (Table 3). Compared with village collectives and market entities, the government pays more attention to macro-economic intervention and the distribution of public benefits [45]. Excessive government involvement may lead to “government failure”, such as with the emergence of differences between government goals and public interests, and inefficient resource allocation [46]. Insufficient government intervention leads to “market failure” problems such as monopoly, negative externalities, information asymmetry, and inefficient industry operation [47].

Table 3.

Basic situations of government participation paths in the research cases.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Urban renewal can be seen as a multi-power collaborative process [35,45]. In order to adapt to the complex urban renewal process, a more systematic and flexible urban renewal model is needed to ensure the benefit distribution, responsibility sharing and sustainable urban development among different power subjects. In the Pearl River Delta, the renovation of village-level industrial parks is driven by the dual forces of “top-down” and “bottom-up” [48], and it is affected by the capital market, the land property rights system, government control and other factors. The village-level industrial park is the urban space with the most complex power subjects [3,49], so it is important to clarify the internal logic of the participation of its power subjects in the transformation.

Therefore, this study aims to deeply analyze the participation mechanisms and paths of power subjects in the transformation of village industrial parks from the perspectives of owners, users and managers, and further summarize the sustainability and applicability of the paths. The conclusions are as follows.

- (1)

- Village collectives, market entities and governments may face a lack of structural elements, such as land, funds and policies, which will lead to 14 renovation paths. The existing studies generally summarize three models of industrial park renovation from the perspective of leading subjects: government-led, market-led and village collective-led [48]. While using “structure-participant” model, more paths can be listed by deeply analyzing the participation mechanism and element mastery of each subject. From the perspective of the owner, the characteristics of ownership are mainly reflected in one of the following five situations: When the village collective lacks market factors, usufruct rights will be established and transferred to developers, operators or enterprises (land leasing); when the village collective lacks policy elements, there will be a change in the ownership subject (government storage). When the village collective has all the structural elements, there is no change in ownership (independent management). From the perspective of the usufruct right holder, the characteristics of the usufruct rights are mainly reflected in one of the following five situations: When market entities lack policy elements, government support will facilitate the extension of the usufruct term. When market entities lack land elements, regular rental will expand the scope of usufruct rights. When there is a lack of labor factors, the introduction of enterprises will lead to an increase in the subject of the usufruct right. When the market entity suffers from a lack of funds and management talent, its elimination upon expiration will lead to a change in the subject of the usufruct right. When market entities have all the structural elements, there is no change in the usufruct right. From the perspective of the jurisdiction holder, the characteristics of the management rights are mainly reflected in one of the following four situations: When the government lacks land elements and market factors, it will participate in renovation through the regulation of ownership rights (land expropriation), the adjustment of ownership and usufruct rights (unified lease management) or the separate adjustment of usufruct rights (policy incentives). In the context of village-level industrial parks with all the required elements, the government only maintains jurisdiction by implementing existing policies (supervision and management).

- (2)

- The sustainability of the village-level industrial park is led by the strongest voice among the village collective, the market entity and the government. The social sustainability under village collective-led path is higher, the economic sustainability of renovation under market-led path, and the ecological sustainability under government-led path. It has been shown that the resources, power and interests held by the dominant power players largely influence the effect of spatial transformation [50]. Thus further affecting the sustainability. For example, in the path of village collective self-management, village collectives with land elements have a greater voice. Their interests of retaining collective land property rights, continuing traditional village industries and preserving local culture are fully satisfied, thus the renovation gains high social sustainability.

- (3)

- Different transformation paths are applied in different contexts, and should be chosen according to the basic conditions and transformation goals of village industrial parks. Market-led paths, such as elimination upon expiration, the introduction of enterprises, autonomous operations and unified lease management, are applicable when greater economic sustainability, enhancements in space production functions and industrial upgrading are pursued in the renovation. The paths dominated by the village collective, such as land leasing, independent management and routine supervision, can be adopted when the village industrial park needs to ensure social sustainability and there are regional characteristics, customs, cultures and traditional industries that need to be preserved. Government-led paths, such as government storage and land expropriation, can be chosen when a fairer distribution of public resources and an increase in public services are required, as well as hopes to reduce the negative externalities and enhance the ecological sustainability.

The main theoretical contributions of this study is that we proposed a more systematic, comprehensive and universal framework for the participation paths of property right actors in village-level industrial parks. Compared with empirical research on a single case, this study compared and discussed the macro conditions of rural industrialization in the Pearl River Delta region, reasonably distinguished the relevant objects and conditions of different paths, and coordinated land, capital, management talents, labor, policies and other elements to establish a complete system of available renovation paths. Under the context of ownership by the people, this study explored how property right actors with different means of production cooperate, and how best to distribute land resources in relation to complex property rights, thus enriching the research on urban renewal theory, and providing much-improved research methods and concepts related to the complexities of power in urban renewal. As for the Practical implications, the study investigates the pre-renovation conditions, renovation methods and effects of the representative cases of each path and analyzes their sustainability, summarizing the applicable contexts of different paths. It provides a basis for path selection for future industrial park renovation and sustainable urban renewal practices, enhancing the rationality of decision making.

Although this study provides practical insights relevant to the renovation of village-level industrial parks, some aspects still need to be improved. Firstly, regarding the “structure–participant” structural model itself, the path analysis method based on case analysis has certain limitations in the study of sustainable development, Future research should scientifically evaluate the sustainability of the renovation paths and find out the influencing factors through quantitative methods. Secondly, some village-level industrial parks in China contain both collective land and state-used land. Therefore the participation and power relations are more complex than is suggested by theoretical approaches. The selection of empirical cases in the future research should pay more attention to the village-level industrial parks mixed with collective land and state-owned land, and explore their sustainable development path. Finally, given that the cases and data are from China, the results can thus only reflect the power and resources of stakeholders in village-level industrial park renovation in China. the conditions of which are significantly different from those of other countries where land is privatized. Future research should compare the renovation paths in the context of different land systems to provide a more universal experience for the sustainable renewal of industrial land worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.; data curation, S.Z. and J.Y.; formal analysis, S.Z. and J.Y.; funding acquisition, S.Z. and C.Y.; investigation, S.Z., J.Y. and Y.L.; methodology, C.Y. and S.Z.; project administration, C.Y.; resources, S.Z.; supervision, C.Y. and W.C.; validation, J.Y., C.Y. and W.C.; visualization, S.Z.; writing—original draft, S.Z. and J.Y.; writing—review & editing, J.Y. and W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Provincial “Research on community integration, mechanism and strategies of the accompanying elderly”, grant number 2023A1515012861; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, “The impact and evolution processes of urban renewal on social equity of public space from supply-demand perspective”, grant number 41871156; and Special Funds for the Cultivation of Guangdong College Students’ Scientific and Technological Innovation (“Climbing Program” Special Funds), grant number pdjh2023a0078.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to the fact that they contain confidential government data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, B.; Tian, L.; Yao, Z. Institutional uncertainty, fragmented urbanization and spatial lock-in of the peri-urban area of China: A case of industrial land redevelopment in Panyu. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Yang, M. Urbanization, economic growth and environmental pollution: Evidence from China. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2019, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, Y. Research on Planning Policies of Concentration of Fragmented Industrial Points in the Rural Pearl River Delta: A Case of Industrial Parks of Panyu District, Guangzhou. Urban Plan. Forum 2010, 2, 21–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Hui, E.; Lang, W.; Li, X. Land Ownership, Rent-Seeking, and Rural Gentrification: Reconstructing Villages for Sustainable Urbanization in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X. Evolution of Rural Industrial Land Use in Semi-urbanized Areas and Its Multi-dynamic Mechanism:A Case Study of Shunde District in Foshan City. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redclift, M. Sustainable Development (1987–2005): An Oxymoron Comes of Age. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, C.A. Sustainability and Sustainable Development: A Review of Principles and Definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development, and Gro Harlem Brundtland. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1987; pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Khaiter, P.A.; Erechtchoukova, M.G. (Eds.) Sustainability Perspectives: Science, Policy and Practice, 1st ed.; Springer Nature Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; 362p, ISBN 978-3-030-19550-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; de Vries, W.T. Collective Action for the Market-Based Reform of Land Element in China: The Role of Trust. Land 2022, 11, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y. Rural Industrialization Pattern and Rural Land System Change: A Study on the System of Collective Construction Land in Coastal Areas. China Rural Econ. 2020, 4, 101–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Q. The Marketization Path of Collective Asset Management and Its Practical Paradox. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 8, 17–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Darwent, D.F. Growth Poles and Growth Centers in Regional Planning—A Review. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 1969, 1, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoviz, A.V.; Shkodinsky, S.V.; Skomoroshchenko, A.A.; Mishchenko, I.V.; Malyutina, T.D. Scenarios of Development of the Modern Global Economy with Various Growth Poles. In Growth Poles of the Global Economy: Emergence, Changes and Future Perspectives; Popkova, E.G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 73, pp. 185–192. ISBN 978-3-030-15159-1. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, J.B. Growth Poles, Regional Development, and Central Place Theory. In Proceedings of the Papers of the Regional Science Association; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1973; Volume 31, pp. 173–212. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z. Recycling Utilization Patterns of Coal Mining Waste in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunmakinde, O.E.; Egbelakin, T.; Sher, W. Contributions of the Circular Economy to the UN Sustainable Development Goals through Sustainable Construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chi, G.; Wang, G.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Ju, C. Untangle the Complex Stakeholder Relationships in Rural Settlement Consolidation in China: A Social Network Approach. Land 2020, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mohabir, N.; Ma, R.; Wu, L.; Chen, M. Whose village? Stakeholder interests in the urban renewal of Hubei old village in Shenzhen. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, H. Do ambiguous property rights matter? Collective value logic in Lin Village. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z. Interpreting non-conforming urban expansion from the perspective of stakeholders’ decision-making behavior. Habitat Int. 2019, 89, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, G.; Roe, M. Institutional stakeholder participation in urban redevelopment in Tehran: An evaluation of decisions and actions. Land Use Policy 2019, 91, 104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Sun, S.J.; Li, J.G. The dawn of vulnerable groups: The inclusive reconstruction mode and strategies for urban villages in China. Habitat Int. 2021, 110, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Geertman, S.; van Oort, F.; Lin, Y. Making the “Invisible’ Visible: Redevelopment-induced Displacement of Migrants in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Tian, C. Removal and reconstruction: Multi-period price effects on nearby housing from urban village redevelopment. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, H.; Ma, L.; Tu, S.; Liao, L.; Chen, K.; Xu, Z. How does the community resilience of urban village response to the government-led redevelopment? A case study of Tangjialing village in Beijing. Cities 2019, 95, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kidokoro, T.; Onishi, T. Research on Development Control from Perspective of New Institutionalism: Based on An Analysis of Impact Factors of Housing Development Index Adjustment in the “Structure-Participants” Model. City Plan. Rev. 2013, 37, 29–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Ge, D.; Sun, P.; Sun, D. The Transition Mechanism and Revitalization Path of Rural Industrial Land from a Spatial Governance Perspective: The Case of Shunde District, China. Land 2021, 10, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.A.; Wang, Y. Institutional Analysis: An Approach for the Study of Real Estate Development Processes. Urban Plan. Overseas 2002, 1, 41–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Yajie, L.; Qin, L. An Explorative Study on Implementation Effects and Spatial Patterns of Urban Renewal Practices in Shenzhen from 2010 to 2016. Urban Plan. Forum 2018, 3, 86–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Li, S.; Zhuang, L.; Zhu, X. A comparison and case analysis between domestic and overseas industrial parks of China since the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Fei, Y. Guangzhou Urban Regeneration and Spatial Innovation. Planners 2019, 35, 46–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Wu, W.; Zhuang, T.; Yi, Y. Exploring the Diverse Expectations of Stakeholders in Industrial Land Redevelopment Projects in China: The Case of Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; Zhu, Z.; Chen, L., Translators; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, C.W.; Douglas, P.H. A Theory of Production. Am. Econ. Rev. 1928, 18, 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Huang, X.; Zhu, H. Interpretation of 798: Changes in Power of Representation and Sustainability of Industrial Landscape. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5282–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Q. Redevelopment of Village Built-up Land under the Welfare-oriented Village Cooperatives: A Case Study of Nanhai District, Pearl River Delta. Mod. Urban Res. 2016, 12, 69–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Qian, T.; Yang, L. Involution Constraints Perspectives on the Old Village’s Renovation in the Pearl River Delta: A Case Study of XB Village in Nanhai, Foshan. Mod. Urban Res. 2016, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Yuan, Q. Social Equity Between Villages Under Capitalization of Collectively-Owned Land and Its Impact on Urban Inclusivity. Urban Dev. Stud. 2016, 23, 67–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.F. The reterritorialization of business- trade urban villages by the migrant workers: A case study of Kangle Village of Guangzhou City. Urban Probl. 2016, 11, 42–46+76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Land market forces and government’s role in sprawl: The case of China. Cities 2000, 17, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W.; Song, Y. Impacts of land finance on urban sprawl in China: The case of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.; Visscher, H.; Elsinga, M. Stakeholders’ Expectations in Urban Renewal Projects in China: A Key Step towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Cai, Q.; Huang, Y.; Lang, W. System Building and Multistakeholder Involvement in Public Participatory Community Planning through Both Collaborative- and Micro-Regeneration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, D. “Market Failure” and “Government Failure” in the Process of Urban Village Improvement and Countermeasures. Urban Probl. 2008, 10, 47–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; He, Z.; Ma, H. Comparison of Collective-Led and State-Led Land Development in China from the Perspective of Institutional Arrangements: The Case of Guangzhou. Land 2022, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Tian, L. How did collectivity retention affect land use transformation in peri-urban areas of China? A case of Panyu, Guangzhou. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Space Reproduction in Urban China: Toward a Theoretical Framework of Urban Regeneration. Land 2022, 11, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).