Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety: Mediating Effects with Moderation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety

1.2. The Mediating Effect of Appearance Anxiety

1.3. The Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem

1.4. The Moderating Effect of Gender

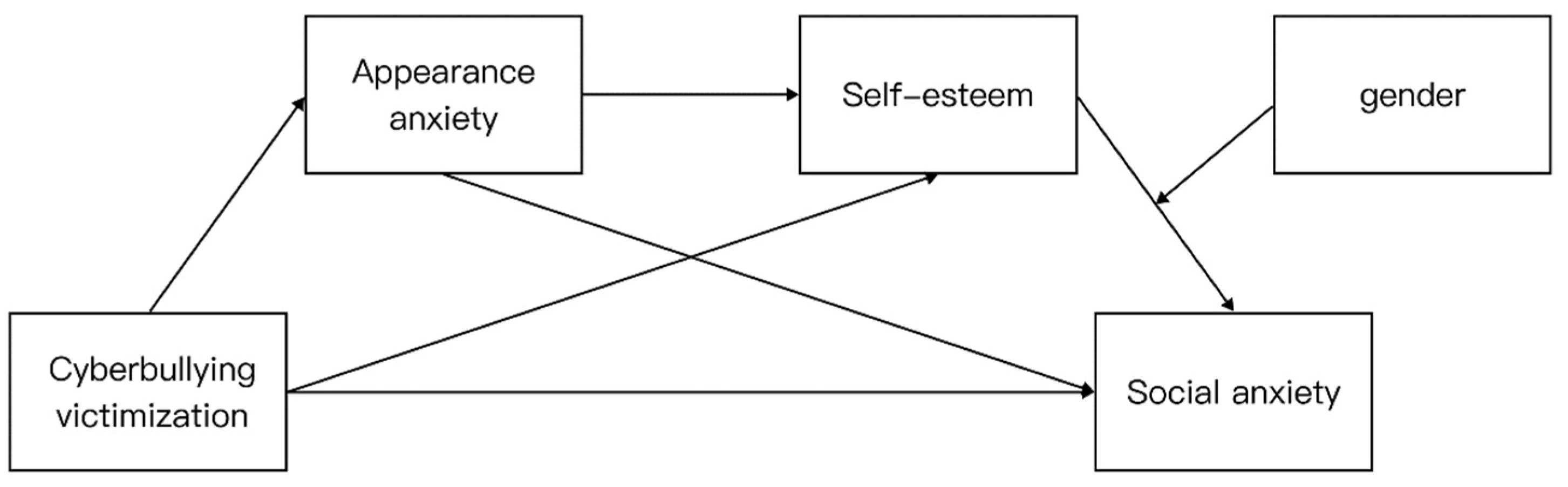

1.5. Purpose of the Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Power Analysis

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Cyberbullying Inventory

2.3.2. The Social Appearance Anxiety Scale

2.3.3. Self-Esteem Scale

2.3.4. Social Anxiety Scale

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Common Method Bias Test and Validity Distinction

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Mediating Effect Test

3.3. Moderated Mediation Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Cyberbullying on College Students’ Social Anxiety

4.2. The Mediating Role of Appearance Anxiety

4.3. The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem

4.4. The Serial Mediating Effect of Appearance Anxiety and Self-Esteem

4.5. Gender Moderation

4.6. Research Suggestions and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 49th “Statistical Report on Internet Development in China”. Available online: http://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2022/0401/c88-1131.html (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Lucero, J.; Weisz, A.; Smith-Darden, J.; Lucero, S. Exploring Gender Differences: Socially Interactive Technology Use/Abuse Among Dating Teens. Affilia 2014, 29, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, R.S. Following You Home from School: A Critical Review and Synthesis of Research on Cyberbullying Victimization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Frias Butrón, C. Systematic Review of Empirical Studies on Cyberbullying in Adults: What We Know and What We Should Investigate. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 38, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhong, Z.; Zheng, W.; Gao, X. The Relationship between the Big Five and Cyberbullying among College Students: The Mediating Effect of Moral Disengagement. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Boyle, M.H.; Georgiades, K. Cyberbullying Victimization and Its Association with Health across the Life Course: A Canadian Population Study. Can. J. Public Health 2017, 108, e468–e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, V.A.; Romão, A.M. The Relation between Social Anxiety, Social Withdrawal and (Cyber)Bullying Roles: A Multilevel Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, S. Cyberbullying and Depression among Chinese College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model of Social Anxiety and Neuroticism. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderka, I.M.; Hofmann, S.G.; Nickerson, A.; Hermesh, H.; Gilboa-Schechtman, E.; Marom, S. Functional Impairment in Social Anxiety Disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Yang, H.-J.; Kim, S.-G.; Yoon, H.-J. Ego-Resiliency Moderates the Risk of Depression and Social Anxiety Symptoms on Suicidal Ideation in Medical Students. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2022, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İçellioğlu, S.; Özden, M.S. Cyberbullying: A New Kind of Peer Bullying through Online Technology and Its Relationship with Aggression and Social Anxiety. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 4241–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heimberg, R.G.; Brozovich, F.A.; Rapee, R.M. Chapter 15—A Cognitive Behavioral Model of Social Anxiety Disorder: Update and Extension. In Social Anxiety, 2nd ed.; Hofmann, S.G., DiBartolo, P.M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 395–422. ISBN 978-0-12-375096-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Rudolph, J.; Webb, H.J.; Henderson, L.; Hawes, T. Face-to-Face and Cyber-Victimization: A Longitudinal Study of Offline Appearance Anxiety and Online Appearance Preoccupation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 2311–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawijit, Y.; Likhitsuwan, W.; Ludington, J.; Pisitsungkagarn, K. Looks Can Be Deceiving: Body Image Dissatisfaction Relates to Social Anxiety through Fear of Negative Evaluation. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2017, 31, 20170031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.T.Q.; Gu, P. Chuanhua Cyberbullying Victimization and Depression: Self-Esteem as a Mediator and Approach Coping Strategies as Moderators. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 71, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holas, P.; Kowalczyk, M.; Krejtz, I.; Wisiecka, K.; Jankowski, T. The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Self-Compassion in Socially Anxious. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 10271–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.; Asnaani, A.; Aderka, I.M. Gender Differences in Social Anxiety Disorder: A Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W.; Arslan, R.C.; Denissen, J.J.A.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Gebauer, J.E.; Potter, J.; Gosling, S.D. Age and Gender Differences in Self-Esteem—A Cross-Cultural Window. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, A.S.; Heimberg, R.G. Social Anxiety and Social Anxiety Disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, X.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Li, C.; Cui, L. Cognitive Bias Modification for Interpretation Training via Smartphones for Social Anxiety in Chinese Undergraduates. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 2019, 10, 204380871987527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, M.; Spears, B.; Slee, P.; Butler, D.; Kift, S. Victims’ Perceptions of Traditional and Cyberbullying, and the Psychosocial Correlates of Their Victimisation. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2012, 17, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the Digital Age: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of Cyberbullying Research among Youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.; Clark, D.M.; Salkovskis, P.; Ludgate, J.; Hackmann, A.; Gelder, M. Social Phobia: The Role of in-Situation Safety Behaviors in Maintaining Anxiety and Negative Beliefs. Behav. Ther. 1995, 26, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.A.; Flora, D.B.; Palyo, S.A.; Fresco, D.M.; Holle, C.; Heimberg, R.G. Development and Examination of the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale. Assessment 2008, 15, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, J.; Martin, A. Appearance Teasing and Mental Health: Gender Differences and Mediation Effects of Appearance-Based Rejection Sensitivity and Dysmorphic Concerns. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, W.; Jackson, M.; Brown, K.N. Sticks and Stones Can Break My Bones, but How Can Pixels Hurt Me?: Students’ Experiences with Cyber-Bullying. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2009, 30, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mishna, F.; Cook, C.; Gadalla, T.; Daciuk, J.; Solomon, S. Cyber Bullying Behaviors among Middle and High School Students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kenny, U.; Sullivan, L.; Callaghan, M.; Molcho, M.; Kelly, C. The Relationship between Cyberbullying and Friendship Dynamics on Adolescent Body Dissatisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.M.; Wells, A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment; Heimberg, R.G., Liebowitz, M.R., Hope, D.A., Schneier, F.R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, C.A.; Rodebaugh, T.L. Validation of the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale: Factor, Convergent, and Divergent Validity. Assessment 2011, 18, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neziroglu, F.; Khemlani-Patel, S.; Veale, D. Social Learning Theory and Cognitive Behavioral Models of Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Body Image 2008, 5, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, J.; Wolfe, C.T. Contingencies of self-worth. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 593–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Gallagher, B.; Fors, E.; Buttermore, N.; Baldwin, E.; Kennedy KMills, A. The invalidity of disclaimers about the effects of social feedback on self-esteem. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Banaji, M.R. Implicit Social Cognition: Attitudes, Self-Esteem, and Stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, D.B.; Wood, J.V.; Holmes, J.G. Testing Sociometer Theory: Self-Esteem and the Importance of Acceptance for Social Decision-Making. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Campbell, J.D.; Krueger, J.I.; Vohs, K.D. Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2003, 4, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeigler-Hill, V.; Li, H.; Masri, J.; Smith, A.; Vonk, J.; Madson, M.B.; Zhang, Q. Self-Esteem Instability and Academic Outcomes in American and Chinese College Students. J. Res. Pers. 2013, 47, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousis, I. The Relationship of Self-Esteem to Bullying Perpetration and Peer Victimization among Schoolchildren and Adolescents: A Meta-Analytic Review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 31, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L. How Does Sexual Minority Stigma “Get Under the Skin”? A Psychological Mediation Framework. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mereish, E.H.; Peters, J.R.; Yen, S. Minority Stress and Relational Mechanisms of Suicide among Sexual Minorities: Subgroup Differences in the Associations Between Heterosexist Victimization, Shame, Rejection Sensitivity, and Suicide Risk. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Shi, C. The Relationship Between Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy and Core Self-Evaluation of College Students: The Mediation Effects of Suicidal Attitude. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowles, T.V. The Focus of Intervention for Adolescent Social Anxiety: Communication Skills or Self-Esteem. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 5, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, T.S.; Steffens, M.C.; Ritter, V.; Stangier, U. On the Context Dependency of Implicit Self-Esteem in Social Anxiety Disorder. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2017, 57, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mares, S.H.W.; de Leeuw, R.N.H.; Scholte, R.H.J.; Engels, R.C.M.E. Facial Attractiveness and Self-Esteem in Adolescence. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2010, 39, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, R.W.; Trzesniewski, K.H.; Tracy, J.L.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Global Self-Esteem across the Life Span. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Schneier, F.; Heimberg, R.G.; Princisvalle, K.; Liebowitz, M.R.; Wang, S.; Blanco, C. Gender Differences in Social Anxiety Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Sample on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmark, T. Social Phobia: Overview of Community Surveys. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2002, 105, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehm, L.; Pelissolo, A.; Furmark, T.; Wittchen, H.-U. Size and Burden of Social Phobia in Europe. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Jong, P.J. Implicit Self-Esteem and Social Anxiety: Differential Self-Favouring Effects in High and Low Anxious Individuals. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, P.J.; Sportel, B.E.; de Hullu, E.; Nauta, M.H. Co-Occurrence of Social Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Adolescence: Differential Links with Implicit and Explicit Self-Esteem? Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdur-Baker, O.; Kavsut, F. Cyber Bullying: A New Face of Peer Bullying. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2007, 27, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.-Y.; Chu, X.-W.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.-K. Are Narcissists More Likely to Be Involved in Cyberbullying? Examining the Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 3127–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tang, H.; Tian, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhang, F.; Morrison, C.M. Cyberbullying and Its Risk Factors among Chinese High School Students. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2013, 34, 630–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES); Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. The Relationship between Contingent Self-Esteem and Trait Self-Esteem. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, X. The Applicabiliy of Interaction Anxiousness Scale in Chinese Undergraduate Students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2004, 18, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L.-R. Statistical Remedies for Common Method Biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R. Social Anxiety as an Early Warning System; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 471–486. [Google Scholar]

- Hook, J.N.; Valentiner, D.P. Are Specific and Generalized Social Phobias Qualitatively Distinct? Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2002, 9, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popat, A.; Tarrant, C. Exploring Adolescents’ Perspectives on Social Media and Mental Health and Well-Being—A Qualitative Literature Review. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.-A. Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; Tylka, T.L.; Rodgers, R.F.; Convertino, L.; Pennesi, J.-L.; Parent, M.C.; Brown, T.A.; Compte, E.J.; Cook-Cottone, C.P.; Crerand, C.E.; et al. Pathways from Sociocultural and Objectification Constructs to Body Satisfaction among Men: The U.S. Body Project I. Body Image 2022, 41, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, K.; Caltabiano, N. Cyberbullying and Self-Esteem in Australian Adults. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2014, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchilli, T.L.; Valerio, C.Y. The Knowledge and Prevalence of Cyberbullying in a College Sample. J. Sci. Psychol. 2011, 5, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski, K.H.; Donnellan, M.B.; Robins, R.W. Stability of self-esteem across the life span. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.E.; Tyler, J.M.; Calogero, R.; Lee, J. Exploring the Relationship between Appearance-Contingent Self-Worth and Self-Esteem: The Roles of Self-Objectification and Appearance Anxiety. Body Image 2017, 23, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Baumeister, R.F. The Nature and Function of Self-Esteem: Sociometer Theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; Volume 32, pp. 1–62. ISBN 978-0-12-015232-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, M.; Li, C.; Hall, J.A. When Men and Women Differ in Self-Esteem and When They Don’t: A Meta-Analysis. J. Res. Pers. 2016, 64, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Nakajima, M.; Ibañez-Tallon, I.; Heintz, N. A Cortical Circuit for Sexually Dimorphic Oxytocin-Dependent Anxiety Behaviors. Cell 2016, 167, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fanti, K.; Demetriou, A.; Hawa, V. A Longitudinal Study of Cyberbullying: Examining Riskand Protective Factors. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Swearer, S.M. Four Decades of Research on School Bullying: An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.; Duval, E. Social Interaction Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Are Differentially Related in Men and Women. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 2. Cyberbullying victimization | 1.28 | 0.32 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.72 | |||

| 3. Appearance Anxiety | 2.85 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 0.34 ** | 0.76 | ||

| 4. Self-esteem | 2.84 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 0.54 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.26 ** | 0.74 | |

| 5. Social anxiety | 3.36 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.14 * | 0.43 ** | −0.33 ** | 0.73 |

| Appearance Anxiety | Self-Esteem | Social Anxiety | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | |

| constant | 1.68 | 0.22 | 7.78 *** | 3.17 | 0.13 | 23.87 *** | 3.44 | 0.27 | 12.78 *** |

| Cyberbullying victimization | 0.91 | 0.16 | 5.63 *** | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.24 |

| Appearance anxiety | −0.15 | −0.15 | −4.27 *** | 0.24 | 0.04 | 5.85 *** | |||

| Self-esteem | −0.28 | 0.07 | −3.89 *** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.24 | ||||||

| F | 31.72 | 9.30 | 24.42 | ||||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Relative Mediation Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 90.12% |

| Ind1: Cyberbullying victimization → appearance anxiety → social anxiety | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 84.12% |

| Ind2: Cyberbullying victimization → self-esteem → social anxiety | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 | - |

| Ind3: Cyberbullying victimization → appearance anxiety → self-esteem → social anxiety | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 14.94% |

| Appearance Anxiety | Self-Esteem | Social Anxiety | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | |

| constant | 1.68 | 0.22 | 7.78 *** | 3.17 | 0.13 | 23.87 *** | 1.73 | 0.72 | 2.43 * |

| Cyberbullying victimization | 0.91 | 0.16 | 5.63 *** | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.10 | −0.13 |

| Appearance anxiety | −0.15 | −0.15 | −4.27 *** | 0.23 | 0.04 | 5.81 *** | |||

| Self-esteem | 0.30 | 0.24 | 1.22 | ||||||

| Gender | 1.07 | 0.41 | 2.58 * | ||||||

| Self-esteem X Gender | −0.35 | 0.14 | −2.45 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.26 | ||||||

| F | 31.72 | 9.30 | 16.34 | ||||||

| Gender | Boot Indirect Effect | Boot SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Male | 0.0074 | 0.0205 | −0.0261 | 0.0537 |

| Female | 0.0562 | 0.0217 | 0.0211 | 0.1063 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, T.; Liao, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, L. Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety: Mediating Effects with Moderation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139978

Xia T, Liao J, Deng Y, Li L. Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety: Mediating Effects with Moderation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139978

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Tiansheng, Jieying Liao, Yiting Deng, and Linli Li. 2023. "Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety: Mediating Effects with Moderation" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139978

APA StyleXia, T., Liao, J., Deng, Y., & Li, L. (2023). Cyberbullying Victimization and Social Anxiety: Mediating Effects with Moderation. Sustainability, 15(13), 9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139978