How Do Urban Walking Environments Impact Pedestrians’ Experience and Psychological Health? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

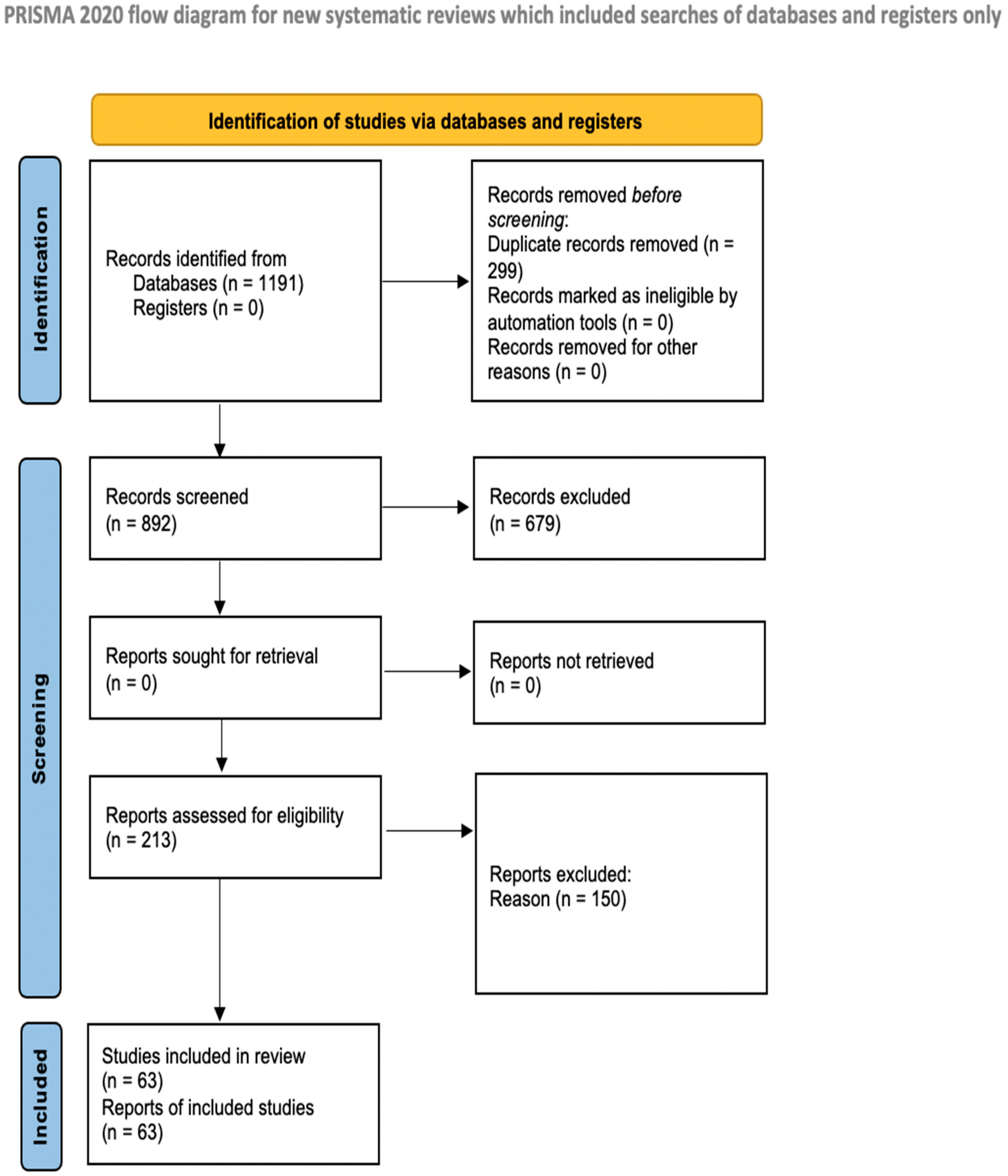

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

- (1)

- The area investigated was (a) a microscale (b) urban outdoor environment. Indoor environments were therefore excluded. Although this article is focused on the micro level, we included certain factors that could be argued to exist on a mesoscale level, such as distance and density. However, from a pedestrian perspective, a dense environment is apparent even on a micro-scale level (Table 1). Likewise, a long distance can mean a lack of a specific attribute in the micro-scale area. Thus, the attributes that a pedestrian can experience in a small (micro) area were included in the paper even if it could be experienced on a meso-scale or even a macro-scale as well. Regarding the term “urban”, we used the definitions that had been used in the articles; thus, the meaning may differ between publications. If the area was not clearly urban, it was excluded. ‘Semi-rural’ study areas were not included, for example.

- (2)

- The publication focused on walkability or ‘walking’ from a pedestrian’s perspective (Table 1). Therefore, all papers included in our systematic review contained human measurements (actual participants). Additionally, the number of participants must have been specified. Thus, if walkability or walking was measured in a certain paper only with other means (such as GIS), the paper was excluded. As well, ‘view from a window’ studies have been excluded, as the pedestrian perspective would then be missing. However, when typical pedestrian attributes were in focus, such as sidewalks, benches, crosswalks, and other attributes, walking was judged to be implicit, and these publications were included, even if walkability or walking was not explicit. However, papers with only “cyclability” or other kinds of transport were excluded. Instead of walkability or walking, other expressions were sometimes used in the papers, such as “pedestrians”, or “physical activity”, and such a paper was included. Discussions of wheelchair use instead of walking have also been included.

- (3)

- The publication focused on the impact on psychological experience or health (long and short term) in a wide sense (Table 1). Everything from ‘simple’ psychological reactions that are aroused at the moment to long-term psychiatric diagnoses have been included. The measured health variables included affect, experience, comfort, enjoyment, happiness, psychological response, mood response, satisfaction, well-being, quality of life, psychological distress, psychosocial distress, creativity, depression, anxiety, and mental health. Safety and security have been included, as well as fear. Additionally, stress-related responses such as restorativeness or tension have been included. Physiological reactions have been included when they were stress related, such as cortisol levels and heart rate.

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Factors

3.1.1. “Grey” Areas

3.1.2. Green Areas

3.1.3. Blue Areas

3.1.4. White Areas, Weather, and Temperature

3.1.5. Topography

3.2. Temporalities

3.3. Person Factors

Safety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Log of the Search Process: Search Terms, Number of Studies Found, and Date of the Search

| Database | Search Words | No. of Studies Exported to EndNote | Last Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| Science Direct | urban AND micro scale AND physical environment AND walkability AND well-being | 398 | June 2022 |

| Scopus | “ | 0 | “ |

| Pubmed | “ | 0 | “ |

| PsychInfo | “ | 0 | “ |

| Google Scholar | “ | 50 first | “ |

| Science Direct | urban AND micro scale AND physical environment AND walkability AND mental health | 546 | 1 July 2022 |

| Scopus | “ | 0 | “ |

| Pubmed | “ | 0 | “ |

| PsychInfo | “ | 0 | “ |

| Google Scholar | “ | 50 first | “ |

| Science Direct | urban AND physical environment AND walkability AND well being | 54 | “ |

| Science Direct | urban AND micro scale AND physical environment AND walkability AND well-being | 40 | 6 July 2022 |

| Scopus | “ | 0 | “ |

| Pubmed | “ | 3 | “ |

| PsychInfo | “ | 0 | “ |

| Google Scholar | “ | 50 first | “ |

| Duplicates found: 299. The total sum of publications: 892. | |||

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospect. The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, N.A.; Booth, G.L. The Weight of Place: Built Environment Correlates of Obesity and Diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 966–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.; Ottosson, J.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. The Oxytocinergic System as a Mediator of Anti-stress and Instorative Effects Induced by Nature: The Calm and Connection Theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 617814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seresinhe, C.I.; Preis, T.; MacKerron, G.; Moat, H.S. Happiness is greater in more scenic locations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundling, C.; Ceccato, V. The impact of rail-based stations on passengers’ safety perceptions. A systematic review of international evidence. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2022, 86, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, A.K. Urban streets: Towards a psychological restorative function. In Proceedings of the 2nd Future of Places International Conference on Public Space and Placemaking (Ed.), Streets as Public Spaces and Drivers of Urban Prosperity, Stockholm, Sweden, 1–3 September 2013; pp. 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.S.; Wheeler, B.W.; White, M.P.; Economou, T.; Osborne, N.J. Research note: Urban street tree density and antidepressant prescription rates—A cross-sectional study in London, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, A.; Morris, G.; Curtice, J.; Robertson, C.; Allardice, G.; Robertson, R. Associations between health and different types of environmental incivility: A Scotland-wide study. Public Health 2009, 123, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, P.; Mehta, V.; Brindley, P.; Zandieh, R. The restorative potential of commercial streets. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz, P.; Olsson, K.S.E.; Eriksson, J.S.; Rosdahl, H. Perspectives on exercise intensity, volume, step characteristics and health outcomes in walking for transport. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 911863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; IPCC. AR Synthesis Report 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS. 2019. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Sarkar, C.; Webster, C. Urban environments and human health: Current trends and future directions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 25, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.; Thorne, A.; Guite, H. The impact on mental well-being of the urban and physical environment: An assessment of the evidence. J. Public Ment. Health 2004, 3, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Palmer, S.; Gallacher, J.; Marsden, T.; Fone, D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krefis, A.C.; Augustin, M.; Schlünzen, K.H.; Oßenbrügge, J.; Augustin, J. How does the urban environment affect health and well-being? A systematic review. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Rethinking how built environments influence subjective well-being: A new conceptual framework. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2017, 11, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 2021, 115, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckney, P.; Bentley, R. The urban public realm and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbø, E.C.; Nordh, H.; Raanaas, R.K.; Aamodt, G. Promoting activity participation and well-being among children and adolescents: A systematic review of neighborhood built-environment determinants. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 370–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Lilli, A.; Lilli, M.A.; Nikolaidis, N.P. On the impact of nature-based solutions on citizens’ health & well being. Energy Build. 2020, 229, 110527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Fors, H.; Lindgren, T.; Wiström, B. Perceived personal safety in relation to urban woodland vegetation—A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, S.M.; Lindley, S.; Huck, J.J. Spatial dimensions of the influence of urban green-blue spaces on human health: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2020, 180, 108869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Georgiou, M.; King, A.C.; Tieges, Z.; Webb, S.; Chastin, S. Urban blue spaces and human health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies. Cities 2021, 119, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankey, S.; Marshall, J.D. Urban form, air pollution, and health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajrasoulih, A.; del Rio, V.; Edmondson, J. Urban form and mental wellbeing: Scoping a theoretical framework for action. J. Urban Des. Ment. Health 2018, 5, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zumelzu, A.; Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G. Mental Well-Being and the Influence of Place: Conceptual Approaches for the Built Environment for Planning Healthy and Walkable Cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, A.; Dill, J.; Luhr, G.; Neal, M. Unpacking Walkability: Testing the Influence of Urban Design Features on Perceptions of Walking Environment Attractiveness. J. Urban Des. 2012, 17, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanyu, K. Visual Properties and Affective Appraisals In Residential Areas In Daylight. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.B.; Harvey, A. Explaining the Emotion People Experience in Suburban Parks. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Kunz, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Antes, G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonzo, M.; Boarnet, M.G.; Day, K.; Mcmillan, T.; Anderson, C.L. The Relationship of Neighbourhood Built Environment Features and Adult Parents’ Walking. J. Urban Des. 2008, 13, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of urban parks and their relation to user well-being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrainy, H.; Khosravi, H. The impact of urban design features and qualities on walkability and health in under-construction environments: The case of Hashtgerd New Town in Iran. Cities 2013, 31, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Lampkin, S.; Dawkins, L.; Williamson, D. Shared space: Negotiating sites of (un)sustainable mobility. Geoforum 2021, 127, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereitschaft, B. Exploring perceptions of creativity and walkability in Omaha, NE. City Cult. Soc. 2019, 17, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglieri, S.; Dean, J. Everyday built environments of care: Examining the socio-spatial relationalities of suburban neighbourhoods for people living with dementia. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Parkhurst, G.; Morgan, P.L. Affective experiences of built environments and the promotion of urban walking. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 123, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancato, G.; Van Hedger, K.; Berman, M.G.; Van Hedger, S.C. Simulated nature walks improve psychological well-being along a natural to urban continuum. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.B.; Werner, C.M.; Amburgey, J.W.; Szalay, C. Walkable route perceptions and physical features: Converging evidence for en route walking experiences. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 34–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, G.; Guzman, V.; Kobayashi, L.C.; Finlay, J. Mental health and well-being in times of COVID-19: A mixed-methods study of the role of neighborhood parks, outdoor spaces, and nature among US older adults. Health Place 2022, 76, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambra, P.; Moura, F. How does walkability change relate to walking behavior change? Effects of a street improvement in pedestrian volumes and walking experience. J. Transp. Health 2020, 16, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X. How does neighborhood design affect life satisfaction? Evidence from Twin Cities. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-S.; Si, F.H.; Marafa, L.M. Indicator development for sustainable urban park management in Hong Kong. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.T.H.; Li, T.E.; Schwanen, T.; Banister, D. People and their walking environments: An exploratory study of meanings, place and times. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2021, 15, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Fu, E.-K.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.-X.; Huang, Z.; Cai, S.-Z.; Jia, Y. Empirical study of landscape types, landscape elements and landscape components of the urban park promoting physiological and psychological restoration. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Switsers, L.; Mundó, J.; Dierckx, E.; Dury, S.; De Donder, L. The association between perceived social and physical environment and mental health among older adults: Mediating effects of loneliness. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzyuban, Y.; Hondula, D.; Vanos, J.; Middel, A.; Coseo, P.; Kuras, E.; Redman, C. Evidence of alliesthesia during a neighborhood thermal walk in a hot and dry city. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 834, 155294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.M. ‘Walk like a penguin’: Older Minnesotans’ experiences of (non)therapeutic white space. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 198, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.M.; Manning, M.; Ambrey, C.L. Crime, greenspace and life satisfaction: An evaluation of the New Zealand experience. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 149, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Wood, L.; Christian, H.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B. Planning safer suburbs: Do changes in the built environment influence residents’ perceptions of crime risk? Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, S.; Wood, L.; Francis, J.; Knuiman, M.; Villanueva, K.; Giles-Corti, B. Suspicious minds: Can features of the local neighbourhood ease parents’ fears about stranger danger? J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Wood, L.J.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B. Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between Public Open Space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Ahern, J.; Rudenstine, S.; Wallace, Z.; Vlahov, D. Urban built environment and depression: A multilevel analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlöf-Gunnarsson, A.; Öhrström, E. Noise and well-being in urban residential environments: The potential role of perceived availability to nearby green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Chan, O.F.; Chui, C.H.K.; Lum, T.Y.S. Objective and perceived built environment, sense of community, and mental wellbeing in older adults in Hong Kong: A multilevel structural equation study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 209, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G.; Mora, R.; Vejares, P. Perception of the built environment and walking in pericentral neighbourhoods in Santiago, Chile. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høj, S.B.; Paquet, C.; Caron, J.; Daniel, M. Relative ‘greenness’ and not availability of public open space buffers stressful life events and longitudinal trajectories of psychological distress. Health Place 2021, 68, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntti, M.; Lundy, L. A mixed methods approach to urban ecosystem services: Experienced environmental quality and its role in ecosystem assessment within an inner-city estate. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 161, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntti, M.; Costa, H.; Nascimento, N. Urban environmental quality and wellbeing in the context of incomplete urbanisation in Brazil: Integrating directly experienced ecosystem services into planning. Prog. Plan. 2021, 143, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.L.; Ma, L.; Mulley, C. The objective and perceived built environment: What matters for happiness? Cities Health 2017, 1, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S.; Lee, J.S. Meso- or micro-scale? Environmental factors influencing pedestrian satisfaction. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 30, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; McCormack, G.R.; Nakaya, T.; Shibata, A.; Ishii, K.; Yasunaga, A.; Hanibuchi, T.; Oka, K. Urban design and Japanese older adults’ depressive symptoms. Cities 2019, 87, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Pickett, A.C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S. Neighborhood physical environments, recreational wellbeing, and psychological health. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamour, Q.; Morelli, A.M.; Marins, K.R.D.C. Improving walkability in a TOD context: Spatial strategies that enhance walking in the Belém neighbourhood, in São Paulo, Brazil. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2019, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, S.T.; Larranaga, A.M.; Ochoa, J.A.A.; Samios, A.A.B.; Cybis, H.B.B. The role of security and walkability in subjective wellbeing: A multigroup analysis among different age cohorts. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Kent, J.L.; Mulley, C. Transport disadvantage, social exclusion, and subjective well-being. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D.; Gutscher, H.; Bauer, N. Walking in “wild” and “tended” urban forests: The impact on psychological well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, M.; Spray, J.; Wiles, J.; Anderson, A.; Willing, E.; Witten, K.; ‘Ofanoa, M.; Ameratunga, S. Locating transport sector responsibilities for the wellbeing of mobility-challenged people in Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Built environment and social well-being: How does urban form affect social life and personal relationships? Cities 2018, 74, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D.; Bhaduri, E.; Kumar, G.P.; Goswami, A.K. Assessment of relationships between user satisfaction, physical environment, and user behaviour in pedestrian infrastructure. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 2343–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Al-Hagla, K.; Hasan, A.E. The impact of attributes of waterfront accessibility on human well-being: Alexandria Governorate as a case study. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M.; Heijnen, M.; McKay, H.A. “Benches become like porches”: Built and social environment influences on older adults’ experiences of mobility and well-being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, D.; Okyere, S.A.; Nieto, M.; Kita, M.; Kusi, L.F.; Yusuf, Y.; Koroma, B. Walking off the beaten path: Everyday walking environment and practices in informal settlements in Freetown. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.-J.; Furuya, K.; Kasetani, T.; Takayama, N.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Relationship between psychological responses and physical environments in forest settings. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 102, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Walford, N.; Hockey, A.; Foreman, N.; Lewis, M. Older people and outdoor environments: Pedestrian anxieties and barriers in the use of familiar and unfamiliar spaces. Geoforum 2013, 47, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, V.C.; Manjourides, J.; Suh, H.H. Close proximity to roadway and urbanicity associated with mental ill-health in older adults. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.; Limb, E.S.; Shankar, A.; Nightingale, C.M.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Cummins, S.; Clary, C.; Lewis, D.; Cooper, A.R.; Page, A.S.; et al. Evaluating the effect of change in the built environment on mental health and subjective well-being: A natural experiment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Mondschein, A.; Neale, C.; Barnes, L.; Boukhechba, M.; Lopez, S. The Urban Built Environment, Walking and Mental Health Outcomes among Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 575946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, K.; Giusti, M.; Peterson, G.D.; Legeby, A.; Brandt, S.A.; Barthel, S. Impact of environment on people’s everyday experiences in Stockholm. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 171, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, C.; Gallacher, J.; Webster, C. Urban built environment configuration and psychological distress in older men: Results from the Caerphilly study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, R.; Cohen, D. Proximity to urban parks and mental health. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2014, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.H.; Lee, J.H. Residential environment, third places and well-being in Malaysian older adults. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 162, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Y.M.; Chui, C.H.K.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Chiu, R.L.H.; Kwok, R.; Tse, M.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Chau, P.-H.; Lum, T.Y.S. The Contribution of Sense of Community to the Association Between Age-Friendly Built Environment and Health in a High-Density City: A Cross-Sectional Study of Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Hong Kong. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yang, J.; Chai, Y. The Anatomy of Health-Supportive Neighborhoods: A Multilevel Analysis of Built Environment, Perceived Disorder, Social Interaction and Mental Health in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Teychenne, M.; McNaughton, S.A.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Salmon, J. Relationship of the Perceived Social and Physical Environment with Mental Health-Related Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Mediating Effects of Physical Activity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoven, B.; Meijering, L. Mundane mobilities in later life—Exploring experiences of everyday trip-making by older adults in a Dutch urban neighbourhood. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 30, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J.; Hall, S.J.; Abbott, G.; Flowers, E.P.; Turner, A.I. Examination of the acute heart rate and salivary cortisol response to a single bout of walking in urban and green environments: A pilot study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, C.; Gascon, M.; Ranzani, O.; Márquez, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Arjona, L.; Koch, S.; Llopis, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; et al. Physical and mental health effects of repeated short walks in a blue space environment: A randomised crossover study. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, S.; Heiler, A.; Pollmann, T.; Claßen, T.; Hornberg, C.; Kistemann, T. Do perceived walking distance to and use of urban blue spaces affect self-reported physical and mental health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjie, W.; Chen, Y.; Ye, L. Perceived spillover effects of club-based green space: Evidence from Beijing golf courses, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, K.; Macmillan, A.; Mackie, H.; van der Werf, B.; Smith, M.; Field, A.; Woodward, A.; Hosking, J. Te Ara Mua—Future Streets: Can a streetscape upgrade designed to increase active travel change residents’ perceptions of neighbourhood safety? Wellbeing Space Soc. 2022, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, W.Y.; Yun, Y.; Wang, F.; Gong, Z. Urban greenness, mixed land-use, and life satisfaction: Evidence from residential locations and workplace settings in Beijing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 224, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundling, C. Overall Accessibility of Public Transport for Older Adults. Doctoral Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. Available online: http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:898881/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Libardo, A.; Nocera, S. Exploring the perceived security in transit: The Venetian students’ perspective. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 2, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M. Neighbourhood design and fear of crime: A social-ecological examination of the correlates of residents’ fear in new suburban housing developments. Health Place 2010, 16, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, U.; Greve, W. The Psychology of Fear of Crime. Conceptual and Methodological Perspectives. Br. J. Criminol. 2003, 43, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijswijk, L.; Haans, A. Illuminating for Safety: Investigating the Role of Lighting Appraisals on the Perception of Safety in the Urban Environment. Environ. Behav. 2017, 50, 889–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys Smith, N. Heart in the Right Street. Beauty, Happiness and Health in Designing the Modern City; Create Street: Lambeth, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.A.; Huebner, B.M.; Bynum, T.S. Fear of crime and criminal victimization: Gender-based contrasts. J. Crim. Justice 2006, 34, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.Q.; Kelling, G.L. Broken Windows. 1982. Available online: www.theatlantic.com (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Jeffery, C.R. Crime Prevention through Urban Design, 2nd ed.; Sage Publishings: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention through Urban Design; Macmillan Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Ceccato, V. Is CPTED useful to guide the inventory of safety in parks? A study case in Stockholm, Sweden. Int. Crim. Justice Rev. 2016, 26, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J. Addressing the Security Needs of Women Passengers on Public Transport. Secur. J. 2008, 21, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, R. Designing urban space for psychological comfort: The Kentish Town Road project. J. Public Ment. Health 2005, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.L.; Julian, D.; Buchman, S.; Humphreys, D.; Mrohaly, M. The emotional quality of scenes and observation points: A look at prospect and refuge. Landsc. Plan. 1988, 10, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Herbert, E.J. Familiarity and Preference: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. In Environmental Aesthetics: Theories, Research and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Defined as adults in the study | Defined as children in the study. |

| Exposure | Association between (a) micro-scale urban outdoor environment, (b) pedestrian, and (c) psychological health. | Meso- and macro-scale environments. Lack of a, b, or c. Studies not focused on pedestrian actual behavior. Indoor environments. Rural study areas. “View from a window” studies, cyclability or other transport studies. |

| Outcome | Pedestrians’ psychological experience. | Physiological outcomes only. |

| Study design | All types of empirical study designs, quantitative and qualitative including actual pedestrians. Different objectives, variables, methods, settings, samples, and outcomes. Clearly stated research questions, methods, sample size, and results. | Prospective studies, reviews, reports, editorial, theoretical, and method-based articles. |

| Journal | No. of Publications |

|---|---|

| Landscape and Urban Planning | 8 |

| Urban Forestry & Urban Greening | 5 |

| Social Science & Medicine | 4 |

| Cities | 3 |

| Health & Place | 3 |

| Journal of Environmental Psychology | 3 |

| Research in Transportation Business & Management | 3 |

| Wellbeing, Space, and Society | 3 |

| Geoforum | 2 |

| Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health | 2 |

| Science of The Total Environment | 2 |

| Travel Behaviour and Society | 2 |

| Aging & Mental Health | 1 |

| Ain Shams Engineering Journal | 1 |

| Applied Research in Quality of Life | 1 |

| BMC Public Health | 1 |

| Case Studies on Transport Policy | 1 |

| Cities & Health | 1 |

| City, Culture, and Society | 1 |

| Environment and Behavior | 1 |

| Environmental Research | 1 |

| Frontiers in Public Health | 1 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 1 |

| International Journal of Sustainable Transportation | 1 |

| Journal of Applied Gerontology | 1 |

| The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics | 1 |

| Journal of Transport & Health | 1 |

| Journal of Transport and Land Use | 1 |

| Journal of Urban Design | 1 |

| PLOS ONE | 1 |

| Progress in Planning | 1 |

| Social Indicators Research | 1 |

| Transportation Research Part A | 1 |

| Transportation Research Part D | 1 |

| Transportation Research Procedia | 1 |

| Publications total | 63 |

| No. of Publications | |

|---|---|

| United States | 13 |

| China | 8 |

| Australia | 7 |

| United Kingdom | 6 |

| Canada | 4 |

| Brazil | 3 |

| Japan | 3 |

| New Zealand | 3 |

| Sweden | 2 |

| Belgium | 1 |

| Chile | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Iran | 1 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| Sierra Leone | 1 |

| South Korea | 1 |

| Spain | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| Total | 63 |

| Author, Year | Region | Respondents | N | Respondent Data Collection Methods | Sampling Method | Respondent Data Analysis | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfonzo et al. (2008) [37] | USA, California | Parents of 3rd–5th grade students | 1297 | Survey | Purposive | Descriptive, multiple regression analysis | The amount of walking performed by adults in their neighborhood: the most important criteria in the physical environment, as influenced by safety levels relative to crime. Mixed-used sidewalks, public open spaces, and higher adult walking rates. More windows facing the street, more street lighting, and fewer abandoned buildings, graffiti, rundown buildings, vacant lots, and undesirable land uses have higher adult walking rates. |

| Ayala-Azc-árraga et al. (2019) [38] | Mexico, Mexico City | ≥18 years old | 338 | Survey (person to person) | Convenience | Chi-square test, canonical correlation analysis. | Well-being explained by trustworthy neighbors, trustworthy visitors, and park shared with well-known people. |

| Bahrainy and Khosravi (2013) [39] | Iran, Hashtgerd New Town | Residents | 384 | Survey | Random sampling in selected clusters | Multivariate linear regression | The environment influences female residents more than male residents. Safety is the most important factor for women; for men, distance to destinations. |

| Barr et al. (2021) [40] | United Kingdom, Exeter | Commuters | 96 | Workshops, semi-structured discussions | Not specified. From previous study | Thematic analysis | Shared spaces: sites of uncertainty and conflict between different users. |

| Bereitschaft (2019) [41] | United States, Omaha | Residents | 293 | Survey | Random | Correlation, spatial point pattern test | Hotspots of walkability and creativity frequently overlapped. |

| Biglieri and Dean (2021) [42] | Canada, Waterloo, Ontario | 57–81 years with dementia | 7 | Longitudinal. Go along interviews, travel diary | Not specified | Grounded theory approach, coding, peer checked. Travel diary. | Persons with dementia avoided noisy, smelly, fast-moving arterial roads, and selected instead quieter residential or mixed-use streets, even if it took longer. It was difficult for persons with dementia when the neighborhood was lacking amenities within walking distance. |

| Bornioli et al. (2019) [43] | United Kingdom, Bristol | Adults working or studying | 398 | Experiment, photo-elicited semi-structured interviews | Convenience | Multiple regression | Safety, comfort, and moderate sensory stimulation are crucial elements for the walking experience. |

| Brancato et al. (2022) [44] | United States | 21–72 years old | 202 | Experiment (virtual walk) | Convenience (crowd- sourcing) | ANOVA | Pine forest walks were superior in inducing happiness in comparison with urban walks. Farm field walks were less fascinating than all other walks, including urban. Busy city center walks reduced feelings of calmness in comparison to all other walks. |

| Brown et al. (2007) [45] | United States, Salt Lake City | Students, trained raters | 73 + 4. | Experiment | Convenience | Environmental audit, Cohen’s kappa, PCA, coefficient alpha | An area where it is possible to watch people enjoying themselves gives a positive experience. Poor aesthetics interfere with a positive walking experience (e.g., dirty spaces, dark colors, abandoned buildings, litter, graffiti). Artistry and attractiveness of shop or store windows positively experienced. Shade gives a positive walking experience. |

| Bustamante et al. (2022) [46] | United States, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico | ≥55 years | 6938 | Questionnaire | Purposive convenience sampling | Thematic analysis, generalized linear models, chi-square | Depression and anxiety are inversely associated with the number of neighborhood parks. |

| Cambra and Moura (2020) [47] | Portugal, Lisbon | Individuals who lived in, worked in, or visited the area | 802 | Quasi-experiment, longitudinal survey | Not specified | T-tests | Walking experience related to sidewalk pavement quality, kiosks providing outdoor sitting places with extended working hours. Turning radius reduced to slow down turning traffic; crossing refuges enlarged. |

| Cao (2016) [48] | United States, Minneapolis, St Paul | Residents | 1303 | Survey | Stratified, random | SEM, confirmatory factor analysis | High density and poor street connectivity are detrimental to life satisfaction, but street connectivity is more influential than density. |

| Chan et al. (2018) [49] | China, Hong Kong | Urban park managers, local scholars, and local park users | 772 | Interviews and questionnaire | Stratified random | PCA, Crohnbach’s alpha | Safety and security are among the most important areas for management in parks. Natural settings such as ponds and trees are important for a pleasant feeling in parks. Soft landscape or green areas were preferred to hardware over built facilities. |

| Chan et al. (2021) [50] | China, Shenzhen | Residents | 20 | Walk-along and sedentary interviews | Purposive | Thematic analysis | Temporalities important for how a phenomenon is perceived, for example, in relation to safety. |

| Deng et al. (2020) [51] | China, Chengdu | Students | 60 | Questionnaires; Various physiological indicators | Convenience (randomization to conditions) | T-test, ANOVA. Wilcoxon signed-rank, Kruskal– Wallis. | Topography landscapes with natural mountain forest appear most restorative. Water, topography, and plants had positive restorative effects, as did bamboo forests, poetry walls, and decorative openwork windows. |

| Domènech-Abella et al. (2021) [52] | Belgium, Flandres | ≥60 years | 869 | Face-to-face questionnaire (interviews) | Not specified. Subsample from previous study. | Linear regression | No significant associations between traffic density and basic service availability and mental health. |

| Dzyuban et al. (2022) [53] | United States, Phoenix, Arizona | Residents | 14 | Survey: Thermal comfort (microclimate), pleasure, and visual experience during thermal walk. GPS. | Convenience | Descriptive statistics, Spearman correlation | Changes in pleasure resulting from slight changes in microclimate conditions in streets where participants walked. Participants could sense minor changes in microclimate and perceived shade as pleasant while walking down a street. |

| Finlay (2018) [54] | United States, Minneapolis | Residents, 55–92 years old | 125 | Interviews, observation | Purposive | Thematic analysis | Snow impacted participants; for example, they expressed anxiety because of fear of slipping on ice or were afraid of getting stuck. |

| Finlay et al. (2015) [55] | Canada, Vancouver | Older adults | 46 | Sit-down interviews, walking interview | Not specified. Partly based on earlier study. | Thematic analysis | Green and blue spaces impact mental health in later life. The spaces promote mental well-being and induce feelings of renewal, restoration, and spiritual connectedness, and support social engagement. |

| Fleming et al. (2016) [56] | New Zealand, whole country | ≥15 years | 22,727 | Survey | Random | Logit model estimated by maximum likelihood estimation. | When residents report that they feel unsafe in their neighborhood, psychological benefits of access to green space disappear almost entirely. |

| Foster et al. (2013) [57] | Australia, Perth | Residents (before and after relocation) | 1159 | Questionnaire (longitudinal) | Purposive (all who completed question aire from earlier study) | Linear regression | Shopping/retail land use enhances walking and paradoxically also possibly deteriorates walking by increased residents’ perceived crime risk. |

| Foster et al. (2015) [58] | Australia, Perth | Parents | 1245 | Cross-sectional study | Random, stratified | Descriptive | Neighborhood features minimizing vehicle traffic and encouraging pedestrians supported most parents’ perceptions of safe neighborhoods, regardless of socioeconomic status. |

| Francis et al. (2012) [59] | Australia, Perth | Residents building homes in new housing developments. | 911 | Survey | Not specified | Logistic regression | Odds for low psychosocial distress are higher for residents in neighborhoods with high-quality public open space (POS). POS attributes included walking paths, shade, water features, irrigated lawn, birdlife, lighting, sporting facilities, playgrounds, type of surrounding roads, and presence of nearby water. Quantity of POS has less mental health impact than quality. |

| Galea et al. (2005) [60] | United States, New York City | Residents ≥18 years old | 1355 | Telephone survey | Random | Cronbach’s alpha, multilevel hierarchical models, odds ratios | No impact on depression based on percentage of clean streets or sidewalks. A higher percentage of houses in deteriorating condition was associated with a greater likelihood of depression. |

| Gidlöf-Gunnarsson and Öhrström (2007) [61] | Sweden, Stock- holm, Gothen- burg | Residents exposed to high road traffic noise | 500 | Cross-sectional questionnaire | Not specified. Subsample from previous study | MANOVA, ANOVA, chi-square, t-tests, correlation | Better availability of nearby green areas important for well-being by reducing long-term noise annoyances and prevalence of stress-related psychosocial symptoms. |

| Guo et al. (2021) [62] | China, Hong Kong | Older adults | 1553 | Survey | Quota with stratification | SEM | Park green space positively affects mental health and subjective well-being. Vegetation-based green space negatively associated with subjective well-being. Density enhances subjective well-being in older adults. Perceived built environment and sense of community could fully explain the residential density and subjective well-being relationship. Street connectivity associated with mental health; however, inverted U-shape. |

| Herrmann-Lunecke et al. (2021) [63] | Chile, Santiago | Residents | 120 | In-depth walking interviews | Convenience | Grounded theory | The presence of trees, wide sidewalks and active uses of design features ease walking, elicit well-being and happiness. Traffic noise, motorized traffic, narrow and deteriorated sidewalks, and difficult crossings hinder walking, especially for older adults and women, causing stress, fear, and anger. |

| Høj et al. (2021) [64] | Canada, Montreal | Residents | 929 | Face-to-face questionnaire, longitudinal | Stratified | Linear growth mixture- modeling | Public open space (POS) per se did not attenuate impact of stressful events on psychological distress or independently protect against psychological distress but “greener” POS protected against rising stress in both cases. |

| Juntti and Lundy (2017) [65] | United Kingdom, London | Lived in local social housing or had worked there for over one year | 10 | Interview, visual and textual recording | Convenience | Constructivist approach, descriptive | Parks give a positive sense, for example, if offering an activity such as a basketball court, jogging, or festivals. Even small pocket green spaces are positive. Benches portrayed as enabling factors for giving positive experience. |

| Juntti et al. (2021) [66] | Brazil, Belo Horizonte | Residents | 24 | In-depth interviews, accompanied walks, “walking narrative” | Purposive | Cross-referencing, thematic analysis | Well-being is only experienced when residents feel safe in their neighborhood. |

| Kent et al. (2017) [67] | Australia, Sydney | Households | 562 | Survey | Not specified | PCA, correlation, ordered logit model, Tobit model | Aesthetics associated with subjective well-being. Aesthetics here are defined as presence of street trees and views, and evaluation of the attractiveness of buildings. |

| Kim et al. (2014) [68] | South Korea, Seoul | Pedestrians | 28,000 | Survey | Convenience | Descriptive statistics, correlations, multilevel modeling, ordinal logit, likelihood ratio | Trees associated with satisfaction, as were bus lanes, width of sidewalks, crossing signs, traffic lights, pedestrian crossings, and availability of bus stops. Intersection density had a negative effect on satisfaction as did hilly topography. |

| Koohsari et al. (2019) [69] | Japan, Matsudo City | Residents aged 65–84 years old | 328 | Questionnaire, on-sight health examination | Random | Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlations, Gender- stratified multivariable linear and binary logistic regression, Odd ratios (OR) | Walkable environment characterized by high population density and proximity to local destinations is supportive of better mental health among older adults, in particular women. |

| Kwon et al. (2019) [70] | United States, Texas/Ohio | Residents | 1392 | Survey | Convenience (crowd-sourcing) | SEM | Safety from crime not related to recreational well-being. |

| Lamour et al. (2019) [71] | Brazil, São Paulo | Pedestrians | 79 | Observation, survey/street/ interview | Purposive/ convenience | Not specified | Attributes related to safety and security are important (good crossing conditions, good pedestrian signage, pavement quality, secure speed limit, presence of traffic lights, street lighting, security from crime, pedestrians in the same area). |

| Lucchesi et al. (2021) [72] | Brazil, Sao Paolo | Young adults (18 to 29 years old), middle-aged adults-1 (30 to 45), middle- aged adults-2 (46 to 59) and older adults (60 to 70 years old) | 2300 | Interviews | Probabilistic, stratified | SEM, configural model, chi-square | Subjective well-being positively influenced by security in all age cohorts. Safety had the highest effect on the elderly while middle-aged people valued walkability. Younger people seemed to be least influenced by safety and walkability. |

| Ma et al. (2018) [73] | Australia, Sydney | Residents | 562 | Survey | Purpose, representative | Descriptive, SEM | Cohesive neighborhood environment associated with better mental health, better subjective well-being. The aesthetics and the social environment of the neighborhood had the strongest effects on subjective well-being. |

| Martens et al. (2011) [74] | Switzer- land, Zurich | General public | 96 | Experiment (questionnaire) | Convenience, then randomly assigned | Factor analysis, Cronbach’s alpha, ANOVA | Participants who walked in a tended forest had a stronger increase in positive affect and a stronger decrease in negative affect than those who walked in a wild forest. |

| Meher et al. (2021) [75] | New Zealand, Aotearoa, Auckland | Older or mobility- impaired people | 62 | Interviews | Purposive | Thematic | Absence of concrete sidewalks, cracks in the pavement, obstructions to public footpaths, barriers related to safety as well as overhanging tree branches and cars parked in driveways. Beautiful sights increase well-being (e.g., trees, sky, birds, and sea). |

| Mouratidis (2018) [76] | Norway, Oslo | ≥18 years | 1344 | Survey, in-depth interview. | Random | SEM | Compactness positive for the number of close relationships, frequency of meeting friends and relatives, social support, opportunities to meet new people, and satisfaction with personal relationships. |

| Nag et al. (2020) [77] | India, Kolkata | Users | 400 | Surveys | Not specified | Ordered logistic regression and odds ratio analysis. Negative binomial regression | Obstructions along footpaths have negative impact on satisfaction. Important also: barrier between footpath and road, zebra crossings, footpath continuity, and lights. |

| Othman et al. (2021) [78] | Egypt, Alexandria | Responses from Smouha and the Northern Zone | 202 | Survey | Random sample and convenience | Descriptive, regression, chi-square, Mann–Whitney Test, t-test | Street linearity contributes to satisfaction, as do perpendicularity and ease of wayfinding, hierarchy of streets, continuity, connectivity, width of sidewalks, crossing signs, and traffic lights. |

| Ottoni et al. (2016) [79] | Canada, Vancou- ver | 61–89 years | 50 | Semi-structured interviews | Purposive | Thematic review | For older adults, benches positively contributed to their mobility experiences by enhancing both use and enjoyment of green and blue spaces, serving as a mobility aid. |

| Oviedo et al. (2021) [80] | Sierra Leone, Freetown | Residents of Moyiba | 38 | Structured interview/questionnaire | Convenience | Descriptive | Positive for walking experience: lack of traffic, longer distance to major roads, diversity of street activities, shade, and vistas. Functioning streetlights along the footpath are important for positive walking experience and satisfaction. Benches are enabling or give a positive experience. Unpaved or damaged routes mean lower comfort. Dust or dirt, street isolation, and lack of trees are negative for the walking experience. |

| Park et al. (2011) [81] | Japan | Male university students with no reported history of physical or psychiatric disorders. | 168 | Field experiments (questionnaire, walk) | Not specified | The Steel–Dwass test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, PCA | Forest setting compared to urban setting is more enjoyable, friendly, natural, and sacred. Psychological response is also related to air temperature, relative humidity, radiant heat, and wind velocity. |

| Phillips et al. (2013) [82] | United Kingdom, Swansea | Older adults | 44 | Interviews, images, “field” visit, focus group | Purposive convenience | Cronbach alpha, PCA, content analysis | Barriers for older people in new environments include poor signage, confusing spaces, poor paving, and ‘sensory overload’, i.e., noise and complexity of the environment. Landmarks and distinctive buildings are more important than signage in navigating unfamiliar areas. |

| Pun et al. (2019) [83] | United States, whole country | 57–85 years. | 4750 | Questionnaire | Not specified | Linear mixed models | Increase in roadway distance significantly associated with decrease in depressive score both directly and through loneliness. |

| Ram et al. (2020) [84] | United Kingdom, London East Village | Adults seeking different housing tenures | 1278 | Controlled prospective cohort study | Purposive | Multilevel linear regression | Closer to the nearest park, more walkable areas, better access to public transport, and measured improvements in neighborhood perceptions gave no evidence of improved mental health and well-being. |

| Roe et al. (2020) [85] | United States, Virginia, Rich- mond | Residents from an independent living facility for older people | 11 | Repeated measures, cross-over design, experiment | Purposive | T-test, descriptive analysis, multilevel random coefficient modeling | Significant positive health benefits from walking in the urban green district on emotional well-being (happiness levels) and stress physiology. |

| Samuelsson et al. (2018) [86] | Sweden, Stock- holm | General public | 1032 | Survey | Convenience | Logistic regression | Areas with proximity to major roads associated with negative experiences. There was a decline in probability of positive experiences for the first 300 m. for natural environments, while it increased after that. Natural shading by trees strongly predicted positive experiences. |

| Sarkar et al. (2013) [87] | United Kingdom, Wales, Caer philly | Men 65–84 years | 687 | Questionnaire, clinical examinations | Not specified. Based on previous study | Logistic regression | Higher degree of land-use mix associated with lower psychological distress. Diversity and many simultaneous impressions are not always positive. People living in terraced houses have reduced psychological distress compared to those living in detached houses. In hilly environments—when the variability in slope is higher, increased risk of psychological distress. |

| Sturm and Cohen (2014) [88] | United States, Los Angeles | Residents | 1070 | Survey | Stratified | Multiple regression | Residents within a short walking distance from parks (400 m) have mental health benefits, with a significant decrease over the next distance values. |

| Tan and Lee (2022) [89] | Malaysia, Bandar Sunway | Residents 60 years and older | 250 | Survey, in-depth interview | Purposive | Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) | Life satisfaction is not well-related to walkability, pedestrian accessibility, and maintenance of the neighborhood. |

| Tang et al. (2021) [90] | China, Hong Kong | Residents, middle-aged and older adults | 2247 | Face-to-face interviews | Quota with stratification | Pearson correlation | Cleanliness and green spaces are associated with better mental health in older people, as are pavements, barriers between footpaths and road, zebra crossings, footpath continuity, and lights. |

| Tao et al. (2020) [91] | China/Beijing | Residents 18–65 | 1256 | Survey | Stratified random | SEM | Proximity to parks as the sole indicator directly linked to mental health. |

| Van Dyck et al. (2015) [92] | Australia, Victoria | 55–65 years | 3965 | Surveys | Not specified. Baseline data from previous study. | Descriptive, Pearson correlations, g multiple linear mixed models, mediation analyses | Areas pleasant to walk, those with tree shade, easy-to-walk places, and often seeing others walking supported walking, which mediated mental-health-related quality of life. |

| van Hoven and Meijering (2019) [93] | Netherlands, Groning- en | Older adults | 7 | Interviews, neighborhood walks | Convenience | Thematic analysis | For older adults, cobblestone can induce fear of lack of control. Trees can provide sun and shade making walking there pleasant. Many of the benign variables are weather-dependent. |

| Veitch et al. (2022) [94] | Australia, Melbourne | Participants recruited at university | 20 | Experimental | Oppor tunistic | ANOVA | Urban walking in comparison with green walking conditions: no statistically significant differences in changes in heart rate or cortisol in response to walking. |

| Vert et al. (2020) [95] | Spain, Barcelona | Adult office workers | 59 | Randomized crossover design | Random | Mixed-effects regression | Well-being and mood response significantly improved after subjects had been walking in blue space in comparison with resting in the control site or after walking in urban space. |

| Völker et al. (2018) [96] | Germany, Bielefeld, Gelsenkirchen | Residents | 1041 | Questionnaires. | Random | Descriptive and bivariate analysis, linear multiple regression | Blue space use increases the probability of being healthier in highly urbanized areas. |

| Wenjie et al. (2020) [97] | China, Beijing | Residents | 4762 | Questionnaire | Stratified | Multilevel-ordered logistic regression | Positive association between residential proximity to golf courses and life satisfaction. This association is more pronounced for residents living at the closest distance and, for example, golf landscape characteristics. |

| Witten et al. (2022) [98] | New Zealand/Aotearoa, Auckland, Mangere | Adults, children. Residents, local stakeholders. | Data collec tion 1: 1234 + 658. Data collec tion 2: 1275 + 628. | Longitudinal face-to-face survey, focus groups, go-along interviews | Random | General linear mixed modeling, thematic analysis | Results support the importance of combining traffic and personal safety as well as multiple measures when investigating pathways between active travel and the built environment. |

| Wu et al. (2022) [99] | China, Beijing | Residents | 3495 | Survey, face-to-face interviews | Stratified | Descriptive statistics, Bayesian multilevel ordered logit modeling | Mixed land use (residential, commercial, and public services) positive for life satisfaction in both residential and workplace settings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sundling, C.; Jakobsson, M. How Do Urban Walking Environments Impact Pedestrians’ Experience and Psychological Health? A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410817

Sundling C, Jakobsson M. How Do Urban Walking Environments Impact Pedestrians’ Experience and Psychological Health? A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410817

Chicago/Turabian StyleSundling, Catherine, and Marianne Jakobsson. 2023. "How Do Urban Walking Environments Impact Pedestrians’ Experience and Psychological Health? A Systematic Review" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410817

APA StyleSundling, C., & Jakobsson, M. (2023). How Do Urban Walking Environments Impact Pedestrians’ Experience and Psychological Health? A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(14), 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410817