Rural-Urban Linkages: Regional Financial Business Services’ Integration into Chilean Agri-Food Value Chains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Dimensions of Regional Disparities in Finance and Agriculture

2.1. The Geography of Financial Business Services

2.2. Agri-Food Value Chain and the Financial-Growth Nexus

3. Methodology

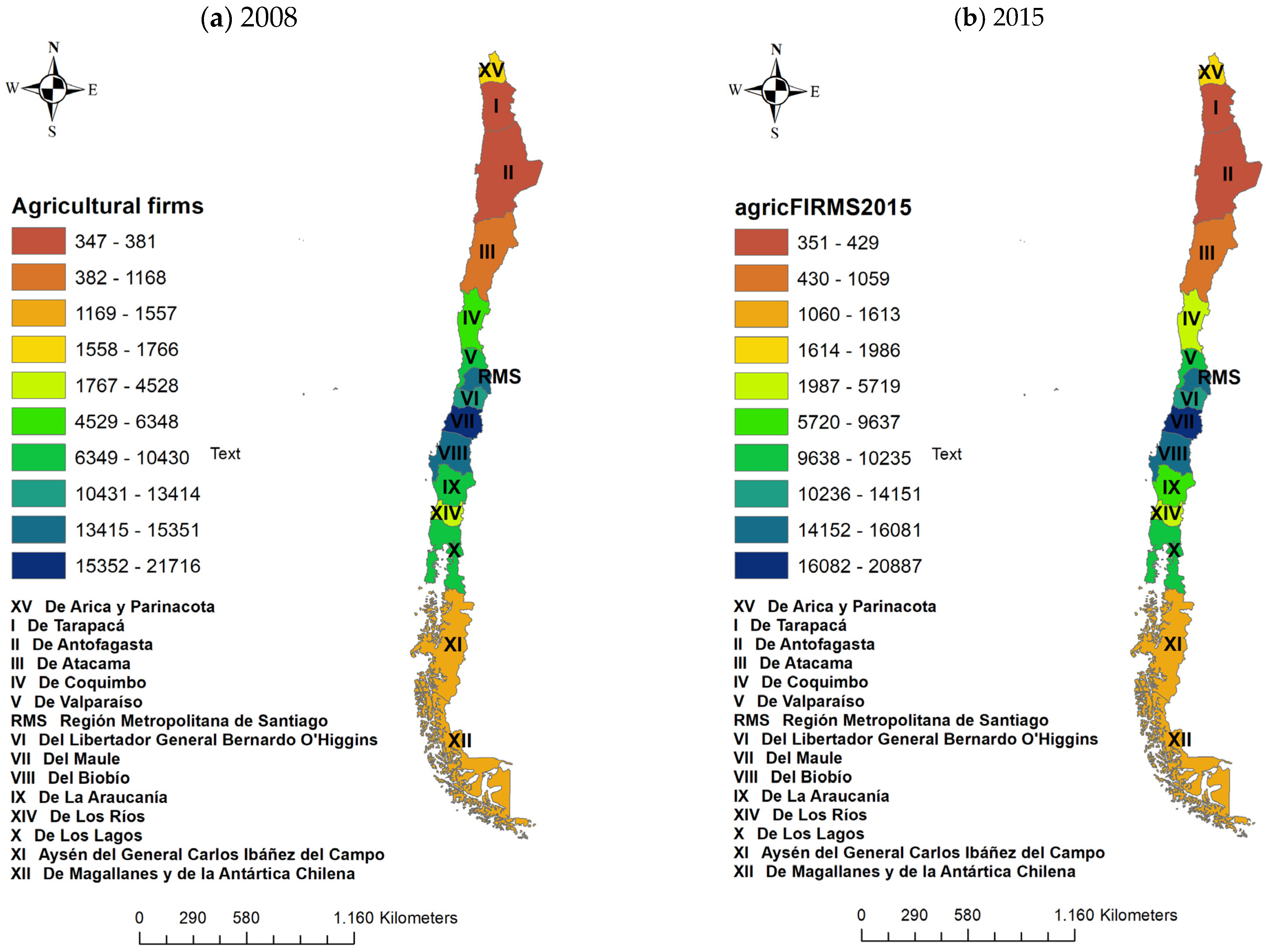

Data

4. Results

4.1. TiVA to DVC and GVC

4.2. TiVA for Agri-Food-Related Industries

4.3. Financial Business Services into Agri-Food Trade

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Los, B.; Timmer, M.P.; de Vries, G.J. How global are global value chains? A new approach to measure international fragmentation. J. Reg. Sci. 2015, 55, 66–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Luca, D. The big-city bias in access to finance: Evidence from firm perceptions in almost 100 countries. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Zambrano, J.; Ramírez-Gil, J.G.; Barrios, D. Validating Technologies and Evaluating the Technological Level in Avocado Production Systems: A Value Chain Approach. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Z.; Joshi, P.K.; Cheng, E.; Birthal, P.S. Innovations in financing of agri-food value chains in China and India Lessons and policies for inclusive financing. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2015, 7, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, K.; Lahiani, A.; Roubaud, D. Natural resources as blessings and finance-growth nexus: A bootstrap ARDL approach in an emerging economy. Resour. Policy 2019, 60, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droguett, S.E. Financial Inclusion and Small Businesses Growth. Master’s Thesis, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, T.; Winkler, A. The challenge of rural financial inclusion—Evidence from microfinance. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 1555–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, M.P.; Miroudot, S.; De Vries, G.J. Functional specialisation in trade. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehta, B.S. Inter-industry Linkages of ICT Sector in India. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 2020, 14, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, P.H.; Francois, J.; Nelson, D.R. The Role of Goods-Trade Networks for Services-Trade Volume. World Econ. 2017, 40, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, J.; Manchin, M.; Tomberger, P. Services Linkages and the Value Added Content of Trade. World Econ. 2015, 38, 1631–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, R.C.; Noguera, G. Accounting for intermediates: Production sharing and trade in value added. J. Int. Econ. 2012, 86, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koopman, R.; Wang, Z.; Wei, S.-J. Tracing Value-Added and Double Counting in Gross Exports. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 459–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borsellino, V.; Schimmenti, E.; El Bilali, H. Agri-Food Markets towards Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Polit. Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.A.; Araújo, I.F. The internal geography of services value-added in exports: A Latin American perspective. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2021, 100, 713–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D.A.; Abler, D.G. Does agricultural trade affect productivity? Evidence from Chilean farms. Food Policy 2013, 41, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimón, J.; Chaminade, C.; Maggi, C.; Salazar-Elena, J.C. Policies to Attract R&D-related FDI in Small Emerging Countries: Aligning Incentives with Local Linkages and Absorptive Capacities in Chile. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaitán-Cremaschi, D.; Klerkx, L.; Duncan, J.; Trienekens, J.H.; Huenchuleo, C.; Dogliotti, S.; Contesse, M.E.; Rossing, W.A.H. Characterizing diversity of food systems in view of sustainability transitions. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanter, D.R.; Musumba, M.; Wood, S.L.R.; Palm, C.; Antle, J.; Balvanera, P.; Dale, V.H.; Havlik, P.; Kline, K.L.; Scholes, R.J.; et al. Evaluating agricultural trade-offs in the age of sustainable development. Agric. Syst. 2016, 163, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, J.; Cabral, S. Vertical specialization across the world: A relative measure. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2009, 20, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Lakner, Z. Food Supply Chain and Business Model Innovation. Foods 2020, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cruz-García, P.; Macedo, M.D.C.D.P.; Tortosa-Ausina, E. Financial inclusion and exclusion across Mexican municipalities. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2021, 13, 1496–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievoli, C.; Belliggiano, A.; Marandola, D.; Pistacchio, G.; Romagnoli, L. Network Contracts in the Italian agri-food industry: Determinants and spatial patterns. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2019, 275–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.H.; Azman-Saini, W.; Ibrahim, M.H. Institutional quality thresholds and the finance—Growth nexus. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 5373–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.; Imori, D.; Ferreira, J.-P.; Guilhoto, J.J.M.; Barata, E.; Ramos, P. Energy–Economy–Environment Interactions: A Comparative Analysis of Lisbon and Sao Paulo Metropolitan Areas. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2019, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reaz; Bowyer, D.; Vitale, C.; Mahi, M.; Dahir, A.M. The nexus of agricultural exports and performance in Malaysia: A dynamic panel data approach. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, M.; Nchake, M. Impact of credit market conditions on agriculture productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2021, 81, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, N.; Osabuohien, E.; Asongu, S. Agro-industrialisation and financial intermediation in Nigeria. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2020, 11, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.U. Access to Finance: An Empirical Analysis. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2014, 26, 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breitenlechner, M.; Gächter, M.; Sindermann, F. The finance–growth nexus in crisis. Econ. Lett. 2015, 132, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Venables, A.J. Spiders and snakes: Offshoring and agglomeration in the global economy. J. Int. Econ. 2013, 90, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Fang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y. Measuring China’s domestic production networks through Trade in Value-added perspectives. Econ. Syst. Res. 2017, 29, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, D.; Martin, A.; Adriaens, P. Applied Financial Metrics to Measure Interdependencies in a Waterway Infrastructure System. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2021, 27, 05020010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I.; Dietzenbacher, H.; Hewings, G.J. Fragmentation and Complexity: Analyzing Structural Change in the Chicago Regional Economy. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2009, 23, 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, E.A.; de Araújo, I.F.; de Almeida Vale, V.; Sandoval, H.D.; Roman, P.A.G.; Rodríguez, L.A.C.; Jaramillo, E.A.; Lopez, L.J.G. Dimensions of local development in the Colombian Pacific Region. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2021, 13, 1348–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, A.; Fricke, S. Sectoral linkages of financial services as channels of economic development—An input–output analysis of the Nigerian and Kenyan economies. Rev. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehigiamusoe, K.U.; Samsurijan, M.S. What matters for finance-growth nexus? A critical survey of macroeconomic stability, institutions, financial and economic development. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 26, 5302–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, R.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Makino, S.; Qian, G.; Boschma, R. Zoom in, zoom out: Geographic scale and multinational activity. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Cullinane, K. Finance and Risk Management for International Logistics and the Supply Chain; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Transmission of Domestic and External Shocks through Input-Output Network: Evidence from Korean Industries. IMF Work. Pap. 2019, 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, G.L. Learning-by-doing and knowledge management in financial markets. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luck, P. Global supply chains, firm scope and vertical integration: Evidence from China. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 19, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Roura, J.R. Service Industries and Regions. In Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; p. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthi, S.; Thierstein, A.; Bentlage, M. The Relational Geography of the Knowledge Economy in Germany: On Functional Urban Hierarchies and Localised Value Chain Systems. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialization, Regional Growth and Applications to European Union Cohesion Policy. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt, A.; Low, S.; Jablonski, B.B.; Weiler, S. Place-Based Factors and the Performance of Farm-Level Entrepreneurship: A Spatial Interaction Model of Agritourism in the U.S. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2019, 49, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, T.P.T.; Ordóñez, J.A. Agglomeration economies and urban productivity. Region 2019, 6, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Narula, R. An extended dual economy model: Implications for emerging economies and their multinational firms. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 13, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancati, E.; Brancati, R.; Maresca, A. Global value chains, innovation and performance: Firm-level evidence from the Great Recession. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 1039–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, P.J. Managing Agricultural Value Chains in a Rapidly Urbanizing World. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrey, S.H.; Bhat, S.A. Individual risk propensity and agri-entrepreneurial financing effectiveness: Strategy for sustainable agri-financing. Decision 2019, 46, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, V.; Dharani, M. Analyzing the agricultural value chain financing: Approaches and tools in India. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2016, 76, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guevara, J.F.; Maudos, J. Regional Financial Development and Bank Competition: Effects on Firms’ Growth. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, N.; Brown, R. Innovation, SMEs and the liability of distance: The demand and supply of bank funding in UK peripheral regions. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 233–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyiriuba, L.; Okoro, E.O.; Ibe, G.I. Strategic government policies on agricultural financing in African emerging markets. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2020, 80, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porgo, M.; Kuwornu, J.K.; Zahonogo, P.; Jatoe, J.B.D.; Egyir, I.S. Credit constraints and labour allocation decisions in rural Burkina Faso. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletschner, D.; Guirkinger, C.; Boucher, S. Risk, Credit Constraints and Financial Efficiency in Peruvian Agriculture. J. Dev. Stud. 2010, 46, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-J. Research on Investment Risk Influence Factors of Prefabricated Building Projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 26, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoruk, D.E. Dynamics of firm-level upgrading and the role of learning in networks in emerging markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 145, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, A.L.; Maggioni, D.; Zazzaro, A. Financial dependence and growth: The role of input-output linkages. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 162, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gereffi, G. Global value chains and international development policy: Bringing firms, networks and policy-engaged scholarship back in. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2019, 2, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, S.; Gereffi, G.; Raj-Reichert, G.; Gereffi, G. Economic upgrading in global value chains. Handb. Glob. Value Chain. 2019, 240, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Liu, C.-F.; Lin, Y.-T.; Yain, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-H. New agriculture business model in Taiwan. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trienekens, J.; van Velzen, M.; Lees, N.; Saunders, C.; Pascucci, S. Governance of market-oriented fresh food value chains: Export chains from New Zealand. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Anthopoulou, T.; Dahlström, K.; Tunón, H. Determinants and Mechanisms of Digital Financial Inclusion Development: Based on Urban-Rural Differences. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.C.; Taylor, P.J. ‘Gateway Cities’ in Economic Globalisation: How Banks Are Using Brazilian Cities. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. en Soc. Geogr. 2006, 97, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Jones-Evans, D. SMEs, banks and the spatial differentiation of access to finance. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, A.; Borisov, A.; Zazzaro, A. Do banks price discriminate spatially? Evidence from small business lending in local credit markets. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 4183–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenzen, M.; Benrimoj, C.; Kotic, B. Input-output analysis for business planning: A case study of the university of Sydney. Econ. Syst. Res. 2010, 22, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Torero, M.; Donovan, J.; Horton, D. Agricultural innovation and inclusive value-chain development: A review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atienza, M.; Arias-Loyola, M.; Phelps, N. Gateways or backdoors to development? Filtering mechanisms and territorial embeddedness in the Chilean copper GPN’s urban system. Growth Chang. 2019, 52, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Al-Maadeed, M. Agri-Food Markets in Qatar: Drivers, Trends, and Policy Responses. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroegindewey, R.; Hodbod, J. Resilience of Agricultural Value Chains in Developing Country Contexts: A Framework and Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.; Los, B.; McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R.; Thissen, M.; van Oort, F. The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of The Channel. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 97, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Los, B.; Timmer, M.P.; de Vries, G.J. Tracing Value-Added and Double Counting in Gross Exports: Comment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 1958–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atienza, M.; Aroca, P.; Stimson, R.; Stough, R. Are vertical linkages promoting the creation of a mining cluster in Chile? An analysis of the SMEs’ practices along the supply chain. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2016, 34, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariolis, T.; Veltsistas, P. Zero Measure Sraffian Economies: New Insights from Actual Input–Output Tables. Contrib. Politi- Econ. 2022, 41, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, J.; Cabral, S. Networks of Value-added Trade. World Econ. 2017, 40, 1291–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miroudot, S.; Ye, M. Multinational production in value-added terms. Econ. Syst. Res. 2019, 32, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzenbacher, E.; Lahr, M.L. EXPANDING EXTRACTIONS. Econ. Syst. Res. 2013, 25, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.A.; Perobelli, F.S.; Araújo, I.F.; Bugarin, K.S.S. Structural propagation of pandemic shocks: An input–output analysis of the economic costs of COVID-19. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2020, 16, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.A.; Mengoub, F.E.; Vale, V.A. Water content in trade: A regional analysis for Morocco. Econ. Syst. Res. 2020, 32, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Blair, P.D. Input-Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, A.; Jensen, J.B. The tradability of services: Geographic concentration and trade costs. J. Int. Econ. 2019, 118, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Abula, B.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Regional Business Environment, Agricultural Opening-Up and High-Quality Development: Dynamic Empirical Analysis from China’s Agriculture. Agronomy 2022, 12, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguinet, E.R.; Rodriguez-Puello, G. Tertiary industries’ value-added as a linkage’s engine: An interstate input-output application for Brazilian regions. Investig. Reg.-J. Reg. Res. 2022, 54, 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2008 | Share (%) | 2010 | Share (%) | 2012 | Share (%) | 2015 | Share (%) | Average Annual Variation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 722 | 0.8% | 795 | 0.8% | 928 | 0.8% | 1209 | 0.8% | 7.7% |

| R2 | 2762 | 3.2% | 3520 | 3.4% | 2873 | 2.4% | 3355 | 2.3% | 3.4% |

| R3 | 10,558 | 12.3% | 13,939 | 13.6% | 14,169 | 11.9% | 14,553 | 10% | 5.2% |

| R4 | 2207 | 2.6% | 3065 | 3% | 3567 | 3% | 3191 | 2.2% | 6.3% |

| R5 | 2650 | 3.1% | 3558 | 3.5% | 4049 | 3.4% | 4247 | 2.9% | 7.6% |

| R6 | 7388 | 8.6% | 9162 | 8.9% | 10,553 | 8.9% | 13,418 | 9.2% | 8.9% |

| R7 | 37,426 | 43.6% | 43,462 | 42.4% | 53,525 | 45.1% | 67,439 | 46.3% | 8.8% |

| R8 | 4286 | 5% | 5399 | 5.3% | 5889 | 5% | 7282 | 5% | 8% |

| R9 | 3257 | 3.8% | 3374 | 3.3% | 4091 | 3.4% | 5454 | 3.7% | 7.8% |

| R10 | 7178 | 8.4% | 7737 | 7.5% | 9270 | 7.8% | 12,164 | 8.4% | 7.9% |

| R11 | 2287 | 2.7% | 2683 | 2.6% | 3064 | 2.6% | 4005 | 2.8% | 8.4% |

| R12 | 1172 | 1.4% | 1399 | 1.4% | 1587 | 1.3% | 2135 | 1.5% | 9% |

| R13 | 2459 | 2.9% | 2804 | 2.7% | 3299 | 2.8% | 4811 | 3.3% | 10.3% |

| R14 | 452 | 0.5% | 567 | 0.6% | 607 | 0.5% | 751 | 0.5% | 8.3% |

| R15 | 1001 | 1.2% | 1148 | 1.1% | 1324 | 1.1% | 1550 | 1.1% | 0% |

| Total | 85,805 | 100% | 102,612 | 100% | 118,795 | 100% | 145,564 | 100% | 7.2% |

| Industry | OECD Industries | Outflow Type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agriculture | TTL_01T03: Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | Goods |

| 2 | Food related industry | TTL_10T12: Food products, beverages, and tobacco | Goods |

| 3 | Food services | TTL_55T56: Accommodation and food services | Services |

| 4 | Financial Business Services | TTL_62T63: IT and other information services | Services |

| TTL_64T66: Financial and insurance activities | |||

| TTL_68: Real estate activities | |||

| TTL_69T82: Other business sector services | |||

| Region | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | DVC | GVC | |

| R1 | 548 | 260 | 587 | 204 | 683 | 216 | 794 | 271 | 875 | 243 | 981 | 265 | 993 | 238 | 908 | 224 |

| R2 | 739 | 2845 | 733 | 2799 | 1071 | 3857 | 1136 | 3683 | 1107 | 2420 | 1163 | 2808 | 1056 | 2853 | 986 | 2111 |

| R3 | 1136 | 14,125 | 999 | 13,370 | 1901 | 19,296 | 2098 | 19,737 | 1862 | 19,471 | 1584 | 17,426 | 1593 | 16,624 | 1395 | 1367 |

| R4 | 863 | 2299 | 919 | 1989 | 1368 | 3088 | 1476 | 3824 | 1336 | 3198 | 1417 | 3125 | 1339 | 2615 | 1303 | 1882 |

| R5 | 939 | 1986 | 922 | 1757 | 1193 | 3160 | 1328 | 4144 | 1369 | 3777 | 1441 | 3232 | 1454 | 2938 | 1370 | 2187 |

| R6 | 824 | 4252 | 1094 | 3888 | 1722 | 4942 | 1879 | 5959 | 1944 | 5961 | 2386 | 5854 | 2037 | 5549 | 2106 | 4794 |

| R7 | 9005 | 14,396 | 9395 | 12,719 | 1168 | 15,690 | 14,133 | 18,464 | 16,839 | 18,867 | 18,429 | 19,586 | 17,600 | 18,434 | 16,253 | 15,872 |

| R8 | 1259 | 3398 | 1102 | 3350 | 1453 | 4490 | 1608 | 4892 | 1533 | 4706 | 1662 | 4507 | 1823 | 4483 | 1712 | 3857 |

| R9 | 1619 | 1307 | 1486 | 1055 | 1476 | 1168 | 1734 | 1388 | 1799 | 1337 | 1932 | 1349 | 2028 | 1350 | 1925 | 1453 |

| R10 | 1541 | 3294 | 1635 | 2693 | 1539 | 2897 | 1774 | 3582 | 2274 | 3276 | 2534 | 3377 | 2433 | 3592 | 2328 | 3322 |

| R11 | 788 | 854 | 841 | 674 | 967 | 810 | 1203 | 906 | 1464 | 831 | 1600 | 865 | 1541 | 817 | 1475 | 794 |

| R12 | 617 | 541 | 651 | 436 | 766 | 541 | 870 | 593 | 988 | 551 | 1093 | 589 | 1091 | 591 | 1057 | 552 |

| R13 | 824 | 1017 | 857 | 944 | 1097 | 1008 | 1242 | 1277 | 1388 | 1165 | 1562 | 1391 | 1592 | 1734 | 1385 | 1337 |

| R14 | 438 | 128 | 459 | 128 | 581 | 152 | 675 | 197 | 696 | 184 | 837 | 240 | 920 | 285 | 703 | 136 |

| R15 | 518 | 589 | 541 | 460 | 653 | 547 | 751 | 625 | 879 | 568 | 1018 | 584 | 989 | 607 | 926 | 359 |

| Chile | 21,658 | 51,291 | 22,223 | 46,466 | 27,541 | 61,863 | 32,702 | 69,542 | 36,354 | 66,555 | 39,641 | 65,198 | 38,487 | 62,713 | 35,833 | 51,947 |

| National composition | 30% | 70% | 32% | 68% | 31% | 69% | 32% | 68% | 35% | 65% | 38% | 62% | 38% | 62% | 41% | 59% |

| Region | 2008 | 2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGR | FOO | FOS | AGR | FOO | FOS | |

| R1 | 2.85 | −1.85 | −2.30 | 24.56 | −11.39 | −6.57 |

| R2 | −21.24 | −14.71 | −3.14 | −19.39 | −25.18 | −8.25 |

| R3 | −81.86 | −53.54 | −31.12 | −98.86 | −108.22 | −75.40 |

| R4 | 3.80 | −10.41 | −7.19 | 2.20 | −18.60 | −14.97 |

| R5 | 75.74 | −13.40 | −6.09 | 131.15 | −26.01 | −14.54 |

| R6 | −105.30 | −41.02 | −24.41 | −89.21 | 14.83 | −31.93 |

| R7 | −164.25 | 30.04 | 129.43 | −316.17 | 42.88 | 273.23 |

| R8 | 151.48 | 16.13 | −7.39 | 278.06 | 8.57 | −26.18 |

| R9 | 71.21 | 24.58 | −4.86 | 133.38 | 23.16 | −13.95 |

| R10 | −28.74 | 48.77 | −17.52 | −67.84 | 68.88 | −34.25 |

| R11 | 64.46 | 1.00 | −6.46 | 63.57 | −2.99 | −9.98 |

| R12 | −14.48 | 10.02 | −4.41 | −12.24 | 13.19 | −8.85 |

| R13 | 27.15 | 7.66 | −7.12 | −25.64 | 28.76 | −18.16 |

| R14 | 41.34 | −7.94 | −3.17 | 28.91 | −9.73 | −4.78 |

| R15 | −22.16 | 4.67 | −4.25 | −32.48 | 1.85 | −5.41 |

| Agriculture | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | DVC | GVC | Variation on Composition | |||||||||

| 2008 | (%) | 2015 | (%) | Relative Variation | 2008 | (%) | 2015 | (%) | Relative Variation | DVC | GVC | |

| R1 | 1.7 | 3% | 2.3 | 3% | −12% | 0.7 | 1% | 0.8 | 1% | −42% | 6% | −17% |

| R2 | 1.1 | 2% | 1.4 | 2% | −13% | 0.0 | 0% | 0.0 | 0% | −45% | 0% | −31% |

| R3 | 1.4 | 3% | 1.0 | 1% | −51% | 0.0 | 0% | 0.0 | 0% | −73% | 0% | −49% |

| R4 | 2.1 | 4% | 2.7 | 3% | −15% | 0.6 | 1% | 1.2 | 1% | 13% | −13% | 29% |

| R5 | 4.7 | 9% | 7.3 | 9% | 4% | 2.7 | 4% | 4.5 | 4% | −9% | −2% | 3% |

| R6 | 0.4 | 1% | 2.1 | 3% | 203% | 3.2 | 5% | 12.8 | 11% | 119% | 12% | −2% |

| R7 | 0.9 | 2% | 0.6 | 1% | −53% | 9.3 | 15% | 22.8 | 20% | 35% | −224% | 6% |

| R8 | 14.3 | 27% | 20.6 | 25% | −5% | 12.0 | 19% | 19.8 | 17% | −10% | −6% | 7% |

| R9 | 6.3 | 12% | 11.7 | 14% | 22% | 6.2 | 10% | 11.4 | 10% | 0% | 0% | −1% |

| R10 | 4.9 | 9% | 7.4 | 9% | −1% | 13.0 | 21% | 19.6 | 17% | −17% | 0% | 0% |

| R11 | 5.0 | 9% | 7.3 | 9% | −4% | 5.4 | 9% | 6.4 | 6% | −35% | 10% | −11% |

| R12 | 2.5 | 5% | 4.6 | 6% | 22% | 2.1 | 3% | 3.5 | 3% | −10% | 5% | −7% |

| R13 | 5.5 | 10% | 7.7 | 10% | −7% | 6.5 | 10% | 10.2 | 9% | −14% | −6% | 5% |

| R14 | 1.8 | 3% | 2.9 | 4% | 2% | 0.6 | 1% | 0.8 | 1% | −28% | 4% | −14% |

| R15 | 0.8 | 1% | 1.4 | 2% | 13% | 0.1 | 0% | 0.3 | 0% | 58% | −8% | 35% |

| Chile | 53.4 | 100% | 81.1 | 100% | 62.5 | 100% | 114.0 | 100% | −11% | 8% | ||

| Food−Related Industries | ||||||||||||

| Region | DVC | GVC | Variation on Composition | |||||||||

| 2008 | (%) | 2015 | (%) | Relative Variation | 2008 | (%) | 2015 | (%) | Relative Variation | DVC | GVC | |

| R1 | 1.5 | 1.5% | 1.1 | 0.8% | −44.3% | 0.8 | 0.2% | 0.1 | 0.0% | −84.1% | 27.5% | −245.2% |

| R2 | 2.2 | 2.3% | 2.3 | 1.8% | −21.3% | 3.1 | 0.6% | 1.4 | 0.3% | −54.1% | 33.6% | −55.1% |

| R3 | 2.1 | 2.1% | 1.3 | 1.0% | −52.4% | 10.1 | 2.1% | 3.9 | 0.8% | −60.9% | 33.0% | −11.1% |

| R4 | 2.3 | 2.4% | 2.4 | 1.8% | −22.1% | 0.1 | 0.0% | 0.1 | 0.0% | −1.0% | 0.3% | −6.8% |

| R5 | 1.6 | 1.7% | 1.7 | 1.3% | −19.9% | 0.4 | 0.1% | 0.2 | 0.0% | −44.9% | 10.5% | −77.4% |

| R6 | 4.8 | 5.0% | 14.1 | 10.8% | 118.5% | 31.1 | 6.4% | 40.5 | 8.5% | 33.2% | 47.8% | −16.6% |

| R7 | 36.5 | 37.5% | 49.3 | 38.0% | 1.2% | 368.2 | 75.4% | 343.6 | 71.9% | −4.6% | 28.0% | −4.0% |

| R8 | 4.9 | 5.1% | 4.5 | 3.5% | −30.9% | 8.2 | 1.7% | 8.2 | 1.7% | 1.4% | −4.8% | 2.7% |

| R9 | 5.3 | 5.4% | 5.6 | 4.3% | −19.9% | 6.9 | 1.4% | 7.2 | 1.5% | 5.5% | 1.9% | −1.5% |

| R10 | 17.4 | 17.9% | 22.1 | 17.0% | −5.0% | 38.0 | 7.8% | 46.7 | 9.8% | 25.6% | 2.0% | −0.9% |

| R11 | 2.4 | 2.5% | 2.8 | 2.2% | −14.0% | 3.6 | 0.7% | 3.6 | 0.8% | 2.0% | 7.7% | −6.0% |

| R12 | 4.8 | 5.0% | 5.3 | 4.0% | −18.6% | 4.3 | 0.9% | 4.0 | 0.8% | −4.1% | 6.4% | −8.3% |

| R13 | 4.9 | 5.1% | 11.2 | 8.6% | 70.7% | 6.7 | 1.4% | 14.5 | 3.0% | 123.2% | 2.3% | −1.8% |

| R14 | 0.8 | 0.8% | 1.2 | 0.9% | 16.4% | 0.1 | 0.0% | 0.1 | 0.0% | 48.4% | 0.4% | −6.4% |

| R15 | 5.7 | 5.9% | 4.9 | 3.8% | −35.5% | 6.4 | 1.3% | 3.4 | 0.7% | −44.8% | 19.6% | −28.1% |

| Chile | 97.4 | 100.0% | 129.8 | 100.0% | 488.0 | 100.0% | 477.6 | 100.0% | 22.2% | −6.0% | ||

| Food−Services | ||||||||||||

| Region | DVC | GVC | Variation on Composition | |||||||||

| 2008 | (%) | 2015 | (%) | Relative Variation | 2008 | (%) | 2015 | (%) | Relative Variation | DVC | GVC | |

| R1 | 0.7 | 0.8% | 0.8 | 0.5% | −32.5% | 0.1 | 0.1% | 0.0 | 0.0% | −62.1% | 5.0% | −163.3% |

| R2 | 1.6 | 1.8% | 2.2 | 1.4% | −20.2% | 0.8 | 1.2% | 0.6 | 0.9% | −27.5% | 13.2% | −48.8% |

| R3 | 1.0 | 1.1% | 0.8 | 0.5% | −51.6% | 0.3 | 0.4% | 0.3 | 0.4% | −11.9% | −3.6% | 11.4% |

| R4 | 1.6 | 1.7% | 1.8 | 1.2% | −30.6% | 0.1 | 0.2% | 0.1 | 0.1% | −26.4% | 2.0% | −43.9% |

| R5 | 1.3 | 1.4% | 1.6 | 1.0% | −25.9% | 0.4 | 0.6% | 0.3 | 0.5% | −22.4% | 7.9% | −37.1% |

| R6 | 0.5 | 0.6% | 1.3 | 0.9% | 58.9% | 0.8 | 1.2% | 1.1 | 1.6% | 32.8% | 27.9% | −34.3% |

| R7 | 77.6 | 85.7% | 133.4 | 88.0% | 2.7% | 58.2 | 92.8% | 62.7 | 92.9% | 0.2% | 16.0% | −34.1% |

| R8 | 1.5 | 1.7% | 1.5 | 1.0% | −40.9% | 0.6 | 1.0% | 0.5 | 0.8% | −21.7% | 4.4% | −12.5% |

| R9 | 0.8 | 0.9% | 1.2 | 0.8% | −10.7% | 0.2 | 0.3% | 0.3 | 0.4% | 34.3% | 0.7% | −2.8% |

| R10 | 0.6 | 0.6% | 1.1 | 0.7% | 12.5% | 0.6 | 1.0% | 0.7 | 1.1% | 11.3% | 18.9% | −27.7% |

| R11 | 0.7 | 0.8% | 1.4 | 0.9% | 15.4% | 0.3 | 0.4% | 0.3 | 0.5% | 13.4% | 9.9% | −42.8% |

| R12 | 0.6 | 0.6% | 1.0 | 0.6% | −0.9% | 0.1 | 0.1% | 0.1 | 0.1% | −10.5% | 4.8% | −64.2% |

| R13 | 0.8 | 0.9% | 1.2 | 0.8% | −8.4% | 0.3 | 0.5% | 0.3 | 0.5% | 1.7% | 7.7% | −29.5% |

| R14 | 0.5 | 0.5% | 0.8 | 0.6% | 6.2% | 0.0 | 0.0% | 0.0 | 0.0% | −10.0% | 1.0% | −82.0% |

| R15 | 0.8 | 0.9% | 1.4 | 0.9% | 5.7% | 0.1 | 0.1% | 0.1 | 0.1% | 22.2% | 2.1% | −32.0% |

| Chile | 90.5 | 100.0% | 151.6 | 100.0% | 62.7 | 100.0% | 67.5 | 100.0% | 14.7% | −32.9% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanguinet, E.R.; García-García, F.d.B. Rural-Urban Linkages: Regional Financial Business Services’ Integration into Chilean Agri-Food Value Chains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410863

Sanguinet ER, García-García FdB. Rural-Urban Linkages: Regional Financial Business Services’ Integration into Chilean Agri-Food Value Chains. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410863

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanguinet, Eduardo Rodrigues, and Francisco de Borja García-García. 2023. "Rural-Urban Linkages: Regional Financial Business Services’ Integration into Chilean Agri-Food Value Chains" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410863