Education in Tourism—Digital Information as a Source of Memory on the Examples of Places Related to the Holocaust in Poland during World War II

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism and Information

2.2. Internet and Education

2.3. Tourism and Education

3. Research Questions, Methods, and Source of Research Material

- -

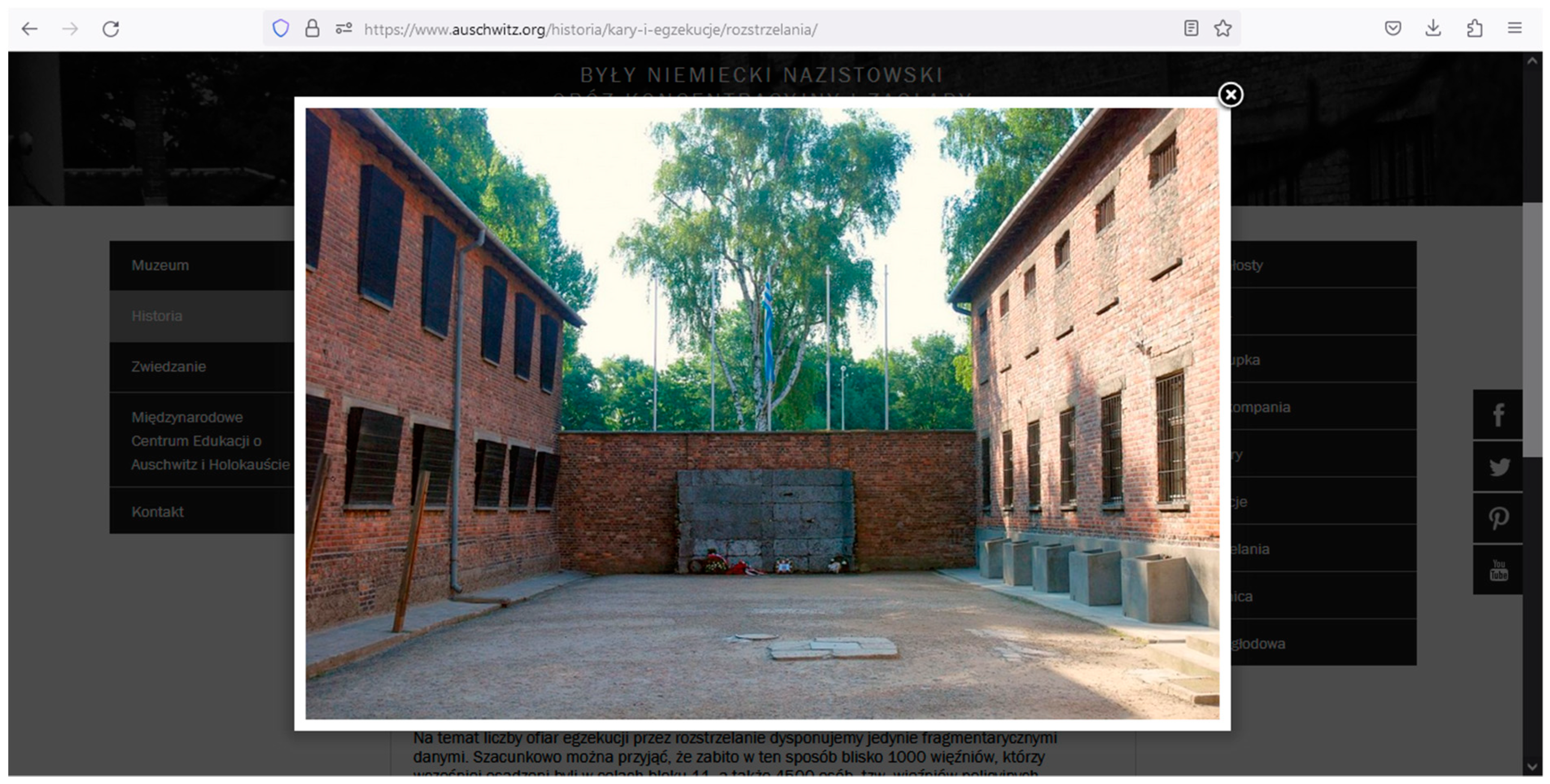

- Memorial and museum Auschwitz-Birkenau: Former German Nazi Concentration and Extermination camp [129];

- -

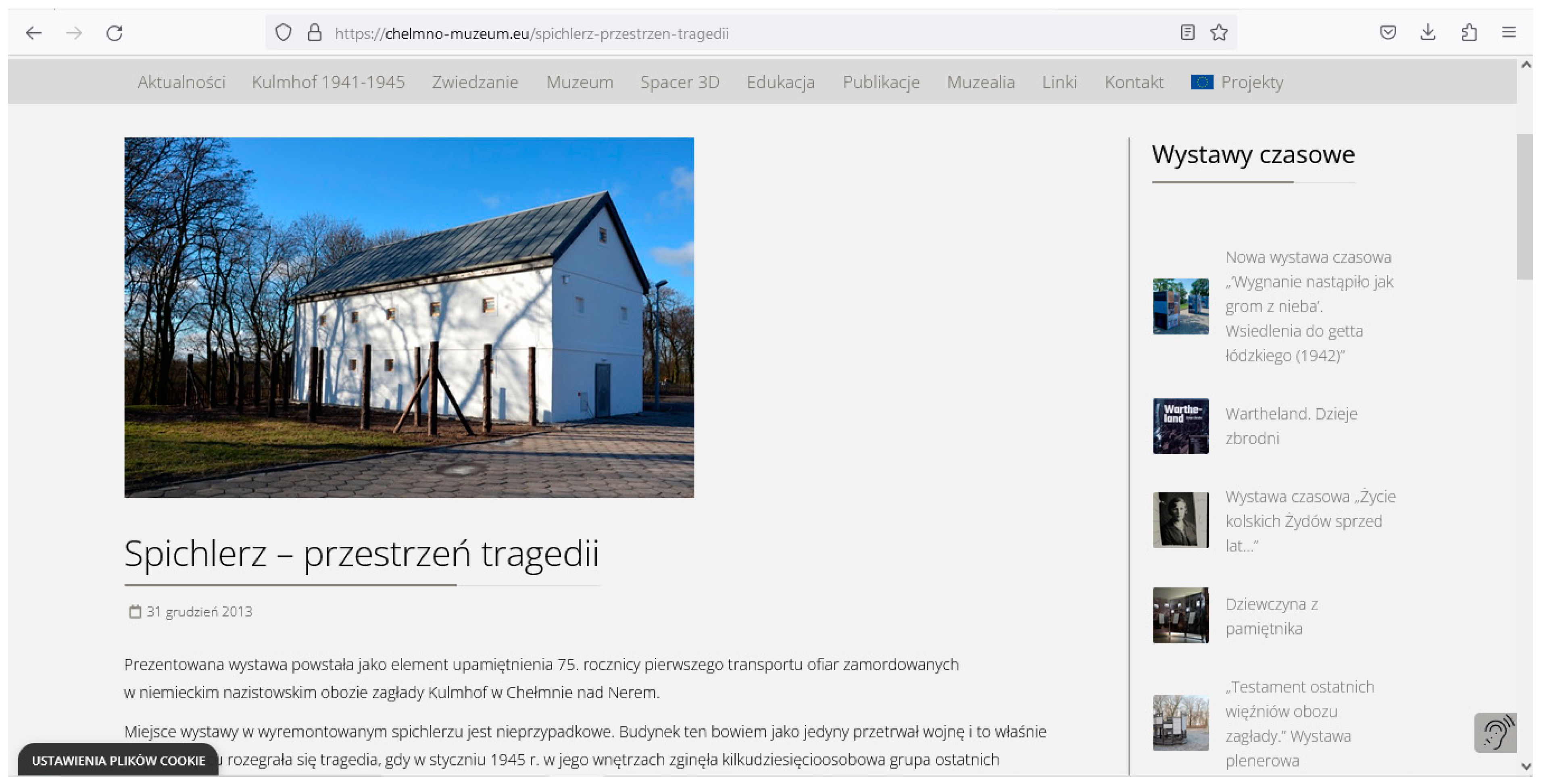

- Museum of the Former German Kulmhof Death Camp in Chełmno on Ner [130];

- -

- State Museum at Majdanek: The German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1941–1944) [131];

- -

- Museum and Memorial in Bełżec: The Nazi German Extermination Camp (1942–1943) [132];

- -

- Museum and Memorial in Sobibór: The Nazi German Extermination Camp (1942–1943) [133];

- -

- Treblinka museum: The Nazi German Extermination and Forced Labour Camp (1941–1944) [134];

- -

- Stutthof Museum: The German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1939–1945) [135];

- -

- KL Plaszow Museum [136].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Main Information

4.1.1. The History of the Camp—Methods of Presentation

4.1.2. History of the Museum—Methods of Presentation

- -

- From liberation to the founding of the museum: hospitals; the work of the commission for investigating the crimes of the Nazis; transit camps; use of post-camp property; activities for the creation of the museum; visiting the post-camp areas; opening of the museum.

- -

- The beginnings of the functioning of the museum: Auschwitz I; Auschwitz II-Birkenau; number of visitors; first scientific studies; national exhibitions, monument in birkenau; press discussion; demolish and plough?

- -

- Museum by dates: tabs contain information for individual decades from 1945 to 2022 [129].

4.1.3. Visiting the Museum—Information

4.1.4. Virtual Tour

4.1.5. Selected Exhibitions

4.1.6. Selected Publications Available on Museum Websites

4.2. Complementary Information

4.2.1. News

4.2.2. Teaching Aids

4.2.3. Temporary Exhibitions

4.2.4. Other Channels of Complementary Information Distribution

4.3. Heritage and Form of Transmission

4.4. Modes of Narration—Official and Personal

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashworth, G.J. Heritage, Tourism and Places: A Review. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2000, 25, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged Authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The Core of Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Chen, F. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Wall, G. Chinese Research on World Heritage Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. 2011, 16, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, F.; Kock, F.; Josiassen, A. Cultural heritage authenticity: A producer view. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Santa-Cruz, F.; Lopez-Guzman, T. Culture, tourism and World Heritage Sites. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Su, W. Is the World Heritage just a title for tourism? Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 12748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunbridge, J.E.; Ashwotrh, G.J. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource of Conflict; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lähdesmäki, T.; Passerini, L.; Kaasik-Krogerus, S.; Huis, I. (Eds.) Dissonant Heritages and Memories in Contemporary Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V. From thanatopsis to than tourism: Guided by the dark. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 1996, 2, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lennon, J.; Foley, M. Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster; Continuum: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V.; Lennon, J.J. New Horizons in Tourism: Strange Experiences and Stranger Practices; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P.R. Consuming dark tourism: A Thanatological Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 3, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharpley, R.; Stone, P. The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, M.; Pezzullo, C. What’s so ’Dark’ about ’Dark Tourism’?: Death, Tours, and Performance. Tour. Stud. 2010, 9, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoshen, J.S. Dark Tourism Motivations: Simulation, Emotional Contagion and Topographic comparison. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H.; Schrier, T.; Xu, S. Dark tourism: Motivations and visit intentions of tourists. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2022, 36, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. Balancing the vocational: The theory and practice of liberal education in tourism. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2000, 2, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. The philosophic practitioner. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2002, 29, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, B.; Carr, N.; Cooper, C.P. Managing Educational Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Caton, K.; Belhassen, Y. On the need for critical pedagogy in tourism education. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffy, V.; Tribe, J.; Airey, D. Lifelong Learning for Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1402–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Vogelaar, A.; Hale, B. Towards sustainable educational travel. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGladdery, C.A.; Lubbe, B.A. Rethinking educational tourism: Proposing a new model and future directions. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomasi, S.; Paviotti, G.; Cacicchi, A. Educational Tourism and Local Development: The Role of Universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek-Żulicka, A.; Mokras-Grabowska, J. Creative approach to tourism through creative approach to didactics. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C. Vacationscapes: Designing Tourist Regions; Van Nostrand: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Beritelli, P.; Bieger, T.; Laesser, C. The impact of the Internet on information sources portfolios: Insight from a mature market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 22, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.B.; Kim, D.; Morrison, A.M. The relationships of meeting planners’ profiles with usage and attitudes toward the use of technology. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2005, 7, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C.; Abrantes, J.L.; Lages, L.F. The impact of using non-media information sources on the future use of mass media information sources: The mediating role of expectations fulfilment. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buhalis, D.; Jun, S.H. E-Tourism. Contemporary Tourism Reviews. 2011. Available online: http://www.goodfellowpublishers.com/free_files/fileEtourism.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Llodra-Riera, I.; Martinez-Ruiz, M.; Jimenez-Zarco, A.; Izquierdo-Yuta, A. A multidimensional analysis of the information sources construct and its relevance for destination image formation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, P.; Ganthan, N.; Bharanidharan, H. A Systematic Literature Review: Information Accuracy Practices in Tourism. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ukpabi, D.; Karjaluoto, H. Consumers’ acceptance of information and communications technology in tourism: A review. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 618–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social Media in Tourism and Hospitality: A Literature Review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet, the state of e-tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papathanassis, A.; Knolle, F. Exploring the adoption and processing of online holiday reviews: A grounded theory approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Licata, C. The future of e-tourism intermediaries. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswas, D. Economics of information in the web economy: Towards a new theory? J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.I.; Wei, P.L.; Chen, J.H. Influential factors and relational structure of Internet banner advertising in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Kim, D.; Morrison, A.M. The effect of prior destination experience on online information search behaviour. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2006, 6, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Yuan, Y.; Fesenmaier, D. Preparing for the new economy: Advertising strategies and change in destination marketing organizations. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A. Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M. Projected destination image online: Website content analysis of pictures and text. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2004, 7, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Brinberg, D. Affective images of tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 1997, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; Garcia, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende-Parker, A.M.; Morrison, A.M.; Ismail, J.A. Dazed and confused? An exploratory study of the image of Brazil as a travel destination. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.; Jang, S.C. The effects of perceived price and brand image on value and purchase intention: Leisure travelers’ attitudes toward online hotel booking. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2006, 15, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Cheung, C. A study of the perceived importance of the overall website quality of different classes of hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Hsu CH, C. Importance of hotel website dimensions and attributes: Perceptions of online browsers and online purchasers. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2006, 30, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Song, H.J.; Lee, C.; Petrick, J.F. An integrated model of pop culture fans’ travel decision-making processes. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, B.; Archer-Brown, C.; Colliander, J.; Lambert, A. Vacation posts on Facebook: A model for incidental vicarious travel consumption. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1014–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bai, B.; Law, R.; Wen, I. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intentions: Evidence from Chinese online visitors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Elia, E.; Di Pace, R.; Bifulco, G.N.; Shiftan, Y. The impact of travel information’s accuracy on route-choice. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 26, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, H.; Silva, E.S.; Antonakakis, N.; Filis, G.; Gupta, R. Forecasting accuracy evaluation of tourist arrivals. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 63, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, P.A.; Wang, G.; Cavka, H.B.; Staub-French, S.; Pottinger, R. Information quality assessment for facility management. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 33, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Duan, L. The concept of smart tourism in the context of tourism information services. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M.; Zyl, C. Electronic word-of-mouth and online reviews in tourism services: The use of twitter by tourists. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, R.; Fischbach, K.; Schoder, D. Mineable or messy? Assessing the quality of macro-level tourism information derived from social media. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Trust and involvement in tourism social media and web-based travel information sources. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Fernández, A.C.; Gómez, M.; Aranda, E. Differences in the city branding of European capitals based on online vs. offline sources of information. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, C.; Scannapieco, M. Data Quality Dimensions Data and Information Quality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, C. The influence of tourism website on tourists’ behavior to determine destination selection: A case study of creative economy in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 96, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Examining e-travel sites: An empirical study in Taiwan. Online Inf. Rev. 2010, 34, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobar-Rodriguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Online drivers of consumer purchase of website airline ticket. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2013, 32, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Law, R. Analysing the intention to purchase on hotel websites: A study of travellers to Hong Kong. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Vogt, C. A structural analysis of destination travel intentions as a function of web site features. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E.C.S.; Chen, C. Cultivating traveler’s revisit intention to e-tourism service: The moderating effect of website interactivity. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2015, 34, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; O’Connor, P. Information Communication Technology Revolutionizing Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, R.; Leung, R.; Buhalis, D. Information technology applications in hospitality and tourism: A review of publications from 2005 to 2007. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pyo, S. Knowledge map for tourist destinations—Needs and implications. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, S.; Beneventano, D.; Guerra, F.; Vincini, M. Building a tourism information provider with the MOMIS system. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2005, 7, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widawski, K.; Rozenkiewicz, A.; Łach, J.; Krzemińska, A.; Oleśniewicz, P. Geotourism starts with the accessible information: The Internet as a promotional tool for the georesources of Lower Silesia. Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widawski, K.; Oleśniewicz, P. Thematic Tourist Trails: Sustainability Assessment Methodology. The Case of Land Flowing with Milk and Honey. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corfu, A.; Kastenholz, E. The opportunities and limitations of the Internet in providing a quality tourist experience: The case of ‘‘Solares De Portugal’’. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2005, 6, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, S.H. Designing culturally compatible Internet gaming sites. UNLV Gaming Res. Rev. J. 2006, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Molz, J.G. Travel Connections: Tourism, Technology and Togetherness in a Mobile World; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, B.; Pan, G.W. Chinese outbound tourists: Understanding their attitudes, constraints and use of information sources. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chow, I.; Murphy, P. Predicting intended and actual travel behaviours: An examination of Chinese outbound tourists to Australia. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.W.; Law, R. A novel English/Chinese information retrieval approach in hotel website searching. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, I.; Papamichail, K. Information tools for cultural tourism destinations: Managing accessibility. ToSEE Tour. South. East. Eur. 2021, 6, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Michopoulou, E. Information-Enabled Tourism Destination Marketing: Addressing the Accessibility Market. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, R. Determinants of Search for Nondurable Goods: An Empirical Assessment of the Economics of Information Theory. J. Consum. Aff. 1996, 30, 390–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; McCleary, K. An Integrative model of tourists’ information search behaviour. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M. Destination image representation on the web: Content analysis of Macau travel related websites. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, M. Online destination image of India: A consumer based perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Morrison, A.M. Russia’s destination image among American pleasure travellers. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.A.; Feng, R.; Breiter, D. Tourist purchase decision involvement and information preferences. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Jalilvand, M.; Samiei, N.; Dini, B.; Yaghoubi Manzari, P. Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. eCRM 2.0 applications and trends: The use and perceptions of Greek tourism firms of social networks and intelligence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 7, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Gartner, W.C. Destination image and its functional relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R. Deconstructing destination image in the information age. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2003, 6, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K.J.; Couldwell, C.M. Using visitor-employed photography to investigate destination image. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggam, K.; Almer, A. Acceptance of geo-multimedia applications in Austrian tourism organizations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Sigala, M., Mich, L., Murphy, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, S.; Agarwal, A. Use of multimedia as a new educational technology tool—A study. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2012, 2, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chronis, A. Between place and story: Gettysburg as tourism imaginary. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1797–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z. From digitization to the age of acceleration: On information technology and tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheldon, P.J. Tourism Information Technology; Cab International: Wallingford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theater and Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.; Lee, Y. The development of an e-travel service quality scale. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.J.; Lee, S. Developing information technology proficiencies and fluency in hospitality students. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2006, 18, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, J.F.; DeVeau, L.T. A computer software approach to teaching hospitality financial accounting. J. Hosp. Financial Manag. 2005, 13, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.H.; Dalbor, M.C.; McManus, A. Assessing the effectiveness of servsafe online. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2007, 19, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Gvili, Y. Heritage site websites content: The need for versatility. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2006, 15, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, K.; Xwhitney, D. Projecting Western Consumer Attitudes toward Travel to Six Eastern European Countries. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1994, 6, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. New technologies in tourism: From multi-disciplinary to anti-disciplinary advances and trajectories. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, M.; Christodoulou, Y.; Aliprantis, J.; Cardaki, G. ACUX Recommender: A Mobile Recommendation System for Multi-Profile Cultural Visitors Based on Visiting Preferences Classification. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, M.; Christodoulou, Y.; Alexandridis, G.; Teneketzis, A.; Caridakis, G. ACUX Typology: A Harmonistation of Cultural-Visitor Typologies for Multi-Profile Classification. Digital 2022, 2, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widawski, K. (Ed.) Turystyka Kulturowa na Dolnym Śląsku—Wybrane Aspekty; Rozprawy Naukowe Instytut Geografii i Rozwoju Regionalnego Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2009; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky-Porges, N. The Grand Tour: Travel as an Educational Device: 1600–1800. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, J. The Holiday Makers: Undertanding the Impact of Leisure and Travel; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A. Tourism, Technology and Competitive Strategies; CAB International: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Jenner, P. Market segments: Educational tourism. Travel Tour. Anal. 1997, 3, 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. World culture and heritage and tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2000, 25, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Managing Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Benckendorff, P. Travel and learning: A neglected tourism research area. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolby, N. Encountering an American self: Study abroad and national identity. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2004, 48, 150–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K.; Dierking, L. Conservation learning in wildlife tourism settings: Lessons from research in zoos and aquariums. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Hwang, Y.H. User-generated destination image through weblogs: A comparison of pre-and post-visit images. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, A. International tourists’ image of Zhangjiajie, China: Content analysis of travel blogs. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 5, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, M.A.; Joseph, S.M.; Dai, M. International versus domestic visitors: An examination of destination image perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.auchwitz.org (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Available online: www.chelmno-muzeum.eu (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Available online: www.majdanek.eu (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Available online: www.belzec.eu (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Available online: www.sobibor-memorial.eu (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Available online: https://muzeumtreblinka.eu (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Available online: https://stutthof.org (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Available online: https://plaszow.org (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Tse, T.S.; Zhang, E.Y. Analysis of blogs and microblogs: A case study of chinese bloggers sharing their Hong Kong travel experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; McKercher, B. The tourism data gap: The utility of official tourism information for the hospitality and tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subpage | Content |

|---|---|

| General history | The reason for establishing the camp, its structure, and the manner of its establishment are presented. The description is accompanied by a characteristic photo. |

| Before the Holocaust | A description of the reasons for establishing the camp from the very beginning. The road to Auschwitz is divided into subsequent stages. Each of the stages is described on a different subpage: popularity of the Nazis; Hitler’s rise to power; persecution of Jews; emigration and the Jewish problem; founding of KL Auschwitz; Einsatzgruppen. |

| Auschwitz I | Information on the division of the camp, description of the construction and expansion of this part of the camp, and active links to online lessons: Auschwitz—concentration and extermination camp and a link to books on this subject, which can be purchased in the online store |

| Auschwitz II—Birkenau | The history and role of this camp presented in text + photo format with three subpages informing about construction of the camp (the text is accompanied by an active photo), organizational structure of the camp, and camp functions. |

| Auschwitz III—Monowitz | Description divided into five parts referring to five subpages: IG Farben; beginning of construction; numerical status; conditions and number of casualties; evacuation. Each piece of information is presented as text ranging from two sentences to several paragraphs long. |

| Sub-camps | 49 sub-camps are shown. One sentence of information is devoted to each of them, while the name of the sub-camp itself is an active link that redirects to a separate subpage. Sometimes the description is accompanied by a photo. |

| Holocaust | The website refers to six subpages that describe the Holocaust: Jews; gas chambers; unloading ramps and selections; course of annihilation; destruction of the gas chambers; number of victims. |

| Different groups of prisoners | A set of texts relating to six categories: Jews; Polish people; Roma; Soviet prisoners of war; Auschwitz prisoners of other nationalities; homosexuals—a separate category of prisoners. |

| Prisoner markings | The information leads to three subpages: marking with a triangle; marking jews; other markings. Each of the subpages explains the markings in a few sentences. |

| The fate of children | The link leads to seven subpages: Jewish children; Roma children; Polish children; children from the Soviet Union; children born in the camp; the fate of children; number of liberated children. Each of the subpages contains a few-sentence description. |

| Life in the camp | Text with two active photos related to the topic. There are three subpages: dining; agenda of the day; releases from the camp. Each subpage is a separate text. |

| Punishments and executions | Introductory text and nine subpages: punishment of whipping; block 11; “the post” penalty; penal company; other penalties; executions; shootings; the gallows; starvation death. Each subpage is accompanied by an explanation of varying length. |

| Camp hospitals | Text about medicine in Auschwitz and seven subpages: selections, executions, experiments; inception of hospitals; diseases and epidemics; conditions in the hospital; prisoner-doctors; selections and lethal intravenous injections; falsifying of hospital records. Each subpage is a few-paragraph-long text describing the phenomenon. |

| Experiments | Information about medical experiments carried out on prisoners in the camp and eight subpages: seven dedicated to specific doctors—German criminals, and tabs with the names of people, e.g., Josef Mengele; the eighth tab describes other doctors (criminals). |

| Resistance movement | Introductory text + photo of Pilecki and five subpages: organized resistance; prisoner mutinies; escapes; reports written after escaping from Auschwitz; number of escapes. |

| Informing the world | Text and four subpages: first covered contacts with prisoners; collecting evidence of crime; transferring information to the West; reports of Auschwitz escapees. |

| Evacuation | Text + four pages: preliminary evacuation of the camp; cessation of mass extermination; final evacuation and liquidation of the camp; on the trail of the death marches—information of varying length. |

| Liberation | Text + six subpages: escape of the SS men and the final victims; 27 January 1945; film that documents the crime; first help; liberated children; war crimes’ investigatory commissions. Each tab is text of varying length developing the topic. |

| Number of victims | Text + three pages: number of deportees by ethnicity; number of prisoners registered by year; overall numbers by ethnicity or category of deportee. Each subpage presents statistical data related to the topic. |

| The SS garrison | Description characterizing the crew members in terms of education, religion, citizenship, SS overseers. There are five subpages: commandants; command hierarchy; the organizational structure of Auschwitz concentration camp; trials of SS men from the Auschwitz Concentration Camp garrison; (un)justice. Each subpage is accompanied by textual information. |

| Holocaust denial | A longer text describing the phenomenon with six subpages: Holocaust and genocide denial after the war; denial forms; Leuchter Report; Germar Rudolph; The Institute for Historical Review; Ernst Zundel. Each tab is accompanied by relevant text. |

| Bibliography | List of authors and their publications |

| Photo galery | The gallery is divided into 15 categories. Each category contains photos + descriptions. |

| Auschwitz calendar | Seven subpages briefly describing the events in each of the 7 years of the war (from 1939 to 1945) with a daily date. |

| Offer | Description |

|---|---|

| Memory 4.0 | Memory 4.0—an online educational tool for international youth groups. It is a package of six interconnected lessons on the persecution of Poles and people of other nationality as political prisoners, racist persecution of Jews, racist persecution of Roma and Sinti and other types of persecution. It is preceded by an introduction and ends with a summary. It is a project developed in English and partly in Hebrew. |

| Lessons | Online lesson offer. Each of the lessons is developed by professional historians. The offer includes 29 different lessons, which are enriched with multimedia material: photos, videos, interactive maps, and plans, so as to make it easier to understand the history of not only this place but also the events that led to its creation. There are various topics that concern selected issues. These topics—among others—are women in KL Auschwitz, deportations of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz, the resistance movement in KL Auschwitz, etc. Two lessons are worth paying attention to: introductory lessons on Auschwitz—concentration and extermination camp and extermination of Jews at KL Auschwitz. The first, due to the content, can be practically classified as information of a general nature. Its uniqueness also lies in the fact that it has been proposed in 10 language versions, including Hebrew, Arabic, and even Persian. The other lesson about the extermination of Jews is basically a series of seven lessons describing the attempt to exterminate the Jewish people. |

| “On Auschwitz” podcast | These are recordings presenting various topics related to the camp in 30 episodes. Duration varies from 13 to 48 min, depending on the complexity of the topic. |

| To Understand Holokaust | A book supporting teaching about the extermination of Jews. This is an extensive publication (354 pages) produced by the museum, available free of charge. It presents, in addition to the tragedy of the Holocaust itself, the culture and history of Jews in Europe, as well as their heritage and contribution to the development of the contemporary world. |

| Multimedia presentations for the publication “Voices of Memory” | Didactic publication devoted to issues related to the camp. These are nine multimedia presentations available for free on the website for teachers to download. |

| Artwork of prisoners in KL Auschwitz | Teaching materials for educators in the form of readymade lesson plans. |

| Educational package: Polish citizens in KL Auschwitz | The package consists of three elements: a documentary film (40 min), a lesson designed on the Prezi platform with a scenario for teachers and worksheets, and reflection cards for students—all in a free downloadable version. The lesson is available in three languages: Polish, English, and Hebrew. |

| Education portfolio—75 years after Aktion Reinchardt | Contemporary Remembrance of the Holocaust of Polish Jews: the contents of the scenarios contained therein are divided into two groups: the local history of the Jewish community and five scenarios relating to general issues related to the culture and the Holocaust of Jews. The electronic version of the scenarios is a total of 110 pages of text to download in PDF version. |

| Movie | A two-part recording of the educational conference “Memory in us is still immature...” devoted to the issues of how to teach about Auschwitz and the Holocaust. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Widawski, K.; Oleśniewicz, P. Education in Tourism—Digital Information as a Source of Memory on the Examples of Places Related to the Holocaust in Poland during World War II. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410903

Widawski K, Oleśniewicz P. Education in Tourism—Digital Information as a Source of Memory on the Examples of Places Related to the Holocaust in Poland during World War II. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410903

Chicago/Turabian StyleWidawski, Krzysztof, and Piotr Oleśniewicz. 2023. "Education in Tourism—Digital Information as a Source of Memory on the Examples of Places Related to the Holocaust in Poland during World War II" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410903