Internet Use, Subjective Well-Being, and Environmentally Friendly Practices in Rural China: An Empirical Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Internet Use on EAPs in Agriculture Activities

2.2. SWB on EAPs in Agriculture Activities

2.3. Internet Use on SWB and Intermediary Effect

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Research Population and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Personal and Familial Characteristics

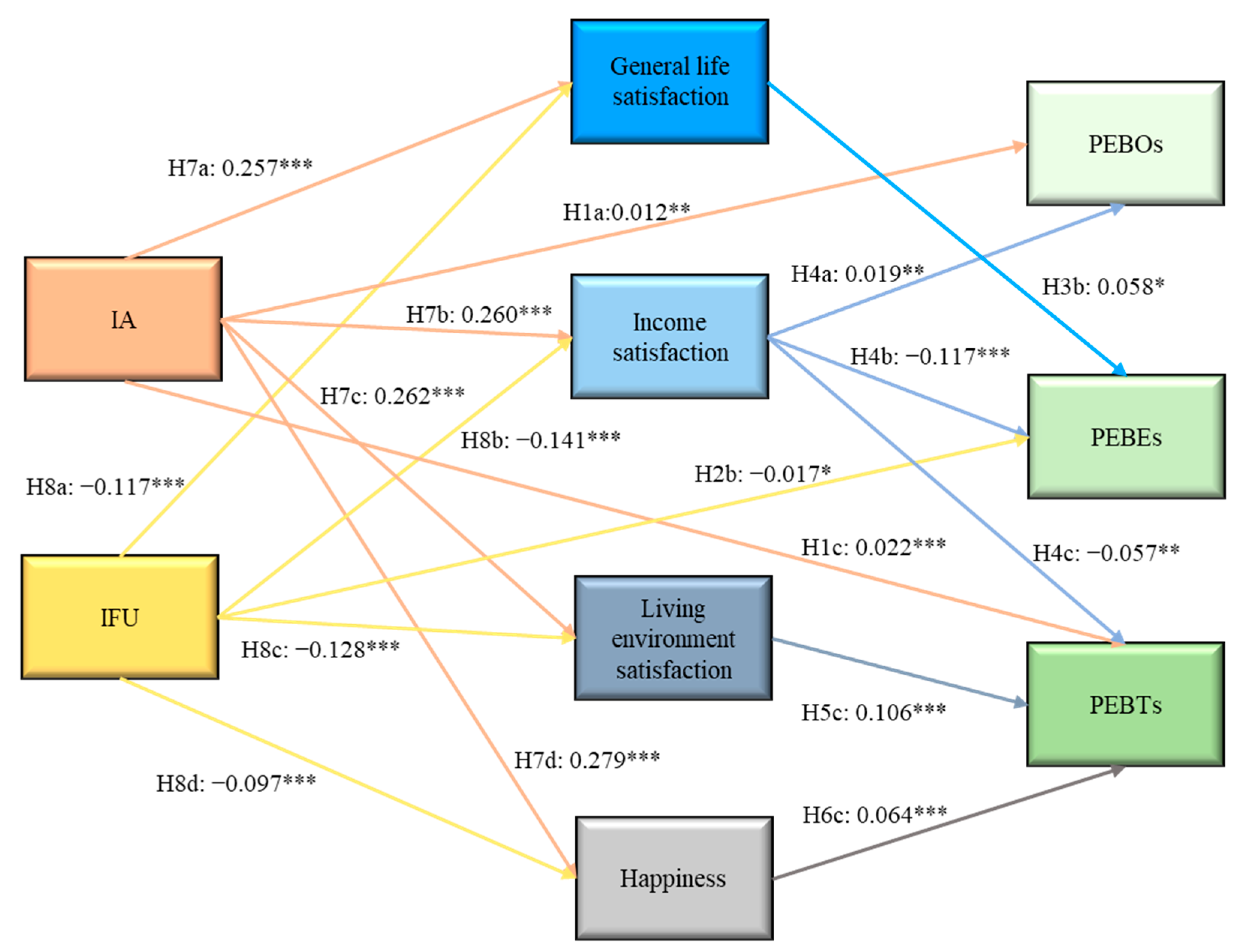

4.2. Path Analysis Results

4.3. Results of Indirect Effects

4.4. Influence of Control Variables

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| EAPs | Environmentally friendly agricultural practices. |

| EAPOs | EAPs resulting in output loss. |

| EAPEs | EAPs involving additional expenses. |

| EAPTs | EAPs requiring more time investment. |

| SWB | Subjective well-being. |

| IA | Internet access. |

| IFU | Internet function utilization. |

| CRRS | China Rural Revitalization Survey. |

References

- Novelli, S. Determinants of environmentally-friendly farming. Qual. Access Success 2018, 19, 340–346. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Qin, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Environmentally-friendly agricultural practices and their acceptance by smallholder farmers in China—A case study in Xinxiang County, Henan Province. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z. Assessment of effects of best management practices on agricultural non-point source pollution in Xiangxi River watershed. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 117, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.; Mahmood, H.; Iqbal, A. Environmentally friendly farming and yield of wheat crop: A case of developing country. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, X. Internet use and Chinese older adults’ subjective well-being (SWB): The role of parent-child contact and relationship. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resident Income and Consumption Expenditure in 2022. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901715.html (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Ojala, M. Coping with Climate Change among Adolescents: Implications for Subjective Well-Being and Environmental Engagement. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. Are pro-environmental consumption choices utility-maximizing? Evidence from subjective well-being data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Blankenberg, A.K.; Guardiola, J. Does it have to be a sacrifice? Different notions of the good life, pro-environmental behavior and their heterogeneous impact on well-being. Ecol Econ. 2020, 167, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheke, O.R.; Onyenorah, C.O. Awareness, Preferences and Adoption of Soil Conservation Practices among Farmers in Ohafia Agricultural Zone of Abia State, Nigeria. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2012, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zaibidi, N.Z.; Baten, M.A.; Ramli, R.; Kasim, M.M. Efficiency and Environmental Awareness of Paddy Farmers: Stochastic Frontier Analysis vs Data Envelopment Analysis. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2018, 7, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 47th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/03/content_5584518.htm (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Hong, Y.Z.; Chang, H.H. Does digitalization affect the objective and subjective wellbeing of forestry farm households? Empirical evidence in Fujian Province of China. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Huo, X.; Yin, R. Does computer usage change farmers’ production and consumption? Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019, 11, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, P.; Han, C.; Teng, M. The influence of Internet use on pro-environmental behaviors: An integrated theoretical framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénard, T.; Poussing, N.; Suire, R. Does the Internet make people happier? J. Socio Econ. 2013, 46, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lohmann, S. Information technologies and subjective well-being: Does the Internet raise material aspirations? Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2015, 67, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castellacci, F.; Schwabe, H. Internet Use and the U-Shaped Relationship between Age and Well-Being (No. 20180215); Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S. Study on Motivation and Incentives of Rural Household’s Ecological Behaviors in Under-Forest Economy Management. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2020; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, M.; Wang, F.; Yu, N. Internet use encourages pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Liobikienė, G.; Saadi, H.; Sepahvand, F. The influence of media usage on Iranian students’ pro-environmental behaviors: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Karami, E. Farmers’ pro-environmental behavior under drought: Application of protection motivation theory. J. Arid Environ. 2016, 127, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, C.; Tisdell, C. Why farmers continue to use pesticides despite environmental, health and sustainability costs. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 39, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arlinkasari, F.; Caninsti, R.; Radyanti, P.U. Will Happy People Preserve Their Environment. Ecopsy 2017, 4, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krekel, C.; Prati, A. Linking subjective wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour: A multidimensional approach. In Linking Sustainability and Happiness: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Rueda, N.; Wanden-Berghe, J.G. Where is the double dividend? The relationship between different types of pro-environmental behavior and different conceptions of subjective well-being. In Linking Sustainability and Happiness: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, H.; Bibby, P.A. Personality, fear of missing out and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, J.K.; Connolly, M.; Buchanan, A.; Hoxha, D.; Rosebrock, L.; Cacioppo, J.; Csernansky, J.; Wang, X. Neural substrates of negativity bias in women with and without major depression. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 109, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A.; Nimrod, G. Internet use and subjective well-being in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.K. China Rural Revitalization Survey Report; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Adamides, G.; Stylianou, A.; Kosmas, P.C.; Apostolopoulos, C.D. Factors Affecting PC and Internet Usage by the Rural Population of Cyprus. Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 14, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J. The influence of farmer demographic characteristics on environmental behaviour: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, M.L. Structural Equation Modeling: Operations and Applications of AMOS, 2nd ed.; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.N. Structural Equation Model and Stata Application, 1st ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Region | Name Of Provinces | Number of Counties | Number of Townships | Number of Villages | Number of Households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern | Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Shandong Province | 15 | 49 | 92 | 1152 |

| Central | Anhui and Henan Province | 10 | 30 | 60 | 735 |

| Western | Guizhou, Sichuan, Shaanxi Province, and Ningxia Hui autonomous region | 20 | 61 | 125 | 1573 |

| Northeastern | Heilongjiang Province | 5 | 16 | 31 | 373 |

| Total | 10 provinces | 50 | 156 | 308 | 3833 |

| Variable | Question | Option | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet access | What are your internet devices? | 0 = none; 1 = mobile phone; 2 = mobile phone/tablet/computer and other devices | 1.2113 | 0.5906 | 0 | 2 |

| How is your network? | 0 = very poor, often disconnected; 1 = occasionally disconnected; 2 = good | 1.3174 | 0.7253 | 0 | 2 | |

| Do you have difficulty using a smartphone? | 0 = very difficult; 1 = a little difficult; 2 = no difficulty | 1.4074 | 0.6948 | 0 | 2 | |

| Can you access information online when you need to? | 0 = no; 1 = general; 2 = yes | 1.2452 | 0.8324 | 0 | 2 | |

| Your average online time per day | 0 = within 1 h; 1 = 1 to 4 h; 2 = more than 4 h | 0.8478 | 0.6865 | 0 | 2 | |

| Internet function utilization | Do you use the following internet functions? | □ Social (such as WeChat, Weibo, etc.) □Entertainment (such as games, live broadcasts, and short videos) □ Learning and education and official business □ Paid use of network software or app □Electronic commerce (such as online live sales) □ Internet finance (such as Huabei) | 2.0737 | 1.3085 | 0 | 6 |

| SWBs | Your general satisfaction with life | 1 = very dissatisfied; 2 = relatively dissatisfied; 3 = general; 4 = quite satisfied; 5 = very satisfied | 4.0681 | 0.8481 | 1 | 5 |

| Your satisfaction with family income | 3.5516 | 1.0561 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Your satisfaction with the living environment | 4.0898 | 0.8341 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Your happiness | 1 = very unhappy; 2 = relatively unhappy; 3 = general; 4 = quite happy; 5 = very happy | 4.1491 | 0.8357 | 1 | 5 | |

| EAPs | Do you adopt the following EAPs? | □ Pesticide reduction □ Land rotation/fallow □ Avoid groundwater irrigation □ Chemical fertilizer reduction □ Treat straw in an environmentally friendly way (used as fertilizer, feed, fuel, etc.) □ Recycling pesticide packaging | 2.1328 | 0.8014 | 0 | 6 |

| Index | Option | Number | Proportion | Index | Option | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 3577 | 93.32% | Age 1 | 18–30 | 9 | 0.24% |

| Female | 256 | 6.68% | 31–40 | 331 | 8.77% | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 3516 | 91.73% | 41–50 | 961 | 25.47% | |

| Unmarried/Divorced/ Widowed | 317 | 8.27% | 51–60 | 1227 | 32.52% | ||

| Education1 | Illiteracy | 327 | 8.53% | >60 | 1245 | 33.00% | |

| Primary School | 1179 | 30.77% | Household Income (yuan/year) | <20,000 | 960 | 25.05% | |

| Middle School | 1744 | 45.51% | (20,000–40,000) | 745 | 19.44% | ||

| High School | 433 | 11.30% | (40,000–60,000) | 556 | 14.51% | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or above | 149 | 3.89% | (60,000–80,000) | 408 | 10.64% | ||

| Political Status1 | Member of The CPC or Democratic Party | 913 | 23.83% | (80,000–100,000) | 296 | 7.72% | |

| Nonparty Personage | 2918 | 76.17% | >100,000 | 868 | 22.65% |

| Path | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| IA → EAPOs | 0.012 ** | 0.001 | 0.013 *** |

| IA → EAPEs | −0.002 | −0.003 * | −0.005 |

| IA → EAPTs | 0.022 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.028 *** |

| IFU → EAPOs | 0.008 | −0.001 | 0.007 |

| IFU → EAPEs | −0.017 * | 0.003 ** | −0.014 |

| IFU → EAPTs | 0.001 | −0.004 ** | −0.003 |

| Internet Use | SWB | EAPs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Access | Internet Function Utilization | General Life Satisfaction | Income Satisfaction | Living Environment Satisfaction | Happiness | Output Loss | Cost Money | Spend Time | |

| Sex | 0.013 | −0.006 | −0.018 | −0.008 | −0.020 | 0.002 | −0.025 | −0.012 | −0.002 |

| (0.76) | (−0.38) | (−1.13) | (−0.51) | (−1.22) | (0.12) | (−1.5) | (−0.44) | (−0.07) | |

| Age | −0.242 *** | −0.339 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.119 *** | 0.065 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.018 | 0.015 |

| (−13.81) | (−21.48) | (6.92) | (6.69) | (3.57) | (6.88) | (0.87) | (0.7) | (0.56) | |

| Marital Status | 0.000 | 0.006 | −0.012 | 0.004 | 0.026 | −0.039 | −0.004 | 0.026 | −0.001 |

| (0.01) | (0.38) | (−0.73) | (0.23) | (1.61) | (−2.36) | (−0.23) | (1.02) | (−0.03) | |

| Education | 0.164 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.015 | −0.008 | −0.022 | 0.028 | 0.024 | 0.010 | 0.031 |

| (9.49) | (7.24) | (0.87) | (−0.44) | (−1.27) | (1.64) | (1.31) | (0.37) | (1.15) | |

| Political Status | 0.078 *** | 0.050 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.104 *** | 0.019 | 0.053 *** | −0.013 | −0.030 | 0.012 |

| (4.74) | (3.12) | (3.74) | (6.4) | (1.15) | (3.26) | (−0.74) | (−1.25) | (0.51) | |

| Family Income | 0.202 *** | 0.175 *** | 0.057 *** | 0.118 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.009 | 0.070 *** | 0.014 |

| (13.08) | (11.38) | (3.46) | (7.29) | (3.22) | (4.59) | (0.55) | (2.56) | (0.52) | |

| Constants | 3.321 | 2.718 | 3.617 | 2.121 | 3.990 | 3.677 | 0.503 | 0.653 | 1.623 |

| (23.74) | (21.18) | (22.43) | (13.77) | (24.58) | (22.83) | (2.88) | (2.67) | (6.37) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, S.; Zhang, L.; Hou, C.; Han, Y. Internet Use, Subjective Well-Being, and Environmentally Friendly Practices in Rural China: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410925

Lei S, Zhang L, Hou C, Han Y. Internet Use, Subjective Well-Being, and Environmentally Friendly Practices in Rural China: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410925

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Shuo, Lu Zhang, Chunfei Hou, and Yongwei Han. 2023. "Internet Use, Subjective Well-Being, and Environmentally Friendly Practices in Rural China: An Empirical Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410925

APA StyleLei, S., Zhang, L., Hou, C., & Han, Y. (2023). Internet Use, Subjective Well-Being, and Environmentally Friendly Practices in Rural China: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability, 15(14), 10925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410925