1. Introduction

Income diversification has a significant influence on the socio-economic wellbeing of individuals living households, especially at the microeconomic level (Mohammed, 2018) [

1]. For example, in “Happiness: A lesson from new sciences”, Richard Layard said that the incomes of the developed world increase at a faster rate than the corresponding increase in life satisfaction (Layard, 2006) [

2]. However, there are number of studies suggesting that the happiness scores of wealthier countries are comparatively higher than those of poorer countries. Income diversification allows these countries’ citizens to reduce their risk of income depletion due to natural calamities causing losses in agricultural produce while enhancing consumption, including the access to good education for children, and allowing them to cover expenses related to health; these expenses are critical in terms of quality of life (Sultana, N., Hossain, E., Islam, K., 2015) [

3]. The diversification of income is measured in terms of trade-offs of capital assets and strategies that rural farmers command in order to maximize utility for better wellbeing (Sultana, N., Hossain, E., Islam, K., 2015) [

3].

Senevirthna and Dharmadasa (2021) [

4] argued that income diversification is globally considered as an effective way to significantly reduce income risks and support improved household wellbeing in developing countries (Senevirathna, M. and Dharmadasa, R., 2021) [

4]. For instance, more that 65% of the total workforce of less-developed countries is engaged in multiple occupations in order to reduce poverty, achieve income and consumption stability, and facilitate the overall improvement of the quality of life or wellbeing of household occupants (Minot, N., Epprecht, M., Anh, T. and Trung, L.Q., 2006) [

5]. The study conducted by Salam, S., et al. (2019) [

6] indicated that an appropriate method of reducing poverty and improving household wellbeing is the diversification of rural livelihoods (Salam, S., Bauer, S. and Palash, S., 2019) [

6]. A similar report released by the IFAD (2011) [

7] revealed that the majority of the occupants of rural households have engaged in off-farm activities in the last few decades; this allows them to earn more additional income to help improve their living standards (IFAD, 2011) [

7].

According to Joshi et al. (2003) [

8], income diversification refers to an increase in number of sources of incomes. It includes switching from low-value crop production to high-value crop production and non-farm activities (Joshi, P.K., Gulati, A.A., Birthal, P.P. and Twari, L., 2003) [

8]. Income from agriculture includes income from crops, livestock, fisheries, and forestry, while non-agricultural income includes both off-farm wage labor and non-farm self-employment (Sultana, N., Hossain, E., Islam, K., 2015) [

3]. Income diversification is the adjustment of farming, which combines various and complimentary agricultural activities and moves agricultural resources from low to higher value (Seng, 2014) [

9].

O’Neil (2021) [

10] stressed that the income diversification of rural countries, especially Cambodia, is considered to stem from rice production and self-employment such as working in garment factories, services, and other fields (O’Neill, 2021) [

10]. Some farmers earn low incomes due to low agricultural output, thereby increasing the incidence of poverty (Bojnec, S.; Knific, K., 2021) [

11]. As a result, the diversification of income is one among several indicators defining the attainment of objective wellbeing and life goals. Rural households command ranges of ‘capital assets’ that can be considered to act as portfolios, such as good environmental resources, and good social relations that act as human capital, allowing them to diversify their investments to broad ranges of activities to improve wellbeing (Gautam, Y. and Andersen, P., 2015) [

12].

The majority of rural farmers in developing countries obtain their income from agriculture (Bojnec, S.; Knific, K., 2021) [

11]. According to Joshi et al. (2003) [

8], income diversification refers to an increase in a number of different sources of income. The sources of income diversification can be defined as a process of switching from low-value crop production to high-value crop production and non-farm activities (Joshi, P.K., Gulati, A.A., Birthal, P.P. and Twari, L., 2003) [

8]. Income diversification can be divided into non-crop agricultural income, such as livestock, fisheries, and forestry, and non-agricultural income, which includes both off-farm wage labor and non-farm self-employment (Sultana, N., Hossain, E., Islam, K., 2015) [

3]. Income diversification is the most remarkable characteristic of rural livelihoods that can be linked to wellbeing, but rural families also construct portfolios of aspects such as good environmental resources and good social relations in supporting capacities (Gautam, Y. and Andersen, P., 2015) [

12].

It is clear that increases in income satisfy the objective wellbeing of farmers (Chan, S. and Acharya, S., 2002) [

13]. In short, academics and policy makers agree that income diversification is a determinant factor of the subjective wellbeing of people in both developed and developing countries (Mohammed, 2018) [

1]. The World Bank has indicated that over 60% of the Cambodian population had increased their income by the end of the 2000s due to increases in job diversification and an increase in agricultural production, mainly rice production; thus, occupational shifting allowed most rural farmers to increase their income generation to support quality of life and sustainable livelihoods (World Bank, 2015) [

14].

Most farmers in the farming communities of Tang Krasang and Trapang Trabek have been involved in income diversification from different sources. The sources of income are diverse, ranging from rice production to off-farm employment and migration. The improvement of the physical infrastructures of rural communities, the intensification of rice production, and an increase in the use of marketing and technologies result in large numbers of farmer households being capable of increasing their incomes. In this context, we seek to understand how the goal attainment of farmers is shaped by objective conditions, particularly income diversification. Through increased income diversification, a large proportion of household farmers in the analyzed communities have improved these rural areas’ physical infrastructures, and the intensification of rice production has sustained their livelihoods. Income diversification has had a positive impact on the wellbeing of household farmers and improved the quality-of-life goals of household farmers in communities (Seng, 2014) [

9].

There is a significant relationship between income diversification and household wellbeing. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to identify whether the diversification of income affects household wellbeing, specifically with respect to whether life goals are impacted by the incomes of the households’ occupants. Three models of life goals analyzed in a regression model are employed to measure farmer household wellbeing. Household wellbeing in this context refers to farmers having derived satisfactory income from diversified occupations. No research on income diversification and life goal connectivity has been conducted yet.

2. Literature Review

Income diversification impacts wellbeing among household occupants and its potential to reduce poverty levels (Mohammed, 2018) [

1]. The survival of the occupants of any household or group of households primarily depends on the level of the occupants’ wellbeing with respect to facets such as food, clothes, education, health, and other assets, which must be affordable, i.e., available at a price within the income scope of the household (Mohammed, 2018) [

1]. Income diversification has been shown to be positively associated with wealth accumulation and reduced vulnerability. However, little is known about how income diversification may protect households against exogenous shocks in less-developed countries. In this context, it is unclear how income affects quality of life in Cambodia (Kimsun, T. and Sokcheng, P., 2013) [

15].

Income can be diversified either ex ante or ex post to manage the risk of shocks (Kimsun, T. and Sokcheng, P., 2013) [

15]. These risks include response to household shocks, risk reduction, asset accumulation strategies, and wellbeing (Kimsun, T. and Sokcheng, P., 2013) [

15]. Wellbeing can be measured in terms of household income. Therefore, the terms of diversification can be implemented as accumulation and survival factors. As a result, regarding the diversification of income, it can be found that richer households have a greater ability to diversify their sources of income than poorer households. In this context, household occupants’ wellbeing can be clustered into different types between the marginalization of households and richer households (Kimsun, T. and Sokcheng, P., 2013) [

15].

Senevirathna et al. (2021) [

4] indicated income diversification can be subject to uncertainty due to political instability. However, when social security is stable, farmers have a greater chance of increasing their incomes from the diversification of jobs in order to improve their wellbeing and ability to achieve life goals (Senevirathna, M. and Dharmadasa, R., 2021) [

4]. In addition, the research study conducted by Kassie, G.W., et al. (2017) [

16] argued that off-farm self-employment is an incentive for farmers to consider the expansion of their range of income sources through an increase in return from off-farm activities. As a result, in the less-developed world, especially Asia, a greater number of farm households supplement their labor with off-farm income generation activities in order to reduce income risk/shocks and food security by diversifying their sources of income (Kassie, G.W., Kim, S. and Fellizar, F.P., 2017) [

16].

It has been observed that off-farm diversification decisions are mostly driven by household aspects ranging from good health, education, and household age composition to subjective wellbeing, allowing farmers to obtain satisfactory sources of income (Kassie, G.W., Kim, S. and Fellizar, F.P., 2017) [

16]. As presented in the results of their research study on Cambodia, Chan, S. et al. (2002) [

13] found that household income derived from different sources in rice-farming and poor rural communities. Most farmers started to diversify their income generation activities by adopting wage labor due to the declining availability of common resources in order to maintain household wellbeing (Chan, S. and S, Acharya, 2002) [

13]. The cited study showed that the role of income diversification was crucial for household wellbeing during the Global Financial Crisis (Chan, S. and S, Acharya, 2002) [

13].

Bojnec, S.; Knific, K., (2021) [

11] argued that the diversification of income from self-employment is important so that households can maintain food production for the market and a main source of income to maintain household wellbeing. (Bojnec, S.; Knific, K., 2021) [

11]. Kelly (2011) [

17] contended that the reorganization of the importance of off-farm variables such as gender, age, and family structure allows farmers to invest remittance income into improving their farming practices and wellbeing (Kelly, 2011) [

17]. Fox, F, et al. (2018) [

18] revealed that agricultural intensification allowed for the maintenance of output levels with less family labor. Remittances enable the hiring of off-farm laborers and agricultural inputs to increase income for the wellbeing of farmers in communities (Fox, F., Nghiem, T., Kimkong, H., Hurni, K., and Baird, Ian, 2018) [

18].

Hoeur (2018) [

19] found that among the adolescent waste pickers in Phnom Penh, life goals and the components of subjective wellbeing include a complete family, being loved and cared for, a sense of meaning in life, receiving support, the enjoyment of life, a sense of belonging, being accepted and understood, the acceptance of reality, a sense of satisfaction in life, and the enjoyment of being healthy and free from worries (Hoeur, 2018) [

19]. In a similar vein, Beauchamp, Woodhouse, Clements, and Milner-Gulland (2018) [

20] studied household famers’ wellbeing and income diversification in a conservation context in Cambodia based on local conceptions. Household farmers’ wellbeing and income diversification domains were identified as agricultural land, food security, health services, income generation, natural resources, houses, agricultural materials (Beauchamp, E., Woodhouse, T. Clements, and Milner-Gulland, 2018) [

20].

As revealed in regional approaches, it has been shown that most Indonesian rural households have adapted to socioeconomic and political change in order to increase their income from agricultural production and off-farm activities. The form of adaptation to the changes brought by globalization among rural households has been to grow many kinds of more marketable crops to diversify agricultural income (Kuroyanagi, 2007) [

21]. Nadya Karimasari (2014) [

22] contended that in the context of Thailand, off-farm activities and migration tend to draw individuals from rural areas into urban areas in order to livelihoods in industries as diverse as the construction industry, manual labor, and even marketing, but none are providing sustainable and reliable sources of livelihood; thus, the affected individuals migrate back to rural areas (Karamasari, 2014) [

22].

Hue, V (2011) [

23] explained that the majority of villagers in Man Xa, Red River Delta, Vietnam, do not earn income from the sale of agricultural products and livestock to support their wellbeing. In contract, most of them earned income from high-return-on-income diversification such an aluminum and metal melting and trading (Van Hue, 2011) [

23]. In some countries in Southeast Asia and Europe, the largest source of household income and the largest proportion of a nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are derived from diversified sources such as urbanized jobs, industrialized jobs, and market-based incomes (Fox, F., Nghiem, T., Kimkong, H., Hurni, K., and Baird, Ian, 2018) [

18]. In contrast, the income from agriculture is not sufficient for household consumption and expenditure; thereby leading to the reorganization of the importance of diversification with respect to aspects such as gender, age, and family structure (Kelly, 2011) [

17].

Global approaches have shown that income diversification and household farmer wellbeing and life goals have been growing, partly in response to the inadequacy of the use of economic proxies in policy circles. In this global perspective, the term ‘development’ is commonly used, representing a shift from the term economic growth; this was implemented to encompass more holistic indicators and provide a better characterization of quality of life (Ravallion, M, 2023) [

24]. It has been stated that wellbeing can be categorized as material wellbeing and social wellbeing. Material wellbeing consists of one’s state of mind and appearance. Social wellbeing is caring for children, self-respect, peace, and love in the family and the community (Narayan D., Chambers R., Shah M.K., 2015) [

25]. Research in Vietnam has shown that farmers in the Mekong Delta area that have diversified from rice growing have improved their wellbeing significantly (Markussen, T., Fibak, M., Tarp, F., Tuan, N., 2017) [

26].

Lansing, D. et al. (2007) [

27] explained that the combination of on-farm and off-farm labor of rural households enhances their income toward achieving sustainable, diversified livelihoods (Lansing, D., Bidegaray, P., Hansen, D., McSweeney, 2007) [

27]. Mohammed (2018) [

1] stressed that the diversification of income reduces income risks and provides an improvement in sustainability in comparison to the less-diversified livelihoods (Mohammed, 2018) [

1]. Household farmers’ wellbeing is measured in terms of household income because income is a significant means of purchasing power that enables the attainment of high living standards and the sustainable livelihood of rural farmers (Doyal and Gough, 1994) [

28]. Saxby, H. et al. (2019) [

29] stated that in advanced counties, life satisfaction, income diversification, and quality of life are measured in terms of political stability, social aspects, and household individual happiness (Saxby, H., Gkartzios, M. and Scott, K., 2019) [

29]. Rural public goods are especially important with respect to rural farmers’ ability to realize rural sustainability and prosperity and improving wellbeing (Li, L., Zhang, Zh, and Fu, Ch., 2020) [

30].

Income diversification significantly contributes to family income, having an effect on the variety of food consumed by rural families of different sizes (ul Haq, S., Boz, I., Shahbaz, P., and Ramiz Murtaza, M., 2020) [

31]. Income diversification has been qualitatively defined as encompassing good standards of living, good health, and good quality of life in terms of rural farmers’ sustainability from different perspectives (Stiglitz, J.E., Amartya, S., and Fitoussi, J., 2009) [

32]. Rural household farmers’ wellbeing is measured in terms of household income diversification. This measurement consists of asking farmers about their livelihoods and living conditions with respect to the resources available that allow them to live with satisfaction and happiness. People’s ideas and experiences regarding their daily life activities and feelings regarding income diversification, household assets, and availability of resources can be connected to their wellbeing and life goals (Stiglitz, J.E., Amartya, S., and Fitoussi, J., 2009) [

32]. According to Diener and Suh (1997) [

33], household wellbeing is measured through verification in society. Therefore, it includes death ratios, birth rates, health, happiness, rates of social violation, and forms of punishment (Diener, E. and E. Suh., 1997) [

33].

Wellbeing is an area of contention among academics. In policy circles, the concept of human wellbeing is conflated with the concept of ‘poverty’. However, objective criteria, particularly those associated with economic proxies, are always considered as determinant factors, while subjective wellbeing, such as satisfaction and happiness, is considered too variable when compared to objective wellbeing. As a result, ‘economic growth’ is also regarded as a top priority in development, and this idea has long been criticized. The Research Group on Wellbeing in Developing Countries (WeD), coordinated by Bath University, UK, contended that relationships between subjective and objective conditions could transcend those defined by standard economics and policy makers.

Analytical Conceptual Framework

According to (Mohammed, 2018) [

1], income diversification is a potential method of reducing income risk. A result from the cited study revealed that in less-developed countries, especially those in Asia, more than 60% of the total workforce engages in job diversification in order to reduce household food shortages and income inequality and secure improvements in the standard of living of farm households and household wellbeing. Essentially, wellbeing refers good quality of life (Minot, N., Epprecht, M., Anh, T.T.T. and Trung, L.Q., 2006) [

5].

Income diversification is positively correlated with household wellbeing, which implies farmers who have an alternative source of income are more capable of catering to the food and non-farm requirements of their households. Both non-farm and farming activities play a significant role in the wellbeing that determines a household’s success (Gautam, Y. and Andersen, P., 2015) [

12]. Households with more diversified income sources tend to rely on lower levels of consumer welfare, indicating that diversification mainly occurs due to push factors (Khan, R. and Morrissey, O., 2019) [

34]. Household wellbeing is not always directly affected by income diversification alone; it can also be the case that those with a more diversified income base are better resistant to policy changes and weather shocks (Ersado, 2006) [

35]. The framework presented herein will also explore the impact of income diversification on household wellbeing, which will be examined in terms of not only the income sources from non-farm employment but also livelihood portfolios in the high-return sector (Khan, R. and Morrissey, O., 2019) [

34].

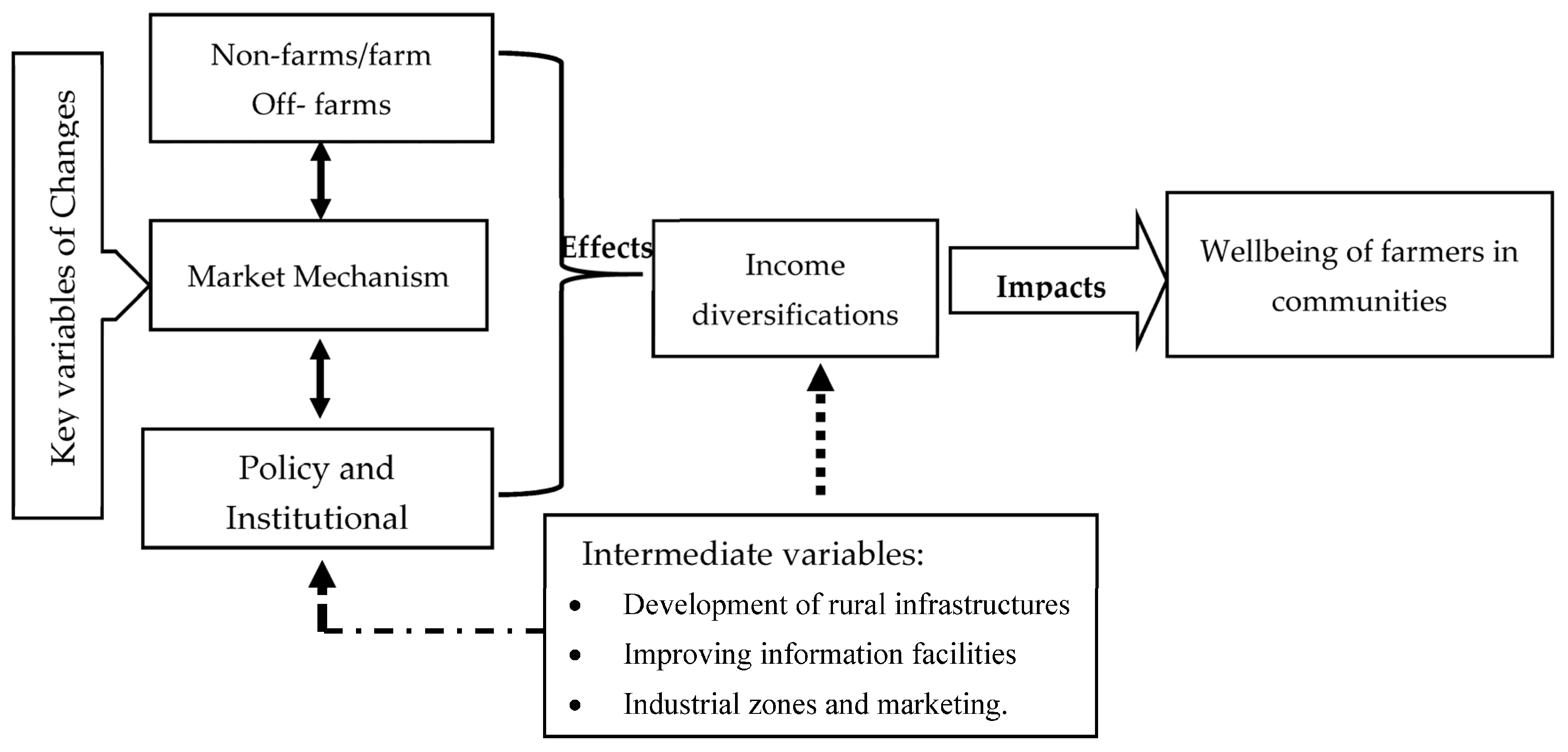

The diagram identifies key variables of changes to three non-farm and off-farm components, namely, agricultural market mechanisms and policy and institutional support. In addition, there are indirect immediate variables, including the development of rural infrastructure, information facilities, and industrial zones and marketing. Off-farm work contributes to household food security and improves household wellbeing by providing cash for food, other household purchases, and the acquisition of agricultural assets. Therefore, it is clear that off-farm work income diversification is a way of reducing income variability (Nsikan E.B., Damian, A., Mfon, E. and Edet, 2016) [

36].

Through these premises, we investigate the drivers and processes that effect income diversification and its impact on household wellbeing at the local level. Our analytical approach examines how these processes reveal economic challenges and livelihood risks and benefits at the household level, including access to the market and changes in income and support from policy and institutions targeting farmers. From the construction theories presented in the literature review above, this study draws an analytical framework of income diversification and household wellbeing in rice-farming communities. The framework demonstrates the structures of the factors driving the income diversification of rural farmers that have a significant impact on their wellbeing (as presented in

Figure 1). In the

Figure 1 below, we investigate the way in which the relationship between these drivers of income diversification influence household wellbeing among farmers in the communities of Stung Chreybak.

4. Results

4.1. Household Labor Division for Income Diversification

Figure 3 shows the household labor division amongst men and women in the six study villages. Farmers mentioned that the household-level diversification of income sources was important, wherein they prioritized diversification from non- and off-farm activities. We surveyed a total of

n = 300 households, and it was observed that the number of household members amongst families ranged from three to four people. Women were more involved in diversification with respect to non-agricultural jobs, such as house-work, taking care of children, and garment work, as depicted by the yellow line. About 89% of women aged between 18 and 35 years old generated diversified income for their respective households via off-farm employment through working at garment factories and oversee migration, while men were involved in on-farm agriculture. About 11% of young men were able to continue their studies through higher education. Women contributed their income from off-farm employment to support their living and purchase agricultural inputs.

4.2. Diversification of Income of Households in the Analyzed Communities

The income of the farmers in the analyzed communities derived from different sources, such as non-farm, on-farm, and off-farm activities. About 50% of the income of the farmers in the analyzed households in less-developed countries stemmed from a non-farm source (Gautam, Y. and Andersen, P., 2015) [

12]. For example, income diversification can provide sustainable livelihood for farmers in communities via the expansion of dry season rice paddies, access to higher education, access to good health care, and the upgrading of houses.

The total incomes of the households were significantly higher after the improvement of rural physical infrastructures and facilities.

Labor markets in less-developed countries are often viewed as ‘segmented’ in the sense that there are exogenous barriers to movement from one sector to another (Markussen, Fibak Tarp, and Tuan, 2017) [

26]. This study shows that at present, most farmers experience barriers regarding labor forces, which have been inferred from large income differences across sectors (Field, 2021).

Figure 4 indicates the three main characteristics of the incomes derived from the household respondents in terms of percentages for the six villages in the study area. The sample size of the household questionnaires from the six villages shows that farmers acquired income from different sources, including from on-farm, non-farm, and off-farm activities.

On-farm sources of income refers to sources of income that farmers have received from the sale of their rice yields, especially dry-season rice yields. On-farm sources of income accounted for 36%, making it the second greatest source of income for a household’s wellbeing improvement and livelihood optimization. The non-farm sources of income were defined by farmers as the sources of income gained through different activities, including the harvesting of non-timber forest products, animal husbandry, home gardening, and fishing. These sources account for 15% of the total and are considered an additional source of income for the farmers. About 49% of the total source of income obtained from off-farm employment was considered ‘satisfactory’. Off-farm activities included construction, employment in garment factories, overseas migration, the reception of loans from microfinance institutions, and the reception of cash from relatives. From among these sources of income, almost half of the farmers obtained income from working at garment factories. Garment factories hire more young agricultural laborers, who, in turn, provide wages to supplement agricultural livelihoods. In the interviews, 98% of the respondents in the villages related that off-farm income was such a large proportion of their income that it contributed to the wellbeing of the farmers and their agricultural input.

4.3. Regression Analysis Results

We used three regression models of life goals: (1) model 1, which concerned external life goals, represented by “Y1”; (2) model 2, which concerned internal life goals, represented by (Y2) and (3); and model 3, which concerned relational life goals, represented by (Y3). The reason that we used three models separately to analyze the relationship between the key research finding factors and subjective wellbeing and life goals is because each model has multiple independent variables so that it can be regressed, resulting in separate units.

This model consists of a regression analysis of the relationship between influencing factors and household wellbeing with respect to “external life goals”

Table 2. The results of the regression performed using model 1 are as follows: R (0.628a), R Square (0.394), and Std. (1.93247) for agricultural income (X1), non-agricultural income (X2), combined income ratios (X3), income from rice (X4), consumption expenses (X6), cultural expenses (X7), size of land (X8), household debt (X9), investment in agriculture (X10), shortage of water (X12), solved by department (X14), solved by NGOs (X15), and solved by others (X17).

For household capital assets, one unit increase in consumption expenses (X6) dramatically decreased external life goals (p < 0.05) by 69.2%. In contrast, with an increase in cultural expenses (X7) and household debt (X9), the external life goals increased by about 41.8% and 29% (p < 0.05), respectively. The table shows that only one factor, solved by others (X17), influenced the external life goals; with an increase in this factor, the external life goals decreased by 60% (p < 0.05).

The results of the second regression model correspond to internal life goals (Y2). The model yielded R 0.649a, where R Square is 0.422 and Std. 2.02225. a. Predictors: (Constant), Solved by others (X17), Cultural expenses (X7), Non-agricultural income (X2), Solved by NGOs (X15), Income from rice (X4), Solved by department (X14), Household debt (X9), Size of land (X8), Investment in agriculture (X10), Agricultural income (X1), Shortage of water (X12), Both income ratios (X3), and Consumption expenses (X6).

Table 3 clearly indicates that the internal life goals are explained by market integration, household capital assets, agricultural technologies, and institutional and policy processes. It has been noticed that when the factor of market integration presented a one-unit increase in both agricultural income (X1) and non-agricultural income ratios (X3), this increased internal life goals by 30% (

p < 0.05), while a one-unit increase in income from rice (X4) decreased internal life goals by 55.2% (

p < 0.05). For household capital assets, cultural expenses (X7) negatively influenced the internal life goals, where a one-unit increase in cultural expenses decreased internal life goals by 26.7% (

p < 0.05). However, internal life goals increased with an increase in the size of land (X8) by 41.4% (

p < 0.05).

The results of regression model 3 concern relational life goals (Y3). The model yielded an R value of 0.630a, an R square of 0.307, and adjusted R square of 0.347, and an Std. of 1.29344. The corresponding predictors are as follows: (Constant), Solved by Others (X17), Cultural expenses (X7), Non-agricultural income (X2), Solved by NGOs (X15), Income from rice (X4), Solved by Department (X14), Household debt (X9), Size of land (X8), Investment in agriculture (X10), Agricultural income (X1), Shortage of water (X12), Both income ratios (X3), and Consumption expenses (X6).

As shown in

Table 4, relational life goals were explained by market integration, household assets, and institutional and policy processes. For market integration, a one-unit increase in agricultural income (X1) significantly increased the relational life goals by approximately 56% (

p < 0.05), while a one-unit increase in non-agricultural income (X2) and both agricultural and non-agricultural income ratios (X3) decreased relational life goals by 23.8% and 70.7%, respectively (

p < 0.05). For household capital assets, a one-unit increase in size of land (X8) decreased relational life goals (

p < 0.05) by 30.1%, while with an increase in problems solved by Department (X14) in the institutional and policy processes, relational life goals increased by about 32.4% (

p < 0.05).

5. Discussion

The sources of household income are diverse, stemming from, e.g., on-farm activities and off-farm employment, providing essential support for the wellbeing of a household. When the diversification and transformation of income-generating activities from agricultural production decrease, self-employment and labor rise significantly (Chan, S. and S., Acharya, 2002) [

13]. According to Gautam et al. (2015) [

12], when farmers are well prepared with respect to their livelihood portfolios through income diversification, this enhances the wellbeing of farmer households (Gautam, Y. and Andersen, P., 2015) [

12].

We found that most of the farmers have diversified their income as a key strategic approach to earning income, reducing poverty, and ensuring sustainable livelihoods and food security. The diversification of income can support household wellbeing and life goals. However, it leads to diminishing returns and strain within relationships, resulting in a less-enjoyable job (Diener, E., & Seligman, M.E.P., 2004) [

37]. It is evident that income diversification is a useful means of improving rural farmer household wellbeing in our study area. Over time, it is likely that the relative importance of the off-farm sector will increase further. Broad-based rural income growth requires that the poor and disadvantaged will also be able to benefit from this structural change. Improved opportunities in rural areas could also help reduce the massive level of rural–urban migration with its concomitant development problems (Bongole, 2016) [

38]. Thus, we argue that local institutions that are well connected and powerful bodies capable of pushing and creating greater diversification of jobs to obtain higher returns and generate income are crucial in enabling farmers to improve their quality of life and wellbeing.

The results show that rice-farming communities make a good living and have access to health care and good schools for higher education, and social networks and cultural exchanges have been measured via income diversification (Stiglitz, J.E., Amartya, S., and Fitoussi, J., 2009) [

32]. Rural households’ wellbeing is measured in terms of income diversification. Income diversification is significantly related to the key factors of weather conditions, crop failure, and instability, which, in turn, precipitate a sharp decrease in farm income. Additionally, it provides growing opportunities to create additional sources of income to help improve household wellbeing significantly (Senevirathna, M. and Dharmadasa, R., 2021) [

4]. In this context, the wellbeing of many farmers in rice-farming communities in Tang Krasang and Trapang Trabek has been improved through the change from having a single source of employment to engaging in diverse forms of employment to enable the commercialization of their products through the markets.

Access to local institutions and policies for the creation of job opportunities is limited, posing some difficulties for farmers consisting of a loss of confidence and a high risk of diversified livelihoods and unsustainability (Bojnec, S.; Knific, K., 2021) [

11]. According to this study, most farmers associate a high income with an increase in life satisfaction. In this respect, their external life goals were highly valued with respect to enhancing wellbeing. Later, development and change in wider socio-economic aspects are more related to the delivery of materialistic needs to rural people.

Thus, the above findings constitute an important explanation of why internal and relational life goals’ importance directly affect the wellbeing of household-dwelling farmers in rural communities since the last decade (Promphakping, B., et al. 2021) [

39]. In relation to this, the results from the regression model analysis revealed a coefficient of 32.4%, showing that for an increase in support provided to the source of income, the wellbeing of the household increased by 0.324 units (

p < 0.05). Therefore, as in

Table 2, it has been presented that the coefficient of income diversification is positive. The value of the coefficient of agricultural income (X1) is 63.9% (

p < 0.05), which is linked to achieving significant life goals. As a result, it can be used to predict whether farmers are satisfied with their life goals and happy with their income from agriculture.