Enhancing Shoppers’ Experiences and Building Mall Loyalty: The Role of Octomodal Mental Imagery (OMI) and Management Dimension-Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region of China

Abstract

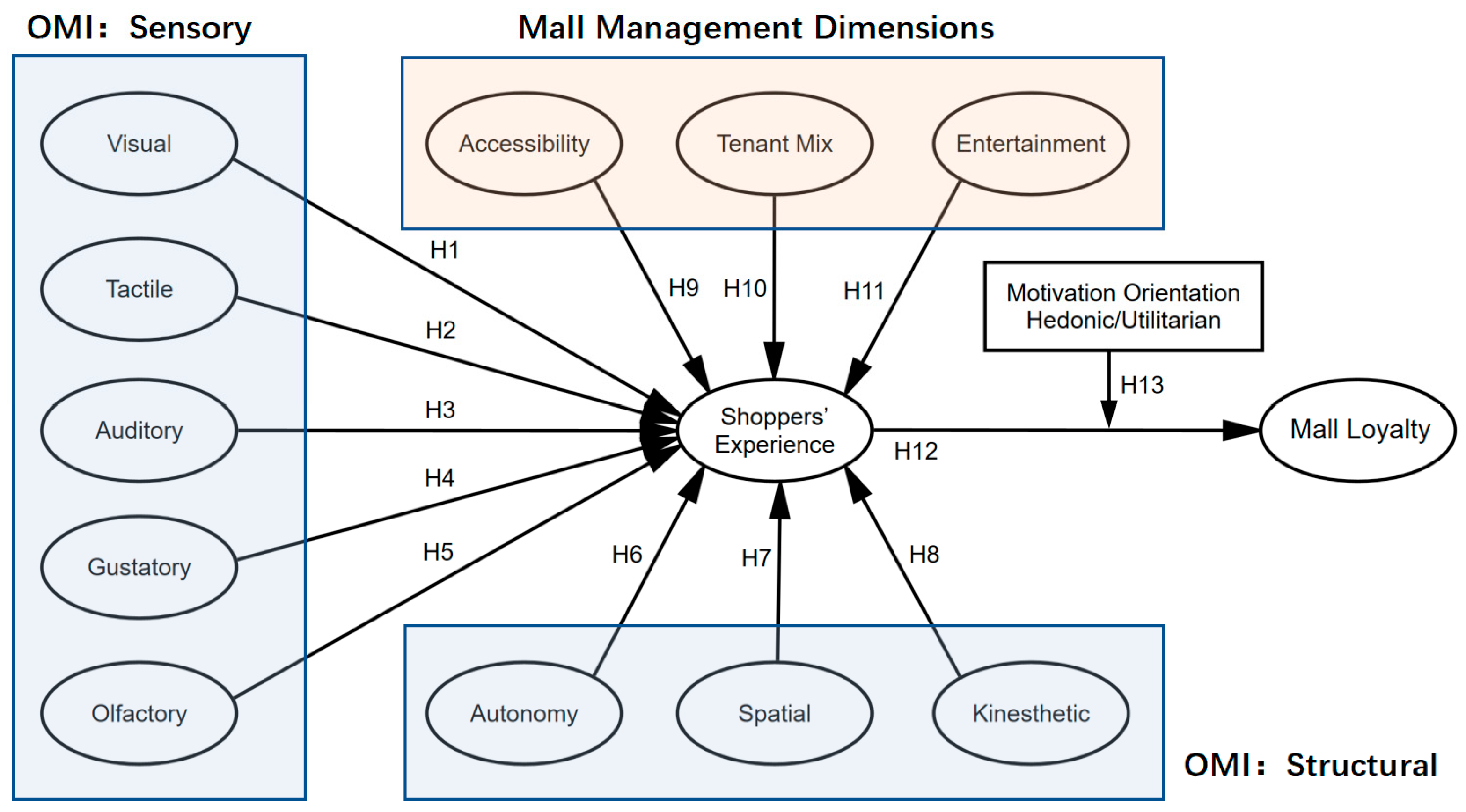

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Octomodal Mental Imagery (OMI)

2.2. Mall Management Dimensions

2.2.1. Accessibility

2.2.2. Tenant Mix

2.2.3. Entertainment

2.3. Shoppers’ Experience

2.4. Mall Loyalty

2.5. Motivation Orientation

2.6. Theoretical Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Development of Research Instruments

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Research Application Used

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Reliability Analysis

4.3. Normality Testing

4.4. Common Method Bias Test

4.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.5.1. Convergent Validity

4.5.2. Discriminant Validity

4.5.3. Model Fit

4.5.4. Pearson Correlation

4.6. Structural Equation Modelling

4.7. Moderating Role 0f Motivation Orientation

5. Discussion

- Previous studies have focused on the sensory experience of the shopping process. In contrast, the present study’s OMI emphasizes the consumer’s reliance on imagining tasting previous experiences after returning from shopping [28,29], evaluating the reconstruction of shopping experiences that occurred in the past (imagination) and expectations of future experiences [26]. This may be an important reason for the insignificance of the auditory-to-shopping experience in OMI.

- Interference of multisensory stimuli: In the shopping environment, in addition to auditory stimuli, there are multiple sensory stimuli, such as visual, tactile, and olfactory stimuli. These stimuli may compete, leading to distraction, reduced attention to, and reduced memory of auditory stimuli. Therefore, the memory effect of auditory stimuli may need improvement.

- Psychological adaptation effect: Shoppers may gradually adapt to the sounds in the shopping environment, seeing them as the norm and no longer making them an essential part of the shopper’s experience. This psychological adaptation effect may decrease shoppers’ perceptions of auditory influence, thus making the relationship between auditory and shoppers’ experiences insignificant.

- The effect of information overload: Shopping malls are often filled with various sound sources, such as music, advertisements, and shouts from salespeople. This large number of sound stimuli may lead to a perceptual information overload for shoppers, making it difficult for them to associate specific sounds with the shopper experience. Thus, despite its presence in the shopping environment, auditory perception does not significantly impact shoppers’ subjective perceptions.

- The frequent use of headphones (listening to music to make phone porridge) by young people while shopping may also contribute to the insignificance of auditory to shoppers’ experiences in OMI.

6. Conclusions & Limitation

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Significance

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Lévy-Mangín, J.-P. Pull Factors of the Shopping Malls: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P.P.C. Shopping Centres in Decline: Analysis of Demalling in Lisbon. Cities 2019, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.B.; Dobbelstein, T.; Corbishley, K.M. A Comparative Investigation into the Changing Use of Shopping Malls in Germany and South Africa. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Brief History of the “Decline” of Shopping Centers. Available online: http://cj.sina.com.cn/article/detail/2398774943/476417 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- The 140,000-Word, 222-Page “2022 China Shopping Center Annual Development Report” Is Here! Available online: http://news.winshang.com/html/070/2339.html (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Rigby, D. The Future of Shopping. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X. Impact of Online Shopping on Shopping Malls. Appl. Econ. Theses 2018, 29. Available online: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses/29 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Helm, S.; Kim, S.H.; Van Riper, S. Navigating the ‘Retail Apocalypse’: A Framework of Consumer Evaluations of the New Retail Landscape. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R. The Death of the American Mall and the Rebirth of Public Space. In Proceedings of the International, Seattle, WA, USA, 8–11 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, M.L. The Shopping Mall of the Customer Experience Future. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, SAGE Publications Sage CA, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2015; Volume 59, pp. 1127–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. The Transition of Shopping Mall Development. 2015. Available online: https://repository.tcu.edu/handle/116099117/10443 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Babin, B.J.; Feng, C.; Borges, A. As the Wheel Turns toward the Future of Retailing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.M.; Paula, F. Shopping Mall Image: Systematic Review of 40 Years of Research. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmashhara, M.G.; Soares, A.M. Entertain Me, I’ll Stay Longer! The Influence of Types of Entertainment on Mall Shoppers’ Emotions and Behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanburn, J. The Death and Life of the Shopping Mall. Time 2017, 190, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Haytko, D.L.; Baker, J. It’s All at the Mall: Exploring Adolescent Girls’ Experiences. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, E.M.; Orozco-Gómez, M. A Segmentation Study of Mexican Consumers Based on Shopping Centre Attractiveness. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Prashar, S. Anatomy of Shopping Experience for Malls in Mumbai: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Sahay, V. Determinants of Shopping Experience: Exploring the Mall Shoppers of National Capital Region (NCR) of India. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, I.; Ahmed, S.; Sobhani, F.A.; Islam, M.A.; Sahel, S. The Influence of Mall Management Dimensions on Perceived Experience and Patronage Intentions in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, S.; Singh, H.; Parsad, C.; Vijay, T.S. Predicting Indian Shoppers’ Malls Loyalty Behaviour. Vikalpa J. Decis. Mak. 2017, 42, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J.; Pizam, A.; Fyall, A.; Tasci, A.D.A.; Hancock, P.A. Destination Imagination: Development of the Octomodal Mental Imagery (OMI) Scale. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 45, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. How to Design and Create an Effective Survey/Questionnaire; A Step by Step Guide. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, R.S.; Krishna, A. A Review of Sensory Imagery for Consumer Psychology. J. Consum. Psychol. 2022, 32, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendler, T.S. Intuition, Imagination, and Philosophical Methodology; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 0-19-100229-1. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N.J.T. Supplement to Mental Imagery. European Responses: Jaensch, Freud, and Gestalt Psychology. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; The Metaphysics Research Lab: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.; Scott, N.; Lohmann, G. Applying Experiential Marketing in Selling Tourism Dreams. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; Cao, D.; Jiang, M.; DeLacy, T. Savouring Tourist Experiences after a Holiday. Leisure/Loisir 2013, 37, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, Z.; Wyer, R.S. Slowing Down in the Good Old Days: The Effect of Nostalgia on Consumer Patience. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. The Imagination of Place and Tourism Consumption: A Case Study of Lijiang Ancient Town, China. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Lehto, X.; Wei, W. The Hedonic Value of Hospitality Consumption: Evidence From Spring Break Experiences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiv, B.; Huber, J. The Impact of Anticipating Satisfaction on Consumer Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J.-C.; Sirgy, M.J.; Grzeskowiak, S. How Can Shopping Mall Management Best Capture Mall Image? J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.M.K. Attractiveness Factors Influencing Shoppers’ Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Word of Mouth: An Empirical Investigation of Saudi Arabia Shopping Malls. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2012, 3, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anselmsson, J. Effects of Shopping Centre Re-Investments and Improvements on Sales and Visit Growth. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkin, C.D.; Lord, J.D. Attraction of Power Shopping Centres. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 1997, 7, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raajpoot, N.A.; Sharma, A.; Chebat, J.-C. The Role of Gender and Work Status in Shopping Center Patronage. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok Kim Man, M.; Cai Qian Qiu, R. An Empirical Study of Factors Influencing Consumers’ Purchasing Behaviours in Shopping Malls. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2021, 13, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arentze, T.A.; Oppewal, H.; Timmermans, H.J.P. A Multipurpose Shopping Trip Model to Assess Retail Agglomeration Effects. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, E.; Lim, A.; Xu, J. Retail Store Layout Optimization for Maximum Product Visibility. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2022, 74, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M.I.; Eid, R. Measuring the Perceived Value of Malls in a Non-Western Context: The Case of the UAE. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkup, M.; Rafiq, M. Managing Tenant Mix in New Shopping Centres. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1994, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, C.Y.; Xu, S.Y. A Tenant-mix Model for Shopping Malls. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelhas Brito, P. Shopping Centre Image Dynamics of a New Entrant. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2009, 37, 580–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S.; Vilnai-Yavetz, I.; Mitchell, V.; Borges, A.; Frimpong, K.; Belhsen, N. Mall Experiences Are Not Universal: The Moderating Roles of National Culture and Mall Industry Age. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H.; Ridgway, N.M.; Dawson, S.A. The Shopping Mall as Consumer Habitat. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, F.F.; Askegaard, S. Malls and the Orchestration of the Shopping Experience in a Historical Perspective. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1999, 26, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.A.F.; Li, F.; Kranendonk, C.J.; Roslow, S. The Seven Year Itch? Mall Shoppers across Time. J. Consum. Mark. 2002, 19, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Baker, J. Excitement at the Mall: Determinants and Effects on Shopping Response. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nisco, A.; Rosaria Napolitano, M. Entertainment Orientation of Italian Shopping Centres: Antecedents and Performance. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2006, 16, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, Y.-K. Shopping Enjoyment and Store Shopping Modes: The Moderating Influence of Chronic Time Pressure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hedhli, K.; Chebat, J.-C.; Sirgy, M.J. Shopping Well-Being at the Mall: Construct, Antecedents, and Consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, B.; Atulkar, S. Satisfaction of Mall Shoppers: A Study on Perceived Utilitarian and Hedonic Shopping Values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, J.C.; Rubio, N. Measuring Customer Experience in Physical Retail Environments. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 884–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerin, R.A.; Jain, A.; Howard, D.J. Store Shopping Experience and Consumer Price-Quality-Value Perceptions. J. Retail. 1992, 68, 376. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström, K. Understanding Recreational Shopping: A New Approach. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2006, 16, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Bagdare, S. Music and Consumption Experience: A Review. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-87584-819-2. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A. Customer Experience Management: A Critical Review of an Emerging Idea. J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.R.; Srivastava, R.K. Creating the Futuristic Retail Experience through Experiential Marketing: Is It Possible? An Exploratory Study. J. Retail Leis. Prop. 2010, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pullman, M.E.; Gross, M.A. Ability of Experience Design Elements to Elicit Emotions and Loyalty Behaviors. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Ramaseshan, B. The Customer Experience—Loyalty Link: Moderating Role of Motivation Orientation. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 31, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components that Co-create Value With the Customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahler, M.; Klein, J.F.; Paul, M. Measuring Customer Experiences: A Text-Based and Pictorial Scale. Mark. Sci. Inst. Work. Pap. Ser. Rep. 2019, 19, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, S.; Clark, M.; Samouel, P.; Hair, N. Online Customer Experience in E-Retailing: An Empirical Model of Antecedents and Outcomes. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Attaway, J.S. Atmospheric Affect as a Tool for Creating Value and Gaining Share of Customer. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Wong, K.K.-K.; Yu, H. The Effects of Mall Personality and Fashion Orientation on Shopping Value and Mall Patronage Intension. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Sparks, L. Loyalty Saturation in Retailing: Exploring the End of Retail Loyalty Cards? Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1999, 27, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zinkhan, G.M. Determinants of Retail Patronage: A Meta-Analytical Perspective. J. Retail. 2006, 82, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hedhli, K.; Chebat, J.-C. Developing and Validating a Psychometric Shopper-Based Mall Equity Measure. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Reynolds, K.E.; Arnold, M.J. Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value: Investigating Differential Effects on Retail Outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matos, C.A.; Rossi, C.A.V. Word-of-Mouth Communications in Marketing: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Antecedents and Moderators. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marona, B.; Wilk, A. Tenant Mix Structure in Shopping Centres: Some Empirical Analyses from Poland. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Triantafillidou, A.; Siomkos, G.; Papafilippaki, E. The Effects of Retail Store Characteristics on In-Store Leisure Shopping Experience. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 1034–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krey, N.; Picot-Coupey, K.; Cliquet, G. Shopping Mall Retailing: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Assessment of Chebat’s Contributions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltcheva, V.D.; Weitz, B.A. When Should a Retailer Create an Exciting Store Environment? J. Mark. 2006, 70, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.S.; Cheng, E. Assessing Tourists’ Satisfaction with Shopping in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R.; Rips, L.J.; Rasinski, K. The Psychology of Survey Response; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, S.L. Issues and Procedures in Adopting Structural Equation Modelling Technique. J. Quant. Methods 2008, 3, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An Examination of the Effects of Motivation and Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Structural Model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduful, A.K.; Eduful, M. Malls, Modernity and Consumption: Shopping Malls as New Projectors of Modernity in Accra, Ghana. J. Consum. Cult. 2022, 22, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; ISBN 0-674-26227-1. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M. Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 0-19-153403-X. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and Practice in Reporting Structural Equation Analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseki, M.I. Customer Expectations In Mall Restaurants: A Case Study. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013, 14, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Benhamza Nsairi, Z. Managing Browsing Experience in Retail Stores through Perceived Value: Implications for Retailers. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 676–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banytė, J.; Rūtelionė, A.; Jarusevičiūtė, A. Modelling of Male Shoppers Behavior in Shopping Orientation Context. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, C.; Puccinelli, N.M.; Grewal, D.; Roggeveen, A.L. Store Atmospherics: A Multisensory Perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, B.M.L. Sensory Cues as Retailing Innovations: The Case of Media Markt. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 1, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultén, B. Sensory Cues and Shoppers’ Touching Behaviour: The Case of IKEA. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Gupta, A.; Tripathi, V. Managing Shopping Experience through Mall Attractiveness Dimensions: An Experience of Indian Metro Cities. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Weitz, B.A.; Grewal, D.; Madore, M. Retailing Management; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Felker Kaufman, C. A New Look at One-stop Shopping: A TIMES Model Approach to Matching Store Hours and Shopper Schedules. J. Consum. Mark. 1996, 13, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V.S.; Koletsky, S.; Graham, J.L. A Field Study of Causal Inferences and Consumer Reaction: The View from the Airport. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Kroschke, M.; Schmitt, B.; Kraume, K.; Shankar, V. Transforming the Customer Experience Through New Technologies. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Killingsworth, M.A.; Gilovich, T. Waiting for Merlot: Anticipatory Consumption of Experiential and Material Purchases. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1924–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| OMI Test: Please close your eyes and imagine that you frequent a shopping mall and at this moment, you are relaxing and shopping in this shopping mall. Take a moment to create a detailed mental image (scene). After completing the imagery, open your eyes and select the option that best fits your mental image (from strongly disagree to agree strongly). | ||

| OMI (sensory attributes) | OMI were measured by variables adapted from [22]. (Khalilzadeh et al., 2023) | |

| Visual |

| |

| Auditory |

| |

| Tactile |

| |

| Gustatory |

| |

| Olfactory |

| |

| OMI (structural features) | ||

| Spatial |

| |

| Autonomy |

| |

| Kinesthetic |

| |

| Mall Management Dimensions | ||

| Accessibility |

| Adapted from [34] (Ahmad, 2012) |

| Tenant Mix |

| Adapted from [77] (Marona & Wilk, 2016) |

| Entertainment |

| Adapted from [34] (Ahmad, 2012) |

| Shoppers’ experience |

| Taken from [78] (Triantafillidou et al., 2017) |

| Mall loyalty |

| Taken from [79] (Krey et al., 2022) |

| Items | Categories | N | Percent (%) | Cumulative Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 170 | 47.49 | 47.49 |

| Female | 188 | 52.51 | 100.00 | |

| Age | 18–25 years old | 136 | 37.99 | 37.99 |

| 26–35 years old | 104 | 29.05 | 67.04 | |

| 36–45 years old | 99 | 27.65 | 94.69 | |

| Over 45 years old | 19 | 5.31 | 100.00 | |

| Marital status | Singleton | 193 | 53.91 | 53.91 |

| Married | 165 | 46.09 | 100.00 | |

| Educational level | Junior high school and below | 10 | 2.79 | 2.79 |

| High school and technical secondary school | 7 | 1.96 | 4.75 | |

| Junior college | 23 | 6.42 | 11.17 | |

| Undergraduate | 251 | 70.11 | 81.28 | |

| Master degree or above | 67 | 18.72 | 100.00 | |

| Average monthly income level (including bonuses, benefits and other forms of income) | 5000 and below | 160 | 44.69 | 44.69 |

| 5000–10,000 | 87 | 24.30 | 68.99 | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 65 | 18.16 | 87.15 | |

| 20,001–30,000 | 32 | 8.94 | 96.09 | |

| 30,001–50,000 | 5 | 1.40 | 97.49 | |

| 50,001 and above | 9 | 2.51 | 100.00 | |

| Total | 358 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Themes | Constructs | No. of Items | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMI (sensory attributes) | Visual | 3 | 0.831 |

| Auditory | 3 | 0.819 | |

| Tactile | 3 | 0.818 | |

| Gustatory | 2 | 0.843 | |

| Olfactory | 3 | 0.846 | |

| OMI (structural features) | Spatial | 3 | 0.841 |

| Autonomy | 4 | 0.833 | |

| Kinesthetic | 2 | 0.858 | |

| Mall Management Dimensions | Accessibility | 6 | 0.882 |

| Tenant Mix | 4 | 0.835 | |

| Entertainment | 4 | 0.851 | |

| Shoppers’ experience | Shoppers’ experience | 4 | 0.900 |

| Mall loyalty | Mall loyalty | 3 | 0.821 |

| Themes | Constructs | Items | Mean | Std. | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMI (sensory attributes) | Visual | OMI1 | 4.581 | 1.909 | −0.430 | −0.943 |

| OMI2 | 4.439 | 1.490 | −0.059 | −0.487 | ||

| OMI3 | 4.441 | 1.630 | −0.098 | −0.756 | ||

| Auditory | OMI4 | 4.690 | 1.826 | −0.567 | −0.653 | |

| OMI5 | 4.575 | 1.460 | −0.348 | −0.337 | ||

| OMI6 | 4.528 | 1.557 | −0.276 | −0.473 | ||

| Tactile | OMI7 | 4.701 | 1.906 | −0.506 | −0.877 | |

| OMI8 | 4.391 | 1.550 | −0.158 | −0.618 | ||

| OMI9 | 4.372 | 1.504 | −0.099 | −0.534 | ||

| Gustatory | OMI10 | 4.813 | 1.724 | −0.556 | −0.574 | |

| OMI11 | 4.696 | 1.493 | −0.372 | −0.540 | ||

| Olfactory | OMI12 | 4.763 | 1.780 | −0.585 | −0.622 | |

| OMI13 | 4.542 | 1.542 | −0.245 | −0.571 | ||

| OMI14 | 4.506 | 1.564 | −0.253 | −0.583 | ||

| OMI (structural features) | Spatial | OMI15 | 4.514 | 1.886 | −0.440 | −0.888 |

| OMI16 | 4.397 | 1.595 | −0.138 | −0.681 | ||

| OMI17 | 4.324 | 1.630 | −0.083 | −0.687 | ||

| Autonomy | OMI18 | 4.777 | 1.770 | −0.563 | −0.617 | |

| OMI19 | 4.419 | 1.494 | −0.129 | −0.509 | ||

| OMI20 | 4.422 | 1.508 | −0.165 | −0.504 | ||

| OMI21 | 4.570 | 1.428 | −0.153 | −0.400 | ||

| Kinesthetic | OMI22 | 4.684 | 1.830 | −0.478 | −0.872 | |

| OMI23 | 4.542 | 1.564 | −0.436 | −0.643 | ||

| Mall Management Dimensions | Accessibility | G1 | 4.802 | 1.872 | −0.599 | −0.732 |

| G2 | 4.341 | 1.540 | −0.145 | −0.649 | ||

| G3 | 4.497 | 1.533 | −0.180 | −0.751 | ||

| G4 | 4.391 | 1.515 | −0.192 | −0.407 | ||

| G5 | 4.483 | 1.504 | −0.154 | −0.430 | ||

| G6 | 4.374 | 1.532 | −0.191 | −0.418 | ||

| Tenant Mix | G7 | 4.791 | 1.810 | −0.554 | −0.729 | |

| G8 | 4.612 | 1.535 | −0.254 | −0.646 | ||

| G9 | 4.556 | 1.417 | −0.197 | −0.417 | ||

| G10 | 4.528 | 1.509 | −0.226 | −0.384 | ||

| Entertainment | G11 | 4.587 | 1.866 | −0.446 | −0.916 | |

| G12 | 4.330 | 1.582 | −0.114 | −0.615 | ||

| G13 | 4.408 | 1.578 | −0.116 | −0.772 | ||

| G14 | 4.388 | 1.644 | −0.189 | −0.723 | ||

| Shoppers’ experiences | S1 | 4.743 | 1.676 | −0.462 | −0.670 | |

| S2 | 4.578 | 1.472 | −0.316 | −0.944 | ||

| S3 | 4.612 | 1.511 | −0.375 | −0.796 | ||

| S4 | 4.534 | 1.504 | −0.410 | −0.855 | ||

| Mall loyalty | L1 | 4.612 | 1.887 | −0.488 | −0.84 | |

| L2 | 4.411 | 1.501 | −0.079 | −0.526 | ||

| L3 | 4.344 | 1.604 | −0.085 | −0.771 | ||

| Total Variance Explained | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Eigen Values | % of Variance (Initial) | % of Variance (Rotated) | ||||||

| Eigen | % of Variance | Cum. % of Variance | Eigen | % of Variance | Cum. % of Variance | Eigen | % of Variance | Cum. % of Variance | |

| 1 | 13.516 | 30.717 | 30.717 | 13.516 | 30.717 | 30.717 | 4.093 | 9.302 | 9.302 |

| 2 | 2.784 | 6.327 | 37.044 | 2.784 | 6.327 | 37.044 | 3.097 | 7.038 | 16.340 |

| 3 | 2.033 | 4.621 | 41.666 | 2.033 | 4.621 | 41.666 | 2.850 | 6.476 | 22.816 |

| 4 | 1.928 | 4.382 | 46.048 | 1.928 | 4.382 | 46.048 | 2.820 | 6.410 | 29.226 |

| 5 | 1.845 | 4.193 | 50.241 | 1.845 | 4.193 | 50.241 | 2.679 | 6.088 | 35.314 |

| 6 | 1.801 | 4.093 | 54.334 | 1.801 | 4.093 | 54.334 | 2.419 | 5.497 | 40.811 |

| 7 | 1.522 | 3.460 | 57.793 | 1.522 | 3.460 | 57.793 | 2.409 | 5.475 | 46.286 |

| 8 | 1.451 | 3.297 | 61.090 | 1.451 | 3.297 | 61.090 | 2.402 | 5.460 | 51.746 |

| 9 | 1.298 | 2.951 | 64.041 | 1.298 | 2.951 | 64.041 | 2.385 | 5.420 | 57.166 |

| 10 | 1.261 | 2.866 | 66.907 | 1.261 | 2.866 | 66.907 | 2.352 | 5.346 | 62.512 |

| 11 | 1.238 | 2.813 | 69.720 | 1.238 | 2.813 | 69.720 | 2.343 | 5.324 | 67.836 |

| 12 | 1.075 | 2.444 | 72.164 | 1.075 | 2.444 | 72.164 | 1.904 | 4.327 | 72.163 |

| Path | Estimate | AVE | CR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMI3 | ← | Visual | OMI (sensory attributes) | 0.772 | 0.637 | 0.840 |

| OMI2 | ← | 0.743 | ||||

| OMI1 | ← | 0.874 | ||||

| OMI9 | ← | Tactile | 0.775 | 0.613 | 0.826 | |

| OMI8 | ← | 0.744 | ||||

| OMI7 | ← | 0.828 | ||||

| OMI6 | ← | Auditory | 0.754 | 0.611 | 0.824 | |

| OMI5 | ← | 0.762 | ||||

| OMI4 | ← | 0.826 | ||||

| OMI11 | ← | Gustatory | 0.889 | 0.738 | 0.849 | |

| OMI10 | ← | 0.828 | ||||

| OMI14 | ← | Olfactory | 0.823 | 0.649 | 0.847 | |

| OMI13 | ← | 0.792 | ||||

| OMI12 | ← | 0.802 | ||||

| OMI21 | ← | Autonomy | OMI (structural features) | 0.720 | 0.565 | 0.838 |

| OMI20 | ← | 0.706 | ||||

| OMI19 | ← | 0.748 | ||||

| OMI18 | ← | 0.826 | ||||

| OMI17 | ← | Spatial | 0.767 | 0.644 | 0.844 | |

| OMI16 | ← | 0.817 | ||||

| OMI15 | ← | 0.822 | ||||

| OMI23 | ← | Kinesthetic | 0.894 | 0.761 | 0.864 | |

| OMI22 | ← | 0.850 | ||||

| G1 | ← | Accessibility | Mall Management Dimensions | 0.850 | 0.561 | 0.884 |

| G2 | ← | 0.714 | ||||

| G3 | ← | 0.741 | ||||

| G4 | ← | 0.743 | ||||

| G5 | ← | 0.716 | ||||

| G6 | ← | 0.720 | ||||

| G7 | ← | Tenant Mix | 0.830 | 0.568 | 0.840 | |

| G8 | ← | 0.719 | ||||

| G9 | ← | 0.710 | ||||

| G10 | ← | 0.750 | ||||

| G11 | ← | Entertainment | 0.863 | 0.599 | 0.856 | |

| G12 | ← | 0.732 | ||||

| G13 | ← | 0.730 | ||||

| G14 | ← | 0.764 | ||||

| S1 | ← | Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.859 | 0.692 | 0.900 | |

| S2 | ← | 0.809 | ||||

| S3 | ← | 0.842 | ||||

| S4 | ← | 0.817 | ||||

| L1 | ← | Mall loyalty | 0.830 | 0.614 | 0.826 | |

| L2 | ← | 0.747 | ||||

| L3 | ← | 0.771 | ||||

| Vis- | Aud- | Tac- | Gus- | Olf- | Spa- | Aut- | Kin- | Acc- | Ten- | Ent- | Sho- | Mal- | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMI (sensory attributes) | Visual | 0.798 | ||||||||||||

| Auditory | 0.268 | 0.783 | ||||||||||||

| Tactile | 0.329 | 0.292 | 0.781 | |||||||||||

| Gustatory | 0.347 | 0.267 | 0.391 | 0.859 | ||||||||||

| Olfactory | 0.315 | 0.251 | 0.356 | 0.381 | 0.806 | |||||||||

| OMI (structural features) | Spatial | 0.383 | 0.326 | 0.382 | 0.389 | 0.439 | 0.751 | |||||||

| Autonomy | 0.325 | 0.280 | 0.348 | 0.333 | 0.314 | 0.417 | 0.802 | |||||||

| Kinesthetic | 0.289 | 0.353 | 0.303 | 0.216 | 0.250 | 0.316 | 0.229 | 0.872 | ||||||

| Mall Management Dimensions | Accessibility | 0.353 | 0.235 | 0.252 | 0.263 | 0.240 | 0.317 | 0.335 | 0.207 | 0.749 | ||||

| Tenant Mix | 0.345 | 0.298 | 0.285 | 0.424 | 0.324 | 0.404 | 0.385 | 0.336 | 0.338 | 0.754 | ||||

| Entertainment | 0.294 | 0.346 | 0.409 | 0.322 | 0.378 | 0.398 | 0.383 | 0.305 | 0.394 | 0.367 | 0.774 | |||

| Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.490 | 0.423 | 0.519 | 0.539 | 0.510 | 0.572 | 0.489 | 0.418 | 0.442 | 0.537 | 0.555 | 0.832 | ||

| Mall loyalty | 0.376 | 0.317 | 0.287 | 0.239 | 0.256 | 0.371 | 0.390 | 0.295 | 0.299 | 0.330 | 0.315 | 0.462 | 0.783 | |

| Index | Expected Value | Actual Value | Fitting Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit index | |||

| CMIN/DF | <3 | 1.357 | Acceptable |

| GFI | >0.8 | 0.881 | Acceptable |

| AGFI | >0.8 | 0.857 | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.032 | Acceptable |

| Comparative fitting indicators | |||

| NFI | >0.8 | 0.879 | Acceptable |

| IFI | >0.8 | 0.965 | Acceptable |

| TLI | >0.8 | 0.959 | Acceptable |

| CFI | >0.8 | 0.965 | Acceptable |

| Parsimonious fitting index | |||

| PNFI | >0.5 | 0.766 | Acceptable |

| PCFI | >0.5 | 0.84 | Acceptable |

| Vis- | Aud- | Tac- | Gus- | Olf- | Spa- | Aut- | Kin- | Acc- | Ten- | Ent- | Sho- | Mal- | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMI (sensory attributes) | Visual | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Auditory | 0.268 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Tactile | 0.329 ** | 0.292 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Gustatory | 0.347 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.391 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Olfactory | 0.315 ** | 0.251 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.381 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| OMI (structural features) | Spatial | 0.383 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.439 ** | 1 | |||||||

| Autonomy | 0.325 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.417 ** | 1 | |||||||

| Kinesthetic | 0.289 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.303 ** | 0.216 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.229 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Mall Management Dimensions | Accessibility | 0.353 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.263 ** | 0.240 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.335 ** | 0.207 ** | 1 | ||||

| Tenant Mix | 0.345 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.338 ** | 1 | ||||

| Entertainment | 0.294 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.378 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.367 ** | 1 | |||

| Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.490 ** | 0.423 ** | 0.519 ** | 0.539 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.572 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.555 ** | 1 | ||

| Mall loyalty | 0.376 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.239 ** | 0.256 ** | 0.371 ** | 0.390 ** | 0.295 ** | 0.299 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.315 ** | 0.462 ** | 1 | |

| Index | Expected Value | Actual Value | Fitting Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit index | |||

| CMIN/DF | <3 | 2.315 | Acceptable |

| GFI | >0.8 | 0.696 | Reject |

| AGFI | >0.8 | 0.662 | Reject |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.061 | Acceptable |

| Comparative fitting indicators | |||

| NFI | >0.8 | 0.777 | Reject |

| IFI | >0.8 | 0.86 | Acceptable |

| TLI | >0.8 | 0.85 | Acceptable |

| CFI | >0.8 | 0.859 | Acceptable |

| Parsimonious fitting index | |||

| PNFI | >0.5 | 0.731 | Acceptable |

| PCFI | >0.5 | 0.808 | Acceptable |

| Index | Expected Value | Actual Value | Fitting Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit index | |||

| CMIN/DF | <3 | 1.373 | Acceptable |

| GFI | >0.8 | 0.878 | Acceptable |

| AGFI | >0.8 | 0.855 | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.032 | Acceptable |

| Comparative fitting indicators | |||

| NFI | >0.8 | 0.876 | Acceptable |

| IFI | >0.8 | 0.963 | Acceptable |

| TLI | >0.8 | 0.957 | Acceptable |

| CFI | >0.8 | 0.962 | Acceptable |

| Parsimonious fitting index | |||

| PNFI | >0.5 | 0.773 | Acceptable |

| PCFI | >0.5 | 0.849 | Acceptable |

| Path | Standard Estimate | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMI(sensory attributes) →Shoppers’ Experiences | Visual→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.124 | 0.143 | 0.052 | 2.729 | 0.006 |

| Tactile→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.130 | 0.161 | 0.061 | 2.629 | 0.009 | |

| Auditory→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.073 | 0.089 | 0.055 | 1.621 | 0.105 | |

| Gustatory→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.160 | 0.174 | 0.054 | 3.217 | 0.001 | |

| Olfactory→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.123 | 0.138 | 0.054 | 2.548 | 0.011 | |

| OMI(structural features) →Shoppers’ Experiences | Autonomy→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.082 | 0.115 | 0.066 | 1.744 | 0.081 |

| Spatial→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.154 | 0.178 | 0.062 | 2.870 | 0.004 | |

| Kinesthetic→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.084 | 0.086 | 0.045 | 1.910 | 0.056 | |

| Mall Management Dimensions →Shoppers’ Experiences | Accessibility→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.078 | 0.070 | 0.039 | 1.819 | 0.069 |

| Tenant Mix→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.135 | 0.129 | 0.048 | 2.697 | 0.007 | |

| Entertainment→Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.147 | 0.132 | 0.044 | 3.013 | 0.003 | |

| Shoppers’ Experiences→Mall loyalty | 0.549 | 0.597 | 0.064 | 9.363 | *** | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.455 ** (66.146) | 4.455 ** (66.260) | 4.423 ** (69.550) |

| Shoppers’ Experiences | 0.662 ** (9.820) | 0.655 ** (9.696) | 0.675 ** (10.586) |

| Motivational orientation | 0.101 (1.492) | 0.112 (1.751) | |

| Shoppers’ Experiences × Motivational orientation | 0.425 ** (6.711) | ||

| n | 358 | 358 | 358 |

| R2 | 0.213 | 0.218 | 0.306 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.211 | 0.214 | 0.300 |

| F | F = 96.432, p = 0.000 | F = 49.494, p = 0.000 | F = 52.103, p = 0.000 |

| △R2 | 0.213 | 0.005 | 0.088 |

| △F | F = 96.432, p = 0.000 | F = 2.225, p = 0.137 | F = 45.040, p = 0.000 |

| Hypothesis Statement | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| OMI (sensory attributes) →Shoppers’ Experience | H1: Visual in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Accepted |

| H2: Tactile in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Accepted | |

| H3: Auditory in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Rejected | |

| H4: Gustatory in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Accepted | |

| H5: Olfactory in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Accepted | |

| OMI (structural features) →Shoppers’ Experience | H6: Autonomy in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Rejected |

| H7: Spatial in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Accepted | |

| H8: Kinesthetic in mental imagery positively influences shoppers’ experiences. | Rejected | |

| Mall Management Dimensions →Shoppers’ Experience | H9: Accessibility exerts a positive impact on shoppers’ experiences. | Rejected |

| H10: Tenant mix is positively related to shoppers’ experiences. | Accepted | |

| H11: Entertainment has a positive impact on shoppers’ experiences.. | Accepted | |

| Shoppers’Experience →Mall loyalty | H12: Shoppers’ experiences have a positive impact on mall loyalty. | Accepted |

| Moderating Role 0f Motivation Orientation | H13: Shoppers’ experiences have a stronger effect on loyalty for hedonic than utilitarian motivational orientation. | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Z.; Chung, W. Enhancing Shoppers’ Experiences and Building Mall Loyalty: The Role of Octomodal Mental Imagery (OMI) and Management Dimension-Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region of China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411412

Zhu Z, Chung W. Enhancing Shoppers’ Experiences and Building Mall Loyalty: The Role of Octomodal Mental Imagery (OMI) and Management Dimension-Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region of China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):11412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411412

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Zhenxing, and Wonjun Chung. 2023. "Enhancing Shoppers’ Experiences and Building Mall Loyalty: The Role of Octomodal Mental Imagery (OMI) and Management Dimension-Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta Region of China" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 11412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411412