Exploring the Image, Perceived Authenticity, and Perceived Value of Underground Built Heritage (UBH) and Its Role in Motivation to Visit: A Case Study of Five Different Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Perceived Authenticity

2.2. Perceived Value

2.3. Heritage Image

2.4. Heritage Tourist Motivation

2.5. Loyalty

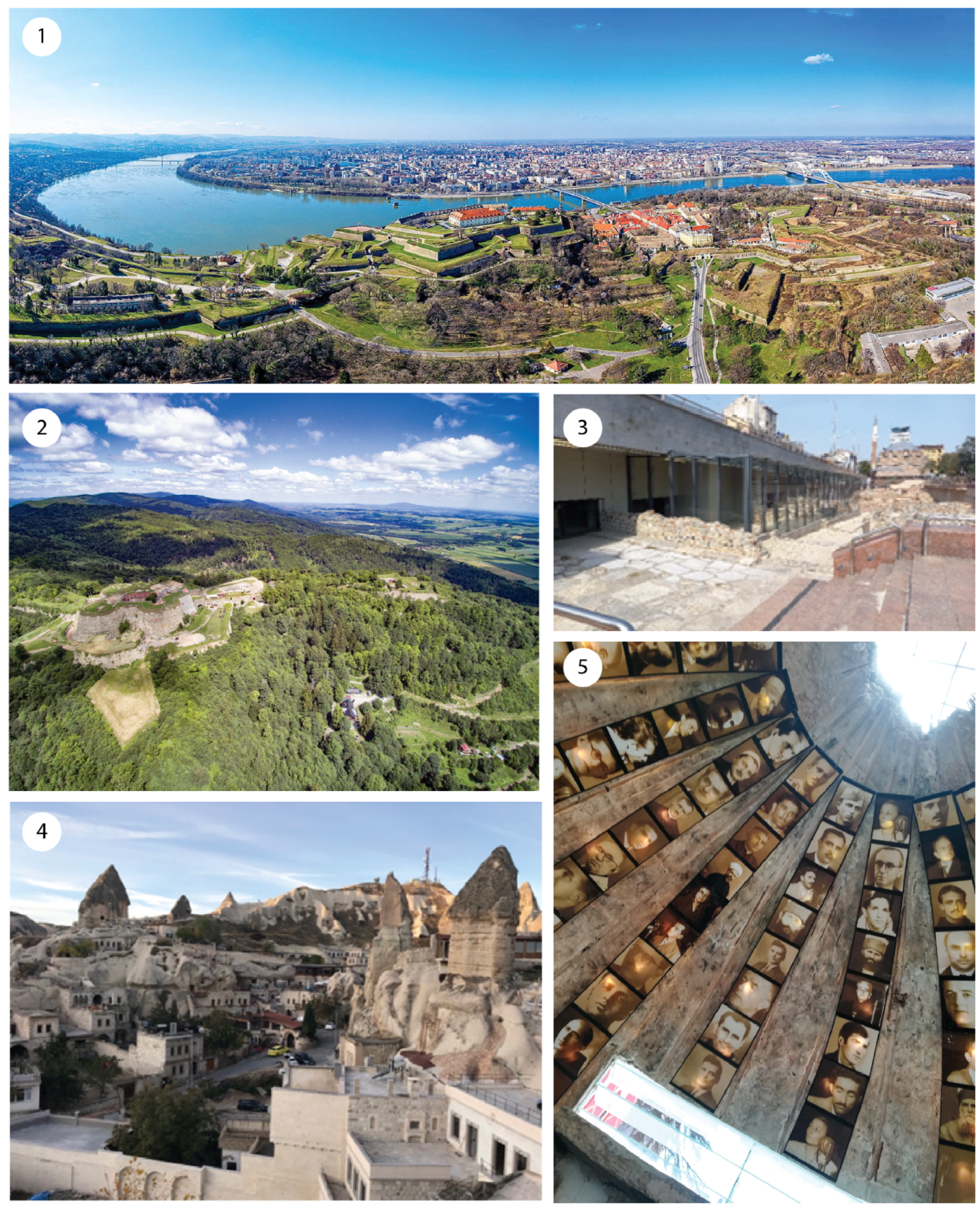

3. Study Area

4. Methodology

4.1. Instrument

4.2. Participants

4.3. Procedure

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Model Validity

5.2. The Results of the ANOVA Test

5.3. The Results of the Path Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Menezes, M.; Ivanova-Radovanova, P.; Ruchinskaya, T.; Lalenis, K.; Bocci, M. Planning Perspectives and Approaches for Activating Underground Built Heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, R.; Genovese, L. Underground Built Heritage (UBH) as Valuable Resource in China, Japan and Italy. Heritage 2021, 4, 3208–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, R.; Ciaravino, R. Underground Built Heritage and Food Production: From the Theoretical Approach to a Case/Study of Traditional Italian “Cave Cheeses”. Heritage 2022, 5, 1865–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgoglione, L.; Malinverni, E.S.; Smaniotto Costa, C.; Pierdicca, R.; Di Stefano, F. Exploiting 2D/3D Geomatics Data for the Management, Promotion, and Valorization of Underground Built Heritage. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, R. Underground Built Heritage: A Theoretical Approach for the Definition of an International Class. Heritage 2021, 4, 1092–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, V.M.; González-Rodríguez, R.; Díaz Fernández, M.C. The relevance of motivation, authenticity and destination image to explain future behavioural intention in a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 650–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpi, D.; Raggiotto, F. A construal level view of contemporary heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Jimenez, C. (Ed.) The Conservation of Subterranean Cultural Heritage, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, J.M.F.; Guerrero, I.C. Subterranean wine cellars of Central-Spain (Ribera de Duero): An underground built heritage to preserve. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2006, 21, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presti, O.L.; Carli, M.R. Italian catacombs and their digital presence for underground heritage sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, F.; Torresani, A.; Farella, E.M.; Pierdicca, R.; Menna, F.; Remondino, F. 3D surveying of underground built heritage: Opportunities and challenges of mobile technologies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimic, K.; Costa, C.S.; Negulescu, M. Creating tourism destinations of underground built heritage–the cases of salt mines in Poland, Portugal, and Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousazadeh, H.; Ghorbani, A.; Azadi, H.; Almani, F.A.; Zangiabadi, A.; Zhu, K.; Dávid, L.D. Developing Sustainable Behaviors for Underground Heritage Tourism Management: The Case of Persian Qanats, a UNESCO World Heritage Property. Land 2023, 12, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 904–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. Links between tourists, heritage, and reasons for visiting heritage sites. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Cheung, C. Chinese heritage tourists to heritage sites: What are the effects of heritage motivation and perceived authenticity on satisfaction? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Leou, C.H. A study of tourism motivation, perceived value and destination loyalty for Macao cultural and heritage tourists. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2015, 7, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly-Boyd, J.M. Existential Authenticity: Place Matters. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunel, M.C.; Erkurt, B. Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Positioning Museums on an Authenticity Continuum. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Travel and Tourism; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, C. Contested National Tragedies: An Ethical Dimension. In The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism; Richard, S., Stone, P.R., Eds.; Channel View Publications Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Asplet, M.; Cooper, M. Cultural designs in New Zealand souvenir clothing: The question of authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory for the Leisure Class; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Waitt, G. Consuming Heritage. Perceived Historical Authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. Cultural Tourism in Botswana and the Sexaxa Cultural Village: A Case Study. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection 725. 2009. Available online: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1729&context=isp_collection (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Silberberg, T. Cultural Tourism and Business Opportunities for Museums and Heritage Sites. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M. Os museus e a autenticidade no turismo. Rev. Itiner. 2008, 1, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, G.L.M.; Guzmán, T.L.; Molina, D.L.; Gálvez, J.C. Heritage tourism in the Andes: The case of Cuenca, Ecuador. Anatolia 2018, 29, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, J. Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Edelheim, J.R. Rethinking traditional Chinese culture: A consumer-based model regarding the authenticity of Chinese calligraphic landscape. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage tourism in the 21st century: Valued traditions and new perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, A. The convergence process in heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, F.; Eren, D. Serial mediation: Destination image and perceived value in the relationship between perceived authenticity and behavioural intentions. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 33, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.; Curran, R.; O’Gorman, K.; Taheri, B. Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, X.; Lin, V.S.; Jin, W.; Luo, Q. The authenticity of heritage sites, tourists’ quest for existential authenticity, and destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, C. Services Marketing, People, Technology, Strategy, 4th ed.; Pearson/Prentice-Hall: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ulaga, W.; Chacour, S. Measuring customer-perceived value in business markets: A prerequisite for marketing strategy development and implementation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajh, S.P. Comparison of perceived value structural models. Tržište/Market 2012, 24, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, F. Tourists’ perceived value model and its measurement: An empirical study. Tour. Tribune 2007, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, L.; Cai, L.; Yang, Z. Tourist perceived value of Wetland Park: Evidence from Xixi and Qinhu lake. Tour. Tribune 2014, 29, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, D.; Ma, E. Perceived value of, and experience with, a World Heritage Site in China—The case of Kaiping Diaolou and villages in China. J. Her. Tour. 2022, 17, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.X.; Chi, C.; Xu, H.G. Development destination loyalty: The case of Hainan island. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D. Image as a factor in tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1975, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindell, A. Time in corporate images: Introducing image heritage and image-in-use. Qual. Mark. Res. 2013, 16, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer based equity. J. Mark. 1993, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, H.; Hanzaee, K.H. The effects of heritage image on destination branding: An Iranian perspective. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindell, A. Image Heritage—The Temporal Dimension in Consumers’ Corporate Image Constructions; Svenska Handelshögskolan: Helsinki, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Suhud, U.; Allan, M.; Willson, G. The Relationship between Push-Pull Motivation, Destination Image, and Stage of Visit Intention: The Case of Belitung Island. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2021, 14, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, S.M.; Liang, G.S.; Yang, S.H. The relationships of cruise image, perceived value, satisfaction, and post-purchase behavioral intention on Taiwanese tourists. Afr. J. Bus. Mang. 2011, 5, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Taşçı, A.; Gartner, W. Destination Image and Its Functional Relationships. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Biran, A. Heritage site management—Motivations and Expectations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lin, X.; Choe, Y.; Li, W. In the Eyes of the Beholder: The Effect of the Perceived Authenticity of Sanfang Qixiang in Fuzhou, China, among Locals and Domestic Tourists. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Contemporary cultural heritage and tourism: Development issues and emerging trends. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D.; Healy, R.; Sills, E. Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, V.T.C.; Clarke, J.R. Marketing in Travel and Tourism; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Laguna-Garcia, M. Towards a new approach of destination royalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, J.A.J.; Hernández-Rojas, R.D.; Vergara-Romero, A.; Dancausa, M.G. Loyalty in Heritage Tourism: The Case of Córdoba and Its Four World Heritage Sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, M.; Mišić, S. Are Vauban’s Geometrical Principles Applied in the Petrovaradin Fortress? Nexus Netw. J. 2014, 16, 751–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lukić, T.; Pivac, T.; Cimbaljević, M.; Ðerčan, B.; Bubalo Živković, M.; Besermenji, S.; Penjišević, I.; Golić, R. Sustainability of Underground Heritage; The Example of the Military Galleries of the Petrovaradin Fortress in Novi Sad, Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojlović, A.; Ivkov-Džigurski, A.; Andrian, G.; Aleksić, N. The Comparative Analysis of Tourism Potentials of Belgrade and Petrovaradin Fortress in Serbia. Geografie 2010, 20, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Milković, V. Petrovaradinska Tvrđava: Podzemlje i Nadzemlje: Mappe; Vrelo: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Besermenji, S.; Pivac, T.; Wallrabenstein, K. Significance of the authentic ambience of the Petrovaradin Fortress on the attractiveness of Exit Festival. Geogr. Pannon. 2009, 13, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisić, V.; Tomka, G. Introduction: Petrovaradin fortress meets HUL. In Petrovaradin; Europa Nostra: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2019; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Službeni list AP Vojvodine br. 25/91 (Official Gazette of AP Vojvodina, No. 25/91). Available online: http://www.zzskgns.rs/prostorno-kulturno-istorijske-celine/ (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Podruczny, G.; Przerwa, T. (Eds.) Twierdza Srebrna Góra, 1st ed.; Bellona: Warszawa, Poland, 2010; ISBN 9788311119239. [Google Scholar]

- Potyrała, J. Twierdza Srebrna Góra, jej losy zapisane w krajobrazie [Srebrna Góra Fortress, its Lot Written in the Landscape]. Archit. Kraj. 2017, 2, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Klancewicz, R.; BasińskiSrebrna, G. Srebrna Góra—18th-Century Mountain Fortress, 2023, National Institute of Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://zabytek.pl/en/obiekty/srebrna-gora-twierdza-srebrnogorska-nowozytna-warownia-gorska-z- (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Klupsz, L. Rozwój idei ochrony obszarowej zabytków. In Forteczne Parki Kulturowe Szansą na Ochronę Zabytków Architektury Obronnej. Fortyfikacja Europejskim Dziedzictwem Kultury, XVI, 1st ed.; Zarząd Główny Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Fortyfikacji: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Molski, P. Idea fortecznych parków kulturowych. In Forteczne Parki Kulturowe Szansą na Ochronę Zabytków Architektury Obronnej. Fortyfikacja Europejskim Dziedzictwem Kultury, XVI, 1st ed.; Zarząd Główny Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Fortyfikacji: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Uchwała nr 42 /VII/2002 Rady Gminy Stoszowice z dnia 20.06.2002 r. w Sprawie Ustanowienia Fortecznego Parku Kulturowego w Srebrnej Górze jako Formy Ochrony Prawnej Krajobrazu Kulturowego oraz Zachowania Wyróżniających się Krajobrazowo Terenów z zabytkami Nieruchomymi; Gmina Stoszowice: Gmina Stoszowice, Poland, 2002.

- Serdica Ancient Cultural and Communicative Complex. Available online: https://www.sofiahistorymuseum.bg/en/chain-offices/serdica-ancient-cultural-and-communicative-complex (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Sofia and Belgrade: Archaeological Pearls; National Archaeological Institute with Museum—Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria; Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019; ISBN 978-954-9472-76-9.

- The Archeological Heritage at Saint Nedelya Square; National Archaeological Institute with Museum—Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2020; ISBN 978-954-9472-97-4.

- Available online: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-necropolis-of-st-sophia-church (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Gülyaz, M.; Ölmez, İ. Cappadocia, 4th ed.; DünyaKitap: Nevşehir, Turkey, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Akkar Ercan, M. Case Study: Göreme in Cappadocia, Turkey. In Underground Built Heritage Valorisation: A Handbook; Pace, G., Salvarini, R., Eds.; CNR Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2021; pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nevşehir Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. Official Website of Nevşehir Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. 2023. Available online: https://nevsehir.ktb.gov.tr/TR-230429/muzeoren-yeri-ziyaretci-sayilari.html (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- BUNK’ART. Available online: https://bunkart.al/1/home (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Isto, R. “An Itinerary of the Creative Imagination”: Bunk’Art and the Politics of Art and Tourism in Remembering Albania’s Socialist Past, Cultures of History Forum. 2017. Available online: https://www.cultures-of-history.uni-jena.de/politics/albania/an-itinerary...-the-politics-of-art-and-tourism-in-remembering-albanias-socialist-past/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- OSCE. Citizens Understanding and Perceptions of the Communist Past in Albania and Expectations for the Future; Organization for Security and Organization in Europe (OSCE): Tirana, Albania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Velikonja, M. Lost in transition: Nostalgia for socialism in post-socialist countries. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2009, 23, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSTAT Tourism in Figures, Albania 2020; Institute of Statistics in Albania: Tirana, Albania. Available online: https://www.instat.gov.al/media/9547/tourism-in-figures-albania-2020-en-__.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- INSTAT. Statistika te Kultures, 2021; INSTAT: Tirana, Albania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Wang, Y.M.; Wu, T.W.; Wang, P.A. An empirical analysis of the antecedents and performance consequences of using the Moodle platform. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2013, 3, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaiţ, A.; Bertea, P.E. Methods for testing discriminant validity. Manag. Mark. J. 2011, 9, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

| Country of Residence (%) | Education (%) |

| Serbia 20.44 | Elementary school 0.9 |

| Poland 19.84 | Secondary school 25.4 |

| Bulgaria 19.84 | Higher school 13.9 |

| Turkey 20.04 | Bachelor 53.8 |

| Albania 19.84 | Master, PhD 6 |

| Gender (%) | Monthly income (%) |

| Male 35.5 | Below average 33.4 |

| Average 45.2 | |

| Female 64.5 | Above average 21.4 |

| Age | How often do you visit heritage sites when you travel? (%) |

| 1. Very rarely 0 | |

| 2. Rarely 0 | |

| Mean 35.04, Std. 14.39 | 3. From time to time 48.2 |

| 4. Often 41.3 | |

| 5. Very often/regularly 10.5 |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation | Cronbach α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Authenticity | 4.3088 | 0.86141 | 0.884 | 0.47 | 0.086 |

| Constructive Authenticity | 3.5772 | 0.88164 | 0.787 | 0.45 | 0.080 |

| Comparison Authenticity | 3.9572 | 0.97404 | 0.847 | 0.44 | 0.061 |

| Existential Authenticity | 4.2525 | 1.10298 | 0.731 | 0.43 | 0.087 |

| Functional value | 4.0021 | 0.88943 | 0.932 | 0.51 | 0.89 |

| Monetary value | 3.5446 | 0.78016 | 0.787 | 0.45 | 0.82 |

| Emotional value | 4.1717 | 0.84970 | 0.918 | 0.56 | 0.88 |

| Social value | 2.9774 | 1.07025 | 0.822 | 0.55 | 0.79 |

| Brand value | 3.7404 | 0.88759 | 0.819 | 0.47 | 0.78 |

| Loyalty | 4.0357 | 0.97092 | 0.882 | 0.75 | 0.92 |

| Heritage image | 4.2566 | 0.86985 | 0.823 | 0.74 | 0.89 |

| Motivation to visit a heritage site | 3.5806 | 0.78934 | 0.895 | 0.46 | 0.93 |

| L | I | M | OA | CA | COMA | EA | FV | MV | EV | SV | BV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loyalty (L) | 0.75 | |||||||||||

| Heritage image (I) | 0.37 | 0.7 | ||||||||||

| Motivation (M) | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.46 | |||||||||

| Objective Authenticity (OA) | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.47 | ||||||||

| Constructive Authenticity (CA) | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.45 | |||||||

| Comparison Authenticity (COMA) | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.150 | 0.044 | ||||||

| Existential Authenticity (EA) | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.043 | |||||

| Functional value (FV) | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.51 | ||||

| Monetary value (MV) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.045 | |||

| Emotional value (EV) | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.56 | ||

| Social value (SV) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.55 | |

| Brand value (BV) | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.047 |

| Variables | F | Sig. | Post Hoc * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loyalty | 31.311 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 | |||

| Heritage image | 33.296 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 5 |

| 4 > 1, 2, 3, 5 | |||

| 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 | |||

| Motivation | 41.662 | 0.000 | 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| 2 > 1, 3 | |||

| 2 < 4, 5 | |||

| 4 > 1, 2, 3, 5 | |||

| 5 > 1, 2, 3 | |||

| Objective Authenticity | 49.26 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 | |||

| Constructive Authenticity | 3.372 | 0.01 | 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Comparison Authenticity | 20.535 | 0.000 | 5 > 2, 3, 4 |

| 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 | |||

| Existential Authenticity | 22.586 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 | |||

| Functional value | 42.497 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 | |||

| Monetary value | 81.229 | 0.000 | 4 > 2, 3, 5 |

| 2 < 1, 3, 4, 5 | |||

| Emotional value | 26.513 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 < 1, 2, 4, 5 | |||

| Social value | 6.603 | 0.000 | 4 > 2, 3, 5 |

| 2 < 1, 3, 4, 5 | |||

| Brand value | 9.769 | 0.000 | 1 > 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| 4 > 2, 3, 5 |

| Model | S–Bχ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | CFI | NFI | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 611.647 | 22 | 27.80 | 0.231 (0.215–0.247) | 0.256 | 0.807 | 0.804 | 0.810 |

| 2 | 473.201 | 30 | 15.773 | 0.171 (0.158–0.185) | 0.233 | 0.855 | 0.849 | 0.857 |

| 3 | 70.114 | 25 | 2.85 | 0.060 (0.044–0.077) | 0.034 | 0.985 | 0.941 | 0.985 |

| 4 | 79.309 | 29 | 2.73 | 0.59 (0.043–0.074) | 0.036 | 0.984 | 0.963 | 0.984 |

| Confirmed Direct Significant Relationships | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructive Authenticity | → | Social value | 0.458 | 0.046 | 9.917 | *** |

| Objective Authenticity | → | Brand value | 0.226 | 0.05 | 4.561 | *** |

| Objective Authenticity | → | Functional value | 0.678 | 0.033 | 20.486 | *** |

| Constructive Authenticity | → | Brand value | 0.137 | 0.042 | 3.262 | 0.001 |

| Comparison Authenticity | → | Brand value | 0.175 | 0.041 | 4.251 | *** |

| Objective Authenticity | → | Monetary value | 0.381 | 0.037 | 10.377 | *** |

| Objective Authenticity | → | Emotional value | 0.523 | 0.038 | 13.816 | *** |

| Existential Authenticity | → | Emotional value | 0.113 | 0.026 | 4.365 | *** |

| Objective Authenticity | → | Heritage image | 0.392 | 0.049 | 8.077 | *** |

| Constructive Authenticity | → | Heritage image | 0.093 | 0.04 | 2.332 | 0.02 |

| Functional value | → | Heritage image | 0.224 | 0.046 | 4.899 | *** |

| Brand value | → | Heritage image | 0.176 | 0.039 | 4.517 | *** |

| Social value | → | Heritage image | −0.088 | 0.031 | −2.832 | 0.005 |

| Heritage image | → | Loyalty | 0.395 | 0.035 | 11.212 | *** |

| Constructive Authenticity | → | Motivation | 0.272 | 0.034 | 8.003 | *** |

| Monetary value | → | Motivation | 0.168 | 0.035 | 4.795 | *** |

| Social value | → | Motivation | 0.156 | 0.027 | 5.707 | *** |

| Monetary value | → | Loyalty | −0.098 | 0.035 | −2.754 | 0.006 |

| Emotional value | → | Loyalty | 0.177 | 0.038 | 4.614 | *** |

| Comparison Authenticity | → | Loyalty | 0.138 | 0.03 | 4.617 | *** |

| Heritage image | → | Motivation | 0.268 | 0.033 | 8.08 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovačić, S.; Pivac, T.; Akkar Ercan, M.; Kimic, K.; Ivanova-Radovanova, P.; Gorica, K.; Tolica, E.K. Exploring the Image, Perceived Authenticity, and Perceived Value of Underground Built Heritage (UBH) and Its Role in Motivation to Visit: A Case Study of Five Different Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511696

Kovačić S, Pivac T, Akkar Ercan M, Kimic K, Ivanova-Radovanova P, Gorica K, Tolica EK. Exploring the Image, Perceived Authenticity, and Perceived Value of Underground Built Heritage (UBH) and Its Role in Motivation to Visit: A Case Study of Five Different Countries. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511696

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovačić, Sanja, Tatjana Pivac, Müge Akkar Ercan, Kinga Kimic, Petja Ivanova-Radovanova, Klodiana Gorica, and Ermelinda Kordha Tolica. 2023. "Exploring the Image, Perceived Authenticity, and Perceived Value of Underground Built Heritage (UBH) and Its Role in Motivation to Visit: A Case Study of Five Different Countries" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511696

APA StyleKovačić, S., Pivac, T., Akkar Ercan, M., Kimic, K., Ivanova-Radovanova, P., Gorica, K., & Tolica, E. K. (2023). Exploring the Image, Perceived Authenticity, and Perceived Value of Underground Built Heritage (UBH) and Its Role in Motivation to Visit: A Case Study of Five Different Countries. Sustainability, 15(15), 11696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511696