‘Should I Go or Should I Stay?’ Why Do Romanians Choose the Bulgarian Seaside for Their Summer Holiday?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

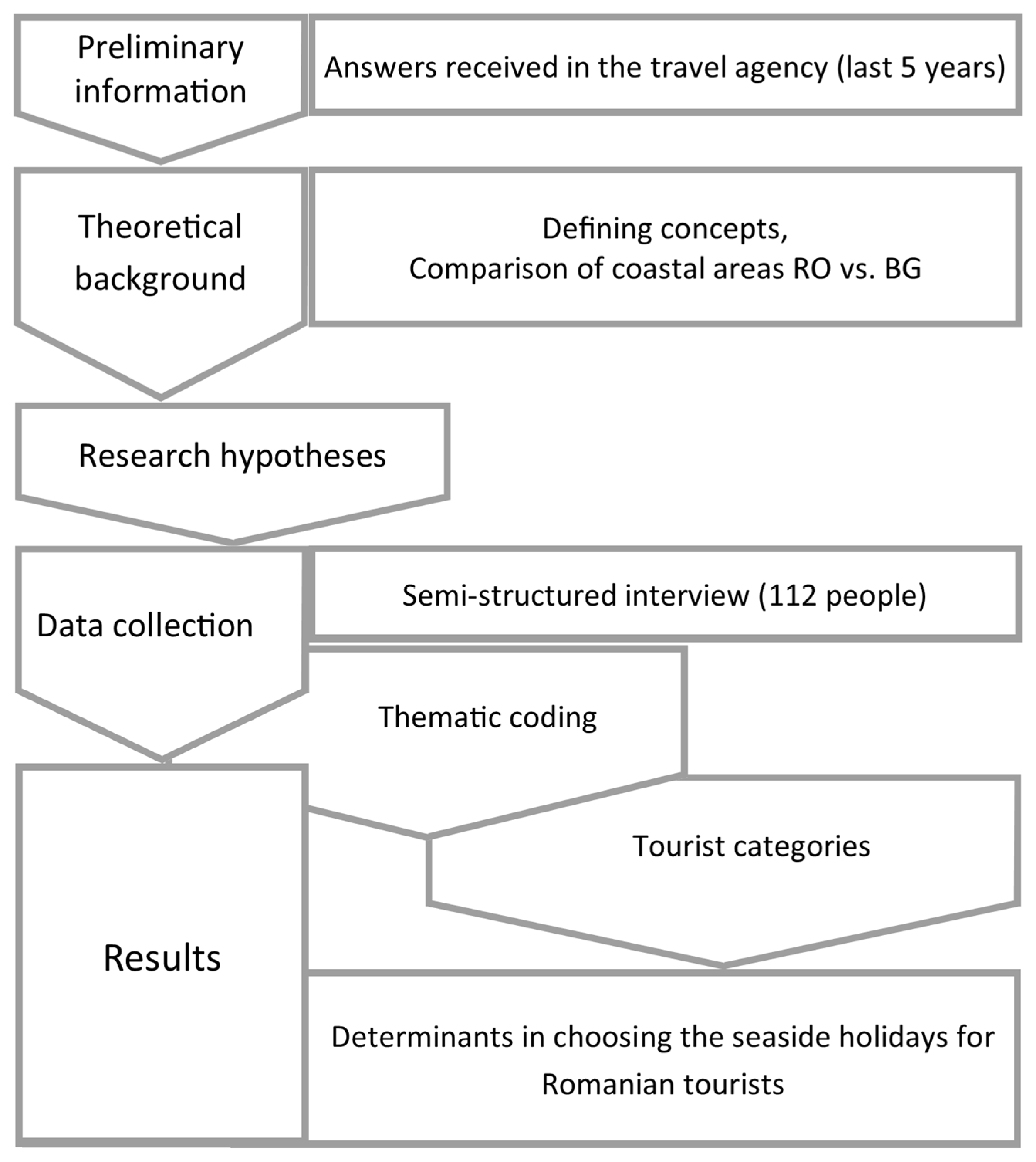

3. Materials and Methods

4. Romanian Versus Bulgarian Seacoast—An Overview

5. Results

5.1. Main Motives

5.2. Types of Tourists

- Tourists who choose the Bulgarian seaside due to the superior standard of services. This category had the largest representation at 38% of those interviewed; it was especially made up by families with children, 25–55 years old, and generally college graduates with white-collar jobs.

- Tourists who chose the Bulgarian seaside as it was the cheapest option for accommodation and meals. These tourists represented 31% of those interviewed, and they belong to all age categories, confirming the low willingness to spend of the Romanians visiting Bulgaria [64].

- 3.

- Tourists who chose the Romanian seaside, even if they would prefer the Bulgarian cost. These were mainly employees of public institutions who went on vacation in Bulgaria in the past and now receive holiday vouchers that can only be used in an authorized accommodation structure in Romania. This category represented 16% of the interviewed tourists, people aged between 25 and 64 years old, either single or families with one or more children; they would have preferred a holiday in Bulgaria, but since they can afford only one summer vacation, they chose the Romanian seaside, with part of the holiday being subsidized by the holiday vouchers. This category confirmed hypothesis H1b, that more Romanians would choose the Bulgarian seaside for their holiday if they could. However, due to the stipulations of the Romanian legislation for the use of holiday vouchers and their limited income, they spent their only holiday on the Romanian seaside. They generally chose budget or mid-range hotels, with breakfast only, and the rest of the meal expenses were paid on the spot.

- 4.

- Tourists who choose the Romanian seaside considering that there were impediments to choosing Bulgaria or that the Bulgarian seaside was not even attractive, at 9% of the total. In this category, we included tourists who considered Bulgaria risky because of the car thefts and robberies presented in the media [78,79,80], tourists who did not travel abroad due to not knowing a foreign language or who foresaw a difficulty in using a foreign currency or means of transport to another country, and those who categorized the Bulgarian seaside as intended only for mass tourism, not seeing its attractiveness. This category was in line with hypothesis H1c, but it should be noted that only a small number of Romanian tourists (accounting for just 9% of the interviewed persons) supported this finding.

- 5.

- Young people who definitely preferred the Romanian seaside. This category accounted for only 6% from the total number of tourists interviewed, and they overlapped the 18–24 age group, who were single and generally students. They chose the Romanian seaside for the entertainment possibilities in the youth resorts (Vama Veche and Costinesti, which are well known in Romania for targeting particularly this demographic) and for the chance to interact more easily with other young people. They did not know the equivalent resorts, dedicated to young people, in Bulgaria. The fact that they also benefited from subsidized rail transportation (those who were in high school could travel for free, no matter the distance, while college students had a 50% discount of the total price with another 5 to 10% discount for group travel) also added to the appeal of the Romanian resorts. However, in reality, the share of this group may be higher, since young people rarely rely on travel agencies for booking their holiday.

6. Discussion

- ■

- The experience of some tourist regions, where the natural landscape is not the main attraction (Bulgarian seaside, Antalya), has shown that the all-inclusive system is a solution for a better capitalization on the tourism infrastructure; if the all-inclusive system proves to be profitable only for large hotels [89], the smaller hotels could offer the ’light all-inclusive’ option, in which the variety of food products is somewhat lower and which allows the exclusion of some alcoholic beverages, thus being able to be implemented with lower costs.

- ■

- Early booking sales combined with all-inclusive services offer an advantage both for the accommodation structures, which receive money in advance, and can plan their supply flow much better knowing quite precisely the occupancy rate but also for tourists, who benefit from a lower price if they pay or book their holiday a few months in advance.

- ■

- The all-inclusive system presents both advantages and disadvantages for stakeholders involved in the tourism industry, but it could offer Romanian tourists a higher standard of meal services, eliminating the consumption at public food establishments with questionable quality, which could also contribute to a positive shift in perception.

- ■

- The partial renovations of the hotel buildings, carried out before the start of each season, would lead to an increased satisfaction of the tourists.

- ■

- In addition to the greater interest that the local authorities must give to the development of public spaces in resorts (parks, promenade areas, and beaches), partnerships between local authorities and accommodation structures could also include the improvement of the public areas transited through by tourists from the hotel to the beach.

- ■

- Facilitation by the public authorities of the creation and development of more events (festivals, sports, gastronomic and cinematographic events, and temporary exhibitions) and the involvement of hotels in sponsoring the events could lead both to higher occupancy rates and to the possibility of higher revenues (prices higher) during these events.

- ■

- Not least, a sincere and fair promotion of the accommodation structures (presentation of the year of total/partial renovation, room size, meals, and entertainment descriptions) will lead to an increase in the degree of trust for the repeat tourists.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ketter, E. Restarting Tourism for the Better. In Performance of European Tourism Before, During and Beyond COVID-19; The European Travel Commission: Atout, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights, 2020 ed.; UNWTO-World Tourism Organization: Madri, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Albă, C.D.; Popescu, L.S. Romanian Holiday Vouchers: A Chance to Travel for Low-Income Employees or an Instrument to Boost the Tourism Industry? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, S.J.; Cox, C. Linking Destination Competitiveness and Destination Development: Findings from a Mature Australian Tourism Destination. In Competition in Tourism: Business and Destination Perspectives, Proceedings of the TTRA 2008 Annual Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 23–25 April 2008; Travel & Tourism Research Association: Lapeer, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, A. A Framework of Tourist Attraction Research. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariya, G.; Wishitemi, B.E.L.; Sitati, N.W. Tourism Destination Attractiveness as Perceived by Tourists Visiting Lake Nakuru National Park, Kenya. Int. J. Res. 2017, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.-C.; Xie, P.F.; Tsai, M.-C. Perceptions of Attractiveness for Salt Heritage Tourism: A Tourist Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, B. Intra-attraction Tourist Spatial-Temporal Behaviour Patterns. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Voiculescu, S.; Jucu, I.S. Introduction: Changing Tourism in the Cities of Post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2020, 22, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, M.; Warcholik, W.; Żemła, M. Destination Familiarity and Perceived Attractiveness of Four Polish Tourism Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. Tourism: Principles and Practice; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cibinskiene, A.; Snieskiene, G. Evaluation of City Tourism Competitiveness. In Proceedings of the 20th International Scientific Conference-Economics and Management 2015 (Icem-2015), Kaunas, Lithuania, 6–8 May 2015; pp. 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Fletcher, J.; Fyall, A.; Gilbert, D.; Wanhill, S.R.C. Tourism Principles and Practice; Prentice Hall Financial Times: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dimoska, T.; Trimcev, B. Competitiveness Strategies for Supporting Economic Development of the Touristic Destination. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, B.; Crouch, G. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI Publishing: Oxon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pansiri, J. Tourist Motives and Destination Competitiveness: A Gap Analysis Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2014, 15, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decrop, A. Destination Choice Sets: An Inductive Longitudinal Approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Hsu, C.H.C. Dyadic Consensus on Family Vacation Destination Selection. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeri, L.; Armenski, T.; Jovanovic, T.; Dragin, A. How Income Influences the Choice of Tourism Destination? Acta Oeconomica 2014, 64, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-H.; Chuang, S.-C.; Huang, M.C.-J.; Weng, S.-T. What Triggers Travel Spending? The Impact of Prior Spending on Additional Unplanned Purchases. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S.; Jovanović, T.; Vujičić, M.D.; Morrison, A.M.; Kennell, J. What Shapes Activity Preferences? The Role of Tourist Personality, Destination Personality and Destination Image: Evidence from Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1803. [Google Scholar]

- Seddighi, H.R.; Theocharous, A.L. A Model of Tourism Destination Choice: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artal-Tur, A.; Correia, A.; Serra, J.; Osorio-Caballero, M. Destination Choice, Repeating Behaviour and the Tourist-Destination Life Cycle Hypothesis: Methods and Protocols. In Trends in Tourist Behavior; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, W.; Wolfe, K.; Hodur, N.; Leistritz, F. Tourist Word of Mouth and Revisit Intentions to Rural Tourism Destinations: A Case of North Dakota, USA. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Hitchcock, M.; Lu, D.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Word of Mouth on Tourism Destination Choice: Tourist–Resident Relationship and Safety Perception among Mainland Chinese Tourists Visiting Macau. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2114. [Google Scholar]

- Confente, I. Twenty-Five Years of Word-of-Mouth Studies: A Critical Review of Tourism Research. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 17, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brey, E.T.; Lehto, X. Changing Family Dynamics: A force of Change for the Family-resort Industry? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbrecht, M.; Shaw, S.M.; Delamere, F.M.; Havitz, M.E. Experiences, perspectives, and meanings of family vacations for children. Leis./Loisir 2008, 32, 541–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Zins, A.H.; Silva, F. Why Do Tourists Persist in Visiting the Same Destination? Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, A.H.; Ketabi, M. The Role of Push and Pull Factors in the Way Tourists Choose Their Destination. Anatolia 2015, 26, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Mansfeld, Y. Toward a Theory of Tourism Security. In Tourism, Security and Safety; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Creţan, R. Andreas Eckert and Felicitas Hentschke: Corona and Work around the Globe. Comp. Southeast Eur. Stud. 2021, 69, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Mousazadeh, H.; Akbarzadeh Almani, F.; Lajevardi, M.; Hamidizadeh, M.R.; Orouei, M.; Zhu, K.; Dávid, L.D. Reconceptualizing Customer Perceived Value in Hotel Management in Turbulent Times: A Case Study of Isfahan Metropolis Five-Star Hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7022. [Google Scholar]

- Mousazadeh, H.; Ghorbani, A.; Azadi, H.; Almani, F.A.; Mosazadeh, H.; Zhu, K.; Dávid, L.D. Sense of Place Attitudes on Quality of Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Iranian Residents in Hungary. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6608. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, L.; Vîlcea, C. General Population Perceptions of Risk in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Romanian Case Study. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2021, 29, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L. Containment and mitigation strategies during the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic. A Territorial Approach in CCE Countries. Forum Geogr. 2021, XIX, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fylan, F. Semi-structured interviewing. In A Handbook of Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology; Miles, J., Gilbert, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A.; Cross, W.E. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond from Research Design to Analysis and Publication; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Drever, E. Using Semi-Structured Interviews in Small-Scale Research: A Teacher’s Guide; Scottish Council for Research in Education: Glasgow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A.-M. Education and Post-communist Transitional Justice: Negotiating the Communist Past in a Memorial Museum. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2019, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, Z.; Káposzta, J.; Ritter, K.; Dávid, L.; Nagy, H.; Farkas, T. The Territorial Significance of Food Hungaricums: The Case of Pálinka. Rom. J. Reg. Sci. 2016, 10, 64–84. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U.; Kardorff, E.V.; Steinke, I. A Companion to Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, T. Using Thematic Analysis in Tourism Research. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbekova, A.; Uysal, M.; Assaf, A.G. A thematic Analysis of Crisis Management in Tourism: A Theoretical Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; Kupka, P.; Powell, R.; Walach, V. Everyday Roma Stigmatization: Racialized Urban Encounters, Collective Histories and Fragmented Habitus. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2022, 46, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Hanson, W.E.; Clark Plano, V.L.; Morales, A. Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 35, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A.-M. Transitional Justice and the Political ‘Work’ of Domestic Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Dumbraveanu, D. Romanian Tourism in the Post-communist Period. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 898–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogramadjieva, E.; Matei, E. Comparative Analysis of Hotel Accommodation Facilities in Bulgaria and Romania in the Period 1990–2007. In Annuaire de L’universite de Sofia “St. Kliment Ohridski”; Faculte de Geologie et Geographie: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 252–280. [Google Scholar]

- Erdeli, G.; Gheorghilas, A. Amenajari Turistice; Editura Universitara: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. Tourism and Development in Communist and Post-Communist Societies; CABI International: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zinganel, M. Enchanting Views–Romanian Black Sea Tourism Planning and Architecture of the 1960s and ’70s. Stud. Hist. Theory Archit. 2014, 2, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachvarov, M. End of the model? Tourism in post-communist Bulgaria. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, A. From Polyglot Playgrounds to Tourist traps? Designing and Redesigning the Modern Seaside Resorts in Bulgaria. Eur. Reg. 2015, 22, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Toneva, P.I. Restrukturiranje Vlasništva Bugarske Hotelske Industrije/Ownership Restructuring of The Hotel Industry in Bulgaria. Acta Tur. 2009, 21, 230–249. [Google Scholar]

- Brânză, G. Evolutions and Trends in The Development of Romanian Seaside Tourism after Romania’s Integration in The European Union. Annals of The University of Petroşani. Economics 2009, IX, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, M.; Hapenciuc, C.-V.; Arionesei, G. Romania Versus Bulgaria: A Short Analysis of the Competitiveness of Seaside Tourism. CBU Int. Conf. Proc. 2016, 4, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, C. The Current Profile of Romanian Hotel Industry: Does It Enhance the Attractiveness of Romania as a Tourist Destination? Stud. UBB Negot. 2014, 59, 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dabeva, T. Elaboration of the Superstructure of the Bulgarian Hotel Industry. UTMS J. Econ. 2010, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tapescu, A.I.M. Romanian versus Bulgarian Tourism Labour Market Analysis. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Economic Conference–IECS 2015 “Economic Prospects in the Context of Growing Global and Regional Interdependencies”, IECS 2015, Sibiu, Romania, 15–16 May 2015; pp. 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Moraru, C. Tourism Contribution to the Economic Growth of Romania; a Regional Comparative Analysis. Rom. Stat. Rev. 2012, 60, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, A.; Bába, É.B.; Kinczel, A.; Molnár, A.; Eszter, J.B.; Papp-Váry, Á.; Hrisztov, J.T. Recreational Factors Influencing the Choice of Destination of Hungarian Tourists in the Case of Bulgaria. Sustainability 2023, 15, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postelnicu, C.; Dabija, D.-C. Romanian Tourism: Past, Present and Future in the Context of Globalization. Ecoforum 2018, 14, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ioniţă, R.; Pîndiche, E. Comparative Study Between the Romanian Seaside Tourism and Bulgarian Seaside Tourism. “Ovidius” Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2011, XI, 642–645. [Google Scholar]

- Băbăț, A.-F.; Mazilu, M.; Niță, A.; Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Grigore, M. Tourism and Travel Competitiveness Index: From Theoretical Definition to Practical Analysis in Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, M.; Hapenciuc, C.-V.; Arionesei, G. Online Visibility–Opportunity to Increase Tourism Competitiveness. The Case of the Hotels on the Romanian Seaside Versus the Bulgarian Seaside. In Proceedings of the STRATEGICA 2016–Opportunities and Risks in the Contemporary Business Environment, Bucharest, Romania, 20–21 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BlueFlag.bg. Available online: http://www.blueflag.bg/blueflag_12.php (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- BlueFlag.ro. Available online: https://www.ccdg.ro/ (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Haller, A.P. Tourism Industry Development in the Emerging Economies of Central and Eastern Europe (Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania). SEA-Pract. Apl. Sci. 2016, IV, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Zbuchea, A.; Dinu, M. Evolutions of International Tourism in Romania and Bulgaria. In the Critical Issues in Global Business: Lessons from the Past, Contemporary Concerns and Future Trends; International Management Development Association—IMDA: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Aivaz, K.A.; Juganaru, I.D.; Juganaru, M. Comparative Analysis of the Seasonality in the Monthly Number of Overnight Stays in Romania and Bulgaria, 2005–2016. In Proceedings of the International E-Conference: Enterprises in the Global Economy, Birmingham, UK, 27–29 October 2017; pp. 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, A.-P.; Tacu Hârșan, G.-D. Longitudinal Analysis of Sustainable Tourism Potential of the Black Sea Riparian States Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croitoru, M. Tourism Competitiveness Index-An Empirical Analysis Romania vs. Bulgaria. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2011, 18, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Min, H. Enjoyment or Indulgence: What Draws the Line in Hedonic Food Consumption? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türker, N.; Süzer, Ö. Tourists’ Food and Beverage Consumption Trends in the Context of Culinary Movements: The Case of Safranbolu. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, N. Romania versus Bulgaria. Black Sea Tourism. Case Study. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2011, XI, 926–928. [Google Scholar]

- MEDIAFAX. Seven Cars Belonging to Romanians Who Were at Sea in Bulgaria Disappeared in Front of the Hotels. Available online: https://www.mediafax.ro/social/sapte-masini-ale-unor-romani-aflati-la-mare-in-bulgaria-au-disparut-din-fata-hotelurilor-6079612.MEDIAFAX2010 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Digi24. The Car Theft Network, Destroyed in Bulgaria; Prosecutor: They Can Steal Any Car in Minutes. In 4 Hours It Was Completely Dismantled. Available online: https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/externe/ue/retea-de-furturi-auto-destructurata-in-bulgaria-procuror-pot-fura-orice-masina-in-cateva-minute-in-4-ore-era-dezmembrata-complet-2267155.Digi24.ro28.02.20232023 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Chersulich Tomino, A.; Perić, M.; Wise, N. Assessing and Considering the Wider Impacts of Sport-Tourism Events: A Research Agenda Review of Sustainability and Strategic Planning Elements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing Creative Places: The Role of Creative Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.J.; Ferreira, J.J.M.; Almeida, A.; Parra-Lopez, E. Tourist Events and Satisfaction: A Product of Regional Tourism Competitiveness. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 943–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alén, E.; Losada, N.; de Carlos, P. Profiling the Segments of Senior Tourists Throughout Motivation and Travel Characteristics. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarratt, D.; Gammon, S. ‘We Had the Most Wonderful Times’: Seaside Nostalgia at a British Resort. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, G.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Exploring Familiarity and Destination Choice in International Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juganaru, I.D. The Beach Extention Project in Mamaia Resort, on the Romanian Black Sea Coast: Certain Benefits, but also Numerous Tourist Complaints. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2021, XXI, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, L.; Dodds, R. Blue Flag Beach Certification: An Environmental Management Tool or Tourism Promotional Tool? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakci, S.; Aras, S.; Yetimoglu, S. (Eds.) Global & Emerging Trends in Tourism; Necmettin Erbakan University Press: Konya, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bethmann, C. “Clean, Friendly, Profitable”? In Tourism and the Tourism Industry in Varna, Bulgaria; LIT: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Hirt, S.; Slaev, A. Planning In Market Conditions: The Performance Of Bulgarian Tourism Planning During Post-Socialist Transformation. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2012, 29, 318–334. [Google Scholar]

- Slavov, M.; Palupi, R. Over-Tourism: The Untold Story of The Rise of Sunny Beach, Bulgaria. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Tour. Events 2019, 3, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsee, K. The Red Riviera Gender, Tourism, and Postsocialism on the Black Sea; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johann, M.; Anastassova, L. The Perception of Tourism Product Quality and Tourist Satisfaction: The Case of Polish Tourists Visiting Bulgaria. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 8, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, I.; Castro, C. Online Travel Agencies: Factors Influencing Tourist Purchase Decision. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2019, 15, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Years) | Occupation | Income (EUR/Month) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 14% | blue collar job | 28% | ≤800 | 54% |

| 25–34 | 9.5% | white collar job | 46% | 800–900 (national average) | 38% |

| 35–44 | 15% | students | 14% | ||

| 45–64 | 49% | retired | 12% | >1000 | 8% |

| 65 and over | 12.5% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, L.; Albă, C.D.; Mazilu, M.; Șoșea, C. ‘Should I Go or Should I Stay?’ Why Do Romanians Choose the Bulgarian Seaside for Their Summer Holiday? Sustainability 2023, 15, 11802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511802

Popescu L, Albă CD, Mazilu M, Șoșea C. ‘Should I Go or Should I Stay?’ Why Do Romanians Choose the Bulgarian Seaside for Their Summer Holiday? Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511802

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Liliana, Claudia Daniela Albă, Mirela Mazilu, and Cristina Șoșea. 2023. "‘Should I Go or Should I Stay?’ Why Do Romanians Choose the Bulgarian Seaside for Their Summer Holiday?" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511802

APA StylePopescu, L., Albă, C. D., Mazilu, M., & Șoșea, C. (2023). ‘Should I Go or Should I Stay?’ Why Do Romanians Choose the Bulgarian Seaside for Their Summer Holiday? Sustainability, 15(15), 11802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511802