Gender Mainstreaming in Miraa Farming in the Eastern Highlands of Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gender and Division of Labor

2.2. Gender and Decision Making

2.3. Access to Extension Services by Gender

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

3.3. Sampling Procedure

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic and Socio-Economic Characterization of Farmers

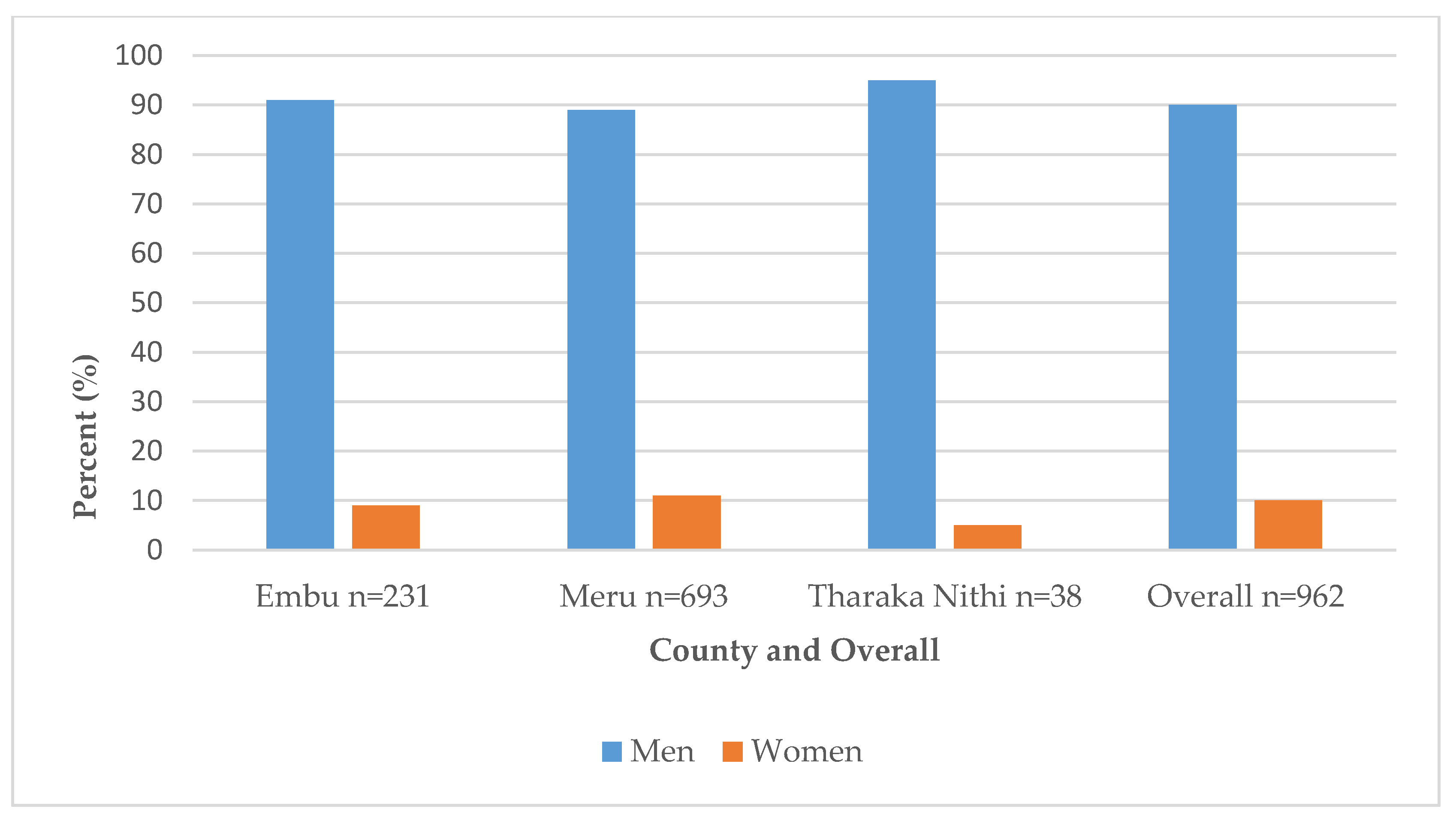

4.1.1. Sex of the Household Heads per County

4.1.2. Age of Household Head

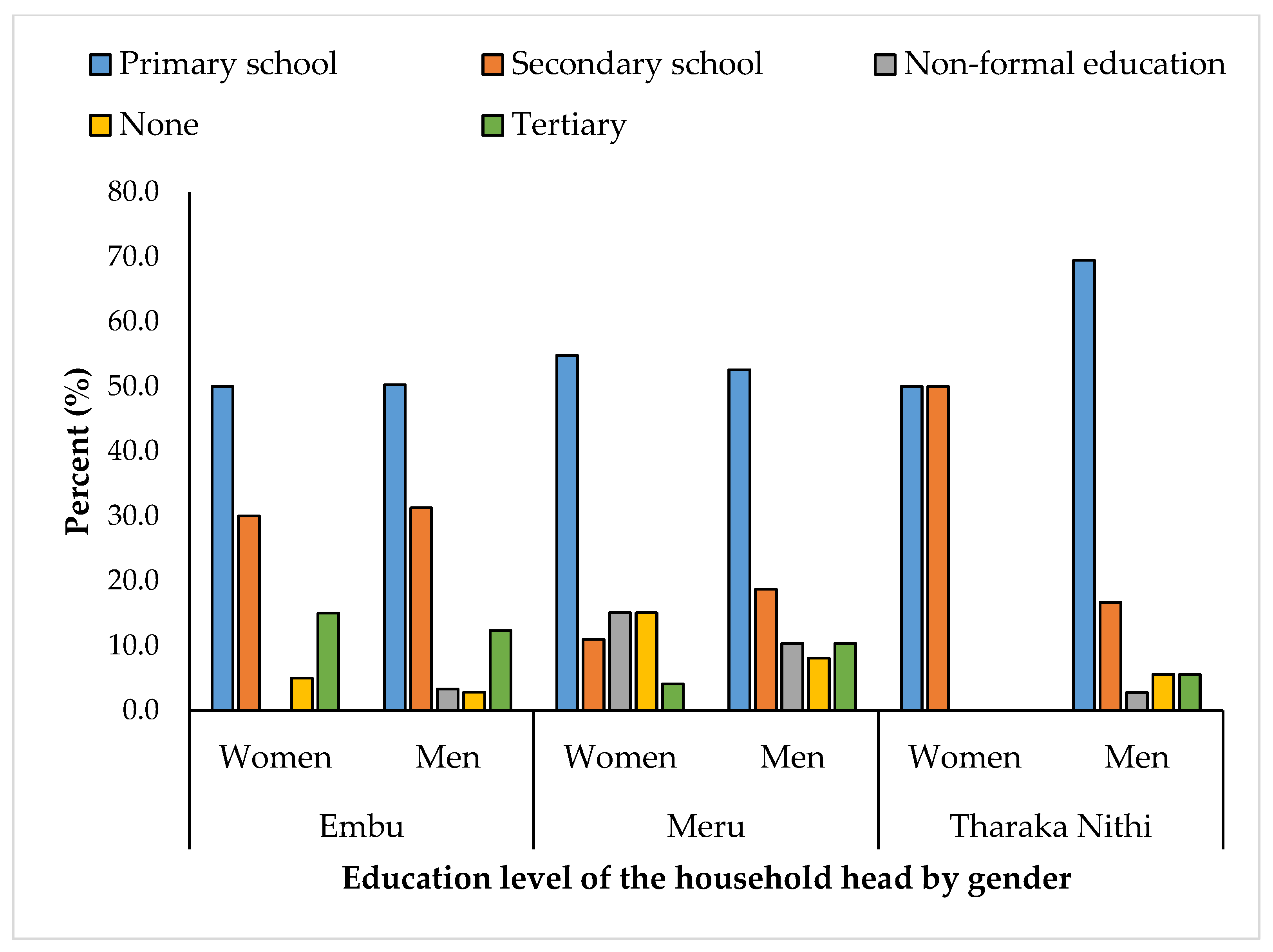

4.1.3. Education Level of the Household Head by Gender

4.2. Decision Making by Gender on Miraa Production and Marketing Domains

4.3. Division of Labor by Gender Categories in Miraa Production Activities

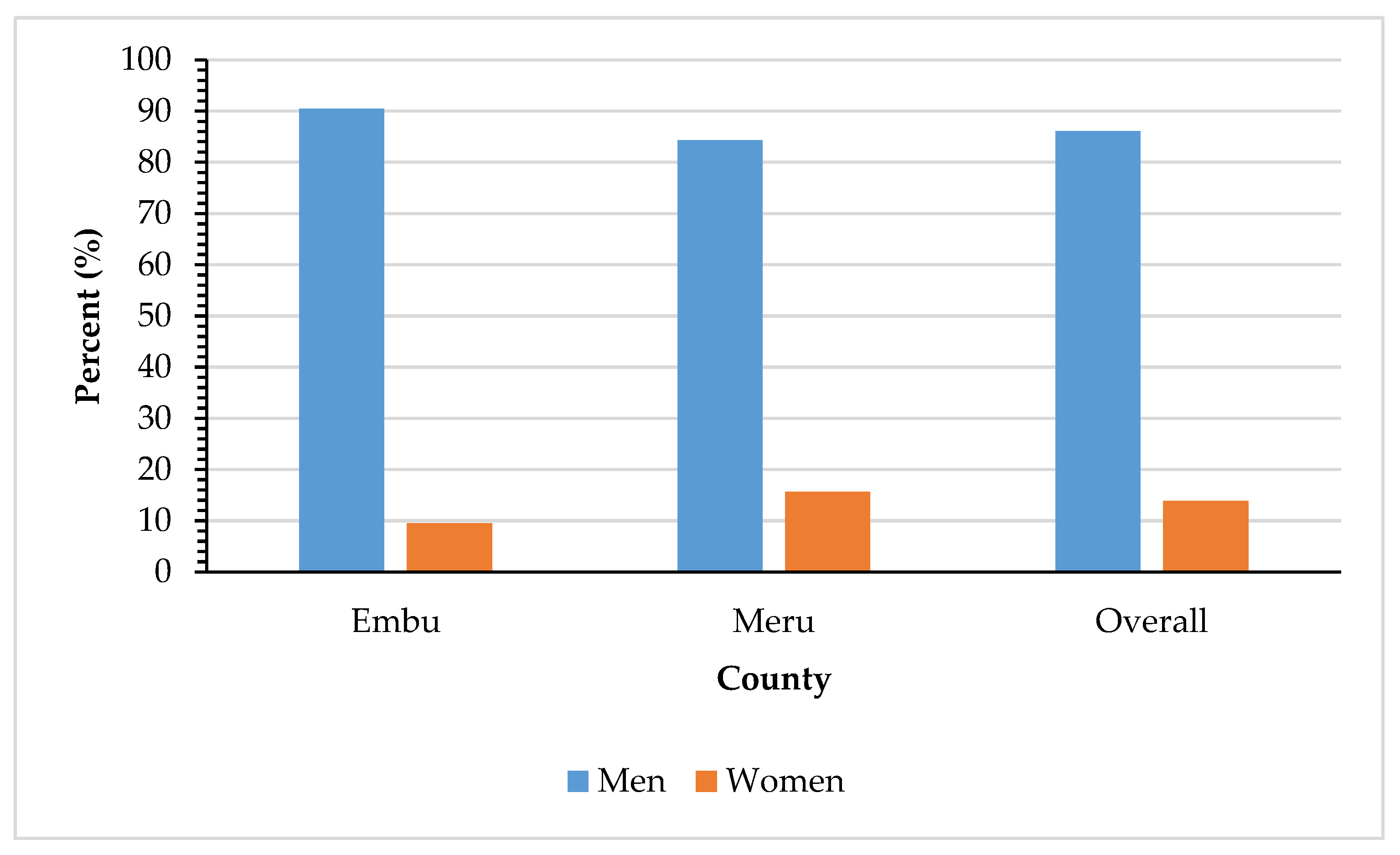

4.4. Access to Extension Services by Gender

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Council for Science and Technology Republic of Kenya. Catha Edulis (Miraa): A Detailed Review Focusing on Its Chemistry, Health Implication, Economic, Legal, Social, Cultural, Religious, Moral Aspects and Its Cultivation; National Council for Science and Technology: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; Volume 40.

- Republic of Kenya. Report of the Taskforce on the Development of Miraa Industry in Kenya; Government Printer: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017.

- Bain, C.; Ransom, E.; Halimatusa’diyah, I. ‘Weak Winners’ of Women’s Empowerment: The Gendered Effects of Dairy Livestock Assets on Time Poverty in Uganda. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A.; Theis, S. Women in agriculture: Four myths. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 16, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyabaro, V.; Mburu, J.; Hutchinson, M. Factors enabling the participation of women in income sharing among banana (musaspp.) producing households in South Imenti, Meru County, Kenya. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2019, 23, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, R.; Mwaseba, D.L.; Njarui, D.; Moeletsi, M.; Magalasi, M.; Mutimura, M.; Hundessa, F.; Aamodt, J.T. Feminization of African Agriculture and the Meaning of Decision-Making for Empowerment and Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyer, S. Closing the Gender Gap in Agriculture. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2016, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, B. Smallholder Horticultural Commercialization: Gender Roles and Implications for Household Well-being in Kenya. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Agricultural Economist, Milan, Italy, 9–14 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Peterman, A.; Quisumbing, A.; Seymour, G.; Vaz, A. The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index. World Dev. 2013, 52, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.; Qaim, M. Gender, agricultural commercialization, and collective action in Kenya. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambua, S.; Birachi, E.; Gichangi, A.; Kavoi, J.; Njuki, J.; Mutua, M.; Ugen, M.; Karanja, D. Influence of productive resources on bean production in male- and female-headed households in selected bean corridors of Kenya. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrienne, W. Applying the Harvard Gender Analytical Framework: A Case Study from a Guatemalan Maya-Mam Community. Can. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Stud. 2014, 22, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R. Men’s Crops? Women’s Crops? The Gender Patterns of Cropping in Ghana. World Dev. 2002, 30, 1987–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubi, J.; Njarui, M.G.; Murage, A.; Gatheru, M.; Thuranira, E. Gender Inequality in Dairy Farming Technologies in the Central and Eastern Highlands of Kenya. In Proceedings of the 4th MWECAU International Conference, Moshi Kilimanjaro, Tanzania, 25–29 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, C. The “Good Wife”: Struggles over Resources in the Kenyan Horticultural Sector. J. Dev. Stud. 2001, 37, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boserup, E. Women’s Role in Economic Development; St. Martin Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miriti, L.; Wamue-Ngare, G.; Masiga, C.; Miruka, M.K.; Maina, I.N. Gender Concerns in Banana Production and Marketing: Their Impacts on Resource Poor Households in Imenti South District, Kenya. J. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 7, 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sender, J.; Smith, S. Poverty, Class and Gender in Rural Africa: A Tanzanian Case Study; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Farm Africa. Gender and Coffee Value Chain in Kanungu, Uganda; Farm Africa: Kampala, Uganda, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, S.; Bezaury, J.A.; Mutersbaugh, T. Gender equity in fairtrade–organic coffee producer organizations: Cases from Mesoamerica. Geoforum 2010, 41, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, H. Gender Role Allocation in Selected Coffee Postharvest Activities. J. Ekon. Pembang. Univ. Muhammadiyah Surak. 2013, 14, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dalsgaard, K.; Masaeus, C.; Orfanos, G.; Wehde, M. Gender and Agriculture: Gendered economic strategies: Division of labor, responsibilities and controls within households in Nyeri District, Kenya. In Proceedings of the International Research on Food Security, Natural Resources Management and Rural Development, Vienna, Austria, 18–21 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneri, M.; Holmes, R. When Being More Productive Still Doesn’t Pay: Gender Inequality and Socio-Economic Constraints in Ghana’s Cocoa Sector. In Proceedings of the FAO-IFAD-ILO Workshop on Gaps, Trends and Current Research in Gender Dimensions of Agricultural and Rural Employment, Rome, Italy, 31 March–2 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, J.; Watts, M. Disciplining Women? Rice, Mechanization, and the Evolution of Mandinka Gender Relations in Senegambia. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 1991, 16, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Braun, J.; Bouis, H.; Kennedy, E. Agricultural Commercialization, Economic Development and Nutrition: Conceptual Framework. Agricultural Commercialization, Economic Development and Nutrition; Von Braun, J., Kennedy, E., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press for the International Food Policy Research Institute: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.K. Adoption of Hybrid Maize in Zambia: Effects on Gender Roles, Food Consumption, and Nutrition. Food Nutr. Bull. 1995, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiundu, K.M.; Oniang’o, R.K. Marketing African Leafy Vegetables: Challenges and Opportunities in the Kenyan Context. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2007, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.; Martha, M.; Wekundah, J.; Ndungu, F.; Odondi, J.A.; Oyure, A.O.; Andima, D.; Kamau, M.; Ndubi, J.; Musembi, F.; et al. Agricultural Knowledge and Information Systems in Kenya: Implication for Technology Dissemination and Development; Agricultural Research and Extension Network Paper; Agricultural Research and Extension Network: London, UK, 2000; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Melesse, B. A Review on Factors Affecting Adoption of Agricultural New Technologies in Ethiopia. J. Agric. Sci. Food Res. 2018, 9, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Gatheru, M.; Njarui, D.M.G.; Gichangi, E.M.; Ndubi, J.M.; Murage, A.W.; Gichangi, A.W. Status and Factors Influencing Access of Extension and Advisory Services on Forage Production in Kenya. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 39, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C. How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? The case of improved maize technology in Ghana. Agric. Econ. 2001, 25, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Mekonnen, H.; Spurling, D. Raising the Productivity of Women Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa; Discussion Paper 230; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A. Improving Women’s Agricultural Productivity as Farmers and Workers; Discussion Paper 37; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis; Harper & Row and John Whetherhill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- De Vaus, D.A. Research Design in Social Research; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ogada, M.J.; Mwabu, G.; Muchai, D. Farm Technology Adoption In Kenya: A Simultaneous Estimation of Inorganic Fertilizer and Improved Maize Variety Adoption Decisions. Agric. Food Econ. 2014, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiritu, S.W.; Kassie, M.; Shiferaw, B. Are There Systematic Gender Differences in The Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Intensification Practices? Evidence from Kenya. Food Policy 2014, 49, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubi, J. Getting Partnerships to Work: A Technography of the Selection, Making and Distribution of Improved Planting Material in the Kenyan Central Highlands. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, C.A.K.; Jayathilake, W.; Wickramasuriya, H.V.A.; Dissanayake, U.; Wasala, W.M.C.B. A Review on Factors Affecting Technology Adoption in Agricultural Sector. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 17, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchird, R.; Sasaki, N.; Abe, I. Influencing Factors of the Adoption of Agricultural Irrigation Technologies and the Economic Returns: A Case Study in Chaiyaphum Province, Thailand. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J.H.; Wang, J.H.; Liou, Y.C. Farmers’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Adoption of Smart Agriculture Technology in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Park, H.K. Factors Affecting the Acceptability of Technology in Health Care Among Older Korean Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Cross-Sectional Study Adopting the Senior Technology Acceptance Model. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeru, L.; Mwangi, J. Influence of Khat (Miraa) on Primary School Dropout Among Boys in Meru County, Kenya. J. US-China Public Adm. 2013, 10, 727–737. [Google Scholar]

- Ng’Ang’A, J.G.; Mwela, E.M. Influence of Khat Farming on Learners Attendance in Primary and Secondary Schools in Kangeta Sub-Location. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2020, 8, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, M.; Kariuki, S. Factors Determining Adoption of New Agricultural Technology by Smallholder Farmers in Developing Countries. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 6, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Women | Joint | Men | Chi-Square | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Land use | 77 | 8.7 | 140 | 15.8 | 668 | 75.5 | 21.85 | <0.001 *** |

| Which varieties to grow | 74 | 8.8 | 79 | 9.4 | 686 | 81.8 | 21.89 | <0.001 *** |

| Use of cash generated | 78 | 8.9 | 199 | 22.8 | 595 | 68.2 | 55.58 | <0.001 *** |

| Who and number of farm laborers to hire | 97 | 11.2 | 145 | 16.7 | 626 | 72.1 | 28.11 | <0.001 *** |

| Price to sell | 70 | 8.1 | 97 | 11.2 | 696 | 80.6 | 17.45 | <0.001 *** |

| Whether to borrow money and from where | 72 | 8.7 | 208 | 25.0 | 551 | 66.3 | 74.06 | <0.001 *** |

| How to use borrowed money | 70 | 8.4 | 121 | 14.5 | 645 | 77.2 | 88.96 | <0.001 *** |

| Which inputs to buy | 70 | 8.4 | 121 | 14.5 | 645 | 72.2 | 58.86 | <0.001 *** |

| Use of income from generated from the crop | 69 | 8.3 | 230 | 27.7 | 531 | 64 | 68.64 | <0.001 *** |

| Activities | Gender Category | Embu (%) | Meru (%) | Tharaka Nithi (%) | Overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planting | n = 419 | n = 1023 | n = 65 | n = 1507 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 2.2 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 36.3 | 53.8 | 24.6 | 47.6 | |

| Men above 35 | 32.9 | 25.9 | 52.3 | 29.0 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 16.5 | 12.7 | 12.3 | 13.7 | |

| Women above 35 | 13.8 | 3.9 | 7.7 | 6.8 | |

| Chi-square | 181.0 | 1277.8 | 73.7 | 1523.3 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Weeding | n = 463 | n = 1146 | n = 99 | n = 1708 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 35.6 | 36.8 | 25.3 | 35.8 | |

| Men above 35 | 30.0 | 16.4 | 33.3 | 21.1 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 2.5 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 17.3 | 27.9 | 17.2 | 24.4 | |

| Women above 35 | 16.2 | 12.4 | 20.2 | 13.9 | |

| Chi-square | 296.1 | 627.5 | 47.1 | 883.0 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Severe pruning | n = 255 | n = 58 | n = 10 | n = 323 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 10.0 | 0.9 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 39.2 | 41.4 | 10.0 | 38.7 | |

| Men above 35 | 43.9 | 44.8 | 40.0 | 44.0 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 0.3 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 9.0 | 6.9 | 20.0 | 9.0 | |

| Women above 35 | 7.8 | 3.4 | 10.0 | 7.1 | |

| Chi-square | 113.2 | 52.0 | 4.4 | 367.4 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | 0.493 | <0.001 *** | |

| Normal pruning | n = 388 | n = 876 | n = 73 | n = 1337 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 38.4 | 51.7 | 30.1 | 46.7 | |

| Men above 35 | 38.1 | 38.5 | 41.1 | 38.5 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 12.4 | 5.7 | 12.3 | 8.0 | |

| Women above 35 | 10.8 | 1.8 | 13.7 | 5.1 | |

| Chi-square | 232.8 | 1327.8 | 55.8 | 1674.0 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Pest control | n = 373 | n = 491 | n = 70 | n = 934 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 41.8 | 55.4 | 38.6 | 48.7 | |

| Men above 35 | 42.4 | 29.3 | 44.3 | 35.7 | |

| Women 10 to 17 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | |

| Girls 18 to 35 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 5.7 | 9.2 | |

| Women above 35 | 7.0 | 3.5 | 11.4 | 5.5 | |

| Chi-square | 309.9 | 702.1 | 31.1 | 1172.8 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Manure application | n = 415 | n = 1074 | n = 65 | n = 1554 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 2.7 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 31.6 | 35.4 | 33.8 | 34.3 | |

| Men above 35 | 31.8 | 20.3 | 36.9 | 24.1 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 2.9 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 18.8 | 24.1 | 15.4 | 22.3 | |

| Women above 35 | 17.3 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 13.7 | |

| Chi-square | 137.5 | 492.5 | 46.8 | 737.6 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Fertilizer application | n = 49 | n = 252 | n = 37 | n = 338 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 1.8 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 34.7 | 43.3 | 29.7 | 40.5 | |

| Men above 35 | 20.4 | 19.4 | 35.1 | 21.3 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 24.5 | 27.4 | 16.2 | 25.7 | |

| Women above 35 | 20.4 | 6.7 | 16.2 | 9.8 | |

| Chi-square | 2.7 | 209.1 | 12.1 | 241.7 | |

| p-value | 0.445 | <0.001 *** | 0.017 * | <0.001 *** | |

| Foliar application | n = 37 | n = 138 | n = 44 | n = 219 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 43.2 | 61.6 | 38.6 | 53.9 | |

| Men above 35 | 29.7 | 29.7 | 36.4 | 31.1 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 10.8 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 6.4 | |

| Women above 35 | 16.2 | 1.4 | 20.5 | 7.8 | |

| Chi-square | 9.4 | 252.3 | 13.3 | 302.5 | |

| p-value | 0.025 * | <0.001 *** | 0.004 ** | <0.001 *** | |

| Harvesting | n = 554 | n = 1093 | n = 100 | n = 1747 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 2.9 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 33.2 | 57.7 | 35.0 | 48.7 | |

| Men above 35 | 29.4 | 20.2 | 37.0 | 24.1 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 20.4 | 13.2 | 8.0 | 15.2 | |

| Women above 35 | 16.8 | 2.3 | 18.0 | 7.8 | |

| Chi-square | 184.7 | 1494.4 | 79.0 | 1658.7 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Sorting | n = 448 | n = 1025 | n = 102 | n = 1575 | |

| Boys 10 to 17 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 | |

| Men 18 to 35 | 41.1 | 58.0 | 36.3 | 51.8 | |

| Men above 35 | 27.2 | 20.8 | 34.3 | 23.5 | |

| Girls 10 to 17 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 1.7 | |

| Women 18 to 35 | 19.4 | 13.2 | 11.8 | 14.9 | |

| Women above 35 | 11.6 | 2.1 | 17.6 | 5.8 | |

| Chi-square | 342.4 | 1433.2 | 18.1 | 1731.7 | |

| p-value | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001*** | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ndubi, J.; Murithi, F.; Thuranira, E.; Murage, A.; Kathurima, C.; Gichuru, E. Gender Mainstreaming in Miraa Farming in the Eastern Highlands of Kenya. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512006

Ndubi J, Murithi F, Thuranira E, Murage A, Kathurima C, Gichuru E. Gender Mainstreaming in Miraa Farming in the Eastern Highlands of Kenya. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512006

Chicago/Turabian StyleNdubi, Jessica, Festus Murithi, Elias Thuranira, Alice Murage, Cecilia Kathurima, and Elijah Gichuru. 2023. "Gender Mainstreaming in Miraa Farming in the Eastern Highlands of Kenya" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512006

APA StyleNdubi, J., Murithi, F., Thuranira, E., Murage, A., Kathurima, C., & Gichuru, E. (2023). Gender Mainstreaming in Miraa Farming in the Eastern Highlands of Kenya. Sustainability, 15(15), 12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512006