Abstract

Prior research regarding communication audits within organizations depicts a general understanding of various aspects of the communication process that augment productivity. The present study aimed at validating a newly developed scale that measures internal communication maturity within organizations through an employee-centric approach rather than a management-centric one. The present study employs a cross-sectional survey research design. A total of 2071 employees (94.4% male; 5.6% female) from the logistic industry across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were approached through convenience sampling. Based on the literature review and results derived from interviews, 16 items were generated with a 5-point Likert response format. Results indicated the measure is reliable and valid. Reliability analysis showed good alpha reliability coefficients (>0.75) between total internal communication satisfaction and its subscales (awareness, appreciation, relationship, engagement and maturity). The correlation matrix from EFA revealed the presence of coefficients of 0.3 and above, indicating the data is fit for factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable model-data fit of the five-factor model. Data were collected only from the logistics industry; however, data can be gathered from other industries as well. Furthermore, cross-sectional data are used in the current study; therefore, they cannot be used to infer a causal relationship. The present study will be broadly helpful in diagnosing specific communication areas and formulating recommendations for improvement. The instrument will be worthwhile in communication audits of organizations.

1. Introduction

Evaluation of an organization’s impalpable assets is important and has been carried out for a long time. Among the means of evaluation, communication is considered important [1]. The appropriate skills, as well as knowledge of communication formats, awareness of information flow constraints, knowledge of the factors influencing communication processes, and, most importantly, access to instruments that facilitate message exchange, are all necessary for effective organizational communication [2]. Internal and external communication are the two main categories of organizational communication methods [3]. Internal communication refers to correspondence within the organization about ideas, as well as transmitting information either upward or downward, whereas external communication refers to the transposing of information from the organization to the outside and vice versa [4].

Internal communication shows the commitment of the management to the process of communication with employees. Therefore, the role of management in setting the company’s communication strategies to align with organizational goals is important [5], as internal communication strategies improve an organization’s performance and promote a positive relationship between employees and the organization [6]. This helps companies to make the right decisions and adopt the right strategies within the given time frame and budget [7]. Additionally, communication helps in facilitating innovation performance within the organization [8]. The existing literature accentuates the importance of internal communication and of identifying higher levels of performance, as well as services that are correlated with communication inside firms; consequently, creating communication, along with social capital, is entrenched in organizational connections [9,10]. Moreover, several recent studies have highlighted the positive impact of effective communication in promoting employee engagement, job performance [11], job satisfaction [12], employee achievement [13], and work enthusiasm in enhancing employee performance [14]. Internal communication has also been linked to increased levels of job satisfaction and employee performance [15].

In today’s increasingly competitive marketplace, organizations are realizing the importance of measuring and evaluating their communication practices. This process of identifying strengths and weaknesses alongside problems is referred to as a communication audit [16,17]. Downs et al. [18] elucidated the usage of a communication audit as a quality check of communication within the organization, encompassing different techniques for data collection. The prior literature examined internal communication with other organizational outcomes such as employee engagement and happiness in the workplace [19], productivity [20], and presenteeism [21]. However, there is limited existing knowledge and literature data on the reliability and validity of the auditing techniques. Moreover, the existing data focus on and explore the concepts of internal communication from the organization, management, or employer perspective; therefore, this study will focus on fulfilling these gaps by trying to address the reliability and validity of auditing techniques and exploring internal communication, its concept and significance from the employee’s perspective, to gain a better understanding of different aspects of communication within the organizations.

Furthermore, at present, organizations are transforming themselves into employee-centric, and are making policies that cater to employees’ needs, expectations, and interests [22]. Therefore, it is important to study communication practices within the organization from the employees’ perspective and to fill this research gap. The employee-centric approach helps to inculcate the feeling of empowerment in the workplace by listening to and valuing their input [23]. Therefore, reviewing the literature and existing scales, five primary dimensions were considered [24], i.e., awareness, appreciation, relationship, engagement, and maturity, from the employee perspective, followed by the development of a new scale that can play an effective role in measuring the communication satisfaction of employees [25].

To enhance the employee’s sense of organizational membership, it is important to disseminate knowledge about the organization’s future goals and strategies to its employee [26]. Hence employees became aware of the organization’s values and expectations for their routine tasks, and consequently, their corporate identity is enhanced [27]. Furthermore, organizations allow their employees to be aware of the various news within the organization or coming from outside, which provides a sense of responsibility and commitment [28]. Consequently, it is essential for organizations to educate employees about their rights and privileges, fostering a sense of empowerment and satisfaction [29]. Along with this, appreciation of employees at each level is essential to keep an employee motivated. This appreciation may be from the immediate boss and higher management in tangible and intangible forms [30]. Being acknowledged either by colleagues, managers, or higher authorities within the organization leads to strong relationships, not only with colleagues but with the organization [31]. Healthy and strong relationships within the organizations lead to engagement [32]. Gray and Ladilaw [33] described internal communication satisfaction as a predominant aspect in evaluating an organization’s communication effectiveness.

Researchers [34,35,36,37,38] concluded that communication satisfaction has different aspects to measure, ranging from information received by employees, upward and downward communication, frequency of interaction with colleagues, job satisfaction, and the modality of communication, as well as management personnel, and the organizational climate and commitment. The present study aimed at measuring communication satisfaction through the employees’ perspectives. For this, a measure consisting of five dimensions of ICS (awareness, appreciation, relationship, engagement, and maturity), derived from the literature, has been developed. Moreover, current research intends to establish the psychometric properties of the newly developed scale that can be used as an auditing index within organizations.

2. Theoretical Overview

2.1. Internal Communication

Internal communication is defined as an organization’s group members working together to collect information, consequently increasing employee engagement [3]. It does not only refer to the dissemination of information and messages within a company [39], but efficacious management of change requires effective internal communication [40], and it is crucial for evaluating internal communication [9]. A cohesive workplace is created by excellent internal communication, which enables individuals and teams to operate effectively and efficiently, enhances a person’s sense of belonging inside the organization, and motivates employees [41]. Every employee in a business is part of a team or group, and internal communication assists in resolving issues that arise inside those groups [3]. Employee relationships are strengthened, mutual respect and trust are developed, and the proper information flow required for the business’s successful operation is ensured [42].

Researchers believe that effective communication has a significant impact on an organization’s performance, productivity, and external customer orientation [43,44,45]; however, scholars and communication professionals find it difficult to isolate the function of organizational communication [46]. Based on the employees’ satisfaction and performance, Erjavec et al. [47] assert that businesses with an effective internal communication strategy achieve greater customer satisfaction and loyalty [48]. Moreover, several studies highlight the importance of internal communication during times of crisis and uncertainty. A study carried out by Qin and Men [49] indicated the positive effects of internal communication on employees’ well-being during the pandemic. Similarly, Puyod and Charoensukmongkol [50] conducted a study in Philippine universities during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that formalizing crisis communication mitigated the negative impact of workplace rumors on the trust of employees and their job satisfaction. Moreover, effective communication strategies have been linked to reducing perceived job insecurity among flight attendants during the pandemic by maintaining employee well-being during times of crisis [51]. Another study carried out by Nekmat and Kong [52] found that online rumors negatively affect attitudes toward the organization during times of uncertainty. The researchers suggested the importance of effective crisis communication strategies, specifically proactive communication, for addressing such rumors and for ensuring that accurate and timely information is provided to the stakeholders. Similarly, Marsen [53] highlights the significance of effective communication in managing organizational crises by encouraging proactive communication strategies and transparent communication to maintain organizational reputation and stakeholder trust. Therefore, employees should be given the tools they need to regulate quality and solve problems by being empowered, encouraged, trained, and supported. Without a means of internal communication, staff members choose to propagate rumors to support the company.

The area of internal communication comprises marketing, public relations, human resources, and employer branding [54]. Internal communication is an organization’s regular business activity, and includes meetings with superiors, updates on project groups, and presentations where management speak. It also includes newsletters, messages on the intranet, and emails [55]. Kalla [56] has identified four distinct domains of internal communication: (a) business communication implicating employees’ skills; (b) management communication encompassing management capabilities for communication; (c) corporate communication comprising formal communication; and (d) organizational communication. Safarova and Jenny [57] classified internal communication by stakeholder groups according to four dimensions: internal line management, internal team peer, internal project peer, and internal corporate. An organization usually evaluates its own communication systems and identifies the gaps in existing patterns [46].

2.2. Communication Audit

Organizations employ communication audits to gauge the effectiveness of their communication systems. During the audit process, it transpires that the evaluation of satisfaction with internal communication (ICS) is actuated in some aspect [10]. Ćorić et al. [58] explained ICS as a derivative of the socio-emotional impacts of communication interaction. Thus, communication audits mostly emphasized processes over employee needs or content that influence organizational identity and engagement [9]. Audits typically pay close attention to who is communicating with whom, the issues being addressed, the amount of information delivered and received, the level of trust, and the effectiveness of working relationships [9,18].

Communication audits within businesses can be a useful tool to collect data and diagnose communication-related and other issues, as well as an approach for employees to engage in reflective learning [59]. An internal communications audit can have several benefits, such as fewer strikes, reduced absenteeism, better services and goods, higher levels of innovation, and low costs [54]. Communication, financial, and accounting audits involve collecting information (diagnostic phase) that appraises a series of episodes to recognize major trends. In the development of a control system (the prescriptive phase), a system is developed to regulate the flow of information and to simultaneously relate communication practices with publicly stated standards (the accountability phase), which compares the end results with current practice [10].

During a communication audit, there are various data collection techniques such as surveys, interviews, diary studies, network analyses, ECCO analysis, and critical incident techniques (CIT) used for auditing purposes [60]. The survey is widely utilized across the board. Downs [18] identified 500 survey instruments used in organizational communication research and categorized them into three categories that assess organizational communication at the macro, communication-satisfaction, and organizational-outcome level. The need to use communication satisfaction as an auditing tool is growing by the day, as it not only provides insight into the strengths and weaknesses of the communication system, but also identifies areas for improvement through the design and implementation of new strategies [61].

2.3. Internal Communication Satisfaction as Communication Audit

Communication satisfaction is largely measured in communication audits since the facet of internal communication is perceived as a primary indicator of organizational health. While Abdien [62] claimed that low communication satisfaction results in higher absenteeism and employee turnover, Davidescu et al. [63] also determined that employees who are content with communication have a bigger impact on organizational effectiveness. Reduced stress, increased job satisfaction, and greater dedication are further effects of better communication. An effective working relationship is a result of satisfactory communication [10]. While Ćorić et al. [58] found a strong positive link between life satisfaction and ICS, Verčič and Vokić [64] find that ICS is positively connected to perceived organizational support, employee engagement, and employer desirability. Further studies are required to examine the connection between ICS and organizational results, because communication satisfaction has drawn greater attention in recent decades [36].

Researchers proposed CS as unidimensional, indicating a second-order factor structure [65,66], which is bidimensional [67], and multidimensional [58]. Already developed instruments used to evaluate ICS are management/centric, although CSQ measures CS from employees’ perspective by asking a large number of questions [68]. However, there is a need to develop psychometrically sound employee-centric short instruments to measure aspects of communication satisfaction. Thus, the present study aimed at validating the newly developed scale that measures internal communication satisfaction within organizations from the employee’s perspective, which will be beneficial in understanding and assessing the various aspects of communication and formulating strategies and recommendations for further improvement. The newly formed scale measures five aspects on which internal communication can be assessed, which include employees’ awareness, appreciation, relationship, engagement, and internal communication maturity. It will be helpful in identifying the problematic areas within the organization’s internal communication and benefit the organization in employing new strategies to increase the communication satisfaction of the employees, consequently enhancing job satisfaction and productivity.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

A total of 2071 employees working in the logistics industry across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were approached through a convenience sampling technique. Participants were approached online. The concerned logistic firms were identified, and a proper invitation was sent through the human resources department. For those firms who showed their interest, a link containing the questionnaire was sent to them, which was disseminated to the employees. This dissemination process relied on existing connections within the firms, allowing for the expansion of the participant pool. Participation in the study was voluntary; therefore, participants who were interested in participating filled out the online questionnaire. Participants’ anonymity was assured.

Among participants, 95.44% were men, whereas 5.6% were women. Almost 72.9% were working in non-managerial positions and 1.6% were working in managerial positions. A total of 92% of participants have more than 3 years of work experience in their current organization. Demographic details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant’s characteristics (N = 2071).

3.2. Measure

For assessing internal communication satisfaction, a new scale comprised of 16 items has been developed following the guidelines of Boateng et al. [69], who described three phases of scale development spanning nine steps.

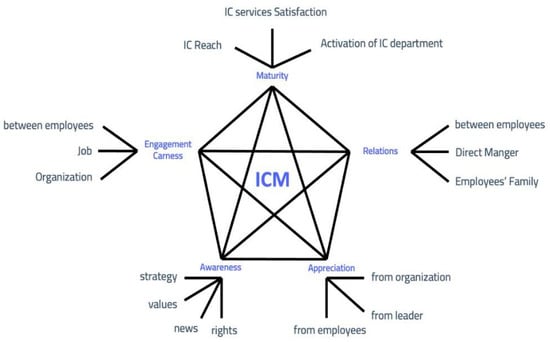

Phase I: items were generated, and content validity was assessed. For item generation, Guttman’s facet analysis was used [70,71]. The facet method involves mapping and describing items according to practice and theory. In the scale development procedure, both deductive and inductive methods were followed [72,73]. The deductive method includes a literature review of the construct which clarifies the nature and variety of the target tool, and, through the inductive method, interviews from the targeted population were carried out [74,75]. After the identification, the scope and range of the content domain through the literature review, existing scales, and interviews from the stakeholders, the 16 items encompassing five subdomains (awareness, engagement, relations, appreciation, and maturity) mentioned in Figure 1 were spawned.

Figure 1.

ICM and its sub-domains.

Afterward, items were reviewed by the five subject experts to assure content validity [76]. Subject experts were requested to respond to each item as to whether it corresponds with the conceptualized construct by selecting “Yes”/“No”. It was a priori decided that an item would be removed if more than 50% of experts responded “no”, indicating that it does not adequately represent its relevant element, or if more than 50% of nonexperts responded “no”, indicating that it is not clearly worded [69]. Almost 100% of results were obtained on all 16 items with “Yes” responses from subject experts.

After item development and expert review, scale items were assessed through cognitive interviews with participants having similar characteristics to the targeted population. Cognitive interviews were carried out in line with the guidelines given by Willis [77]. For this purpose, 8 individuals were interviewed. These interviews helped in framing statements, grammar, and response choices (5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)].

According to Boateng et al. [69], phases 2 and 3 of the scale development consisted of data analysis techniques. In phase 2, pre-testing led to pilot testing, in which a questionnaire was initially administered to 464 logistic industry employees, as suggested by Guadagnoli and Velicer [78]. At this stage, item reduction pertaining to factor extraction was carried out, whereas Phase 3 aimed to confirm the extracted factors.

3.3. Data Analysis

Boateng et al. [69] provided guidelines for data analysis techniques as part of the scale development phases. As a consequence of pilot testing, item reduction was carried out to retain the parsimonious, functional, and internally consistent items in the final scale [79]. There are several methods for item reduction; among them, inter-item correlation is a widely used method [80]. The current study utilizes the same method, and the criterion for the correlation coefficient was set (>0.30) to retain the item in scale [81].

Then, exploratory factor analysis was carried out through factor extraction. In this, an optimal number of factors usually considered as domain or subscales can be extracted. These domains or subscales are comprised of a particular set of items. This extraction can be performed by deriving latent factors that indicate shared variance in response among items [82]. Results of factor extraction concentrated on estimates of factor loadings. With factor analysis, items with factor loadings or slope coefficients that are below 0.30 are reflected as inadequate, as they contribute <10% variation of the latent construct measured [81]. However, not a single item loading was less than 0.30. Afterward, an evaluation of reliability and validity was carried out. The test of dimensionality was carried out through confirmatory factor analysis. Brown [83] suggested performing confirmation of factors on a new sample. This allows systematic comparison, based on a priori systematic procedures. These techniques involve a chi-square test of exact fit, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.06), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI ≥ 0.95), and comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.95). For each systematic procedure, cutoff thresholds described by Yu [84] have been used in the present study. Afterward, reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha, and validity assessment was employed by model fitting and assessing AVE and MSV. The value of AVE must be greater than MSV.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 describes the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. It includes gender, job level, location and sector of the organization, and age in terms of duration of joining the current organization. The table shows that most of the sample (94.4%) consisted of male participants, whereas only 5.6% of participants were female. Furthermore, it indicates that 72.9% of participants were not serving as employees, whereas only 1.6% were serving in executive management.

4.2. Reliability Analysis

Table 2 demonstrates descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for the scale and its sub-scales. Internal communication satisfaction total and its subscales (awareness, appreciation, relationship, engagement and maturity) showed good alpha reliability coefficients (>0.75); the threshold for Cronbach’s alpha is described by Tavakol [85] as well as by McNeish [86]. Moreover, the table indicates that the absolute values of skewness and kurtosis ranging from −0.779 to −1.365 and 0.056 to 1.964, respectively, are in the recommended range of normal distribution i.e., +2 to −2 [87].

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Estimates for the scale and its subscales (N = 2071).

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The suitability of the data for factor analysis was assessed through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [88]. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first performed unrotated, using maximum possibility extraction and eigenvalues > 1. Additionally, we performed EFA with promax rotation and enforced a five-factor solution to test the theoretical structure of the ICSQ.

Results indicate that one factor explained over 54.21% of the variance indicative of the significant common method bias [89]. However, the correlation matrix (Table 3) revealed the presence of coefficients of 0.3 and above, indicating the data are fit for factor analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.951, representing the fact that the sample was adequate, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity gave a p-value of <0.001. Initially, EFA showed a one-factor structure based on eigenvalues > 1. Additionally, EFA was performed with promax rotation with an enforced five-factor solution. Table 4 indicates the factor loadings of ICSQ.

Table 3.

Inter-item Correlation Matrix of ICSQ (N = 464).

Table 4.

Factor loadings of ICSQ (N = 464).

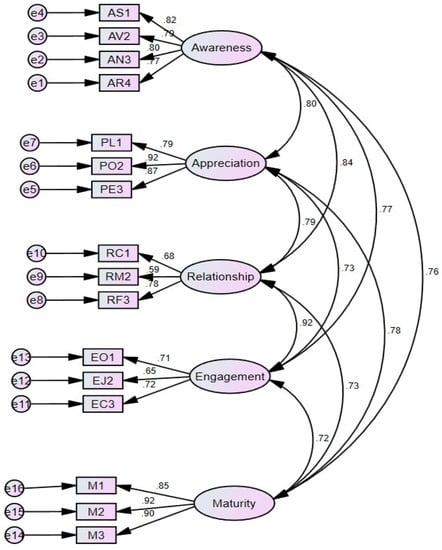

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 5 represents the results of the confirmatory factor analysis of the ICSQ. The 5-factor model shows an acceptable fit of data, with the model being significant (p < 0.01). NFI, CFI, and TLI are close to the 0.09 criterion, with PCFI meeting the >0.5 criteria, and RMSEA meeting the <0.10 criterion [90,91].

Table 5.

Summary of 1st order CFA (N = 2071).

Figure 2 showed 5 confirmed factors are (1) awareness of strategy, values, news, and rights; (2) appreciation involving praise from leader and organization to employees, as well as from employees to the organization; (3) relationship between employees, their immediate boss, and employee family to the organization; (4) engagement with other colleagues, job and corporation; and (5) maturity, involving active internal communication, and satisfaction with it and its reach.

Figure 2.

CFA of internal communication questionnaire (1st Order).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to determine the psychometric properties comprising reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the ICSQ. As shown in Table 6, average variance extracted (AVE) values were not greater than the criteria of 0.50 [90,92]. Therefore, convergent validity was assessed by examining the factor loadings of the scale items on their respective constructs. According to Hair et al. [93], standardized factor loadings of 0.40 or greater are considered acceptable, accounting for at least 16% of the variance in the corresponding factor for a newly developed measure.

Table 6.

Psychometric properties including reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the ICSQ (1st Order).

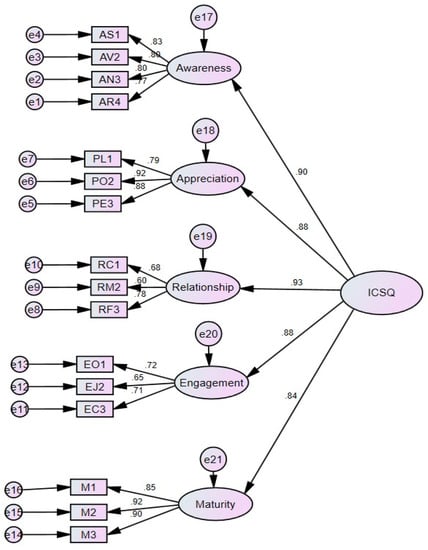

Discriminant validity was tested in two different ways, proposed by Henseler et al. [93] and Voorhees et al. [94]. First, the square root of the average variance extracted AVE values for each scale should be greater than the construct’s respective correlation with all other factors [95]. Secondly, the average variance of a factor should be greater than the variance which is shared with all other factors, meaning the average variance (AVE) extracted should be greater than the maximum shared variance (MSV)- [90]. The evidence of discriminant validity ended up with poor discriminant validity estimates. However, to deal with this issue of discriminant validity, Gaskin (2015) and Hair et al. (2010) suggested the conduction of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Hence, to improve the psychometric properties, second-order CFA has been carried out (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

CFA of internal communication questionnaire (2nd Order).

The 5-factor model showed an improved fit of data in second-order CFA (Table 5), with the model being significant (p < 0.01). NFI, CFI, and TLI are close to the 0.09 criterion, with PCFI meeting the >0.5 criterion, and RMSEA meeting the <0.10 criterion [90,91]. Furthermore, it shows improved composite reliability (CR = 0.95), and the value of AVE improved to 0.79.

5. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that internal communication satisfaction, like other measures, can be used as a reliable and valid tool for measuring communication systems within an organization [96]. Overall, the scale exhibited satisfactory psychometric properties. Factor analysis identified a 5-factor model fit; however, validation estimates showed a smaller AVE value (0.480) than the MSV (0.845), contrary to assumptions [90]. Therefore, a second-order confirmatory analysis was performed to show that the fit of the model improved and that the model became one-dimensional as suggested by researchers [33,66,67]. Additional analysis showed good internal consistency of total scales and subscales (p < 0.001). The subscales yielded (1) awareness about strategies, news, rights, and values; (2) appreciation involving praise from the leader and organization to employees, as well as from employees to the organization; (3) the relationship between employees, their immediate boss, and employee family to the organization; (4) engagement with other colleagues, job and corporation; and (5) maturity, involving active internal communication, and satisfaction with it and its reach.

Being aware of updated information (what is happening within the workplace) and one’s own rights, as well as organizational values, is important in evaluating communication satisfaction. Almost all scales of communication satisfaction explore the dimension of awareness [68]. Awareness of one’s own rights along with organizational values and needs as well as expectations enhances employees’ trust in the organization, and consequently has positive effects and encourages engagement within the organization [97]. Moreover, it gives a sense of being valued and helped in developing organizational identity [98]. This organizational identity can be achieved when employees align their own goals with the strategic direction of the employer and analyze how their tasks will contribute to organizational success [99].

Along with this, the appreciation and feedback employees received from colleagues as well as managers also increased satisfaction [100,101]. Appreciation received for one’s contribution motivates employees to perform better [98]. Henceforth, employees’ feelings of being appreciated for their tasks not only make a good purposeful team but also increase task engagement, and foster trust as well as respect, which leads to employee growth, ultimately contributing to retention [102]. The appreciation employees receive, either from the immediate boss or colleagues, strengthens their relationships with each other within the organization and provides a supportive environment for work [103]. Within supportive, comfortable environments, employees are likely to engage in open communication that results in active engagement. Employee engagement is considered an important indicator of satisfaction [104,105].

It can be concluded that all subscales are significant aspects of communication satisfaction, and are essential for measuring it. Therefore, almost all scales have questions related to these constructs [69]. During the communication audit of an organization, the employer may be aware of the issues prevailing inside the firm. After diagnosing the problem, one can intervene with the dimension and toil for the solution [46].

Henceforth, the organization may understand previous, current, and future communication practices that enable companies to assess their goals, value, reach, and satisfaction [101]. It identifies the value of communication in allocating resources astutely by recognizing information gaps and channels. Therefore, a communication audit allows organizations to proceed through developing trust and commitment. It also involves collecting feedback from employees, which helps in devising activities for improvement.

Limitations and Future Implications

Some limitations of the current study are as follows: firstly, despite the satisfactory sample size, the study sample comes from one business area only (logistics industry), mainly comprising men. The potential sample bias implies that to generalize the study’s results to other business areas and industries, as well as to other countries and geographic areas, the study has to be replicated in other contexts. Moreover, it is better to collect data from both genders, for better generalizability.

Another limitation is assessing internal communication satisfaction with the employee orientation rather than management; it is important to consider both aspects in future research. The newly developed scale will assess the employees’ perception of communication effectiveness. Moreover, it will also help in identifying the areas of improvement in the organizational communication system and help the organization redefine its goals by obtaining continuous feedback on the aspects mentioned of internal communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.J.; Methodology, M.I.J. and H.A.B.A.; Software, R.A.; Validation, R.A.; Formal Analysis, R.A. and M.A.L.; Investigation, M.I.J. and H.A.B.A.; Resources, M.I.J.; Data Curation, H.A.B.A.; Writing—Original Draft, All authors; Writing—Reviewing and Editing, R.A.; Supervision, M.I.J. and R.A.; Project Administration, M.I.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Committee of the College of Business Administration, King Saud bin Abdul Aziz University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (9 March 2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data output files from the analysis are available from corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Kalogiannidis, S. Impact of effective business communication on employee performance. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth, N.; Puspitawaty, P.D.; Santosa, P.; Gintings, A. The Effectiveness of Organizational Communication in Improving the Performance of Public and Private School Committees. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst. (BIRCI-J.) Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 20465–20474. [Google Scholar]

- Vorina, A.; Simonič, M.; Vlasova, M.A. An Analysis of the Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Employee Engagement. Econ. Themes 2017, 55, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankosic, M.; Ivetic, P.; Mikelic, K. Managing internal and external Communication in a Competitive Climate via EDI concept. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 2, 1–6. Available online: https://www.iaras.org/iaras/journals/caijoc/managing-internal-and-external-communication-in-a-competitive-climate-via-edi-concept (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Santos, M.J. “Searching for Gold” with Sustainable Human Resources Management and Internal Communication: Evaluating the Mediating Role of Employer Attractiveness for Explaining Turnover Intention and Performance. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, H.; Sahi, A.; Farasat, M. The roles of supervisor support, employee engagement and internal communication in performance: A social exchange perspective. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2023, 28, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, A.-M.; Dumitrascu, D.D. The measurement and evaluation of the internal communication process in project management. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. Ser. 2013, 22, 1563–1572. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mark_Neal/publication/256432141_Can_Business_Education_Change_Management_Practices_in_Non-Western_Societies/links/02e7e522860eae971f000000/Can-Business-Education-Change-Management-Practices-in-Non-Western-Societies.pdf#page=1563 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Rahimnia, F.; Molavi, H. A model for examining the effects of communication on innovation performance: Emphasis on the intermediary role of strategic decision-making speed. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 1035–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, S.S.-A. Organizational Identity Change: Impacts on Hotel Leadership and Employee Wellbeing. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 40, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Ćorić, D.S.; Vokić, N.P. Measuring internal communication satisfaction: Validating the internal communication satisfaction questionnaire. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2021, 26, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongton, P.; Suntrayuth, S. Communication satisfaction, employee engagement, job satisfaction, and job performance in higher education institutions. Abac J. 2019, 39, 90–110. Available online: https://repository.au.edu/handle/6623004553/22537 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Sharma, P.R. Organizational Communication: Perceptions of Staff Members’ Level of Communication Satisfaction and Job Satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, East Tennessee State University, Johnson, TN, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/f31842d173cdf860cec002e24c7067eb/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Pratama, S. Effect of Organizational Communication and Job Satisfaction on Employee Achievement at Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS). Binjai City. 2019. Available online: https://www.ijrrjournal.com/IJRR_Vol.7_Issue.11_Nov2020/IJRR0073.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Lantara, A. The effect of the organizational communication climate and work enthusiasm on employee performance. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulachai, W.; Narkwatchara, P.; Siripool, P.; Vilailert, K. Internal communication, employee participation, job satisfaction, and employee performance. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2018), Chonburi, Thailand, 1 March 2018; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mandiwana, A.R.; Barker, R. Measuring integrated internal communication: A South African case study. Communitas 2022, 27, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, I. Instruments for organizational communication assessment for Japanese care facilities. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2017, 22, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, C.W.; DeWine, S.; Greenbaum, H.H. Measures of organizational communication. In Communication Research Measures; Rubin, R.B., Palmgreen, P., Sypher, H.E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalić, D.; Milić, B.; Stanković, J. Internal communication and employee engagement as the key prerequisites of happiness. Joy 2020, 5, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Vokić, N.P. Engaging employees through internal communication. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan, N.A.M.; bin Mohamad, S.J.A.N.; Tengku, T.E. Managing presenteeism among academicians through effective internal communication. SEARCH J. Media Commun. Res. (SEARCH) 2022, I4, 151–166. Available online: https://fslmjournals.taylors.edu.my/wp-content/uploads/SEARCH/SEARCH-2022-SpecialIssue-ICOMS2021/SJ_SI-ICOMS_Full-Issue.pdf#page=160 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Sala, E.; Mayoral, J.M.; García-Soto, G.; Mazariegos, A. Employee Centricity: Discover How to Improve Your Employee Experience. [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://content.meta4.com/en/employee-centricity-talent-management (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Ruck, K.; Welch, M. Valuing internal communication; management and employee perspectives. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D.I. Constructing Validity: New Developments in Creating Objective Measuring Instruments. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špoljarić, A.; Verčič, D. The Effects of Social Exchange Quality Indicators on Employee Engagement Through Internal Communication. In (Re) Discovering the Human Element in Public Relations and Communication Management in Unpredictable Times; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023; Volume 6, pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari, G.; Alkurdi, B.; Alshurideh, A.; Alrowwad, A. Investigating the impact of communication satisfaction on organizational commitment: A practical approach to increase employees’ loyalty. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2017, 9, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermol, V.; Širca, N.T. Communication, company mission, organizational values, and company performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2018, 238, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, M. Don’t just tell employees organizational changes are coming-Explain why. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 2–5. Available online: https://erstrategies.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Don%E2%80%99t-Just-Tell-Employees-Organizational-Changes-Are-Coming-%E2%80%94-Explain-Why.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Taheri, R.H.; Miah, M.S.; Kamaruzzaman, M. Impact of Working Environment on Job Satisfaction. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2020, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.A.; Men, L.R.; Ferguson, M.A. Examining the effects of internal communication and emotional culture on employees’ organizational identification. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2021, 58, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, M.; von Platen, S.; Simonsson, C.; Falkheimer, J. Expanding the scope of strategic communication: Towards a holistic understanding of organizational complexity. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2018, 12, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.R. Paradigm shift in employee engagement—A critical analysis on the drivers of employee engagement. Int. J. Inf. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 32–46. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/5ef444cae975e8d20475386c9df33df4/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2032142 (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Gray, J.; Laidlaw, H. Improving the measurement of communication satisfaction. Manag. Commun. Q. 2004, 17, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, R.; Roebuck, D.B. Exploring cultural influence on managerial communication in relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and the employees’ propensity to leave in the insurance sector of India. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2016, 53, 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Špoljarić, A. Managing internal communication: How the choice of channels affects internal communication satisfaction. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T. The impact of employee engagement, organisational support and employer branding on internal communication satisfaction. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Men, L.R. Redefining the link between internal communication and employee engagement. Public Relat. Rev. 2023, 49, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, P.; Downs, C.; Degroote, S.; Vandijck, D.; Tobback, E.; Delesie, L.; Mariman, A.; De Veugele, M.; Verhaeghe, R.; Cambré, B.; et al. Intraorganizational communication and job satisfaction among Flemish hospital nurses: An exploratory multicenter study. Workplace Health Saf. 2018, 66, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, A. Understanding Organizational Change and Internal Communication. Eur. J. Manag. Mark. Stud. 2022, 4, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Verčič, A.T.; Verčič, D.; Špoljarić, A. Internal Communication and Employer Brands; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sawagvudcharee, O.; Yolles, M. Inside out with Knowledge Management toward Internal Communication Facilitating Transformational Change Efficiency. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2022, 6, 1–13. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4117111 (accessed on 7 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Chikazhe, L.; Nyakunuwa, E. Promotion of perceived service quality through employee training and empowerment: The mediating role of employee motivation and internal communication. Serv. Mark. Q. 2022, 43, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.A.M.; Hurtado, S.R.F. Internal communication issues in the firms: Does it affect the productivity. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Tran, T.B.H. Internal marketing, employee customer-oriented behaviors, and customer behavioral responses. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, O.A. The role of communication in enhancing employees organizational commitment. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 9, 1109–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R.B.; Palmgreen, P.; Sypher, H.E. Communication Satisfaction Questionnaire. In Routledge eBooks; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, K.; Arsenijević, O.; Starc, J. Satisfaction with Managers’ Use of Communication Channels and Its Effect on Employee-Organisation Relationships. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2018, 23, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.J.; Anwar, G.; Gardi, B.; Jabbar Othman, B.; Mahmood Aziz, H.; Ali Ahmed, S.; Abdalla Hamza, P.; Burhan Ismael, N.; Sorguli, S.; Sabir, B.Y. Business communication strategies: Analysis of internal communication processes. J. Humanit. Educ. Dev. 2021, 3, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.S.; Men, L.R. Exploring the impact of internal communication on employee psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of employee organizational trust. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 23294884221081838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyod, J.V.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Effects of workplace rumors and organizational formalization during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of universities in the Philippines. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2021, 26, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P.; Suthatorn, P. How managerial communication reduces perceived job insecurity of flight attendants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2022, 27, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmat, E.; Kong, D. Effects of online rumors on attribution of crisis responsibility and attitude toward organization during crisis uncertainty. J. Public Relat. Res. 2019, 31, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsen, S. Navigating crisis: The role of communication in organizational crisis. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 57, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T. Internal communication with a global perspective. In The Global Public Relations Handbook; Sriramesh, K., Vercic, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Dynamics of symmetrical communication within organizations: The impacts of channel usage of CEO, managers, and peers. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 59, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, S.; Kartikawangi, D. Internal Communication in Building Organizational Culture and Organizational Branding of Government Institution. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Inclusive Business in the Changing World, Jakarta, Indonesi, 6–7 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarova, J.; Jenny, H. Appropriateness of Internal Communication Channels: A Stakeholder Approach. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:849639 (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Ćorić, D.S.; Vokić, N.P.; Verčič, A.T. Does good internal communication enhance life satisfaction? J. Commun. Manag. 2020, 24, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romenti, S.; Murtarelli, G.; Miglietta, A.; Gregory, A. Investigating the role of contextual factors in effectively executing communication evaluation and measurement: A scoping review. J. Commun. Manag. 2019, 23, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, K. Case study research. In Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner; Burkholder, G.J., Cox, K.A., Crawford, L.M., Hitchok, J., Eds.; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, J.K. The influence of internal communication satisfaction on employees’ organisational identification: Effect of perceived organisational support. J. Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdien, M. Impact of communication satisfaction and work-life balance on employee turnover intention. J. Tour. Theory Res. 2019, 5, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Apostu, S.A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work flexibility, job satisfaction, and job performance among Romanian employees—Implications for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Sung, Y. Shaping corporate character through symmetrical communication: The effects on employee-organization relationships. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 59, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, M.L. The conceptualization and measurement of interpersonal communication satisfaction. Hum. Commun. Res. 1978, 4, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manata, B.; Grubb, S. Conceptualizing leader–member exchange as a second-order construct. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 953860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, H.J.A.; Ramoo, V.; Chong, M.C.; Danaee, M.; Aljeesh, Y.I.; Rajeswaran, V.U. The Mediating Role of Work Satisfaction in the Relationship between Organizational Communication Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment of Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, C.W.; Hazen, M.D. A factor analytic study of communication satisfaction. J. Bus. Commun. 1977, 14, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziner, A.E. The Facet Analytic Approach to Research and Data Processing; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, L. A structural theory of intergroup beliefs and action. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1959, 24, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.S.C.; Hsieh, P.L. Assessing the self-service technology encounters: Development and validation of SSTQUAL scale. J. Retail. 2011, 87, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Measuring personal cultural orientations: Scale development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.A.; Lovler, R. Foundations of Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, G.B. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnoli, E.; Velicer, W.F. Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 103, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurstone, L. Multiple-Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T. Scale Construction and Development. Lecture Notes. Measurement and Quantitative Methods; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, T.; Marcoulides, G.A. Introduction to Psychometric Theory; Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McCoach, D.B.; Gable, R.K.; Madura, J.P. Instrument Development in the Affective Domain. School and Corporate Applications, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Testing Statistical Assumptions; Statistical Associates Publishing: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dziuban, C.D.; Shirkey, E.C. When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in Covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Vokić, N.P.; Ćorić, S. Development of the Internal Communication Satisfaction Questionnaire; Faculdade de Economia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, S.; Johnston, K.A.; Lane, A.; Beatson, A. A strategic employee attribute scale: Mediating role of internal communication and employee engagement. Public Relat. Rev. 2023, 49, 102320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, C.; Galvão, A.R.; Marques, C.S. How perceived organizational support, identification with organization and work engagement influence job satisfaction: A gender-based perspective. Admins Sci. 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.N. Exploring the role of strategic internal communication in organizational strategy execution. Public Relat. Rev. 2022, 48, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qerimi, G. Analysis of Top-Down Organizational Communication in Railway Companies in the Republic of Kosovo from the Employees’ Perspective. J. Media Res. 2019, 12, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, P.; Blot, S.; Degroote, S.; Vandijck, D.; Mariman, A.; Vanacker, T.; Peleman, R.; Verhaeghe, R.; Vogelaers, D. Communication satisfaction and job satisfaction among critical care nurses and their impact on burnout and intention to leave: A questionnaire study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018, 48, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Park, H. The impact of family-friendly corporate culture on employees’ behavior. J. Korea Ind. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 23, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.L.; Cross, R.L.; Parker, A. The Hidden Power of Social Networks: Understanding How Work Really Gets Done in Organizations; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, Z.M.; Sudin, S.; Shamsuddin, N. The influence of leadership style, personality attributes and employee communication on employee engagement. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 743. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/78dc030f320a5785f8f1ba432b8f4b6e/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=696409 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Špoljarić, A.; Verčič, A.T. Internal communication satisfaction and employee engagement as determinants of the employer brand. J. Commun. Manag. 2021, 26, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).