The Impact of Learning Organization on Intrapreneurship: The Case of Jordanian Pharmaceutics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Learning Organization

2.1.1. Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire (DLOQ) Developed by [18]

2.1.2. The Fifth Discipline Developed [22]

2.1.3. A Typology of the Idea of the Learning Organization Developed [29]

2.1.4. The Building Blocks Developed by [38]

2.2. The Relationship between Learning Organization and Different Concepts

2.2.1. Learning Organization and Employee’s Satisfaction, Job Involvement, and Commitment

2.2.2. Learning Organization and Knowledge Management

2.2.3. Learning Organization and Innovation

2.2.4. Learning Organization and Organizational Performance

2.3. Intrapreneurship

Intrapreneurship Dimensions

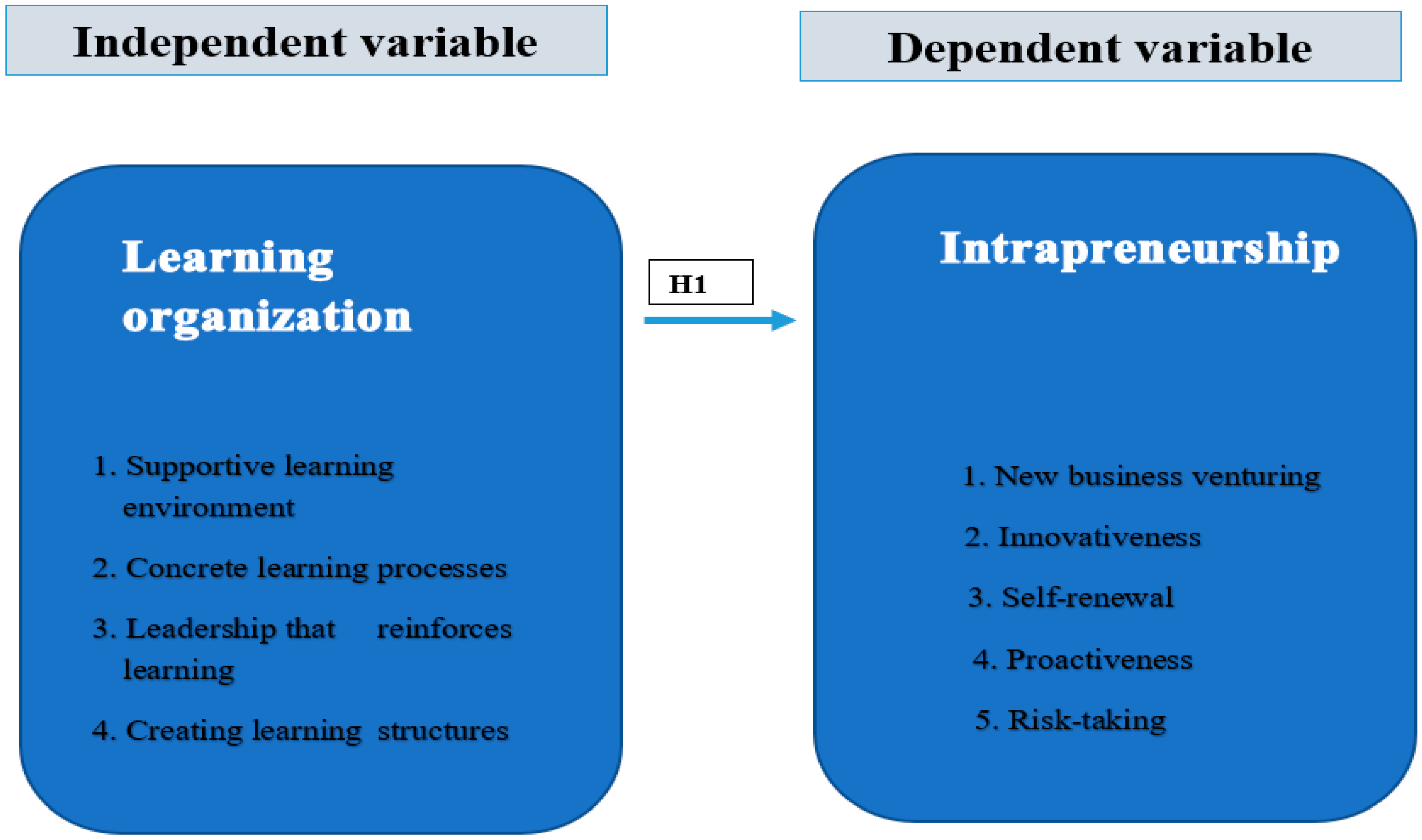

2.4. Hypothesis Development

Relationship between Learning Organization and Intrapreneurship

3. Methodology

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Normality Test

4.2. Reliability Test

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griego, O.V.; Geroy, G.D.; Wright, P.C. Predictors of learning organizations: A human resource development practitioner’s perspective. Learn. Organ. 2000, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowden, R.W. The learning organization and strategic change. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2001, 66, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D. Five years on—The organizational culture saga revisited. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2002, 23, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C.; Callahan, J.L. Fostering organizational performance: The role of learning and intrapreneurship. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B.; Hisrich, R.D. Intrapreneurship: Construct refinement and cross-cultural validation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 495–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H.H.; Jarillo, J.C. A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. In Entrepreneurship; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gapp, R.; Fisher, R. Developing an intrapreneur-led three-phase model of innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2007, 13, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.R. Personality traits and intrapreneurship: The mediating effect of career adaptability. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.A.N.; Simsek, Z.; Lubatkin, M.H.; Veiga, J.F. Transformational leadership’s role in promoting corporate entrepreneurship: Examining the CEO-TMT interface. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinha, N.; Srivastava, K.B.L. Association of Personality, Work Values and Socio-cultural Factors with Intrapreneurial Orientation. J. Entrep. 2013, 22, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto Felício, J.; Ribeiro Soriano, D.; Rodrigues, R.; Caldeirinha, V.R. The effect of intrapreneurship on corporate performance. Manag. Decis. 2021, 50, 1717–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Alvarez, C.; Turró, A. Organizational resources and intrapreneurial activities: An international study. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizarci-Payne, A.K. Intrapreneurship. Encycl. Sustain. Manag. 2020, 26, 25–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah, B.; Ward, A. Metamorphosis of intrapreneurship as an effective organizational strategy. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 11, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzeschi, L.; Bucci, O.; Fabio, A.D. High Entrepreneurship, Leadership, and Professionalism (HELP): A New Resource for Workers in the 21st Century. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, J.; Gupta, M.; Hassan, Y. Intrapreneurship to engage employees: Role of psychological capital. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 1525–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M. Intrapreneurship centric innovation: A step towards sustainable competitive advantage. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. 2016, 5, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, V.J.; Watkins, K.E. Demonstrating the value of an organization’s learning culture: The dimensions of the learning organization questionnaire. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2003, 5, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Chermack, T.J.; Kim, W. An Analysis and Synthesis of DLOQ-Based Learning Organization Research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2013, 15, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, T.M.; Yang, B.; Bartlett, K.R. The effects of organizational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to transfer learning and turnover intention. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2014, 15, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y.; Reese, S. A journey of collaborative learning organization research. Learn. Organ. 2018, 25, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Örtenblad, A. Senge’s many faces: Problem or opportunity? Learn. Organ. 2007, 14, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.M.; Baruch, Y. Learning organizations in higher education: An empirical evaluation within an international context. Manag. Learn. 2010, 43, 515–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiedrowski, P.J. Quantitative assessment of a Senge learning organization intervention. Learn. Organ. 2006, 13, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.C.; Lee, M.S. A study on relationship among leadership, organizational culture, the operation of learning organization and employees’ job satisfaction. Learn. Organ. 2007, 14, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Savarimuthu, A. Hospitals as Learning Organizations: An Explication through A Systems Model. Int. J. Manag. (IJM) 2015, 6, 573–584. [Google Scholar]

- Hoe, S.L. Digitalization in practice: The fifth discipline advantage. Learn. Organ. 2019, 27, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Organizational learning: A radical perspective. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2002, 4, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. On differences between organizational learning and learning organization. Learn. Organ. 2001, 8, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. A typology of the idea of learning organization. Manag. Learn. 2002, 33, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. The learning organization: Towards an integrated model. Learn. Organ. 2004, 11, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Toward a contingency model of how to choose the right type of learning organization. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2004, 15, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Odd couples or perfect matches? On the development of management knowledge packaged in the form of labels. Manag. Learn. 2010, 41, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A.; Koris, R. Is the learning organization idea relevant to higher educational institutions? A literature review and a “multi-stakeholder contingency approach”. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2014, 28, 173–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Towards increased relevance: Context-adapted models of the learning organization. Learn. Organ. 2015, 22, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. What does “learning organization” mean? Learn. Organ. 2018, 25, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D.A.; Gino, F. Is yours a learning organization? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Borge, B.H.; Filstad, C.; Olsen, T.H.; Skogmo, P.Ø. Diverging assessments of learning organizations during reform implementation. Learn. Organ. 2019, 25, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watkins, K.E.; Kim, K. Current status and promising directions for research on the learning organization. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2018, 29, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtenblad, A. Handbook of Research on the Learning Organization: Adaptation and Context; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dekoulou, P.; Trivellas, P. Measuring the Impact of Learning Organization on Job Satisfaction and Individual Performance in Greek Advertising Sector. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatane, S.E. Employee Satisfaction and Performance as Intervening Variables of Learning Organization on Financial Performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jahangir, M. Impact of learning organization on job satisfaction: An empirical study of telecommunication companies of Pakistan. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 10, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Suifan, T.S.; Allouzi, R.A.R. Investigating the impact of a learning organization on organizational performance: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Int. Bus. Manag. 2018, 12, 230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, D. Employees’ job involvement and satisfaction in a learning organization: A study in India’s manufacturing sector. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2019, 39, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, M.; Ilğan, A.; Uçar, H.İ. Relationship between Learning Organization and Job Satisfaction of Primary School Teachers. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2014, 6, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, S.M.; Dalimunthe, R.F.; Siahaan, E. The effect of learning organizations, achievement motivation through work environment as a moderating variable on the job satisfaction of temporary employees’ (non medical) in the administration service of North Sumatra University Hospital Medan, Indonesia. Eur. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2019, 3, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Chai, D.S.; Kim, J.; Bae, S.H. Job Performance in the Learning Organization: The Mediating Impacts of Self-Efficacy and Work Engagement. Perform. Improv. Q. 2018, 30, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngah, R.; Tai, T.; Bontis, N. Knowledge Management Capabilities and Organizational Performance in Roads and Transport Authority of Dubai. Mediat. Role Learn. Organ. Knowl. Process Manag. 2016, 23, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Marsick, V.J. Using the DLOQ to Support Learning in Republic of Korea SMEs. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2013, 15, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Moreno, A. Organizational learning, knowledge management practices and firm’s performance. Learn. Organ. 2015, 22, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. Impact of knowledge management on learning organization practices in India. Learn. Organ. 2011, 18, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.K.; O’brien, M.J. The Building Blocks of the Learning Organization. Training 1994, 31, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Al Saifi, S.A. Toward a Theoretical Model of Learning Organization and Knowledge Management Processes. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 15, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh; Shankar, R.; Narain, R.; Kumar, A. Survey of knowledge management practices in Indian manufacturing industries. J. Knowl. Manag. 2006, 10, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroño-Cerdán, A.L.; López-Nicolás, C. Innovation objectives as determinants of organizational innovations. Innovation 2017, 19, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.S.; Yao, C.Y.; Liou, D.M. The effects of knowledge interaction for business innovation. RD Manag. 2017, 47, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F.; Aravind, D. Managerial Innovation: Conceptions, Processes and Antecedents. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 8, 423–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganter, A.; Hecker, A. Configurational paths to organizational innovation: Qualitative comparative analyses of antecedents and contingencies. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, C.S.; Arif, A. Impact of organizational learning on organizational performance: Study. Int. J. Acad. Res 2011, 3, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Mrisha, G. Effect of Learning Organization Culture on Organizational Performance Among Logistics Firms in Mombasa County. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 5, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ratna, R.; Khanna, K.; Jogishwar, N.; Khattar, R.; Agarwal, R. Impact of learning organization on organizational performance in consulting industry. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2014, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, E.J.; Fitzsimmons, J.R. Intrapreneurial intentions versus entrepreneurial intentions: Distinct constructs with different antecedents. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 41, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burgers, J.H.; Covin, J.G. The contingent effects of differentiation and integration on corporate entrepreneurship. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, E.G.; Irwin, D.W. Fostering intrapreneurship: The new competitive edge. J. Bus. Strategy 1988, 9, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Naffziger, D.W.; Montagno, R.V. Implementing entrepreneurial thinking in established organizations. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 1993, 58, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R.M.; Richardson, L. Designing and running entrepreneurial vehicles in established companies—The Enter-Prize Program at Ohio Bell, 1985–1990. J. Bus. Ventur. 1991, 6, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badguerahanian, L.; Abetti, P.A. The rise and fall of the Merlin-Gerin Foundry Business: A case study in French corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushnitsky, G.; Lavie, D. How alliance formation shapes corporate venture capital investment in the software industry: A resource-based perspective. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2010, 4, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Espinosa, M.D.M.; Mohedano Suanes, A. Corporate entrepreneurship through joint venture. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.C. Intrapreneurship or entrepreneurship? J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camelo-Ordaz, C.; Fernández-Alles, M.; Ruiz-Navarro, J.; Sousa-Ginel, E. The intrapreneur and innovation in creative firms. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2011, 30, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Rees, P.; Murray, N. Turning entrepreneurs into intrapreneurs: Thomas Cook, a case-study. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 79, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, W.D.; Ginsberg, A. Guest editors’ introduction: Corporate entrepreneurship. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A. Environment, corporate entrepreneurship, and financial performance: A taxonomic approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B.; Hisrich, R.D. Clarifying the intrapreneurship concept. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2003, 10, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B. Intrapreneurship: A comparative structural equation modeling study. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2007, 107, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mokaya, S.O. Corporate entrepreneurship and organizational performance theoretical perspectives, approaches and outcomes. Int. J. Arts Commer. 2012, 1, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.W.; Rahman, N.; Abu Saleh, M.; Akhter, S. A Holistic Approach to Innovation and Fostering Intrapreneurship. Int. J. Knowl.-Based Organ. 2019, 9, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Organizational learning and entrepreneurship in family firms: Exploring the moderating effect of ownership and cohesion. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.A. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of a scale to measure firm entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Kimbu, A.N.; Lin, P.; Ngoasong, M.Z. Guanxi influences on women intrapreneurship. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Nasir, N.; Rehman, C.A. Intrapreneurship concepts for engineers: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations and agenda for future research. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valka, K.; Roseira, C.; Campos, P. Determinants of university employee intrapreneurial behavior: The case of Latvian universities. Ind. High. Educ. 2020, 34, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashami, F.M.; Nili, M.; Farahani, A.V.; Shaikh, N.; Dwibedi, N.; Madhavan, S.S. Entrepreneurial and Intrapreneurial Intentions of Student Pharmacists in Iran:The EIPQ Translation and Adaptation. Am. J. Pharm. Education. 2023, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Neessen, P.C.M.; De Jong, J.P.; Caniëls, M.C.J.; Vos, B. Circular purchasing in Dutch and Belgian organizations: The role of intrapreneurship and organizational citizenship behavior towards the environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Arfi, W.; Hikkerova, L. Corporate entrepreneurship, product innovation, and knowledge conversion: The role of digital platforms. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 56, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, S.; Vengrouskie, E.F.; Lloyd, R.A. Driving Organizational Innovation as a form of Intrapreneurship within the Context of Small Businesses. J. Strateg. Innov. Sustain. 2019, 14, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Serinkan, C.; Kaymakçi, K.; Arat, G.; Avcik, C. An Empirical Study on Intrapreneurship: In A Service Sector in Turkey. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 89, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franco, M.; Haase, H. Entrepreneurship: An organisational learning approach. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2009, 16, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, E.; García-Morales, V.J.; Martín-Rojas, R. Analysis of the influence of the environment, stakeholder integration capability, absorptive capacity, and technological skills on organizational performance through corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 14, 345–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Amado, J.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Nieves Perez-Arostegui, M. Information technology-enabled intrapreneurship culture and firm performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Audretsch, D.B. Clarifying the domains of corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 9, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, O.; Arun, K.; Begec, S. Intrapreneurship and expectations restrictions. Dimens. Empres. 2020, 18, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poduška, Z.; Nedeljković, J.; Nonić, D.; Ratknić, T.; Ratknić, M.; Živojinović, I. Intrapreneurial climate as momentum for fostering employee innovativeness in public forest enterprises. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 119, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, S.; Azizi, S.M.; Ziapour, A. Investigation of Relationship between Learning University Dimensions and Intrapreneurship. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haase, H.; Franco, M.; Félix, M. Organisational learning and intrapreneurship: Evidence of interrelated concepts. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 906–926b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, F.; Idris, K.; Ismail, I.A.; Uli, J.A.; Karimi, R. Learning organization and organizational performance: Mediation role of intrapreneurship. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 21, 547–555. [Google Scholar]

- Alipour, F.; Khairuddin, I.; Karimi, R. Intrapreneurship in learning organizations: Moderating role of organizational factors. J. Am. Sci. 2011, 7, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad, B.A.; Abbaszadeh, M.M.S.; Djavani, M. Entrepreneur learning organization: A functional concept for universities. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2011, 10, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, N.; Mohamad, A.; Noordin, F.; Ishak, N.A. Learning Organization and its Effect on Organizational Performance and Organizational Innovativeness: A Proposed Framework for Malaysian Public Institutions of Higher Education. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussein, N.; Omar, S.; Noordin, F.; Ishak, N.A. Learning organization culture, organizational performance and organizational innovativeness in a public institution of higher education in Malaysia: A preliminary study. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebora, T.C.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Theerapatvong, T.; Lee, S.M. Corporate entrepreneurship in the face of changing competition. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2010, 23, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpkan, L.; Bulut, C.; Gunday, G.; Ulusoy, G.; Kilic, K. Organizational support for intrapreneurship and its interaction with human capital to enhance innovative performance. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 732–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Covin, J.G. Diagnosing a firm’s internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekmat, L.; Chelliah, J. What are the antecedents to creating sustainable corporate entrepreneurship in Thailand? Contemp. Manag. Res. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, M.; Mustafa, M. Antecedents of Corporate Entrepreneurship in SMEs: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhardwaj, B.; Momaya, K. Drivers and enablers of corporate entrepreneurship: Case of a software giant from India. J. Manag. Dev. 2011, 30, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, R.; Adonisi, M. Antecedents of corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 43, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gursoy, A.; Guven, B. Effect of innovative culture on intrapreneurship. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eze, B.U.; Abdul, A.; Nwaba, E.K.; Adebayo, A. Organizational Culture and Intrapreneurship Growth in Nigeria: Evidence from Selected Manufacturing Firms. EMAJ Emerg. Mark. J. 2018, 8, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prexl, K.-M. The intrapreneurship reactor: How to enable a start-up culture in corporations. e i Elektrotechnik Und Informationstechnik 2019, 136, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalas, A.; Venskus, R. Interaction of learning organization and organizational structure. Eng. Econ. 2007, 53, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zehir, C.; Can, E.; Karaboga, T. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation to Firm Performance: The Role of Differentiation Strategy and Innovation Performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 210, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, J. From learning organisation to knowledge entrepreneur. J. Knowl. Manag. 2000, 4, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, G.; Del Vecchio, P.; Schiuma, G.; Passiante, G. Activating entrepreneurial learning processes for transforming university students’ idea into entrepreneurial practices. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennbrant, S.; Pilhammar Andersson, E.; Nilsson, K. Elderly Patients’ Experiences of Meeting with the Doctor. Res. Aging 2012, 35, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leufvén, M.; Vitrakoti, R.; Bergström, A.; Ashish, K.C.; Målqvist, M. Dimensions of Learning Organizations Questionnaire (DLOQ) in a low-resource health care setting in Nepal. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2015, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.-P.; Payne-Gagnon, J.; Fortin, J.-P.; Paré, G.; Côté, J.; Courcy, F. A learning organization in the service of knowledge management among nurses: A case study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, A.; Berensen, N.; Daniels, R. Creating a learning organization to help meet the needs of multihospital health systems. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2018, 75, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnuswamy, I.; Manohar, H.L. Impact of learning organization culture on performance in higher education institutions. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 41, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, S. Is the higher education institution a learning organization (or can it become one)? Learn. Organ. 2017, 24, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, T. The Non-Profit Sector, Government and Business: Partners in the dance of change—An Irish perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 2002, 4, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrai, K.; Farkas, F. Nonprofit Organizations from the Perspective of Organizational Development and Their Influence on Professionalization. Naše Gospod. Our Econ. 2016, 62, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejarski, A.M.; Potter, M.; Morrison, R.L. Organizational Learning in the Public Sector: Culture, Politics, and Performance. Public Integr. 2018, 21, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retna, K.S.; Ng, P.T. The application of learning organization to enhance learning in Singapore schools. Manag. Educ. 2016, 30, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubran, A.M. The Practicing Degree of Leadership Skills by School Principals in the Green line in Palestine in Light of Learning Organization and Organizational Culture. Int. J. Res. Educ. 2017, 41, 163–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniasih, N.; Abdullah, T.; Akbar, M. The effect of supervision, environmental work, training and learning organization to the managerial. Eff. Head High Sch. Priv. 2017, 1, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Field, L. Schools as learning organizations: Hollow rhetoric or attainable reality? Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2019, 33, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Watkins, S.; Yoon, S.W.; Kim, J. Examining schools as learning organizations: An integrative approach. Learn. Organ. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtoor, A.S.M.; Arshad, D.A.; Hassan, H. The impact of learning organization on knowledge transfer and organizational performance. J. Adv. Res. Des. 2017, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, P.; Garg, P. Learning organization and work engagement: The mediating role of employee resilience. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Tool Name | Dimensions |

|---|---|

| The Fifth Discipline [22] |

|

| Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire DLOQ [18] |

|

| A typology of the learning organization [32] |

|

| Three building blocks [38] |

|

| Concept/Author Name | Dimensions |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship [75] |

|

| Entrepreneurial posture [76] |

|

| Corporate entrepreneurship [77,84] |

|

| Entrepreneurial orientation [79,85] |

|

| Skewness | Kurtosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| Learning organization | −0.675 | 0.150 | 0.735 | 0.299 |

| Learning environment | −0.765 | 0.150 | 0.705 | 0.299 |

| Learning process and practices | −0.744 | 0.150 | 0.757 | 0.299 |

| Leadership | −0.758 | 0.150 | 0.291 | 0.299 |

| Continuous learning structures | −0.404 | 0.150 | 0.471 | 0.299 |

| Intrapreneurship | −0.714 | 0.150 | 10.339 | 0.299 |

| New business venturing | −0.539 | 0.150 | 0.997 | 0.299 |

| Innovativeness | −1.099 | 0.150 | 20.269 | 0.299 |

| Self-renewal | −0.764 | 0.150 | 0.793 | 0.299 |

| Proactiveness | −0.741 | 0.150 | 0.449 | 0.299 |

| Risk taking | −0.529 | 0.150 | 0.312 | 0.299 |

| Factors | Cronbach Alpha Coefficient | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|

| Supportive learning environment | 0.898 | 7 |

| Learning process and practices | 0.932 | 11 |

| Leadership that reinforces learning | 0.944 | 8 |

| Creating learning structures | 0.897 | 9 |

| Factors | Cronbach Alpha Coefficient | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|

| New business venturing | 0.890 | 3 |

| Innovativeness | 0.934 | 3 |

| Self-renewal | 0.940 | 4 |

| Proactiveness | 0.950 | 4 |

| Risk taking | 0.930 | 4 |

| R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F-Value | Sig | Standardized Beta | t-Value | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.741 | 0.548 | 0.541 | 78.345 | 0.000 | |||

| Supportive learning environment | −0.091 | −1.634 | 0.103 | |||||

| Concrete learning processes and practices | 0.425 | 6.367 | 0.000 | |||||

| Leadership that reinforces learning | 0.298 | 4.326 | 0.000 | |||||

| Creating learning structure | 0.170 | 3.077 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ashal, N.; Masa’deh, R.; Twaissi, N.M. The Impact of Learning Organization on Intrapreneurship: The Case of Jordanian Pharmaceutics. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612211

Ashal N, Masa’deh R, Twaissi NM. The Impact of Learning Organization on Intrapreneurship: The Case of Jordanian Pharmaceutics. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612211

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshal, Najwa, Ra’ed Masa’deh, and Naseem Mohammad Twaissi. 2023. "The Impact of Learning Organization on Intrapreneurship: The Case of Jordanian Pharmaceutics" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612211

APA StyleAshal, N., Masa’deh, R., & Twaissi, N. M. (2023). The Impact of Learning Organization on Intrapreneurship: The Case of Jordanian Pharmaceutics. Sustainability, 15(16), 12211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612211