Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Origin of Remote Work

2.2. Concept of Remote Work

2.3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Remote Work

2.4. Factors That Affect Remote Work

2.5. Origins of Work Stress

2.6. Concept of Work Stress

2.7. Causes of Work Stress

2.8. Effects of Work Stress

2.9. Strategies to Prevent Work Stress

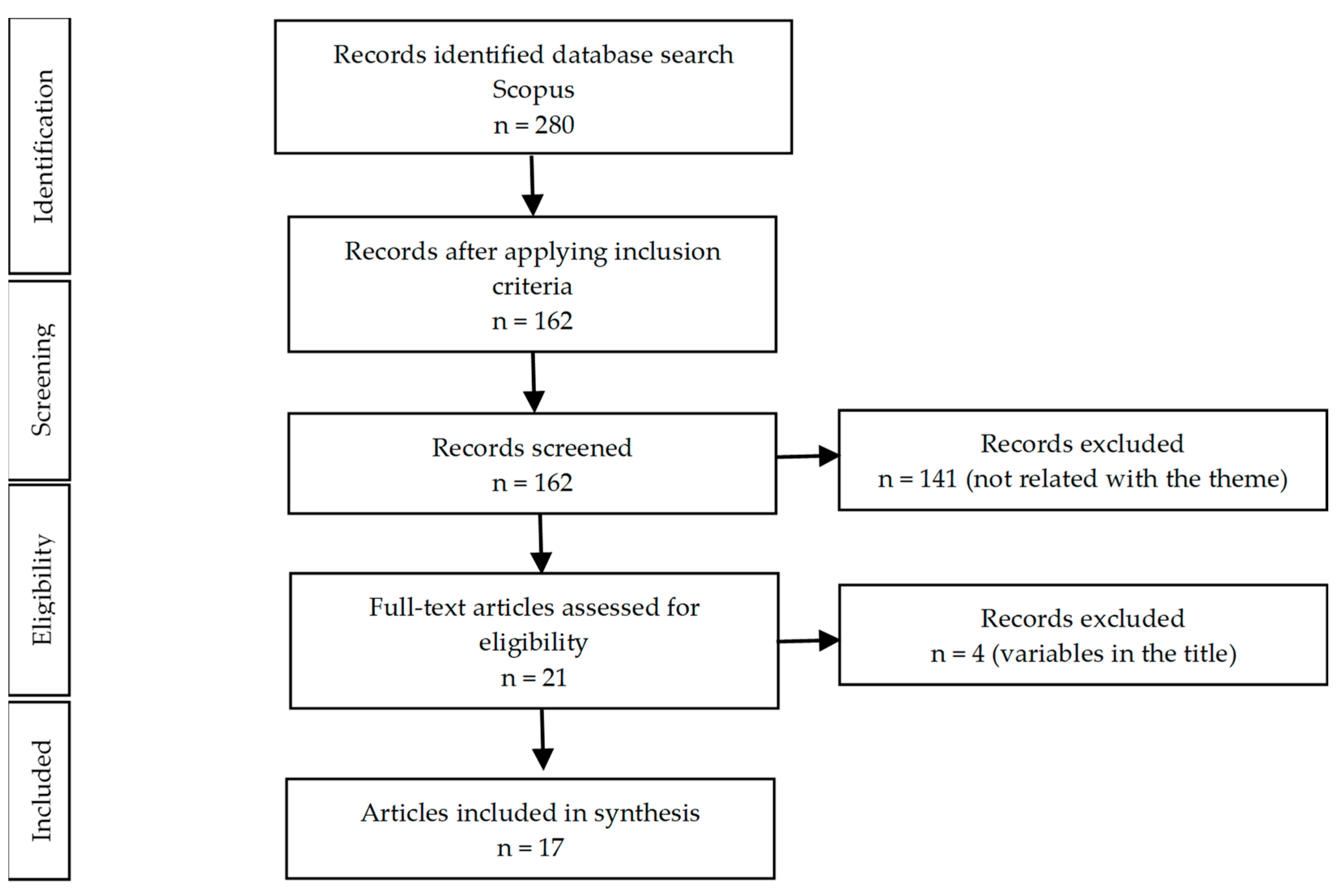

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Procedure

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

3.3. Research Selection

3.4. Analysis of the Quality of the Selected Articles

4. Results

4.1. Existing Scientific Information about the Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.2. Remote Work Factors That Influence the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.3. Findings of the Study on the Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Characterizes COVID-19 as a Pandemic-PAHO/WHO|Pan American Health Organization. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/11-3-2020-oms-caracteriza-covid-19-como-pandemia (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R. Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic in Daily Life. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2020, 10, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, A.; Adegboye, O.A.; Adekunle, A.I.; Rahman, K.M.; McBryde, E.S.; Eisen, D.P. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Global Call to Action for a People-Centred Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis That Is Inclusive, Sustainable and Resilient. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/109/reports/texts-adopted/WCMS_806097/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- OIT. Las Normas de la OIT y la COVID-19 (Coronavirus)—Versión 3.0. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/standards/WCMS_781446/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- CEPAL-OIT. Coyuntura Laboral en América Latina y el Caribe: El Trabajo en Tiempos de Pandemia: Desafíos Frente a la Enfermedad por Coronavirus (COVID-19); CEPAL: Vitacura, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound y OIT. Trabajar en Cualquier Momento y en Cualquier Lugar: Consecuencias en el Ámbito Laboral. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/santiago/WCMS_723962/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Satpathy, S.; Patel, G.; Kumar, K. Identifying and Ranking Techno-Stressors among IT Employees Due to Work from Home Arrangement during COVID-19 Pandemic. Decision 2021, 48, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, A.; Yokoi, K.; Ishibashi, Y.; Akatsuka, Y.; Inoue, T. Remote Work Decreases Psychological and Physical Stress Responses, but Full-Remote Work Increases Presenteeism. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 730969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergine, I.; Gatti, F.; Berta, G.; Marcucci, G.; Seccamani, A.; Galimberti, C. Teachers’ Stress Experiences during COVID-19-Related Emergency Remote Teaching: Results from an Exploratory Study. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 1009974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveh, I.; Morad, S.; Shacham, M. Sense of Competence and Feelings of Stress of Higher Education Faculty in the Transition to Remote Teaching: What Can We Learn from COVID-19 Pandemic in the Long Run. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madero Gómez, S.; Ortiz Mendoza, O.E.; Ramírez, J.; Olivas-Luján, M.R. Stress and Myths Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Remote Work. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2020, 18, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamini, M.; Massi, M.F. Avances y desafíos laborales frente a la nueva ley de teletrabajo: Un análisis a partir de los discursos de actores políticos, empresariales y gremiales. Opin. Juríd. 2022, 21, 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- MacRae, I.; Sawatzky, R. Remote Working: Personality and Performance Research Results; Thomas International: Marlow, UK, 2020; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, D. Teletrabajo: Breve Historia en 6 Claves de Algo Más Que Una Moda y Algo Menos Que Una Revolución Laboral. Business Insider España. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.es/historia-teletrabajo-claves-ultima-revolucion-laboral-global-1051091 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Niles, J.M.; Carlson, F.R.; Gray, P.; Hanneman, G.G. The Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff; John Willey: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1976; Volume 88. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Teleworking during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Practical Guide. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/WCMS_758007/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Sullivan, C. What’s in a Name? Definitions and Conceptualisations of Teleworking and Homeworking. New Technol. Work Employ. 2003, 18, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buira, J. El Teletrabajo. Entre el Mito y la Realidad; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, J.S.F.; Palamidas, D.; Marshall, S.; Loomes, W.; Snook, S.; Leon, R. Teleworking from Home Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Public Health Workers (TelEx COVID-19 Study). BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides, K.M.; Aguilar, G.P.; Benavides, Y.M. El Teletrabajo, valoraciones de las personas trabajadoras en relación con las ventajas y desventajas, percepción de estrés y calidad de vida. Rev. Nuevo Humanismo 2021, 9, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Kłopotek, M. The advantages and disadvantages of remote working from the perspective of young employees. Organ. Manag. 2017, 4, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Mullins, R. Teletrabajo: Ventajas y Desventajas en las Organizaciones y Colaboradores. Rev. FAECO Sapiens 2021, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.; Pereira, R.; Bianchi, I.S.; da Silva, M.M. Decision Factors for Remote Work Adoption: Advantages, Disadvantages, Driving Forces and Challenges. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberga, S.; Pylinskaya, T.P. Remote Work—Advantages and Disadvantages on the Example in It Organisation. In Proceedings of the NORDSCI International Conference, Athens, Greece, 19–23 August 2019; pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez Camacho, C.M. Teletrabajo: Una Revisión Teórica Sobre sus Ventajas y Desventajas. Bachelorthesis, Universidad de Especialidades Espíritu Santo. 2017. Available online: http://repositorio.uees.edu.ec/handle/123456789/2353 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Ruiz, I.A.; Hierro, F.J.H.; Trigueros, C.S. El Trabajo a Distancia: Una Perspectiva Global; Aranzadi/Civitas: Pamplona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Nicholson, N. Home, Sweet Work: Requirements for Effective Home Working. J. Gen. Manag. 1997, 23, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, S.; Garud, R.; Wiesenfeld, B.; Gupta, V. Factors Contributing to Virtual Work Adjustment. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, W.; Sivunen, A.; Blomqvist, K.; Olsson, T.; Ropponen, A.; Henttonen, K.; Vartiainen, M. Factors Influencing Adjustment to Remote Work: Employees’ Initial Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquel Cajas, A.F.; Cajas Bravo, V.T.; Dávila Morán, R.C. Remote Work in Peru during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, V.; Alarcón, V.; Hernandez, J.; Kaplan, D.; Novella, R.; Chaves, M.N. El Futuro del Trabajo en América Latina y el Caribe: La Flexibilidad, ¿Llegó para Quedarse? Publications BID. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/viewer/El-futuro-del-trabajo-en-America-Latina-y-el-Caribe-la-flexibilidad-llego-para-quedarse.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Faya Salas, A.; Venturo Orbegoso, C.; Herrera Salazar, M.; Hernández Vásquez, R.M. Autonomía del trabajo y satisfacción laboral en trabajadores de una universidad peruana. Apunt. Univ. Rev. Investig. 2018, 8, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound; EU-OSHA. Psychosocial Risks in Europe: Prevalence and Strategies for Prevention|Safety and Health at Work EU-OSHA. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/psychosocial-risks-europe-prevalence-and-strategies-prevention (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Pinto, A.; Muñoz, G.J. Teletrabajo: Productividad y bienestar en tiempos de crisis. Esc. Psicol. 2020, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, L.C.; Menges, J.I. Remote Work Mindsets Predict Emotions and Productivity in Home Office: A Longitudinal Study of Knowledge Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 37, 481–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Valencia, Y.L. Riesgos psicosociales y teletrabajo. Cat. Editor. 2021, 1, 202–227. [Google Scholar]

- Selye, H. Chapter 1. What Is Stress? Metabolism 1956, 5, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- French, J.R.P.; Kahn, R.L. A Programmatic Approach to Studying the Industrial Environment and Mental Health. J. Soc. Issues 1962, 18, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Hernández, P.; Salanova Soria, M.; Peiró Silla, J.M. El estrés laboral: ¿Un concepto cajón-de-sastre? Proy. Soc. Rev. Relac. Labor. 2003, 10–11, 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Peiro Silla, J.M. El Estrés Laboral: Una Perspectiva Individual y Colectiva. Investig. Adm. 2001, 18, 30. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Stress at Work: A Collective Challenge. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/resources-library/publications/WCMS_466549/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.; Griffiths, A.; Rial-Gonzalez, E. Work-Related Stress; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. Causes and Management of Stress at Work. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilla-Gutierrez, T. Los Riesgos Psicosociales. DYNA-Ing. Ind. 2010, 85, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAHO; WHO. PAHO/WHO|Work Stress Is a Burden for Individuals, Workers and Societies. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Available online: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11973:workplace-stress-takes-a-toll-on-individuals-employers-and-societies&Itemid=0&lang=es#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- WHO; ILO. Mental Health at Work; Report; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/areasofwork/workplace-health-promotion-and-well-being/WCMS_856976/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Azzi, M. El Estrés, los Accidentes y las Enfermedades Laborales Matan a 7500 Personas Cada Día|Noticias ONU. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2019/04/1454601 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Atalaya, M. El Estrés Laboral y su influencia en el trabajo. Ind. Data 2001, 4, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M. Fatigue: The Most Critical Accident Risk in Oil and Gas Construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawanto, D.W.; Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Economies 2021, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, F.G. El Proyecto de Investigacion. Introduccion a La Metodologia Cientifica, 6th ed.; Episteme: Caracas, Venezuela, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, E. Metodología de la Investigación Científica, 1st ed.; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos: Lima, Peru, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Villasís-Keever, M.Á.; Rendón-Macías, M.E.; García, H.; Miranda-Novales, M.G.; Escamilla-Núñez, A.; Villasís-Keever, M.Á.; Rendón-Macías, M.E.; García, H.; Miranda-Novales, M.G.; Escamilla-Núñez, A. La revisión sistemática y el metaanálisis como herramientas de apoyo para la clínica y la investigación. Rev. Alerg. México 2020, 67, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Eguía, R. ¿Revisión Sistemática, Revisión Narrativa o Metaanálisis? Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor 2014, 21, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rother, E.T. Revisión sistemática X revisión narrativa. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2007, 20, v–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Thomas, J.; Higgins, J.; Deeks, J.; Clarke, M. Chapter I: Introduction. In Manual Cochrane para Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones Versión 6.3; Cochrane: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-i (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; for the PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Catalá-López, F.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C. How to Properly Use the PRISMA Statement. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciapponi, A. La declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para reportar revisiones sistemáticas. Evid. Actual. Práct. Ambulatoria 2021, 24, e002139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Thomas, J.; Oliver, S. Clarifying Differences between Review Designs and Methods. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhen, V.; Cartwright, T. Feasibility and Outcome of an Online Streamed Yoga Intervention on Stress and Wellbeing of People Working from Home during COVID-19. Work 2021, 69, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wontorczyk, A.; Rożnowski, B. Remote, Hybrid, and On-Site Work during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic and the Consequences for Stress and Work Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradoto, H.; Haryono, S.; Wahyuningsih, S.H. The Role of Work Stress, Organizational Climate, and Improving Employee Performance in the Implementation of Work from Home. Work 2022, 71, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from Home during the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Impact on Employees’ Remote Work Productivity, Engagement and Stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, F.; Zappalà, S. Social Isolation and Stress as Predictors of Productivity Perception and Remote Work Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Concern about the Virus in a Moderated Double Mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Bala, H.; Dey, B.L.; Filieri, R. Enforced Remote Working: The Impact of Digital Platform-Induced Stress and Remote Working Experience on Technology Exhaustion and Subjective Wellbeing. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 151, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Reyes, J.; Idrovo-Carlier, S.; Duque-Oliva, E.J. Remote Work, Work Stress, and Work–Life during Pandemic Times: A Latin America Situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, E.; Sağaltıcı, E.; Geniş, B.; Günday Toker, Ö. Predictors of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Remote Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Work 2021, 70, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Workload, Techno Overload, and Behavioral Stress during COVID-19 Emergency: The Role of Job Crafting in Remote Workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dela Cruz, L.A. Machine Learning—Based Risk Assessment on Stress of IT Employees Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2022, 12, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marawan, H.; Soliman, S.S.; Allam, H.K.; Raouf, S.Y.A. Effects of Remote Virtual Work Environment during COVID-19 Pandemic on Technostress among Menoufia University Staff, Egypt: A Cross-Sectional Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 53746–53753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratowicz, B.; Godlewska-Werner, D.; Połomski, P.; Khosla, M. Satisfaction with Job and Life and Remote Workin the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Perceivedstress, Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2022, 10, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudzicka-Czupała, A.; Żywiołek-Szeja, M.; Paliga, M.; Grabowski, D.; Krauze, N. Remote and On-Site Work Stress Severity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison and Selected Conditions. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2023, 36, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacolino, C.; Cervellione, B.; Isgrò, R.; Lombardo, E.M.C.; Ferracane, G.; Barattucci, M.; Ramaci, T. The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Metacognition in Teachers’ Stress during Pandemic Remote Working: A Moderated Mediation Model. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natomi, K.; Kato, H.; Matsushita, D. Work-Related Stress of Work from Home with Housemates Based on Residential Types. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tump, D.; Narayan, N.; Verbiest, V.; Hermsen, S.; Goris, A.; Chiu, C.-D.; Van Stiphout, R. Stressors and Destressors in Working From Home Based on Context and Physiology from Self-Reports and Smartwatch Measurements: International Observational Study Trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e38562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.W.; Priestley, J.L.; Moore, B.A.; Ray, H.E. Perceived Stress, Work-Related Burnout, and Working from Home Before and during COVID-19: An Examination of Workers in the United States. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211058193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Workers | Employers and Organization | Workers | Employers and Organization |

| Virtual promotion | Increased productivity of workers | Inadequate workspaces | Limited communication between workers within the organization |

| Balance between private and work life | Reduction in expenses in facilities (electricity, water, telephone, internet, etc.) | Lack of communication Invisibility in the organization | Unclear processes |

| Flexible schedules | Improvements in personnel selection | Overtime work | Lack of compensation and benefits |

| Reduction in transfer costs | Retention of trained personnel | Expenses previously assumed by employer | Lack of work coordination |

| Reduction in clothing costs to work | Decentralized processes | Conflicts between work and personal life | Lack of commitment from workers |

| Increased productivity | Improvements to organizational culture | Career development | Organizational culture changes |

| Time saving | Commitment to the organization | Limitation of promotions | Job performance measurement |

| Autonomy | Decrease in absenteeism and turnover | Isolation Unrealistic expectations for performance | Lack of effective management and leadership of workers |

| Work satisfaction | Psychological impacts (stress, anxiety, depression, etc.) | Worse organizational information security | |

| Saving and improvement of food | Lack of technical support | ||

| Dimensions | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Flexibility | Support of the organization, execution of activities, adaptation, communication, achievement of goals, and time taken in the achievement of goals |

| Autonomy | Freedom of workload, planning, decision making, necessary inputs, work schedule, and required equipment |

| Productivity | The control and monitoring of activities, achievement of goals, performance evaluation, teamwork, working conditions, job satisfaction, and work overload |

| Technology | Technological infrastructure, communication platforms, ICT, internet connection, digital skills, and resistance to change |

| Psychosocial risks | Stress, discomfort, depression, anxiety, motivation, creativity, social isolation, and interpersonal relationships |

| Approach | Techniques |

|---|---|

| Individual | Time management, physical exercise, relaxation exercises, yoga, social support, biofeedback, behavior modification, free day, and psychological therapy. |

| Organizational | Personnel selection, goal setting, job redesign, group decision making, organizational communication, wellness program, emotional climate control, promoting social support at work, specific treatments for stress, and establishing the social responsibility of organizations. |

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Actuality | All the selected articles that made up the sample are current studies referring to remote work and its influence on work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Exhaustiveness | The studies chosen are the most relevant in the study area. Additionally, they used valid and reliable instruments. |

| Amplitude | From a total of 280 studies found in the database, a sufficient number were considered in the review. In addition, each study verified the use of a representative sample |

| Assessment of risk of bias (rigor) | The findings of each study were reviewed and analyzed in a general way; were based on the evidence that could be inferred; and lacked biases that could call into question the credibility of the review. In this sense, the studies had a cross-sectional and longitudinal design. Statistical methods were adequately applied. |

| Structuring | The review was carried out in an orderly and systematic manner, and followed the methodology. |

| Pertinence | The approaches analyzed from the selected studies were adequate in terms of deepening the subject. |

| Clarity | The narrative of the review was adequate from a grammatical and syntactic point of view; it was also fluid and understandable. On the other hand, the selected studies possessed clarity in way of addressing the subject. |

| Precision | The terms used were adjusted to the lexicon related to the study area and to the aspects that were described above. |

| (Authors, Year, Citation Number) | Title | Source Title | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Wadhen and Cartwright, 2021, [66]) | Feasibility and outcome of an online streamed yoga intervention on stress and wellbeing of people working from home during COVID-19 | Work | Mixed |

| (Wontorczyk and Roznowski, 2022, [67]) | Remote, Hybrid, and On-Site Work during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic and the Consequences for Stress and Work Engagement | International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health | Quantitative |

| (Pradoto et al., 2021, [68]) | The role of work stress, organizational climate, and improving employee performance in the implementation of work from home | Work | Quantitative |

| (Galanti et al., 2021, [69]) | Work From Home During the COVID-19 Outbreak | JOEM | Quantitative |

| (Toscano and Zappalà., 2020, [70]) | Social Isolation and Stress as Predictors of Productivity Perception and Remote Work Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic: the Role of Concern about the Virus in a Moderated Double Mediation | Sustainability | Quantitative |

| (Singh et al., 2022, [71]) | Enforced remote working: The impact of digital platform-induced stress and remote working experience on technology exhaustion and subjective well-being | Journal of Business Research | Quantitative |

| (Sandoval et al., 2021, [72]) | Remote Work, Work Stress, and Work–Life during Pandemic Times: A Latin America Situation | International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health | Quantitative |

| (Şentürk et al., 2021, [73]) | Predictors of depression, anxiety and stress among remote workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Work | Quantitative |

| (Ingusci et al., 2021, [74]) | Workload, Techno Overload, and Behavioral Stress During COVID-19 Emergency: The Role of Job Crafting in Remote Workers | Frontiers in Psychology | Quantitative |

| (Dela Cruz, 2022, [75]) | Machine Learning—Based Risk Assessment on Stress of IT Employees Working from Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines | International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering | Quantitative |

| (Marawan et al., 2021, [76]) | Effects of remote virtual work environment during COVID-19 pandemic on technostress among Menoufia University Staff, Egypt: a cross-sectional study | Environmental Science and Pollution Research | Quantitative |

| (Kondratowicz et al., 2022, [77]) | Satisfaction with job and life and remote working the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem | Current issues in personality psychology | Quantitative |

| (Chudzicka et al., 2023, [78]) | Remote and on-site work stress severity during the COVID-19 pandemic: comparison and selected conditions | International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health | Quantitative |

| (Iacolino et al., 2022, [79]) | The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Metacognition inTeachers’ Stress during Pandemic Remote Working: A Moderated Mediation Model | European Journal of Investigation Health, Psychology and Education | Quantitative |

| (Natomi et al., 2022, [80]) | Work-Related Stress of Work from Home with Housemates Based on Residential Types | International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health | Quantitative |

| (Tump et al., 2022, [81]) | Stressors and Destressors in Working From Home Based on Context and Physiology From Self-Reports and Smartwatch Measurements: International Observational Study Trial | Jmir Formative Research | Quantitative |

| (Hayes et al., 2021, [82]) | Perceived Stress, Work-Related Burnout, and Working From Home Before and During COVID-19: An Examination of Workers in the United States | SAGE Open | Quantitative |

| (Authors, Year, Citation Number) | Remote Work Factors That Influence Work Stress | Main Factors |

|---|---|---|

| (Wadhen and Cartwright, 2021, [66]) | This study focused on exploring the potential of online, streamed yoga to help reduce stress for remote workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yoga implementation transmitted online minimizes stress, anxiety, depression, and improves self -efficacy and mental well-being. | Mental well-being and physical well-being. |

| (Wontorczyk and Roznowski, 2022, [67]) | This study focuses on analyzing remote work and hybrid work, as well as its influence on the stress and labor commitment of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional loads were associated with workers such as isolation, the blur of borders between work and home, as well as domestic conflicts. In addition, the insufficiency of the team, organization, and ergonomics were also considered. | Work commitment, isolation, lack of work–home balance, absence of team and organization, demands, control, support management, support from colleagues, and relationships. |

| (Pradoto et al., 2021, [68]) | This study was based on the effect of work stress and organizational climate on the behavior of remote workers of small and medium enterprises during the pandemic. In this sense, the organizational climate was the cause of labor inconveniences, especially in terms of work stress, which manifested as low satisfaction, performance, the rotation of personnel, absenteeism, and abandonment of work. | Inadequate organizational climate and worker performance. |

| (Galanti et al., 2021, [69]) | This research concentrated on the impact of the pandemic in conflicts between family and work, social isolation, environmental distractions, labor autonomy, self-leadership, productivity, labor commitment, and stress in remote workers. | Lack of balance between family and work, social isolation, distractions, work autonomy, self-leadership, productivity, and work commitment. |

| (Toscano and Zappalà., 2020, [70]) | This research involved the analysis of social isolation and its impact on the stress, productivity, and personal satisfaction of the workers within the framework of the implementation of remote work. | Social isolation, productivity, personal satisfaction, and concern for health. |

| (Singh et al., 2022, [71]) | This study concentrated on analyzing the forced remote work during the pandemic, the impact of stress induced by digital platforms, as well as exhaustion and subjective well-being. The process of adapting to digital platforms stood out since excessive technology use can cause techno-stress. | Impact of digital platforms, exhaustion, intensity, resilience, and subjective well-being. |

| (Sandoval et al., 2021, [72]) | This study focuses on people who were able to switch from traditional work to remote work during the pandemic in certain Latin American countries. Remote work lead to increased perceived stress, decreased work–life balance, increased productivity, and engagement. | Work–life imbalance, productivity, and commitment. |

| (Şentürk et al., 2021, [73]) | This study stands out for addressing the predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress in workers who participated in working remotely for the first time in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Various factors determined the appearance of stress, such as poor sleep quality, concentration problems, and low levels of control over work time, as well as low levels of physical activity, increased workload, and financial situations. | Time spent on housework, time spent caring for children, daily work hours, workload, distractions, and financial situation. |

| (Ingusci et al., 2021, [74]) | This research focuses on exploring the effect of work overload on behavioral stress in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Remote workers faced different difficulties such as those related to workspaces, equipment and internet connection, among others. The workers also expressed the difficulty in establishing limits between work and personal life. | Workload, technological overload, and work preparation. |

| (Dela Cruz, 2022, [75]) | This study involved evaluating the level of stress in the home workers of a computer consulting company. The advantages and disadvantages of working from home and the effect on well-being were discussed, and the classification of employees, their needs, and concerns were highlighted. | Human interaction, office benefits, saving time and money, personal time, and habits. |

| (Marawan et al., 2021, [76]) | This research was based on the study of techno-stress during the COVID-19 pandemic, which became more common as a result of the measures that were implemented to restrict the spread of the virus. In this regard, techno-stress and the challenges of the virtual remote work environment among members of the Menoufia University located in Egypt were analyzed. | Age, gender, fear of unemployment, economic hardship, health concern, type of residence, type of job, Wi-Fi performance, computer status, and cortisol level. |

| (Kondratowicz et al., 2022, [77]) | This research was based on the evaluation of the relationship between remote work during the pandemic and the degree of job and personal satisfaction, as well as the perception of stress, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. | Job satisfaction, personal satisfaction, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. |

| (Chudzicka et al., 2023, [78]) | This study was developed with the objective of analyzing the severity of work stress in remote workers and on-site workers during the pandemic. | Work–family conflict, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, affective commitment, regulatory commitment, and commitment to continuity. |

| (Iacolino et al., 2022, [79]) | This study involved an investigation on the adaptation to social, labor changes, and the technological methods for distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers were subjected to greater work pressures, which affected their well-being, as well as increased their stress and exhaustion. In this sense, the dysfunctional changes in adaptation to the new forms of teaching that were mediated by technological tools could be reduced through protective factors of emotional intelligence and metacognition. | Emotional intelligence, metacognition, burnout, remote-teaching risk factors, unfamiliarity with technology platforms, a lack of a dedicated location for remote teaching, a need to adjust to Internet use and teaching methods, difficulties in class management, and difficulties in coordinating with colleagues. |

| (Natomi et al., 2022, [80]) | This study analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work environments, specifically the influence of remote work on worker stress. The relationship between work stress and the remote work environment was analyzed through various factors such as the type and size of the house, housemates, workspace, and environmental improvements. | Gender, age, housemates, environmental conditions, physical activity, job and personal satisfaction, outside noise, family group interference in the work environment, and mental stress from web meetings. |

| (Tump et al., 2022, [81]) | This study covered the analysis of remote work that was developed through the use of technology (smart watches, smart phones, etc.) to establish stressful and de-stressing factors during the pandemic. | Age, gender, workspace, burnout experienced in the past, family events that clash with work, support from colleagues, work intensity, pandemic anxiety, use of smart watches as a work tool, and environmental conditions such as air and light. |

| (Hayes et al., 2021, [82]) | This study was developed with the purpose of analyzing the impact of involuntary remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic on perceived stress and job burnout in workers with and without experience in this type of work. | Age, gender, remote work experience, number of hours worked per week, time at current job, education, and burnout. |

| Condition | Negative Effects of Remote Work That Can Generate Stress | Positive Effects of Remote Work |

|---|---|---|

| Mental well-being, physical well-being, financial situation, age, gender, unemployment, type of residence, type of job, Internet access, computer status, cortisol level, self-efficacy, self-esteem, emotional intelligence, physical conditions of the workplace, and remote work experience. | Social isolation, changes in work–home balance, increased job demands, increased control, lack of supportive management, lack of peer support, inadequate organizational climate, decreased performance, distractions, decreased productivity, lack of commitment labor, impact of digital platforms, technological exhaustion, and burnout. | Increase in performance, improvement in work commitment, improvement in work autonomy, greater self-leadership, increase in productivity, improvement in work commitment, personal satisfaction, resilience, and saving time and money. |

| (Authors, Year, Citation Number) | Sample | Results | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Wadhen and Cartwright, 2021, [66]) | A six-week pilot study was developed with a sample of n = 34, of which 17 were part of the control group and 17 of the experimental group. | The control group obtained an average of 9.59 and the experimental group 10.18 in the pre-test. Meanwhile, in the post-test, they obtained 8.06 and 6.47, respectively. | Significant improvements were found in the control group for perceived stress, mental well-being, depression, and self-efficacy, but not for stress and anxiety. The benefits they experienced in physical and mental health were verified, as well as the acceptance and enjoyment of participation. |

| (Wontorczyk and Roznowski, 2022, [67]) | This study was cross-sectional, and the sample was 544 workers: remote (n = 144), hybrid (n = 142), and in person (n = 258). | Part of the findings reflected that 46.7% responded that they do not respond to matters not related to work outside of working hours. | No significant differences were found between the groups regarding the intensity of work engagement, whether remote or hybrid. People who worked remotely perceived the most positive, negative, and temporary aspects of remote work. The temporary aspect of remote work was also felt by employees performing their professional functions in a hybrid way. |

| (Pradoto et al., 2021, [68]) | The sample was 95 remote workers from small- and medium-sized companies. | The organizational climate had a significant impact on work stress with p = 0.023 < 0.05. Job stress had a significant influence on the performance of workers with p = 0.004 < 0.05. The organizational climate had a direct effect on the performance of workers with p = 0.000 < 0.05. | The organizational climate had a significant impact. Job stress had a significant influence on the performance of workers. The organizational climate had a direct effect on the performance of workers. |

| (Galanti et al., 2021, [69]) | The sample was 209 remote workers. | Conflict between family and work, as well as social isolation as part of remote work during the pandemic were negatively associated. | On the other hand, self-leadership and self-esteem were positively related to productivity and work commitment. Similarly, family–work conflict and social isolation were negatively associated with the stress caused by remote work, which was not impacted by autonomy and self-leadership. |

| (Toscano and Zappalà., 2020, [70]) | The sample was 265 remote workers. | It was found that social isolation was significantly related to stress since β = 0.59; p < 0.01. | Social isolation played a fundamental role in the generation of stress in the remote workers, which lead to a decrease in productivity, and this was related to job satisfaction. Concern about the virus decreased the relationships between social isolation and job satisfaction, on the one hand, due to the perceived productivity of remote work and, on the other hand, job satisfaction. Concern about the virus moderated the relationships between social isolation and job satisfaction. |

| (Singh et al., 2022, [71]) | The sample was 306 workers. | A total of 83.0% of participants worked remotely (at least 1% of their work), and 57.2% worked remotely completely. | The digital platforms used in the work and personal context induced techno-stress during the mandatory remote work period, which increased psychological tensions, generated technological exhaustion, and decreased subjective well-being. Employees with experience working remotely could better handle techno-stress. Employees with high resilience suffered decreased well-being in the presence of induced techno-stress and technology burnout. |

| (Sandoval et al., 2021, [72]) | The sample was 1285 participants. | Remote work increased perceived stress (β = 0.269; p < 0.01), reduced work–life balance (β = 0.225; p < 0.01) and job satisfaction (β = 0.190; p < 0.01), as well as productivity (β = 0.120; p < 0.01) and commitment (β = 0.120; p < 0.01). | Perceived stress had a mediating consequence that minimized the positive effect of working remotely on productivity and engagement. On the contrary, perceived stress exerted a mediating function between the remote work that benefits the negative influence of demands and the perception of the balance between work and personal life. On the other hand, the gender study indicated that perceived stress affected the productivity of men more acutely than in women. |

| (Şentürk et al., 2021, [73]) | The sample was 459 participants. | The levels of depression, anxiety, and stress were 17.9%, 19.6%, and 19.6%, respectively. | Predictors of stress in remote workers were poor sleep quality, difficulty concentrating at work, worrying about financial situation, and loneliness in the workplace. In the case of depression, the predictors were poor sleep quality, difficulties concentrating at work, loneliness, lack of control over work hours, and lack of physical activity. Regarding the predictors of anxiety, the influence of poor sleep quality and increased workload was verified. On the other hand, the existence of greater stress, anxiety, and depression was found in women. |

| (Ingusci et al., 2021, [74]) | This study involved 530 remote workers. | This study reflected acceptable results in work overload, and this was measured by the latent variables of workload (λWORKLOAD = 0.62, p < 0.000) and technological overload (λTECHNO OVERLOAD = 0.70, p < 0.000). | The measurement of job crafting was partial; specifically, the direct consequence between work overload and behavioral stress was positive. In addition, the negative effect through the mediation of job crafting was significant. Therefore, the findings reflected that job crafting can play a fundamental role as a protective element in terms of managing the negative effects of work overload, especially in the context of intense remote work and the use of technologies. |

| (Dela Cruz, 2022, [75]) | The sample consisted of 103 technology employees. | The results indicated that 63.1% believed that domestic problems and the lack of interaction were disadvantages of remote work. Likewise, 83.3% indicated that the lack of human interaction affected the health of workers, causing them stress. | Single employees were the ones who experienced the most stress. The biggest disadvantage of working from home was that homes are not suitable for working. There were problems due to the slowness of the internet and the increase in public service expenses. The advantages of working from home were related to the elimination of travel hours, regardless of the marital status and position of the worker. |

| (Marawan et al., 2021, [76]) | This study involved 142 workers. | The findings revealed that work overload was significantly related to female gender and a poor Wi-Fi work environment (p value < 0.001 and 0.002, respectively). | The participants were mostly resident teachers from rural areas who had access to Wi-Fi in an inadequate work environment, had a lack of technical training, and had significantly higher levels of techno-stress subscales. Most of the techno-stress subscales had a significant correlation with age and blood cortisol levels. The predictors of work overload in the multivariate regression were female gender and a work environment with poor Wi-Fi. High levels of techno-stress were significantly influenced by age, teacher level, and the female gender. |

| (Kondratowicz et al., 2022, [77]) | This study was carried out with the participation of 283 workers. | The results indicated that there was a relationship between remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic and job and personal satisfaction. In addition, the levels of perceived stress, self-efficacy, and self-esteem played a mediating role in this relationship. | Remote work was related to personal and job satisfaction, and this relationship was mediated by the degree of stress, self-efficacy, and self-esteem experienced. |

| (Chudzicka et al., 2023, [78]) | This study involved 946 workers from the education system and the BSS sector in different Polish organizations. | A total of 39% of the participants believed that work stress had a greater impact in the face-to-face modality, while 35% affirmed that it was in the remote modality. | Conflict between remote work and family, as well as job satisfaction, were the predictors of work stress in the remote and face-to-face contexts. In summary, remote work was related to less serious work stress than in the case of face-to-face work. In both forms of work, the greater the degree of work–family conflict, the greater the severity of the stress, but the greater the job satisfaction, the less the severity of stress. |

| (Iacolino et al., 2022, [79]) | A total of 604 teachers participated in the study. | The findings reflected that stress was a dependent variable (R2 = 0.23, F (3, 600) = 89.42, p < 0.001), while the direct impact of remote work risk factors on stress was slightly significant. | Emotional intelligence was a mediator in the relationship between various risk factors of remote work, as well as stress and burnout. Metacognition was a significant mediating factor in the relationship between risk factors and emotional intelligence. The importance of the emotional and metacognitive skills of teachers in promoting quality of life and psychological well-being was highlighted. |

| (Natomi et al., 2022, [80]) | The study sample consisted of 500 workers. | Work-from-home environments according to the top three types of residences in Japan were studied in relation to high stress levels, which accounted for 17.4% of the participants. | The workers had problems associated with noise regardless of the type of residence. HSWs in single-family homes and apartments had issues with the noise levels generated by their housemates. The workers who lived in these types of residences were relatively older, so they usually had older children who would require a certain level of privacy. Home workers with insufficient privacy could not adapt to these types of environments and suffered from a great deal of stress. |

| (Tump et al., 2022, [81]) | The sample was 202 workers. | The remote-work stressors detected were as follows: daily life limits on work (p = 0.05), work intensity (p = 0.01), burnout history (p = 0.03), anxiety toward the pandemic (p = 0.04), and environmental noise (p = 0.01). | The most significant environmental stressors in remote work were the distractions caused by other people, distractions from daily life, and noise in the environment. The most significant lifestyle-related environmental stressors were access to fresh air and sunlight, and de-stressors were short breaks, social interactions outside of work, and physical activity. No significant relationship was found between low and high stress during work hours and the quality of sleep during the previous night. |

| (Hayes et al., 2021, [82]) | The sample was 256 workers. | Overall perceived stress scores yielded PSS-10 pre-COVID-19 M = 16.82, SD = 6.29, and during COVID-19 it was M = 19.52, SD = 6.08. | The restrictions of the pandemic increased the perceived stress in all the participants; in addition, age and gender had significant effects on the stress and burnout of the workers. Burnout turned out to be more significant for workers who were previously working remotely before the pandemic. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dávila Morán, R.C. Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612489

Dávila Morán RC. Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612489

Chicago/Turabian StyleDávila Morán, Roberto Carlos. 2023. "Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612489

APA StyleDávila Morán, R. C. (2023). Influence of Remote Work on the Work Stress of Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(16), 12489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612489