1. Introduction

The disposal of used or undesired clothing, as a part of the post-purchase phase of consumers’ decision-making processes [

1], has a significant environmental impact [

2,

3,

4]. Short-lived fashion trends and throwaway culture have resulted in discarded clothing becoming a new form of solid waste, thereby negatively affecting the environment and wasting resources [

5,

6]. Although a variety of environmentally friendly clothing disposal channels, such as donating, giving away, reselling, renting, and recycling bins, is available [

7], it is estimated that roughly 75% of textile waste ends up in landfills worldwide and only 25% is reused or recycled [

8,

9]. Several studies have focused on clothing disposal practices [

10], and studies on clothing disposal have primarily focused on adults [

11,

12,

13]. However, only a limited number of studies has been conducted on the behavior concerning the disposal of children’s clothing.

Children’s clothing has a shorter lifespan with one owner compared to adult clothing, primarily due to rapid physical growth [

14,

15]. Additionally, their engagement in various activities can contribute to wear-and-tear issues, increasing the likelihood of these garments being disposed of. Studies have shown that children’s clothing with damage is more prone to being discarded as trash [

12,

16]. Although unwanted children’s clothing is more often given away than adult clothing [

17], its short lifespan and the culture of throwing away damaged items still contribute to environmental concerns.

In China, efforts to promote the reuse and recycling of discarded clothing include the establishment of disposal channels like recycling boxes in communities and online clothing-recycling platforms (OCRPs) such as Feimayi [

18]. OCRPs provide online booking and offline free pick-up services to promote clothing recycling through reuse and recycling processes [

13]. As a promising clothing-recycling platform, after disinfecting and sorting, OCRPs dispose of clothing through reuse and recycling methods (such as donation, export sales, and industrial material) based on the condition of the collected items. However, despite these initiatives, clothing is still frequently thrown away, and OCRPs, as an emerging disposal channel with potential, have not been widely accepted by consumers [

13]. Understanding consumers’ choice of disposal channels is crucial to promoting sustainable disposal behavior [

19]. Taking into consideration their popularity among consumers and the chronological order of their appearance, we categorize the disposal channels of recycling boxes, giving away, and throwing away as conventional disposal channels while referring to OCRPs as an emerging disposal channel in this study.

This research aims to identify factors influencing consumers’ choice of disposal channels regarding children’s clothing in China. The specific research questions addressed in this study are as follows:

- (RQ 1)

What are the factors that influence the consumers’ choice of conventional disposal channels for children’s clothing?

- (RQ 2)

What is the usage status of online clothing-recycling platforms among consumers, and what are the barriers and facilitators for consumers to using them?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides the literature review, followed by the research method, which combines quantitative and qualitative approaches, in

Section 3.

Section 4 presents the quantitative and qualitative results related to factors influencing consumers’ choice of conventional disposal channels and the usage status of OCRPs, along with barriers and facilitators for their adoption. In

Section 5, we discuss the exploration based on the combined quantitative and qualitative findings.

Section 6 presents the conclusions and implications drawn from the study, whereas

Section 7 outlines the limitations and suggests areas for further research.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

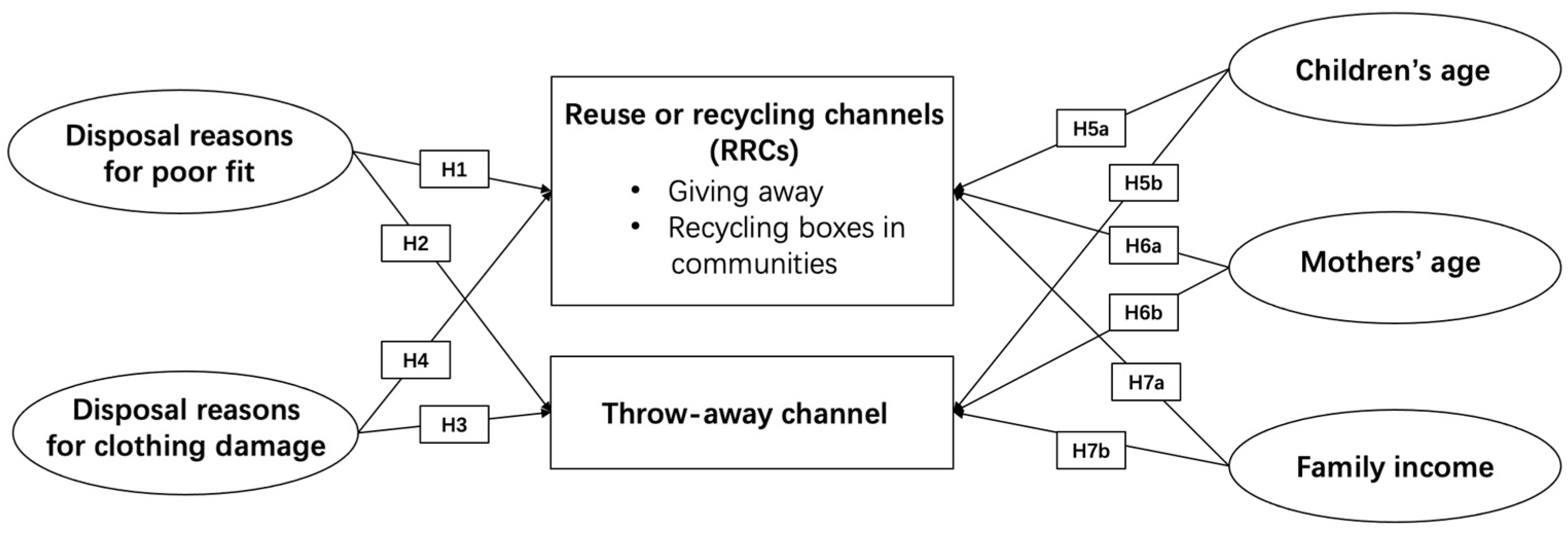

This study delves into two research streams. Firstly, we construct a framework illustrating the factors that influence consumers’ choice of conventional disposal channels for children’s clothing (

Figure 1). Secondly, we investigate the usage status of online clothing-recycling platforms among consumers, along with the barriers and facilitators for their adoption. In this pursuit, we employ the Capability Opportunity Motivation–Behavior model (COM-B) as a guiding framework.

2.1. Clothing Disposal Behavior

Clothing disposal behavior refers to the practice of discarding undesired clothes at their end-of-life stage with the current owner [

7,

10,

20]. Consumers’ decisions on why and how to dispose of unwanted clothing have a direct impact on the clothing’s lifespan, the quantity of waste produced, possibilities for reuse and recycling, and product replacement decisions [

4,

19,

21]. Disposal behavior is complex and influenced by various factors [

22], including personal characteristics, product conditions, and situational events [

7].

Individual characteristics, such as income, social class, gender, and life stage, can influence disposal behavior [

23]. Preference for disposal channels also varies with the category of the product [

24]. Additionally, the condition of the clothing product plays a role in disposal decisions. Clothes in good condition are more likely to be reused or recycled, whereas clothes with severe damage are more likely to be thrown away [

7]. Furthermore, situational events also prompt disposal-related decision-making [

22,

24].

Norum [

17] developed a model that describes the relationship between demographic characteristics, disposal reasons, and disposal channels. Demographic characteristics include income, employment, age, and the presence of children; disposal reasons include size, replacement, storage space, and other factors; and disposal channels focus on throwing away, charity, and secondhand stores. Hence, demographic characteristics and disposal reasons can be considered factors influencing consumers’ behavior when using conventional disposal channels. In addition, the COM-B, the core model for behavior-changing guidance, emphasizes that behavior is part of an interaction between opportunities, capability, and motivation [

25]. Zhang and Hale [

26] identified barriers and facilitators of clothing repair behavior based on categories derived from the Theoretical Domain Framework (TDF) domains linked to COM-B. Thus, COM-B can be used to explore the barriers and facilitators for consumers to use the emerging disposal channels.

2.2. Reasons for Disposal of Clothing

Jacoby’s [

24] categorization of factors that influence disposal decisions and reasons for disposal of clothing are classified into three categories: psychological characteristics of the decision-maker, factors intrinsic to the product, and situational factors extrinsic to the product. The definitions of the categories applied to clothing disposal are as follows: (1) psychological characteristics of the decision-maker, including psychological reasons for disposing clothes such as fashion issues or boredom, or no longer suiting the consumers’ taste or style; (2) factors intrinsic to the product, such as the reasons for clothing condition, including wear and tear, misshaping, or staining issues; and (3) situational factors extrinsic to the product, such as the situational reasons that influence clothing disposal, such as a lack of storage space [

27,

28]. In addition, poor fit, as a common disposal reason, does not specifically belong to one of the above three categories, as it is related to both human physical characteristics and product conditions. Therefore, poor fit was considered an individual category in this study.

Laitala [

10] summarized the reasons for disposal of adult clothing as follows: (1) wear and tear, (2) fashion or boredom, (3) poor fit, and (4) lack of storage space. However, children have a greater need for new clothing due to their physical characteristics of growth [

14,

15]. Additionally, various activities could also cause damage to children’s clothing, such as wearing out and stains occurring. According to previous studies, size issues and damage-related issues associated with product factors are the most common reasons for the disposal of children’s clothing [

29,

30]. Hence, poor fit and damage are regarded as the disposal reasons for children’s clothing in this study.

2.3. Clothing Disposal Channels

Clothing disposal channels generally consist of reusing, recycling, recovering, and binning [

7,

31]. Reusing refers to clothing products with satisfactory conditions being used again after cleaning, sorting, and repairing [

10], and it includes the channels of donation, giving away, resale, swapping, and renting [

6,

20]. Recycling involves converting unwearable clothing into new products [

7]. Recycling boxes are used to recycle clothing materials in addition to donations. Reusing and recycling are considered sustainable disposal channels [

4], as they are sequentially ranked next to the lowest environmental impact step, “prevention of waste occurrence” in the five-step waste hierarchy [

10]. This is especially true for reuse, which facilitates prolonged use of clothing [

11,

32]. Recovery refers to the change of energy from one form to another, such as incineration with energy recovery [

33]. Binning refers to the disposal of clothing without recycling or reusing [

10]. Both recovery and binning are considered disposal methods with high environmental impacts [

32]. According to the literature, the clothing items disposed through recovery and binning are all from the “throw away” channel [

7,

31]; therefore, this study identifies throwing away as one channel covering recovery and binning.

Notably, despite being a promising clothing-recycling platform with the potential to effectively and professionally facilitate proper clothing disposal, OCRPs have not garnered widespread consumer acceptance [

13]. In addition, the demand for clothing donations has decreased over time, and they have increasingly been incorporated into community recycling boxes or OCRPs in China. Therefore, giving away, recycling boxes in communities, and throwing away were selected as the primary conventional disposal channels to investigate the influencing factors, and OCRPs were selected as the potential emerging disposal channel to explore the reasons that induce consumers to use or avoid it, based on Chinese realities, professional knowledge, and published studies [

28,

34].

According to Albinsson and Perera [

35], consumers’ disposal decisions are affected by the condition of clothing products. Consumers prioritized clothes with reuse or recycling potential for various purposes after a subjective assessment of their condition when disposing of clothing [

12]. Clothes that need to be disposed of due to poor fit or reasons concerning psychological characteristics or situational factors are likely to be in good condition and can still be valuable to others [

12]. However, clothes that need to be disposed of for reasons belonging to product factors are likely to be damaged due to issues concerning nature, quality, and maintenance [

28]. Clothing items with slight damage are likely to be donated, and clothing items with severe damage are more likely to be thrown away by consumers [

12]. Furthermore, according to Norum [

17], disposal based on size issues is positively related to charity donation, whereas disposal based on garment replacement, which captures the effect of the physical condition of clothing, is positively related to the throw away disposal channel. However, behavior regarding the disposal of children’s clothing needs to be examined in addition to these findings mainly pertaining to adult clothing. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. Disposal based on poor fit for children’s clothing will lead to reuse or recycling channels (RRCs).

H2. Disposal based on poor fit of children’s clothing will not lead to throw away channels.

H3. Disposal based on damage to children’s clothing will lead to the throw away channels.

H4. Disposal based on damage to children’s clothing will not lead to RRCs.

2.4. Characteristics of Children and Parents

Children’s clothing sizes need to be updated more frequently to ensure a proper fit during their periods of highest growth and development [

14,

15,

36]. As a result, the potential for reusing children’s clothing within each age range is significant [

37,

38]. Cruz-Cárdenas and Arévalo-Chávez [

21] emphasize age as the most influential personal characteristics for predicting clothing disposal behavior, and previous studies have confirmed that the age of owners of clothing items does indeed impact clothing disposal behavior [

13,

39]. Although parents and guardians are responsible for the disposal of children’s clothing [

40], children’s personal characteristics also play a role in their clothing disposal decisions. According to Sego [

16], clothing for younger children is commonly given away, whereas items for older children are usually donated to charity, consistent with Norum’s [

17] findings on different disposal patterns for children’s clothes of varying children’s ages. The growth rate among different age groups also results in distinct clothing utilization rates [

41]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are therefore proposed:

H5a. There is a significant difference between children’s ages in terms of using RRCs.

H5b. There is a significant difference between children’s ages in terms of clothing disposal via the throw away channel.

As mothers are usually responsible for household clothing disposal [

39,

42], their personal characteristics play an important role in the study of children’s clothing disposal. According to Laitala [

10], compared to younger consumers, older consumers are more likely to reuse or recycle undesired clothing, or at least donate it to charitable organizations. Birtwistle and Moore [

5] found that young consumers disposed of clothing less responsibly, such as by throwing it away. Meanwhile, according to previous studies, consumers’ incomes influence their disposal channel-related decisions and their attitudes toward the environment [

39,

43,

44]. According to Joung and Park-Poaps [

6], clothing reuse behavior is predicted by economic concerns. Norum [

17] found that higher-income households donate clothing more frequently. Although these findings pertain to adult clothing, the disposal of children’s clothing is also influenced by family circumstances [

40]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a. There is a significant difference in terms of RRCs depending on the mother’s age.

H6b. There is a significant difference in the choice of throw away clothing disposal channel depending on the mother’s age.

H7a. There is a significant difference in terms of RRCs depending on the level of family income.

H7b. There is a significant difference in terms of the choice of throw away clothing disposal channel depending on the level of family income.

2.5. Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (COM)

The COM-B model suggests that behavior can be influenced by capabilities, opportunities, and motivations [

25]. Capability can be either physical (consumers have physical strength or skill) or psychological (consumers have knowledge or psychological skills) to perform behaviors; opportunity can be either physical (what the environment allows to be facilitated in terms of resources, locations, physical barriers, etc.) or social (including interpersonal influences, social cues, and culture norms); motivation can be either reflective (including self-conscious planning and evaluations) or automatic (consumers’ processes involving needs, desires, impulses, etc.) [

25]. In the context of clothing disposal, reflective motivation is related to individuals’ intentions, goals, or beliefs regarding disposal behavior, whereas automatic motivation pertains to the habitual or emotional aspects of disposal behavior. It is suggested that reuse or recycling disposal behaviors could be promoted by improving capability, opportunity, and motivation [

45]. OCRPs have not been widely accepted by consumers in China [

13], indicating that the behavior of using OCRPs remains challenging. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8. The facilitators and barriers for consumers to use OCRPs can be identified based on capability, opportunity, and motivation (COM).

H9. There is a significant difference among COM factors influencing consumers’ behavior of using or avoiding.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methods with closed-ended and open-ended questions to examine the factors influencing conventional disposal channels and the barriers and facilitators for consumers to use potential emerging disposal channels for children’s clothing.

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

The respondents targeted for this study were mothers raising children aged 4–12 years old, as women are generally responsible for household clothing disposal [

32,

39] and mothers often serve as the primary decision-makers in regard to the disposal of children’s items [

16]. In this study, children within the age range of 4–12 years were chosen, as they represent school-age children and are likely to be influenced by parenting and the home environment [

46]. Data were collected from a convenience sample of mothers residing in urban areas of northern China, including cities like Dalian, Shenyang, and Beijing. The data collection took place through an online survey (Wenjuanxing) conducted in February 2023. Utilizing convenience sampling, a non-probability sampling method allowed for the collection of initial primary data concerning specific issues [

47]. Respondents who were raising two or more children were asked to choose one child who met the age range as the survey object.

Prior to the survey, respondents were informed that their responses would be used for research purposes and that their individual data could be withdrawn upon request. To ensure respondents understood the questionnaire statements, pretests were conducted. At the beginning of the survey, participants were provided with a definition of clothing disposal that covered different explanations of disposal channels, including options for reuse and recycling like giving away, recycling boxes in the community, and OCRPs, and discarding by throwing away. Self-administered questionnaires were used for data collection, and a total of 280 questionnaires were distributed, with 259 deemed valid and retained for analysis. According to Roscoe [

48], sample sizes ranging from more than 30 to less than 500 are generally suitable for most research. Within these limits, when samples are to be divided into sub-categories, a minimum sample size of 30 is required for each category. Therefore, the chosen sample size (N = 259) was appropriate for the study.

3.2. Measurement

The questionnaire consisted of three sections related to behavior regarding the disposal of children’s clothing. In the first section, demographic information was collected, including individual characteristics of both the mothers and their children.

The second section involved constructing dependent variables based on the study model. Questions were asked regarding disposal channels for children’s clothing via giving away, recycling boxes in communities, and throwing away, adapted from Degenstein et al. [

7]. These disposal channels were represented as categorical variables, with responses of “Yes” and “No.” In addition to demographic details, independent variables were constructed, including poor fit and clothing damage, adapted from Degenstein et al. [

7] and Jacoby et al. [

24]. These two disposal reasons were represented as categorical variables with responses of “Yes” and “No.” As the dependent variables were binary, binary logistic regression was used for analysis.

In the third section, to gain further insight into OCRP usage and relevant issues, one open-ended question was asked of the respondents: Why do you use or avoid using OCRPs? Following McGowan et al.’s [

49] recommendation, responses were analyzed using an inductive, then a deductive, thematic analysis approach. By using the COM-B created by Michie et al. [

25], themes were linked to COM components. Finally, based on the identified COM component factors, Chi-square tests were used to identify the differences among factors.

3.3. Data Analysis

The quantitative analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28, Release 28.0.0.0, 64-bit edition (Nomi, Japan). Binary logistic regression and Chi-square tests were performed. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and statistical significance was accepted at p ≤ 0.05. Binary logistic regression models were built to evaluate which predictors contributed most to the models. Frequencies and percentages were calculated and compared using Pearson’s chi-square for count data. The chi-square partitioning method was applied to determine the pairwise comparison of groups.

For qualitative analysis, thematic analysis was chosen to understand the reasons behind people’s usage or avoidance of services or procedures [

50]. Initially, thematic analysis was conducted in this study using an inductive approach following Braun and Clarke’s [

51] method. The responses were in Chinese, the native language of the participants, and were translated into English and fully transcribed. To ensure data reliability, the translations underwent meticulous review and correction by the authors. The open-ended responses were examined word by word, and relevant reasons for using or avoiding OCRPs were summarized into open codes. These codes were then assigned to meaningful text segments, resulting in the generation of a list of specific themes. Subsequently, a deductive approach was employed to link these themes with relevant textual content to one or more of the components of COM-B.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics

The demographic details of the 259 respondents are presented in

Table 1. Of the respondents, 50.2% and 49.8% provided information on boys and girls, respectively. The age ranges of the children were 4–6 (35.9%), 7–9 (32.4%), and 10–12 (31.7%). In terms of age, most respondents were aged 41 years and above (37.8%), 30.9% were 35 years and below, and 31.3% were 36–40 years. In terms of annual family income level, most families had a medium level (40.2%), 25.9% had a low level, and 34.0% had a high level.

4.2. Factors That Influence Consumers’ Choice of Conventional Disposal Channels for Children’s Clothing

Using binary logistic regression, we identified the significant predictors that increase disposal channels of giving away, recycling boxes in communities, and throwing away. As shown in

Table 2, the model for the disposal channel of giving away (Model 1) indicated a good fit (Chi-square value of 39.419 with eight degrees of freedom,

p < 0.001, N = 157), which was confirmed by the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (

p > 0.05). As shown in

Table 3, the model for the disposal channel of throwing away (Model 2) indicated a good fit (Chi-square value of 90.976 with eight degrees of freedom,

p < 0.001, N = 116), which was confirmed by the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (

p > 0.05). However, in the case of the disposal channel of recycling boxes in communities, the model did not demonstrate a good fit (Chi-square value of 8.242 with eight degrees of freedom,

p = 0.410 > 0.05, N = 146), indicating that the construction of this model was not statistically significant and that the subsequent indicator results were not statistically significant.

In terms of the model for the disposal channel of giving away, poor fit was a significant predictor, meaning that having the reason of poor fit increased the probability of disposing of children’s clothing by giving away by 3.4 times (p < 0.01). The mother’s age was also a significant predictor; those over 41 years were 4.3 times (p < 0.001) more likely to give away children’s clothing than those under 35 years, and those between 36 and 40 years were two times (p < 0.05) more likely to give away children’s clothing than those under 35 years. In addition, in regard to families’ annual income, middle-income families were 0.4 times (p < 0.05) more likely than low-income families to give away children’s clothing. None of the predictors were statistically significant in the model of another RRC, recycling boxes in communities; thus, H1, H6a, and H7a are partially supported. However, the clothing damage-related disposal reason and children’s age did not significantly influence the respondents’ choice of the disposal channel of giving away; thus, H3 is supported and H5a is rejected.

In the model for the throwing away disposal channel, the reason concerning clothing damage was the most significant predictor; that is, when the reason for clothing damage was present, the probability of disposing of children’s clothing increased by 4.9 times (p < 0.001). In addition, families’ annual income was also a significant predictor; that is, high-income families were 18 times (p < 0.001) more likely to dispose of children’s clothes by throwing them away than those with low income, and middle-income families were 3.7 times (p < 0.01) more likely than low-income families to throw away children’s clothing. Thus, H4 and H7b are supported. However, the disposal reasons relating to poor fit, children’s age, and mother’s age did not significantly influence the respondents’ choice of disposal channel of throwing away; thus, H2 is supported and H5b and H6b are rejected.

4.3. The Usage Status of OCRPs among Consumers and the Barriers and Facilitators for Their Adoption

In the qualitative results, the reasons that lead mothers to use or avoid OCRPs when disposing of children’s clothing were revealed. One open-ended question was included in the survey: Why do mothers choose to use or avoid using OCRPs? Of the respondents, 11.97% (31) reported using OCRPs, whereas 83.03% (228) chose to avoid using them, showing a significant difference in their preferences.

Table 4 presents 15 themes that emerged for using and avoiding OCRPs, categorized based on COM-B. The frequency of occurrences was also recorded for each theme.

The barriers to consumers using OCRPs were identified as psychological capability, physical opportunity, social opportunity, and reflective motivation. These factors hindered their willingness or ability to utilize OCRPs as a disposal channel for children’s clothing. On the other hand, the facilitators for consumers using OCRPs were identified as psychological capability, physical opportunity, and reflective motivation, which motivated and facilitated their adoption of OCRPs for clothing disposal. Therefore, H8 is supported by the qualitative findings.

Based on the frequency of consumer’s avoidance and use of OCRPs and by mapping to the COM components, the frequency of capability, opportunity, and motivation factors were generated, as shown in

Table 5. To determine whether significant differences existed among capability, opportunity, and motivation factors, the Chi-square test was used for count data. As shown in

Table 6, the results of the Chi-square test indicate that there were significant differences between the three COM components with regard to use or avoidance of OCRPs (Chi

2 = 55.797;

p < 0.001). To determine the specific significant relationship between behavioral categories, a pairwise comparison of groups was performed using the Chi-square partition method.

As shown in

Table 6, the difference in using OCRPs among COM component factors was significant. As indicated by subscript letters, the proportion of consumers who used OCRPs in the opportunity component (77.8%) was significantly higher than that in capability component (17.8%) and motivation component (4.4%). Meanwhile, the difference in avoiding OCRPs among the three component factors was also significant. The proportion of the capability component (56.3%) was significantly higher than that of the motivation component (22.1%) and the opportunity component (21.6%). Therefore, H9 is supported.

5. Discussion

The results of the mixed-method analysis shed light on the factors influencing consumers’ disposal behavior for children’s clothing through giving away and throwing away channels and also provide valuable insights into the reasons behind mothers’ use or avoidance of OCRPs as a disposal channel for children’s clothing.

5.1. Factors That Influence Consumers’ Choice of Conventional Disposal Channels for Children’s Clothing

The disposal reason related to poor fit was found to lead to the giving away channel rather than the throwing away option, indicating that consumers tend to dispose of children’s clothing in wearable condition through sustainable reuse channels. This suggests that children’s clothing in wearable condition is appropriately treated in China. On the other hand, the disposal reason concerning clothing damage was found to lead to the throw away channel and not to RRC. This indicates that children’s clothing in unsatisfactory condition is not properly treated in China. These findings align with Norum’s [

17] and Degenstein et al.’s [

7] studies, which found that size issues influence the reuse channel, whereas garment damage influences the throw away channel. The reasons for clothing damage include issues relating to wear and tear and stains. Even if clothing is in an unsatisfactory condition, consumers can prolong the life of the clothing by reprocessing, repurposing, or finding another use via reuse or recycling channels instead of throwing away [

52]. This may be because of limited awareness and knowledge regarding the disposal of damaged clothing through reuse or recycling channels in China, revealing potential gaps in education about the environmental and social advantages of clothing reuse and recycling. Additionally, there is a lack of clear guidance on disposal methods stemming from institutional promotion and policy-driven regulation. Consequently, raising awareness and educating consumers about diverse disposal methods based on clothing condition, highlighting the benefits of using RRC for unsatisfactory clothing, and enacting policies that regulate and encourage reuse and recycling practices becomes crucial.

The study also found that there was a significant difference in the choice of the giving away disposal channel depending on mothers’ ages. This is consistent with the findings of Laitala [

10], who found that older consumers tend to dispose of unwanted clothes more sustainably. Additionally, the study found that the choice of the throw away disposal channel varied based on the levels of annual family income, with higher-income families being more inclined to throw away clothing. This suggests that families with higher income may be less concerned about economic issues when disposing of clothing, leading them to prefer throwing away rather than reusing or recycling, possibly due to economic or convenience-driven factors [

6]. Moreover, their greater financial capabilities to purchase new clothing may contribute to the streamlined use of the throw away channel [

39]. These findings are in line with the results of Zhang et al. [

13], who also observed that clothing has a shorter lifespan as income increases.

In light of these findings, it is important to consider targeted educational activities and clothing reuse/recycling events that can engage more families, especially younger-age mothers and those with higher annual family income levels. By promoting the benefits of sustainable clothing disposal practices and raising awareness about the negative environmental impacts of excessive throwing away, such initiatives could encourage more families to opt for sustainable disposal channels. Furthermore, organizing community events and workshops on repairing or repurposing damaged clothing items or providing incentives for using sustainable disposal methods could also be effective at encouraging positive behavioral changes. By tailoring these efforts to specific demographic groups, we can foster a culture of responsible clothing disposal and contribute to a more sustainable environment.

Moreover, more than half of the respondents reported using recycling boxes in their communities, and no specific disposal reason was found to significantly impact this behavior. This suggests that community recycling boxes may serve as a multipurpose disposal channel, accepting both wearable and unwearable clothing items.

5.2. The Usage Status of OCRPs among Consumers and the Barriers and Facilitators for Their Adoption

The qualitative results regarding the current use status of OCRPs revealed that they were significantly less used by respondents, indicating that OCRPs are not widely accepted by consumers in China at present, which is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. [

13]. The primary barriers for using OCRPs were related to psychological capability, including unawareness of OCRPs and confusion about platform procedures. This suggests a lack of widespread promotion and education regarding OCRPs, which may hinder their adoption. Thus, widely disseminating the instruction of using OCRPs through widely used media channels is essential. On the other hand, environmentally and ethically conscious consumers were more likely to use OCRPs, indicating that consumer awareness and concerns about sustainability play a role in channel selection. This is consistent with the findings of Bianchi and Birtwistle [

53], who found that consumers’ environmental awareness influences reuse disposal channels. It also suggests that education for promoting environmental awareness is necessary, as education is the most effective intervention method for improving knowledge and awareness [

25].

Reflective motivation emerged as a strong barrier for using OCRPs, with alternative disposal options being a major concern for some consumers. This highlights the importance of providing consumers with clear instruction on using OCRPs and educating them about OCRPs’ benefits for the environment. According to the recommendations of Michie et al. [

25], educational interventions can effectively address intention issues related to the reflective motivation component of COM-B. By raising awareness and providing information about OCRPs, consumers can make more informed and environmentally conscious choices when disposing of children’s clothing. On the other hand, the findings also indicate that there are several options for disposing of children’s clothing. Reuse and recycling disposal channels may have duplicate functions, such as recycling boxes in communities and OCRPs, which could be integrated through government intervention and provide more convenient disposal outlets for children’s clothing that may be frequently disposed of or comprise small quantities. Privacy concerns were also identified, indicating the need for OCRP platforms to define and disclose privacy protections to address consumer apprehensions. Reflective motivation was also recognized as a facilitator for consumers using OCRPs, with reward-driven intention for usage being mentioned. This suggests that incentives and rewards could encourage sustainable disposal behavior and engagement with OCRPs, which is consistent with the findings of Joung and Park-Poaps [

6], who found that incentives and rewards encourage pro-environmental behavior.

Physical opportunity was identified as a significant facilitator for consumers using OCRPs, with convenient procedure and free usage being prominent factors. This indicates that the service provided by OCRPs facilitates consumer use if they are aware of this disposal channel, showcasing its developing potential. This finding is also in line with Zhang et al.’s [

13] findings, which showed that perceived usefulness influences consumers’ platform usage intentions. However, several barriers related to physical opportunity, such as weight limitation, complicated procedure, time constraints, and packing issues, were also noted. These barriers indicate that consumers had difficulties using OCRPs. This is consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. [

13], who found that low perceived ease of use decreases consumers’ platform usage intentions. Consequently, wider acceptance of OCRPs is also hindered by these difficulties, which should be resolved. According to Zhang and Hale [

26], implementing environmental restructuring and enabling intervention functions by the fashion industry and the government is crucial to address resources issues related to the physical opportunity component of COM-B.

Social opportunity emerged as a barrier to using OCRPs, with transparency concerns, supervision, and health hazards being concerns for some consumers. This indicates that consumers’ perceptions of social norms influence their behaviors [

25], which corresponds to Zhang et al. ‘s [

13] findings that subjective norms influence consumer intentions toward adopting OCRPs. This also suggests that the government holds the main responsibility for overcoming these barriers through supervision and formulating relevant specifications since behavioral changes must be accompanied by policy changes [

26].

Based on the findings, the comparison of capability, opportunity, and motivation factors influencing consumers’ behavior of using or avoiding OCRPs revealed that the capability and opportunity components are the most significant barriers to and facilitators for using OCRPs. This indicates that the most crucial strategy for promoting OCRPs is facilitating users’ capability, especially their awareness of this channel, and improving OCRP opportunity, especially the consideration of users’ experiences.

6. Conclusions

The study delved into the disposal behavior regarding children’s clothing, a topic often overlooked by researchers due to its unique nature compared to adults’ clothing. By investigating the factors influencing Chinese consumers’ choice of conventional disposal channels for children’s clothing and exploring the current usage status of OCRPs, along with barriers and facilitators for their adoption, this research contributes to a comprehensive understanding of sustainable clothing disposal practices.

The findings demonstrate that children’s clothing is disposed of through different channels, based on disposal reasons such as poor fit and clothing damage. This reveals that children’s clothing in wearable condition is typically given away, whereas unsatisfactory clothing is discarded via the throw away channel. Moreover, the study identified significant differences in the choice of disposal channel, with the giving away disposal channel being based on mothers’ ages and the throw away clothing disposal channel being dependent on family income levels. Furthermore, the research indicates that OCRPs as a potential disposal channel are not widely accepted among Chinese consumers due to barriers related to psychological capability, physical opportunity, social opportunity, and reflective motivation.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The theoretical implications of this study are noteworthy. Firstly, it addresses the research gap by investigating disposal behavior regarding children’s clothing, expanding the existing literature on sustainable clothing disposal practices. Secondly, it identifies the factors influencing the consumers’ choice of conventional disposal channels, including the reasons for disposal and individual characteristics of both children and parents, which provides a specific reference for formulating strategies to promote sustainable clothing disposal behavior. Thirdly, it highlights the differences in disposal features between children’s and adults’ clothing, shedding light on the unique aspects of disposal behavior regarding children’s clothing. Fourthly, our study explores the status of consumers using new disposal channels emerging in China, as well as the barriers to and facilitators for consumers using them; this extends conventional disposal channels in previous studies. Lastly, by incorporating the COM-B framework from behavioral science, the study enriches the understanding of sustainable clothing industry and sustainable consumption behavior research. It demonstrates the applicability of the COM-B framework to the study of clothing disposal behavior, an area that has not been extensively explored before.

6.2. Practical Implications

The practical implications of this research hold relevance to consumers, recyclers, public policymakers, and stakeholders in the children’s clothing industry, as formulating strategies to promote sustainable clothing disposal behavior is of utmost importance. Discouraging premature clothing disposal by encouraging sustainable disposal practices for children’s clothing, which has significant potential for reuse and recycling [

38,

39], can extend the lifespan of children’s clothing, leading to positive environmental impacts and improved clothing disposal awareness for future generations. Disposal of children’s clothing differs from that of adults’ clothing due to its unique characteristics, warranting the development of methods that encourage extended use, shared usage among multiple individuals, and avoidance of throwing away. It is worth noting that parents’ or guardians’ disposal behavior directly influences their children’s clothing consumption patterns, which in turn may impact the attitudes and behaviors of children when they become adults [

40]. Therefore, fostering responsible clothing disposal practices among parents and guardians can potentially create a lasting impact on future generations’ sustainable consumption behaviors.

Encouraging sustainable behavior for the disposal of children’s clothing, with a focus on reuse and recycling, can be effectively promoted through a range of educational programs, pro-environmental initiatives, and policy regulations. Incorporating lessons on sustainable consumption, recycling, and reuse in educational curricula at various levels can create a lasting impact by shaping the attitudes and behaviors of future generations. Institutions could launch awareness campaigns targeting both consumers and businesses, highlighting the environmental and social benefits of reusing and recycling clothing. Implementing regulations on textile waste reduction or mandates for clothing disposal processes could also contribute to sustainable disposal practices. Collaborative efforts between clothing-recycling platforms and schools or communities can lead to the development of regular clothing reuse and recycling events that engage diverse age groups and families with varying annual income levels. Community-driven activities like children’s clothing collection or swapping, along with workshops on clothing repair and repurposing, can further promote sustainable clothing disposal practices among families.

To raise awareness about new disposal channels, social media platforms such as WeChat, TikTok, Bilibili, and Little Red Book [

54], which are widely used in China, can be leveraged to share information about OCRPs and their benefits. Entrepreneurs in the field of children’s clothing could promote the usage of recycled material by cooperating with OCRPs and supporting OCRPs by introducing incentive programs that reward parents for using OCRPs, such as offering discounts on future purchases, coupons, or brand points. Policymakers should also play a crucial role in supervising OCRPs and regulating recycling channels with similar functions, either through integration or division of labor, to provide refined disposal channels for different types of clothing. Classifying clothing based on disposal criteria can maximize recycling effectiveness across all recycling channels. For example, specific recycling targets such as children’s clothing should be set based on the grading of clothing conditions and designated to a certain disposal channel to maximize the recycling effectiveness and bridge the gap between supplier (users) and demander. Thus, consumer education, facilitated by strategies in the field of clothing disposal, needs to expand along with empowering consumers to consider the environment when disposing of clothing.

Furthermore, in light of the frequent updates in children’s clothing sizes and the ease with which children’s clothing can be worn out and stained, which could cause an environmental impact, children’s clothing enterprises can contribute to sustainability efforts by launching products designed for extended lifespans, such as adjustable sizes, stronger materials, or improved dirt-resistant effects. Additionally, collaboration between clothing manufacturers and recycling firms can promote closed-loop production and the recycling of clothing materials.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into sustainable disposal behavior regarding children’s clothing and offers practical strategies for promoting sustainable clothing disposal practices. By focusing on the unique characteristics of children’s clothing and tailoring efforts to specific demographic groups, a culture of responsible clothing disposal can be fostered, contributing to a more sustainable context.

7. Limitations and Further Study

Despite being an exploratory study with specific objectives related to behavior regarding the disposal of children’s clothing, this study has some limitations. Firstly, the results may not be universally applicable worldwide due to geographic limitations and the influence of China’s unique cultural context regarding certain behaviors and conditions. The cultural factors specific to China may not be suitable for generalization to other countries with different cultural norms and practices.

Secondly, the findings of this study might not be generalizable to populations with wider age ranges, as the research samples were limited to mothers of children within specific age ranges. Moreover, the data collection was confined to a select number of cities in northern China, potentially offering an incomplete representation of the broader spectrum of Chinese consumers. Furthermore, the study’s focus on urban areas may inadvertently have led to oversight of valuable insights that are pertinent to rural contexts. To address these, expanding the participant pool to encompass a broader range of age groups bolstered by a larger sample size and encompassing diverse geographic regions could facilitate the comprehensiveness of our insights into behavior regarding the disposal of children’s clothing.

Thirdly, the survey results on disposal practices did not delve into more specific behaviors, such as disposal frequency and quantity. Additionally, the data were not subdivided based on various attributes of children’s clothing, such as clothing type, material composition, price, brand, and number of users. Further research that delves into these specific aspects could provide deeper insights into the factors influencing clothing disposal decisions.

For future studies, it is essential to consider a wider range of factors that might influence consumer behavior regarding the disposal of children’s clothing. Additional variables could be incorporated to gain a more comprehensive understanding of disposal behavior in different contexts.

Moreover, employing more advanced research methods, such as wardrobe studies or qualitative interviews, could provide in-depth and specific insights into the complexities of clothing disposal behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and E.K.; methodology, W.G. and E.K.; investigation, W.G.; data curation, W.G.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G.; writing—review and editing, W.G. and E.K.; supervision, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) Kaken (funding No. KAKEN 22K13754), Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was conducted in a commonly accepted consumption setting.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the 259 participants who generously donated their time and information to make this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yan, R.N.; Diddi, S.; Bloodhart, B. Predicting Clothing Disposal: The Moderating Roles of Clothing Sustainability Knowledge and Self-Enhancement Values. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 3, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.B.; Choo, H.J. An Action Research on Creative Clothing Consumption Behavior. J. Korean Soc. Cloth. Text. 2016, 44, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, H.; Sarigöllü, E.; Xu, W. Nostalgia Prompts Sustainable Product Disposal. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwistle, G.; Moore, C.M. Fashion clothing–where does it all end up? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, H.M.; Park-Poaps, H. Factors motivating and influencing clothing disposal behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenstein, L.M.; McQueen, R.H.; Krogman, N.T. ‘What goes where’? Characterizing Edmonton’s municipal clothing waste stream and consumer clothing disposal. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen Macarthur Foundation (EMF). A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. Volume 150. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Textile Exchange. Preferred Fiber & Materials, Market Report. Available online: https://textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Laitala, K. Consumers’ Clothing Disposal Behaviour—A Synthesis of Research Results. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Cárdenas, J.; Guadalupe-Lanas, J.; Velín-Fárez, M. Consumer Value Creation through Clothing Reuse: A Mixed Methods Approach to Determining Influential Factors. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenstein, L.M.; McQueen, R.H.; McNeill, L.S.; Hamlin, R.P.; Wakes, S.J.; Dunn, L.A. Impact of Physical Condition on Disposal and End-of-Life Extension of Clothing. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, T.; Liu, S.; Jiang, S.; Wu, H.; Yang, J. Consumers’ Clothing Disposal Behaviors in Nanjing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepp, I.G.; Storm-Mathisen, A. Reading fashion as age: Teenage girls’ and grown women’s accounts of clothing as body and social status. Fash. Theory 2005, 9, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K. Clothing Sharing for Efficiency Use of the Children’s Clothing in a Sharing Economy. J. Korean Soc. Cloth. Text. 2017, 41, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sego, T. Mothers’ experiences related to the disposal of children’s clothing and gear: Keeping mister clatters but tossing broken barbie. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norum, P.S. Trash, Charity, and Secondhand Stores: An Empirical Analysis of Clothing Disposition. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2015, 44, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spuijbroek, M.; Textile Waste in Mainland China. An Analysis of the Circular Practices of Post-Consumer Textile Waste in Mainland China. Available online: https://www.netherlandsandyou.nl/documents/publications/2019/08/08/textile-waste-in-mainland-china (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Guo, W.; Kim, E. Categorizing Chinese Consumers’ Behavior to Identify Factors Related to Sustainable Clothing Consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai Yee, L.; Hassan, S.H.; Ramayah, T. Sustainability and Philanthropic Awareness in Clothing Disposal Behavior Among Young Malaysian Consumers. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 2158244015625327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Cárdenas, J.; Arévalo-Chávez, P. Consumer Behavior in the Disposal of Products: Forty Years of Research. J. Promot. Manag. 2018, 24, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, S.A.; Horne, S.; Tagg, S. Charity retailers in competition for merchandise: Examining how consumers dispose of used goods. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.W. A proposed paradigm for consumer product disposition processes. J. Consum. Aff. 1980, 14, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Berning, C.K.; Dietvorst, T.F. What about disposition? J. Mark. 1977, 41, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions, 1st ed.; Silverback Publishing: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Hale, J. Extending the lifetime of clothing through repair and repurpose: An investigation of barriers and enablers in UK citizens. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Halter, H.; Johnson, K.K.; Ju, H. Investigating fashion disposition with young consumers. Young Consum. 2013, 14, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Kim, E. A study of sustainable design methods for clothing recycling from the perspective of reverse thinking. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference of the European Academy of Design (EAD 2021), Lancaster, UK, 12–15 October 2021; pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Laitala, K.; Boks, C. Sustainable clothing design: Use matters. J. Des. Res. 2012, 10, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharuddin, S.S.; Jalil, M.H.; Moghadasi, K. Study of Mechanical Properties and Characteristics of Eco-Fibres for Sustainable Children’s Clothing. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2021, 31, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, M.A.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Ponce-Cueto, E. Developing a national programme for textiles and clothing recovery. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Cárdenas, J.; González, R.; Gascó, J. Clothing Disposal System by Gifting: Characteristics, Processes, and Interactions. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2017, 35, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwozdz, W.; Nielsen, K.S.; Müller, T. An environmental perspective on clothing consumption: Consumer segments and their behavioral patterns. Sustainability 2017, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, Y.; Tian, X.; Gong, Y. Urban Household Solid Waste Generation and Collection in Beijing, China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.; Perera, B. From trash to treasure and beyond: The meaning of voluntary disposition. J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Choi, H.-S.; Hee Do, W. A Study of the Apparel Sizing of Children’s Wear. J. Korean Home Econ. Assoc. Engl. Ed. 2001, 2, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimäki, K.; Kujala, S.; Karell, E.; Lang, C. Sustainable Product-Service Systems for Clothing: Exploring Consumer Perceptions of Consumption Alternatives in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.; Hill, H.; Kininmonth, J.; Townsend, K.; Hughes, M. Design for Longevity: Guidance on Increasing the Active Life of Clothing; Waste and Resources and Action Programme: Banbury, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, C.; Armstrong, C.M.; Brannon, L.A. Drivers of Clothing Disposal in the US: An Exploration of the Role of Personal Attributes and Behaviours in Frequent Disposal. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizou, P.; Henninger, C.E.; Stokoe, J.; Cheng, R. The hoarder, the oniomaniac and the fashionista in me: A life histories perspective on self-concept and consumption practices. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, N. Sizing System for Functional Clothing—Uniforms for School Children. Indian. J. Fibre Text. Res. 2011, 36, 348–357. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B.J.; Sego, T. The role of identity in disposal: Lessons from mothers’ disposal of children’s possessions. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, G.D.; McConocha, D.M. Personal factors related to consumer product disposal tendencies. J. Consum. Aff. 1992, 26, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S. Environmentalism and consumers’ clothing disposal patterns: An exploratory study. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1995, 13, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wagenaar, D.; Galama, J.; Sijtsema, S.J. Exploring worldwide wardrobes to support reuse in consumers’ clothing systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shloim, N.; Edelson, L.R.; Martin, N.; Hetherington, M.M. Parenting styles, feeding styles, feeding practices, and weight status in 4–12 year-old children: A systematic review of the literature. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 6th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe, J.T. Fundamental Research Statistics for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Holt Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, L.J.; Powell, R.; French, D.P. How can use of the theoretical domains framework be optimized in qualitative research? a rapid systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, L. Qualitative research proposals—Part II: Conceptual models and methodological options. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2007, 34, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwilt, A. A Practical Guide to Sustainable Fashion; Fairchild Publications: London, UK, 2014; pp. 30–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Consumer clothing disposal behaviour: A comparative study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Fung, B.C.M.; Chen, Z. Young Chinese consumers’ choice between product-related and sustainable cues-the effects of gender differences and consumer innovativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).