The Impact of Proactive Resilience Strategies on Organizational Performance: Role of Ambidextrous and Dynamic Capabilities of SMEs in Manufacturing Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resilience and Ambidexterity

2.2. Organizational Performance

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Proactive Resilience Strategies and Organizational Performance

3.2. Visibility (VS) and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.3. Predefined Decision Plan (PD) and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.4. Proactive Resilience Strategies and Ambidexterity Capabilities

3.5. Visibility (VS) and Exploitation Capability (EI)

3.6. Visibility (VS) and Exploration Capability (ER)

3.7. Predefined Decision Plan (PD) and Exploitation Capability (EI)

3.8. Predefined Decision Plan (PD) and Exploration Capability (ER)

3.9. Ambidextrous Capabilities and Organizational Performance

3.10. Exploitation Capability (EI) and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.11. Exploration Capability (ER) and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.12. Relationship between Visibility (VS), Exploitation Capability (EI) and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.13. Relationship between Visibility (VS), Exploration Capability (ER), and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.14. Relationship between Predefined Decision Plan (PD), Exploitation Capability (EI), and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.15. Relationship between Predefined Decision Plan (PD), Exploration Capability (ER), and Organizational Performance (OP)

3.16. Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT)

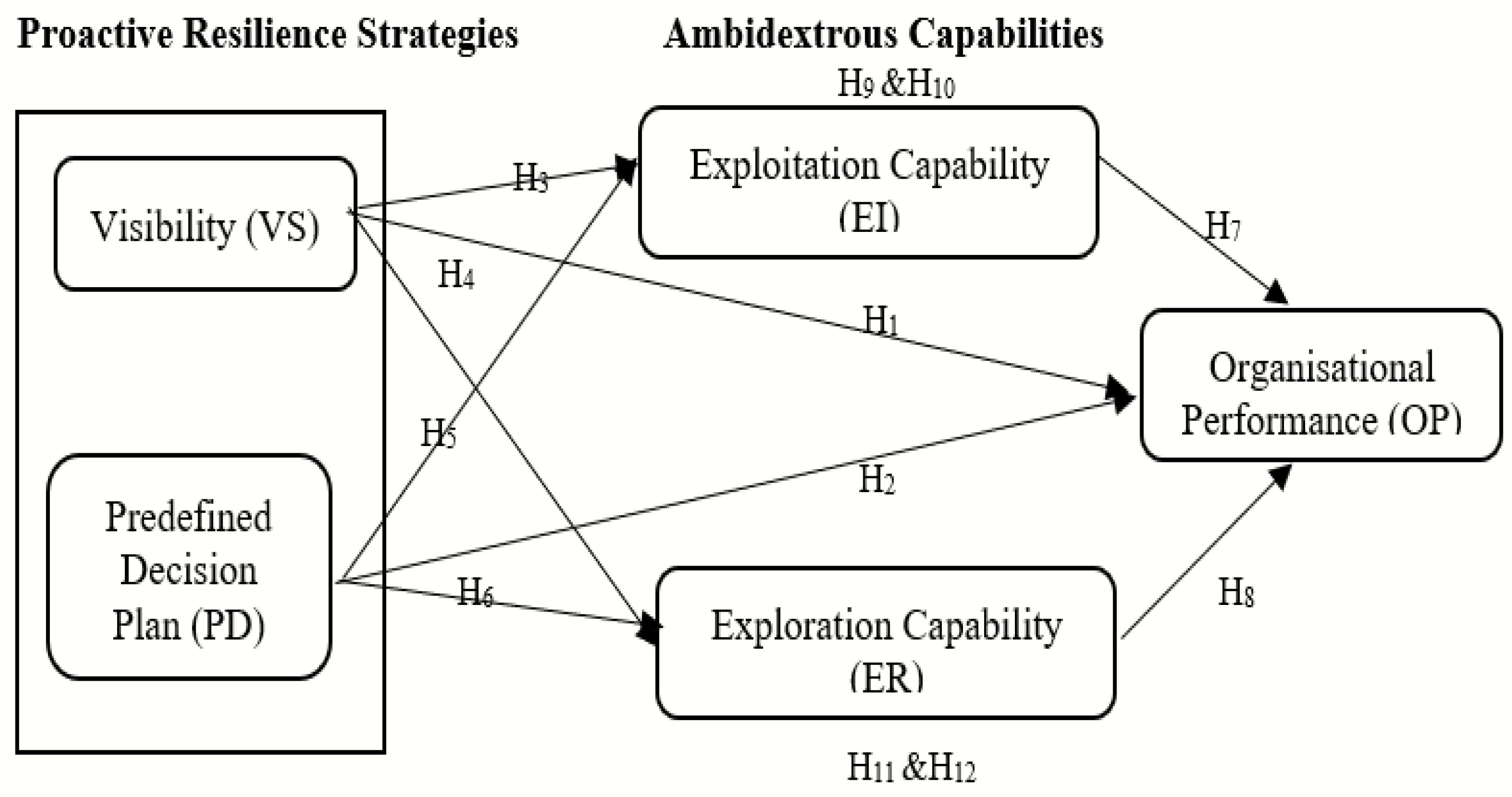

3.17. Research Framework

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Questionnaire and Pre-Testing

4.2. Sample Design and Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

Common Method Bias

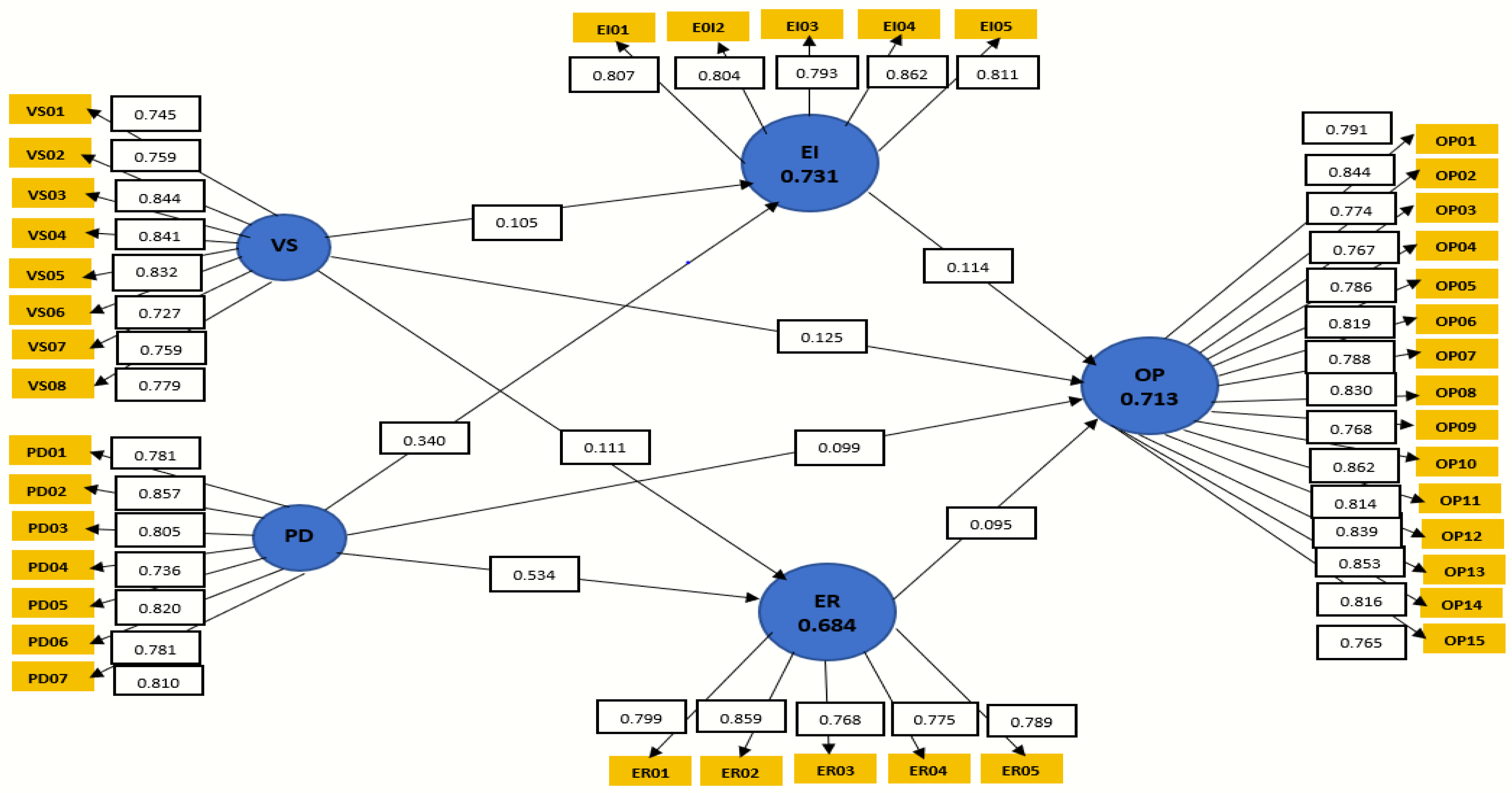

4.4. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.5. Assessment of the Structural Model

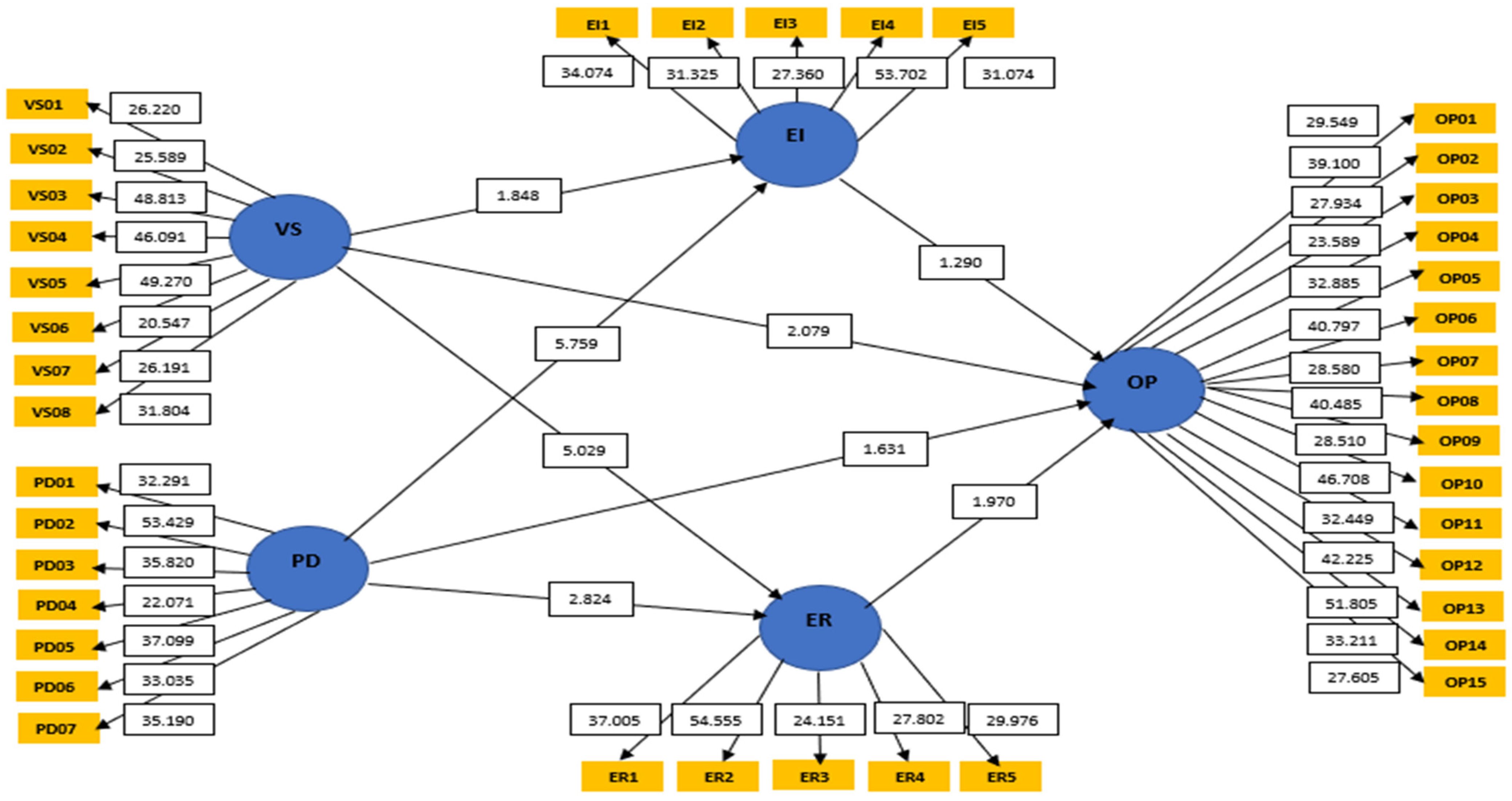

4.6. Path Analysis

4.7. Specific Indirect Effects

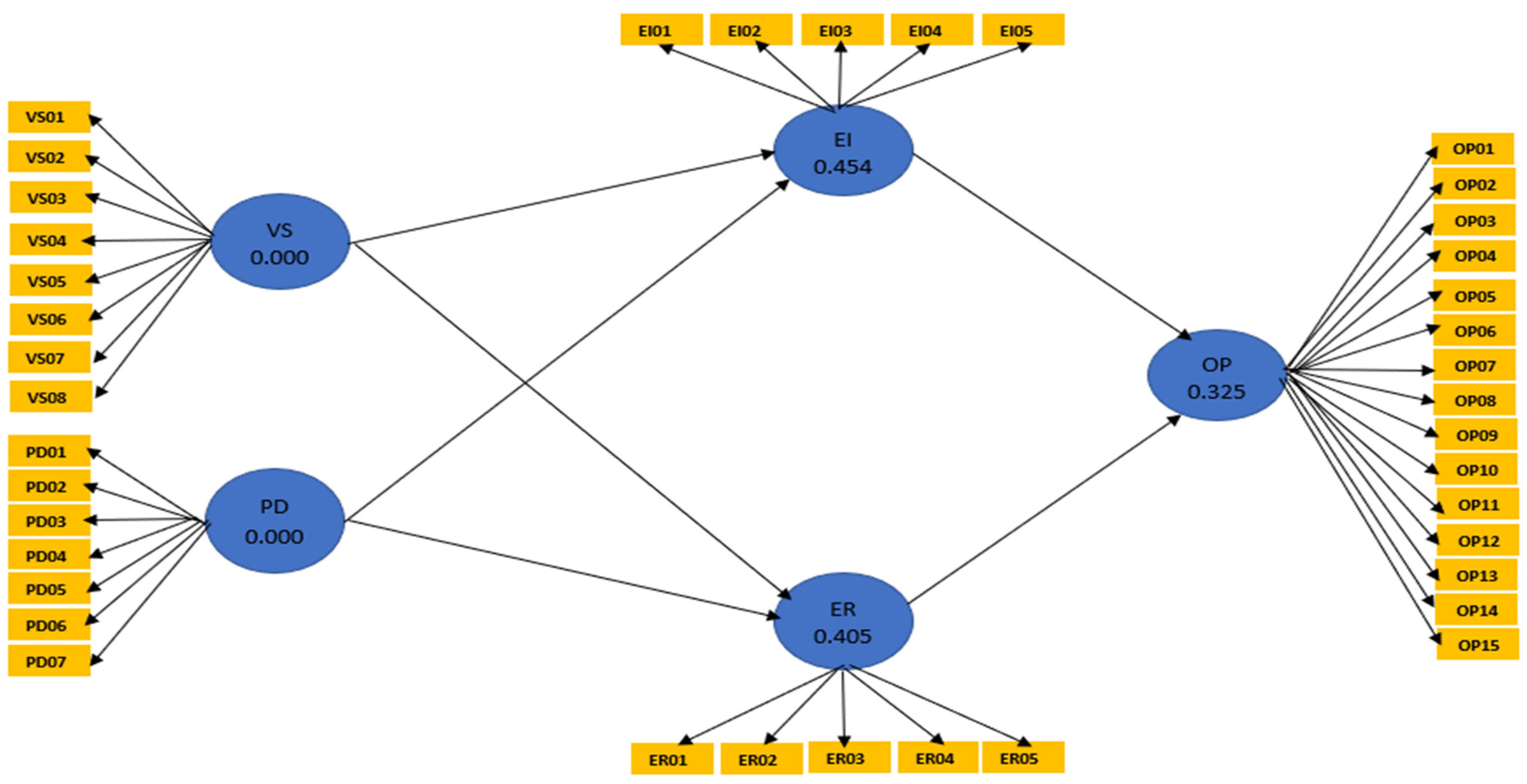

4.8. Predictive Relevance

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations of Study

5.4. Future Research Directions

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Items Visibility | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharing supply chain related issues for better improvement | |||||

| Finding major opportunities in our supply chain activities | |||||

| Having good observation and judgment ability in our supply chain activities | |||||

| Continuously improves our supply chain process | |||||

| Having better information sharing for future strategic needs | |||||

| Understand customer demand better than competitors do | |||||

| Collaborate to monitor supply chain activities | |||||

| Kept informed of customer’s future demand | |||||

| Predefined Decision Plan | |||||

| Make timely decisions in supply chain process under any circumstance | |||||

| Frequent meetings to discuss the market demand | |||||

| Able to quickly reduce manufacturing lead-time to fulfill customer demand | |||||

| Able quickly improve supply chain responsiveness towards current market needs | |||||

| Able to deal with supply chain conflicts timely and in effective way | |||||

| Able to align (or re-distribute) skills to meet the current needs of the whole supply chain | |||||

| Able realign (reinvent) supply chain process accordance to market needs | |||||

| Able to share supply chain information with our business partners to address problems more effectively | |||||

| Exploration | |||||

| Constantly leveraging current supply chain technology for better improvement | |||||

| Focuses on developing strong competencies in existing supply chain process | |||||

| Proactively pursues new supply chain solutions | |||||

| Continuously explores new opportunities in supply chain process | |||||

| Constantly seeks novel approaches in order to solve supply chain problems | |||||

| Exploitation | |||||

| Able to increase economies of scale in existing markets by focusing on supply chain activities | |||||

| Frequently utilizes new opportunities in markets by improving supply chain practices | |||||

| Concerned about continuous improvement of supply chain process for better performance | |||||

| Continuously monitoring supply chain activities to maintain quality performance | |||||

| Continuously communicating with supply chain partners for better performance | |||||

| Organizational Performance | |||||

| Able to achieve better product quality by improving supply chain processes | |||||

| Able achieve better product by focusing on innovative idea in supply chain processes | |||||

| Technology enhancement in supply chain practices will eventually lead to higher market share | |||||

| constantly lowers product cost by focus on supply chain processes | |||||

| Concerned about cost factor in every supply chain process and stages | |||||

| Able to respond fast to customer by improving supply chain processes | |||||

| Integration between various departments to helps to reduce the departmental barrier | |||||

| Close relationship with suppliers will help to improve supply chain activities | |||||

| Increasing coordination with customer will help to improve overall performance | |||||

| Continues improvement in supply chain practices will lead to increase in sales | |||||

| Ability to monitor production and service process to improve quality | |||||

| Able to analyze work processes and systems for better customer service | |||||

| Concerned about continuous quality improvement in supply chain planning process | |||||

| Able to understands customers’ needs and response accordingly | |||||

| Having capability to incorporate quality factors in product design |

References

- Scholten, K.; Stevenson, M.; van Donk, D.P. Dealing with the unpredictable: Supply chain resilience. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yuan, J.; Pan, J. Why SMEs in emerging economies are reluctant to provide employee training: Evidence from China. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L.; Melin, L.; Naldi, L. Dynamics of business models–strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, G.K.; Gupta, M.C.; Cheng, T.C.E. The effects of strategic orientation on operational ambidexterity: A study of Indian SMEs in the industry 4.0 era. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 220, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, J.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Approaches for resilience and antifragility in collaborative business ecosystems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 151, 119846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juttner, U.; Maklan, S. Supply chain resilience in the global financial crisis: An empirical study. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2011, 16, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Akter, S. The performance effects of big data analytics and supply chain ambidexterity: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 222, 107498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, I.; Dhir, S. Organizational ambidexterity from the emerging market perspective: A review and research agenda. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 64, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Passas, I.; Garefalakis, A.; Dimou, I. Investigating the research trends on strategic ambidexterity, agility, and open innovation in SMEs: Perceptions from bibliometric analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, U.; Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A.; Maseda, A.; Iturralde, T. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation in family SMEs: Unveiling the (actual) impact of the Board of Directors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, J. Building capacity for sustainable innovation: A field study of the transition from exploitation to exploration and back again. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, I.; Kalyar, M.N.; Mehwish, N. Organizational ambidexterity, green entrepreneurial orientation, and environmental performance in SMEs context: Examining the moderating role of perceived CSR. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdan, M.R.; Abd Aziz, N.A.; Abdullah, N.L.; Samsudin, N.; Singh, G.S.; Zakaria, T.; Fuzi, N.M.; Ong, S.Y. SMEs performance in Malaysia: The role of contextual ambidexterity in innovation culture and performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammassis, C.S.; Kostopoulos, K.C. CEO goal orientations, environmental dynamism and organizational ambidexterity: An investigation in SMEs. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, K.M.; Sok, P.; Tsarenko, Y.; Widjaja, J.T. How and when frontline employees’ resilience drives service-sales ambidexterity: The role of cognitive flexibility and leadership humility. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 5, 2965–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaxylyk, S. Organizational ambidexterity and resilience: Empirical evidence from uncertain transition economic context. Pressacademia 2020, 11, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Rha, J.S. Ambidextrous supply chain as a dynamic capability: Building a resilient supply chain. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, C.G.; Nowicki, D.R. Supply chain resilience: A systematic literature review and typological framework. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 842–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Patil, P.P.; Liu, S. When challenges impede the process: For circular economy-driven sustainability practices in food supply chain. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurksiene, L.; Pundziene, A. The relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltantawy, R.A. The role of supply management resilience in attaining ambidexterity: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.J.; Silva, G.M.; Sarkis, J. Exploring the relationship between quality ambidexterity and sustainable production. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 224, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Tajvidi, M.; Gbadamosi, A.; Nadeem, W. Understanding market agility for new product success with big data analytics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 86, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putritamara, J.A.; Hartono, B.; Toiba, H.; Utami, H.N.; Rahman, M.S.; Masyithoh, D. Do Dynamic Capabilities and Digital Transformation Improve Business Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from Beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Zhou, A.J.; Feng, J.; Jiang, S. Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: The mediating role of innovation. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.A.; Borsato, M. Organizational performance and indicators: Trends and opportunities. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 1, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatrooshi, B.; Singh, S.K.; Farouk, S. Determinants of organizational performance: A proposed framework. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 844–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dou, R.; Muddada, R.R.; Zhang, W. Management of a holistic supply chain network for proactive resilience: Theory and case study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 1, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalah, S.; Raman, M.; Marthandan, G.; Logeswaran, A.K. Implementation of enterprise risk management (ERM) framework in enhancing business performances in oil and gas sector. Economies 2018, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein, N.O.; Feisal, E.; Hartmann, E.; Giunipero, L. Research on the phenomenon of supply chain resilience: A systematic review and parts for further investigation. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, K.; Asare-Bediako, E.; Jacqueline, A.P. Effects of Supply Chain Visibility on Supply Chain Performance in Ghana Health Service: The Case of Kumasi Metro Health Directorate. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 11, 437–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Jajja, M.S.; Chatha, K.A.; Farooq, S. Supply chain risk management and operational performance: The enabling role of supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalla-Luque, R.; Machuca, J.A.; Marin-Garcia, J.A. Triple-A and competitive advantage in supply chains: Empirical research in developed countries. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 203, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.D.; Roh, J.; Tokar, T.; Swink, M. Leveraging supply chain visibility for responsiveness: The moderating role of internal integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.; Schöggl, J.P.; Reyes, T.; Baumgartner, R.J. Sustainable product development in a circular economy: Implications for products, actors, decision-making support and lifecycle information management. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakara, A.M.; Elrehail, H.; Alatailat, M.A.; Elc, A. Knowledge management, decision-making style and organizational performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 4, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarng, K.; Mas-Tur, A. New knowledge impacts in designing implementable innovative realities. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, A.; Voola, R.; Yuksel, U. The dynamic capability of ambidexterity in hypercompetition: Qualitative inisghts. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jacobs, M.A.; Chavez, R.; Yang, J. Dynamism, disruption orientation, and resilience in the supply chain and the impacts on financial performance: A dynamic capability perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 218, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Perrigino, M.B. Resilience: A review using a grounded integrated occupational approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 729–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Organizational resilience and employee work-role performance after a crisis situation: Exploring the effects of organizational resilience on internal crisis communication. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglam, Y.C.; Cankaya, S.Y. Proactive risk mitigation strategies and supply chain risk management performance: An empirical analysis for manufacturing firms in Turkey. J. Manuf. 2021, 32, 1224–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Kallinger, F.L.; Bican, P.M.; Brem, A.; Kailer, N. Organizational ambidexterity and competitive advantage: The role of strategic agility in the exploration-exploitation paradox. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Hu, A. Big Data Capability and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Innovation Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 18249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocicka, B.; Mierzejewska, W.; Brzezinski, J. Creating supply chain resilience during and post COVID-19 outbreak: The organisational ambidexterity perspective. Decision 2022, 49, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, F.; Jia, F.; Chen, L. Building supply chain resilience through ambidexterity: An information processing perspective. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 26, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzidia, S.; Makaoui, N.; Subramanian, N. Impact of ambidexterity of blockchain technology and social factors on new product development: A supply chain and Industry 4.0 perspective. Sciencedirect 2021, 169, 120819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V. Contrasting supply chain traceability and supply chain visibility: Are they interchangeable? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 942–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalah, S.; Raman, M.; Marthandan, G.; Logeswaran, A.K. Embracing technology and propelling SMEs through open innovation transformation. Int. J. Financ. Insur. Risk Manag. 2020, 10, 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Vilko, J.; Ritala, P.; Hallikas, J. Risk management abilities in multimodal maritime supply chains: Visibility and control perspectives. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annamalah, S.; Aravindan, K.L.; Raman, M.; Paraman, P. SME Engagement with Open Innovation: Commitments and Challenges towards Collaborative Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.S.; Venkatesh, M.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Benkhati, I. Building supply chain resilience and efficiency through additive manufacturing: An ambidextrous perspective on the dynamic capability view. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 249, 108516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanzadeh, S.; Pishvaee, M.S.; Rasouli, M.R. A robust fuzzy-stochastic optimization model for managing open innovation uncertainty in the ambidextrous supply chain planning problem. Soft Comput. 2022, 27, 6345–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reischl, A.; Weber, S.; Fischer, S.; Lang-koetz, C. Contextual ambidexterity: Tackling the Exploitation and Exploration dilemma of innovation management in SMEs. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2022, 19, 2250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, T.A.; Blome, C.; Papadopoulos, T. Driving NPD performance in high-tech SMEs through IT ambidexterity: Unveiling the influence of leadership decision making styles. In Proceedings of the 27th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Stockholm & Uppsala, Sweden, 8–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, M. Exploring the antecedents of ambidexterity: A taxonomic approach. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1489–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. Organisational ambidexterity and firm performance: Burning research questions for marketing scholars. J. Mark. Manag. 2018, 34, 178–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozic, K.; Dimovaski, V. Business intelligence and analytics use, innovation ambidexterity, and firm performance: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, B.D. Exploitation, ambidexterity and firm performance: A meta-analysis. In Exploration and Exploitation in Early Stage Ventures; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, M.; Micheli, P.; Longo, M. The effect of performance measurement system users on ambidexterity and firm performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.Y.P.; Lin, K.H. Disentangling the antecedents of the relationship between organisational performance and tensions: Exploration & Exploitation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. 2021, 32, 574–590. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, re-conceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, U.; Castillo-Apraiz, J.; Palma-Ruiz, J.M. Organisational learning as a mediator in the host-home country similarity-International firm performance link: The role of exploration and exploitation. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 33, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E.; Harvey, W. Managing exploration and exploitation paradoxes in creative organisations. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.H.; Lee, K.C.; Seo, Y.W. How does six sigma influence creativity and corporate performance through exploration and exploitation? Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, M.; Bedford, D.S. The role of market devices in addressing labour exploitation: Analysis of the Australian Cleaning Industry. Br. Account. Rev. 2023, 55, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, D.S.; Bisbe, J.; Sweeney, B. Performance measurement systems as generators of cognitive conflict in ambidextrous firms. Account. Organ. Soc. 2019, 72, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegan, M.F.; Nudurupati, S.S.; Childe, S.J. Predicting performance—A dynamic capability view. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 2192–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamayreh, E.M.; Sweis, R.J.; Obeidat, B.Y. The relationship among innovation organisational ambidexterity and organisational performance. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2019, 19, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Katic, M.; Cetindamar, D.; Agarwal, R. Deploying ambidexterity through better management practices: An investigation based on high-variety, low-volume manufacturing. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 952–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsjah, F.; Yunus, E.N. Achieving Supply Chain 4.0 and the Importance of Agility, Ambidexterity, and Organizational Culture: A Case of Indonesia. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Yang, L.; Huo, B. The impact of information technology usage on supply chain resilience and performance: An ambidextrous view. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 232, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Shan, S.; Shou, Y.; Kang, M. Sustainable sourcing and agility performance: The moderating effects of organizational ambidexterity and supply chain disruption. Aust. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.; Khan, A.Q.; Rashid, K.; Rehman, S. Achieving supply chain resilience: The role of supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain agility. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 1185–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib, A.W. Internet of things, big data analytics and operational performance: The mediating effect of supply chain visibility. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 34, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severgnini, E.; Vieira, V.A. The indirect effects of performance measurement system and organizational ambidexterity on performance. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1176–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Mani, V. Analyzing the mediating role of organizational ambidexterity and digital business transformation on industry 4.0 capabilities and sustainable supply chain performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2022, 27, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S.; Nakagawa, K. The Interplay of Digital Transformation and Collaborative Innovation on Supply Chain Ambidexterity. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.H.; Ellegaard, C.; Kragh, H. How purchasing departments facilitate organizational ambidexterity. Manag. Oper. 2021, 32, 1384–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, D.; Acharya, C.; Cooper, D. Transformational leadership and supply chain ambidexterity: Mediating role of supply chain organizational learning and moderating role of uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejardin, M.; Raposo, M.L.; Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I.; Veiga, P.M.; Farinha, L. The impact of dynamic capabilities on SME performance during COVID-19. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 28, 1703–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The foundations of enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms’ “v”. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamerew, Y.A.; Brissaud, D. Modelling reverse supply chain through system dynamics for realizing the transition towards the circular economy: A case study on electric vehicle batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Pingle, S. Mitigate supply chain vulnerability to build supply chain resilience using organisational analytical capability: A theoretical framework. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2020, 8, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yan, D.; Umair, M. Assessing the role of competitive intelligence and practices of dynamic capabilities in business accommodation of SMEs. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Lazim, H.M.; Iteng, R. The Effect of Product Innovation and Technology Orientation on the Firm Performance: Evidence from the Manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises of Pakistan. South Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 2, 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, J.; Raza, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Minai, M.S.; Bano, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Business Networks on Firms’ Performance Through a Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H.; Aftab, J.; Ishaq, M.I.; Atif, M. Achieving business competitiveness through corporate social responsibility and dynamic capabilities: An empirical evidence from emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, R.; Zailani, S.H.; Iranmanesh, M.; Rajagopal, P. The effects of vulnerability mitigation strategies on supply chain effectiveness: Risk culture as moderator. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh SC, L.; Demirbag, M.; Bayraktar, E.; Tatoglu, E.; Zaim, S. The impact of supply chain management practices on performance of SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2007, 107, 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, J.; Bhattacharyya, S. Measuring organizational performance and organizational excellence of SMEs Part 1: A conceptual framework. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2010, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Classroom Companion: Business; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling; SAGE Publication Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Next-generation prediction metrics for composite-based PLS-SEM. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size-or why the p value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* Power Software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V.; Valentine, J.C. (Eds.) Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Russell Sage Foundation: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B. How many subjects does it take to do a regression analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1991, 26, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Kelley, K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, A.; Linderman, K.; Schroeder, R. Antecedents to ambidexterity competency in high technology organizations. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunscheidel, M.J.; Suresh, N.C. The organizational antecedents of a firm’s supply chain agility for risk mitigation and response. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H.; Lundan, S.M. The institutional origins of dynamic capabilities in multinational enterprises. Ind. Corp. Change 2010, 19, 1225–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobler, A. A dynamic view on strategic resources and capabilities applied to an example from the manufacturing strategy literature. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2007, 18, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, T. Processes, antecedents and outcomes of dynamic capabilities. Scand. J. Manag. 2014, 30, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Sanchez-Vidal, M.E.; Cegarra-Leiva, D. Balancing exploration and exploitation of knowledge through an unlearning context: An empirical investigation in SMEs. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1099–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Legenvre, H.; Kalchschmidt, M. Exploration and exploitation within supply networks: Examining purchasing ambidexterity and its multiple performance implications. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s Dilemma. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdan, M.R.; Abdullah, N.C.; Hanafiah, M.H. Organizational ambidexterity within supply chain management: A scoping review. Sci. J. Logist. 2021, 17, 531–546. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, R.; Ling, H.; Zhang, C. Effect on business process management on firm performance: An ambidexterity perspective [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the International Conference Business Management and Electronic Information (BMEI), Guangzhou, China, 13–15 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.; Kortmann, S. On the importance of mediating dynamic capabilities for ambidextrous organizations. Procedia Cirp. 2014, 20, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present and future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Tsai, F.M.; Tseng, M.; Tan, R.R.; Yu, K.D.S.; Lim, M.L. Sustainable supply chain management towards disruption and organizational ambidexterity: A data driven analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 26, 373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J.; Kohtamaki, M.; Patel, P.C.; Parida, V. Supply chain ambidexterity and manufacturing SME performance: The moderating roles of network capability and strategic information flow. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.A. Management and Organization Theory: A Jossey-Bass Reader; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gawankar, S.A.; Gunasekaran, A.; Kamble, S. A study on investments in the big data-driven supply chain, performance measures and organisational performance in Indian retail 4.0 context. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1574–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation exploration tension organisational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. Understanding dynamic capabilities: Progress along a development path. Strateg. Organ. 2009, 7, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E.; Plümper, T. Robustness Tests for Quantitative Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Proactive Strategy | Readiness Elements | Sub-Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Proactive strategy | Collaboration | Coordination, cooperation, joint decision-making, knowledge sharing, supplier certification, supplier development |

| Human resource Management | Employee training and education, risk-sensitive culture and mindset, cross-functional teams, experienced employees for crisis management | |

| Inventory management Predefined decision Plans | Use of inventory and safety stocks to buffer disruptions, Contingency plans, communication protocols | |

| Redundancy | Production slack, transportation capacities, multiple sourcing and production locations | |

| Visibility | Early warning communication, information sharing, real-time and financial monitoring | |

| Reactive strategy | Response, recovery and growth elements | Sub-elements |

| Agility | Communication, information sharing (¼ visibility), quick supply chain redesign, velocity | |

| Collaboration | Coordination, cooperation, joint decision-making, knowledge sharing, supplier certification, supplier development | |

| Flexibility | Backup suppliers, easy supplier switching, distribution channels, flexible production systems, volume flexibility, multi-skilled workforces | |

| Human resource Management | Employee training and education, risk-sensitive culture and mindset, cross-functional teams, experienced employees for crisis management | |

| Redundancy | Production slack, transportation capacities, multiple sourcing and supplier locations |

| Measures | Description |

|---|---|

| Visibility (VS) | Information exchanged or addressed as the capability to access or share information across the supply chain and apply it in real time |

| Predefined decision plan (PD) | Having a decision support system along the supply chain pipeline will help the upstream and downstream members to provide relevant information |

| Measures | Description |

|---|---|

| Organizational performance (OP) | Refining the accountability, competitiveness, and profitability of manufacturing firms via the enhancement of productivity and non-financial factors |

| Measures | Description |

|---|---|

| Exploitation (EI) | Organizations can be transformed into exploitative elements and can develop repetitive processes to gain efficiency and effectiveness in operations functions |

| Exploration (ER) | Explorative capacity in the operational process will help organizations to discover new knowledge and opportunities to gain further economic development and novel technologies |

| Variable | Item | Loading | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | EI01 | 0.807 | 0.874 | 0.909 | 0.666 |

| EI02 | 0.804 | ||||

| EI03 | 0.793 | ||||

| EI04 | 0.862 | ||||

| EI05 | 0.811 | ||||

| ER | ER01 | 0.799 | 0.858 | 0.898 | 0.638 |

| ER02 | 0.859 | ||||

| ER03 | 0.768 | ||||

| ER04 | 0.775 | ||||

| ER05 | 0.789 | ||||

| OP | OP01 | 0.791 | 0.962 | 0.966 | 0.653 |

| OP02 | 0.844 | ||||

| OP03 | 0.774 | ||||

| OP04 | 0.767 | ||||

| OP05 | 0.786 | ||||

| OP06 | 0.819 | ||||

| OP07 | 0.788 | ||||

| OP08 | 0.830 | ||||

| OP09 | 0.768 | ||||

| OP10 | 0.862 | ||||

| OP11 | 0.814 | ||||

| OP12 | 0.839 | ||||

| OP13 | 0.853 | ||||

| OP14 | 0.816 | ||||

| OP15 | 0.765 | ||||

| PD | PD01 | 0.781 | 0.905 | 0.925 | 0.639 |

| PD02 | 0.857 | ||||

| PD03 | 0.805 | ||||

| PD04 | 0.736 | ||||

| PD05 | 0.820 | ||||

| PD06 | 0.781 | ||||

| PD07 | 0.810 | ||||

| VS | VS01 | 0.745 | 0.912 | 0.928 | 0.619 |

| VS02 | 0.759 | ||||

| VS03 | 0.844 | ||||

| VS04 | 0.841 | ||||

| VS05 | 0.832 | ||||

| VS06 | 0.727 | ||||

| VS07 | 0.759 | ||||

| VS08 | 0.779 |

| Construct | EI | ER | OP | PD | VS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | |||||

| ER | 0.816 | ||||

| OP | 0.785 | 0.701 | |||

| PD | 0.883 | 0.819 | 0.760 | ||

| VS | 0.815 | 0.749 | 0.771 | 0.719 |

| Construct | EI | ER | OP |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIF | VIF | VIF | |

| PD | 2.853 | 2.853 | 3.903 |

| VS | 3.522 | 3.522 | 3.583 |

| EI | 4.112 | ||

| ER | 3.504 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std Beta | Std Error | t-Value | p-Value | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | VS -> OP | 0.125 | 0.060 | 2.093 | 0.018 | 0.030 | 0.230 | Supported |

| H2 | PD -> OP | 0.099 | 0.060 | 1.653 | 0.049 | 0.020 | 0.197 | Supported |

| H3 | VS -> EI | 0.105 | 0.056 | 1.879 | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.208 | Supported |

| H4 | VS -> ER | 0.111 | 0.066 | 1.693 | 0.046 | 0.001 | 0.214 | Supported |

| H5 | PD -> EI | 0.340 | 0.059 | 5.788 | 0.000 | 0.240 | 0.430 | Supported |

| H6 | PD -> ER | 0.534 | 0.053 | 10.039 | 0.000 | 0.453 | 0.624 | Supported |

| H7 | EI -> OP | 0.114 | 0.050 | 2.280 | 0.010 | 0.026 | 0.136 | Supported |

| H8 | ER -> OP | 0.095 | 0.048 | 1.970 | 0.023 | 0.032 | 0.122 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std Beta | Std Error | t-Value | p-Value | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H9 | VS -> EI -> OP | 0.060 | 0.031 | 1.899 | 0.029 | 0.008 | 0.109 | Supported |

| H10 | VS -> ER -> OP | 0.062 | 0.016 | 3.870 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.052 | Supported |

| H11 | PD -> EI -> OP | 0.193 | 0.038 | 5.119 | 0.000 | 0.132 | 0.253 | Supported |

| H12 | PD -> ER -> OP | 0.106 | 0.039 | 2.696 | 0.004 | 0.045 | 0.174 | Supported |

| Construct | EI | ER | OP |

|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 0.003 | ||

| ER | 0.002 | ||

| PD | 0.151 | 0.317 | 0.009 |

| VS | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pertheban, T.R.; Thurasamy, R.; Marimuthu, A.; Venkatachalam, K.R.; Annamalah, S.; Paraman, P.; Hoo, W.C. The Impact of Proactive Resilience Strategies on Organizational Performance: Role of Ambidextrous and Dynamic Capabilities of SMEs in Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612665

Pertheban TR, Thurasamy R, Marimuthu A, Venkatachalam KR, Annamalah S, Paraman P, Hoo WC. The Impact of Proactive Resilience Strategies on Organizational Performance: Role of Ambidextrous and Dynamic Capabilities of SMEs in Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612665

Chicago/Turabian StylePertheban, Thillai Raja, Ramayah Thurasamy, Anbalagan Marimuthu, Kumara Rajah Venkatachalam, Sanmugam Annamalah, Pradeep Paraman, and Wong Chee Hoo. 2023. "The Impact of Proactive Resilience Strategies on Organizational Performance: Role of Ambidextrous and Dynamic Capabilities of SMEs in Manufacturing Sector" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612665

APA StylePertheban, T. R., Thurasamy, R., Marimuthu, A., Venkatachalam, K. R., Annamalah, S., Paraman, P., & Hoo, W. C. (2023). The Impact of Proactive Resilience Strategies on Organizational Performance: Role of Ambidextrous and Dynamic Capabilities of SMEs in Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability, 15(16), 12665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612665