Increasing Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for the Sustainability of Live Farming Assistance: A Group Impact Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

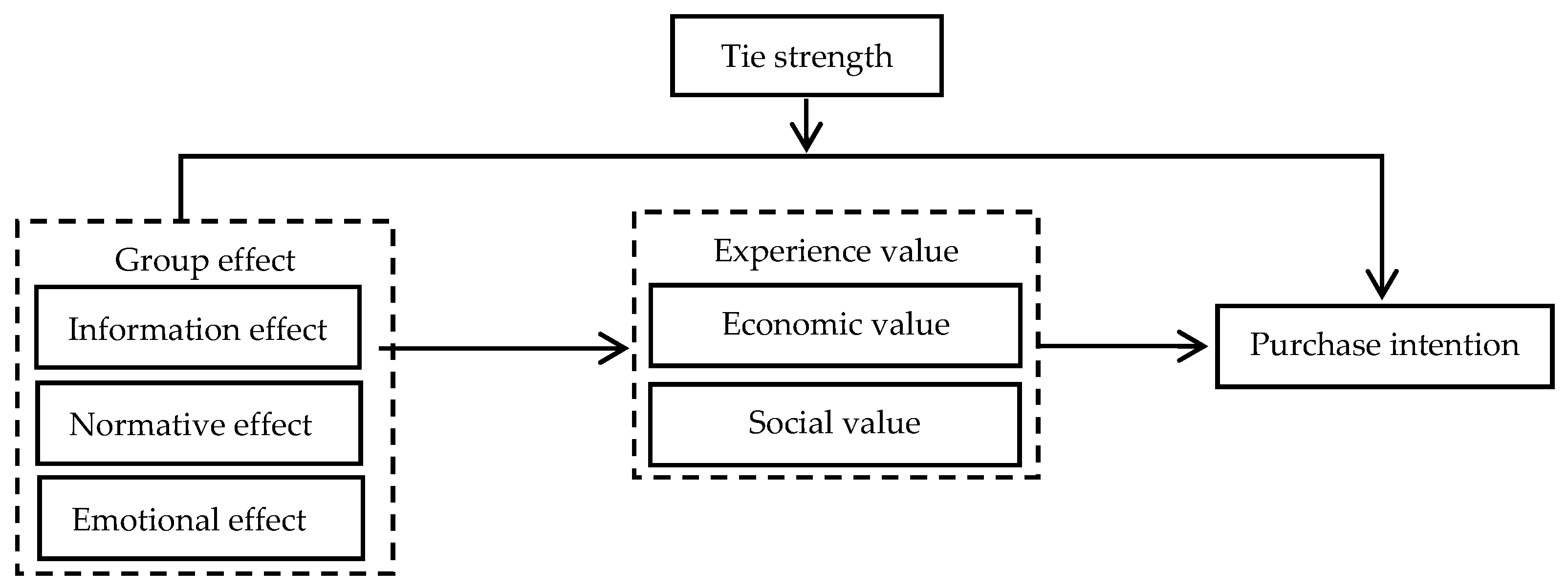

2. Overview of Studies and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Live Farming Assistance

2.2. Group Effect in Live Farming Assistance

2.3. Experience Value

2.4. The Influence of Group Effect on Purchase Intention

2.5. The Mediating Role of Experience Value

2.6. The Moderating Role of Tie Strength

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Measurement

3.2. Pre-Investigation and Questionnaire Revision

3.3. Formal Survey and Sample Description

3.4. Analytical Approach

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

4.2. Common Method Variance Test

4.3. Hypothesis Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Research Enlightenment

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, H.D.; Qu, J. A study on the sustainability of direct broadcasting with goods to help farmers. People’s Trib. 2020, 20, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.X.; Zhao, X.F. Live farming assistance: A new model of rural e-commerce for the integrated development of rural revitalization and network poverty alleviation. J. Commer. Econ. 2020, 19, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.P.; Luo, W.P. The key path to enhance user stickiness in the context of agricultural live broadcasting. China Bus. Mark. 2022, 36, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. The Effects of Match-ups on the Consumer Attitudes toward Internet Celebrities and Their Live Streaming Contents in the Context of Product Endorsement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K. The Influence of Perceived Trust and Time Moderator on the Purchase Intention of Consumers in the Context of E-Commerce Livestreaming. In Proceedings of the WHICEB 2021 Proceedings, Wuhan, China, 5–7 August 2021; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/whiceb2021/53 (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Xue, J. What and how driving consumer engagement and purchase intention in officer live streaming? A two-factor theory perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 56, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Q. What Drives Consumer Shopping Behavior in Live Streaming Commerce? J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 21, 144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Liu, L.C.; Liu, C.L. Impulsive Purchase Intention of Live Streaming E-commerce Consumers from the Perspective of Emotion. China Bus. Mark. 2022, 36, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.J.; Liu, Q. Bullet Screen Interaction, Online Commodity Display and Consumers’ Impulsive Purchasing Behavior-mediated by Presence and Flow Experience. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 3, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, M.; Tan, H.; Peng, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L. Promoting or Attenuating? An Eye-tracking Study on the Role of Social Cues in E-commerce Livestreaming. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 142, 113466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Qin, F.; Wang, G.A. E-service quality on live streaming platforms: Swift guanxi perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 35, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Jiang, X. Understanding Consumer Impulse Buying in Livestreaming Commerce: The Product Involvement Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, B. How is the Purchase Intention of Consumers Affected in the Environment of E-commerce Live Streaming? In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Financial Management and Economic Transition (FMET 2021), Guangzhou, China, 27–29 August 2021; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.; Yuan, L.Y.; Xie, L.H. Empirical Evidence of Purchase Behavior Mechanism of Live-streaming Bandwagon Users Based on ABC Attitude Theory. Soft Sci. 2022, 12, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The Influence of Source Credibility on Communication Effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, X.T. How Live Streaming Influences Purchase Intentions in Social Commerce: An IT Affordance Perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 37, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cheah, J.-H.; Liu, Y. To Stream or not to Stream? Exploring Factors Influencing Impulsive Consumption through Gastronomy Livestreaming. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3394–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.W.; Ma, C.J.; Li, L.L. Livestreaming E-commerce and Agricultural Product upward Value Reconstruction: Mechanism and Realization Path. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 2, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zhu, C.X.; Zhu, H.B. Formation Mechanism of Consumer Trust in Livestreaming of Agricultural E-commerce: From the Perspective of Intermediary Capability. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 21, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.Z.; Hou, Y.X.; Ge, R. Analysis on Characteristics of Online Shopping Agricultural Products in China. Issues Agric. Econ. 2012, 33, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.Y.; Xu, Z.L. The influence of e-commerce anchor attributes on consumers’ willingness to purchase online—A study based on the rooting theory approach. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2020, 10, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.W.; Hou, M.L.; Zhou, L. An investigation of the impact of social e-commerce interaction styles on consumer advertising attitudes. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.H.; Zhu, R.N. Convergent Communication and Interactive Ceremony: CCTV news Live with Goods Mode Exploration. TV Res. 2020, 10, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden, W.O.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Teel, J.E. Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 15, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional Contagion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 2, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Etzel, M.J. Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decision. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y. Practical Path and Value Analysis of Public Welfare Livestreaming to Help Farmers—A Case Study of Three Central Media Cooperating with Taobao Livestreaming to Bring Goods for Public Welfare. Media 2021, 5, 37–38+40. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.; Liu, C.L.; Shi, K.; Liu, J.Z. A Study of Emotional Infection Pathways Influencing Online Collective Behavioral Intentions-Based on an Emotion-Information Theoretical Perspective. J. Intell. 2018, 37, 103–109+121. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B. Introduction to Consumer Value, Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1999; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential Value: Conceptualization, Measurement and Application in the Catalog and Internet Shopping Environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumption Experience, Customer Value, and Subjective Personal Introspection: An Illustrative Photographic Essay. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebnitz, N.; Grunert, K.G. The Impact of Abnormally Shaped Vegetables on Consumers’ Risk Perception. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenbusch, S.; Zettler, I.; Voss, T.; Lösch, T.; Trautwein, U. Exploring reference group effects on teachers’ nominations of gifted students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Lee, K.C. Investigating the Moderating Role of Uncertainty Avoidance Cultural Values on Multidimensional Online Trust. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood, Misattribution, and Judgments of Well-being: Informative and Directive Functions of Affective States. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.H. Experiential Value Affects Purchase Intentions for Online-to-offline Goods: Consumer Feedback as a Mediator. J. Mark. Manag. 2018, 6, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.H.C.; Oh, J.; Scheinbaum, A.C. Interactive Music for Multisensory E-commerce: The Moderating Role of Online Consumer Involvement in Experiential Value, Cognitive Value, and Purchase Intention. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 1031–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaar, P.E.; Janssen, L.; Vergeer, M.; van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Crutzen, R.; van’t Riet, J. The success of viral ads: Social and attitudinal predictors of consumer pass-on behavior on social network sites. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2603–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E. Social Network Ties beyond Nonredundancy: An Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Knowledge Content and Tie Strength on Creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R. Consumer Behavior, Buying, Having, and Being; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, M.H. Study on the factors influencing the purchase of agricultural products in the consumer online channel. Rural Econ. 2019, 10, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Mu, J.; Song, L. Research on the factors influencing consumers’ willingness to purchase fresh produce online—An empirical analysis based on the UTAUT model. Dongyue Trib. 2018, 4, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, F.Y.; Chen, W.P. The effects of technology availability and anchor characteristics on consumers’ willingness to purchase agricultural products. Rural Econ. 2021, 11, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, R.W.; Orimoto, L.; Singelis, T.M.; Hatfield, E.; Hebb, J. Emotional contagion: Gender and occupational differences. Psychol. Women Q. 1995, 19, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T.; Kanto, A.; Kuusela, H.; Spence, M.T. Decomposing the value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions: Evidence from Finland. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.S.; Voyer, P.A. Word-of-mouth Processes within a Services Purchase Decision Context. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.J.; Meng, L.; Chen, S.Y.; Duan, K. A study on the influence of Netflix live streaming on consumers’ purchase intention and its mechanism. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.S.; Tang, S.H.; Xiao, J. A study of consumers’ purchase intention on live e-commerce platform—Based on social presence perspective. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2021, 1, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.F.; Gao, Q.A. Research on the factors influencing the willingness to purchase agricultural products online and the mechanism of their effect—Analysis based on the perspective of reference effect. J. Beijing Technol. Bus. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2016, 3, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.Q. Influence of Netflix Traits on Fans’ Purchase Intentions in Live Streaming Platforms. China Bus. Mark. 2020, 10, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.X.; Ye, Z.L.; Wu, Y.P.; Liu, J.Y. Study on the mechanism of influence of live scene atmosphere cues on consumers’ intention to consume impulsively. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 6, 875–882. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.M.; Duan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lü, K.; Chen, S. The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming E-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, M.Y.; Wang, Z.B. Live agricultural e-commerce: A new model of e-commerce to alleviate poverty. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 11, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self–efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Variables | Classify | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 44.70% |

| Woman | 55.30% | |

| Monthly income | CNY 5000 and below | 16.50% |

| CNY 501–10,000 | 30.70% | |

| CNY 10,001–15,000 | 26.10% | |

| CNY 1001–20,000 | 14.10% | |

| More than CNY 2000 | 12.60% | |

| Shopping frequency of live farming assistance | Less | 11.60% |

| 3–4 times a year | 35.90% | |

| 3–4 times a month | 31.00% | |

| 3–4 times a week | 13.40% | |

| More | 8.10% | |

| Age | Under 18 years old | 3.50% |

| 18–26 years old | 12.70% | |

| 27–39 years old | 50.00% | |

| 40–49 years old | 20.70% | |

| 50–59 years old | 8.10% | |

| 60 years old and above | 5.00% | |

| Live online shopping experience | Less than 1 year (inclusive) | 12.70% |

| 1–2 years (excluding 2 years) | 28.90% | |

| 2–3 years (excluding 3 years) | 21.90% | |

| 3–4 years (excluding 4 years) | 15.10% | |

| 4–5 years (excluding 5 years) | 14.20% | |

| More than 5 years (inclusive) | 7.20% |

| Variable | Measurement Item | Standardized Load | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informational effect a = 0.878 | If I’m not familiar with a certain product, I’ll ask for information about the product in the live farming assistance. | 0.792 | 0.646 | 0.879 |

| When I want to buy the best product from similar products, I will ask in the live farming assistance. | 0.835 | |||

| Before buying the product, I will learn about all aspects of the product in the live farming assistance. | 0.825 | |||

| In order to ensure that I can buy the products I want, I will observe what the people in the live farming assistance have bought. | 0.760 | |||

| Normative effect a = 0.932 | People in the live farming assistance can see whether I make a purchase or not through the screen, so I will buy the product. | 0.879 | 0.669 | 0.934 |

| It’s important for me that people in the live farming assistance like me to buy products in the live farming assistance. | 0.866 | |||

| People in the live farming assistance recognize the purchase of agricultural products, so I will buy products in the live farming assistance. | 0.831 | |||

| I want to know if others have a good impression of the people who buy products in the live farming assistance. | 0.784 | |||

| I want to get a sense of belonging by buying products in the live farming assistance like the people in the live farming assistance. | 0.754 | |||

| If I want to be the same person as the people in the live farming assistance room, I will try to buy agricultural products through live farming assistance. | 0.795 | |||

| I want to identify myself with others by purchasing products in the live farming assistance. | 0.807 | |||

| Emotional effect a = 0.936 | When the anchor smiles warmly at me, I will smile back and feel warm inside. | 0.867 | 0.746 | 0.936 |

| When I am in the live farming assistance in a cheerful atmosphere, my heart will be filled with happiness. | 0.845 | |||

| I also feel sad when the anchor talks about the tragic experience of farmers. | 0.871 | |||

| If the anchor cries, I’ll have tears in my eyes. | 0.871 | |||

| I can very sensitively capture the emotional changes of the anchor and other audiences. | 0.864 | |||

| Economic value a = 0.907 | It can save some money to buy agricultural products in the live farming assistance. | 0.802 | 0.623 | 0.908 |

| I can buy cheap agricultural products in the live farming assistance. | 0.803 | |||

| The agricultural products in the live farming assistance are cheaper than those in other places. | 0.686 | |||

| I can buy the agricultural products I need in the live farming assistance. | 0.827 | |||

| There will be no chaotic queues or other delays in the live farming assistance. | 0.779 | |||

| It is very convenient to buy agricultural products in the live farming assistance room. | 0.828 | |||

| Social value a = 0.926 | Live farming assistance makes me feel that I will be accepted. | 0.876 | 0.758 | 0.926 |

| Live farming assistance will improve others’ perception of me. | 0.886 | |||

| Live farming assistance will help me make a good impression on others. | 0.873 | |||

| Live farming assistance will make me recognized by the society. | 0.847 | |||

| Purchase intention a = 0.873 | I am willing to buy agricultural products in the live farming assistance. | 0.860 | 0.702 | 0.876 |

| I have a good chance to buy agricultural products in the live farming assistance. | 0.858 | |||

| I will recommend the live farming assistance to others. | 0.794 | |||

| Tie strength a = 0.900 | I have a close connection with the people in the live farming assistance. | 0.828 | 0.696 | 0.901 |

| I may share my secret with the people in the live farming assistance. | 0.847 | |||

| I may provide daily help to the people in the live farming assistance. | 0.812 | |||

| It’s possible for me to spend my free time with the people in the live farming assistance. | 0.849 |

| Variable | Informational Effect | Normative Effect | Emotional Effect | Economic Value | Social Value | Purchase Intention | Tie Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informational effect | 0.804 | ||||||

| Normative effect | 0.574 *** | 0.818 | |||||

| Emotional effect | 0.642 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.864 | ||||

| Economic value | 0.641 *** | 0.651 *** | 0.562 *** | 0.789 | |||

| Social value | 0.493 *** | 0.699 *** | 0.489 *** | 0.664 *** | 0.871 | ||

| Purchase intention | 0.705 *** | 0.601 *** | 0.632 *** | 0.663 *** | 0.556 *** | 0.838 | |

| Tie strength | 0.393 *** | 0.650 *** | 0.411 *** | 0.596 *** | 0.679 *** | 0.433 *** | 0.834 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic value | ← | Informational effect | 0.326 *** | 0.049 | 6.944 |

| Social value | ← | Informational effect | 0.091 * | 0.057 | 2.003 |

| Economic value | ← | Normative effect | 0.398 *** | 0.038 | 9.667 |

| Social value | ← | Normative effect | 0.593 *** | 0.049 | 13.656 |

| Economic value | ← | Emotional effect | 0.141 *** | 0.036 | 3.344 |

| Social value | ← | Emotional effect | 0.114 ** | 0.043 | 2.702 |

| Purchase intention | ← | Informational effect | 0.344 *** | 0.052 | 6.967 |

| Purchase intention | ← | Normative effect | 0.109 * | 0.049 | 2.125 |

| Purchase intention | ← | Emotional effect | 0.199 *** | 0.036 | 4.738 |

| Purchase intention | ← | Economic value | 0.210 *** | 0.048 | 4.442 |

| Purchase intention | ← | Social value | 0.076 + | 0.038 | 1.708 |

| Variable | Purchase Intention | Economic Value | Social Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | |

| Gender | −0.031 | −0.017 | −0.022 | −0.015 | −0.013 | −0.021 | −0.019 | −0.026 | 0.024 | −0.011 |

| Age | −0.121 ** | −0.058 * | −0.070 ** | −0.065 * | −0.070 * | −0.065 * | −0.068 * | −0.073 ** | 0.051 | 0.041 |

| Monthly income | −0.120 ** | −0.033 | −0.028 | −0.043 | −0.034 | −0.032 | −0.031 | −0.028 | −0.02 | 0.060 * |

| Shopping frequency of live farming assistance | 0.088 * | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.053 |

| Live online shopping experience | 0.100 ** | 0.105 *** | 0.094 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.108 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.110 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.051 | 0.040 |

| Informational effect | 0.337 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.322 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.300 *** | 0.325 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.098 ** | |

| Normative effect | 0.238 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.154 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.379 *** | 0.521 *** | |

| Emotional effect | 0.245 *** | 0.211 *** | 0.222 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.211 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.157 *** | 0.144 *** | |

| Economic value | 0.218 *** | |||||||||

| Social value | 0.159 *** | |||||||||

| Tie strength | 0.082 * | 0.083 * | 0.079 * | 0.068 * | ||||||

| Informational effect × Tie strength | −0.115 *** | |||||||||

| Normative effect × Tie strength | −0.106 *** | |||||||||

| Emotional effect × Tie strength | −0.190 *** | |||||||||

| R2 | 0.048 | 0.503 | 0.528 | 0.516 | 0.506 | 0.516 | 0.515 | 0.534 | 0.474 | 0.463 |

| ΔR2 | 0.048 | 0.455 | 0.480 | 0.468 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.028 | 0.450 | 0.425 |

| ∆F | 7.136 *** | 215.476 *** | 179.327 *** | 170.851 *** | 5.547 * | 14.243 *** | 12.583 *** | 41.758 *** | 201.681 *** | 186.300 *** |

| Number | Hypothesis | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | The informational effect has a positive impact on consumer purchase intention. | Supported |

| H1b | The normative effect has a positive impact on consumer purchase intention. | Supported |

| H1c | The emotional effect has a positive impact on consumer purchase intention. | Supported |

| H2a | Economic value mediates the relationship between group effect and consumer purchase intention. | Supported |

| H2b | Social value mediates the relationship between group effect and consumer purchase intention. | Supported |

| H3a | Tie strength moderates the relationship between informational influence and purchase intention, such that this relationship is stronger when tie strength is low as opposed to high. | Supported |

| H3b | Tie strength moderates the relationship between normative influence and purchase intention, such that this relationship is stronger when tie strength is low as opposed to high. | Supported |

| H3c | Tie strength moderates the relationship between emotional influence and purchase intention, such that this relationship is stronger when tie strength is low as opposed to high. | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, G.; Chang, L.; Zhang, G. Increasing Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for the Sustainability of Live Farming Assistance: A Group Impact Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712741

Li G, Chang L, Zhang G. Increasing Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for the Sustainability of Live Farming Assistance: A Group Impact Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712741

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Guangming, Liting Chang, and Guiqing Zhang. 2023. "Increasing Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for the Sustainability of Live Farming Assistance: A Group Impact Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712741

APA StyleLi, G., Chang, L., & Zhang, G. (2023). Increasing Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for the Sustainability of Live Farming Assistance: A Group Impact Perspective. Sustainability, 15(17), 12741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712741