Privacy Concerns in Social Commerce: The Impact of Gender

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1: Do differences in attitude towards online privacy, between men and women, in Saudi Arabia, impact the intention to use s-commerce?

- RQ2: To what extent do these differences, if they exist, impact reported behaviour, in terms of engaging with s-commerce?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Commerce

2.2. S-Commerce and Privacy

2.3. Gender and Attitudes to Privacy

3. Research Method

4. Exploratory Stage

4.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

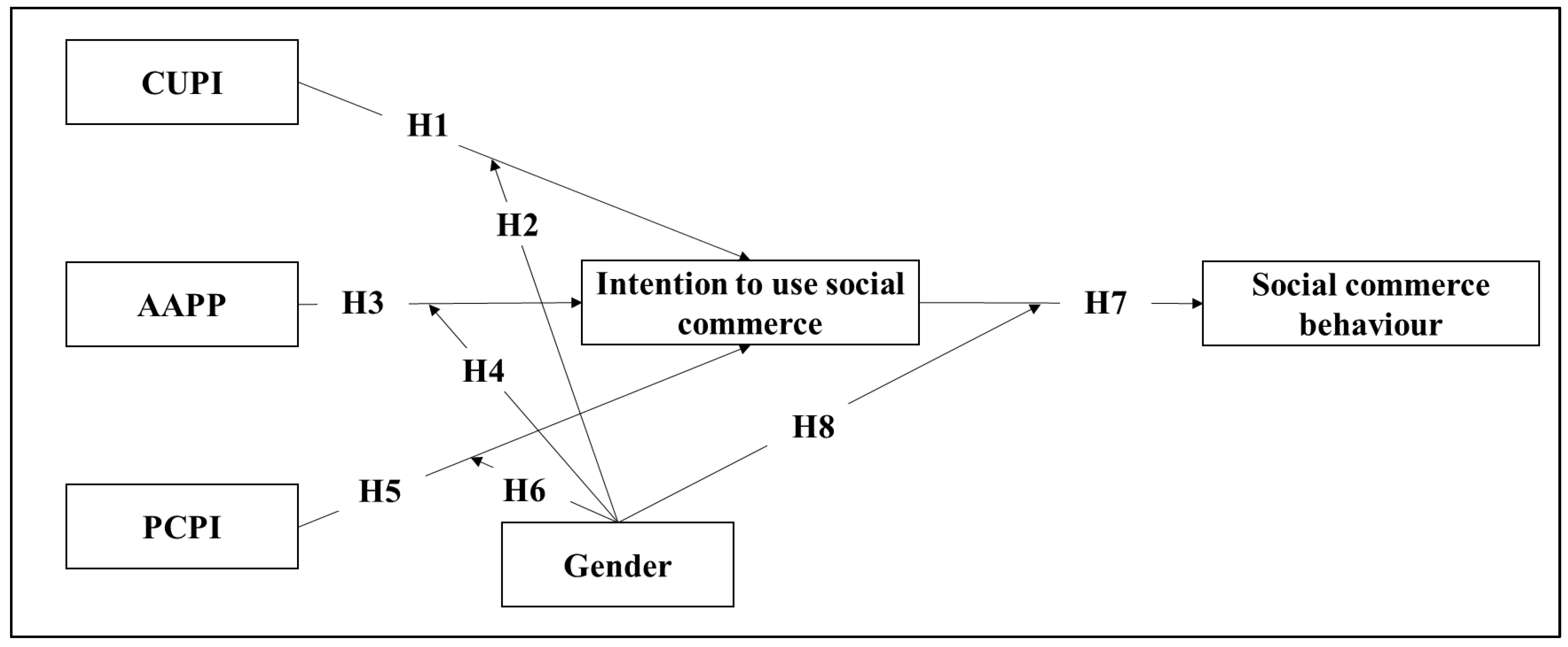

4.2. Findings of the Exploratory Stage and Hypothesis Development

- AAPP—a measure of users’ belief in the relevance and effectiveness of privacy policies (specific to the platform) in protecting and safeguarding private data.

- CUPI—a measure of the level of user concern that the service provider will abuse private data.

- PCPI—a measure of a user’s confidence that they are in control of any private information provided to the service provider.

4.2.1. Collection and Use of Personal Information (CUPI)

Most things in life involve a risk reward equation. The same is true with s-commerce. In order to take advantage of s-commerce, you have to share some private information, but the risks of this being abused are relatively small compared with the rewards on offer.

This is a highly connected, digital world which can offer many benefits. The cost is that you have to make some private information publicly available in order to engage with it. It’s true that this information could be abused, but it’s a risk we have to take. Having said that, it’s always worth looking at the privacy policies of the app you are using, to check that the risks are minimised.

The amount of information you need to supply seems totally unnecessary for the services provided. What’s worse is that once you’ve given up this information, you usually have no control over it, and it could be abused in lots of ways. And what does one do when there is a misuse of one’s data? I find the whole situation very worrying.

Stories of how private information has been abused are all around us. It’s scary. Although I do quite a lot of s-commerce, it took me quite a while to gain the confidence to do so, and —even now —I’m forever worrying about what could happen if my private information falls into the wrong hands.

The problem is that you have very little say over how your information is used. The privacy policies they publish are usually impenetrable legal jargon, so you have no idea whether you’re protected or not—and if your data is abused what action can you take? These social media companies normally hold all the power.

4.2.2. Awareness and Acceptance of Privacy Policy (AAPP)

I’m aware that all the big platforms publish extensive privacy policies, but, to be honest, I rarely engage with such policies these days. They’re usually written to cover the service providers back, not the users, and it’s often difficult to make sense of them.

The length and technical nature of a typical privacy policy makes them pretty well inaccessible to most users. I think that this is probably true with all online platforms, not just social media and s-commerce.

I know I should read them, but I don’t actually do so very often. As far as I can tell, they are a cut and paste exercise from other companies, so when you’ve read one you’ve read them all. However, it worries me if a service provider doesn’t actually have a privacy policy.

They’re usually hard to understand, and they’re long and tedious, but it’s worth making the effort to read them, to make sure that your private stuff is protected at least to some degree. Everyone knows what can happen if your private information gets into the wrong hands.

Privacy policies are important, but in my experience they tend to be very generic and usually built to fit the laws of Western countries, so don’t take account of regional cultural or religious needs. All the same, I do always scan the relevant policy before signing up to a platform or app, especially in s-commerce, which can expose you to more risk than some other activities.

I like to know where I stand when it comes to privacy and sharing information, so I nearly always have a brief look at the privacy policy. I wouldn’t be very confident that these policies actually prevent abuse, though. The big companies know that most users either don’t understand them, or are too involved in their [s-commerce] activities to care.

4.2.3. Perceived Control of Private Information (PCPI)

As users usually have little or no control over what happens to the data they share, then that information is vulnerable to abuse. This means that users should only share the minimum amount of information that’s required by the platform, in order to mitigate risks.

Given that you can’t control what happens to the information that you supply, it makes sense to share it only If you have to. I tend to feel more confident about platforms that give the user some level of ability to edit and control private account information through a settings panel—the implication is that these platforms care more about data security and privacy than platforms which don’t give this facility.

Most s-commerce platforms allow users some control over the amount of information they provide, but they often give very little guidance or advice on how to use things like filters and passwords effectively. This leaves many users thinking they have less control than they really do.

There’s not much point in expecting governments or tech companies to provide high levels of data protection, so users need to become more tech savvy.

4.2.4. The Effect of Attitude and Intention Behaviour

5. Confirmatory Stage

5.1. Developing the Research Questionnaire

5.2. Content Validity Assessment

5.3. Primary Data Collection

- -

- Respondents were provided with clear and concise instructions about the purpose of the survey and how to complete it—this included information about how to answer each question and how to complete the questionnaire within the given time frame.

- -

- Clear and concise language was used in developing the research questionnaire (see Section 5.1 for more details).

- -

- Respondents were given an option to email or call the researchers to clarify any ambiguous responses or ask additional questions.

- -

- Before administering the questionnaire to the target population, a pilot study was performed (see Section 5.1 for more details).

5.4. Descriptive Statistics and Normality Testing

5.5. Data Analysis Techniques

5.6. Testing the Measurement Model

5.7. Results of Structural Model Evaluation

5.8. Gender Differentials Based on the Model—Analysis of the Model Paths

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications for Research and Theory

6.2. Managerial Implications

- Social commerce managers should focus on enhancing both Perceived Control of Private Information (PCPI) and the perceived benefits of social commerce in order to increase women’s engagement. They should also consider the unique privacy concerns of women when designing their platforms and marketing campaigns.

- Awareness and Acceptance of Privacy Policy (AAPP) is an important factor in user engagement, as users who are aware of and accept the privacy policy of a platform are more likely to engage with that platform. AAPP can be influenced by a number of factors, including the clarity of the privacy policy, the perceived trustworthiness of the platform and the user’s own privacy concerns [5]. Gender is one of the factors that can influence AAPP, with women being more likely than men to be concerned about their privacy and less likely to accept privacy policies that they do not understand or trust [99,100]. Platforms should take gender into account when developing their privacy policies and marketing campaigns. They should make sure that their privacy policies are clear and concise, and that they address the specific privacy concerns of women. They should also build trust with women by being transparent about how their data are collected and used.

- Managers should consider the target audience, the regulatory environment and the technological landscape when developing their privacy policies and marketing campaigns. The privacy concerns of different users may vary depending on their age, gender and location. Managers should tailor their privacy policies and marketing campaigns to the specific needs of their target audience.

- Collection and Use of Personal Information (CUPI) is an important factor in user engagement, as users who are concerned about how their data will be used and shared are less likely to engage with a platform [8,24,38] unless they are effectively reassured that the platform protects their data. The effect of CUPI can be influenced by a number of factors, including the perceived trustworthiness of the platform, the user’s own privacy concerns and the platform’s privacy practices [101,102]. Platforms can address the appropriate scepticism inherent in CUPI by being transparent about how they collect and use data, by building trust with users and by taking steps to protect user privacy. Gender can play a role in CUPI, as different genders may have different privacy concerns. For example, a study by Mutambik et al. [38] found that women are more likely than men to be concerned about their personal information being used for marketing purposes. They are also more likely to be concerned about their personal information being used to track their online activity.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Value of Social Commerce Sales Worldwide from 2022 to 2026. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1251145/social-commerce-sales-worldwide/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Statista. Leading Factors that Would Drive Online Shoppers Worldwide to Increase Their Use of Social Commerce in 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1275069/leading-drivers-social-commerce-use-increase/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Liang, T.-P.; Ho, Y.-T.; Li, Y.-W.; Turban, E. What Drives Social Commerce: The Role of Social Support and Relationship Quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Most Popular Social Commerce Platforms among Digital Buyers in the United States in 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/250909/brand-engagement-of-us-online-shoppers-on-pinterest-and-facebook/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Mutambik, I.; Lee, J.; Almuqrin, A.; Zhang, J.Z.; Homadi, A. The Growth of Social Commerce: How It Is Affected by Users’ Privacy Concerns. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Guo, H.; You, X.; Xu, L. Privacy Rating of Mobile Applications Based on Crowdsourcing and Machine Learning. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. International Mobile Marketing: A Satisfactory Concept for Companies and Users in Times of Pandemic. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 1826–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I.; Almuqrin, A.; Liu, Y.; Alhossayin, M.; Qintash, F.H. Gender Differentials on Information Sharing and Privacy Concerns on Social Networking Sites: Perspectives From Users. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Forecast Number of Mobile Devices Worldwide from 2020 to 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/245501/multiple-mobile-device-ownership-worldwide/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J.; Zadeh, A.H.; Richard, M.-O. A Social Commerce Investigation of the Role of Trust in a Social Networking Site on Purchase Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N. The Impact of Positive Valence and Negative Valence on Social Commerce Purchase Intention. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 33, 774–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wong, S.F.; Libaque-Saenz, C.F.; Lee, H. The Role of Privacy Policy on Consumers’ Perceived Privacy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, C.; Bijmolt, T.H.A.; Maestripieri, S.; Luceri, B. Drivers of Consumer Adoption of E-Commerce: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2022, 39, 1186–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Alyatama, S.; Al Khattab, A.; Alsoboa, S.S.; Almaiah, M.A.; Ramadan, M.H.; Arafa, H.M.; Ahmed, N.A.; Alsyouf, A.; et al. Assessing Customers Perception of Online Shopping Risks: A Structural Equation Modeling–Based Multigroup Analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Everard, A. User Attitude Towards Instant Messaging: The Effect of Espoused National Cultural Values on Awareness and Privacy. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2008, 11, 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorska, A.; Korzynski, P.; Mazurek, G.; Pucciarelli, F. The Role of Social Media in Scholarly Collaboration: An Enabler of International Research Team’s Activation? J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 23, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, U.; Yadav, S.K.; Kumar, Y. Understanding Research Online Purchase Offline (ROPO) Behaviour of Indian Consumers. Int. J. Online Mark. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutimukwe, C.; Kolkowska, E.; Grönlund, Å. Information Privacy in E-Service: Effect of Organizational Privacy Assurances on Individual Privacy Concerns, Perceptions, Trust and Self-Disclosure Behavior. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilcec, R.F.; Viberg, O.; Jivet, I.; Martinez Mones, A.; Oh, A.; Hrastinski, S.; Mutimukwe, C.; Scheffel, M. The Role of Gender in Students’ Privacy Concerns about Learning Analytics. In Proceedings of the LAK23: 13th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, Arlington, TX, USA, 13–17 March 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Herrando, C. Does Privacy Assurance on Social Commerce Sites Matter to Millennials? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; El-Gayar, O. The Effect of Privacy Policies on Information Sharing Behavior on Social Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, W.; Maayan, Z.G.; Dan, B. Sex Differences in Attitudes towards Online Privacy and Anonymity among Israeli Students with Different Technical Backgrounds. arXiv 2017, arXiv:2308.03814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, M.G.; Milne, G. Gender Differences in Privacy-Related Measures for Young Adult Facebook Users. J. Interact. Advert. 2010, 10, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifferet, S. Gender Differences in Privacy Tendencies on Social Network Sites: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, M.; Dehlinger, J. Observed Gender Differences in Privacy Concerns and Behaviors of Mobile Device End Users. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 37, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørum, H.; Eg, R.; Presthus, W. A Gender Perspective on GDPR and Information Privacy. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 196, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatori, L.; Marcantoni, F. Social Commerce: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2015 Science and Information Conference (SAI), London, UK, 28–30 July 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. Browsing and Shopping Directly on Social Media Platforms Is a Core Feature of E-Commerce in China. Now, This Dynamic New Way of Buying Is Poised for Rapid Growth in the United States. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/social-commerce-the-future-of-how-consumers-interact-with-brands (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Ziyadin, S.; Doszhan, R.; Borodin, A.; Omarova, A.; Ilyas, A. The Role of Social Media Marketing in Consumer Behaviour. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 135, 04022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S. Emotional Attachment in Social E-Commerce: The Role of Social Capital and Peer Influence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Ho, D. Online Privacy Concerns and Privacy Protection Strategies among Older Adults in East York, Canada. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 71, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruikemeier, S.; Boerman, S.C.; Bol, N. Breaching the Contract? Using Social Contract Theory to Explain Individuals’ Online Behavior to Safeguard Privacy. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, S.; Ionita, D.; Hartel, P. Understanding Online Privacy—A Systematic Review of Privacy Visualizations and Privacy by Design Guidelines. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xiang, D.; He, J. Data Privacy Protection in News Crowdfunding in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qirim, N.; Rouibah, K.; Abbas, H.; Hwang, Y. Factors Affecting the Success of Social Commerce in Kuwaiti Microbusinesses: A Qualitative Study. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, N.; Gerber, P.; Volkamer, M. Explaining the Privacy Paradox: A Systematic Review of Literature Investigating Privacy Attitude and Behavior. Comput. Secur. 2018, 77, 226–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chu, J.; Zheng, L.J. Better Not Let Me Know: Consumer Response to Reported Misuse of Personal Data in Privacy Regulation. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I.; Lee, J.; Almuqrin, A.; Halboob, W.; Omar, T.; Floos, A. User Concerns Regarding Information Sharing on Social Networking Sites: The User’s Perspective in the Context of National Culture. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Speier, C.; Morris, M.G. User Acceptance Enablers in Individual Decision Making About Technology: Toward an Integrated Model. Decis. Sci. 2002, 33, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, N.; Rita, P. Privacy Concerns and Online Purchasing Behaviour: Towards an Integrated Model. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 22, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Hu, H.-H.; Wang, L.; Qin, J.-Q. Privacy Assurances and Social Sharing in Social Commerce: The Mediating Role of Threat-Coping Appraisals. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. The Effect of Information Privacy Concern on Users’ Social Shopping Intention. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M.J.; Bies, R.J. Consumer Privacy: Balancing Economic and Justice Considerations. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meso, P.; Negash, S.; Musa, P.F. Interactions Between Culture, Regulatory Structure, and Information Privacy Across Countries. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libaque-Sáenz, C.F.; Wong, S.F.; Chang, Y.; Bravo, E.R. The Effect of Fair Information Practices and Data Collection Methods on Privacy-Related Behaviors: A Study of Mobile Apps. Inf. Manag. 2020, 58, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.; Gruzd, A.; Hernández-García, Á. Social Media Marketing: Who Is Watching the Watchers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozani, M.; Ayaburi, E.; Ko, M.; Choo, K.-K.R. Privacy Concerns and Benefits of Engagement with Social Media-Enabled Apps: A Privacy Calculus Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Milberg, S.J.; Burke, S.J. Information Privacy: Measuring Individuals’ Concerns about Organizational Practices. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet Users’ Information Privacy Concerns (IUIPC): The Construct, the Scale, and a Causal Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, J.; Nehmad, E. Internet Social Network Communities: Risk Taking, Trust, and Privacy Concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, W. Teens’ Concern for Privacy When Using Social Networking Sites: An Analysis of Socialization Agents and Relationships with Privacy-Protecting Behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqrin, A.; Mutambik, I. The Explanatory Power of Social Cognitive Theory in Determining Knowledge Sharing among Saudi Faculty. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biselli, T.; Steinbrink, E.; Herbert, F.; Schmidbauer-Wolf, G.M.; Reuter, C. On the Challenges of Developing a Concise Questionnaire to Identify Privacy Personas. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2022, 2022, 645–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zahedi, F.M. Individuals’ Internet Security Perceptions and Behaviors: Polycontextual Contrasts Between the United States and China. MIS Q. 2016, 40, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, H.; He, W.; Wang, F.-K.; Jiao, S. A Meta-Analysis to Explore Privacy Cognition and Information Disclosure of Internet Users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Dinev, T.; Xu, H. Information Privacy Research: An Interdisciplinary Review. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 989–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, N.; Dietz, G. Trust Repair After An Organization-Level Failure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaburi, E.W.; Treku, D.N. Effect of Penitence on Social Media Trust and Privacy Concerns: The Case of Facebook. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S. Determinants of Online Privacy Concern and Its Influence on Privacy Protection Behaviors Among Young Adolescents. J. Consum. Aff. 2009, 43, 389–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kumar, S.; Hu, C. Gender Differences in Motivations for Identity Reconstruction on Social Network Sites. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisilevich, S.; Ang, C.S.; Last, M. Large-Scale Analysis of Self-Disclosure Patterns among Online Social Networks Users: A Russian Context. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2012, 32, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamati, J.H.; Ozdemir, Z.D.; Smith, H.J. Information Privacy, Cultural Values, and Regulatory Preferences. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwahk, K.-Y.; Park, D.-H. The Effects of Network Sharing on Knowledge-Sharing Activities and Job Performance in Enterprise Social Media Environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Z. Can You See Me Now? Audience and Disclosure Regulation in Online Social Network Sites. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2008, 28, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Spiekermann, S.; Koroleva, K.; Hildebrand, T. Online Social Networks: Why We Disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Brooks, S. Factors Affecting Online Consumer’s Behavior: An Investigation Across Gender. In Proceedings of the 19th Americas Conference on Information Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–17 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almuqrin, A.; Zhang, Z.; Alzamil, A.; Mutambik, I.; Alhabeeb, A. The Explanatory Power of Social Capital in Determining Knowledge Sharing in Higher Education: A Case from Saudi Arabia. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 25, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Califf, C.B.; Featherman, M. Can Social Role Theory Explain Gender Differences in Facebook Usage? In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Drake, J.R.; Hall, D. When Job Candidates Experience Social Media Privacy Violations. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. On Comparing Results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five Perspectives and Five Recommendations. Mark. ZFP 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afthanorhan, A.; Awang, Z.; Aimran, N. An Extensive Comparison of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for Reliability and Validity. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2020, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.; Gefen, D. Validation Guidelines for IS Positivist Research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Asbari, M.; Santoso, T.I.; Sunarsi, D.; Ilham, D. Education Research Quantitative Analysis for Little Respondents. J. Studi Guru Dan Pembelajaran 2021, 4, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez-Turan, A. Does Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) Reduce Resistance and Anxiety of Individuals towards a New System? Kybernetes 2019, 49, 1381–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. The Relative Importance of Perceived Ease of Use in IS Adoption: A Study of E-Commerce Adoption. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, M.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.-K.; Saarinen, T.; Tuunainen, V.; Wassenaar, A. A Cross-Cultural Study on Escalation of Commitment Behavior in Software Projects. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, M.K.; Thatcher, J.B. Moving beyond Intentions and toward the Theory of Trying: Effects of Work Environment and Gender on Post-Adoption Information Technology Use. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 427–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Micevski, M.; Cadogan, J.W. Users’ Ethical Perceptions of Social Media Research: Conceptualisation and Measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 124, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, R.; Chen, R.; Kim, D.J.; Chen, K. Effectiveness of Privacy Assurance Mechanisms in Users’ Privacy Protection on Social Networking Sites from the Perspective of Protection Motivation Theory. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 135, 113323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berings, D.; Adriaenssens, S. The Role of Business Ethics, Personality, Work Values and Gender in Vocational Interests from Adolescents. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, J.; Hassan, Y. Batting Outside the Field: Examining E-Engagement Behaviors of IPL Fans. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E.; Liu, A.Y.; Shen, W.C. User Trust in Social Networking Services: A Comparison of Facebook and LinkedIn. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-W.; Huang, S.Y.; Yen, D.C.; Popova, I. The Effect of Online Privacy Policy on Consumer Privacy Concern and Trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Araujo, B.; Tam, C. Why Do People Share Their Travel Experiences on Social Media? Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K.S.; Ancillo, A.d.L.; Gavrila, S.G. The Role of Cultural Values in Social Commerce Adoption in the Arab World: An Empirical Study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Riaz, M.; Haider, S.; Alam, K.M.; Sherani; Yang, M. Information Sharing on Social Media by Multicultural Individuals. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Hu, C.; Chauhan, S.; Gupta, P.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Mahindroo, A. Social Commerce: A Bibliometric Analysis and Future Research Directions. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 29, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouibah, K.; Al-Qirim, N.; Hwang, Y.; Pouri, S.G. The Determinants of EWoM in Social Commerce: The Role of Perceived Value, Perceived Enjoyment, Trust, Risks, and Satisfaction. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, O. Social Networking Services and Social Trust in Social Commerce: A PLS-SEM Approach. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhan, M.; Dewani, P.P.; Nigam, A.; Vaz, D.; Ogbeibu, E.A.A. Exploring Customer Engagement on Social Networking Sites. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqrin, A.; Mutambik, I.; Alomran, A.; Gauthier, J.; Abusharhah, M. Factors Influencing Public Trust in Open Government Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Profiles | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 10 |

| Female | 10 | |

| Social commerce experience | <3 years | 5 |

| 3 to 5 | 11 | |

| 6 to 10 years | 4 | |

| Professional background | Humanities | 14 |

| Sciences | 6 | |

| Participant Characteristic | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 133 |

| Female | 132 | |

| S-commerce experience | <3 years | 90 |

| 3 to 5 | 99 | |

| 6 to 10 years | 76 | |

| Professional level | Student | 77 |

| Qualified | 178 | |

| Retired | 10 | |

| Age | <25 | 101 |

| 25–50 | 141 | |

| >50 | 23 | |

| Factors | Kurtosis Statistic (Male–Female) | Skewness Statistic (Male–Female) |

|---|---|---|

| Intention | 1.358 | −1.053 |

| Behaviour | −0.485 | −0.351 |

| PUCI | −0.766 | −0.253 |

| PCPI | 0.679 | −0.949 |

| AAPP | 1.326 | −1.577 |

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | I will continue to share information for social commerce purposes. | 0.85 | [38] |

| I intend to continue frequently sharing information for social commerce purposes. | 0.86 | ||

| Sharing information for social commerce purposes will continue to be part of my daily activities. | 0.87 | ||

| Behaviour | I often share information for social commerce purposes. | 0.88 | [57] |

| I am happy to share my experiences of social commerce with other users. | 0.89 | ||

| I often share information for social commerce purposes. | 0.85 | ||

| CUPI | I worry about how social commerce platforms use my personal data. | 0.84 | Self-developed, based on the qualitative data and [48]. |

| It frequently concerns me when a social commerce platform demands personal data. | 0.84 | ||

| I am against providing personal data to social commerce platforms. | 0.83 | ||

| I have concerns that my personal data is passed on to third-parties by social commerce platforms. | 0.81 | ||

| PCPI | Having control of your own personal data is essential for privacy. | 0.84 | Self-developed, based on the qualitative data and [59]. |

| I feel more confident when I can control the information I supply to a social commerce platform. | 0.83 | ||

| Privacy settings are important for controlling data provided to a social commerce platform. | 0.82 | ||

| I am more likely to take part in social commerce when I can control the use of my personal information supplied to the platform. | 0.81 | ||

| AAPP | I believe privacy policies reflect a social commerce platform’s commitment to protecting users’ privacy. | 0.80 | Self-developed, based on the qualitative data and [60]. |

| I believe that privacy statements mean that my personal information will be properly safeguarded by social commerce platforms. | 0.78 | ||

| I feel confident that social commerce platforms genuinely try to comply with their privacy statements. | 0.83 | ||

| I believe that privacy policies on social commerce platforms are an important and effective approach to building trust among users. | 0.81 |

| Constructs | CA | CR | AVE | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISI | IS | CUPI | PCPI | AAPP | ||||

| Intention | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.84 | ||||

| Behaviour | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.85 | |||

| PICU | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.84 | ||

| PIC | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.82 | |

| AEPP | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.79 |

| Hypothesis | Standardised Path Coefficient | T Value | Support? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: CUPI has a significant impact on users’ intention to share private information for the purpose of engaging in s-commerce. | 0.38 | 5.55 *** | YES |

| H3: AAPP has a significant impact on users’ intention to share private information for the purpose of engaging in s-commerce. | 0.41 | 5.59 *** | YES |

| H5: PCPI has an impact on users’ intention to share private information for the purpose of engaging in s-commerce. | 0.34 | 5.10 *** | YES |

| H7: The intention to share personal information influences users’ information sharing behaviour. | 0.75 | 6.56 *** | YES |

| Fit Index | Results | Recommended Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit measures | ||

| Chi-Square (χ2/DF) | 2.21 | <3.0 |

| RMSEA | 0.043 | <0.05 |

| GFI | 0.938 | >0.90 |

| SRMR | 0.939 | >0.80 |

| Incremental fit measures | ||

| AGFI | 0.931 | >0.90 |

| NFI | 0.953 | >0.90 |

| IFI | 0.951 | >0.90 |

| CFI | 0.976 | >0.90 |

| Parsimonious fit measures | ||

| PNFI | 0.673 | >0.50 |

| PGFI | 0.632 | >0.50 |

| Hypothesis | Female (n = 132) | Male (n = 133) | Standardised Comparisons of Paths | Support? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardised Path Coefficient | t-Value | Standardised Path Coefficient | t-Value | Δ Path (Female–Male) | ||

| H2. | 0.61 *** | 5.58 | 0.46 ** | 4.94 | 0.15 | YES |

| H4. | 0.51 *** | 5.11 | 0.37 ** | 3.21 | 0.14 | YES |

| H6. | 0.62 *** | 5.42 | 0.47 ** | 4.90 | 0.15 | YES |

| H8. | 0.71 *** | 5.72 | 0.54 *** | 5.15 | 0.17 | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mutambik, I.; Lee, J.; Almuqrin, A.; Zhang, J.Z.; Baihan, M.; Alkhanifer, A. Privacy Concerns in Social Commerce: The Impact of Gender. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712771

Mutambik I, Lee J, Almuqrin A, Zhang JZ, Baihan M, Alkhanifer A. Privacy Concerns in Social Commerce: The Impact of Gender. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712771

Chicago/Turabian StyleMutambik, Ibrahim, John Lee, Abdullah Almuqrin, Justin Zuopeng Zhang, Mohammed Baihan, and Abdulrhman Alkhanifer. 2023. "Privacy Concerns in Social Commerce: The Impact of Gender" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712771

APA StyleMutambik, I., Lee, J., Almuqrin, A., Zhang, J. Z., Baihan, M., & Alkhanifer, A. (2023). Privacy Concerns in Social Commerce: The Impact of Gender. Sustainability, 15(17), 12771. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712771