Abstract

Background: Enterprises’ digital transformation is an important issue in the digital era. Exploring how digital transformation can be implemented successfully within enterprises is of considerable theoretical and practical significance. From the perspective of employee learning, this study focuses on employees and aims to establish the theoretical linkage between employees’ perception of enterprise digital capability and their sustainable performance. Methods: A survey using the random sampling technique was adopted to collect data from a large professional data platform. A multi-wave survey featuring 433 full-time Chinese employees was conducted using path analyses to test the hypotheses. Results: The results of the path analyses showed that: (1) employee learning and unlearning mediate the relationship between employees’ perception of an enterprise’s digital capability and their sustainable performance; (2) communication feedback strengthens the positive effects of perceived enterprise digital capability on learning, as well as on unlearning; and (3) the integrated moderated mediation model is valid. Conclusion: This paper proves that during enterprises’ digital transformation, employees’ perception of the enterprise’s digital capability promotes employee sustainable performance via both learning and unlearning. Communication feedback strengthens the above relationships. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature on digital transformation and highlights employee-learning-related organizational management issues, shedding light on the practice of enterprise digital transformation.

1. Introduction

In the era of the digital economy, a growing number of enterprises have opened up pathways towards digital transformation [1]. Enterprise digital transformation is a process based on the application of digital technologies to improve business processes, promote business model innovation, and consolidate synergy so as to increase value creation and achieve sustainable development [2]. Digital transformation involves not only technological advances, but also profound organizational changes. During this process, employees are not passive recipients, but rather the main facilitators of change. Their mindsets, values, and attitudes toward digital transformation are crucial in order for enterprises to gain competitive advantages in the future. Thus, in this inevitable, dynamic and complex process, employees need to be able to continuously learn in order to improve their digital literacy and to cope with this profound organizational change. In this paper, we seek to address the following question: from the perspective of individual learning, what is the process underlying employee adaptation to organizational digital transformation? That is, how and when does an employee’s perception of enterprise digital capability (hereafter referred to as perceived digital capability) exerts an influence on their perceived importance of workplace outcomes with respect to sustainable performance?

Employee sustainable performance describes the contribution of an employee to their own and the organization’s sustainable development. It involves task and relational aspects [3], and refers to the demonstration of high-level, stable, and sustainable performance by employees in the context of their work performance sustained over a longer timeframe [3]. Sustainable performance not only focuses on employees’ short-term achievements and goals, but also on their development and the continuous improvement of their abilities in the long term. With the rapid development of digital technologies accelerating the transformation of the workplace, higher demands are being placed on employees with respect to sustainable performance. While means of promoting employees’ sustainable performance during this critical phase remain unclear, on an organizational level, the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise sustainable performance has been explored in detail, with mixed conclusions [4,5], indicating the existence of critical contingency factors. Even though there is extant research stressing the important role of knowledge sharing [6] and ethical leadership [7] in enhancing employees’ sustainable performance, insufficient attention has been paid to the role of enterprise digital transformation on employee sustainable performance and its underlying mechanisms on the individual level. As a result, scholars have advocated for further exploration on the level of the individual employee, so as to form a comprehensive understanding of how employees adapt to and cope with digital transformation and further their achievement of sustainable development [8,9,10].

Zooming in on the micro context of workplace digital transformation, from the employees’ perspective, digital transformation is placing new demands on their knowledge and skills. The utilization of new equipment, digital tools, new collaboration processes, and synergic models as a result of the shift towards digital technology results in there being a huge gap between an employee’s job requirements and their actual competence [8]. These gaps not only impose new learning requirements—they also provide learning opportunities; that is, in order to bridge these gaps and meet the demands of a job, employees need to learn proactively [11]. Thus, in the context of enterprise digital transformation, employees’ ability and motivation regarding learning have become key factors in promoting employee performance and long-term sustainable development [12]. Learning refers to an individual’s initiative with respect to acquiring new knowledge, skills, and capabilities during work [13]. Through learning, employees can accumulate knowledge and improve their skills to achieve their own growth and meet their own needs, and to promote the overall sustainable development of the organization. Employees who learn are more willing to explore and actively participate, and to adopt creative, open-minded ways of thinking [14]. Meanwhile, outdated and redundant experience and knowledge can hinder the further transformation and sustainable development of employees and organizations. Thus, unlearning is essential for acquiring new knowledge and skills [15] as well. Unlearning refers to the process by which learners consciously discard and abandon misleading and outdated knowledge, experience, skills, and behaviors in order to better meet the requirements of digital transformation and improve sustainable performance [16,17]. Research has been performed indicating that unlearning helps organizations and employees to actively respond to the internal and external dynamic environment, break the inertia of thinking, break through the limitations of old frameworks, discard and update outdated knowledge and experience in a timely fashion, and in turn facilitate the further achievement of sustainable development [18,19]. Thereby, in the context of digital transformation, employees are not only required to learn and absorb new knowledge and skills, but also to engage in unlearning.

Further, extant research suggests that employee learning is not necessarily fostered by intrinsic motivation, and a supportive managerial environment [20] also serves a pivotal leveraging role. The connotation of human resource management (HRM) in the digital era suggests taking into account the mutual demands of employees and organizations, emphasizing their integration and balance [21]. Therefore, eligible managerial practice under the circumstance of digital transformation should not only encourage employees to take the initiative to learn, but also strive to create a favorable environment and provide essential channels, opportunities, and resources for employees to unlearn. Such external support could assist employees in accelerating the process of human–technology integration and overcoming the pain and discomfort caused by digital transformation. Accordingly, regarding employee management, critical questions attracting much scholarly attention have included what HRM practices should be adopted during and after digital transformation [22,23,24]. Communication feedback is an essential component of developmental HRM, which can help managers to better understand and meet the individual needs of employees and convey organizational goals to employees to achieve the organic integration of the organization and employees [25]. Through communication feedback, employees can obtain information that helps to improve their performance, reduces uncertainty, allows them to explore the prospects of new tasks, and develops a sense of responsibility. Employees can also express their feelings and voice their opinions to managers, cultivating a digital-transformation-friendly leadership style and an adaptive work environment [26]. Organizational formal and informal communication feedback channels are inclined to create more employee learning opportunities [27]. A sound and effective communication feedback mechanism can facilitate an organization to establish smooth communication channels and platforms for employees to express their opinions. Meanwhile, it empowers managers to better understand how to listen to and respect subordinates’ views and provide them with high-quality feedback. Communication feedback can help employees to obtain access to more digital learning resources and enhance their learning autonomy [27]. Moreover, it reconciles the Sustainable Developmental Goals between enterprises and employees and promotes the coordinated, sustainable development of employees and organizations, coinciding with the connotation of developmental HRM practice [25].

To sum up, the knowledge of how and when digital transformation influences employee sustainable performance remains limited. Following this vein, this study proposes a moderated mediation model to explore the mechanism and boundary conditions regarding how employees’ enterprise digital capability perception affects their sustainable performance through learning and unlearning, respectively. Furthermore, from the perspective of developmental HRM practice, our study goes beyond prior coarse-grained research and reveals the boundary condition of communication feedback in enhancing the abovementioned associations. The research process of this paper is organized as follows. We begin in Section 2 by describing employee learning and unlearning during digital transformation and further build theoretical linkages between employees’ perceptions of the enterprise’s digital capability and employee sustainable development. Section 3 focuses on describing the data collection process and our methodology. Section 4 presents the procedures of hypotheses tests using path analyses. In the end, Section 5 includes the interpretation of our results, practical implications, and future directions.

This study aims to contribute to the research field in several ways: first, we focus on the sustainable performance of micro individuals in the context of macro enterprise digital transformation. Thus, it broadens the knowledge of the impact of perceived digital transformation on employees’ subsequent behavior and more distal performance. Second, based on the perspective of learning, this study proves the dual-facilitating role of both learning and unlearning in transmitting the influence of enterprise digital capability to employee sustainability. Thus, it reveals the underlying mechanism and provides empirical evidence regarding encouraging employees to perform better during digital transformation. Finally, we introduce communication feedback as a moderating variable, which helps researchers to further understand how to cultivate a favorable context for employees during digital transformation.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Employee Sustainable Performance

This study focuses on the impact of digital transformation on employee sustainable performance. The concept of sustainability related to work was first proposed by Docherty et al. in 2002 [28]. Based on relevant studies, scholars such as Ji proposed that employee sustainable performance refers to the high-level, stable, and sustainable performance exhibited by employees in long-term and sustained work performance [3]. Employee sustainable performance emphasizes the sustainability and reliability of performance. Under various work scenarios and conditions, employees can maintain a stable and sustained high level of performance over a long period. Sustainable performance focuses on employees’ actual work achievements and contributions to organizational goals, emphasizing their continuous learning and personal development. This study focuses on the impact of employees’ learning and unlearning on their sustainable performance in enterprise digital transformation.

2.2. Employee Learning and Unlearning

This study also focuses on employee learning and unlearning in digital transformation. Learning and unlearning help employees to cope with job insecurity and new job demands in the digital era. It is a measure for employees to improve their sustainable performance in response to the changing employment environment. Employee learning refers to an individual’s initiative behavior to acquire new knowledge, skills, and abilities at work [13]. The term “unlearning” was introduced to social science by Dewey [29], an American educational philosopher, in his book “Experience and Education”. Postman and Stark [30] once categorized “unlearning” into learning and proposed it as an extension of conventional learning. As research findings accumulated, Hedberg [16] pointed out that organizational experience may generate inertia and thus hinder employees’ ability to learn and develop in a new environment. Then, unlearning was defined as a process in which learners sublate or discard outdated knowledge [16]. Most of the research on unlearning has focused on the organizational level, which was introduced into the field of management by Nystrom and Starbuck [31]. They emphasized the importance of unlearning in response to organizational crises. Since then, insufficient unlearning has been regarded as one of the primary reasons why enterprises insist on following previous routines, fail to adapt to the ever-changing external environment, and encounter crises. At the organizational level, Akgün et al. [18] defined unlearning as eliminating organizational memory and argued that organizations must abandon established beliefs and methods to cope with new market-related and technical information. At the individual level, unlearning refers to intentionally eliminating old knowledge and creating space for new knowledge [17]. Despite the development of the literature, Howells and Scholderer [32] raised concerns about whether unlearning is an independent concept. Based on their literature review, they argued that Hedberg’s [16] definition of unlearning lacks an empirical basis, meaning that the concept of unlearning has rarely appeared in previous studies.

In contrast, with follow-up rigorous quantitative analyses, more scholars hold a supportive view. For example, Visser [33] argued that unlearning can be considered an independent concept because it contains denying and is close to learning. This emphasizes the need to reassess its position in learning research, especially in second-order and double-loop learning. Peschl [34] argued that unlearning should be viewed as an adaptive process in which old and new knowledge interact in mutual fading out and fading in. Mixed methods have been used at the individual and organizational levels to prove unlearning as empirically warranted and to triangulate the differences at different levels. Durst et al. [8] disentangled its operationalization, research methodology, and level of analysis. To sum up, unlearning is not only an expected prerequisite for learning; instead, it opens up new possibilities for “not knowing” and “not acting”. The independent role of unlearning is verified.

Recently, the research field of unlearning has been rejuvenated. Kim and Park conducted a literature review and identified 30 antecedents and 44 outcomes that promote unlearning at the individual, group, and organizational levels. They proposed that employee unlearning can affect organizational learning, goal orientation, skill improvement, and work engagement [35]. Scholars have also studied the impact of goal orientation and unlearning on individual exploration activities, suggesting their predicting roles [36]. Yin validated a serial mediation model, proposing that a paradoxical mindset indirectly enhances work engagement through seeking challenges and unlearning in series [37]. The impact of organizational unlearning on dynamic capabilities and product innovation performance is also validated [38]. This study stresses the need for employees to learn and unlearn to develop digital mindsets, control digital tools and equipment, and adapt to an efficient and agile digital management process. During this, employees are encouraged to learn and unlearn to cope with changes and keep pace with the overall digital transformation development.

2.3. The Mediating Effect of Employee Learning and Employee Unlearning

The premise of employee management in the new digital working scenario is based on understanding the relationships between employees and organizations and the relationships between employees and their jobs. One of the core challenges that employees face is adapting to new job demands brought about by implementing digital technologies and applying digital tools [39,40]. Employee sustainable performance indicates employees contributing to their and the organization’s sustainable development. It involves task and relational aspects [3].

On the one hand, to conquer new work challenges, employees need to actively learn to improve their adaptive and subsequent sustainable performance [41]. Extant research has shown that during organizational change, employees who are more willing to learn and open to changes tend to demonstrate high adaptability in the changing environment [42]. This is because learning can effectively address the problems of failing to meet performance requirements due to insufficient digital knowledge and a lack of digital capacity. With abundant digital knowledge, employees can be better involved in and engaged in new work environments. In this way, employees can break through the boundaries of their original capabilities and complete the transformation and upgrading of their work roles, cultivate positive states in the changing external environment, and further form an upward spiral to contribute to their sustainable development.

On the other hand, an employee needs to learn about acquiring new knowledge and skills “from 0 to 1” and “unlearning”. Unlearning emphasizes the importance of acquiring new knowledge and skills while avoiding the limitations of previous paradigms. Employees should have the courage to question, reflect on and discard outdated knowledge and actively abandon old practices incompatible with organizational sustainable development. This helps to motivate employees to innovate continuously. Employees’ working environment and job requirements undergo profound changes during digital transformation. The extant knowledge and experience cannot cope with new organizational management problems. Employees ought to surmount the inertia of prior successful paths and avoid getting stuck in a confidence trap. Reluctance or inability to discard old knowledge can hinder creativity and innovation when employees are unwilling to see new knowledge they have not yet acquired or mastered as practical or applicable [43]. Old knowledge structures and cognitive models hinder adaptations to new environments. Before employees try new ideas, they must discard old ideas by identifying their shortcomings [32]. Employee unlearning comes first, then group unlearning, which is also considered critical in team learning and innovation [18]. Previous studies have shown that unlearning accelerates knowledge transfer and facilitates knowledge development [44,45]. Employees who engage in unlearning can better balance their work–life relationships and deeply engage in work. Research also shows that performing unlearning facilitates higher-level sustainable performance [46,47]. Unlearning is always productive since it can reduce the impact of old knowledge on cognitive and behavioral processes and help to make lasting changes in personal and organizational memory [48]. Thus, unlearning some old knowledge and experience may be beneficial to embrace the future better. It has been shown that employee unlearning improves the efficiency of knowledge integration and absorption efficiency and fosters cognitive system changes, helping to improve sustainable performance [16,49].

Notably, learning is not the opposite of unlearning; in contrast, they are complementary. First, learning depicts a process of moving from “unknown” to “known,” acquiring knowledge or skills through experiencing and practicing. Unlearning is a unique type of learning that involves consciously updating knowledge, values, and behaviors. van Leijen Zeelenberg et al. [50] suggest that, in the implementation process, abandoning existing routines should receive equal attention as learning to use new routines to remove some of the barriers to learning. Thus, learning and unlearning are processes in which individuals constantly explore knowledge and seek answers in the face of new situations and problems [16,17]. Second, learning shares the connotation of unlearning. When dealing with changes in work content and methods brought about by digital transformation, employees who unlearn are more likely to acknowledge their deficiencies in knowledge and skills. In the digital transformation process, knowledge, experience, and answers to emerging questions are attuned to be complex, dynamic, and obscure. In this vein, we show that both learning to reflect on and acquire existing knowledge and unlearning to bring forth the new through the old are the crux of employees’ adaption to digital transformation. Thus, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Employee learning mediates the relationship between perceived enterprise digital capability and sustainable performance.

Hypothesis 2.

Employee unlearning mediates the relationship between perceived enterprise digital capability and sustainable performance.

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Communication Feedback

External environment factors could cultivate the willingness and the extent to which employees conduct learning-related behaviors [51]. As the research of Howells and Scholderer [32] shows, unlearning can be and should be managed. According to the organizational change literature, during digital transformation, organizations’ communication with employees around the vision, purpose, and value of change could help employees to better adjust their mindset, respond positively, and adapt to change [9,52]. Communication feedback refers to the organizational and managerial practices of establishing smooth communication channels, respecting employees’ rights and opinions, encouraging employees to participate, and enabling them to obtain direct and transparent information about their performance. It is also vital to create learning opportunities during employee learning and unlearning. Effective communication feedback indicates that employees can pass on information such as learning demands, work support, opinions, and suggestions to leaders and organizations [25]. Also, when employees engage in unlearning, they feel overwhelmed by strong emotions, such as threat, embarrassment, defensiveness, and resistance. During this, a safe and supportive environment is necessary to prevent these deep learners from undergoing mental breakdowns and collapses [33]. Therefore, a sound communication feedback mechanism can continuously empower employees to grasp the overall situation and help them cope with the discomfort and challenges related to digital transformation, providing guarantees for employees to learn, unlearn and achieve sustainable development.

When the level of communication feedback in the organization is high, employees can promptly identify pitfalls and reconcile problems they encounter during learning and unlearning, seek solutions, and obtain constructive advice from the organization. Research suggests that learning-related behaviors occur when employees recognize the gaps between actual work outcomes and aspirational goals [53]. At the same time, organizations with a high level of communication feedback tend to value employees’ opinions and suggestions, and always promise to provide employees with insightful feedback and solutions. Such feedback loops portray the essence of the continuous iteration of learning itself. In this vein, employees can leverage these feedback loops to update their knowledge base and structure. In contrast, when organizational communication feedback is low, scant communication channels and poor feedback can inhibit employees’ understanding of the path and requirements of enterprise digital transformation and hinder them from gaining valuable information and practical feedback in response to digital transformation. As a result, activities of learning and communicating are impeded, restricting employees from keeping up with the development of new knowledge and skills.

Communication feedback is also a crucial component of developmental HRM. Since the ultimate goal of developmental HRM is to achieve mutual development of both organizations and employees, it is important that the communication feedback between the two parties is effective and efficient [25]. Effective communication feedback helps to reduce barriers for employees during learning and unlearning and advances the interconnection between employees and the internal and external environment, demonstrating practical significance in the digital era.

In addition, extant organizational change research has proven that the communication quality between organizations and employees can promote more employee job-crafting behaviors and reinforce organizational change implementation [54], which provides us with empirical evidence upholding the moderating role of communication feedback. Therefore, this study proposes the enhancing effect of communication feedback on the relationships between employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and their learning and unlearning, respectively. These rationales lead to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3.

Communication feedback enhances the positive relationship between perceived enterprise digital capability and employee learning, such that the relationship is stronger when communication feedback is higher than lower.

Hypothesis 4.

Communication feedback enhances the positive relationship between perceived enterprise digital capability and employee unlearning, such that the relationship is stronger when communication feedback is higher than lower.

2.5. An Integrated Model

Taken together, this study further posits a moderated mediation model linking employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability to their sustainable performance through learning and unlearning, of which the dual paths are further enhanced by communication feedback. When the level of communication feedback is high, the mediating effects of both learning and unlearning become stronger. Consequently, we put forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5.

Communication feedback enhances the indirect effect of perceived enterprise digital capability on sustainable performance through employee learning, such that the indirect effect is stronger when communication feedback is higher than lower.

Hypothesis 6.

Communication feedback enhances the indirect effect of perceived enterprise digital capability on sustainable performance through employee unlearning, such that this indirect effect is stronger when communication feedback is higher than lower.

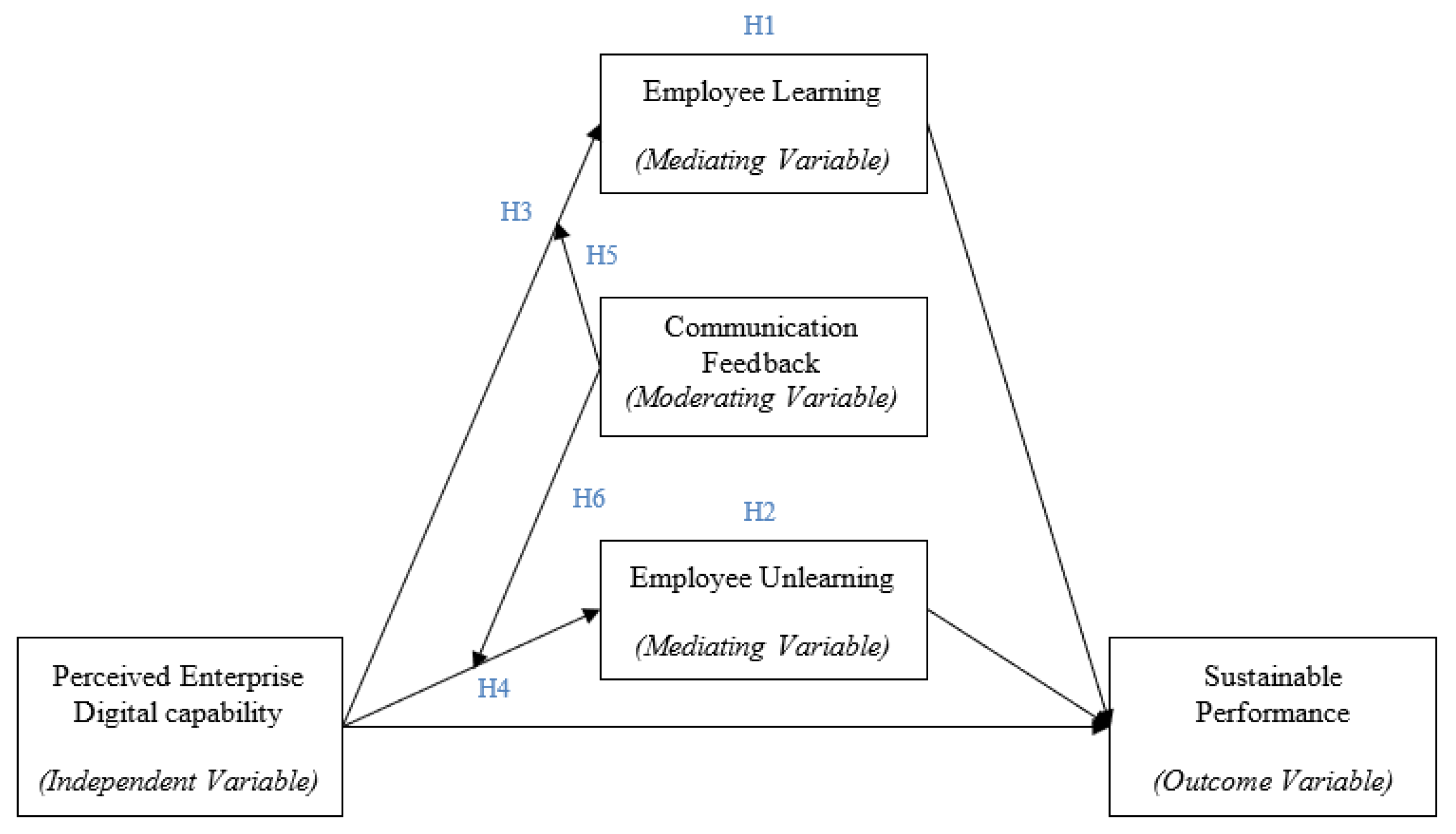

Our theoretical model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model. Notes: H denotes Hypothesis. H1 and H2 are mediation effects; H3 and H4 are moderation effects; H5 and H6 are moderated mediation effects.

3. Method

3.1. Samples and Procedures

We collected survey data using a random sampling technique via Credamo (https://www.credamo.com/, 21 August 2023), a professional online data collection platform in China similar to Qualtrics. There are more than three million registered users in Credamo covering all kinds of backgrounds. We registered our sample demand on the platform, including sample size (i.e., 500 participants) and sample qualifications (i.e., currently employed employees). The platform then sent survey invitations to the qualified users in the participant pool. With the help of AI technology and an algorithm, the participants were chosen using a random sampling technique. In order to minimize the effect of common method variance [55], a two-wave study (i.e., Time 1 and Time 2) was designed with a one-month time interval. Participants who applied for our research and were validated by the platform received online survey links. An online survey was utilized since it enabled participants to complete and submit the questionnaires at any time and place. In order to address participants’ concerns, we guaranteed total anonymity, voluntariness and academic use only in our research. In addition, to further enhance data quality and participation rate, each participant received a monetary reward after completing the survey. The participants received an extra monetary bonus if their two-wave surveys matched.

In Wave 1, all 500 participants completed the Time 1 survey. The participants were invited to rate their perceived enterprise digital capability and demographic information (i.e., gender, age, educational level, position level, and tenure). In Wave 2, one month later, we sent Time 2 survey links to all the 500 participants in our sample database. We invited them to self-evaluate their learning, unlearning, and sustainable performance and assess their organizational communication feedback. A total of 460 questionnaires were obtained in Wave 2. After excluding the invalid answers with missing values, too short a response time, or inconsistent logic, we obtained a final sample of 433 participants. The valid answer rate was 86.6%. T-test analysis showed no significant difference (p > 0.05) in gender, age, educational level, position level and tenure between the participants who completed the two-wave survey and those who only participated in Wave 1, indicating that our sample loss was random.

Among the 433 participants, 185 were male, and 248 were female. With regard to age, 40.0% were between the ages of 21 and 30, and 52.2% were between the ages of 31 and 40. Regarding educational background, 69.1% had bachelor’s degrees. In relation to positional levels, 34.2% were frontline-level employees, 36.7% were frontline-level managers, and 22.4% were middle-level managers. Their average tenure was 6.18 years; the standard deviation [SD] was 4.24. Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

3.2. Measures

We adopted the standard translation and back-translation procedures to create Chinese version measurements [56]. All measures were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, to 7 = strongly agree).

3.2.1. Perceived Enterprise Digital Capability

In Wave 1, we asked participants to evaluate their perceived enterprise digital capability using measures of digital capability adapted from [57,58,59]. The scale contained three dimensions of digital sense capability, digital capture capability, and digital transformation capability. Each dimension included five items. For digital sense capability, a sample item was “Our company is able to analyze the signals scouted and analyze the digital scenarios of the future”. Cronbach’s alpha (α) value for this sub-dimension was 0.85. For digital capture capability, a sample item included “Our company is able to reallocate resources quickly” (α = 0.86). For digital transformation capability, a sample item was “Our company is able to leverage digital knowledge from within and outside the organization” (α = 0.81). Following previous research approaches [59], we treated digital capability as a unidimensional construct. The overall Cronbach’s alpha value was ideal (α = 0.94).

3.2.2. Employee Learning

In Wave 2, we used the new knowledge acquisition scale [60,61] to measure employee learning. The scale included six items and has been proven to possess high reliability and validity when applied to the individual level [61]. A sample item was “During digital transformation, I collect information through informal means (e.g., lunch or social gatherings with customers and suppliers, trade partners and other stakeholders)” (α = 0.75).

3.2.3. Employee Unlearning

In Wave 2, following recommendations, we modified the four-item measurement of unlearning and adapted it to the individual level [16,18,62]. A sample item included “During digital transformation, I permit new knowledge, even that which is a conflict with well-accepted experiences and technologies” (α = 0.70).

3.2.4. Communication Feedback

In Wave 2, participants assessed their perceived level of organizational communication feedback with a three-item scale [63,64,65]. For example, “Our company respects employees’ right to speak, and encourages employees to speak up” (α = 0.79).

3.2.5. Sustainable Performance

Sustainable performance was measured with the scale developed and validated by Ji and colleagues [3]. A sample item was “During my entire career, I will be able to continuously achieve the objects of my job” (α = 0.75).

3.2.6. Control Variable

Enterprise digital transformation is inherent in a profound organizational change. Previous research has found that employee gender, tenure, and educational level could exert impacts on employees’ attitudes and behaviors in the context of organizational change [66]. Therefore, we included employee gender, age, educational level, position level and tenure as control variables to eliminate their potential impact on our results.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 reports the descriptive analyses and correlations of focal variables. As Table 2 presents, the bivariate correlations are as expected. For example, the correlations between employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and learning (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), unlearning (r = 0.49, p < 0.001) and sustainable performance (r = 0.54, p < 0.001) were significant and positive, respectively, providing preliminary support for our hypotheses. Moreover, according to Table 2, there is individual heterogeneity in our study. For example, employee age is positively related to unlearning (r = 0.10, p < 0.05), and educational level is positively related to learning (r = 0.13, p < 0.01). Employee position level is positively related to perceived enterprise digital capability (r = 0.11, p < 0.05), learning (r = 0.18, p < 0.001), unlearning (r = 0.13, p < 0.01), and communication feedback (r = 0.19, p < 0.001). In addition, employees with longer tenure tend to perceive a higher level of enterprise digital capability (r = 0.10, p < 0.05) and perform better (r = 0.10, p < 0.15).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities 1.

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with Mplus 7.4 [67] to examine the distinctiveness of the five focal variables. The standardized factor loading values for each item all satisfy the criteria recommendation (>0.40) [68]. Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, the hypothesized five-factor model has advantageous model fit indices compared to all of the alternative models (χ2(517) = 790.62, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04), indicating that the variables are distinct from each other.

Table 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis 2.

Since all the data were self-reported, common method variance may contaminate our results. Therefore, we performed Harman’s single-factor test [55]. As shown in Table 3, the one-factor model has a much poorer model fit compared with the hypothesized five-factor model (χ2(527) = 1672.57, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.82, TLI = 0.81, SRMR = 0.07) [69]. In addition, we conducted the exploratory factor analysis with SPSS 26.0. The first factor accounts for 36.75% of the variance, which is lower than the threshold of 50%. Thus, these results indicate that common method variance was not a serious issue in our findings.

We utilized multicollinearity indices, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance to find out whether multicollinearity was a major concern. The results show that for all predictive variables, the VIF scores ranged from 1.88 to 2.18, which were all well below the 10.0 cutoff value [70,71]. Meanwhile, tolerance values ranged from 0.46 to 0.53, which were all well above the 0.10 cutoff value [70,71]. Thus, multicollinearity was not evident.

4.2. Hypothesis Tests

We conducted path analysis with Mplus to test our hypotheses. Employee gender, age, educational level, position level and tenure were controlled throughout the analysis. Table 4 presents the results of the path analysis.

Table 4.

Path analysis results 3.

4.2.1. Test of Mediation Effect

Hypothesis 1 proposes that employee learning mediates the relationship between employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and their sustainable performance. The results displayed in Table 4 indicate that employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability is positively associated with employee learning (B = 0.29, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). After controlling for the impact of the perceived enterprise’s digital capability, employee learning is positively associated with sustainable performance (B = 0.14, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01). Further, we adopted Preacher et al.’s [72] approach toward construing the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) for estimating indirect effects based on bootstrap-based statistics. Drawing on 1000 resamples, the results show that the indirect effect between perceived digital capability and sustainable performance via learning is 0.04 (SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07], excluding zero). Thus, Hypothesis 1 receives support.

Hypothesis 2 proposes the indirect effect through employee unlearning. The results displayed in Table 4 indicate that employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability is positively associated with employee unlearning (B = 0.32, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). After controlling for the impact of employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability, employee unlearning is positively associated with their sustainable performance (B = 0.28, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). Further, the results based on 1000 bootstrapping resamples show that the indirect effect between perceived enterprise digital capability and sustainable performance via unlearning is 0.09 (SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.13], excluding zero). Hence, Hypothesis 2 receives support.

4.2.2. Test of Moderation Effect

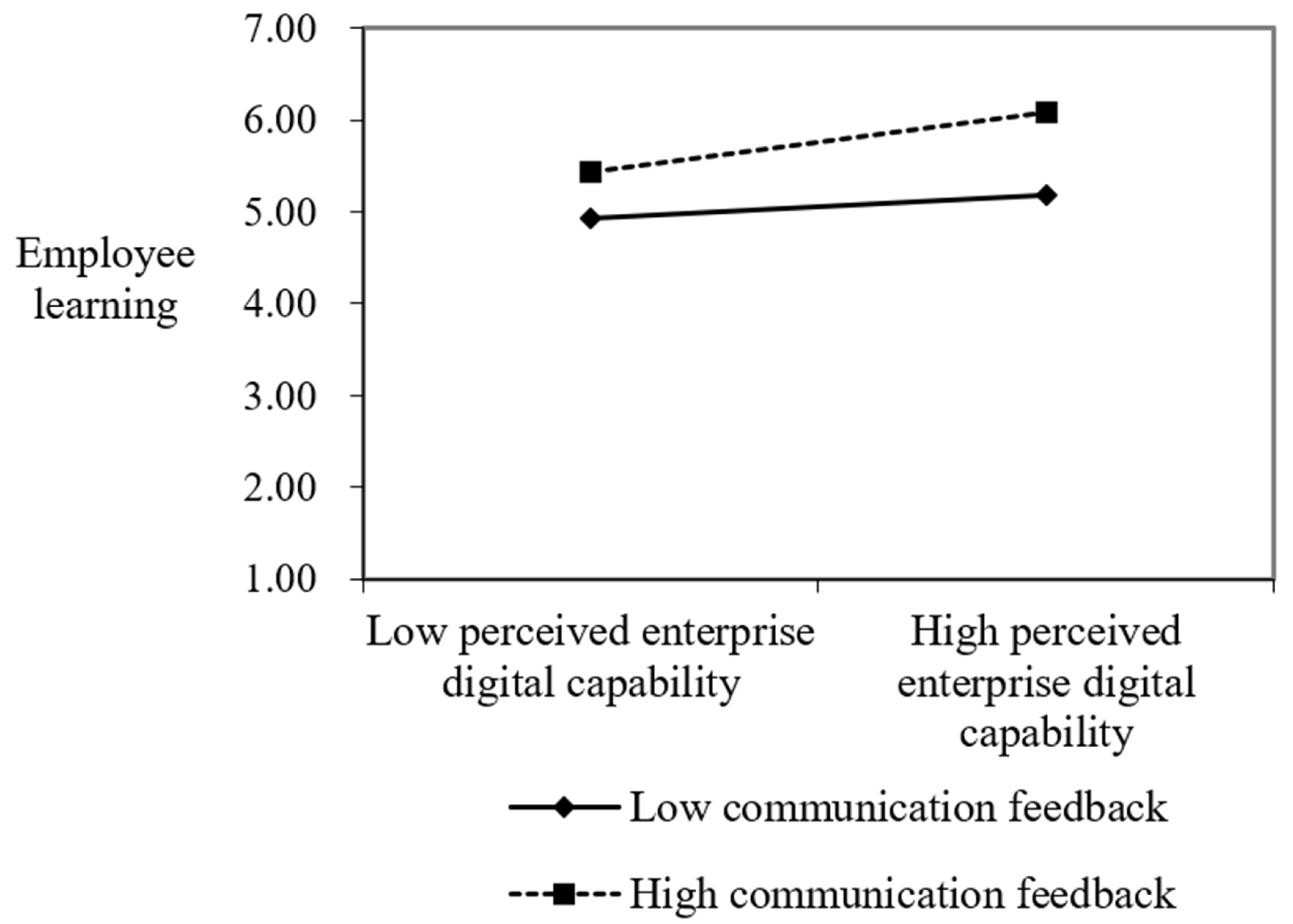

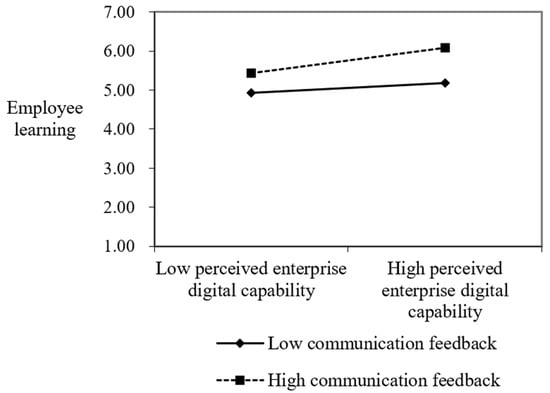

Hypothesis 3 proposes that communication feedback moderates the positive relationships between employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and employee learning. The results presented in Table 4 show that the effect of the interaction term of employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and communication feedback on learning is positive and significant (B = 0.15, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). In addition, in order to further illustrate the moderation, we employed simple slope analysis and plotted the pattern [73] (see Figure 2). The results indicate that when communication feedback is high (one SD above the mean), employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability is positively related to employee learning (B = 0.42, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). In contrast, when communication feedback is low (one SD below the mean), employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability is still positively related to employee learning, while the strength becomes weaker (B = 0.16, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01). The difference between the two simple slopes is significant (B = 0.26, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). Hence, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 2.

The interactive effect of perceived enterprise digital capability and communication feedback on employee learning.

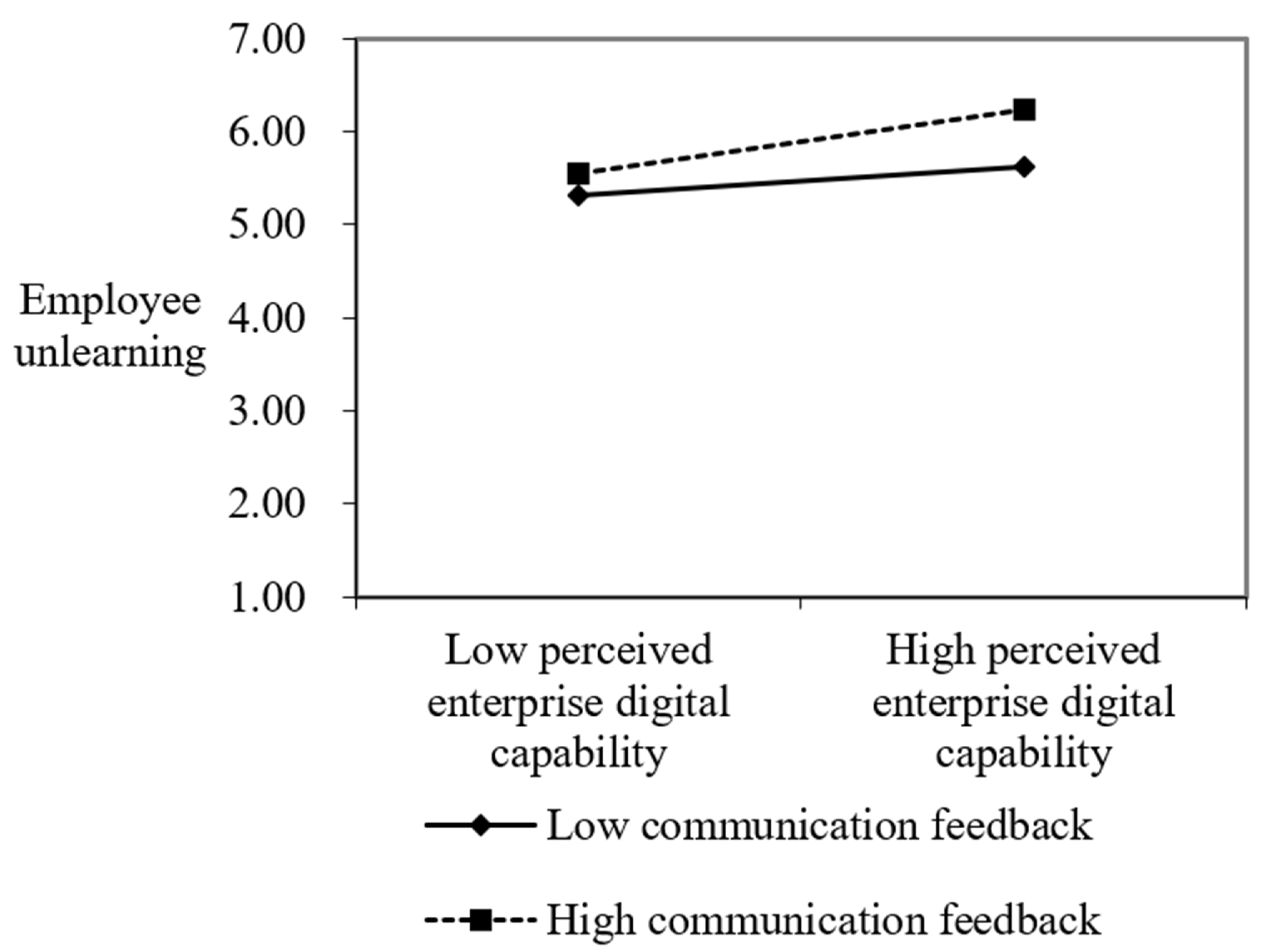

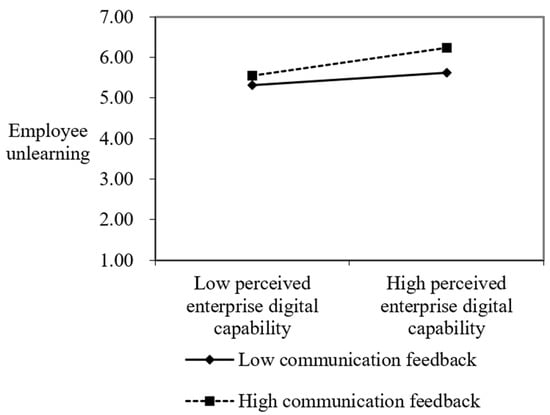

Hypothesis 4 proposes that communication feedback enhances the positive relationships between employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and employee unlearning. The results presented in Table 4 show that the effect of the interaction term of employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and communication feedback on unlearning is positive and significant (B = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). Moreover, the simple slope test results (Figure 3) indicate that when communication feedback is high, employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability is positively related to employee unlearning (B = 0.44, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001). When communication feedback is low, employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability is still positively related to employee unlearning, while the strength of the relationship becomes weaker (B = 0.20, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01). The difference between the two simple slopes is significant (B = 0.24, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01). Hence, Hypothesis 4 receives support.

Figure 3.

The interactive effect of perceived enterprise digital capability and communication feedback on employee unlearning.

4.2.3. Test of Moderated Mediation

Hypothesis 5 proposes the integrated moderated mediation model through learning. The results based on 1000 bootstrapping resamples show that when communication feedback is high, the indirect effect of employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability on sustainable performance via learning is positive and significant (B = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.10], excluding zero). When communication feedback is low, the indirect effect is still positive, but becomes weaker (B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.04], excluding zero). The difference between the two levels is significant (B = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.06], excluding zero). Hence, Hypothesis 5 receives support.

Similarly, Hypothesis 6 proposes the moderated mediation model via unlearning. The results based on 1000 bootstrapping resamples indicate that when communication feedback is high, the indirect effect of employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability on sustainable performance via unlearning is positive and significant (B = 0.13, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.19], excluding zero). When communication feedback is low, the indirect effect is still positive and significant, but becomes weaker (B = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.10], excluding zero). The difference between the two levels is significant (B = 0.07, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.12], excluding zero). Hypothesis 6 is supported.

5. Discussion

This study explores the mechanisms and boundary conditions of enterprise digital transformation on employee sustainable performance at the individual level, and reveals the underlying roles of learning and unlearning. Furthermore, this study extrapolates the moderating role of communication feedback and investigates the conditions under which digital transformation facilitates employee performance. This paper draws the following conclusions from the empirical analysis of two-wave survey data for 433 employees.

First, this paper links digital transformation at the organizational level and sustainable performance at the individual level. Despite the prosperous research development of digital transformation, extant research mainly focuses on its impact on the business model, organizational innovation, and other vital outcomes at the organizational level [2]. However, insufficient attention has been paid to the role of enterprise digital transformation on employee sustainable performance. Our study stresses how digital transformation influences individual performance and broadens the research scope of digital transformation in management.

Second, this paper highlights the mediating effects of employee learning and unlearning. Digital transformation imposes new demands on employee knowledge structures, abilities and work skills. From the perspective of employee learning in enterprise digital transformation, this paper establishes the theoretical linkages between employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability and their sustainable performance through learning and unlearning. Previous research used to regard unlearning as a learning component, exploring the inner connection between learning and unlearning at the organizational level [62,74]. For example, Visser posits that unlearning needs to be embedded in the dynamic learning process and concludes that it fits into the “interruption” phase [33]. This paper validates the dual-mediating role of learning and unlearning at the individual level in digital transformation. In addition, a previous study proposes that organizational unlearning could disrupt current innovation routines and positively relate to the sustainability of digital innovation in manufacturing companies [75]. Thus, this study explicitly stresses the dual roles of learning and unlearning in an employee’s adaptation process to digital transformation.

Third, this paper postulates the moderating effect of communication feedback. In the context of digital transformation, employees’ learning content, learning requirements, and learning procedures have undergone profound changes. Efficient communication feedback is conducive to tracking employees’ current states, encouraging employees to reflect and conduct self-correction promptly to accommodate the new digital transformation requirements better. Previous studies have studied communication feedback in different contexts such as public administration, and found that applying effective communication feedback mechanisms in local government departments can help achieve high productivity [76]. Also, research strives to explore how nowadays, online tools such as Mentimer, Kahot, and third-party business platforms such as Padlet and Jamboard [26] could facilitate communication feedback. This study construes and empirically tests how communication feedback strengthens the indirect effects of employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability on their sustainable performance through learning and unlearning.

Fourth, this paper proposes an integrated moderated mediation model. To be specific, employees’ perceived enterprise digital capability exerts influence on employee sustainable performance through learning and unlearning. Furthermore, the dual-path indirect effects are enhanced by communication feedback, such that when the level of communication feedback is high, the dual-path indirect effects are strengthened.

Notably, in this work we study the issue of digital transformation in the context of China. On the one hand, the digital transformation construction of Chinese enterprises has a particular scale foundation, and the inherent cultural characteristics of Chinese employees pursuing long-term development are conducive to our research on the sustainable performance of employees [77]. On the other hand, most previous research on learning and unlearning has collected data from Western countries [8,34,46]. The lack of digital literacy in the labor force has also seriously restricted the implementation of enterprises’ digital transformation in China. Therefore, by discussing the impact of digital transformation on Chinese employees’ sustainable performance, focusing on improving their learning and unlearning is a crucial way to enhance their digital professional literacy. This also could provide more economical and cost-effective training suggestions for enterprises to implement digital transformation. Our findings broaden the research on employee learning and sustainable performance issues under digital transformation, and we also call for extending our findings to other cultural contexts for testing.

Regarding methodological contributions, to the best of our knowledge, this study not only theorizes and empirically tests the influence of digital capability at the organizational level on employee sustainable performance at the individual level, but also, in adopting the survey method, adapts and modifies the organizational-level measurement of “digital capability” to individual-level “perceived enterprise digital capability” using the referent shift technique, which broadens and enhances the applicability of the measurement.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study enriches the extant literature on sustainable performance, digital transformation and employee learning in several ways.

First, this study broadens the outcomes of digital transformation. The majority of extant research explores the influences of digital transformation at the organizational level (e.g., business model, value creation, organizational performance). Scarce attention has been paid to individual-level related research questions. Exceptional scholars have articulated that the key to achieving breakthroughs during digital transformation lies in the “employee” [24]. In contrast, this study enlarges our understanding of what influences digital transformation can exert on employees, and how these influences occur. Further, this study contributes to sustainable performance by focusing on the impact of enterprise digital transformation on sustainable performance in a macro context at the micro-individual level. From the perspective of employee learning, this study constructs a dual pathway of digital transformation on employee sustainable performance, which enriches and refines the association between enterprises’ digital transformation and employee sustainable performance, and provides a new research direction for enterprise digital transformation.

Second, this study focuses on employees learning issues in the context of digital transformation. This study responds to scholars’ call to pay attention to the analysis and management of employee learning behavior in digital transformation [35]. It explores the impact of enterprise digital transformation on employee learning behavior at an individual level. This study enriches and extracts research on the relationship between digital transformation and employee sustainable performance from the perspective of employee learning, providing new research directions for digital transformation in enterprises. Thus, our study echoes the call for research regarding employees’ changes in attitudes and behaviors when facing digital transformation.

Third, this study further broadens the research scope of the learning literature by highlighting the role of employee unlearning in the context of digital transformation. For a successful organizational change, employees are willing to be open to new demands, embrace change, proactively adapt their mindsets and cognitive patterns, and accelerate their learning to meet the work challenges of organizational digital change. Notably, when facing dramatic changes during digital transformation, the value of unlearning needs to be emphasized. In the digital era, striking a balance between “learning” and “unlearning” to achieve the iteration and updating of knowledge and skills is essential.

Fourth, this study provides finer-grained knowledge regarding when digital capabilities positively influence employee learning-related behaviors during digital transformation. Communication feedback is an integral part of developmental HRM practice and emphasizes the critical role of organizational improvement and smooth communication feedback mechanisms in empowering employees to learn and unlearn. Thus, it contributes to the HRM literature by providing management direction in the context of digital transformation.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study offers a few takeaway messages for management practices.

First, managers and leaders should invest more in employee learning-related practices during digital transformation. Digital transformation ought to be a mutual combination of soft and hard skills, producing an integration of technical, business, and legal knowledge, with a keen eye for trends, change management skills, and excellent communication skills [78]. Organizations should stress the critical role of employee management in the agenda of putting forward digital transformation. In order to better ensure that employees have adequate knowledge to cope with digital transformation, organizations should encourage learning and unlearning and provide employees with learning opportunities and resources. Specifically, in terms of employee training, it is necessary to help employees establish the mindset of lifelong learning during orientation and continuously strengthen their learning and unlearning skills in subsequent training programs. In terms of collaborative work, organizations should promote excellent departments or members as role models, encourage these best performers to share how to overcome the discomfort in digital transformation, adjust their psychological state, conduct learning better, and impart learning experience. Also, managers and organizations should cultivate “learning organizations” and “unlearning originations” to ensure successful knowledge creation, assimilation, and structure in the future [79].

Second, organizations should devote more efforts to cultivating formal and informal channels to enhance communication feedback, especially with the help of modern information and communication technologies such as digital media and social media platforms [80]. Research has indicated that these digital platforms can promote two-way communication between organizations and employees [80,81] and be used to create and share knowledge, help employees resolve doubts, and acquire cutting-edge knowledge. More importantly, employees are paramount during digital transformation, and an effective communication feedback mechanism per se represents an acknowledgment of people. A newly developed digital working environment means exploration and trial and error for employees. Moreover, in terms of cultural context, Chinese people tend to be more introverted in their social interactions than Westerners, who are more expressive and forthright in their rules of life. Traditional Chinese culture emphasizes “no significant mountain, not dew”, “hide brightness, nourish obscurity”, “look before you leap” and “silence is precious” [82]. This cultural consensus leads to the tendency among Chinese people to keep things to themselves, to shy away from expressing their true feelings, and to keep a low profile even in the face of constructive conflict. Our study shows that it is essential for enterprises to establish internal communication feedback mechanisms during the digital transformation process. For example, companies are encouraged to arrange large regular meetings to share information on the progress of digital transformation, as well as to conduct one-on-one informal communication to synchronize information regarding why digital transformation should be conducted, what will happen after specific digital projects are launched, and what the expectations of leaders are after transformation. In addition, formal and informal channels should be built to collect employees’ suggestions, concerns, and even complaints, and critical leaders should provide specific feedback. Also, in terms of the interaction between leaders and subordinates, leaders can positively communicate with employees, and adopt different modes of expression for different employees, not only for themselves but also to help employees express their ideas and improve work efficiency. When employees encounter challenges, leaders should help them to overcome the discomfort caused by digital transformation. In collaboration, establishing shared documents or e-tools can help employees to solve problems promptly and avoid certain employees being shy and unwilling to ask questions from colleagues or superiors. Also, these e-methods can help employees to reduce the cost of trial and error and improve their learning and performance. Only by establishing an open, inclusive and efficient communication platform and channel can managers reduce employees’ searching costs and improve their learning effectiveness and sustainable performance.

Third, we further advocate that managers should adopt diverse management approaches according to the different backgrounds of employees. During digital transformation, managers should be aware of the diversity of their employees and adopt targeted management methods and strategies. Since there were significant correlations between employee position level and perceived enterprise digital capability (r = 0.11, p < 0.05), employee learning (r = 0.18, p < 0.001), employees unlearning (r = 0.13, p < 0.01), and communication feedback (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), we suggest that different degrees of measures and different types of guidance should be used according to different position levels. For example, compared with the higher-level employees, the front-level employees’ perception of the overall situation regarding digital transformation and their coping strategies was relatively passive. Thus, managers should be more supportive of front-level employees, designate targeted management practices and help them to better carry out learning activities to adapt to the transformation.

Also, since employee educational level is positively related to employee learning (r = 0.13, p < 0.01), different management methods should be adopted for employees with different educational backgrounds. Highly educated employees tend to form unique ways of dealing with knowledge and experience, which is more conducive to coping with learning challenges in the process of organizational change. For employees with higher educational levels, cultivating a learning climate would be beneficial to further encourage them to learn and unlearn. In contrast, for employees with lower educational levels, managers should encourage them to participate in learning, not only by motivating their willingness to learn, but also by providing them with conventional and user-friendly learning materials, and organizing formal and informal training programs, so as to cultivate their habit of active learning. In addition, managers should also pay more attention to employees with a longer tenure. Employee tenure is positively related to perceived enterprise digital capability (r = 0.10, p < 0.05). Such employees might be more aware of the changes brought about by the enterprise digital transformation and are more sensitive to the improvement in enterprise digital capabilities. Also, employee age is positively related to unlearning (r = 0.10, p < 0.05), indicating that elderly employees are vulnerable to the hindrance of old knowledge, experience and behavior. So, it is more urgent for them to carry out unlearning and make a breakthrough in this. By leveraging their experience, and motivating them to unlearn, employees with longer tenure could act as the driving force of digital transformation and set good examples for their colleagues.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

We acknowledge the fact that due to the research conditions, this study inevitably has some limitations, which need to be addressed in future research.

First, this study has certain limitations in studying employee sustainable performance in the context of Chinese culture. According to Hofstadt’s cultural dimension theory, Chinese people tend to have a long-term orientation, pay more attention to the future, and focus on sequential development [77]. Chinese culture emphasizes the values of long-term stability and sustainable development, which can be reflected in employees’ career development and organizational relationships. This cultural concept is fundamental in studying employees’ sustainable performance. The digital transformation of enterprises is a long-term and complex process that cannot be achieved overnight. Employees need to adapt and develop to empower enterprises with digitalization. We call on more scholars to study the sustainable performance of employees in the context of the digital transformation of enterprises in different cultural backgrounds. Thus, it is necessary to pay attention to the applicability of cultural contexts. For the conclusions of this study to be extended to Western culture, data from different cultural backgrounds need to be collected for verification.

Second, since all the data were self-reported, common method bias may contaminate our results. In order to reduce the effect of common method variance, this study adopted a two-wave data collection design with a one-month time interval. At the same time, the single-factor test showed that common method variance was not a serious problem for our results. To further strengthen the validity of the findings, future research is recommended to collect data from multiple sources (e.g., employees, leaders, coworkers, and objective data). Also, future research is encouraged to combine the current research method of questionnaire surveys with interviews, observations, and archival data, and to conduct cross-validation checks of these data sources simultaneously.

Third, definitive causal interferences cannot be drawn using the current survey methodology. In addition, this study lacks longitudinal observation and in-depth analysis of employee learning and unlearning during digital transformation. Digital transformation is a theoretical problem and a long-term dynamic organizational practical problem. If the research conditions permit, future studies are suggested to be combined with interview and observation methods to conduct rich case studies on different stages of digital transformation. In order to strengthen the causal chain of evidence between variables, field experiments are also advocated. Multiple methods should be employed together, providing triangulated evidence to endorse our research findings.

Fourth, we only examine the moderating effect of communication feedback. Future research is encouraged to elaborate more on the boundary conditions exerted by team- and organizational-level-related variables, such as different leadership styles, team climates, and organizational management practices. Moreover, cross-level analytical techniques should be employed to conduct such analyses.

Fifth, there are also certain limitations to collecting data only from Chinese employees when looking at the variable of communication feedback. Compared with employees in Western countries, Chinese employees are more reluctant to express their views frankly or to facilitate communication. This difference may exert influences on the moderating role of the communication feedback mechanism in this study. Thus, validating whether a high level of communication feedback still serves as a moderator in Western culture is necessary. Therefore, we advocate future research to collect data from Western culture and expand the external validity of our proposed relationships.

6. Conclusions

This paper focuses on employee learning and unlearning in the context of enterprise digital transformation and explores how and when enterprise digital transformation exerts impacts on employee sustainable performance. Specifically, this paper examines the mediating effect of employee learning and unlearning, linking perceived enterprise digital capability and employee sustainable performance. Moreover, the moderating role of communication feedback is validated. Our research shows that employee learning and unlearning need to be considered in the context of enterprise digital transformation, since they could fuel the mastery of digital literacy and facilitate the upgrading of outdated paradigms. In addition, establishing a communication feedback channel is conducive to employees gaining feedback promptly and conducting real-time self-correction, in order to better adapt to the new digital job demands and eventually contribute to the successful implementation of enterprise digital transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F. and Q.Z.; methodology, Q.Z.; formal analysis, Q.Z.; investigation, F.F. and Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.F., W.Z. and Q.Z.; supervision, F.F.; project administration, F.F.; funding acquisition, Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 72202012, and the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, grant number 21YJC630178.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Duggan, J.; Sherman, U.; Carbery, R.; McDonnell, A. Algorithmic management and app-work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; de Jonge, J.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Taris, T.W. Employee Sustainable Performance (E-SuPer): Theoretical Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Psychometric Properties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alathamneh, F.; Al-Hawary, S. Impact of digital transformation on sustainable performance. Int. J. Data. Sci. Anal. 2023, 7, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Digital transformation and sustainable performance: The moderating role of market turbulence. Ind. Market Manag. 2022, 104, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, M.M.A.K.; Fan, L.; Islam, M.T.; Uddin, M. The Influence of Knowledge Sharing on Sustainable Performance: A Moderated Mediation Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Heinze, I.; Henschel, T.; Nawaz, N. Unlearning: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2020, 24, 472–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Sting, F.J. Employees’ perspectives on digitalization-induced change: Exploring frames of Industry 4.0. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2020, 6, 406–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.D. Concepts of digital economy and Industry 4.0 in intelligent and information systems. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2021, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruysseveldt, J.; Van Dijke, M. When are workload and workplace learning opportunities related in a curvilinear manner? The moderating role of autonomy. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing Innovation Management Research in a Digital World. MIS Quart. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdi, K.; Allan, C.; Warr, P. Correlates and perceived outcomes of four types of employee development activity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.A.; Soares, H.M.V.M.; Soares, E.V. Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles Trigger Caspase- and Mitochondria-Dependent Apoptosis in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, J.C.; Acedo, F.J.; Barbero, J.L. Learning, unlearning and internationalisation: Evidence from the pre-export phase. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2009, 30, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, B. How Organizations Learn and Unlearn; Oxford University Press: Oxford, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hislop, D.; Bosley, S.; Coombs, C.; Holland, J. The process of individual unlearning: A neglected topic in an under-researched field. Manag. Learn. 2013, 45, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A.E.; Byrne, J.C.; Lynn, G.S.; Keskin, H. New product development in turbulent environments: Impact of improvisation and unlearning on new product performance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2007, 24, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.P.; Chou, C.; Chiu, Y.J. How unlearning affects radical innovation: The dynamics of social capital and slack resources. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2014, 87, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, T.J. Employee learning and development orientation: Toward an integrative model of involvement in continuous learning. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, A.; Boxall, P. Lean production, employee learning and workplace outcomes: A case analysis through the ability-motivation-opportunity framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2013, 23, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzolla, G. Call for papers for special issue: “Digital transformation: What is new if anything?”. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2018, 4, 378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Meske, C.; Junglas, I. Investigating the elicitation of employees’ support towards digital workplace transformation. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2020, 40, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, S.; Hill, N.S.; Gibbs, J.L.; Maruping, L.M. Virtual work: Bridging research clusters. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 308–341. [Google Scholar]

- Markoulli, M.P.; Lee, C.I.; Byington, E.; Felps, W.A. Mapping human resource management: Reviewing the field and charting future directions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 367–396. [Google Scholar]

- Piatnychuk, I.; Boryshkevych, I.; Tomashevska, A.; Hryhoruk, I.; Sala, D. Online Tools in Providing Feedback in Management. J. Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian Natl. Univ. 2022, 9, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Butts, M.M.; Vandenberg, R.J. Effects of management communication, opportunity for learning, and work schedule flexibility on organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, P.; Forslin, J.; Shani, A.B.; Kira, M. Emerging Work Systems: Creating Sustainable Work Systems; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and education. Educ. Forum. 1986, 50, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postman, L.; Stark, K. The role of response set in tests of unlearning. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1965, 4, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrom, P.C.; Starbuck, W.H. To avoid organizational crisis, unlearn. Organ. Dyn. 1984, 12, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, J.; Scholderer, J. Forget unlearning? How an empirically unwarranted concept from psychology was imported to flourish in management and organisation studies. Manag. Learn. 2016, 47, 443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M. Learning and unlearning: A conceptual note. Learn. Organ. 2017, 23, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschl, M. Unlearning towards an uncertain future. On the back end of unlearning. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Park, S. Unlearning in the workplace: Antecedents and outcomes. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2021, 33, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S. Effects of goal orientation and unlearning on individual exploration activities. J. Workplace Learn. 2023, 35, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Effects of the paradox mindset on work engagement: The mediating role of seeking challenges and individual unlearning. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 2708–2718. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Mutuc, E.B.; Su, N.; Hu, T.; Zhou, H.; Fan, C.; Hu, F.; Wei, S. How Does Organizational Unlearning Influence Product Innovation Performance? Moderating Effect of Environmental Dynamism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 840775. [Google Scholar]

- Akdere, M.; Egan, T. Transformational leadership and human resource development: Linking employee learning, job satisfaction, and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2020, 31, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, B.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.; Yoon, S.W. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between learning organization and organizational performance and employee attitudes: Using the dimensions of learning organization questionnaire. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2021, 20, 207–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butschan, J.; Heidenreich, S.; Weber, B.T. Tackling hurdles to digital transformation-the role of competencies for successful industrial internet of things (Iot) implementation. Emscon 2019, 23, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Hyland, P.; Acutt, B. Considering unlearning in HRD practices: An Australian study. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2006, 30, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Rodríguez, A.L.; Eldridge, S.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal-Millán, A.G.; Ortega-Gutiérrez, J. Organizational unlearning, innovation outcomes, and performance: The moderating effect of firm size. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.E.; Fey, C.F. Compatibility and unlearning in knowledge transfer in mergers and acquisitions. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Sánchez-Vidal, M.E.; Cegarra-Leiva, D. Linking unlearning with work-life balance: An initial empirical investigation into SMEs. J. Small. Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, S.M.; Nembhard, D.A.; Uzumeri, M.V. The effects of worker learning, forgetting, and heterogeneity on assembly line productivity. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupi, N. Learning-forgetting-unlearning-relearning-the learning organization’s learning dynamics. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 542–548. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Stylianou, A.; Subramaniam, C.; Niu, Y. Information technology and interorganizational learning: An investigation of knowledge exploration and exploitation processes. Inform. Manag. 2015, 52, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leijen-Zeelenberg, J.E.; van Raak, A.J.; Duimel-Peeters, I.G.; Kroese, M.E.; Brink, P.R.; Ruwaard, D.; Vrijhoef, H.J. Barriers to implementation of a redesign of information transfer and feedback in acute care: Results from a multiple case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveh, E.; Katznavon, T.; Stern, Z. Active learning climate and employee errors: The moderating effects of personality traits. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 6, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglena, S. Good practices and recommendations for success in construction digitalization. TEM J. 2020, 9, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; Sun, J.M.; Jepsen, D.; Zhang, Y. Supervisor negative feedback and employee motivation to learn: An attribution perspective. Hum. Relat. 2021, 7, 310–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1766–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The Wording and Translation of Research Instruments; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.; Waeger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plann. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Digitalization capabilities as enablers of value co-creation in servitizing firms. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Digital technology adoption, digital dynamic capability, and digital transformation performance of textile industry: Moderating role of digital innovation orientation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 2038–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhaber, S.A.; Patel, P.C. How do young firms manage product portfolio complexity? The role of absorptive capacity and ambidexterity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1516–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y. Organizational unlearning and knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A: The roles of routine and knowledge compatibility. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 21, 1580–1595. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Roberts, K.H. Task group structure, communication, and effectiveness in three organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.H.; O’Reilly, C.A. Measuring organizational communication. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablin, F.M.; Putnam, L.L. (Eds.) The New Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendhran, R.; Fast, N.J. Humans judge, algorithms nudge: The psychology of behavior tracking acceptance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 2021, 164, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, T.P. Modern Regression Methods; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fiddell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed.; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]