1. Introduction

Africa does not make significant contributions to global carbon emissions and is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change [

1,

2,

3]. The continent faces a confluence of challenges, including high unemployment rates, widespread poverty, and food insecurity, which exacerbate the effects of climate shocks [

3]. An additional challenge is that industrialization is coupled with greenhouse emissions. A restriction on environmental externalities implies that the gap between developing and developed countries is difficult to close since developed nations industrialized without strict limitations on emissions [

4]. Moreover, Africa has been grappling with limited access to global climate funding. This situation has often left Africa in the cracks of the climate funding architecture, being marginalized and struggling to adapt to and mitigate climate change.

Vulnerability to climate change shocks is a complex phenomenon that comprises both environmental vulnerabilities and socio-economic vulnerabilities [

5,

6]. However, past studies have only concentrated on the physical dimensions of climate vulnerability to the exclusion of the socio-economic dimension [

7]. Africa’s vulnerability to climate change is rooted in its exposure to various climate-related risks, including droughts, floods, desertification, and rising sea levels [

8,

9]. These risks pose severe threats to critical sectors, such as agriculture, water resources, infrastructure, and socio-economic development.

Assessing differences in vulnerability levels across countries can facilitate the identification of unique areas where context-specific efforts can be focused to reduce susceptibility to climate variability [

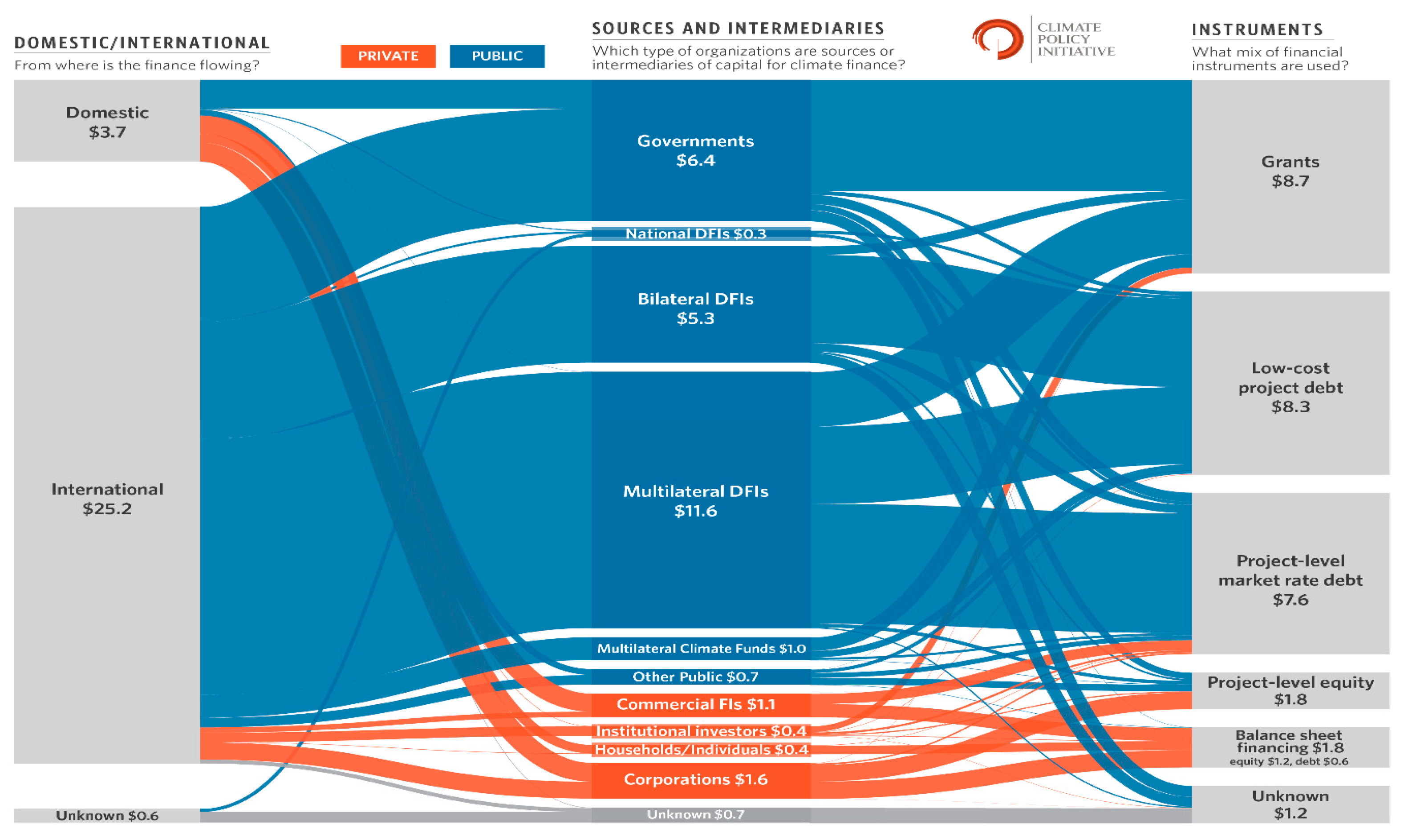

10]. Africa’s representation and access to climate finance are hindered by financial, technical, social, cultural, and systemic barriers and biases [

11,

12]. Climate finance involves the examination of both local and global funding for public and private investments aimed at facilitating the mitigation of and adaptation to climate change [

13]. Historically, the distribution of climate finance has favored developed and emerging economies and regions due to their higher emissions [

14]. However, the financial and technical needs for climate finance greatly exceed the current availability of funds for developing countries [

15]. Limited capacity and resources for project development and implementation, difficulties in accessing international climate funds, and complex bureaucratic processes are some of the challenges that African countries face in effectively channeling climate finance [

16,

17].

However, over the years, there has been recognition of the need to address this imbalance and support vulnerable regions such as Africa [

18]. Leading to the COP 15 in 2009, “Copenhagen Accord” was the specific monetary commitment of USD 10 billion a year from 2010 to 2012, increasing to USD 100 billion by 2020, made by wealthy nations to support developing countries in implementing adaptation and mitigation strategies [

19]. Thereafter, several initiatives were launched to increase climate finance for developing countries, including the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Adaptation Fund, and various bilateral and multilateral initiatives. These mechanisms aim to provide financial resources to support climate change adaptation and mitigation projects in developing countries, including those in Africa. In addition to global climate funds, scholars have also explored the potential of the digital finance and digital economy in unlocking the green energy transition of countries [

20,

21,

22]. The authors showed that digital financial services have a negative correlation with carbon emission in the long run and can leverage inclusivity in finance for adaptation and mitigating strategies [

23].

That said, challenges persist in effectively channeling climate finance to African countries. Some key challenges include limited institutional capacity [

24], limited resources for project development and implementation, difficulties in accessing international climate funds, and complex bureaucratic processes. Additionally, developing countries often face stringent requirements, which can make it challenging to access the necessary climate finances [

25]. In order to make an assessment of the barriers of Africa’s access to climate finance and the potential solutions, this study carried out a bibliometric review addressing the following questions:

- (1)

What is the aggregate production and distribution pattern of climate finance studies in the context of Africa as reflected through publication trends, countries of publication, and most productive journals?

- (2)

Which articles and authors have wielded a pronounced impact on the domain of climate finance research in Africa, predicated upon citation metrics?

- (3)

What are the country collaborations within the purview of climate finance literature?

- (4)

What are the emerging themes based on the content analysis of the extant literature in climate finance research, and what recommendations and future research directions can be drawn?

A bibliometric analysis provides a quantifiable evaluation of research excellence and its output, spanning diverse chronological periods, research domains, prominent nations, and other dimensions [

26,

27,

28]. The application of this methodology aids in the detection of research patterns and the evolutionary trajectory within a specific research domain. It further illuminates the influence exerted by research publications, identifies influential authors, and highlights frequently cited works [

26,

27].

The main contributions of the paper are as follows: The study undertook a comprehensive exploration of the systemic barriers and biases that hinder Africa’s access to climate finance, thereby leaving the continent at a disadvantage in addressing the effects of climate change. While previous research has acknowledged the vulnerability of Africa to climate change, this study delved deeper into the underlying issues related to climate finance. Moreover, the study conducted a bibliometric review and analyzed the publication trends, leading authors, most influential articles, journals, and countries. Moreover, the study showed the emerging themes and solutions to promote a more equitable and inclusive approach to climate finance, emphasizing the need to redefine climate vulnerability and revamp the climate finance landscape.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the contextual background, and

Section 3 presents the methodology employed in conducting the study.

Section 4 provides the results and analysis of the study.

Section 5 presents the discussions of the paper based on the content analysis of the extant studies, and

Section 6 concludes the study.

4. Results and Analysis

Table 4 presents information about the data obtained from Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases, as well as the merged data from both sources. The data span from 2007 to 2023 and encompass various types of documents, such as articles, book chapters, conference papers, editorial reviews, and letters. While the Scopus database presented records spanning from 2010 to 2023, the WoS database contained records from 2007 to 2023. The merging of datasets from these two databases offers the distinct advantage of covering a longer time span, ranging from 2007 to 2023. This extended time coverage enhances the comprehensiveness and depth of the dataset, providing a more robust foundation for analyzing trends and patterns related to the research topic.

4.1. Summary of Bibliometric Data

Considering the number of documents, WoS contained 91 documents, while Scopus included 94. The merged dataset combined both sets, resulting in a total of 139 documents available for analysis. Furthermore, WoS exhibited a growth rate of 10.58%, indicating a steady increase in document publications over time. Scopus, on the other hand, presented a slightly higher growth rate at 13.18%. The merged dataset shown in

Table 4 had a growth rate of 13.88%, which suggests a consistent rise in document contributions overtime. There is a notable jump in the number of publications from 2019 to 2023, and this may be attributed to the rise in discussions and importance of climate change agenda in recent years.

Additionally, the metric of co-authors per document sheds light on the collaborative nature of research efforts. The average co-authors per document stood at approximately 3.71 for WoS, 3.34 for Scopus, and 3.47 for the merged dataset. Moreover, international co-authorships offer insights into the extent of global collaboration within the datasets. WoS recorded a percentage of 37.76% for international co-authorships, while Scopus reflected a slightly lower figure at 28.7%. The merged dataset maintained a significant level of international collaboration at 26.62%. This shows that there are rising global efforts and collaboration between scholars in the field of climate finance.

4.2. Annual Scientific Production

As depicted by

Table 5, the distribution of articles over the years revealed an increasing trend from 2007 to 2023. The years 2007, 2010, and 2011 saw a relatively lower number of articles, suggesting a gradual initiation of research interest in climate finance within the context of African countries. There was a notable surge in the number of articles in 2012, indicating a growing focus on the topic. The trend fluctuated and reached its peak in 2022 with 26 articles. This surge could be attributed to several factors, including growing relevance of climate finance, transition to green economy, and policy developments.

4.3. Top 10 Most Prolific Authors

Table 6 showcases the top 10 most productive authors in the field of climate finance in the context of African countries. The authors were ranked based on the number of articles attributed to them and their respective fractionalized ranks. Chirambo D emerges as the most prolific author, leading the list with 11 articles and thereby securing the top rank. Doku I follows with six articles, obtaining the second rank. Phiri A holds the third position with four articles, although their fractionalized rank of 2.00 indicated a competitive presence. Dougill A is in fourth place with three articles.

Ncwadi R and Stringer L are in the fifth and sixth positions, respectively, with each contributing three articles. Ahenkan A and Amadu F, both with two articles, are listed seventh and eighth, respectively. Besson S and Cull T close the list in the ninth and tenth positions, each credited with two articles.

4.4. Most Influential Articles

Table 7 presents the top 10 notable research publications in the field of climate finance, along with details regarding the authors, publication years, journals, total citations (TC), average citations per year (TC/year), normalized total citations (NTC), and corresponding ranks.

As illustrated in

Table 7, Muller M (2007) [

88] published an article titled “Adapting to climate change: water management for urban resilience” in

Environment and Urbanization. The article highlighted that the allocation of supplementary funds is based on the “polluter pays” principle, advocating for these funds to be integrated into government budgets instead of being exclusively earmarked within distinct climate finance mechanisms. The article had 128 total citations and an average of 7.53 citations per year, securing the top rank position. The second position was occupied by an article written by Schwerhoff G (2017) [

89]. The article was published in

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. The article is titled “Financing renewable energy in Africa—Key challenge of the sustainable development goals”, and it accumulated 115 total citations and an average of 16.43 citations per year. The article highlighted that governance practices need to be enhanced with the aim of attaining an enhanced credit rating, thereby leading to a reduction in financing costs.

4.5. Research Output by Country

Table 8 shows the top 10 most productive countries based on their total citations in the context of climate finance in Africa. Germany holds the first position with a total of 496 citations, showcasing its strong contribution to the field. The United Kingdom secures the second position with 311 citations. The USA stand in the third position with 274 citations. The positions of Germany, the United Kingdom, and the USA in the top three could be attributed to the availability of research funds and expertise in the field of climate finance, as well as strong scientific collaborations on research projects.

At the bottom four of the top 10 most productive countries there are mostly African countries, namely Ghana, Kenya, and Congo. This could be due to limited research infrastructure and funding resources dedicated to climate finance and green transition, leading to limited research output.

4.6. Most Productive Sources

As illustrated in

Table 9,

Climate Policy is the leading source, and it has published eight articles, indicating its significant role in disseminating research related to policies and strategies addressing climate change and finance in Africa. The second position is occupied by

Climate and Development, which published six articles and contributed to research that explores the nexus of climate change and sustainable development, including climate finance. The last two positions are occupied by

African Handbook Of Climate Change Adaptation and

Climate Change Management both with 2 publications each.

4.7. Bibliometric Coupling of Countries

Figure 4 illustrates the bibliometric coupling analysis of countries, with circles representing nodes and lines indicating collaborations among these countries. The size of each node reflects the respective country’s impact and influence in the domain of climate finance research in Africa. Larger nodes indicate greater influence within the field. Nodes of similar color denote countries belonging to the same research cluster.

Germany possesses the largest node, signifying its prominent position as a leading country with substantial impact and influence in the field. Collaborative research ties are evident through connecting lines to Japan, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Austria. Conversely, countries with smaller nodes, such as Nigeria, Ghana, and Ethiopia, exhibit comparatively minimal research influence and impact in the domain.

Regarding African countries, South Africa stands out with the most significant influence and impact in the field, reflected by its larger node size. Additionally, South Africa’s extensive collaborations with other nations beyond the African continent underscore its role as a key contributor to global climate finance research efforts. This could be attributed to the fact that South Africa is one of the largest emitters in Africa, and it continues to seek climate adaptation finance in order to facilitate its transition to a green economy characterized by zero carbon emissions.

4.8. Co-Occurrence of Keywords

Figure 5 shows a visual representation of the co-occurrence of “Keywords” terms. A co-occurrence analysis examines the frequency of keyword occurrences in analyzed documents to evaluate their relationships. The size of each node in the visualization, determined by its diameter, corresponds to the number of articles featuring the respective term, indicating its frequency of appearance. The proximity of keywords within the visualization indicates the extent of their interconnectedness or relatedness.

Figure 5 depicts that the keywords “Climate Change” and “Climate Finance” stand out as the most frequently utilized terms, represented by their large node size compared to others. Climate Finance is frequently associated with other terms, such as “renewable energy”, “energy policy”, “private sector”, “sustainable development”, “financial services”, “alternative energy”, and “energy access”. This indicates that researchers focus on understanding the implications for climate finance for energy access and sustainable development in Africa. The color coding of nodes in

Figure 5 reveals that there are five clusters of keywords nodes. Based on the keyword co-occurrence, the study identified the following emerging themes in the literature (see

Table 10): (i) exploring renewable energy, policies, and investments for a sustainable energy transition; (ii) climate change resilience and smart agriculture: navigating adaptation and the mitigation finance landscape; (iii) enhancing sustainable development through capacity building, governance, and informed decision making; (iv) advancing climate change mitigation and emission reduction in the developing world: policy implications under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; (v) the role of microfinance in achieving sustainable development and financial inclusion for entrepreneurs in climate change adaptation.

5. Discussion

Africa’s active participation in global climate action is essential for addressing the continent’s unique vulnerabilities and promoting a sustainable future. Based on the content analysis of the extant studies, this study discussed the following key aspects;

- (1)

Redefining climate vulnerability;

- (2)

Exploring financing mechanisms to improve access and distribution of climate finance in Africa

- (a)

Scaling up concessional finance, a vital step towards building regional resilience;

- (b)

Harnessing the untapped potential of climate funds as a crucial funding source for climate mitigation and adaptation in Africa;

- (c)

Mobilizing pension funds as a strategic source of investments for climate action;

- (3)

Mobilizing political will and commitment;

- (4)

Addressing low sovereign credit ratings and the de-risking of projects in Africa;

- (5)

Gendered climate finance and investment;

- (6)

Strengthening domestic resource mobilization;

- (7)

Coordinating and harmonizing climate finance mechanisms.

5.1. Redefining Climate Vulnerability

To date, there is no consensus on the definition of vulnerability to climate change [

94]. However, scholars agree that it consists of physical exposure and sensitivity to natural hazards and adaptive capacity [

95]. To ensure that Africa receives adequate support to tackle climate change, it is necessary to redefine climate vulnerability and revamp the existing climate finance landscape. Identifying countries that are vulnerable to climate change requires political and normative decisions that are hard to capture with quantitative indicators [

96]. This would involve considering additional criteria that reflect the unique vulnerabilities of African countries, such as climate-related risks, geographic vulnerability, and socio-economic indicators.

Redefining vulnerability would enable a fairer distribution of climate finance to African nations. Policymakers face the challenge of operationalizing vulnerability, which is further complicated by the lack of a scientific consensus on conceptually defining and measuring it [

97,

98].

There are three primary indices widely recognized for measuring and ranking countries’ vulnerability to climate change. Firstly, the ND-GAIN (Global Adaptation Index), developed by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative, assesses vulnerability through a comprehensive set of indicators, encompassing exposure to climate hazards, sensitivity to climate impacts, and adaptive capacity at the country or regional level. Notably, among the top ten most vulnerable nations worldwide, eight are located in sub-Saharan Africa, as indicated by ND-GAIN [

99]. Secondly, there is the INFORM index INFORM, [

100] and thirdly, there is the World Risk Index World Risk Report [

101]. It is worth noting that these indices may yield slightly divergent rankings for countries.

Based on the aforementioned indices, a limited body of research has previously aimed to track international adaptation finance and examine the extent to which bilateral, multilateral, and fund-based adaptation finance are aligned with the vulnerability of recipient countries [

51]. Studies focusing specifically on bilateral adaptation finance have indicated that donors do consider vulnerability when allocating funds for adaptation purposes [

102]. However, an examination of the variables used to measure vulnerability revealed that physical vulnerability or exposure appear to have a greater influence than factors related to socio-economic vulnerability [

98,

102,

103].

Against the above background, redefining climate vulnerability and reaching a consensus are crucial to address the disparities faced by African nations in accessing climate finance [

103]. A comprehensive and context-specific approach is needed, considering factors such as food insecurity, water scarcity, ecosystem fragility, and social vulnerability [

104]. By broadening the definition of vulnerability and mapping vulnerability to multiple stressors, African nations can receive a fairer share of climate finance and better address their specific challenges [

105].

Against the above background, this review study argues that the following aspects need to be taken into consideration when re-defining climate vulnerability in African countries:

- i

Ecosystem fragility: The diverse African ecosystems offer vital services to nearby communities, such as food, water, and livelihoods. The fragility and resilience of ecosystems, such as forests, wetlands, and coastal areas, which are essential for maintaining biodiversity, regulating the climate, and providing ecosystem services, should be taken into consideration when assessing vulnerability [

106].

- ii

Exposure to climate-related hazards: As indicated before, Africa is significantly exposed to a variety of climate-related problems. Any vulnerability assessment should focus on this exposure. When assessing vulnerability, one should take into account elements such as flood frequency and intensity, sea-level rise projections, and temperature extremes [

107].

- iii

Reliance on rain-fed agriculture: Many African countries heavily rely on rain-fed agriculture, making them particularly vulnerable to climate change and fluctuation. Analyzing the reliance on agriculture, the accessibility of irrigation systems, the availability of agricultural supplies, and the ability to modify farming operations in response to shifting climatic conditions are all important components of assessing susceptibility [

41].

- iv

Social vulnerability and governance: Social factors have a big impact on climate change vulnerability. The ability of communities to deal with and adapt to issues associated with climate change is influenced by factors such as poverty, inequality, access to healthcare and education, social cohesiveness, and governance systems. Indicators of social vulnerability, such as demographic traits, social cohesion, and government efficiency, should be taken into account when assessing vulnerability [

108].

- v

Water shortage and access: Lack of access to clean water is a serious problem in Africa, which is made worse by climate change. Water resource availability and quality should be taken into account when assessing vulnerability, as well as the ability to manage water shortages through infrastructure, water-saving techniques, and effective water allocation mechanisms [

109].

Moreover, to ensure equitable participation and avoid leaving behind countries with limited institutional capacity and high vulnerability, it is essential for funds to enhance their existing mechanisms. This includes strengthening the emerging simplified approval track, which would enable the inclusion of countries facing significant challenges. It is crucial to prioritize the needs of these countries and their populations in the long run, as emphasized in the studies by [

7,

45].

The international community can better appreciate the distinct difficulties faced by African nations by adopting a more thorough and context-specific approach to measuring vulnerability. To address the unique needs and to promote resilience in these countries, specialized interventions, policies, and support structures can be based on this understanding. It is essential for policymakers, academics, local communities, and international organizations to work together to ensure that vulnerability assessments accurately reflect the multifaceted and unique character of climate vulnerability in Africa.

5.2. Exploring Financing Mechanisms to Improve Access and Distribution of Climate Finance in Africa

Leveraging private sector investments, climate bonds, insurance mechanisms, and partnerships with international financial institutions can help bridge the gap and ensure funds reach those who need them the most.

Efforts should be made to increase the overall funding available for climate finance and ensure a more equitable distribution across regions. Developed countries and international institutions should fulfill their commitments to mobilize USD 100 billion annually by 2020 to support climate action in developing countries, as pledged under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [

110].

To improve the scalability of projects and ensure stable funding, African countries need to diversify financial instruments, shifting focus from grants to loans and private capital. This strategic shift will enhance the predictability of funds and enable sustainable funding mechanisms for ambitious projects in the region [

60].

5.2.1. Scaling Up Concessional Finance: A Vital Step towards Building Regional Resilience

Concessional climate finance should be considered as additional funding, complementing existing development aid flows instead of competing and substituting them [

111]. It is worth emphasizing that concessional finance for African countries should be targeted at projects that will add value not only to the environment, but also to the economy and society, such as investments in infrastructure to produce energy that most sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries desperately need to transform their economies and increase productivity. Climate financial intermediary funds (FIFs) stand as significant reservoirs of multilateral grants and concessional finance specifically designated for climate-related purposes, encompassing middle-income countries (MICs) as beneficiaries [

112].

5.2.2. Harnessing the Untapped Potential of Climate Funds as a Crucial Funding Source for Climate Mitigation and Adaptation in Africa

Climate funds, although they play a valuable role in supporting climate goals, constitute only a small portion of sub-Saharan Africa’s overall climate finance landscape. Donors perceive these funds as convenient and specialized funds for channeling assistance specifically for climate-related objectives. The financing for climate funds is typically sourced from bilateral donors or multilateral financial institutions, which are then allocated to various recipients, such as governments, national development banks, (non-governmental organizations) NGOs, and the private sector.

It is worth highlighting that climate funds have resulted in a surplus, with disbursements falling short of the funds received. The overall deposits in global climate funds have reached USD 35 billion, following initial pledges of USD 43 billion [

111]. However, actual disbursements has been less than USD 11 billion [

111].

Collaborative capacity-building efforts are essential to equip individuals with the skills necessary to develop projects that are likely to secure funding from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and from the CFU [

113]. This capacity building should involve close cooperation with the funds themselves, local universities, and relevant government departments. It is crucial to ensure that the funds are directed towards the right destinations, as highlighted in the preceding section on the rise in concessional funding. Therefore, the projects should: (a) align with the country’s key priorities, as outlined in the national development plan and vision document; (b) concentrate on infrastructure development to enhance economic productivity and foster competition in strategic sectors of the economy; (c) incorporate independent civil society representation, including the presence of a free press, in committees responsible for monitoring and evaluating budget allocations and fund utilization. This inclusion will fortify transparency and accountability mechanisms.

5.2.3. Mobilizing Pension Funds as Strategic Source of Investments for Climate Action

Engaging pension funds in climate finance and investment through suitable financial instruments is crucial. The key challenge is that, traditionally, pension funds have a low risk appetite due to liquidity requirements. While some North African countries have achieved a pension coverage rate of approximately 80%, sub-Saharan Africa still has a relatively low coverage rate of around 10%. Pension funds are particularly robust in South Africa and Botswana. The total assets under management in 12 emerging markets in Africa amount to nearly USD 400 billion. According to reports, it was anticipated that the assets under management of African pension funds would increase to approximately USD 1.1 trillion by 2020. The vehicle for green investing for climate change adaptation and mitigation includes green bonds, structured green products, and green infrastructure funds.

5.3. The Importance of Political Will and Commitment

Political will plays a crucial role in addressing the challenges faced by African countries in accessing climate finance [

114]. Commitment to the pace of change and the realignment of financial flows towards low-emission and climate-resilient investments is necessary. Political will is a critical determinant of the success or failure of environmental policies and interventions [

115]. This requires collective efforts from governments, international institutions, and stakeholders to ensure that Africa receives adequate support to tackle climate change and build climate resilience. For example, South Africa is amongst the few African countries with a climate change bill (B9-2022) introduced in February 2022 by the Minister of Forestry, Fisheries, and Environment to encourage low carbon transition and climate resilience.

5.4. Africa’s Credit Rating and De-Risking Projects

Countries in Africa have lower sovereign credit ratings that make it difficult for them to access climate finance [

116]. Climate change vulnerability has adverse effects on sovereign credit ratings, even after taking into account conventional macroeconomic determinants of sovereign bond spreads and credit worthiness [

117]. Improving the resilience of African countries to climate change can reduce the likelihood of sovereign debt default and improve capital flows to mitigation and adaptation projects, especially renewable energy [

118]. Other challenges of climate finance in Africa include the lack of collateral, significant initial capital requirements for investment projects, and uncertain long-term horizons for infrastructure initiatives. Moreover, obvious risks associated with climate capital flows to African countries include currency risk, regulatory and political risk, business-related risk, and technical risks. These risks introduce uncertainties and potential negative outcomes that can discourage investors or alter expected returns. Multilateral development banks should prioritize the financial de-risking of investment projects within African countries as a strategy to unlock the vast renewable energy potential present in the African region [

87,

119,

120].

5.5. Gendered Climate Finance and Investment

There are several advantages in bridging the gender gap within the energy sector, including a wider availability of the skilled labor workforce. Some academic studies suggest that women as corporate leaders may tend to be more balanced in their ambition vis-à-vis the environmental consequences [

121,

122]. Furthermore, the African Development Bank has shown that about 90% of the informal labor force constitutes women who are mostly engaged in agricultural activities. However, the informal sector remains largely uninsured from climate risks, and this makes women more prone to climate change shocks since the agricultural sector is one of the hardest hit by climate hazards. This requires innovation on gendered financial instruments, which will channel adaptation funding to women-owned projects across susceptible sectors, especially agriculture [

123,

124].

5.6. Strengthening Domestic Resource Mobilization

Promoting sustainable and inclusive economic growth, enhancing governance frameworks, and fostering partnerships between governments, the private sector, and civil society organizations are crucial for strengthening domestic resource mobilization in African countries. By mobilizing and raising funds domestically through carbon taxes on most emitting sectors, countries can raise adaptation funds.

Building local capacity in African countries to access, manage, and utilize climate finance effectively is essential. This involves promoting sustainable and inclusive economic growth, enhancing governance frameworks, and fostering partnerships between governments, the private sector, and civil society organizations. By strengthening domestic resource mobilization, African countries can become more resilient to climate change and can reduce their dependence on external funding.

5.7. Coordinating and Harmonizing Climate Finance Mechanisms

Fragmented governance characterizes the management of climate finance for mitigation and adaptation in developing countries, both at the international and national levels. Fragmented governance refers to the decentralized and disjointed management of public climate finance for mitigation and adaptation in developing countries, both at the international and national levels. This fragmentation is characterized by the involvement of numerous actors with overlapping mandates, preferences, and areas of expertise in climate finance [

125].

To address the challenges posed by this fragmentation, coordination among these actors has emerged as a necessary approach. The authors in [

60] highlighted the importance of harmonization and raised a crucial question: What distinguishes the operations of the Global Climate Fund from the existing climate funds that provide financial resources for climate change activities in Africa?

The coordination and harmonization of climate funds are essential to tackle the complexity and inefficiencies in the climate finance architecture. This requires closer engagement between the secretariats and governing bodies of these funds to minimize the duplication of efforts and streamline processes. By harmonizing fund requirements, application procedures can be simplified and consistent standards for accessing funds can be established. Furthermore, enhancing coordination and harmonization allows for a clearer division of labor and specialization among funds. This means that different funds can focus on supporting specific thematic areas, project sizes, and risk levels, effectively addressing gaps and overlaps in climate finance support.

Overall, by promoting coordination, harmonization, and specialization among climate funds, the management of public climate finance can become more efficient, streamlined, and effective in supporting mitigation and adaptation efforts in developing countries.

6. Conclusions

Africa faces significant challenges in accessing climate finance and addressing climate vulnerability. This study carried out a bibliometric analysis to determine the publication trends, productive authors, journals, and country collaborations. Moreover, the study showcased leading articles in the field of climate finance in Africa, as well as the emerging themes. Finally, the study unearthed and discussed critical topics from the content analysis of the extant literature. The study combined bibliometric data retrieved from the Scopus and Web of Sciences databases.

Web of Science (WoS) contained 91 documents, while Scopus included 94. Merging these datasets resulted in a total of 139 documents available for analysis. WoS showed a growth rate of 10.58%, while Scopus exhibited a slightly higher rate of 13.18%. The merged dataset had a growth rate of 13.88%, indicating a consistent rise in document contributions over time. There was a significant increase in publications from 2019 to 2023, possibly due to the growing importance of climate change discussions. Moreover, international collaboration was evident, with WoS recording 37.76% for international co-authorships, Scopus recording 28.7%, and the merged dataset recording 26.62%. This suggests increased global collaboration among scholars in the field of climate finance.

Leading authors were identified based on their published documents and fractionalization. Chirambo D ranks first with 11 articles, followed by Doku I with 6. The leading article based on the number of citations is by Muller M published in 2007, and the article is titled “Adapting to climate change: water management for urban resilience”. It discusses the allocation of funds based on the “polluter pays” principle, suggesting the integration of renewable energy costs into government budgets. The second-most influential article was published by Schwerhoff G in 2017. The article is titled “Financing renewable energy in Africa—Key challenge of the sustainable development goals”, and it accumulated 115 citations and focused on renewable energy financing.

Germany is the leading productive country and it holds the top position with 496 citations, followed by the United Kingdom with 311 citations, and the USA with 274 citations, reflecting their strong contributions to the field of climate finance in African countries. These countries likely benefit from research funding, expertise, and scientific collaborations. The top sources are Climate Policy with eight articles and Climate and Development with six, highlighting their leading roles in publishing and disseminating climate finance research.

Through keyword co-occurrence analysis, this study unveiled several emerging themes within the climate finance literature. These themes shed light on various dimensions of research in the field. The first theme delves into research exploring the dynamics of renewable energy, policy frameworks, and investments, with the ultimate goal of facilitating a smooth transition towards sustainable energy sources. The second theme focuses on the intricate relationship between climate change resilience, smart agricultural practices, and the complex financial landscape of adaptation and mitigation efforts. The third theme revolves around the pursuit of sustainable development through capacity building, effective governance, and informed decision-making processes. The fourth theme addresses the critical challenge of advancing climate change mitigation efforts and emission reduction strategies in developing nations, with a specific focus on policy implications guided by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The fifth theme highlights the crucial role of microfinance in facilitating sustainable development and financial inclusion, particularly for entrepreneurs seeking to adapt to the impacts of climate change. Future research, both qualitative and quantitative, must endeavor to explore these themes further.