Sustainable Assessment of the Environmental Activities of Major Cosmetics and Personal Care Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

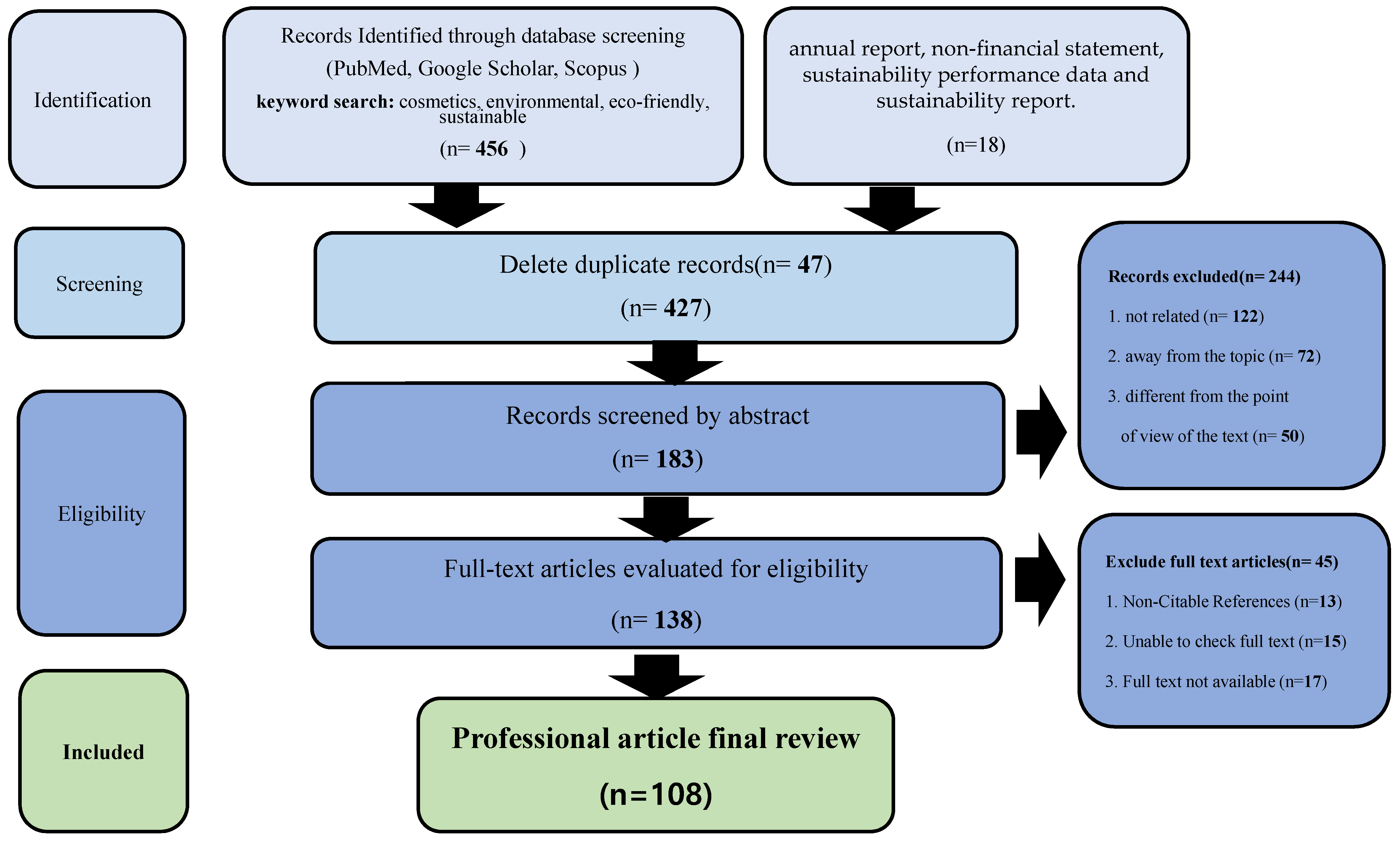

2.1. Material Identification, Screening, Eligibility, Included

2.1.1. Materials Identification

2.1.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.3. Screening and Data Extraction

2.1.4. Study Included and Data Extraction

2.2. Assessment of Companies’ Environmental Activities

2.2.1. Assessment Companies

2.2.2. Environmental Activity Assessment Items

3. Results

3.1. Each Company’s Main Environmental Issues

3.2. Corporate Goals and Bases for the Environment Issue

3.3. Transparency of Environmental Activities

3.4. Objective Certification through Third-Party Organizations

4. Discussions

4.1. Expansion of Company Scope and Need for Active Activities

4.2. Major Roles of Brands, OEM/ODM, and Retailers

4.3. The Importance of Authenticity, Transparency, and Objectivity

4.4. Need to Introduce Common Environment Management Framework

4.5. Encourage Consumers to Buy Eco-Friendly Products

4.6. Government Intervention

4.7. The Novelty, Its Practical/Theoretical/Methodological Contribution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poortvliet, P.M.; Niles, M.T.; Veraart, J.A.; Werners, S.E.; Korporaal, F.C.; Mulder, B.C. Communicating climate change risk: A content analysis of IPCC’s summary for policymakers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace-Wells, D. The uninhabitable earth. In The Best American Magazine Writing 2018; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 271–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kitenest. How Do Cosmetics Impact the Environment? 4 February 2022. Available online: https://kitenest.co.uk/blogs/news/how-do-cosmetics-impact-the-environment (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Acerbi, F.; Rocca, R.; Fumagalli, L.; Taisch, M. Enhancing the cosmetics industry sustainability through a renewed sustainable supplier selection model. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2023, 11, 2161021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimova, T.; Ram, M.; Bogdanov, D.; Fasihi, M.; Khalili, S.; Gulagi, A.; Karjunen, H.; Mensah, T.N.O.; Breyer, C. Global demand analysis for carbon dioxide as raw material from key industrial sources and direct air capture to produce renew-able electricity-based fuels and chemicals. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glew, D.; Lovett, P.N. Life cycle analysis of shea butter use in cosmetics: From parklands to product, low carbon opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 68, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourian, A.; Abba, M.K.; Nasr, G.G. Measurements and analysis of non-methane VOC (NMVOC) emissions from major domestic aerosol sprays at “source”. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGK. How Clean Beauty Can Drive Sustainability in the Beauty Industry. Available online: https://sgkinc.com/en/insights/single-insight/how-clean-beauty-can-drive-sustainability-in-the-b/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Gatt, I.J.; Refalo, P. Reusability and recyclability of plastic cosmetic packaging: A life cycle assessment. Resources. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment Programme. Plastics in Cosmetics: Are We Polluting the Environment through Our Personal Care (Factsheet). Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/plastics-cosmetics-are-we-polluting-environment-through-our-personal-care (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Cinelli, P.; Coltelli, M.B.; Signori, F.; Morganti, P.; Lazzeri, A. Cosmetic packaging to save the environment: Future perspectives. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.D.; Hamam, Y.; Sadiku, E.R.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Kupolati, W.K.; Jamiru, T.; Eze, A.A.; Snyman, J. Need for Sustainable Packaging: An Overview. Polymers 2022, 14, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetics Business. Blue Gold: Water in Cosmetics. 2019. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsbusiness.com/news/article_page/Blue_gold_Water_in_cosmetics/156328 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Aguiar, J.B.; Martins, A.M.; Almeida, C.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. Water sustainability: A waterless life cycle for cosmetic products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, R.C.; Liang, J.; Velichevskaya, A.; Zhou, M. Sustainable palm oil may not be so sustainable. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, A. Impacts of Cosmetic Ingredients on Larval Barnacles: A Study & Discussion of How Cosmetic Ingredients Affect Marine Life; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/18394/Boden_Alexandra_MP_Final.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Sharifan, H. Alarming the impacts of the organic and inorganic UV blockers on endangered coral’s species in the Persian Gulf: A scientific concern for coral protection. Sustain. Future 2020, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.B.; Pawlowski, S.; Kellermann, M.Y.; Petersen-Thiery, M.; Moeller, M.; Nietzer, S.; Schupp, P.J. Toxic effects of UV filters from sunscreens on coral reefs revisited: Regulatory aspects for “reef safe” products. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. What Is Toxicology? Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/science/toxicology/index.cfm (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Bilal, M.; Mehmood, S.; Iqbal, H.M. The beast of beauty: Environmental and health concerns of toxic components in cosmetics. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheele, A.; Sutter, K.; Karatum, O.; Danley-Thomson, A.A.; Redfern, L.K. Environmental impacts of the ultraviolet filter oxybenzone. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawash, H.B.; Moneer, A.A.; Galhoum, A.A.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Mohamed, W.A.; Samy, M.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Gaballah, M.S.; Mubarak, M.F.; Attia, N.F. Occurrence and spatial distribution of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in the aquatic environment, their characteristics, and adopted legislations. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 52, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendall, L.S.; Sewell, M.A. Contributing to marine pollution by washing your face: Microplastics in facial cleansers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Shim, W.J.; Han, G.M.; Cho, Y.; Hong, S.H. Plastic debris as a mobile source of additive chemicals in marine environments: In-situ evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency. ECHA’s Proposed Restriction. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/hot-topics/microplastics (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Beiersdorf. Sustainability Highlight Report 2022. Available online: https://www.beiersdorf.com/sustainability/reporting/sustainability-reporting (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Cosmax. Cosmax Sustainability Report 2022; Cosmax: Seongnam, South Korea, 2022. pp. 27, 63–113. Available online: https://www.cosmax.com/new/download/2022_COSMAX_Sustainability_Report.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Morganti, P.; Morganti, G.; Coltelli, M.B. Skin and Pollution: The smart nano-based cosmeceutical-tissues to save the planet’s ecosystem. In Nanocosmetics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- Blessy, A.; John Paul, J.; Gautam, S.; Jasmin Shany, V.; Sreenath, M. IoT-based air quality monitoring in hair salons: Screening of hazardous air pollutants based on personal exposure and health risk assessment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.R.; Ghim, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Ryu, J.; Shim, I.K.; Lee, J. Volatile Organic Compounds in Under-ground Shopping Districts in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rádis-Baptista, G. Do Synthetic Fragrances in Personal Care and Household Products Impact Indoor Air Quality and Pose Health Risks? J. Xenobiotics 2023, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, J.; Aylwin, J.; Estripeau, R.; Cleary, O.; BCG. Winning the Consumer with Sustainability: Short-Term Imperative. Long-Term Opportunity. 7 June 2022. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/uk-consumer-interest-in-sustainability (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Baratta, A.; Cimino, A.; Longo, F.; Solina, V.; Verteramo, S. The impact of ESG practices in industry with a focus on carbon emissions: Insights and future perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa Khan, N.J.; Mohd Ali, H. Regulations on Non-Financial Disclosure in Corporate Reporting: A Thematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Can the innovation in sustainability disclosures reflect organisational sustainable development? An integrated reporting perspective from China. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1668–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demastus, J.; Landrum, N.E. Organizational sustainability schemes align with weak sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jeong, G.Y. The effect of corporate social responsibility compatibility and authenticity on brand trust and corporate sustainability management: For Korean cosmetics companies. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 895823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, I.; Nicolescu, L.; Ștefan, S.C.; Popa, Ș.C. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Consumer Behaviour in Online Commerce: The Case of Cosmetics during the COVID-19 Pandemics. Electronics 2022, 11, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, M. CSR as a Shield: Unveiling the Power of Different Types of Corporate Social Responsibility during an Organizational Crisis in Safeguarding Company Reputation, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Loyalty. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kolling, C.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Morea, D.; Iazzolino, G. Corporate social responsibility and circular economy from the perspective of consumers: A cross-cultural analysis in the cosmetic industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grădinaru, C.; Obadă, D.R.; Grădinaru, I.A.; Dabija, D.C. Enhancing Sustainable Cosmetics Brand Purchase: A Comprehensive Approach Based on the SOR Model and the Triple Bottom Line. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Chaiyapruk, P.; Faez, S.; Wong, W.K. Generation Y’s sustainable purchasing intention of green personal care products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.L.; Lanero, A.; García, J.A.; Moraño, X. Segmentation of consumers based on awareness, attitudes and use of sustainability labels in the purchase of commonly used products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, S.; Pinto, C.; Cravo, S.; Rocha e Silva, J.; Afonso, C.; Sousa Lobo, J.M.; Tiritan, M.E.; Cidade, H.; Almeida, I.F. Quercus suber: A promising sustainable raw material for cosmetic application. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Moroney, M.S.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Anastas, P.T.; Thompson, E.; Scott, P.; McKeever-Alfieri, M.-A.; Cavanaugh, P.F.; Daher, G. Applying green chemistry to raw material selection and product formulation at The Estée Lauder Companies. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 2397–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaestner, L.; Scope, C.; Neumann, N.; Woelfel, C. Sustainable circular packaging design: A systematic literature review on strategies and applications in the cosmetics industry. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 3265–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.; Hoque, M.E.; Mahbub, T. Biopolymers for sustainable packaging in food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. In Advanced Processing, Properties, and Applications of Starch and Other Bio-Based Polymers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, R.; Acerbi, F.; Fumagalli, L.; Taisch, M. Sustainability paradigm in the cosmetics industry: State of the art. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, S.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. Sustainability calculator: A tool to assess sustainability in cosmetic products. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas, A.L.V.; Bianchet, R.T.; Reis, I.M.A.S.D.; Gouveia, I.C. Plastics and Microplastic in the Cosmetic Industry: Aggregating Sustainable Actions Aimed at Alignment and Interaction with UN Sustainable Development Goals. Polymers 2022, 14, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizet, D.; Aguiar, M.; Campion, J.F.; Pessel, C.; De Lantivy, M.; Godard, C.; Dezeure, J. Water consumption by rinse-off cosmetic products: The case of the shower. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M.; Marto, J.M. A sustainable life cycle for cosmetics: From design and development to post-use phase. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 35, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphasomboon, T.; Vassanadumrongdee, S. Multi-stakeholder perspectives on sustainability transitions in the cosmetic industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Mingione, M.; Ind, N.; Markovic, S. How to build a conscientious corporate brand together with business partners: A case study of Unilever. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 109, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, S.; Martiniello, L.; Morea, D. The strategic role of the corporate social responsibility and circular economy in the cosmetic industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiscini, R.; Martiniello, L.; Lombardi, R. Circular economy and environmental disclosure in sustainability reports: Empirical evidence in cosmetic companies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 892–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakerjlan, L. The aesthetic nature of corporate social responsibility and greenwashing. Oradea J. Bus. Econ. 2022, 7, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STATISTICS. Dominique Petruzzi, Revenue of the Leading 10 Beauty Manufacturers Worldwide. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/243871/revenue-of-the-leading-10-beauty-manufacturers-worldwide/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Global Information, Inc. Global Cosmetics OEM and ODM Market Size: Status and Forecast 2022–2028. 2023. Available online: https://www.giiresearch.com/report/qyr1206251-global-cosmetics-oem-odm-market-size-status.html (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Deloitte. Beauty Retail: A Closer Look at Current Trends Impacting Beauty Specialist Retailers; Deloitte: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 6–7. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/an/en/services/financial-advisory/perspectives/beauty-retail-a-closer-look-at-current-trends-impacting-beauty-specialist-retailers.html (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- GRI. The GRI Standards Enabling Transparency on Organizational Impacts. 2022, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/wmxlklns/about-gri-brochure-2022.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- TCFD. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. 2017. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- SASB Standards. Available online: https://www.sasb.org/licensing-use/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- CDP. About Us: Search and View Company and City Responses. Available online: https://www.cdp.net/en (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- L’Oréal. 2022 Universal Registration Document. pp. 47–49, 51–252. Available online: https://www.loreal-finance.com/system/files/2023-03/LOREAL_2022_Universal_Registration_Document_en.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Unilever. Annual Report and Accounts 2022. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/files/92ui5egz/production/90573b23363da2a620606c0981b0bbd771940a0b.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Unilever. Sustainability Performance Data. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/planet-and-society/sustainability-reporting-centre/sustainability-performance-data/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- The Estée Lauder Companies Inc. Our Fiscal 2022 Social Impact and Sustainability Report. Available online: https://www.elcompanies.com/~/media/files/e/estee-lauder-companies/universal/our-commitments/2022-si-s-report/sis-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- The Procter & Gamble Company. 2022 Citizenship Report. pp. 19–38. Available online: https://us.pg.com/citizenship-report-2022/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Shiseido Company. Sustainability Report 2021. Available online: https://corp.shiseido.com/sustainabilityreport/en/2021/environment (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Beiersdorf. Beiersdorf-NFS-2022. Available online: https://reports.beiersdorf.com/annual-report/2022/services/downloads.html (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton. 2022 Annual Report. Available online: https://r.lvmh-static.com/uploads/2023/03/lvmh_2022_annual-report.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Kao Corp. Kao Sustainability Report 2022. pp. 9–153. Available online: https://www.kao.com/content/dam/sites/kao/www-kao-com/global/en/sustainability/pdf/sustainability2022-e-all.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- COTY. Beauty That Lasts: FY22 Sustainability Report. pp. 4–26, 47–50. Available online: https://assets.contentstack.io/v3/assets/blted39bd312054daca/blt3750dde78a818f79/637374c32f1aba10d25a6552/COTY-SustainabilityReport_FY22-Final.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Johnson & Johnson. Health for Humanity 2025 Goals. Available online: https://www.jnj.com/health-for-humanity-goals-2025 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- kdc/one. Environmental, Social, Governance Report. pp. 9–25, 46–52. Available online: https://www.kdc-one.com/en/articles/environmental-social-governance-report (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Intercos Group. 2022 Consolidated Non-Financial Statement. pp. 8–9, 25–50, 73–115, 124–128. Available online: https://www.intercos-investor.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Intercos-Group-Non-Financial-Statement-2022.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Sephora. Sustainability. Available online: https://www.inside-sephora.com/en/commitments/sustainability (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Ulta Beauty. 2021 Environmental, Social & Governance Report. pp. 5, 22–34, 40–51. Available online: https://d1io3yog0oux5.cloudfront.net/ulta/files/pages/ulta/db/1975/description/ULTA_002_2021_ESG_Report_v23_ADA_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- DOUGLAS. Respecting Beauty Sustainability Report 2021. pp. 5–10, 26–41, 48–49. Available online: https://corporate.douglas.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Douglas_Sustainability_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Consolidated Set of the GRI Standards; GRI Standards: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-90-8866-133-4.

- Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures Guidance on Metrics, Targets, and Transition Plans; TCFD: Basel, Switzerland, 2021.

- SASB Standards Application Guidance; SASB Standards: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018.

- ISAE 3000; Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information. IAASB: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Sephora. What is Clean + Planet Positive at Sephora? Available online: https://www.sephora.com/beauty/eco-friendly-beauty?icid2=homepage_reassurancebanner3_multi-world_program_cleanplanetpositive_us_rwd_banner_060223 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Douglas. Clean Beauty Guide. Available online: https://www.douglas.de/de/c/clean-beauty/11 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- SBTi. What Are ‘Science-Based Targets’? Available online: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/how-it-works (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Batista, L.; Larsen, A.T.; Davis-Peccoud, J.; Häuptli, M. Sustainability in Retail: Practical Ways to Make Progress. Bain & Company. 2022. Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/sustainability-in-retail/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Rahman, S.U.; Nguyen-Viet, B. Towards sustainable development: Coupling green marketing strategies and consumer perceptions in addressing greenwashing. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2420–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, A.; Wilfing, H.; Straus, E. Greenwashing and bluewashing in black Friday-related sustainable fashion marketing on Instagram. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Marcos, A.; Castro, J.; Apaolaza, V. Perspectives: Advertising and climate change–Part of the problem or part of the solution? Int. J. Adverting 2023, 42, 430–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, K.; Tanoue, R.; Kunisue, T.; Tue, N.M.; Fujii, S.; Sudo, N.; Tomohiko, I.; Kei, N.; Agus, S.; Annamalai, S. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in surface water and fish from three Asian countries: Species-specific bio-accumulation and potential ecological risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Oréal. Inside Our Products. Available online: https://inside-our-products.loreal.com/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Zor, S. Conservation or revolution? The sustainable transition of textile and apparel firms under the environmental regulation: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrina, U.; Hidayatno, A.; Zagloel, T.Y.M. A model-based strategy for developing sustainable cosmetics small and medium industries with system dynamics. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephora. Sephora Accelerate. Available online: https://sephoraaccelerate.com/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Amarjit, S. Certifications in Cosmetics; COSSMA: Ettlingen, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://www.cossma.com/marketing/article/certifications-in-cosmetics-36589.html (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Kolling, C.; Ribeiro JL, D.; de Medeiros, J.F. Performance of the cosmetics industry from the perspective of Corporate Social Responsibility and Design for Sustainability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, D.; Gao, Z. Sustainable Design Strategy of Cosmetic Packaging in China Based on Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatt, I.J.; Refalo, P. Life cycle assessment of recyclable, reusable and dematerialised plastic cosmetic packages. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1196, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warn, G. 79% of Consumers have Difficulty Trusting Beauty Brands’, According to new Provenance Report. British Beauty Council. 2022. Available online: https://britishbeautycouncil.com/skin-deep-beauty-report/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Nemes, N.; Scanlan, S.J.; Smith, P.; Smith, T.; Aronczyk, M.; Hill, S.; Lewis, S.L.; Montgomery, A.W.; Tubiello, F.N.; Stabinsky, D. An integrated framework to assess greenwashing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, S.; Jorge, J.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto JO AN, A. A step forward on sustainability in the cosmetics industry: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Eco Beauty Score Consortium. Available online: https://www.ecobeautyscore.com/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Patak, M.; Branska, L.; Pecinova, Z. Consumer intention to purchase green consumer chemicals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, V.; Agrawal, R. Barriers to consumer adoption of sustainable products—An empirical analysis. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 858–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, H.; Sun, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Li, W. Does environmental regulation promote corporate green innovation? Empirical evidence from Chinese carbon capture companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Sources | Targets, Goals, Commitments | Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| L’Oréal, Clichy, France | 2022 Universal, Registration Document [65] | Climate (GHG, Energy), Water (Water, All Aquatic Ecosystems), Biodiversity (Sourcing, Deforestation), Resources (Formula, Package, Store, Waste) | GRI TCFD SASB [81,82,83] |

| Unilever, London, UK | Annual Report and Accounts 2022 [49,66]; Sustainability Performance Data [67] | Climate Action (GHG), Protect and Regenerate nature (Deforest, Sourcing, Water, Formula), Waste-Free World (Plastic Package, Waste) | TCFD |

| Estée Lauder, New York, NY, USA | Fiscal 2022 Social Impact and Sustainability Report [68] | Climate and Energy, Water, Sourcing (Biodiversity), Packaging, Ingredient Transparency | GRI TCFD SASB |

| P&G, Cincinnati, OH, USA | 2022 Citizenship Report [69] | Climate (GHG, Energy), Waste (Package, Waste), Water, Nature (Sourcing, Deforestation) | TCFD |

| Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan | Sustainability Report 2021 [70] | Reducing Our Environmental Footprint (CO2, Water, Waste), Developing Sustainable Products (Packaging, Formula/Ingredients), Promoting Sustainable and Responsible Procurement (Palm Oil, Paper) | TCFD |

| Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany | Sustainability Highlight Report 2022 [26] Beiersdorf-NFS-2022 [71] | For a Climate Care Future (GHG, Energy), For Fully Circular Resources (Formula, Package, Waste), For Sustainable Land Use (Sourcing), For Regenerative Water (Water, Formula) | GRI TCFD |

| LVMH, Paris, France | 2022 Annual Report [72] | Biodiversity (Sourcing, Forest), Circular Design (Package), Traceability/Transparency, Climate (GHG, Energy) | GRI TCFD |

| Kao, Tokyo, Japan | Sustainability Report 2022 [73] | Decarbonization, Zero Waste (Package, Waste), Water Conservation, Air and Water Pollution Prevention, Responsibly Sourced Raw Materials | GRI TCFD |

| Coty, New York, NY, USA | FY22 Sustainability Report [74] | Package, Sourcing, GHG, Energy | ISAE3000 [84] |

| Johnson& Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA | 2021 Health for Humanity Report [75] | GHG, Energy | GRI SASB |

| COSMAX, Seongnam, South Korea | 2022 Sustainability Report [27] | Formula, Packaging, Sourcing | GRI TCFD SASB |

| kdc/one, Quebec, Canada | Environmental, Social, Governance Report 2021 [76] | Energy, GHG, Water, Waste | GRI |

| Intercos, Agrate Brianza, Italy | Consolidated Nonfinancial Statement 2022 [77] | Formula, GHG, Sourcing, Waste | TCFD GRI |

| Sephora, Paris, France | www.inside-sephora.com/en/, accessed on 30 May 2023. [78] | Climate, Sourcing, Eco-Design and Product Transparency, Reduce–Reuse–Recycle | |

| Ulta Beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | 2021 Environmental, Social and Governance Report [79] | Reducing Emissions, Sustainable Packaging | TCFD SASB |

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | Sustainability Report 202 [80] | GHG, Formula, Packaging | GRI SASB |

| Company | Targets, Goals, and Commitments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate/ Energy | Packaging | Sourcing | Water | Waste | Formula | Pollution | |

| L’Oréal, Clichy, France | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Unilever, London, UK | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Estée Lauder, New York, NY, USA | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ||

| P&G, Cincinnati, OH, USA | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| LVMH, Paris, France | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Kao, Tokyo, Japan | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Coty, New York, NY, USA | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA | ● | ||||||

| COSMAX, Seongnam, South Korea | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| kdc/one, Quebec, Canada | ● | ○ | ● | ● | |||

| Intercos, Agrate Brianza, Italy | ● | ● | ● | ○ | |||

| Sephora, Paris, France | ◐ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Ulta Beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | ○ | ● | |||||

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Company | Targets, Goals, Commitments |

|---|---|

| L’Oréal, Clichy, France | 2030: Evaluate all formulas thanks to our environmental test platform |

| Unilever London, UK | 2030: 100% of our ingredients will be biodegradable |

| Estée Lauder, New York, NY, USA | 2025: Develop a glossary and provide information about the uses of ingredients |

| Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan | Reduce our environmental and social impact by using sustainably sourced raw materials |

| Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany | 2023: Eucerin 100% free of microplastics 2021: Nivea 100% free of microplastics 2025: 100% biodegradable polymers in our European product formulations |

| Kao, Tokyo, Japan | 2025: 100% of factories which disclose VOC and COD emissions |

| COSMAX, Seongnam, South Korea | 2030: Microplastic-free suspension of production of existing products; discontinuity of raw materials |

| Intercos, Agrate Brianza, Italy | Creation of products qualified based on the environmental and ethical profile, strengthening the compliance of new formulations with our Clean List. |

| Ulta Beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | Monitor the landscape of trusted ingredients and ingredients |

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | Clean products that are free from certain criticized ingredients |

| Retailer | Environmental Standards | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sephora, Paris, France | Clean + Planet Positive Standards Clean: the avoidance of certain ingredient to be harmful to human health and the environment. Responsible packaging: 100% of products must reduce and eliminate all unnecessary material. Design for recyclability (2021: 50%~, 2023: ~75%, 2025: 90%) Reimagine of core brands assortment (2021: 50%, 2023: 75%, 2025: 100%) −30% PCR, biomaterials, 75% recycled, refillable, FSC-certified, etc.) Climate commitments must (meet at least one) 100% renewable energy, GHG reduction targets and action plan, carbon-neutral operations Sustainable sourcing (must meet all) 100% of palm oil and palm kernel oil, MICA; by 2022, zero microplastics and 100% cruelty free Environmental giving: committed to giving AT LEAST 1% OF PROFIT | [85] |

| Ulta Beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | Conscious Beauty at Ulta BeautyTM Clean ingredients, cruelty free, vegan, sustainable packaging (50% recycled packing, 30% PCR for cosmetic compact lids), positive impact (highlight brands with philanthropic efforts) | [79] |

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | Clean Beauty Guide Free from cyclic silicones, parabens, harsh sulfates, mineral oils, ethanolamine, synthetic fragrances (<1%), phthalates, formaldehydes and formaldehyde releaser, PEGs, chemical SPF cruelty-free | [80,86] |

| Company | Targets, Goals, Commitments | Basis | Progress | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L’Oréal, Clichy, France | 2025: Scopes 1, 2—carbon neutrality (vs. 2016) 2030: 25% reduction per finished product (tCO2 eq/kg of formulas sold) (vs. 2016) | SBTi | 2022: 65% 2022: −24% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Unilever, London, UK | 2030: Scopes 1, 2—zero (vs. 2015) 2039: Scopes 1, 2, 3—net zero (vs. 2015) | SBTi | 2022: 34.31 2022: −68% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Estée Lauder, New York, NY, USA | 2030: Scopes 1, 2—50% reduction (vs. 2018) Scope 3—60% reduction (vs. 2018) | SBTi | FY2022: 54% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| P&G, Cincinnati, OH, USA | 2030: Scopes 1, 2—50% reduction (vs. 2010) 2039: Scope 3—net zero | SBTi | FY 2022: 57% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan | 2026: Carbon neutral 2030: Scopes 1, 2—46.2% reduction (vs. 2019) 2030: Scope 3—55% reduction (vs.2019) | SBTi | Plan to disclose in 2023 | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany | 2025: Scopes 1, 2, 3—30% reduction (vs. 2018) 2030: 100% climate-neutral production sites | SBTi | 2022: 17% 2022: 7% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| LVMH, Paris, France | 2026: Scopes 1, 2—50% reduction (vs. 2019) 2030: Scope 3—55% reduction/protection | SBTi | 2022: 11% 2022: 77% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Kao, Tokyo, Japan | 2030: Scopes 1, 2—55% reduce (vs. 2017) 2030: 22% reduction in absolute full lifecycle (vs. 2017) | SBTi | 2022: 20% 2022: 4% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Coty, New York, NY, USA | 2030: Scopes 1, 2—50% reduction (vs. 2019) 2030: Scope 3—28% reduction (vs. 2019) | SBTi | FY2022: 70.6% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA | 2030: Carbon neutrality Scopes 1, 2—60% reduction (vs. 2016) 2030: Scope 3—20% reduction (vs. 2016) | SBTi | 2021: 50% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| COSMAX, Seongnam, South Korea | 2025: Scopes 1, 2—25% reduction (vs. 2017) 2030: Scopes 1, 2—30% reduction (vs. 2017) | DNV Business Assurance Korea | 2021: 27% 2021: 23% | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| kdc/one, Quebec, Canada | 2025: Trace 100% of Scope 1 and Scope 2 to renewable energy | SBTi | FY 2022: 100% of Scopes 1, 2’s emissions from manufacturing sites offset with renewable energy | Scopes 1, 2 |

| Intercos, Agrate Brianza, Italy | 2025: Scopes 1, 2—20% reduction | SBTi | 2022–2022: −32% | Scopes 1, 2 |

| Sephora, Paris, France | 2026: 50% reduction (stores, headquarters, distribution center) | |||

| Ulta Beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | 2× renewable energy credits commitment in 2022 | SBTi | 2021: SBT setting | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | 2025: Scopes 1, 2—carbon neutral FY2022/23: Roadmap for Scope 3 | SBTi | Scopes 1, 2, 3 |

| Company | Targets, Goals, Commitments | Progress | Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| L’Oréal, Clichy, France | 2030: 100% of the plastic package from recycled or biobased sources (50% by 2025) | 2022: 26% | Recycled material |

| 2030: 20% reduction in intensity the quantity of packaging used for our products (vs. 2019) | 2022: −3% | ||

| 2025: 100% refillable, reusable, recyclable, or compostable plastic packaging | 2022: 30% | ||

| Unilever, London, UK | 2025: 25% recycled plastic | 2022: 21% | Recycled plastic |

| 2025: 50% virgin plastic reduction by 2025 | 2022: −13% | ||

| 2025: 100% reusable, recyclable, or compostable plastic packaging | 2022: 55% | ||

| 2025: Collect and process more plastic than we sell | 2022: 58% | ||

| Estée Lauder, New York, NY, USA | 2025: recyclable, refillable, reusable, recycled, or recoverable packaging (75–100%) | FY2022: 63% | Total weight of product package |

| 2025: increase PCR material to 25% or more. | FY2022: 17% | ||

| 2030: reduce 50% virgin petroleum content | FY2022: 87% | ||

| 2025:100% of our forest-based fiber cartons FSC-certified | FY2022: 95% | ||

| P&G, Cincinnati, OH, USA | 2030: 100% recyclable or reusable consumer packaging | FY2022: 79% | Plastic packaging Recycled plastic resin |

| 2030: 50% reduction in virgin petroleum plastic (vs.2017) | FY2022: 8% | ||

| 100% of our paper packaging to be either recycled or third-party-certified virgin content | FY2022: 99% | ||

| 2025: 50% of our virgin paper packaging is FSC™-certified | FY2022: 68% | ||

| Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan | 2025: 100% sustainable packaging for sale of product with plastic packaging. | 2022: 64% | |

| Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany | 2025: 100% of refillable, reusable, recyclable | 2022: 67% | Fossil-based virgin plastic |

| 2025: 30% recycled material (vs. 2019): | 2022: 10% | ||

| 2025: 50% reduction in fossil-based virgin plastic (vs. 2019) | 2022: 15% | ||

| LVMH, Paris, France | 2026: Zero fossil-based virgin plastic (vs. 2019) 2030: 100 % of new products covered by a sustainable design | 2022: 8% reduction | Weight of packaging |

| Kao Tokyo, Japan | 2030: to begin decline Quantity of fossil-based plastics | 2021:104 thousand | Plastic package Plastic in refill replacement |

| 2030: 300-million quantity of innovative film-based packaging penetration for Kao and others per annum | 2021: 11 million | ||

| 2030: % of recycled plastic (to disclose in 2023) | 2021: 1% | ||

| 2025: Product-launch practical use of innovative film-based packaging made from collected pouches | 2021: product launch | ||

| 2025: 100% of recycled plastic in PET containers (Japan) | 2021: 19% | ||

| Coty, New York, NY, USA | 2025: 100% folding box boards made with FFSC- or PEFC-certified material 2030: 20% reduction in packaging (vs. 2019) 2030: 30% usage of PCR materials | New target set in FY22. | |

| COSMAX, Seongnam, South Korea | 2025: 100% of recycled plastic | ||

| kdc/one, Quebec, Canada | 2025: 100% reusable or recyclable packaging | Rollout started | Type of package |

| Ulta, Ulta Beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | 2025: 50% of packaging will be recyclable, refillable, or made from recycled or bio-sourced materials | ||

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | 2030: 50% of all new Douglas brands products will be using recycled material |

| Company | Climate Change | Forests | Water Security | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| L’Oréal, Clichy, France | A | A | A | AAA | AAA | AAA- | A | A | A |

| Unilever, London, UK | A | A | A | A-A-A- | AAA- | AAA- | A | A | A- |

| Estée Lauder, New York, NY, USA | A | A | A- | A-B | A-B | A-B | A- | A- | A |

| P&G, Cincinnati, OH, USA | B | A- | A- | No response | BA- | BA- | B | B | B |

| Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan | B | A- | A- | No response | BA- | BA- | B | B | B |

| LVMH, Paris, France | B | A- | A | BBBB | A-A-A- | AAA | B | A- | A |

| Beiersdorf, Hamburg, Germany | A | A- | A | A- | AB | AA | B | B | A |

| Kao, Tokyo, Japan | A | A | A | AA- | AA | AA | A | A | A |

| Coty, New York, NY, USA | A- | B | B | No response | No response | No response | No response | No response | No response |

| Johnson &Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA | A | A | A | A-B | A-B | BB | A | A- | A- |

| Sephora, Paris, France | |||||||||

| Ulta beauty, Bolingbrook, IL, USA | No response | No response | C | No response | No response | No response | |||

| Douglas, Düsseldorf, Germany | No response | No response | No response | ||||||

| COSMAX, Seongnam, South Korea | Submitted Unavailable | B | B | No response | No response | No response | No response | No response | B- |

| kdc/one, Quebec, Canada | Submitted Unavailable | Submitted Unavailable | Submitted Unavailable | Submitted Unavailable | |||||

| Intercos, Agrate Brianza, Italy | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, H.Y.; Kwon, K.H. Sustainable Assessment of the Environmental Activities of Major Cosmetics and Personal Care Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813286

Lim HY, Kwon KH. Sustainable Assessment of the Environmental Activities of Major Cosmetics and Personal Care Companies. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813286

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Hea Young, and Ki Han Kwon. 2023. "Sustainable Assessment of the Environmental Activities of Major Cosmetics and Personal Care Companies" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813286