ESG Strategy and Financial Aspects Using the Example of an Oil and Gas Midstream Company: The UNIMOT Group

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG: Basic Assumptions

- Raising ESG issues at the investment analysis stage and during the decision-making process;

- Implementing ESG rules in company policies and promoting the engagement and active participation in the functioning of the company;

- Open presentation of ESG aspects by entities cooperating with the enterprise;

- Promoting the implementation of ESG factors as part of investment activities;

- Engaging in cooperation in order to increase the effectiveness of SRI implementations;

- Preparing reports covering the activities and the degree of implementation of SRI principles.

- Sustainability-themed investment—this strategy focuses on investing in the area of sustainable development; therefore, it is also referred to as thematic. Investors’ decisions regarding investment choices in this case are in line with broad social and environmental objectives, for example, increasing eco-innovation, moving towards a circular economy, etc.

- Best-in-class investment selection—expansion of the investment portfolio takes place by including companies that have achieved the best results in terms of ESG factors in a specific sector of the economy.

- Exclusion of holdings of investment universe companies—assumes reducing the investment portfolio by companies that participate in promoting issues considered controversial in ethical and social terms, including those related to alcohol, gambling, pornography, etc.

- Norm-based screening—the selection of companies for the investment portfolio is based on the exclusion of those entities whose activities differ from the standards in the area of environmental protection, social responsibility, and corporate governance.

- ESG integration factors in financial analysis—consists of taking into account the ESG criteria in the financial analysis and assessing their impact on the financial result.

- Engagement and voting on sustainability matters—emphasizes an active participation in the implementation of the principles of social responsibility in the enterprise, and is therefore of a long-term nature. Shareholders use their voting rights to contribute to sustainability-related initiatives.

- Impact investing—considered as social investment, the purpose of which is to invest capital in various types of entities in such a way that it ultimately has a positive impact on society and the environment.

- Environmental—for example: it assumes investing in companies whose activities are aimed at protecting biodiversity;

- Social—for example: investments are made in companies that respect human rights;

- Corporate governance—for example: companies that have a transparent and open information policy play a key role in this respect.

- Selecting areas of industry where the assumption of risks and the use of opportunities in the area of ESG are particularly emphasized;

- Choosing the most effective way to implement the ESG strategy;

- Identification of material indicators impacting the company’s financial performance.

- Environmental (E), where they include climate change, including any anomalies and the effects of global warming; the increased incidence of more noticeable natural disasters; issues related to the depletion of natural resources; and environmental pollution;

- Social (S), where the following aspects are taken into account: the occurrence of financial exclusion and, thus, among other things, the risk of poverty and growing inequalities in society; the development of social illnesses, especially obesity, diabetes, etc.; disrespect for human and workers’ rights as manifested by excessive work assignments, mobbing, and discrimination; and the demographic decline in and aging of the population;

- Corporate governance (G), with risks relating to ignoring applicable regulations, leading to fraudulent financial transactions, counterfeiting, collusive pricing, and non-statutory complaint procedures; breaches of professional ethics standards, including through dishonest contracts, controversial marketing strategies, and misleading advertising to the public; standards of equal treatment of stakeholders; conflict of interest issues and organizational structure; and transparency of information policy.

2.2. UNIMOT Group: Specifics of Functioning

- Diesel fuel—the Group’s activities relate to the wholesale of petrol and diesel fuels. Sales of liquid fuels in Poland are conducted according to two systems, i.e., franco, where the sale of fuel also includes its delivery, and loco, where the customer is responsible for the transport of the sold fuel. The Group’s business customers include construction and transport companies, wholesalers and petrol stations, and agriculture;

- Liquefied petroleum gas—the sale of LPG is conducted on wholesale and retail markets. Gas is supplied to filling stations and heating tanks, including our own (leased out) and those belonging to individual customers and other companies. The specific nature of the industry significantly affects the diversity of customers;

- Natural gas—the Group’s activities in this area include trading in natural gas on the TGE (Towarowa Giełda Energii—Energy Stock Exchange) and the over-the-counter market, as well as the sale and distribution of gas to the final recipient;

- Biofuels—products sold as independent fuel that is dedicated to diesel-powered vehicles. It should be noted that, unlike traditional diesel, biofuels emit significantly less harmful substances into the environment and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this respect, the Group offers diesel B100 and methyl esters;

- Electricity—in this area, the Group conducts wholesale energy trading using exchange and brokerage platforms (Tradea) and the sale of energy to the final customer using a foreign infrastructure;

- Asphalt products—from 2019. The Group imports and sells asphalt products in Poland (AVIA Bitumen);

- Engine oils and lubricants—the sale and distribution of these products was initiated in 2019 on the Chinese market. Hence, the actions taken in 2018 involved the creation of an additional company and the launch of an office in Shanghai. In 2019, using UNIMOT’s distribution network, oil sales in Ukraine also started. In addition, from 2020, the Group pursued sales of AVIA oils on the domestic market;

- Photovoltaics—the Group has sold photovoltaic systems under the AVIA Solar brand since 2020. Customers serviced in this area belong to the business sector, and the offer addressed to them includes the production of photovoltaic panels (from 2021), installation of equipment, the possibility of buying back the generated energy, energy storage, and supplying it with power from the grid. In 2021, the sector was expanded to include photovoltaic farms. The Group is assuming the dynamic development of this area of business and thus creating added value from it in the future.

3. Materials and Methods

- Allowed us to build a correlation matrix between the selected variables;

- Based on the method of ordinary least squares (OLS), it enabled the development of a sample logit model between the dependent and independent variables.

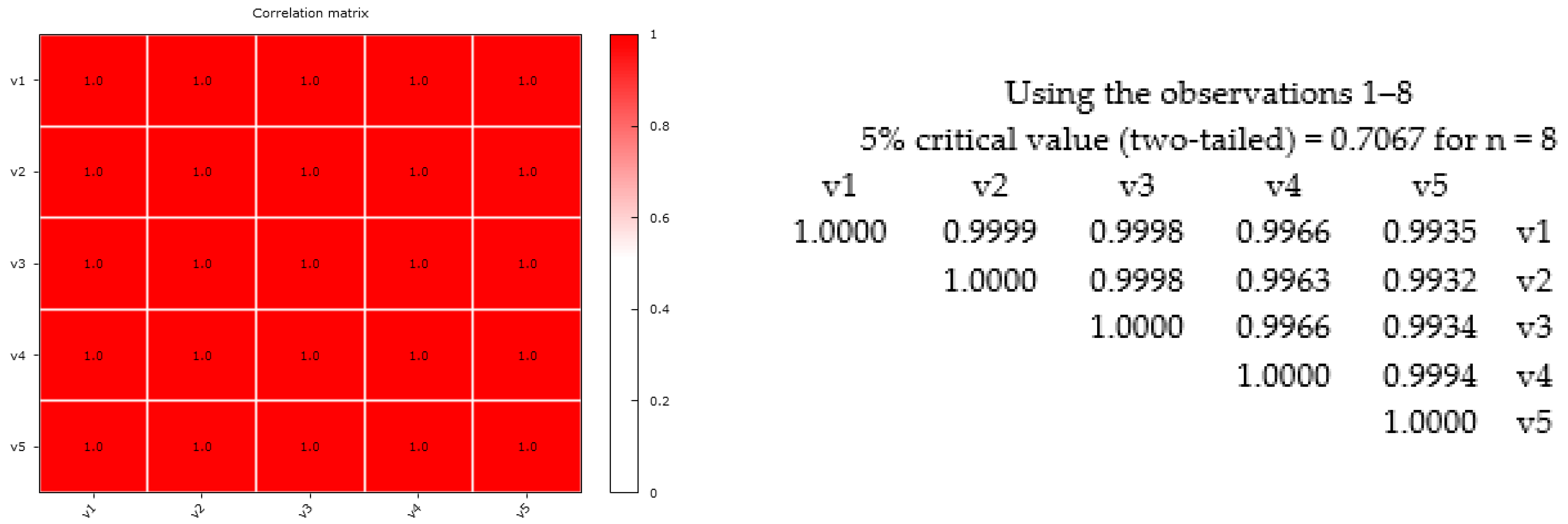

- Years (variables: v1–v5) in the area of selected data and financial indicators (variables: x1–x3)—Figure 2a;

- Years (variables: v1–v5) in the area of sales revenue in specific segments (variables: x11–x17)—Figure 2b;

- Years (variables v1–v5) in the area of sales volume by segment (variables: x4–x10)—Figure 3.

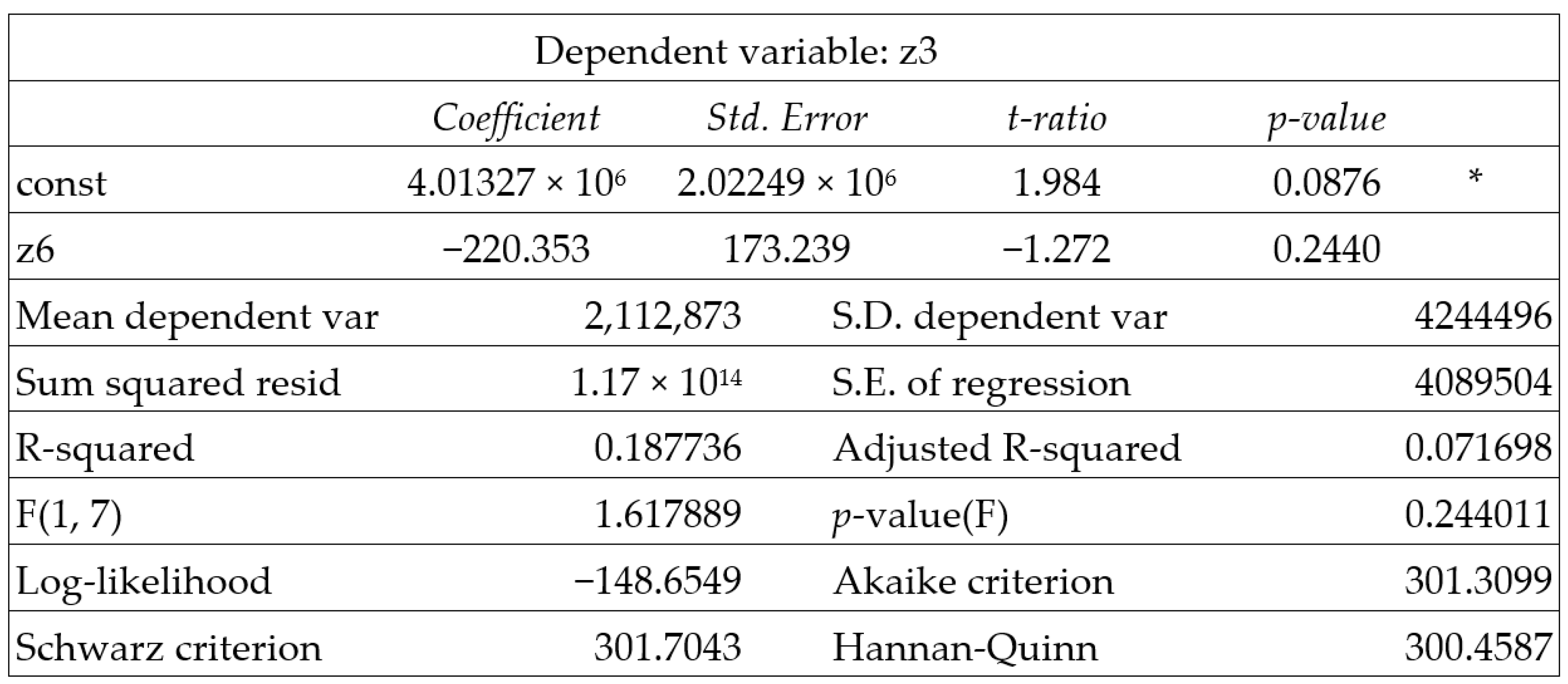

- Financial (dependent variables: z1–z3) and non-financial (independent variables: z4–z6) data in a particular year;

- Non-financial data in a particular year (dependent and independent variables: z4–z6).

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mirza, N.; Naeem, M.A.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Arfaoui, N.; Oliyide, J.A. Are sustainable investments interdependent? The international evidence. Econ. Model 2023, 119, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szadziewska, A.; Majchrzak, I.; Remlein, M.; Szychta, A. Rachunkowość Zarządcza a Zrównoważony Rozwój Przedsiębiorstwa; IUS Publicum: Katowice, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzitheodorou, K.; Skouloudis, A.; Evangelinos, K.; Nikolaou, I. Exploring socially responsible investment perspectives: A literature mapping and an investor classification. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European SRI Study 2016. Available online: https://www.mites.gob.es/ficheros/rse/documentos/spainsif/SRI-study-2016-LR.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Czerwonka, M. Inwestycje odpowiedzialne społecznie (SRI)-inwestowanie alternatywne. Finanse 2011, 1, 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- European SRI Study 2018 Created with the Support of. Available online: www.candriam.com (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Lulewicz-Sas, A.; Kilon, J. The Effectiveness of SRI Funds in Poland. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Y.; Li, X.; Càmara-Turull, X. Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5052–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korombel, A.; Ławińska, O. Social Media in Building Relationships between Companies and Representatives of Generation Z in the Customer Relationship Management Concept. 2021. Available online: http://excelingtech.co.uk/ (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Wang, D.; Peng, K.; Tang, K.; Wu, Y. Does Fintech Development Enhance Corporate ESG Performance? Evidence from an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Qu, T. An ESG Assessment Approach with Multi-Agent Preference Differences: Based on Fuzzy Reasoning and Group Decision-Making. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yu, G. The Impact of General Manager’s Responsible Leadership and Executive Compensation Incentive on Enterprise ESG Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. Sustainability Matters: Unravelling the Power of ESG in Fostering Brand Love and Loyalty across Generations and Product Involvements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Kiseleva, E.; Terzani, S. Evaluating the Intra-Industry Comparabilityof Sustainability Reports: The Case of the Oil and Gas Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, D.G.; Todorova, N. Big oil in the transition or Green Paradox? A capital market approach. Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M.; Gülay, G.; Ergun, K. Impact of ESG performance on firm value and profitability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Sharma, D. Do Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Performance Scores Reduce the Cost of Debt? Evidence from Indian firms. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2022, 16, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, K.; Kiosses, N.; Tampakoudis, I.; Abdelaziz, F.B. Measuring the efficiency of mutual funds: Does ESG controversies score affect the mutual fund performance during the COVID-19 pandemic? Oper. Res. 2023, 23, 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Elahi, E.; Khalid, Z. Do Green Finance Policies Foster Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance of Corporate? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahnen, J.; Rocholl, J.; Thum, M. A Primer on Green Finance: From Wishful Thinking to Marginal Impact. Rev. Econ. 2023, 74, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhu, Z. The effect of ESG rating events on corporate green innovation in China: The mediating role of financial constraints and managers’ environmental awareness. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.; Kumari, D.; Johann, M.; Mladenović, D. The impact of environmental, social and governance score on shareholder wealth: A new dimension in investment philosophy. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 8, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellili, N.O.D. Bibliometric analysis and systematic review of environmental, social, and governance disclosure papers: Current topics and recommendations for future research. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 092001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivascu, L.; Domil, A.; Sarfraz, M.; Bogdan, O.; Burca, V.; Pavel, C. New insights into corporate sustainability, environmental management and corporate financial performance in European Union: An application of VAR and Granger causality approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 82827–82843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, Ö.; Bax, K.; Czado, C.; Paterlini, S. Environmental, Social, Governance scores and the Missing pillar—Why does missing information matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Env. Manag. 2022, 29, 1782–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCahery, J.A.; Pudschedl, P.C.; Steindl, M. Institutional Investors, Alternative Asset Managers, and ESG Preferences. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2022, 23, 821–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.B.; Park, H.C. Sustainability Management through Corporate Social Responsibility Activities in the Life Insurance Industry: Lessons from the Success Story of Kyobo Life Insurance in Korea. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Tuo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hou, X. Green Fiscal Policy and ESG Performance: Evidence from the Energy-Saving and Emission-Reduction Policy in China. Energies 2023, 16, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, T.C.; Junkus, J.C. Socially Responsible Investing: An Investor Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarone, F.; Lampariello, L.; Merolla, D.; Ricci, J.M.; Sagratella, S.; Sasso, V.G. A bilevel approach to ESG multi-portfolio selection. Comput. Manag. Sci. 2023, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matczak, K.; Wojciechowski, J.; Martysz, C. Inwestowanie zrównoważone w zarządzaniu portfelem inwestycyjnym. Kol. Zarządzania I Finans. 2019, 176, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja-Cieszyńska, H.E.; Kordela, D. Sustainability Reporting in Energy Companies—Is There a Link between Social Disclosures, the Experience and Market Value? Energies 2023, 16, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. The market for socially responsible investments: A review and evaluation. In CSR and Socially Responsible Investing Strategies in Transitioning and Emerging Economies; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Goel, P.; Sharma, A.; Rana, N.P. As you sow, so shall you reap: Assessing drivers of socially responsible investment attitude and intention. Technol. Forecast Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Investing: A Balanced Analysis of the Theory and Practice of a Sustainable Portfolio; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lulewicz-Sas, A. Społecznie odpowiedzialne inwestowanie narzędziem koncepcji społecznie odpowiedzialnego biznesu. Ekon. I Zarządzanie 2014, 6, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikacz, H. Działalność Przedsiębiorstwa w Obszarach Środowiskowym, Społecznym i Ładu Korporacyjnego: Teoria i Praktyka; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jamróz, P. Structure of Socially Responsible Investment Funds in Selected European Countries. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego Finans. Rynk. Finans. Ubezpieczenia 2017, 89, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, L.; Ortiz, N.; Moreno, G.; Páez-Gabriunas, I. The Effect of Company Ownership on the Environmental Practices in the Supply Chain: An Empirical Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I. Environmental, social, and governance (esg) practice and firm performance: An international evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 23, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Global Compact Office. The Global Compact Leaders Summit, United Nations Headquarters; Final Report; UN Global Compact Office: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, Z. Social responsibility portfolio optimization incorporating ESG criteria. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, P. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Laws, Regulations and Practices in the Digital Era; Kluwer Law International: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cicirko, M. Znaczenie czynników środowiskowego, społecznego i ładu korporacyjnego (ESG) we współczesnej gospodarce. Percepcja inwestycji ESG wśród studentów uczelni ekonomicznej. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne. Teor. I Prakt. 2022, 151, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimova, O.V.; Volkov, M.; Koroleva, D. The impact of ESG factors on asset returns: Empirical research. Financ. Theory Pract. 2021, 25, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, L.; Dreassi, A.; Girardone, C.; Piserà, S. Do ESG strategies enhance bank stability during financial turmoil? Evidence from Europe. Eur. J. Financ. 2022, 28, 1173–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, G.; Fagernes, R.V.K.; Elmarzouky, M.; Hossain, K.A.B.M.A. The ESG Disclosure and the Financial Performance of Norwegian Listed Firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, J.; McKinnon, M.; Van der Byl, C. Green Gaps: Firm ESG Disclosure and Financial Institutions’ Reporting Requirements. J. Sustain. Res. 2021, 3, e210006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus Strategy Env. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Arslan, S.; Birkan, A.O. ESG practices and corporate financial performance: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarmuji, I.; Maelah, R.; Tarmuji, N.H. The Impact of Environmental, Social and Governance Practices (ESG) on Economic Performance: Evidence from ESG Score. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2016, 7, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Singhania, M.; Hasan, M.; Yadav, M.P.; Abedin, M.Z. Non-financial disclosures and sustainable development: A scientometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almubarak, W.I.; Chebbi, K.; Ammer, M.A. Unveiling the Connection among ESG, Earnings Management, and Financial Distress: Insights from an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.; Habib, A. How impact investing firms are responding to sustain and grow social economy enterprises in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 18, e00347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojoianu, T.F.; Hoepner, A.G.F.; Lin, Y. Private market impact investing firms: Ownership structure and investment style. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 84, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B. ESG Investing for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mandas, M.; Lahmar, O.; Piras, L.; De Lisa, R. ESG in the financial industry: What matters for rating analysts? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 66, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluchna, M.; Roszkowska-Menkes, M.; Kamiński, B. From talk to action: The effects of the non-financial reporting directive on ESG performance. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materiality Map Screenshot. Available online: https://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MMap-2021.png (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Tyson, E. Investing All-in-One for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Isaksson, R.; Ramanathan, S.; Rosvall, M. The sustainability opportunity study (SOS)—Diagnosing by operationalising and sensemaking of sustainability using Total Quality Management. TQM J. 2023, 35, 1329–1347. Available online: https://www.sasb.org/standards/download/ (accessed on 13 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, J. An empirical analysis of the impact of ESG on financial performance: The moderating role of digital transformation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1256052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronalter, L.M.; Bernardo, M.; Romaní, J.M. Quality and environmental management systems as business tools to enhance ESG performance: A cross-regional empirical study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 9067–9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumente, I.; Bistrova, J. Esg importance for long-term shareholder value creation: Literature vs. practice. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundouri, P.; Pittis, N.; Plataniotis, A. The Impact of ESG Performance on the Financial Performance of European Area Companies: An Empirical Examination. EWaS5 2022, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finance, S.S. Handbook on Sustainable Investments: Background Information and Practical Examples for Institutional Asset Owners; CFA Institute Research Foundation: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNIMOT. Raport ESG. 2021. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/raport-esg-2021.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Informacje o Grupie UNIMOT. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/o-grupie/unimot/informacje-o-unimot/ (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Wanday, J.; El Zein, S.A. Higher expected returns for investors in the energy sector in Europe using an ESG strategy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1031827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SICS Industry: Oil & Gas—Midstream. Disclosure Topics. Available online: https://sasb.org/standards/materiality-finder/find/?company%5B%5D=PLUNMOT00013&lang=en-us (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Otola, I.; Grabowska, M. Business Models. Digital Transformation and Analytics; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otola, I.; Grabowska, M.; Kozak, M. What constitutes the value in business model for social enterprises? Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 24, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufel, T. Ekonometria. Rozwiązywanie Problemów z Wykorzystaniem Programu GRETL; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mixon, J.W., Jr.; Smith, R.J. Teaching undergraduate econometrics with GRETL. J. Appl. Econom. 2006, 21, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, L.C. Using Gretl for Principles of Econometrics, 5th ed.; Free Software Foundation: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.learneconometrics.com/gretl/index.html (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Cotrell, A. Gretl User’s Guide, Gnu Regression, Econometrics and Time-Series Library; Free Software Foundation: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: http://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl.html (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- UNIMOT. Sprawozdanie Zarządu za 2018 r. 2019. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/unimot-sprawozdanie-zarzadu-2018.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- UNIMOT. Sprawozdanie Zarządu za 2019 r. 2020. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/5-unimot-sprawozdanie-zarzadu-2019.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- UNIMOT. Sprawozdanie Zarządu za 2021 r. 2022. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/sprawozdanie-zarzadu-unimot-za-2022-1.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- UNIMOT. ESG Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/uncategorized/unimot-group-publishes-its-esg-report-for-2022/?lang=en (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- UNIMOT. Dane Finansowe. 2023. Available online: https://www.unimot.pl/relacje-inwestorskie/dane-finansowe/ (accessed on 26 August 2023).

| Industry Sectors |

|---|

| Consumer goods, extractives and minerals processing, financials, food and beverage, healthcare, infrastructure, renewable resources and alternative energy, resource transformation, services, technology and communications, transportation. |

| Material indicators |

| Environment: GHG emissions, air quality, energy management, water and wastewater management, waste and hazardous materials management, ecological impact. Social impact: human rights and community relations, customer privacy, data security, access and affordability, product quality and safety, customer welfare, selling practices and product labeling, data security and privacy. Human capital: labour practices, employee health and safety, employee engagement, diversity and inclusion. Business model and innovation: product design and lifecycle management, business model resilience, supply chain management, materials sourcing and efficiency, physical impacts of climate change. Leadership and governance: business ethics, competitive behaviour, management of the legal and regulatory environment, critical incident risk management, systemic risk management. |

| Popular ESG strategies |

| Screening—consists of accepting or excluding resources within the investment portfolio, in accordance with previously determined criteria. Best-in-class—takes into account the high ESG results in the resource selection process. Stock rating—based on the results of the ESG rating. Value integration—assumes referring to ESG criteria when valuing shares. Thematic—refers to building an investment portfolio in a specific thematic area. Engagement—advocates for the continuation of the postulated position on ESG. Alignment—draws attention to integration with social and environmental goals. Activism—emphasizes the essence of the right to vote, including its impact on the involvement of the enterprise. Systematic—indicates the use of empirical factors. |

| ESG Area | Strategic Objective | Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | I. Systematic reduction in the Group’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions | Development of business based on renewable energy sources |

| Continuous delivery of NCW and NCR responsibilities to the highest standards | ||

| Striving for greenhouse gas neutrality in scopes 1 and 2 | ||

| II. Effective management of UNIMOT Group’s environmental impact | Improving environmental management processes | |

| In-depth analysis of climate risks and opportunities | ||

| Social | III. Increasing the safety, commitment, and skills of employees, and promoting a healthy and active lifestyle among them | Improving safety at work |

| Continuous improvement of staff competence and commitment | ||

| Providing access to private health insurance and sports cards | ||

| IV. Support for social development and young talent | Support for local communities | |

| Supporting young talent and creating opportunities for their development | ||

| Governance | V. UNIMOT Group management for sustainable development | Building a culture of sustainability in the organization |

| Introduction of the Business Partner Code |

| Oil and Gas Midstream | |

|---|---|

| General Issue Category (Dimension) | Disclosure Topics |

| GHG Emissions (Environment) | Greenhouse gas emissions—the activity of enterprises classified in this sector is identified with the generation of significant levels of greenhouse gases and other harmful substances. Undoubtedly, these emissions have a negative impact on the climate, at the same time generating costs for entrepreneurs related to the need to adapt activities to legal regulations. There is also an emerging risk that relates to climate change mitigation. In practice, striving to reduce methane emissions and minimize thier negative impact on the climate is part of the risk of enterprises in the sector, including operational, reputational, and regulatory. |

| Air Quality (Environment) | Air quality—companies from oil and gas midstream release harmful substances into the air, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are dangerous for both the environment and people. In addition to VOCs, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide are also considered to be extremely toxic. |

| Ecological Impacts (Environment) | Ecological mpacts—in this area, the degradation of the natural environment and the risk of a threat to society from the storage and distribution of crude oil, petroleum products, and natural gas are particularly emphasized. The direct impact is associated with the extensive infrastructure of the sea, land (freight and trains), and pipelines, which results in accidental leaks, prohibited discharges, the occupation of areas with an extensive network of pipelines, or established easements in sensitive areas. As a result, there is human interference in ecosystems, which causes the destruction of natural habitats or the migration of species. |

| Competitive Behaviour (Leadership and Governance) | Competitive Bbehaviour—the functioning of enterprises that have pipelines and natural gas storage facilities depends on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and specifying the standards introduced by this institution. These regulations apply to all areas of activity, i.e., from issues related to the calculation of fees to accessibility options for pipelines, as well as decisions related to the location and construction of subsequent facilities. |

| Critical Incident Risk Management (Leadership and Governance) | Operational safety, emergency preparedness, and response—the specificity of the functioning of enterprises belonging to the discussed sector is associated with the handling of a specific type of asset, characterized by a high risk of accidents or leaks. For example, the unexpected release of hydrocarbons into the environment has long-term effects that are unfavourable to the environment, employees, and residents. Therefore, the development of new safety regulations for the operation of pipelines and railways is considered crucial in this respect. |

| Variable | 2017 (v1) | 2018 (v2) | 2019 (v3) | 2020 (v4) | 2021 (v5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected financial data and indicators | ||||||

| Revenue from sales (kPLN) | x1 | 3,009,249 | 3,367,462 | 4,450,180 | 4,769,994 | 8,207,216 |

| Gross profit (kPLN) | x2 | 145,404 | 121,899 | 221,605 | 249,521 | 366,239 |

| EBIT (kPLN) | x3 | 29,896 | 727 | 68,744 | 49,255 | 103,734 |

| Sales volume by segment | ||||||

| Diesel, petrol, biofuels (m3) | x4 | 826,755.4 | 840,366 | 1,121,601 | 1,347,350 | 1,583,850 |

| LPG (T) | x5 | 113,666 | 126,632 | 167,860 | 185,271 | 221,445 |

| Natural gas (GWh) | x6 | 349.9 | 405 | 504.8 | 774.4 | 2507 |

| Electricity (GWh) | x7 | 588.7 | 1529 | 2078.5 | 2573.2 | 3145 |

| Fuels at stations (thousand liters) | x8 | 0 | 47.5 | 75.5 | 107,387 | 179,834 |

| Petroleum products (T) | x9 | 0 | 0 | 21,409 | 48,824 | 56,672 |

| Photovoltaics (KWp) | x10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1391 | 4249 |

| Sales revenue by segment (in kPLN) | ||||||

| Diesel, petrol, biofuels | x11 | 2,610,100 | 2,932,880 | 3,898,509 | 3,845,935 | 6,436,642 |

| LPG | x12 | 251,727 | 301,709 | 343,476 | 342,960 | 645,338 |

| Natural gas | x13 | 32,186 | 44,750 | 47,868 | 71,777 | 552,622 |

| Electricity | x14 | 97,678 | 73,398 | 87,306 | 120,127 | 222,971 |

| Fuel at the stations | x15 | 16,600 | 17,972 | 35,204 | 69,855 | 214,235 |

| Petroleum products | x16 | 0 | 165 | 30,943 | 309,641 | 105,153 |

| Photovoltaics | x17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5018 | 14,756 |

| Selected Financial Data (kPLN) | Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 (z1) | 2021 (z2) | 2022 (z3) | |

| Revenues from sales | 4,819,488 | 8,193,018 | 13,369,364 |

| Gross profit | 249,521 | 366,239 | 954,205 |

| EBIT | 49,255 | 104,410 | 485,374 |

| EBITDA | 58,293 | 116,418 | 502,463 |

| Net profit | 75,961 | 75,961 | 373,897 |

| Equity capital | 265,881 | 325,875 | 703,794 |

| Long-term liabilities | 52,690 | 92,297 | 96,614 |

| Short-term liabilities | 471,764 | 813,116 | 864,869 |

| Total assets | 790,335 | 1,231,288 | 1,665,277 |

| Selected Non-Financial Data | 2020 (z4) | 2021 (z5) | 2022 (z6) |

| Total number of accidents | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total fuels consumed in transport (MWh) | 4270.50 | 5429.50 | 6691.00 |

| Total fuels consumed by buildings and installations (MWh) | 550.6 | 16,563.90 | 10,408.30 |

| Total energy consumption from all sources (MWh) | 5347.40 | 22,960.10 | 19,136.40 |

| Energy from all renewable sources (MWh) | 285.7 | 540.3 | 948.3 |

| Energy from all non-renewable sources (MWh) | 5069.60 | 22,419.70 | 18,188.10 |

| Total energy from all sources (MWh) | 5355.40 | 22,960.10 | 19,136.40 |

| Electricity generated from RESs (MWh) | 0.50 | 4.20 | 36.30 |

| Total GHG scope-1 emissions (Mg CO2e) | 1257.30 | 3478.00 | 3074.10 |

| Scope 2 location-based (Mg CO2e) | 326.7 | 750.2 | 1318.7 |

| Scope 2 market-based (Mg CO2e) | 173.4 | 445,7 | 797.20 |

| Scopes 1 + 2 location-based + scope 3 (Mg CO2e) | 1628.6 | 4300.90 | 4517.10 |

| Scopes 1 +2 market-based (Mg CO2e) | 1475.3 | 3956.40 | 3995.70 |

| GHG scope-3 emissions (Mg CO2e) | 44.6 | 76.90 | 124.40 |

| Wastewater discharged into the municipal network (m3) | 1534.90 | 7215.60 | 14,767.20 |

| Hazardous waste (Mg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.39 |

| Non-hazardous waste (Mg) | 0.093 | 0.085 | 0.678 |

| Correlation matrix between selected financial data and indicators from 2017 to 2021 | Using observations 1–4 5% critical value (two-tailed) = 0.9500 for n = 4 | |||||

| v1 | v2 | v3 | v4 | v5 | ||

| 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | v1 | |

| 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | v2 | ||

| 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | v3 | |||

| 1.0000 | 1.0000 | v4 | ||||

| 1.0000 | v5 | |||||

| Correlation matrix between sales revenues in specific segments in 2017–2021 | Using observations 1–8 5% critical value (two-tailed) = 0.7067 for n = 8 | |||||

| v1 | v2 | v3 | v4 | v5 | ||

| 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.9998 | 0.9966 | 0.9973 | v1 | |

| 1.0000 | 0.9998 | 0.9966 | 0.9976 | v2 | ||

| 1.0000 | 0.9975 | 0.9976 | v3 | |||

| 1.0000 | 0.9946 | v4 | ||||

| 1.0000 | v5 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczepańczyk, M.; Nowodziński, P.; Sikorski, A. ESG Strategy and Financial Aspects Using the Example of an Oil and Gas Midstream Company: The UNIMOT Group. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813396

Szczepańczyk M, Nowodziński P, Sikorski A. ESG Strategy and Financial Aspects Using the Example of an Oil and Gas Midstream Company: The UNIMOT Group. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813396

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczepańczyk, Marta, Paweł Nowodziński, and Adam Sikorski. 2023. "ESG Strategy and Financial Aspects Using the Example of an Oil and Gas Midstream Company: The UNIMOT Group" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813396

APA StyleSzczepańczyk, M., Nowodziński, P., & Sikorski, A. (2023). ESG Strategy and Financial Aspects Using the Example of an Oil and Gas Midstream Company: The UNIMOT Group. Sustainability, 15(18), 13396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813396