Abstract

Urban renewal is a planning and renovation activity for cities, and pursuing cultural sustainability as a goal of urban renewal can expedite the achievement of high-quality and sustainable urban development. This paper uses the seven elements of cultural sustainability—Cultural Heritage (B1), Cultural Vitality (B2), Economic Vitality (B3), Cultural Diversity (B4), Place (B5), Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6), and Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7)—as the core indexes to develop a three-level indicator system applicable to cities with Chinese characteristics. The subjective–objective combination weighting method is then employed to assign weights to the indicators. Among them, Economic Vitality (B3) has the most significant weight, indicating that economic vitality significantly impacts the cultural sustainability of Chinese cities. In addition, the TOPSIS method was employed to assess typical Chinese cities. The assessment demonstrates that our cities can preserve cultural heritage, foster cultural vitality, attract a diverse population, and promote ecological civilization construction. The index system is exhaustive, the selection of indicators is appropriate, and the results of the practical application of the assessment are accurate and effective, allowing it to provide scientific planning guidance for urban renewal.

1. Introduction

According to the international urban development experience, the urbanization rate exceeding 60% will lead to urban disease [1]. Among them, urban disease refers to overpopulation, environmental pollution and insufficient carrying capacity, traffic congestion, social segregation, and other problems in the process of urban development, which will cause severe damage to the function of the city [2]. Furthermore, by the end of 2021, the urbanization rate of China’s resident population has reached 64.72% [3]. To avoid urban ills, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) pointed out in the “Twentieth National Congress” that China should accelerate the implementation of urban renewal [3]. Urban renewal refers to the planning and construction activities and systems of remediation, transformation, and redevelopment of urban built-up areas based on transforming urban industries, functional enhancement, and optimizing facilities. Urban renewal, as an essential way to realize cities’ high-quality and sustainable development, effectively reduces the harm of urban diseases [4].

Among them, the goal of urban renewal is the most critical aspect of urban renewal implementation to reveal the power source and effect results of renewal [5], and scholars have emphasized that the goal of urban renewal should be considered in an integrated and comprehensive manner [6]. China’s cities have entered a new phase of high-quality development that prioritizes connotation enhancement and quality. This stage emphasizes that urban development must shape a beautiful living environment and diverse public space, enhance public facilities, implement a green mode of transportation, and bolster cultural resources [7]. To promote the high-quality development of China’s cities, it is crucial to establish a comprehensive urban renewal objective [4].

As a vital resource and asset for urban development, culture can contribute to cities’ competitiveness and sustainability by providing social, economic, and spatial benefits [8]. The international community broadly acknowledges the sustainable development of culture as a critical indicator for measuring and promoting high-quality urban development [9]. Promoting the cultural sustainability of China’s cities is one of the essential objectives of China’s urban renewal at this stage, which positively impacts ensuring the high-quality development of China’s cities [7]. Hence, examining culture comprehensively in the urban renewal process and maximizing the benefits brought about by the sustainable development of culture.

Regrettably, the academic community has focused on urban renewal’s economic, environmental, and social goals, exploring its policies and sustainable development path [6], and rarely considers culture an independent goal. So targeted recommendations to improve China’s cultural sustainability in the city may need to be revised [10]. Urban renewal sometimes prioritizes commercial concerns and infrastructure investment over urban culture and culture [7,11], requiring heightened attention. This has produced problems such as blind development, homogenized urban culture, and the biological environment that sustains it disappearing [12]. Colombia, Florence, and London are developing urban cultural preservation zones with limited commercialization to conserve culture, people, and the environment [13]. Additionally, it may decrease community cohesion and social identity [14]. Traditional social relationships and cultural practices are gone, and residents need more urban decision-making power. Urban renewal enhances social inequality by creating economic disparities and reducing community cohesion and social identity [15]. Traditional social relationships and cultural practices are gone, and residents need more urban decision-making power. Then, should take a broad view of culture in urban renewal.

To address these issues and promote the cultural sustainability of cities, this paper aims to construct a cultural sustainability indicator system for China’s actual situation. Through this indicator system, the elements of cultural sustainability can be refined into quantifiable indicators to improve the efficiency of goal achievement and provide comprehensive guidance for planning and implementing urban renewal in China. At the same time, evaluating this system can provide scientific decision-making for promoting the protection and inheritance of culture in cities, promoting the development of cultural industries, and enhancing the image and attractiveness of cities to avoid urban diseases and cultural convergence among cities. We hope to stimulate the cultural vitality of cities. We also aim to promote the cultural growth and differentiation of cities to realize the high-quality and sustainable development of cities.

2. Literature Review

Science, policy, and the international community promote “cultural sustainability” The majority of academicians view it as preserving and promoting cultural heritage [16,17,18]. In contrast, others believe it also encourages cultural expression and vitality [19,20]. However, these conceptions are primarily concerned with cultural sustainability’s cultural effects and outcomes. Soini et al.’s seven elements of cultural sustainability—cultural heritage, vitality, economic vitality, diversity, place, eco-cultural resilience, and eco-cultural civilization, have rationalized, comprehended, and reconciled the concept [21]. Beyond culture, cultural sustainability promotes social, economic, and ecological sustainability [22,23].

The quantitative research and practical application of theory aim to develop a system of cultural sustainability indicators to measure and represent an object’s capabilities. For example, in Osman’s use of the seven elements of cultural sustainability, a system was devised to evaluate Ghana’s cultural sustainability [24]; Streimikiene et al. used only cultural vitality to compare the value created by culture in industrialized nations around the Baltic Sea [25]. In addition, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has proposed the “Culture 2030” metrics to assist nations in evaluating their cultural sustainability and policy outputs. Indicators that are measurable and rankable are required [26]. Most indicator systems are developed and utilized at the national and policy levels. No one considers and uses the indicator system’s scale and objective. Research must be expanded and refined.

China requires research on the cultural sustainability indicator system. Most researchers who study culture indicator systems focus on evaluating cultural industry development [27]. In city indicator systems such as the urban renewal assessment system [7] and the urban sustainability evaluation indicator system [28], culture is typically classified as social, resulting in unbalanced evaluation results and recommendations. In addition, the global academic community’s cultural sustainability indicator system is not universal and requires improved quantification [29]. Currently, the construction of the indicator system accentuates the need for a comprehensive examination of geographical distinctions and national requirements of countries to differentiate indicator design [30].

This paper aims to construct an indicator system based on seven elements of cultural sustainability and measure the cultural sustainability capacity of typical Chinese cities based on China’s actual situation and the goal of urban renewal. These elements can comprehensively evaluate the status of cultural sustainability [21]. They constitute a complex system that can accurately reflect the comprehensive impact of cultural sustainability. Moreover, we point out that these elements have great significance in China. China possesses a rich cultural heritage, diverse cultural vitality, rapidly growing economic vitality, rich cultural diversity, and the need to confront ecological challenges. Consequently, using these elements as the indicator system’s foundation will aid in understanding and assessing the status of cultural sustainability in the country and provide decision makers with a scientific foundation. In addition to enhancing quantitative research on cultural sustainability, this study can provide targeted guidance for urban renewal in China, which has specific application potential.

3. Indicators Development and Methods

3.1. Composition of Indicators

In this paper, the first-level indicator is named “BM”; the second-level indicator is named “CMN”; and the third-level indicator is named “DMN-O”. Where M = 1, 2, 3, …, n (n > 0); N = 1, 2, 3, …, n (n > 0); O = 1, 2, 3, …, n (n > 0). For example, “B2”, “C23”, and “D23-1” denote the No. 2 first-level indicator, the No. 3 second-level indicator of the No. 2 first-level indicator, and the No. 1 third-level indicator of the No. 3 second-level indicator of the No. 2 first-level indicator.

The proposal of the elements of cultural sustainability lays the foundation for constructing the indicator system and quantitative research. In this paper, we will take the seven elements of cultural sustainability: Cultural Heritage (B1), Cultural Vitality (B2), Economic Vitality (B3), Cultural Diversity (B4), Place (B5), Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6), and Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7) as the core indicators and combine them with China’s actual situation to establish an indicator system [21] and measure the corresponding capacity of Chinese cities.

3.1.1. Composition of Cultural Heritage (B1)

Cultural heritage, as a manifestation of the collective memory of human society and a non-renewable cultural resource, is a symbol of a city’s history and culture, which helps to maintain cultural groups and promote cultural identity, and makes an essential contribution to the sustainable development of the society, economy, and environment [28]. China’s cities have an abundant cultural heritage, including historical buildings, monuments, traditional arts, handicrafts, etc. To promote cultural sustainability in China’s cities, it is necessary to emphasize the protection and transmission of cultural heritage [31]. Evaluating the city’s cultural heritage protection status and historic building protection rate [32], cultural heritage tourism development [33], and other indicators to reveal the city’s ability to protect and pass on cultural heritage is an essential prerequisite and foundation for promoting the protection and inheritance of cultural heritage [34]. So far, this paper has constructed the following two second-level indicators, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Cultural Heritage (B1) and their interpretation.

3.1.2. Composition of Cultural Vitality (B2)

Cultural vitality is understood as the vitality, action, concentration, and continuity of culture, which can reflect the degree of excavation of cultural values, the competitiveness of culture and related industries, and the people’s sense of access to culture in the city, and also serve as evidence of the creation, dissemination, recognition, and support of culture and art by the society [34]. Cultural vitality is vital for promoting high-quality and cultural sustainability in cities [21]. Indicators of a city’s cultural vitality include the development of cultural and related industries, the richness of cultural resources and activities, and the scale of artistic performances and exhibitions. These indicators reflect the city’s cultural innovation ability, economic contribution, and the impact of cultural activities on the quality of life of urban residents. So far, this paper has constructed the following three second-level indicators, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Cultural Vitality (B2) and their interpretation.

3.1.3. Composition of Economic Vitality (B3)

Economic vitality refers to the ability and potential of economic development [43]. During the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan period, China is accelerating the construction of a new development pattern in which “the domestic macro-cycle is the mainstay, and the international and domestic double-cycle are mutually reinforcing” [44]. This indicator integrates the city’s economic growth rate and the amount of cultural consumption expenditure. It aims to reflect the level of urban economic development and the potential to guarantee cultural sustainability. So far, this paper has constructed the following two second-level indicators, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Economic Vitality (B3) and their interpretation.

3.1.4. Composition of Cultural Diversity (B4)

Cultural diversity refers to the many forms of different groups and societies and their cultural expressions, and it emphasizes respect and tolerance of differences between cultures [47,48]. Cultural diversity can promote economic growth, improve ecological quality, and guide people to lead a more fulfilling life intellectually, emotionally, morally, and spiritually. It is one of the primary sources of power for high-quality urban development and cultural sustainability [49]. China is a multi-ethnic country, and the cultural diversity of cities is reflected in the cultural differences between different ethnic groups and communities [50]. By examining the indicators of ethnic diversity, cultural exchanges, and integration degree of cities, we assess the city’s inclusiveness of multiculturalism and its ability to promote cultural exchanges [49]. So far, this paper has constructed the following nine second-level indicators, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Cultural Diversity (B4) and their interpretation.

3.1.5. Composition of Place (B5)

This indicator highlights regional culture and humanistic ideals, fostered by geography and natural resources [21]. Natural geography builds culture, which provides it social meaning [53]. This indicator discusses culture and natural geography. It describes regional people’s production, lifestyle, emotional attractions, and cultural representations [21]. Chinese cities are widespread and have distinct cultures. The assessment must evaluate the city’s regional cultural traits, cultural tradition heritage, etc. [60]. Thus, the city’s cultural uniqueness and ability to preserve and develop local qualities are exposed. This work has created two supplementary indicators, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Place (B5) and their interpretation.

3.1.6. Composition of Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6)

Ecological-cultural resilience refers to the linkage between ecology and culture, i.e., ecological stability is an essential prerequisite for cultural sustainability [21]. The monitoring of ecosystem trends and timely adjustment of countermeasures requires the use of natural and social knowledge. Thus, culture becomes the guarantee and driving force for the dynamic balance between human beings, their societies, and ecological nature, as well as for environmental management and governance [63]. From the perspective of systems thinking, ecological-cultural resilience should be known as the ability of ecosystems, infrastructures, and policy systems to recover their original structures and functions after being disturbed. Therefore, this paper constructs the following two second-level indicators, as presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6) and their interpretation.

3.1.7. Composition of Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7)

Ecological civilization shares more of its cultural connotations. System building, science, technology, human awareness, and ecological civilization action are included [66]. Cities and their environment are affected by global climate change and economic changes. The Chinese government uses socialist ecological PR to promote ecological civilization literacy and knowledge. Compatible with ecological civilization helps cultural sustainability, creating a great cultural environment [67]. Table 7 shows the two second-level indicators this article creates.

Table 7.

Composition of lower-level indicators for Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7) and their interpretation.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Methodology of Indicator System Construction and Indicator Development

This study constructs the indicator system top-down from the 7 first-level and 22 second-level indications interpreted and connoted above [71]. After experts and researchers create the study framework and indicator set, policymakers and the public make changes based on the ground situation [72]. Meanwhile, the three-level indicator database was built according to scientific, methodical, and adaptive indicator system architecture [73,74]. Supplementary Materials S1 shows the 179 third-level indicators developed. The indicator system in this article matches China’s national circumstances and urban development status quo. The quantitative metrics may direct urban renewal.

3.2.2. Methodology for Weighting Indicators

- Subjective weighting. In this paper, ANP is used to determine the subjective weights of the indicators, in which the underlying indicators are calculated as the second-level indicators, and the subjective weights of the first-level indicators are derived [75]. ANP is based on the traditional hierarchical analysis method (AHP), which further considers the interactions between factors or neighboring levels and utilizes the “supermatrix” to comprehensively analyze the interacting and influencing factors to derive their hybrid weights, which is currently widely advocated in the academic community [76,77]. Because of the indicator system constructed in this paper, there is a relationship of mutual influence between the indicators, so the assignment method is used. The specific operation is as follows.

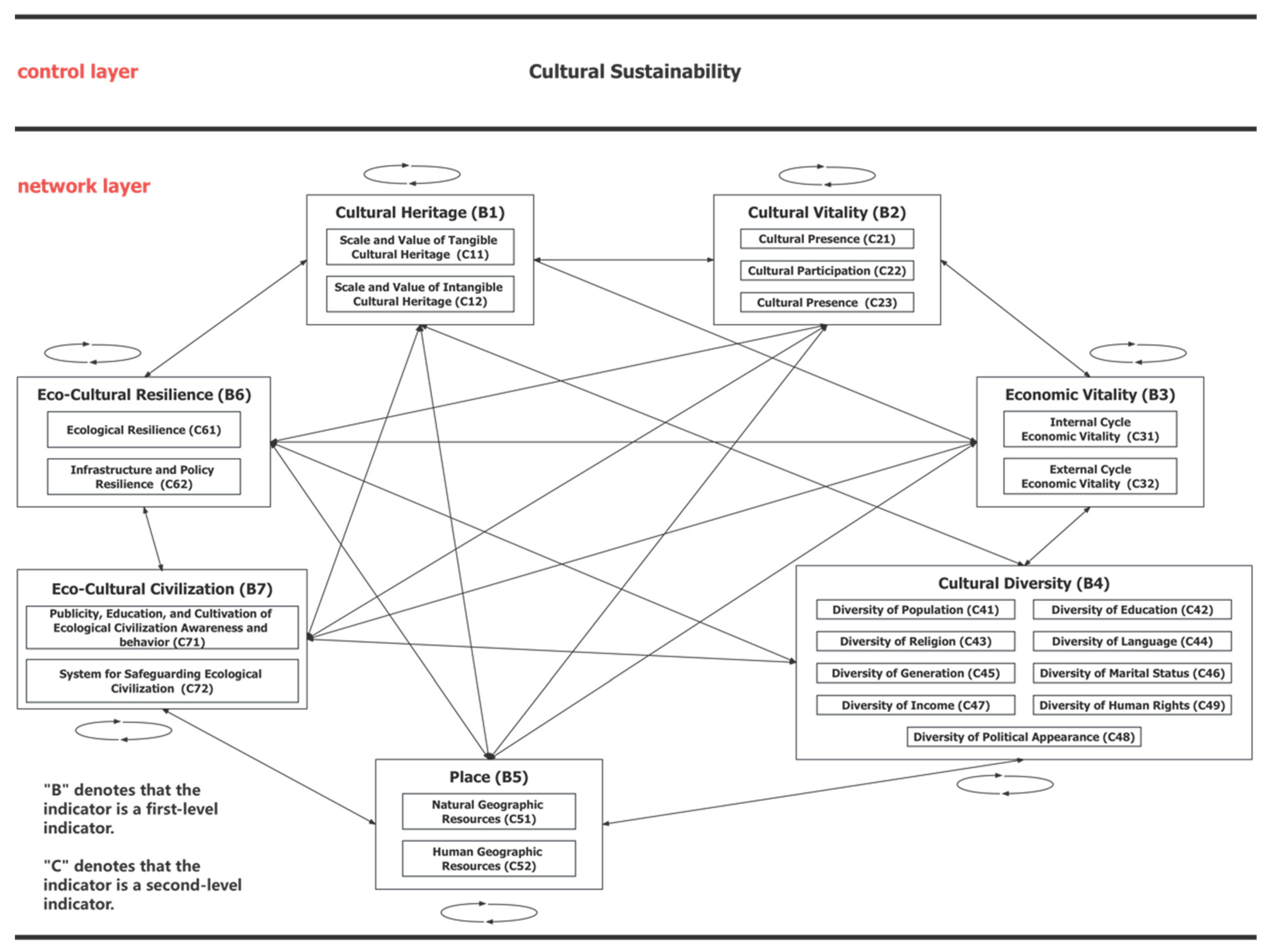

First, the network hierarchical structure is constructed in yaanp V2.6 software, as shown in Figure 1. In this paper, the constructed indicator system is divided into two layers: the first layer is the control layer, the main decision-making problem of the goal in this paper for cultural sustainability; the second layer is the network layer, that is, by the control layer governed by the various elements of the element groups and elements. Assuming that there are N element groups in the network layer, in this paper, the network layer element groups include Cultural Heritage (B1), Cultural Vitality (B2), Economic Vitality (B3), Cultural Diversity (B4), Place (B5), Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6), and Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7). The element group Bi has elements Ci1, Ci2, …, Cij, i = 1, 2, …, 7 constituted by the network level element group elements in this paper for 22 secondary indicators, i.e., C11 to C72.

Figure 1.

Network hierarchical structure of the seven indicators.

Subsequently, a research questionnaire was issued to ten experts to determine the correlation relationship with the completion of the indicator two comparisons [78]. Among them is the identity of each expert to meet the urban renewal subject composition, that is, the government, the market, and the public tripartite group. The specific identity includes government officials, market practitioners, and university scholars. The experts agreed that there is a mutual influence relationship between the first and second-level indicators of the indicator system.

Further, after inputting the data of each element group and element in the software, the weighted supermatrix is obtained by comparing element groups and elements two by two. Since the limit values converge and are unique when the self-multiplication operation is performed on the weighted supermatrix, the result obtained is the limit matrix. The global weight value of each second-level indicator, the local weight value of each second-level indicator, and the weight value of the first-level indicator are processed through the software operation. Finally, the results of the above operations are tested for consistency [78], and the subjective weights of the indicators are obtained, as shown in Table 8. It can be found that Economic Vitality (B3) has the highest subjective weight, indicating that ensuring the city’s economic vitality is crucial to the sustainable development of urban culture in China. Cultural Vitality (B2) and Cultural Diversity (B4) rank second and third, respectively.

Table 8.

Results of the calculation of the subjective weights of the first-level indicators.

- Objective weighting. This study determines indicator objective weights using Entropy Weight. The method determines indicator weights based on indicator data, which the more information an indicator gives, the more critical and weightier it is in the assessment [79]. Entropy Weight avoids subjective human influences in the subjective assignment method and weights a comprehensive volume indication system [80]. Since the three-level indicators in this work are quantifiable, the method approach is employed to calculate their objective weights first, and then calculate the objective weights of the second and first-level indicators [79,80]. The operation is as follows: First, the three-level indications are positive and negative. The more extensive positive signs with benefit qualities, the better, and the more minor negative indicators with cost attributes, the better. Supplementary Materials S1 lists 16 negative signs in this paper’s indicator system. Since there are more positive indications, the majority rule processes all indicators as positive. Larger indicator values better represent the scenario. The indications are then processed consistently and dimensionless. This paper’s dimensionless indicator approach prevents direct comparison of evaluation indicators due to their diverse scales and kinds. Results from objective weight computation are in Table 9. Economic Vitality (B3) has the most significant objective weight and a cumulative number of top places in the statistical year, confirming that it helps preserve urban culture in China.

Table 9. Results of the calculation of the objective weights of the first-level indicators.

Table 9. Results of the calculation of the objective weights of the first-level indicators.

- Combined weighting. Although ANP represents experts’ judgment of indicator value, it includes subjective solid human aspects since it uses their expertise to determine indicator weights [81]. The Entropy Weight approach completely utilizes indicator data information differences to calculate indicator weights, and it just shows the objective weight values, not the relevance of each indication [73]. Both methods require additional detail. To tackle this challenge, the contemporary academic community for indicator assignment increasingly uses a mix of assignment methods, which may use subjective and objective assignment methods to determine weights [82]. It may express the relevance of information, differentiate data assessment, minimize information loss, make each indicator’s weight more reasonable and objective, and better show the actual evaluation issue [73]. This paper synthesizes ANP, the Entropy Weight method of the indicator weights, to determine the combined weights and specific steps, such as the subjective assignment method for the second-level indicator weights and the objective assignment method for the third-level indicator weights. The minimal information entropy concept is employed to create the function for the indicator combination weights, and the Lagrange Multiplier approach is used to optimize [83]. Table 10 shows that after calculating the combined weights of each level of indicators, the higher objective weights of Economic Vitality (B3), Cultural Vitality (B2), and Cultural Diversity (B4) indicators in the statistical year due to over-reliance on sample data are weakened to optimize the weights of the rest of the indicators. The combination weights are more significant than the goal weights, indicating more stability. This shows that the combined weights are more reasonable and objective than the objective weights and confirms the critical role of Economic Vitality (B3), Cultural Vitality (B2), and Cultural Diversity (B4) in the sustainable development of urban culture in China. The combined weights are better for judging China’s cities’ cultural development capability than the subjective and objective weights.

Table 10. Results of the calculation of the combine weights of the first-level indicators.

Table 10. Results of the calculation of the combine weights of the first-level indicators.

3.2.3. Methodology for Sample Selection

To verify the validity of the index system constructed in this paper, this paper takes a typical city in China as an example to measure its capacity for cultural sustainability. In this paper, four municipalities in China, namely Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing, were selected for data collection based on the consistency and equivalence of the size of the cities, population size, administrative level, degree of development, and geographical distribution. The data were collected from 2015 to 2020 and mainly from the national economic and social development statistics, ecological environment bulletin, annual report of municipal government, etc. Some of the indicator data were collected by relying on the “Baidu Index” platform to obtain keyword searches as the indicator data [84]. For the missing data of some indicators, the data of the newest year were used as a substitute.

3.2.4. Methodology for Assessment Rationale

The TOPSIS method, which approximates the ideal solution, is used to rank the sample cities’ cultural sustainability capacity in the statistical year of data to reflect their differences and be used for subsequent analysis [84]. This ranking algorithm approximates the optimum answer. It ranks assessment items by finding the gap between the ideal and worst solutions, evaluates programs objectively under numerous indications, and adds the evaluator’s subjective choice. Before employing this approach, compute the distance between each assessment item, the best and worst solutions, and their relative progress. After the relative affixing progress, each evaluation object’s advantages and disadvantages are determined by its relative proximity, which is the interval for [0, 1]—the closer to 1, the better, and vice versa for the worst. Supplementary Materials S2 shows the calculation processes.

4. Assessment

According to the comprehensive weights of the constructed indicator system, this paper employs the TOPSIS method to calculate the relevant indicator data of the sample cities and rank their capability, level, and status of cultural sustainability. The ranking results are then used to analyze the sample cities’ problems and deficiencies in cultural sustainability. The assessment results are presented in Table 11, which reveals that from 2015 to 2020, the ranking of the sample cities’ cultural sustainability remained constant at the following positions: Beijing is superior to Shanghai, Chongqing, and Tianjin.

Table 11.

Overall and first-level indicator scores for cultural sustainability in sample cities.

4.1. Assessment Analysis

- Analysis of Cultural Heritage (B1). In the statistical years, ranking the capacity of the sample cities in the indicator has always remained the same: Beijing > Shanghai > Chongqing > Tianjin.

Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing are renowned for their cultural and historical significance. Beijing has been a dynasty capital, political and economic hub, and repository of cultural relics since antiquity. The region has developed cultural and creative products while preserving its cultural heritage. Modern design and traditional cultural elements have produced numerous outstanding cultural and creative products for cultural heritage [85]. The cultural derivatives of the Forbidden City Museum, such as treasures, clothing accessories, souvenirs, and artworks, are popular nationwide [86]. Cultural heritage and the cultural industry benefit from producing such creative and cultural products.

Tianjin lacks the wealth, history, and continuity of tangible and intangible cultural heritage, as well as economic and cultural values, compared to the other three cities, and its development and protection must be enhanced. Thus, the evaluation and ranking reflect reality.

- Analysis of Cultural Vitality (B2). Between 2015 and 2016, and 2018 and 2019, the sample cities in the indicator capacity ranking were Beijing > Shanghai > Chongqing > Tianjin; in 2017 and 2020, the ranking was Shanghai > Beijing > Chongqing > Tianjin, Beijing > Chongqing > Shanghai > Tianjin, respectively.

Since 2018, Beijing, the country’s cultural hub, has hosted numerous events centered on the Winter Olympics. These include art exhibitions, concerts, theatrical performances, and traditional cultural activities that attract domestic and international tourists [87]. Beijing has also established and utilized new cultural spaces, such as the 798 Art District, which have become hubs for the creative industries and artists, attracting art enthusiasts and practitioners [88]. Early in 2020, Beijing led “Organic Urban Renewal” and “Cultural Construction of the Capital”, revitalizing old buildings and neighborhoods to bolster culture [89].

As the economic hub of China, the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee and Municipal Government issued the “50 Articles of Shanghai Culture and Creativity” in 2017 [90]. These policies protect intellectual property, finances, talent development, and other areas, thereby promoting the growth of cultural and creative enterprises. This systematically improves Shanghai’s policy guarantee system for the cultural and creative industries and converts cultural resources into industrial advantages. In recent years, Shanghai has established cultural and creative industry parks in Jing‘An and Yangpu, among other urban areas [88]. These parks’ offices and spaces attract cultural and creative businesses, fostering innovation and collaboration. At the same time, the ‘Ju Fu Chang’ (Julu Road, Fumin Road, Changle Road) neighborhood, which is very characteristic of local culture, is home to many famous cultural and creative enterprises at home and abroad, such as WWD CHINA and LABELHOOD, etc. [91]. As Shanghai’s most commercially vibrant neighborhood, it still nurtures local cultural brands. Government and private organizations in Shanghai host numerous cultural events and festivals. Opening ceremonies for the China Shanghai International Arts Festival, Shanghai Music Festival, Shanghai Coffee Festival, etc. [92,93]. These events enrich the public culture and promote the culture of the community.

- Analysis of Economic Vitality (B3). In the statistical years, ranking the capacity of the indicator shows an alternating cycle, i.e., in odd-numbered years: Beijing > Shanghai > Chongqing > Tianjin, and in even-numbered years: Shanghai > Beijing > Chongqing > Tianjin, it can be seen that Beijing and Shanghai are the best performers in the ranking of Economic Vitality (B3), followed by Chongqing, and the poorest performance is Tianjin.

Beijing and Shanghai, in terms of the total amount of internal circulation economy, are almost alternately leading in terms of both total size and growth rate, and the two go hand in hand as the head cities in China. It is worth noting that in 2020, the economic volume of Shanghai, as China’s economic, finance, trade, shipping, science, and technology innovation center, is still in the upper reaches of the country despite its growth rate being hit by the impact of the epidemic. Its economic volume, financial strength, stable sources of income, and financial self-sufficiency [94] are consistent with the actual situation.

- Analysis of Cultural Diversity (B4). In the statistical years, ranking the capacity of the sample cities in the indicator remains the same: Shanghai > Beijing > Chongqing > Tianjin.

Due to their development and openness, Shanghai and Beijing have attracted large populations, creating regional cultural diversity. Shanghai, China’s most internationalized city, attracts many immigrants, international students, and expatriates. Social groups in Shanghai include residents, migrant workers, and returnees. Social groups in Shanghai include residents, migrant workers, and returnees. Shanghai attracts global business elites and multinational corporations as one of China’s major financial and business centers. Shanghai’s cultural diversity comes from these diverse cultures’ values, lifestyles, and social customs. Beijing, China’s capital and center of education and research, attracts many people. Beijing, China’s capital and education and research center, attracts people from abroad.

The Chongqing population includes residents, foreigners, and ethnic minorities. Chongqing’s cultural diversity is enhanced by ethnic minorities such as the Tujia and Miao, who live in the mountains. In addition, Chongqing, Southwest China’s economic and transportation hub, attracts much talent, increasing social diversity.

Tianjin’s cultural diversity is weaker due to its proximity to Beijing, which has attracted many locals [95]. This indirectly reduces cultural diversity, and the assessment results match.

- Analysis of Place (B5). In the statistical years, ranking the capacity of the sample cities in the indicator has remained consistent: Chongqing > Beijing > Shanghai > Tianjin.

Chongqing is in southwest China at the mountains and the Yangtze confluence. This location provides Chongqing with natural landscapes such as mountains, valleys, odd landforms, and local customs. This climate is ideal for the mountain city and Bayu cultures of Chongqing. Chongqing’s folklore, cuisine, and architecture developed in response to these natural environments. Chongqing’s humid climate and abundance of aquatic resources, for instance, produce spicy hot pots and the region’s signature bases and seasonings. Both Chinese and international tourists adore Chongqing’s hotpot culture. The hotpot is emblematic of Chongqing’s cuisine culture. It allows locals and tourists to recall fond memories.

Shanghai, located on China’s eastern coast, is at the center of the Yangtze Delta. Shanghai’s location makes it a crucial port and foreign exchange center. Due to its abundant aquatic resources, Shanghai’s cuisine emphasizes tenderness and a light flavor. Famous crab buns and xiaolongbao from Shanghai are seafood and river food. In addition to attracting foreign culture and commerce, Shanghai’s openness and geographic advantage have fostered internationalization. Globalization and cultural convergence have shaped Shanghai’s unique and diverse culture. In this article, place characteristics have been diluted. Nonetheless, it promotes cultural diversity and a harmonious mix of local and international cultures, which is equally essential.

- Analysis of Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6). In the statistical years, ranking the capacity of the sample cities in the indicator has remained the same: Chongqing > Shanghai > Beijing > Tianjin.

Due to its location in the Yangtze River’s main channel and its abundant natural resources, the ecological environment in Chongqing’s central district is favorable. The local government also enacted the Chongqing Water Pollution Prevention and Control Regulations, which went into effect on October 1, 2020, to strictly protect and manage Chongqing’s water environment, regulate water pollution, and safeguard local water quality [96].

Since Shanghai’s rapid economic and social development in the 1920s, a significant amount of domestic and industrial wastewater has been discharged into the river, causing Suzhou Creek to have a foul odor. In the late 1970s, the urban section of Suzhou Creek in Shanghai was permanently black and smelly, and fish and prawns were extinct, making it a significant urban environmental issue. Since 1998, the Comprehensive Environmental Improvement Management Measures for Suzhou Creek in Shanghai have regulated water activities and pollutant discharge within the scope of improvement [97]. Shanghai has followed the “water management as the focal point, comprehensive planning” model for the past three decades, altering Suzhou Creek. By 2020, each side of Suzhou Creek will have 42 km of coastline [98]. The construction of Suzhou Creek has created “a river and a river” waterfront public space for business, livability, recreation, and tourism, a prototypical megacity demonstration area. This significantly improves the ecological, cultural, and resiliency of the city.

Due to their location in the North China Plain, unfavorable weather, seasonal pollutant emissions, and other factors, residents of Beijing and Tianjin have struggled to prevent and control air pollution. Since 2012, Beijing has been closely monitoring emissions and wastes to meet local air quality standards by 2021 [99], and the current situation corresponds to the target data.

Tianjin has superior natural conditions to Beijing, such as coastal marshes. Beijing has a smaller gap between local integrated pollution management, ecological protection, and climate change adaptation. Since 2017, Tianjin City has conducted periodic ecological and environmental protection inspections in sensitive areas, regions, and industry organizations [100]. Locals actively advocate for the protection of the environment and the adoption of a low-carbon lifestyle. Thus, the indicator for Tianjin improved. Knowledge of policy and management is also necessary for environmental protection and urban sustainability.

- Analysis of Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7). Ranking the capacity of the sample cities in the indicator is dynamically changing during the statistical year. However, on a comprehensive basis, the performance of Shanghai and Beijing is relatively outstanding.

Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing promote education and regulation regarding ecological civilization. These cities promote ecological civilization through government-sponsored publicity, media reports, community education, and school curriculums.

Beijing has incorporated ecological civilization into its economic, social, and cultural development since its bid for the 2015 Winter Olympics [101]. This integration has accelerated the capital’s high-quality infrastructure development and increased residents’ awareness of ecological civilization. Thus, measurement results correspond to actuality.

Moreover, these four cities have enhanced ecological civilization oversight—implementing monitoring and enforcement systems and increased penalties for environmental violations. Beijing has implemented stricter air pollution regulations and banned fireworks and firecrackers. Shanghai encourages public environmental oversight. Since July 2019, Shanghai has also implemented a garbage classification system to increase citizens’ environmental awareness [102]. Tianjin has strengthened enterprise discharge oversight [99]. A comprehensive environmental monitoring system and active water environment management have enhanced water quality in Chongqing [95]. These initiatives encourage environmental protection, sustainable development, and cultural sustainability.

4.2. Assessment Result

- The indicator system is well designed, and the evaluation is accurate and reliable.

First, based on the requirements of China’s urban development at the current stage, this paper takes cultural sustainability as the goal of urban renewal. It constructs a three-level indicator system with seven latitudinal elements: Cultural Heritage (B1), Cultural Vitality (B2), Economic Vitality (B3), Cultural Diversity (B4), Place (B5), Eco-Cultural Resilience (B6), and Eco-Cultural Civilization (B7). On this basis, the subjective–objective combination assignment method was applied to determine the weights of the indicators so that they could reflect the experience of experts and the data characteristics. Among them, Economic Vitality (B3) has the highest combined weight value, reflecting that economic vitality plays an essential role in the cultural sustainability of China’s cities and should be emphasized.

Second, based on the constructed indicator system and weighting results, the TOP-SIS method assesses the cultural sustainability ability of four cities: Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing. The ranking reveals that Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing are cultural powerhouses that excel in heritage preservation, cultural vitality, economic performance, and eco-cultural initiatives. At the same time, Tianjin lags in these aspects. The results show that this indicator system is consistent with the actual situation and can be applied practically to know the construction of China’s urban renewal and cultural sustainability.

- 2.

- The sample cities are adept at preserving cultural heritage, fostering cultural vitality, attracting a diverse population, and advancing ecological civilization.

First, these cities have a balance between cultural preservation and development. Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing promote cultural innovation and development while preserving and transmitting cultural heritage.

Secondly, these cities are culturally vibrant and diverse. Beijing and Shanghai’s thriving cultural events and diverse populations enrich their cultures, among which Shanghai’s geographical advantage, which encourages internationalization, is vital for cultural exchange and integration.

Then, these cities actively protect the environment. Chongqing has effective environmental protection measures and favorable ecological conditions, whereas Shanghai is working to restore the Suzhou River. Beijing and Tianjin struggle to control air pollution, but they promote ecological civilization through education, regulations, and environmental initiatives.

Therefore, to further enhance the cultural sustainability capacity of the four cities, this paper puts forward the following suggestions for each of the four cities with the goal of urban renewal in Table 12.

Table 12.

Culture sustainability assessment results and recommendations for sample cities.

5. Conclusions

This paper develops a three-level indicator system with seven cultural sustainability elements to promote the cultural sustainability of Chinese cities at their current development stage. After quantifying the indicator system with the subjective–objective assignment method, the TOPSIS method is utilized to assess the cultural sustainability of typical Chinese cities. Scientific principles guide urban renewal. These are the conclusions:

- The indicator system applies to the Chinese environment.

First, it can evaluate the city’s cultural resources and heritage, essential for urban revitalization planning. Second, it balances cultural and economic vitality to guide urban renewal projects’ economic and cultural sustainability. Moreover, the indicator system emphasizes ecology and culture, integrating ecological and environmental protection with urban revitalization and cultural sustainability.

By emphasizing national characteristics, the system can better meet China’s cultural status and development requirements, provide scientific assessment tools and decision-making support for cultural sustainability in various regions of China, promote the protection, inheritance, and innovation of Chinese culture, and achieve the harmonious development of the economy, ecology, society, and culture.

- 2.

- Chinese cities’ cultural sustainability capacities vary and are shared.

China’s cities have diverse cultural sustainability capacities due to their diverse historical, geographical, and cultural backgrounds. This includes cultural preservation, inheritance, industry development, and international cultural exchanges.

Regardless of their size, our cities prioritize preserving and transmitting their rich cultural heritage, stimulating public interest and participation in culture, combining cultural resources with economic development, promoting multicultural exchanges and integration, and integrating culture and the natural environment. These features reflect the global significance and cultural sustainability collaboration of cities.

In addition, a combination of factors contributes to differences and standard characteristics in cultural sustainability capacity. These include the city’s historical heritage and cultural resource base, urban planning and management capacity, government support, and cultural policies. These factors’ weight and degree of influence vary from city to city, resulting in varying cultural sustainability capacities.

Through cultural heritage protection, our government has actively encouraged cities to protect their cultural heritage, stimulate cultural vitality, develop cultural industries, promote multicultural exchanges and integration, and integrate ecology and culture. They can increase the prosperity and sustainability of their cities by enhancing their cultural sustainability capacities.

6. Discussion

This paper presents an indicator system that highlights domestic characteristics, integrates closely with Chinese cultural traditions and traits, and has a strong practical orientation. It offers a comprehensive framework for evaluating cultural sustainability, considering cultural heritage, cultural vitality, economic vitality, cultural diversity, and other factors.

Nonetheless, the indicator system has limitations. For instance, the volume of the indicator system is excessively high. This further complicates the collection of indicator data and the calculation of indicator weights. The selection of indicators and measurement criteria must be further optimized. Moreover, due to the complexity and diversity of culture, this system may only be able to encompass some aspects of consideration. The digital development and cultural experience in China have gradually become an indicator that must be addressed, as revealed by our research. In the future, the evaluation needs of the indicator system will be supplemented and expanded, which will also be the determining factor for the success or failure of the indicator system.

Lastly, the direction of future research can be expanded to include the applicability of various types of Chinese cities, such as China’s active rural revitalization. The indicator system is applicable at the municipal, county, and municipal levels. Additionally, cross-country comparisons and the exchange of knowledge can be investigated. In conclusion, the indicator system is valuable for ensuring cultural sustainability but requires further development and expansion.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su151813571/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G. and C.L.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.G.; validation, Y.G., C.L. and H.G.; formal analysis, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant numbers 2232023G-08 and 2232021E-03.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kong, C.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Run, H. The urbanization history of representative developed countries and its revelations. Macroecon. Manag. 2021, 11, 39–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Measurement Index System and Empirical Analysis of China’s Urban Diseases. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Renewal: China in Action. Available online: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2023-01/02/content_25957262.htm (accessed on 3 January 2023). (In Chinese).

- Chen, H.; Lai, Y. Decision-making in the Stock-based Urban Renewal Process in Shenzhen City: A Perspective from Spatial Governance. Urban Plan. Forum 2021, 11, 61–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Wu, B. Construction of the Theoretical Framework for Inclusive Urban Renewal. Constr. Econ. 2020, 41, 109–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Deng, Y. Spatio-temporal evolution path and driving mechanisms of sustainable urban renewal: Progress and perspective. Prog. Geogr. 2021, 40, 1942–1955. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, W. Study on the Evaluation of the Comprehensive Benefits of Urban Renewal Actions in the New Era. Soc. Sci. Hunan 2022, 6, 84–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dessein, J.; Soini, K.; Fairclough, G.; Horlings, L.; Battaglini, E.; Birkeland, I.; Duxbury, N.; De Beukelaer, C.; Matejić, J.; Stylianou-Lambert, T.; et al. Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development: Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability, 1st ed.; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015; pp. 18–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, N.; Chithra, K. Role of culture in sustainable development and sustainable built environment: A review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5991–6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Qian, X. The spatial production of simulacrascape in urban China: Economic function, local identity and cultural authenticity. Cities 2020, 104, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X. Model of Transformation on Urban Renewal in China: From “Economy Old City Reconstruction” to “Social Urban Renewal”. Urban Dev. Stud. 2015, 22, 111–116+124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Development Should Not Cut off the Historical Lineage. Available online: http://www.qstheory.cn/qshyjx/2020-12/24/c_1126901820.htm (accessed on 24 December 2020). (In Chinese).

- UNESCO; World Bank. Cities, Culture, Creativity: Leveraging Culture and Creativity for Sustainable Urban Development and Inclusive Growth, 1st ed.; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 05–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stimulating Cultural Vitality for Urban Renewal. Available online: https://www.drc.gov.cn/DocView.aspx?chnid=386&leafid=1339&docid=2903667 (accessed on 23 July 2021). (In Chinese)

- Lu, S. The Problem of Whether There Is Discontinuation after the Emergence of a Legal Dangerous State. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2012, 20, 68–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Theoretical Research on the Sustainable Development of Musical Culture of Minority Ethnic Groups. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2017, 38, 116–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Ouzhu, N. A Discussion on the Sustainable Development of Tibetan Traditional Sports Culture. J. Tibet. Univ. 2013, 28, 50–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukadari, S.; Huda, M. Culture sustainability through Co-curricular learning program: Learning Batik Cross Review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.A.; Turner, R. Cultural sustainability: A framework for relationships, understanding, and action. J. Am. Folk. 2020, 133, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titon, J.T. Music and sustainability: An ecological viewpoint. World Music 2009, 51, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packalén, S. Culture and sustainability. Spec. Issue Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.H. Build Capacity for International Health Agenda on the “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. Health Policy Manag. 2015, 25, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A. Empirical measure of cultural sustainability. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 145, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Mikalauskiene, A.; Kiausiene, I. The Impact of Value Created by Culture on Approaching the Sustainable Development Goals: Case of the Baltic States. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture|2030 Indicators, 1st ed.; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 10–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y. High-quality Development of Cultural Industry: Construction of Evaluation Index System and Its Policy Significance. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 147–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Chen, S.; Gao, J.; He, Y.; Zhou, H. Design of China’s sustainable development evaluation index system based on the SDGs. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Lin, J. Review of Decision-making Support Methods of Sustainable Urban Renewal. Areal Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 59–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Liu, L.; Zhao, X. Study on Indicator System of World Modernization. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2020, 35, 1373–1383. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Huang, Y. The digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage in China: A survey. Preserv. Digit. Technol. Cult. 2019, 48, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, F.; Ma, Y. Network construction for overall protection and utilization of cultural heritage space in Dunhuang City, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, M. Intangible cultural heritage in tourism: Research review and investigation of future agenda. Land 2022, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.R.; Kabwasa-Green, F.; Herranz, J. Cultural Vitality in Communities: Interpretation and Indicators, 1st ed.; The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 4–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Chen, F. Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage and national cultural development strategies. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2008, 4, 81–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X. Evolutionary characterization and quantitative evaluation of red tourism policy. Stat. Decis. 2023, 16, 64–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lin, B.; Cheng, X. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of national intangible culture heritage in China. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2023, 39, 949–956. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Deng, Y. Imagery Pattern of Intangible Cultural Heritage Landscape Gene Mining—In Hunan Province. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 185–192. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z. Cultural Participation Mechanism: Institutional Provision of Public Cultural Service Construction—Taking Yinzhou District of Ningbo City as an Object of Analysis. Study Pract. 2012, 7, 122–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Černevičiūtė, J.; Strazdas, R.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Stimulation of cultural and creative industries clusters development: A case study from China. Terra Econ. 2019, 17, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Wang, Q. Cultural and creative industries and urban (re) development in China. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. Study on Urban Economic Vatality Index in China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2007, 1, 9–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. On the New Pattern of Regional Economic Development under Double Circulation—And on the Constant Running Trend during the ”14th Five-Year Plan” and Two Planning Periods after It. Rev. Econ. Manag. 2021, 37, 23–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Han, Z. Comparative Research on Statistical Measurement of City Vitality. World Surv. Res. 2021, 8, 74–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhao, J. The Effect and Path of Innovation-Driven Economic Internal Circulation. Reform Econ. Syst. 2022, 1, 195–200. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fearon, J.D. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijamampianina, R.; Carmichael, T. A pragmatic and holistic approach to managing diversity. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2005, 3, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Betzler, D. Implementing UNESCO’s Convention on Cultural Diversity at the regional level: Experiences from evaluating cultural competence centers. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2020, 27, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hong, F.; Yin, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, G.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Cui, C.; Li, X.; CMEC. Cohort Profile: The China Multi-Ethnic Cohort (CMEC) study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X. The Regional Difference and Convergence of Urban Population Size in China. Popul. J. 2021, 43, 5–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Feng, J. Clarification and Research Progress of Various Urban Spatial Concepts. Urban Dev. Stud. 2020, 27, 62–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Junxi, Q.; Hong, Z. Theoretical unity and thematic diversity in new cultural geography. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview of religions in China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/test/2005-06/22/content_8406.htm (accessed on 1 December 2022). (In Chinese)

- Mazur, B. Cultural diversity in organisational theory and practice. J. Intercult. Manag. 2010, 2, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X. Analysis of the Root Causes of the Aging Digital Divide and the Construction Strategy of a Digital Inclusive Society. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 24, 94–101+112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. The Research on the Transformation of the Society and the Changing of Values on Family and Marriage. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, H.; Dan, Z. The Changing Trend of Income Elasticity of Cultural Consumption in China. Econ. Rev. J. 2021, 9, 80–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G. Multiple Modernities and the Logic of Political Development from the Perspective of “Sociology of Democracy”. J. Xiamen Univ. (Arts Soc. Sci.) 2022, 72, 118–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, X.; Qian, J. Charting the development of social and cultural geography in Mainland China: Voices from the inside. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 15, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Tao, L.; Mingfang, T.; Hongbin, D. Spatial pallerns of bioculural diversily in Southwest China. Acla Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 2454–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Regional cultures in the age of globalization. Dushu 2010, 11, 59–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. Resilient urban forms: A macro-scale analysis. Cities 2019, 85, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongyue, L.; Pinyi, N.; Chaolin, G. A Review on Research Frameworks of Resilient Cities. Urban Plan. Forum 2014, 5, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z. Ecological Civilization in China: Challenges and Strategies. Capital. Nat. Social. 2021, 32, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gare, A. The Eco-socialist Roots of Ecological Civilisation. Capital. Nat. Social. 2021, 32, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, J. Measuring and Defining Eco-civilization Cities in China. Resour. Sci. 2013, 35, 1677–1684. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection from the Perspective of Building an Ecological Civilization. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 35, 58–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Zuo, T. Ecological civilization and government administrative system reform in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 155, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Experiences with sustainability indicators and stakeholder participation: A case study relating to a ‘Blue Plan’ project in Malta. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, X. Conditional characteristic evaluation based on G_2-entropy weight method for low-voltage distribution network. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2017, 37, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choon-Piew, P. Building a harmonious society through greening: Ecological civilization and aesthetic governmentality in China. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 864–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Luan, S. The exposition of measure and indicators of sustainable development. World Environ. 1996, 1, 7–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making—The analytic hierarchy and network processes (AHP/ANP). J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2004, 13, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jharkharia, S.; Shankar, R. Selection of logistics service provider: An analytic network process (ANP) approach. Omega 2007, 35, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, X.; Ding, X.; Gao, C. Evaluation of sustainable competitiveness of textile and costume industry based on analytic network process theory. J. Text. Res. 2018, 39, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Duan, X.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y. Empowering High-Quality Development of the Chinese Sports Education Market in Light of the “Double Reduction” Policy: A Hybrid SWOT-AHP Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Wu, G.; Ji, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Gao, T. Evaluation of provincial carbon neutrality capacity of China based on combined weight and improved TOPSIS model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, M. Research on a Combined Method of Subjective-Objective Weighing and the Its Rationality. Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 17–26+61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. A hybrid multi-criteria decision-making approach based on ANP-entropy TOPSIS for building materials supplier selection. Entropy 2021, 23, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Zhou, R.; Tian, H.; Xu, D.; Xu, W. Assessment of Distribution Network Scheduling Level Based on Combined Weight-TOPSIS. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2023, 35, 95–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Li, M.; Tian, F.; Wu, R.; Yang, Q. Distribution Pattern and Driving Mechanism of Network Attention of Chinese Red Tourism Classic Scenic Spots. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 211–220. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. Development Design and Promotion of Beijing Palace Museum Cultural Creative Products under the Background of “Internet +”. Packag. Eng. 2021, 41, 309–312+316. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Forbidden City Cultural Creation Branding in This Way Various Ways to Spread Excellent Traditional Culture. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2019-03/01/c_1124177901.htm (accessed on 1 March 2019). (In Chinese).

- Beijing Winter Olympics: Cultural Heritage and Global Communications. Available online: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmlt/html/2022-08/20/content_25947263.htm (accessed on 29 August 2022). (In Chinese).

- Zhou, S.; Yang, H.; Kong, X. The structuralistic and humanistic mechanism of placeness: A case study of 798 and M50 art districts. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Guiding Opinions of the Beijing Municipal People’s Government on the Implementation of Urban Renewal Actions. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-06/10/content_5616717.htm (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Shanghai’s “Article 50 on Cultural and Creative Industries”: Building an International Cultural and Creative Center. Available online: http://m.xinhuanet.com/2017-12/17/c_1122123642.htm (accessed on 17 December 2017). (In Chinese).

- Jing’an Speeds up Urban Renewal with Four Major Construction Projects. Available online: https://en.imsilkroad.com/p/334083.html. (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Festive and Tourism Activities for Every Season. Available online: https://www.shanghai.gov.cn/nw48081/20230523/52c210c6d123406ab285611f35cd6b9d.html (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Events in Shanghai. Available online: https://10times.com/shanghai-cn (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Statistical Bulletin on the National Economic and Social Development of Shanghai Municipality in 2020. Available online: https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/201805/16/WS5ce79f70498e079e68021a8e/events-in-shanghai.html (accessed on 19 March 2021). (In Chinese).

- Shi, M. Study on the Changing Characteristics of Population Growth in Tianjin and Its Impact. City 2019, 11, 45–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chongqing Water Pollution Prevention and Control Regulations. Available online: http://nyncw.cq.gov.cn/xxgk_161/zfxxgkzl/fdzdgknr/zcwj/dfxfg/202207/t20220727_10956942_wap.html (accessed on 27 July 2022). (In Chinese)

- Suzhou Creek Remediation Project. Available online: http://bmxx.swj.sh.gov.cn/SZH_proj/zhzz/zhzz/gs.html (accessed on 13 July 2023). (In Chinese)

- Transforming the Riverside. Available online: https://www.chinadailyasia.com/article/155746 (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Beijing’s Air Quality to Fully Meet Standards for the First Time in 2021. Available online: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/gongkai/shuju/sjjd/202201/t20220105_2582724.html (accessed on 5 January 2022). (In Chinese)

- Inspection and Rectification to See Results—Tighten the Responsibility of the “Screws” to Change the Long-Term Governance of a Long Time Clear. Available online: http://sthjt.hubei.gov.cn/hjsj/ztzl/sthjbhdc/tszs/202208/t20220829_4283924.shtml (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- People’s Daily: Carbon Neutral Winter Olympics: The World Moves toward a Green Future Together. Available online: http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0221/c437949-32356422.html (accessed on 21 February 2022). (In Chinese).

- China Focus: Garbage Sorting Games in Shanghai Win Hearts of Young People. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/02/c_138190043.htm (accessed on 2 July 2019).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).