Abstract

(1) Background: In recent years, post-90s employees have emerged as the driving force behind enterprise innovation, presenting unique challenges for innovation management. Their distinct characteristics and attitudes towards work require a thoughtful and adaptable approach from businesses to harness their potential effectively; (2) Methods: through empirical analysis of 518 valid samples in the Chinese context, with SPSS 26.0 and PROCESS V4.1 being used for the analysis, and to test the moderated mediation model; (3) Results: a. Mentoring relationships positively predict innovation performance; b. This relationship is mediated by role stress (cognition) and job vigor (affect); c. Innovative self-efficacy negatively moderates the impact of role stress on innovation performance and positively moderates the impact of job vigor on innovation performance; d. Moreover, innovative self-efficacy significantly moderates the mediating effect of role stress and job vigor, and the moderated mediating model is established; (4) Conclusions: Our findings reveal the “black box” of mentoring relationships in the process of influencing the innovation performance of post-90s employees, an area that has received limited research attention. This study further reveals the boundary effect of innovative self-efficacy.

1. Introduction

Facing fierce competition, today, the ability to sustain and thrive has become an ever more critical concern for enterprises. Employee innovation stands as a pivotal factor in propelling organizational innovation, particularly in dynamic and highly competitive environments [1,2]. With the intergenerational transmission of the labor force, scholars are aware of the importance of fostering post-90s employees [3], who have gradually entered the workplace and become a new driving force for organizational development [4]. Most post-90s employees have benefited from an increasingly optimized educational environment and capabilities and have developed a broad mindset, enabling them to thrive in challenging work environments [1,5]. Their inherent creativity brings a wealth of diverse knowledge resources to organizations [6,7]. However, they tend to exhibit higher demands for self-determination and may possess self-centered habits [1,8]. In addition, they might show weaker collective consciousness and lower work enthusiasm, leading to difficulties in making sustained contributions to the organization [9]. Therefore, based on the unique characteristics of post-90s new employees, how to stimulate their innovative potential has become an urgent issue to be addressed.

In response to this challenge, an increasing number of Chinese companies are beginning to experiment with the implementation of mentorship programs as a formal organizational socialization strategy to help ‘post-90s’ employees within the organization [10]. The mentoring system in an organization is highly regarded as an essential tool for human resource management and development [11,12]. Mentoring relationships are supportive and developmental interpersonal exchanges between employees with limited knowledge, experience, and skills (protégés) and those with abundant knowledge, experience, and skills (mentors) [13]. Mentors possess a unique form of social capital, as they have the capability to provide valuable information, career opportunities, and emotional encouragement [14,15].

Previous studies have been conducted on mentoring relationships, revealing their positive effects on various aspects of the protégé’s career development [16,17]. For instance, studies have shown that mentoring relationships are associated with higher levels of job satisfaction [18,19], perceived career success [1,20], affective commitment, and self-esteem [18,21,22]. However, the research on the influence of a mentoring relationship on a protégé’s innovation is insufficient. It is only in recent years that exploration has commenced into the effects of mentor guidance on employees’ innovation and its underlying mechanisms. Only a limited number of studies have examined the impact of mentoring relationships on the protégés’ innovation [23,24,25,26], and these studies are mostly based on a single path of cognition or affect [27,28,29]. For example, mentoring has been found to enhance employees’ innovation capability by stimulating their energy and creating a sense of psychological safety [30,31]. However, behavior is the response that occurs after a complex interaction between cognition and emotion [32]. Thus, the internal mechanisms that explain how mentoring relationships impact employees’ innovation performance could be more comprehensive based on the cognitive-affective dual path.

In addition, most research on mentoring relationships has been conducted in the West, and some scholars have wondered if conclusions about mentoring can be extended to other cultures [33]. Some scholars have indicated that under the context of Chinese Confucian culture and a relationship-oriented society, older individuals perceive assisting younger ones as their responsibility [34], making mentorship readily accessible. In that case, the effect of mentors’ guidance on their protégés may not be guaranteed [35]. In response to scholars’ calls and to test whether mentoring has different impacts in different cultures, it is particularly necessary to explore the effect of mentoring relationships in the Chinese context.

Therefore, this article conducts empirical research to reveal the “black box” of mentoring relationships in the process of influencing the innovation performance of post-90s employees in the Chinese context. Drawing on the Cognitive-Affective Personality System theory (CAPS) and Conservation of Resources theory (COR), the specific approach was as follows: Firstly, we explored whether mentoring relationships had an impact on employees’ innovation performance. Secondly, from the perspective of acquiring and depleting resources, we considered job vigor as a valuable affective resource and role stress as a loss of cognitive resources. By constructing two parallel pathways of cognition and affect, we examined the mechanisms through which role stress and job vigor influenced innovation performance. Finally, we investigated whether mentoring relationships influence role stress and job vigor, which subsequently affect post-90s employees’ innovation performance in varying degrees of innovative self-efficacy. With the increasing application of the mentoring system in Chinese enterprises, the research findings provide theoretical and practical value for organizational innovation management and contribute to deepening managers’ and employees’ understanding of the mentor–protégé interaction process, offering significant insights to inspire innovative performance.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Cognitive-Affective Personality System Theory

The Cognitive-Affective Personality System theory (CAPS), proposed by Mischel and Shoda (1995), provides an explanation for the issue of consistency in human behavior across time and situations [32,36,37,38]. According to CAPS, personality can be understood as a dynamic cognitive-affective processing system. It suggests that the interactions between individuals and their experiences influence their behavior through the complex cognitive-affective units (CAUs) within their personalities [23].

CAPS reveals a series of underlying processes from situation to behavior [39,40]. The final behavior is influenced by both situational factors and the activation of cognitive and affective networks [41]. This provides an effective theoretical explanation for understanding employee behavior in certain specific social contexts and social relationships [32]. Previous research has been conducted on the integration of cognition and emotion, regarding leadership behavior as a crucial organizational contextual variable, and examining its effects on employee advice behavior [42,43] and innovation performance [44]

2.2. Conservation of Resources Theory

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory explains the generation of and coping with stress by focusing on individual resources as the core mechanism [45]. According to this theory, individuals possess limited personal resources, including tangible, identity, personal, and energy resources, and they are motivated to acquire, preserve, and maintain these valuable resources. Regarding resources, existing research has indicated a correlation between individuals’ positive emotions and productive behaviors [46] and the impact of psychological support [47] and relationships [48] on turnover intention, job satisfaction, and performance. Hobfoll [49] suggests that driven by evolution, humans always strive to obtain, protect, and build these resources, viewing resource loss and its risk as threats. When people lose resources, perceive potential losses, or invest resources without receiving expected returns, they experience a sense of stress. Additionally, Hobfoll points out that human stress responses are not just simple stimulus–response processes; individuals engage in proactive stress prevention and coping strategies.

2.3. Mentoring Relationships and Innovation Performance

Previous studies hold three perspectives on an individual’s performance: behavior, outcome, and integration [50]. Oldham and Cummings (1996) [51] defined employees’ innovation performance as the creation of novel products, ideas, or processes that were valuable to the organization, encompassing both behavior and outcome [1]. Following prior studies, we adopted an integration perspective, which has been widely used to investigate employees’ innovation performance.

According to CAPS theory, individuals do not passively or indifferently respond to external situations. Instead, they actively process and react to contextual information, which in turn influences their behavior [32]. Prior to engaging in innovative behavior, employees participate in constructing the meaning of the information present in the workplace [52]. Contextual features within the work environment influence individuals’ personalities and cognitive characteristics [53], thereby influencing their innovative behavior.

Mentoring relationships, as developmental relationships that provide psychosocial support such as sponsorship, protection, exposure, and visibility, can foster a conducive environment for their innovative endeavors [54,55]. These relationships enhance the protégés’ psychological availability and innovation capability [56,57,58], thereby having a positive impact on their innovation performance [56,59]. Moreover, mentors can help protégés acquire the knowledge, skills, and experience necessary for innovation by offering career guidance, especially in the transfer of tacit knowledge [60]. This contributes to improving protégés’ cognitive abilities and confidence in innovation. Additionally, mentors also serve as role models, and protégés can integrate and upgrade their expertise by emulating mentors to improve their abilities to innovate [61,62]. Meanwhile, the process of experiential exchange between mentors and protégés facilitates the emergence of innovative thinking [63,64], which could ultimately improve their innovation performance [65,66]. Therefore, this study proposes that:

H1.

The mentoring relationships of post-90s employees are positively related to their innovation performance in the Chinese context.

2.4. The Cognitive Path: The Mediating Role of Role Stress

Upon entering the workplace, employees often face pressures, including accurate cognition and role orientation [67], which lead to psychological stress and the excessive use of cognitive resources [68]. The cognitive system provides templates for individuals to select and interpret information, which can influence the way they interpret external stimuli. Therefore, this study adopted the CAPS theory to analyze the mediating effect of role stress from the perspective of cognitive resource depletion.

Role stress refers to the pressure that individuals experience when they believe they are unable to meet the expectations of their roles, including role ambiguity, role conflict, and role overload. Unfamiliar working environments require individuals to expend more effort evaluating and executing appropriate coping strategies to minimize the negative effects of stressors. This increased effort can result in excessive depletion of cognitive resources [69] and may also lead to psychological stress associated with role stress [70,71]. Previous studies have indicated that role stress has a negative impact on individual job performance [72]. For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Gilboa et al. found that role ambiguity had the strongest negative correlation with performance compared to other job-related stressors [72]. Another study by Montani confirmed that higher levels of obstacle stressors, such as role ambiguity and role conflict, indirectly affected employee innovation by reducing their emotional organizational commitment [73,74].

From the perspective of resource acquisition and conservation, mentor assistance represents a valuable resource. During the mentoring process, supports provided by mentors, such as career guidance, psychological support, and role modeling, can reduce the level of role stress for protégés through their internal coding process, activating cognitive units. Gelard et al.’s research indicated that friendly relationships with superiors enabled employees to acquire constructive information about work arrangements and execution, leading to a clearer understanding of role expectations and a reduction in role ambiguity and conflict [75]. Thomas and Lankau proposed that the quality of leader–member exchange reduced employees’ perception of role stress. Positive superior–subordinate relationships help employees clarify their job roles and cultivate a more positive work attitude [76]. Consequently, employees who receive guidance from mentors experience low levels of role stress.

According to CAPS theory, the activation of an individual’s cognitive unit triggers a series of chain reactions that lead to corresponding behavioral outcomes. Role stress, being an important cognitive factor, can result in rigid thinking patterns and difficulties in generating innovative ideas when triggered, ultimately negatively impacting an individual’s innovation behavior. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2a.

Role stress will mediate the connection between mentoring relationships and the innovation performance of post-90s employees.

2.5. The Affective Path: The Mediating Role of Job Vigor

Job vigor is a positive emotional experience [77] in which individuals feel energized [78,79]. More precisely, employees with job vigor demonstrate elevated levels of energy, psychological resilience, motivation to make efforts, and determination [80,81]. They do not easily become fatigued, even when facing challenges [82]. It represents a unique positive physical and emotional resource that individuals can transfer to other domains of life [83].

According to the CAPS, affective response is primarily managed by affective units that encompass feelings and emotions. If the individual’s positive emotions are stimulated, they will adopt a positive work attitude, improve the frequency of communication with others, and more easily generate creative ideas [84,85,86]. Research has shown that job vigor can enhance employees’ initiative [87] and encourage them to solve problems creatively [84]. Shirom suggested that job vigor was positively correlated with job performance, thereby providing support for the association between vigor and innovation performance.

From the perspective of resource acquisition and conservation, mentoring relationships will positively affect job vigor. Mentors’ psychological support serves as emotional support that fosters a high level of job vigor in protégés. The more resources employees have, the stronger their job vigor will be. Furthermore, the mentoring relationships facilitate communication and exchange between mentors and protégés, leading to protégés demonstrating more optimistic and proactive attitudes [65] in the workplace. These positive changes contribute to enhancing job vigor among post-90s employees. Previous studies have shown that mentors can bring energy to protégés [88], which can produce a series of positive results, including high-quality work performance [89]. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2b.

Job vigor will mediate the connection between mentoring relationships and the innovation performance of post-90s employees.

2.6. Moderating Role of Innovative Self-Efficacy

The occurrence of any innovative behavior is intricately linked to its specific context. Therefore, exploring the boundary conditions that can influence innovative behavior/ performance is a crucial direction in the study. According to social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is the result of social cognition, as reflected in employees’ comprehensive understanding [90], working engagement [91], and effective self-assessment [92]. Tierney and Farmer (2003) proposed that self-efficacy included beliefs about creative methods in addition to beliefs about achieving innovative outcomes [93]. Drawing from the Conservation of Resource theory, this study further introduced an individual characteristic variable: innovative self-efficacy. Innovative self-efficacy serves a dual purpose: firstly, it moderates the adverse effects of role stress on innovation performance by slowing down resource depletion; secondly, it enhances an individual’s job vigor by promoting resource augmentation. Consequently, innovative self-efficacy plays a moderating role in the second stage of the cognitive-affective pathway.

Innovative self-efficacy pertains to an employee’s strong belief and confidence in their capability to accomplish creative and innovative outcomes [94]. The results of an individual’s self-judgment regarding their capabilities directly influence their subsequent behavioral performance [95]. As an “inner drive” for innovative behavior [94,96,97,98], innovative self-efficacy can motivate employees to implement innovative ideas [99] and proactively deal with challenges, uncertainty, and risks [100,101].

Individuals with different levels of innovative self-efficacy may have different impacts of role stress on innovation performance. When employees possess a high level of creative self-efficacy, it activates a characteristic cognitive pattern and stimulates their innovation beliefs and inner drive. As a result, even in situations where employees perceive significant role stress early in their careers, they maintain the confidence to complete innovative tasks. Consequently, the negative impact of role stress on innovation performance is weakened.

To sum up, individuals with high innovative self-efficacy experience a weakened negative impact of role stress on innovation performance compared to those with low innovative self-efficacy. Consequently, this study puts forward the following hypothesis:

H3a.

Innovative self-efficacy plays a negative moderating role in the relationship between role stress and innovation performance.

The CAPS theory emphasizes the interaction between an individual’s cognition and affect units, which in turn influences their behavior. Innovation is influenced by both individuals’ creative self-efficacy (cognitive) and job vigor (affective). Different levels of innovative self-efficacy may lead to varying impacts of job vigor on innovation performance. Specifically, employees with high innovative self-efficacy exhibit greater confidence in their innovation abilities and tend to positively assess their available resources. They display a more optimistic work attitude and engage in active thinking, which further promotes their creative thinking and exploratory activities [64].

In conclusion, individuals with high innovative self-efficacy exhibit a stronger positive effect of job vigor on innovative performance compared to those with low innovative self-efficacy. We anticipate that the impact of job vigor on innovation among new employees will vary depending on their level of innovative self-efficacy. Hence, this study proposes:

H3b.

Innovative self-efficacy positively moderates the relationship between job vigor and innovation performance.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes a moderated mediation model in which innovative self-efficacy moderates the mediation effects of role stress and job vigor between mentoring relationships and employee innovation performance. On the cognitive path, when individuals have high innovative self-efficacy, supports offered by mentors reduce role stress by minimizing the negative impact of stressors such as anxiety, tension, and fatigue, thus weakening their effects on individual innovation performance. Consequently, individuals’ high innovative self-efficacy weakens the mediating effect of role stress between mentoring relationships and innovation performance. On the affective path, when individuals have high innovative self-efficacy, mentors’ guidance enhances their job vigor by making them feel more energized, passionate, and confident, which in turn enhances their innovation performance. As a result, individuals’ high innovative self-efficacy strengthens the mediating effect of job vigor between mentoring relationships and innovation performance. Conversely, when individuals have low innovative self-efficacy, the effect of mentor support on enhancing their job vigor is inhibited, reducing their motivation to innovate, and making it difficult for job vigor to enhance their innovation performance.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, we further anticipate that innovative self-efficacy influences the strength of the indirect effects of role stress and job vigor. As a result, this study puts forward the following hypotheses:

H4a.

Innovative self-efficacy moderates the mediation effect of mentoring relationships on protégés’ innovation performance through role stress.

H4b.

Innovative self-efficacy moderates the mediation effect of mentoring relationships on protégés’ innovation performance through job vigor.

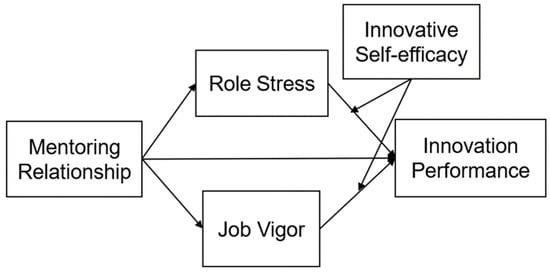

Drawing from the above analysis, this study formulates a theoretical model comprising five variables: mentoring relationships, role stress, job vigor, innovative self-efficacy, and innovation performance, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Description

Firstly, employee data were collected through a questionnaire survey targeting post-90s employees based on their age. To ensure the quality of the survey, all participants voluntarily participated, and reverse-scored items were included to control response bias. Participants completed the questionnaire items using mobile phones or computers, responding to measures related to mentoring relationships, innovative self-efficacy, innovation performance, job vigor, and role stress. Additionally, this study collected demographic variables, including gender, education level, years of work experience, and years of tenure in the current organization, to examine their potential impact on the research findings.

After collection and screening, among the total questionnaires distributed, 518 valid responses were received, yielding a response rate of 90.97%. Among the respondents, 96.1% had working experience within the 1–5 year range. The highest education level was concentrated in undergraduate and master’s degrees or above, accounting for 65.9% and 24.5%, respectively. Furthermore, 74.7% of the participants had working experience within the 1–3 year range in their current enterprise or organization, with the majority (77.3%) holding ordinary employee positions.

3.2. Measures

To enhance the reliability and validity of the measurements, established scales from both the domestic and international literature were carefully chosen for this study.

The mentoring relationships scale, adapted from Scandura and Ragins (1999) [102], comprised 15 items. It included psychological and social support items such as “I trust my mentor” (5 items), career guidance items such as “My mentor is interested in my career” (6 items), and role modeling items such as “I consider my mentor a role model and someone to emulate” (4 items). Cronbach’s α was 0.855.

The innovation performance scale, developed by Han Yi, comprised 8 items. This study utilized 8 items, including 2 items for innovation willingness, such as “I am willing to propose new ideas to improve various environments”, 3 items for innovation action, such as “I will continuously learn and enhance my skills for better work”, and 3 items for innovation outcome, such as “I will come up with novel solutions for some difficult problems through learning.” Cronbach’s α was 0.901.

The role stress scale, developed by Peterson [103], comprised 13 items. This scale assessed various aspects of role stress, including items such as “I often face situations where goals conflict with each other.” Cronbach’s α was 0.818.

The measurement of job vigor used in this study employed a scale developed by Yanming He [104]. This scale was specifically designed for the Chinese organizational context and comprised four dimensions: learning, initiative, responsibility, and energy. It included a total of 16 items. Cronbach’s α was 0.913.

The measurement of innovative self-efficacy used in this study adopted a locally adapted scale revised by Gu Yuandong and Peng Jisheng (2011) [105]. This scale, consisting of 8 items, is considered representative in assessing innovative self-efficacy. Cronbach’s α was 0.9.

Control variables. This study included several demographic variables as control variables, such as age, gender, and education level.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations (SD), and correlation coefficients among all variables. The results show significant positive correlations between mentoring relationships and job vigor (r = 0.611, p < 0.01), as well as significant negative correlations between mentoring relationships and role stress (r = −0.414, p < 0.01). Additionally, significant positive correlations were found between role stress (r = −0.533, p < 0.01), job vigor (r = 0.561, p < 0.01), innovative self-efficacy (r = 0.544, p < 0.01), and innovation performance. Moreover, innovative self-efficacy showed significant correlations with role stress (r = −0.373, p < 0.01) and job vigor (r = 0.537, p < 0.01). These findings offered initial support for our hypotheses.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4.2. Common-Method Bias Test

To control for common-method bias, this study implemented measures such as anonymous data collection and partial reverse scoring. Additionally, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted on the collected data to examine the presence of common-method bias. The results revealed that the unrotated first principal component accounted for only 27.284% of the total variance, which was below the critical threshold of 50%. This result suggests that the majority of the variance in the data cannot be attributed to a single factor. Thus, the influence of method bias on this study was not substantial [106].

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We used AMOS to conduct CFA on both the baseline model and other competing models. The results are presented in Table 2. The baseline model includes five variables: mentoring relationships, innovative self-efficacy, job vigor, role stress, and innovation performance. The results indicate that the baseline model fits well (χ2/df = 2.168 < 3, CFI = 0.861 > 0.8, TLI = 0.855 > 0.8, RMSEA = 0.048 < 0.08) and performs better than the competing models across various indicators. This suggests that the core variables of this study demonstrate good discriminant validity, thereby supporting further research analysis.

Table 2.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis.

4.4. Tests of Hypotheses

4.4.1. The Test of Mediating Effects

This study utilized SPSS 26.0 software to conduct hierarchical regression analyses and hypothesis testing, as presented in Table 3. The results indicated that the mentoring relationships had a significant positive impact on protégés’ innovation performance (M6, β = 0.599, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

Results of regression analysis.

In terms of the mediating role of role stress, from M2, it was observed that the mentoring relationships were significantly negatively correlated with role stress (M2, β = −0.404, p < 0.001). Additionally, M8 revealed that, after including role stress, it had a significant negative effect on innovation performance (M8, β = −0.351, p < 0.001). Moreover, the influence of mentoring relationships (M8, β = 0.457, p < 0.001) on innovation performance decreased compared to M6, indicating that role stress partially mediated the relationship between mentoring relationships and innovation performance, thus Hypothesis 2a was supported.

In terms of the mediating role of job vigor, according to M4, the mentoring relationships had a significant positive impact on job vigor (M4, β = 0.604, p < 0.001). When incorporating job vigor, it demonstrated a significant positive effect on innovation performance (M10, β = 0.31, p < 0.001), and the influence of mentoring relationships (M10, β = 0.412, p < 0.001) on innovation performance decreased compared to M6. These findings indicated that job vigor partially mediates the relationship between mentoring relationships and innovation performance, thus supporting Hypothesis 2b.

The SPSS Process macro was used for bootstrap testing to confirm the mediating effects of role stress and job vigor. The random sampling was set to 5000 iterations with a 95% confidence interval, and the results are presented in Table 4. The mediating impact of role stress on the second part of the model was 0.188, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.128, 0.253], which did not include 0. Similarly, the mediating impact of job vigor on the second part of the model was 0.234, with a confidence interval of [0.152, 0.322], which did not include 0. The difference between the two paths was −0.046 and the boot 95% CI was [−0.155, 0.061], which included 0. Therefore, the difference between the two paths is not significant. Hypothesis 2a and 2b are further supported, indicating that the impact of mentoring relationships on protégés’ innovation performance is realized through both cognitive and affective paths.

Table 4.

The results for mediating effect.

4.4.2. The Test of Moderating Effects

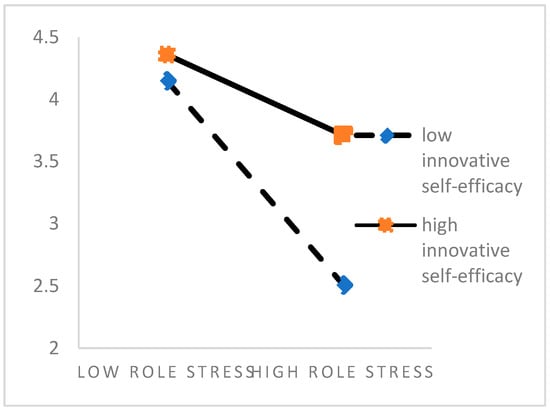

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis carried out to reveal the relationship between role stress/job vigor and innovation performance are presented in Table 3. Role stress had a negative impact on innovation performance (M7, β = −0.534, p < 0.001). After including the interaction terms of role stress and innovative self-efficacy in the model (M12, β = 0.14, p < 0.001), the regression equation became significant, and the coefficient of the interaction term was significantly positive. As the regression coefficient of role pressure on innovation performance was negative, it indicated that innovative self-efficacy weakens the impact of role stress on innovation performance. Hypothesis 3a was supported.

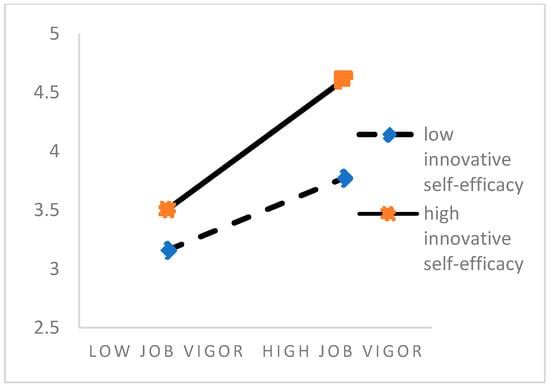

As shown in Table 3, it was found that job vigor had a significant positive impact on innovation performance (M9, β = 0.557, p < 0.001). The interaction of job vigor and innovative self-efficacy was significant (M14, β = 0.09, p < 0.05). This indicated that innovative self-efficacy enhanced the impact of job vigor on innovation performance. In other words, innovative self-efficacy had a significant facilitating effect on the relationship between job vigor and innovation performance, Hypothesis 4b, Innovative self-efficacy moderates the mediation effect of mentoring relationships on protégés’ innovation performance through job vigor, was supported.

In addition, following Aiken and West [107], we conducted a simple slope analysis to analyze the moderating effect of innovative self-efficacy at different levels. As shown in Figure 2, the negative effect of role stress on innovation performance was weakened under high levels of innovative self-efficacy (simple slope β = −0.396, p < 0.001). Therefore, role stress had a stronger negative effect on innovation performance when employees’ innovative self-efficacy was at a lower level (simple slope β = −0.754, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

The moderating effect on the relationship between role stress and innovation performance.

As shown in Figure 3, the positive effect of job vigor on innovation performance was strengthened when employees’ innovative self-efficacy was at a higher level (simple slope β = 0.517, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, job vigor had a weaker positive effect when employees’ innovative self-efficacy was at a lower level (simple slope β = 0.341, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

The moderating effect on the relationship between job vigor and innovation performance.

4.4.3. The Test of Moderated Mediating Effects

To further investigate the parallel mediating effect of role stress and job vigor between mentoring relationships and innovation performance, the SPSS plugin Process Macro was used to conduct a Bootstrap test. The random sampling was set to 5000 iterations, and the confidence interval was set to 95%. Edwards and Lambert (2007) [108] emphasized that when examining the mediated moderation effect, where both mediation and moderation affects occur simultaneously, the moderated mediation model should be analyzed as a whole. Therefore, this study utilized the Process Macro (Model 14) developed by Hayes (2013) [109] to test the indirect effects of role stress and job vigor on innovation performance under different levels of innovative self-efficacy. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The moderated mediation effect test.

The results showed that when innovative self-efficacy was high, the indirect effect of role stress was significant. The effect size was 0.066 and the boot 95% CI was [0.026, 0.106], which did not include 0. When innovative self-efficacy was low, the indirect effect of role stress was also significant. The effect size was 0.332 and the boot 95% CI was [0.235, 0.433], which did not include 0. The difference between high and low levels was significant, and the 95% confidence interval did not include 0. Furthermore, the index for the moderated mediation was calculated based on the PROCESS analysis to further test the existence of the moderated mediation. The index for the moderating effect of innovative self-efficacy on the relationship between mentoring relationships and innovation performance through reducing role stress was −0.185 and the boot 95% CI was [−0.246, −0.125], which does not include 0. This supported hypothesis H4a. Therefore, the innovative self-efficacy of the protégés negatively moderated the mediating effect of role stress between the mentoring relationships and innovation performance.

The results showed that when the protégés’ level of innovative self-efficacy was higher than one standard deviation, the indirect effect of job vigor was significant. The effect size was 0.324 and the boot 95% CI was [0.205, 0.460], which did not include 0. When the level of innovative self-efficacy was lower than one standard deviation, the indirect effect of job vigor was significantly positive. The effect size was 0.211 and the boot 95% CI was [0.120, 0.297]. The difference between high and low levels was significant, and the 95% confidence interval did not include 0. Furthermore, the index for the moderated mediation was investigated based on the PROCESS analysis to test the moderating effect of innovative self-efficacy on the affective path. The index was 0.079 and the boot 95% CI was [0.002, 0.173], which did not include 0. This supported hypothesis H4b. Therefore, the innovative self-efficacy of the protégés positively moderated the mediating effect of job vigor

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

To gain deeper insight into how mentoring relationships among new employees promote their innovation performance, this study goes beyond the current research trends by not only examining the cognitive-affective dual path as a pivotal mechanism connecting mentoring relationships to innovation performance but also delving into the influence of innovative self-efficacy on the innovation performance of post-90s employees.

Based on the CAPS theory, a dual-path model incorporating cognitive and affective paths was constructed, and the boundary conditions affecting the second stage of the affective path and the cognitive path were examined separately. The results of the study are as follows: (1) Mentoring relationships have a significant positive impact on the innovative performance of post-90s employees. Enterprises could make full use of mentoring systems in innovation management. (2) Role stress and job vigor serve as partial mediators between mentoring relationships and the innovation performance of post-90s employees. The influence of mentoring relationships on innovation performance is realized through the cognitive path involving role stress and the affective path involving job vigor. Managers should pay attention to both the cognition and affect of post-90s employees to stimulate their innovative potential. (3) Innovative self-efficacy plays a moderating role in the relationship between role stress and innovation performance. Higher levels of innovative self-efficacy weaken the negative impact of role stress. Specifically, individuals with high innovative self-efficacy experience a weakened negative impact of role stress on innovation performance compared to those with low innovative self-efficacy. (4) Innovative self-efficacy positively moderates the relationship between job vigor and innovation performance. Higher levels of innovative self-efficacy strengthen the positive impact of job vigor. Specifically, individuals with high innovative self-efficacy exhibit a stronger positive effect of job vigor on innovative performance compared to those with low innovative self-efficacy. Individuals with higher levels of innovative self-efficacy may have more potential to innovate.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Firstly, we provide valuable insight into the correlation between mentoring relationships and innovation performance, an area that has received limited research attention. In recent years, mentoring relationships in academic research have gained significant attention, with most studies focusing on outcomes of mentoring such as job satisfaction and career success [110]. However, there is a scarcity of research specifically examining the relationship between mentoring relationships and protégés’ innovation performance. The intrinsic mechanisms between mentoring relationships and innovation performance were further explored, expanding the understanding of antecedent mechanisms related to innovation performance and responding to the call by Han et al. (2013) [88] to extend research on the mechanisms through which mentoring relationships influence protégés.

Secondly, this study found that role stress and job vigor among post-90s employees partially mediated the relationship between mentoring and innovation performance. These findings help clarify the actual pathways through which employees’ innovative performance was influenced, providing an integrative explanation of employees’ innovation performance. Based on the perspectives of the CAPS, this study explored the underlying mechanisms of mentoring relationships on the innovation performance of post-90s new employees by constructing a dual-path model that incorporates cognitive and affective paths. By combining the integrated perspectives of resource gain and loss, a dual-mediation model of affect and cognition was constructed, introducing role stress and job vigor as the mediating factors, respectively.

In the field of mentoring research, most scholars adopted theories such as social learning theory [111], social cognitive theory [28], or social network theory [29]. These studies almost all examined the influence of mentoring relationships on protégés’ career development and job performance [112]. Previous research on innovation performance has been relatively limited in terms of the perspectives, such as social exchange theory [113], social cognitive theory [114], or social learning theory [115], commonly used. By utilizing the CAPS theory, our findings revealed the “black box” of mentoring relationships in the process of influencing the innovation performance of post-90s employees. This study not only provided new perspectives for understanding the underlying mechanisms behind the influence of mentoring relationships but also provided support for the applicability of the CAPS theory in explaining the mechanisms through which mentors influence protégés.

Thirdly, this study further revealed the boundary effect of innovative self-efficacy, adding to the existing literature by expanding the understanding of contextual factors that contributed to the effectiveness of mentoring relationships. Our findings diverged from prior mentoring research [116], which highlighted the importance of contextual factors in mentoring effectiveness. Based on social cognitive theory, the moderating role of innovation self-efficacy was considered. We further explored the moderating effect of innovative self-efficacy on innovation performance, which presented a fresh theoretical viewpoint for investigating the contextual factors that influenced the relationship between an individual’s cognitive units (role stress) and affective units (job vigor) on innovation performance but also enriched the theoretical application of social cognition theory.

5.3. Practical Implications

This paper presents three managerial recommendations.

Firstly, we recommend that leaders and policymakers establish a talent development mechanism based on mentor–protégé relationships to effectively manage internal human resources within organizations. Our findings suggest that mentoring not only directly affects the innovation performance of post-90s employees but also enhances it through two paths: relieving role stress and stimulating job vigor. Therefore, managers should prioritize implementing a mentoring system that allows new employees to receive guidance and assistance from mentors as soon as they enter the organization.

Secondly, managers should focus on the role cognition and affective attitudes of new employees, such as role stress and job vigor. Encouraging mentors to fully utilize the three functions of career development guidance, social psychological support, and role modeling. Additionally, mentors should also prioritize communication and exchange with new employees who might be influenced by role stress, providing them with necessary physiological, emotional, and cognitive resources. This will help to improve new employees’ work enthusiasm, stimulate motivation, reduce role stress, and ultimately promote post-90s employees’ innovative behavior and performance.

Thirdly, developing and selecting employees with high creative self-efficacy is critical for organizational innovation and development. Managers should not only pay attention to new employees’ occupational skills, stress levels, and vitality but also take into account their sense of innovation efficacy. They can formulate policies and provide resources to help employees increase their confidence in engaging in innovative activities, thereby enhancing their innovation self-efficacy. Moreover, organizations can also carry out psychological assessments at the stage of recruitment, giving priority to employees with higher work motivation and innovative self-efficacy.

5.4. Limitations

Despite the confirmation of the mechanism of mentoring relationships and innovation performance, there are still some limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the use of cross-sectional data limits the ability to examine the dynamic developmental process of mentoring relationships and innovation performance. Future researchers could design longitudinal research, collecting data at multiple time points, to better understand how new employees and organizations can dynamically benefit from mentoring relationships. Additionally, mentor–protégé paired data could be used to reduce systematic bias. Secondly, this study focuses on individual-level factors and does not consider organizational factors that may influence the relationship between mentoring relationships and innovation performance. Future research could adopt a multi-level approach, considering factors at both the individual and organizational levels, such as the organizational innovation climate, to understand the mechanisms underlying the mentoring–innovation performance relationship. Thirdly, this study does not consider the potential impact of industry and regional characteristics on the surveyed individuals. It is possible that industry differences could impact creativity and innovation. Future studies could conduct industry-specific investigations to explore these potential effects and enhance the generalizability of the findings. In addition, mentors in our sample are limited to organizations. In subsequent studies, researchers have the opportunity to extend the definition of mentors, as advocated by van Emmerik et al. (2004) [117], to encompass mentors not limited to the organizational context but also individuals from families and communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, review, and supervision, M.L.; data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, Z.J.; writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing, Z.J. methodology and review, G.L., J.Y. and Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project, grant number 72002016. the Project of Beijing Social Science Fund, grant number 22GLC043; The Cultivation for Young Top- notch Talents of Beijing Municipal Institutions, grant number BPHR202203241; the Shandong Provincial Youth Innovation Science and Technology Support Program, grant number 2021RW031.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Economics and Management, Beijing Information Science and Technology University (136 and 2023.3.1).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data cannot be publicly released due to the inclusion of personal information. However, the data can be shared under reasonable circumstances if there are valid needs.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all the participants for their valuable cooperation in data collection for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wang, T.; Chen, C.; Song, Y. The “double-edged sword” effect of challenging stressors on employees’ innovative behavior. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2019, 5, 90–100+141. [Google Scholar]

- Nasifoglu Elidemir, S.; Ozturen, A.; Bayighomog, S.W. Innovative Behaviors, employee creativity, and sustainable competitive advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.; Bondarouk, T.; Nijenhuis, K. Innovative work behavior in knowledge-intensive public sector organizations: The case of supervisors in the Netherlands fire services. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, Y.; Tu, Y. The structure, measurement, and impact on performance of the work values of the new generation of employees. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. Management Millennialism: Designing the New Generation of Employee. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Thundiyil, T.G. The comparative effects of supervisor helping motives on newcomer adjustment and socialization outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Li, C. The mechanism of the effect of moral leadership and proactive personality on new employees’ job engagement from an interactive perspective. Sci. Sci. Manag. 2018, 156–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, S.; Qin, W. Research on the expectation gap and turnover intention of new generation employees based on the cross-level moderated mediation model. J. Manag. 2021, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Y. Research on intergenerational differences of Chinese employees based on achievement motivation data over 20 years. J. Manag. 2019, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Yang, X.; Yan, F.; Liang, Z.; Wan, L. The application of the 1+n mentorship system in career planning courses for vocational nursing students. Med. Educ. Mod. Nurs. 2023, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małgorzata, B.; Roland, Z. Key effects of mentoring processes—Multi-tool comparative analysis of the career paths of mentored employees with non-mentored employees. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeh, J.H. Impact of participative and authoritarian leadership on employee creativity: Organizational citizenship behavior as a mediator. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2023, 26, 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kram, K.E.; Isabella, L.A. Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, S. The mechanism of the influence of guiding relationship on apprentices’ proactive behavior: The role of job prosperity and learning goal orientation. Forecasting 2019, 38, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, S.M.; Yu, M.V.B.; Johnson, H.E.; Futch Ehrlich, V.; Deutsch, N.L. “It’s going to help me in life”: Forms, sources, and functions of social support for youth in natural mentoring relationships. J. Community Psychol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djiovanis, S.G. Effectiveness of formal mentoring on novice nurse retention: A comprehensive literature review. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2022, 39, E66–E69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D. The Relationship between Guidance Relationship and Innovative Behavior: The Role of Job Embeddedness and Self-Leadership; South China University of Technology: Guangzhou, China, 2018; Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201901&filename=1019825782.nh (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Mohite, D.M.M. Research on Employees Job Satisfaction Factors, Levels of Job Satisfaction and ‘Relationship’ in Different Group. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2021, 5, 415–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jyoti, J.; Sharma, P. Exploring the role of mentoring structure and culture between mentoring functions and job satisfaction: A study of indian call centre employees. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2015, 19, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Reio, T.G. Career benefits associated with mentoring for mentors: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Xiao, Y. Social Network Structure as a Moderator of the Relationship between Psychological Capital and Job Satisfaction: Evidence from China. Complexity 2021, 2021, 2550944. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Gong, Z.; Liao, G. How relationship-building behavior induces new employees’ career success: Effects of mentor tie strength and network density. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2022, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Luo, J. How does dual leadership inspire innovative behavior in new employees? A model based on cognitive-affective perspective in the Chinese context. Sci. Sci. Manag. ST 2020, 41, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Guan, J.; Zhong, J.; Zhao, L. Study on the relationship between dual leadership and team innovation performance based on the mediating effect of dual team behavior. J. Manag. 2017, 14, 814–822. [Google Scholar]

- Rosing, K.; Frese, M.; Bausch, A. Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Robinson, A.J.; Rosing, K. Ambidextrous leadership and employees’ self-reported innovative performance: The role of exploration and exploitation behaviors. J. Creat. Behav. 2016, 50, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.-Y.; Chow, I.H.S. The impact of supervisory mentoring on personal learning and career outcomes: The dual moderating effect of self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 78, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, M.C.; Dobrow, S.R.; Chandler, D.E. Never quite good enough: The paradox of sticky developmental relationships for elite university graduates. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, R.D.; Shen, Y.; Livne-Tarandach, R. Becoming extraordinary: The content and structure of the developmental networks of major league baseball hall of famers. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 15–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Fengzhan, X.; Ming, G. Research on the influence of mentorship on apprentices’ innovative behavior: Based on the perspective of energy. Technol. Econ. 2019, 24–31+49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Han, Y. The influence of mentorship on apprentices’ work vitality and innovation performance in enterprises. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2018, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragins, B.R.; Kram, K.E.; Roosevelt, E. The Roots and Meaning of Mentoring. In Handbook of Mentoring at Work Theory; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. The Ethic of Conviction and Women’s Participation of Elderly Care in Rural Families—An Analysis Based on the Data from Field Research Carried out in a Rural Area Named Wentsing of China. 1 September 2023. Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=878dd94e097f55772c84ec650f820065&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Kim, M.; Seo, S.W. The effect of mentor’s emotional intelligence on psychological similarity and mentoring effectiveness: Focused on airline staff. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. Reconciling processing dynamics and personality dispositions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 229–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W. Toward an integrative science of the person. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoda, Y. Personality as a dynamical system: Emergence of stability and distinctiveness from intra and interpersonal interactions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 6, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoda, Y.; Wilson, N.L.; Chen, J.; Gilmore, A.K.; Smith, R.E. Cognitive-affective processing system analysis of intra-individual dynamics in collaborative therapeutic assessment: Translating basic theory and research into clinical applications. J. Personal. 2013, 81, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qiao, Y. The interaction between cognitive and emotional information in daily consumption decision-making of college students. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Denton, R.; Ayduk, O.N.; Shoda, Y.; Mischel, W. Cognitive-affective processing system analysis of reactions to the o. J. Simpson criminal trial verdict. J. Soc. Issues 1997, 53, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y. Research on the Relationship between Rewards and Innovation Performance from the Perspective of Cognitive Assessment: The Moderating Role of Emotional States and Cognitive Resources. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Behar-Horenstein, K. Efficacy of a mentor academy program: A case study. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2019, 27, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Y. Research on the Relationship between Inclusive Leadership and Advice Behavior from the Perspective of Cognitive-Emotional Integration. Manag. Rev. 2018, 15, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.; Cadet-Laborde, F.; Weisfeld-Spolter, S.; Yurova, Y.; Tworoger, L. Positive affect as a resource and the mediating role of mindfulness on employees during times of disruption. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2023, 37, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Research on the Influence of Entrepreneurial Spiritual Capital on Independent Innovation Behavior: Cognitive Reappraisal and Positive Emotions as Chain Mediators. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.H.; McDonald, B.; Park, J. Person–Organization Fit and Turnover Intention: Exploring the Mediating Role of Employee Followership and Job Satisfaction Through Conservation of Resources Theory. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2018, 38, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Lilly, R.S. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. J. Community Psychol. 1993, 21, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bian, R.; Wang, L.; Che, H.; Lin, X. The relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 20, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Cummings, A. Employee Creativity: Personal and Contextual Factors at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazin, R.; Glynn, M.A.; Kazanjian, R.K. Multilevel theorizing about creativity in organizations: A sensemaking perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, R.W.; Sawyer, J.E.; Griffin, R.W. Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Ma, E.; Li, A. Driving frontline employees performance through mentorship, training, and interpersonal helping: The case of upscale hotels in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen Tammy, D.; Eby Lillian, T.; Poteet Mark, L.; Lentz, L.; Lima, L. Career benefits associated with mentoring for protégeé: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, S. The influence mechanism of master-apprentice system on apprentices’ innovation performance: The role of psychological ownership and proactive personality. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Wen, P.; Chen, Z.; Liao, S.; Shu, X. Formal mentoring support and protégé creativity: A self-regulatory perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 24, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, R.; Chen, S. The influence of mentor-apprentice relationship on the peripheral performance of apprentices: The mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of person-organization fit. Forecasting 2017, 36, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. A review, critique and prospects of enterprise mentorship research. Natl. Circ. Econ. 2021, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J. The influence of mentorship on knowledge transfer of returnees: A moderated mediation model. Forecasting 2018, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Huichi, Q. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Dual Leadership on the Constructive Deviant Behavior of the New Generation of Employees—The Chain Mediating Effect of Promoting Regulatory Focus and Role Width Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 775580. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M.B.; Taylor, E.Z. Developmental mentoring, affective organizational commitment, and knowledge sharing in public accounting firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Zeng, L. Organizational learning and organizational performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 29, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Yu, G. How mentors guide apprentices to foster innovation: A study of the dual pathway mechanism based on cognition and emotion. Econ. Manag. 2021, 43, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Wayne, S.J. Is being a good learner enough? An examination of the interplay between learning goal orientation and impression management tactics on creativity. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 68, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uen, J.F.; Chang, H.C.; McConville, D.; Tsai, S.C. Supervisory mentoring and newcomer innovation performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Dong, X. Psychological conflicts and suggestions of newly enrolled preschool teachers in the process of role transformation. J. Jining Norm. Univ. 2018, 40, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, N.; Hu, Y.; Xu, L. Research on role pressure in organizations: Integrated research framework and future research directions. Soft Sci. 2014, 28, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wei, X.; Cheng, D. The impact of workplace negative gossip on the behavior of gossiped employees: A meta-analysis based on the cognitive-emotional personality system theory. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 2681–2695. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, T.; Weibler, J. What it takes and costs to be an ambidextrous manager. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, U.; Ramay, M.I. Impact of stress on employee’s job performance a study on banking sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2010, 2, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa, S.; Shirom, A.; Fried, Y.; Cooper, C. A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 227–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, F.; Courcy, F.; Vandenberghe, C. Innovating under stress: The role of commitment and leader-member exchange. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. The influence mechanism of work-family conflict on innovative behavior of knowledge workers. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gelard, P.; Rezaie, N. Contextual factors and the creativity of employees: The mediating effects of role stress and intrinsic motivation on economy and finance organization in tehran. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2014, 4, 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.H.; Lankau, M.J. Preventing burnout: The effects of LMX and mentoring on socialization, role stress, and burnout. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Z. The concept, function, and significance of positive emotion. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 15, 810–815. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Chen, X. Vitality in the workplace: Theoretical foundation, concept, and theoretical model. Luojia Manag. Rev. 2014, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. How are changes in exposure to job demands and job resources related to burnout and engagement? A longitudinal study among Chinese nurses and police officers. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2017, 33, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.F.; Spreitzer, G.; Fritz, C. Too much of a good thing: Curvilinear effect of positive affect on proactive behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Bernstein, J.H.; Brown, K.W. Weekends, work, and well-being: Psychological need satisfactions and day of the week effects on mood, vitality, and physical symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 29, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M.; Etzion, D.; Chen, S. Crossover of positive experiences from business travelers to their spouses. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Carmeli, A. Alive and creating: The mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative work involvement. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A. High-quality relationships, vitality, and job performance. In Research on Emotion in Organizations; Ashkanasy, N., Zerbe, W.J., Härtel, C.E.J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pillemer, J. Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2012, 46, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyamin, G.; Brender-Ilan, Y. Leader’s language and employee proactivity: Enhancing psychological meaningfulness and vitality. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 36, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, X.; Yang, B. Structure, mechanism, and effects of mentorship relationships. Manag. Rev. 2013, 25, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, J.; Wang, K.; Han, Y.; Li, Z. The influence of master’s face needs on apprentice’s job dedication: The role of mentoring relationship and emotional intelligence. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2017, 34, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.S.; Wan, C.J.; Ko, S. Interactivity, active collaborative learning, and learning performance: The moderating role of perceived fun by using personal response systems. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wen, T.; Wang, J.; Gao, H. The impact of spiritual leadership on employee’s work engagement—A study based on the mediating effect of goal self-concordance and self-efficacy. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2022, 24, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Arshad, M.; Saleem, S.; Farooq, O. The impact of perceived supervisor support on employees’ turnover intention and task performance: Mediation of self-efficacy. J. Manag. Dev. 2019, 8, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Tierney, P.; Kung-Mcintyre, K. Employee creativity in taiwan: An application of role identity theory. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Guo, P.; Bo, L. The influence of organizational innovation support on the innovation behavior of scientific researchers—Based on the chain intermediary effect of innovation self-efficacy and knowledge sharing. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 41, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. The influence of creative process engagement on employee creative performance and overall job performance: A curvilinear assessment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y. The influence of social capital on primary school teachers’ creative teaching behavior: Mediating effects of knowledge sharing and creative teaching self-efficacy. Think. Ski. Creat. 2023, 47, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, L.; Shi, B. Achievement goals and creativity: The mediating role of creative self-efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 40, 1249–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, M.; Guo, H.; Fan, W.; Lai, L. The influence of transformational tutor style on postgraduate students’ innovative behavior: The mediating role of creative self-efficacy. Int. J. Digit. Multimed. Broadcast. 2023, 2023, 9775338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Suntrayuth, S.; Sun, X.; Su, J. Positive verbal rewards, creative self-efficacy, and creative behavior: A perspective of cognitive appraisal theory. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, T. The influence of platform leadership on innovation performance of knowledge workers: From the perspective of organizational resilience and innovation self-efficacy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 18, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragins, B.R.; Scandura, T.A. Burden or blessing? Expected costs and benefits of being a mentor. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.R. Examining the Role of Agitation and Aggression in Perceived Caregiver Burden. 1995. Available online: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1360&context=jwprc (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- He, Y. Empirical Research on Work Vitality Content Structure and Organizational Influencing Factors. Guangdong University of Technology. 2015. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201502&filename=1015311911.nh (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Gu, Y.; Peng, J. The affect mechanism of creative self-efficacy on employees’creative behavior. Sci. Res. Manag. 2011, 32, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D.; Wen, Z. Testing common method bias: Issues and recommendations. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New Yourk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S.E. The role of mentoring support and self-management strategies on reported career outcomes. J. Career Dev. 2001, 27, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. The impact of error management culture on innovative proactive behavior of new generation employees: A three-way interaction moderation model. Sci. Technol. Prog. Countermeas. 2023, 1–10. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/42.1224.G3.20230604.0141.006.html (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Allen Tammy, D.; Eby Lillian, T.; Chao Georgia, T.; Bauer Talya, N. Taking stock of two relational aspects of organizational life: Tracing the history and shaping the future of socialization and mentoring research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, K.T.; Nguyen, P.V.; Pham, N.H.T.; Le, X.A. The roles of transformational leadership, innovation climate, creative self-efficacy, and knowledge sharing in fostering employee creativity in the public sector in Vietnam. Int. J. Bus. Contin. Risk Manag. 2021, 11, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. Ethical leadership and its impact on service innovative behavior: The role of LMX and job autonomy. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Min, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, D. The mechanism and boundary of the impact of family adaptability on employee innovation behavior. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 522–530. [Google Scholar]

- Aikens, M.L.; Robertson, M.M.; Sadselia, S.; Watkins, K.; Evans, M.; Runyon, C.R.; Eby, L.T.; Dolan, E.L. Race and gender differences in undergraduate research mentoring structures and research outcomes. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, ar34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetty van Emmerik, I.J. The more you can get the better—Mentoring constellations and intrinsic career success. Career Dev. Int. J. Exec. Consult. Acad. 2004, 9, 578–594. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).