Golf Club Management Challenges towards Sustainability: Opportunities and Innovations during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Qualitative Methods

2.3. Data Analysis

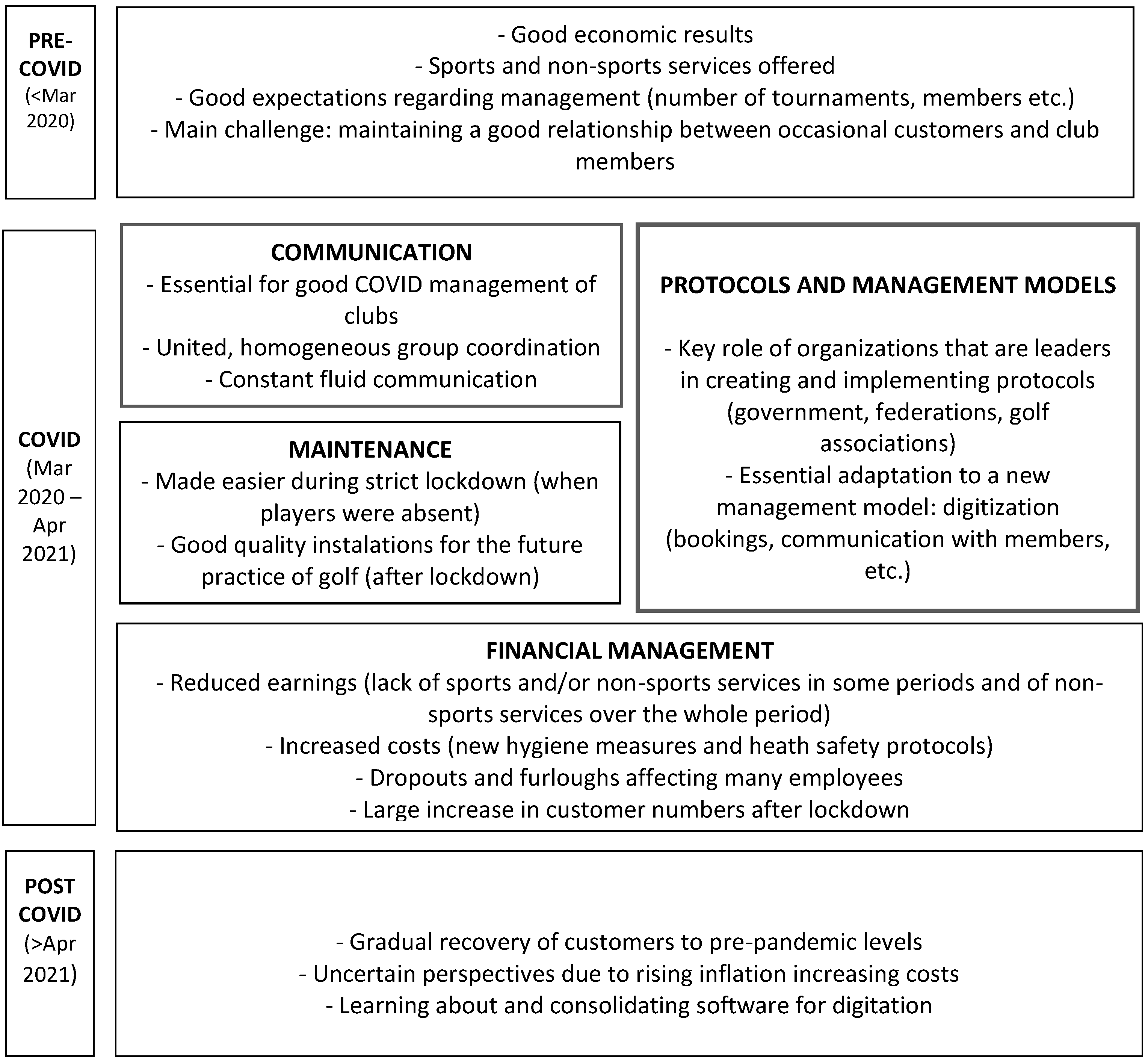

- Management pre-pandemic: items regarding management before March 2020.

- Management during lockdown and restrictions: items regarding management during the period of lockdown and restrictions from March 2020 to March 2022.

- Management post-pandemic: items regarding management after lifting all restrictions from March 2022 until the present (December 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Management Pre-Pandemic

“We had almost doubled our members from 2016 to 2020”. (Carlos #1)

“At the competition level we had hosted a professional championship, we had been growing in the sports setting, organizing competitions of ever higher level, and in the more social setting, we indeed had great tournaments… 2020 was a year in which we still had many scheduled sponsorships, and, in the club, there was an air of optimism”. (Pedro #2)

“As a major problem was the issue regarding the relationship between customers and members (…) although it has been explained a thousand times that occasional customers are needed to complete earnings as with 500 members paying their subscription it is not enough to maintain a club of these characteristics. This issue of friction between members and other customers is difficult to resolve”. (Roberto #3)

3.2. Management during Lockdown and Restrictions

3.2.1. Financial Management

“We had positive EBITDA, and the government’s furlough scheme also helped because staff wages are the highest fixed cost of any golf course, and this was alleviated although EBITDA went down, and earnings were considerably compromised. We had to ask for funding through bank loans and make use of the tools implemented by the government for this type of problem, but this issue was resolved reasonably well”. (Roberto #3)

“In the year 2020, more balls were issued in the practice field, more green fees were obtained, more carts were hired, more everything was hired than in all of 2019 and there was no need to close for two months; what I mean is that as soon as the club reopened, business surged, this is a reality and something that unfortunately did not occur in other sectors”. (Juan #4)

“Then when the period of home arrest was over, people could come again. We can even confirm an increase in memberships of close to 14%”. (Lucas #5)

“As golf is played outdoors, there is no sharing of equipment, distances can be kept, there is no need for indoor installations, that is, someone could pull up in their car, play 18 holes, and drive back home without having touched anything other than their own equipment and been more than 2 m away from the other person playing. This meant that courses could open fairly quickly and that the assistance level was high from the beginning”. (Roberto #3)

3.2.2. Maintenance of Facilities

“So that you can imagine the situation, everything has its good side. If I am honest, at first we had time to carry out some maintenance work on the green (what we call cultural tasks), actions that with the players, with the course open are very difficult… In this sense, it was great. We had time to aerate and check greens… to do lots of things which are more difficult when the course is open. And, in second place, the closing of golf courses was beneficial. It is not the same when a golf club where 130,000 people play per year than when suddenly nobody steps on the green. The lawn was in great condition when the players returned. From this perspective, it was good”. (Juan #4)

“Because during the time when you could not play, all we did was maintenance (…) We did maintenance work using reduced human resources because with the earnings received during this period, we could not do everything”. (Lucas #5)

3.2.3. Communication with Interested Parties

“Luckily a protocol was created along with the different associations, federation, and government, such that we all acted in parallel. We even checked on one another by saying: “Hey, don’t take the covers off the holes”. We even said things like: “Hey, someone in Andalusia is doing this, will someone call them please”. (Carlos #1)

“The main difference in the world of golf is that we were extremely lucky as all institutions -clubs, federations, managerial associations, and greenkeeper associations—worked really hard together to draw up protocols that were definitely a reference at the national level of how things had to done to make things as safe as possible”. (Pedro #2)

“During the strict lockdown, communication was on the one hand with your workers about how the situation was and the gradual changes in the club, but also with the club members about what we proposed: “Dear Member, you are at home but we are here taking care of the club, keeping it alive so that when you can come back you will find it how you left it”. It is also true that there was almost daily news from the club, challenges, games, pictures … that is, it was constant communication”. (Pedro #2)

“It is essential to keep everyone informed about what is being done and what is not being done, both starting from the staff and the customers, suppliers, contract firms, etc., as they demand this… if they are well-informed everything works better (…) I feel that also transparency, I think that describing things as they are helps and benefits the organization”. (Roberto #3)

“The priority was absolute safety. Indeed, the cafeteria firm was the one that suffered most, because the elderly player, who would have a coffee after a round, will now go straight home, and that is the end of coffee sales. This functioning was indeed something different (…). It was not so much because of complying with the norms, the truth is the player has not complained about this but rather players grumbled and asked if the norms could be modified: “Hey when are you going to stop this? When are you going to remove the hole covers?” (Carlos #1)

“During the deepest part of home confinement, we had to seek support from the members who continued to pay the club their subscription with practically no exception or complaints. There were two or three people who did not agree and dropped out, but this was minimal”. (Lucas #5)

3.2.4. Design of Safety Protocols

“During the lockdown, the challenge was to maintain the club, see how this would affect it, how it could affect revenues, and make case scenarios considering the possibility of complaints or the rights the members would have because of those closed months and then, also, all the situation of the workers: job losses, unemployment, new workers…” (Roberto #3)

“Federations, managerial associations, greenkeeper associations… worked really hard together, creating protocols that were of sure reference at the national level of how things had to be done so that these would be as safe as possible. The most important aspect of management was without a doubt to transmit all these protocols to all users, that they should comprehend them, and fulfill them for the safety of everyone, which was the main goal. Then of course all these protocols kept changing practically from day to day, week to week, and some things could be done earlier than others”. (Pedro #2)

“The social situation suffered most negative impacts. The members wanted their cafeteria, as before the time of COVID. All events for which people could get together were the most restricted”. (Juan #4)

“With the pandemic, we had to take a 2.0 step of digitization in the club. And this step 2.0 is a great benefit. In effect, many members appreciated this despite all challenges and restrictions. We had not taken this step before because the main barrier is that the members are old, very old, and we would argue: “They are happy with how the system works” (…) But what we did in this period was: “Well now I have no option but to really implement the software so that members can book online, and have a protocol for bookings”. (Carlos #1)

“The first thing we tried was to set up an online booking system—something I would like to highlight is that if something good has come out of COVID (…) it is online booking for players. Online booking is here to stay. The truth is that all clubs were thinking about it, in installing it, and we found we were obliged”. (Juan #4)

3.3. Management Post-Pandemic

“Yes, from a corporate viewpoint, corporate events and tournaments are coming back. (…) The activity of social tournaments is carried out as normal in most cases (…) and we are practically at the level we were in 2019 in terms of level of activity”. (Roberto #3)

“Currently we are again seeing positive perspectives. 2021 was a good year without recovering all losses, that is, we have not made up everything lost during COVID. But it was still a good year economically, and the forecast for 2022 was optimistic, although I think that we are not going to be so optimistic as activity has slowed down a little”. (Roberto #3)

“We are struggling because increases in the cost of raw materials and energy have a very negative impact on us. I had ordered a ball machine and from one minute to the next they told me: “This has gone up by 20%, and if you don’t buy it within a week…” (Lucas #5)

“We found ourselves in a situation in which no club nor manager had prepared for because we can understand situations of economic, social problems, etc., but a pandemic of this type… this has not been studied at business schools. And I think that the capacity of managers and the importance of associations for situations as difficult as what we have lived through have also been brought to light. This I think is one of the main lessons: that unity makes for strength”. (Pedro #2)

“The issue of digitization and also of establishing new norms of functioning, as, for example, the requirement for bookings whether online or not, the flow of people, information, the communication channels opened with members… I feel the general functioning of the club has improved”. (Roberto #3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Situation Pre-Pandemic

4.2. Situation during the Pandemic

4.3. Situation Post-Pandemic

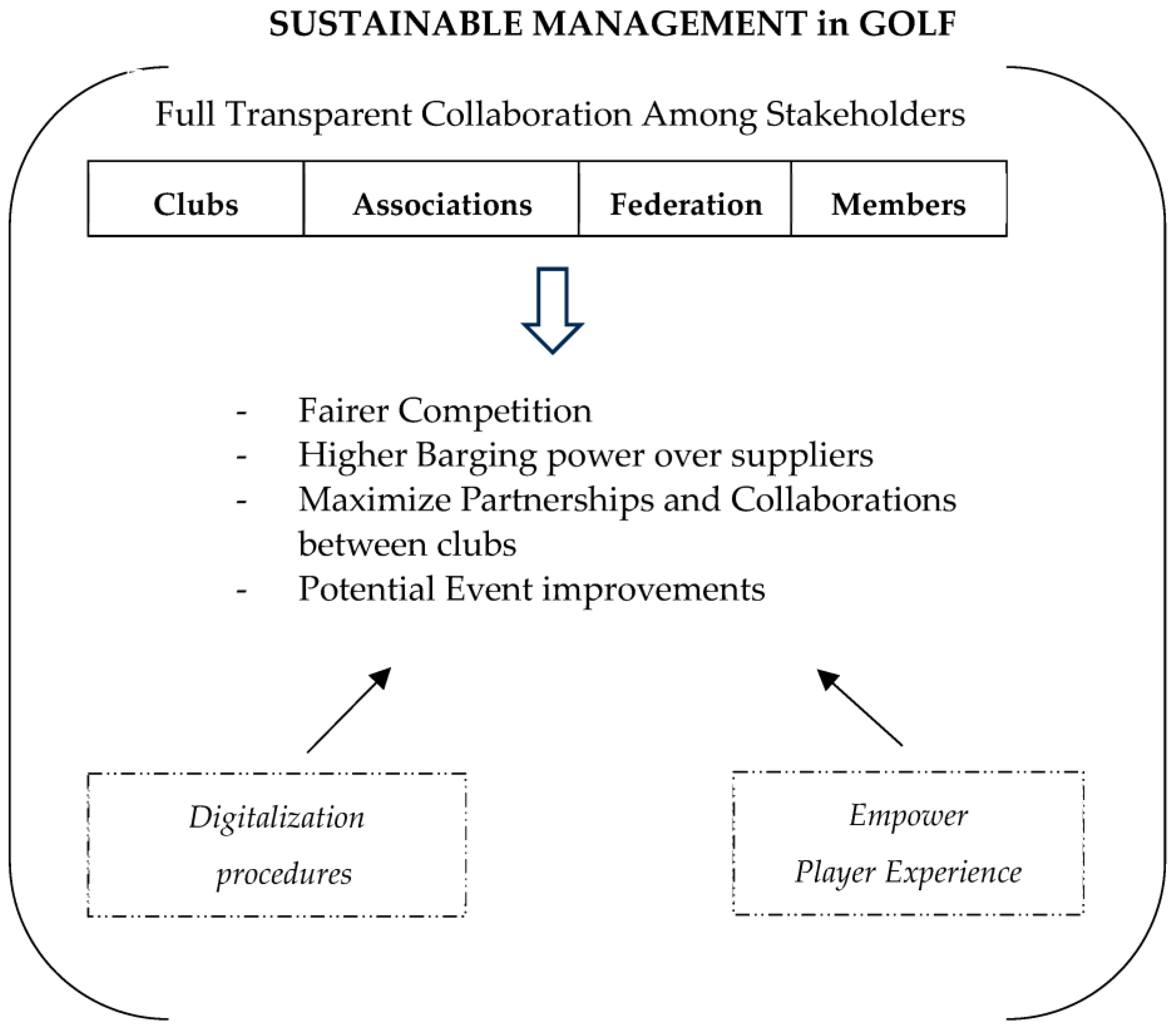

5. Conclusions and Implications

Implications

- (a)

- A higher bargaining power with suppliers (trying to, for example, minimize the high impact of inflation over some costs)

- (b)

- A fairer competence among clubs, especially in the face of the great threat that price-based competition could be, on a specific segment such as golf, traditionally focused on quality and the top socioeconomic level clients.

- (c)

- Better partnerships and collaborations between clubs. Particularly those clubs with a mixed business model (i.e., pay to play and membership model) can take advantage of the establishment of such agreements to provide to their members “other playing options” when they are unable to offer playing time at their facility due to club massification. During the conducted interviews at the current research, it was mentioned how a few clubs in Spain have this type of agreement, with positive client feedback.

- (d)

- Potential organization of new events. Sharing resources and efforts among stakeholders would open the potential for new event opportunities that were not in place due to economic or personal limitations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Tascón, M.; Mendaña-Cuervo, C.; Sahelices-Pinto, C.; Magaz-González, A.-M. Repercusión En La Calidad de Vida, Salud y Práctica de Actividad Física Del Confinamiento Por Covid-19 En España (Effects on Quality of Life, Health and Practice of Physical Activity of Covid-19 Confinement in Spain). Retos 2022, 42, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture and Sports. Sports Statistics Yearbook 2023; Spanish Sports Council: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, C.; Feiler, S.; Llopis-Goig, R.; Elmose-Østerlund, K. Characteristics of European Sports Clubs. A Comparison of the Structure, Management, Voluntary Work and Social Integration among Sports Clubs across Ten European Countries; University of Southern Denmark: Odense, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis-Goig, R.; Vilanova, A. Sport Clubs in Europe. Sports Economics, Management and Policy. In Sport Clubs in Europe; Breuer, C., Hoekman, R., Nagel, S., van der Werff, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Predicción Económica. Evaluación Del Impacto Económico Del Golf En La Comunidad de Madrid. Available online: http://www.mygolfway.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/EIEGOLF-2019.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Instituto de Empresa University. El Golf Como Catalizador de La Actividad Económica En España. Available online: /https://www.rfegolf.es/ArtculosDocumento/COMIT%C3%89%20RFEG/RFEG%202020/Estudio%20impacto%20econ%C3%B3mico%20golf%20en%20Espa%C3%B1a%202020/INFORME%20GOLF%20IE%20-%20AECG%20-%20RFEG%20-%20DEF.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Lera-López, F.; Ollo-López, A.; Rapún-Gárate, M. Sports Spectatorship in Spain: Attendance and Consumption. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadou, P.; Hill, B. Raising Environmental Responsibility and Sustainability for Sport Events: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Event Manag. Res. 2015, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Weed, M. The Role of the Interface of Sport and Tourism in the Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csobán, K.; Serra, G. The Role of Small-Scale Sports Events in Developing Sustainable Sport Tourism—A Case Study of Fencing. Appl. Stud. Agribus. Commer. 2014, 8, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshkar, S.; Dickson, G.; Ahonen, A.; Swart, K.; Addesa, F.; Epstein, A.; Dodds, M.; Schwarz, E.C.; Spittle, S.; Wright, R.; et al. The Effects of Coronavirus Pandemic on the Sports Industry: An Update. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2021, 9, e964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skille, E.Å. Understanding Sport Clubs as Sport Policy Implementers. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2008, 43, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, K.; Randle, E.; Donaldson, A.; Seal, E.; Burnett, D.; Thorn, L.; Forsdike, K.; Nicholson, M. Returning to Sport after a COVID-19 Shutdown: Understanding the Challenges Facing Community Sport Clubs. Manag. Sport Leis. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Sports Commission. Return to Sport. Available online: https://www.sportaus.gov.au/return-to-sport (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Orden SND/399/2020, de 9 de Mayo, paral Flexibilización de Determinadas Restricciones de Ámbito Nacional, Establecidas Tras Lla Declaración del Estado de Alarma en Aplicación de La Fase 1 del Plan para la Transición Hacia Una Nueva Normalidad. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2020/05/09/snd399 (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Royal Spanish Federation of Golf; Autonomic Federations of Golf; Spanish Association of Golf Courses; Spanish Association of Greenkeepers; Spanish Association of Golf Managers; Association of Golf Professionals. Protocolo Apertura Deporte del Golf. Available online: http://www.rfegolf.es/ArtculosDocumento/COMIT%C3%89%20RFEG/RFEG%202020/Documentaci%C3%B3n%20coronavirus/2020%20Protocolo%20apertura%20golf%20covid%2019.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Spanish Sports Council. Protocolo Básico Para la Vuelta a los Entrenamientos y el Reinicio de las Competiciones Federadas y Profesionales. Available online: https://www.csd.gob.es/sites/default/files/media/files/2020-05/CSD.%20GTID.%20Protocolo%20sanitario%20para%20el%20deporte.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Heredia, J.D. Critical Realism: An Alternative in Social Analysis. Soc. Econ. 2016, 1, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Urcia, I.A. Comparisons of Adaptations in Grounded Theory and Phenomenology: Selecting the Specific Qualitative Research Methodology. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0761919711. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, J.L.; Gallardo, L.; Burillo, P.; Gallardo, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Plaza-Carmona, M. A Qualitative Vision of Artificial Turf Football Fields: Elite Players and Coaches. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2013, 35, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- León-Quismondo, J.; García-Unanue, J.; Burillo, P. Best Practices for Fitness Center Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Vision. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cañamero, S.; Gallardo, L.; Ubago-Guisado, E.; García-Unanue, J.; Felipe, J.L. Causes of Customer Dropouts in Fitness and Wellness Centres: A Qualitative Analysis. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2018, 40, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Napton, D.E.; Laingen, C.R. Expansion of Golf Courses in the United States. Geogr. Rev. 2008, 98, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R&A. Golf Around the World. Available online: https://www.where2golf.com/documents/5/GAW_2019_Edition_3_hi.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Robinson, P.G.; Foster, C.; Murray, A. Public Health Considerations Regarding Golf during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e001089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, C.; Kurscheidt, M. Membership versus Green Fee Pricing for Golf Courses: The Impact of Market and Golf Club Determinants. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Gómez, V.; García-García, Ó.; Gambau i Pinasa, V.; Rial-Boubeta, A. Characterization of Profiles as Management Strategies Based on the Importance and Valuation That Users Give to the Elements of the Golf Courses. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. Understanding Business Cycles. In Essential Readings in Economics; Estrin, S., Marin, A., Eds.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 1995; pp. 306–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan-Canbolat, E.; Beraha, A. Evolutionary Stable Strategies for Business Innovation and Knowledge Transfer. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2019, 3, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D.; Stas, J.; Feller, K.; Knox, W. COVID-19: Return to Youth Sports. Sports Innov. J. 2020, 1, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamin, M. Counting the Cost of COVID-19. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2020, 12, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huth, C.; Billion, F. Acceptance and Economic Impact of the First COVID-19 Lockdown from Golf Clubs’ Point of View. Golf Sci. J. 2022, 10, 21405. [Google Scholar]

- Clem, T.N.; Ravichandran, S.; Karpinski, A.C. Understanding Golf Country Club Members’ Loyalty: Factors Affecting Membership Renewal Decisions. FIU Hosp. Rev. 2013, 31, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bodet, G. Loyalty in Sport Participation Services: An Examination of the Mediating Role of Psychological Commitment. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, Y.O.; Tabben, M.; Hassoun, K.; Al Marwani, A.; Al Hussein, I.; Coyle, P.; Abbassi, A.K.; Ballan, H.T.; Al-Kuwari, A.; Chamari, K.; et al. Resuming Professional Football (Soccer) during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Country with High Infection Rates: A Prospective Cohort Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J. Impact of COVID-19: A Qualitative Study Golfing Activities for Sports Tourism Management in Terengganu. BIMP EAGA J. Sustain. Tour. Dev. 2021, 10, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrubin, D.; Wiese, M.; Bohinc, B. An Outbreak of COVID-19 Associated with a Recreational Hockey Game—Florida, June 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1492–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brlek, A.; Vidovič, Š.; Vuzem, S.; Turk, K.; Simonović, Z. Possible Indirect Transmission of COVID-19 at a Squash Court, Slovenia, March 2020: Case Report. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Han, S.H.; Rhee, J.-Y. Cluster of Coronavirus Disease Associated with Fitness Dance Classes, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1917–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billion, F. Golfmarkt Deutschland 2019; SOMMERFELD AG: Edewecht, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Valcarce-Torrente, M.; Gálvez-Ruiz, P.; García-Fernández, J. The Spanish Fitness Industry and the Digital Transformation. In The Digital Transformation of the Fitness Sector: A Global Perspective; García-Fernández, J., Valcarce-Torrente, M., Mohammadi, S., Gálvez-Ruiz, P., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.R. Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends for 2021. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2021, 25, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.; Olsson, M.R.; Vitestam, M. Covid-19 and Outdoor Recreation Management: Increased Participation, Connection to Nature, and a Look to Climate Adaptation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 36, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Morales, S.-O. Innovation as Recovery Strategy for SMEs in Emerging Economies during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 57, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, C.L.; Ritter, T. Preparing Your Business for a Post-Pandemic World. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/04/preparing-your-business-for-a-post-pandemic-world (accessed on 4 September 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macías, R.; Bonal, J.; León-Quismondo, J.; Iván-Baragaño, I.; del Arco, J.; Burillo, P.; Fernández-Luna, Á. Golf Club Management Challenges towards Sustainability: Opportunities and Innovations during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813657

Macías R, Bonal J, León-Quismondo J, Iván-Baragaño I, del Arco J, Burillo P, Fernández-Luna Á. Golf Club Management Challenges towards Sustainability: Opportunities and Innovations during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Perspective. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813657

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacías, Ricardo, José Bonal, Jairo León-Quismondo, Iyán Iván-Baragaño, Javier del Arco, Pablo Burillo, and Álvaro Fernández-Luna. 2023. "Golf Club Management Challenges towards Sustainability: Opportunities and Innovations during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Perspective" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813657

APA StyleMacías, R., Bonal, J., León-Quismondo, J., Iván-Baragaño, I., del Arco, J., Burillo, P., & Fernández-Luna, Á. (2023). Golf Club Management Challenges towards Sustainability: Opportunities and Innovations during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Perspective. Sustainability, 15(18), 13657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813657