Ecotourism Development in the Russian Areas under Nature Protection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecotourism and PAs

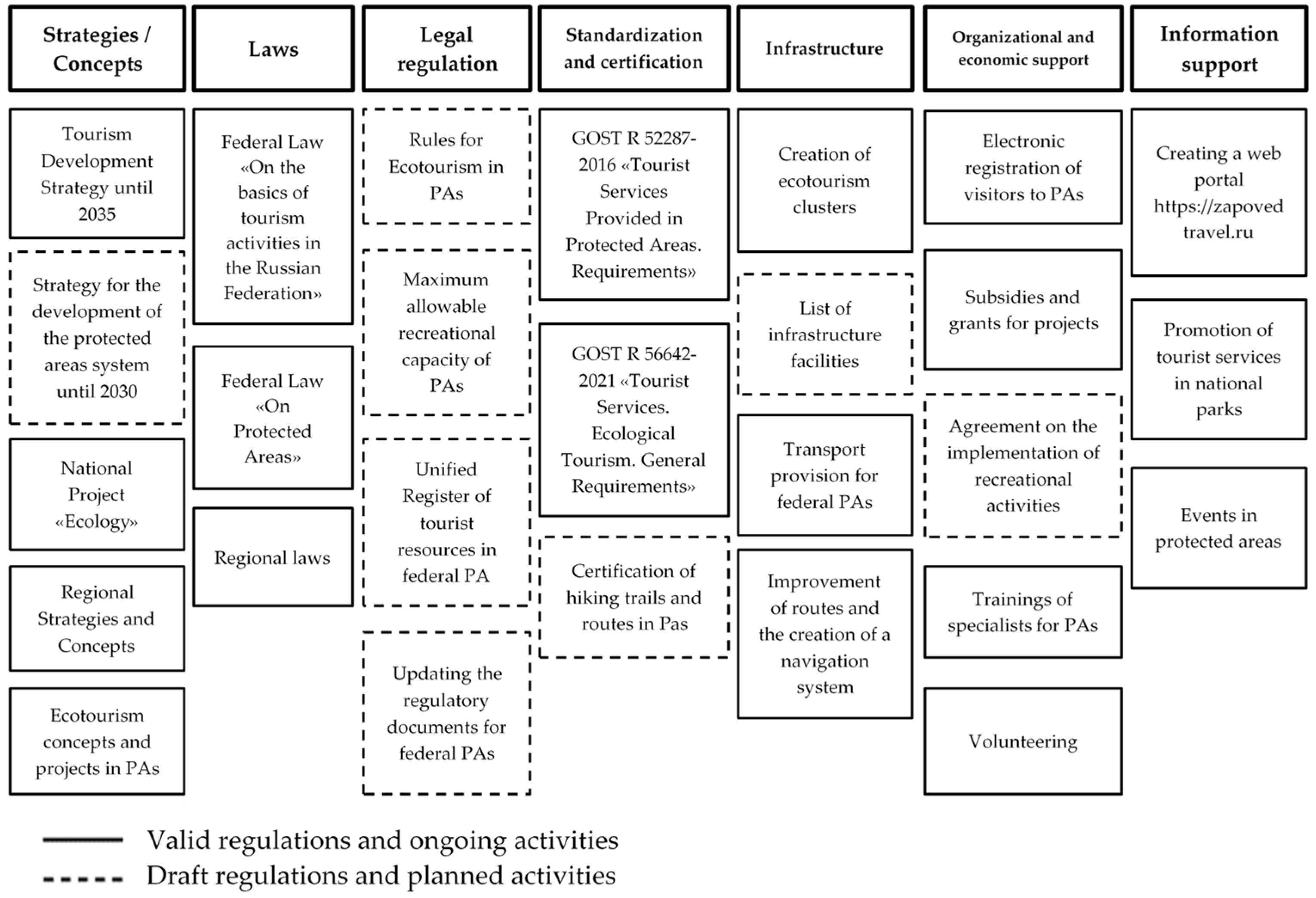

2.2. The Russian Approach to Ecotourism Development in PAs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. PAs as Centers of Ecotourism Development

3.2. Studied National Parks

3.2.1. Zabaikalsky National Park

3.2.2. Tunkinsky National Park

3.3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

- (1)

- In ZNP, 58% of visitors come from regions of Russia and some foreign countries. The majority of foreign visitors are organized groups from neighboring countries such as Mongolia and China. However, the total share of foreign tourists is insignificant. Nearly 47% of visitors to the park are aged between 18 and 35 years old, with 31.3% being in the 36–50 age range. Approximately 63.4% of tourists choose to visit the park during the warm season, which is from July to September. Figure 5 shows that the Lake Baikal coast has the highest photoactivity in ZNP.

- (2)

- Around 90% of the visitors to the TNP arrive from outside Buryatia, mainly from neighboring regions, and the share of foreign tourists is insignificant. The TNP attracts visitors of all ages. A total of 32% of visitors fall in the age group of 18–30 years, 26% are between 31 and 40, 17% are 41–50, and 13.2% are above 50 years old. From May to October, which marks the warm season, almost 59% of visitors prefer to relax in the TNP. The majority of photos in the TNP are taken around settlements, where guest houses, popular excursion objects, eco-trails, and mineral springs are located (refer to Figure 6).

- D1. Management

- D2. Functional Zoning

- D3. Concept (or project) for developing ecotourism in national parks.

- D4. Infrastructure

- D5. Involving local people in tourism services

- D6. Funding

- D7. Promoting ecotourism

- D8. Monitoring

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strategy for the Development of Tourism in the Russian Federation until 2035. Available online: https://strategy24.ru/rf/news/strategiya-razvitiya-turizma-v-rossiyskoy-federatsii-do-2035-goda (accessed on 23 December 2022). (In Russian).

- Benefits Beyond Boundaries. In Proceedings of the Vth IUCN World Parks Congress, Durban, South Africa, 8–17 September 2003; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2005; p. 306.

- What is Ecotourism? Available online: https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Bibliometric analysis and literature review of ecotourism: Toward sustainable development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, R.; Dash, M. Ecotourism, biodiversity conservation, and local livelihoods: Understanding the convergence and divergence. Int. J. Geoheritage Park. 2022, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Mingzhu, L.; Bu, N.; Pan, S. Regulatory frameworks for ecotourism: An application of Total Relationship Flow Management Theorems. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, K. Code Green: Experiences of a Lifetime; Lonely Planet Publications: London, UK, 2006; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Santarem, F.; Campos, J.C.; Pereira, P.; Hamidou, D.; Saarinen, J.; Brito, J.C. Using multivariate statistics to assess ecotourism potential of waterbodies: A case-study in Mauritania. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouboter, D.A.; Kadosoe, V.S.; Ouboter, P.E. Impact of ecotourism on abundance, diversity and activity patterns of medium-large terrestrial mammals at Brownsberg Nature Park, Suriname. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhandzhugazova, E.; Iljina, E.; Latkin, A.; Davidivich, A.; Siganova, V. Problems of Development of Ecological Tourism on the territory of National Parks of Russia. Ekoloji 2019, 28, 4913–4917. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Compendium of Best Practices and Recommendations for Ecotourism in Asia and the Pacific; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012; p. 128.

- Best Practices Ecological Tourism Subjects of Russian Federation; REU Them G.V.Plekhanova: Moscow, Russia, 2018; p. 168. (In Russian)

- Balmford, A.; Green, J.M.H.; Anderson, M.; Beresford, J.; Huang, C.; Naidoo, R.; Walpole, M.; Manica, A. Walk on the Wild Side: Estimating the Global Magnitude of Visits to Protected Areas. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecotourism Global Market Report—2022. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/ecotourism-global-market-report (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.; Lawton, L. A new visitation paradigm for protected areas. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Primack, R.B.; Ma, K.; Zhou, Z.-Q. A Chinese approach to protected areas: A case study comparison with the United States. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210-B, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, H.; Teshome, E.; Asteray, M. Assessing protected areas for ecotourism development: The case of Maze National Park, Ethiopia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 8, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayneko, D.; Dayneko, A.; Dayneko, V. Analysis of Ecological tourism development in Russia and USA. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 311, 09003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forje, G.W.; Tchamba, M.N. Ecotourism governance and protected areas sustainability in Cameroon: The case of Campo Ma’an National Park. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-C.; Lin, J.-C. Benefits beyond boundaries: A slogan or reality? A case study of Taijiang National Park in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, I.Z.; Öztürk, A. Identifying, Monitoring, and Evaluating Sustainable Ecotourism Management Criteria and Indicators for Protected Areas in Türkiye: The Case of Camili Biosphere Reserve. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilina, N.R. The Role of Nature Reserves in the System of Russian Specially Protected Natural Areas: History and Modernity. In Russia in the Surrounding World: 2010. Sustainable Development: Ecology, Politics, Economics. Analytical Yearbook; MNEPU Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2010; pp. 121–146. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zvyagina, E.S.; Rybakova, M.V. Ecotourism as an environmentally-responsible practice in the management of specially protected natural territories of the Russian Federation. Public Adm. E-J. 2015, 48, 50–65. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Belenko, N.G.; Kuliev, T.B. Problems and prospects for the development of ecological tourism in the Russian Federation in the context of a new model for managing specially protected natural areas. In Proceedings of the IV International Scientific and Practical Conference “Dobrodeev Readings—2020“, Moscow, Russia, 9 December 2020. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- State Report “On the State and Protection of the Environment of the Russian Federation in 2021”; Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia; Lomonosov Moscow State University: Moscow, Russia, 2022; p. 686. (In Russian)

- Golubchikov, Y.N.; Kruzhalin, K.V.; Khlynov, A.Y.; Khlynova, N.V. Eco-tourism within protected areas. Vestn. Natl. Tour. Acad. 2014, 2, 19–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, J.V.; Bogoliubova, N.M.; Shirin, S.S. Ecological tourism in the state image policy structure. Experience and problems of modern Russia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkrtchan, G.M.; Blam, I.Y. Ecotourism and Conservation in Time of COVID 19 Pandemic and beyond. ECO J. 2021, 2, 25–39. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirova, A.V. Ecological tourism in specially protected natural territories. Bull. South Ural. State Univ. Ser. “Law” 2021, 20, 109–114. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabalina, N.V.; Nikanorova, A.D.; Aleksanrova, E.E. Ecotourism: Features and problems of development in Russia. Univ. Tour. Serv. Assoc. Bull. 2021, 15, 4–14. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyeva, M.I. The legal definition of the concept of ecotourism. Lex Russ. 2020, 73, 34–52. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST P 56642-2021. Tourism Services. Ecological Tourism. General Requirements. Federal Agency for Technical Regulation and Metrology: Moscow, Russia, 2021. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200182520 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Maksanova, L.B.Z.; Kharitonova, O.B.; Andreeva, A.M. Creating models of integrated development of ecotourism in Russian protected areas. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 885, 012056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidlovskaya, Y.A. Evolution of functional zoning of national park Curonian Spit. Vestn. Immanuel Kant Balt. Fed. Univ. 2015, 1, 72–78. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Budaeva, D.G.; Maksanova, L.B.Z.; Sharaldaeva, V.D. Evolution of functional zoning of the Tunkinsky national park. Proc. Russ. Geogr. Soc. 2022, 154, 66–76. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kop’yova, А.V.; Maslovskaya, O.V.; Petrova, E.S.; Ivanova, O.G. Formation of a Model of the Functional-Spatial Organization of the Ecological Route. Ojkumena Reg. Res. 2021, 2, 74–81. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Report “On the State and Protection of the Environment of the Russian Federation in 2020"; Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia; Lomonosov Moscow State University: Moscow, Russia, 2021; p. 864. (In Russian)

- Stishov, M.S.; Dudley, N. Protected Natural Territories of the Russian Federation and Their Categories; WWF: Moscow, Russia, 2018; p. 248. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Strategy for the Management of National Parks in Russia; Publishing House of the Center for the Protection Wildlife: Moscow, Russia, 2002; p. 36. (In Russian)

- Astanin, D.M. Typology of functional zoning of national and natural parks. Arhit. Izv. Vuzov 2018, 1, 61. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Maksakovskaya, N.S.; Maksakovsky, N.V. National parks of Russia as the basis of the environmental framework of the country's territory and a resource for tourism development. Bull. Mosc. City Pedagog. Univ. Ser. Nat. Sci. 2017, 1, 9–20. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zapovednoe Podlemorye. Available online: https://zapovednoe-podlemorye.ru/ (accessed on 1 February 2023). (In Russian).

- Tunkinsky National Park. Available online: http://tunkapark.ru (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Luzhkova, N.M.; Myadzelets, A.V.; Sedykh, S.A. The historical, geographical and landscape ecological aspects of development in Zabaikal national park. Bull. Buryat Sci. Cent. Sib. Branch Russ. Acad. Sci. 2015, 2, 207–216. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Snow Leopard. Available online: https://wwf.ru/help/species/snow-leopard/ (accessed on 20 January 2023). (In Russian).

- Maksanova, L.; Bardakhanova, T.; Lubsanova, N.; Budaeva, D.; Tulokhonov, A. Assessment of losses to the local population due to restrictions on their ownership rights to land and property assets: The case of the Tunkinsky National Park, Russia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, D. The New Paradigm for Protected Areas: Implications for Managing Visitors in Protected Areas. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Monitoring and Management of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas, Rapperswil, Switzerland, 13–17 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I. Review of the approaches for assessing protected areas’ effectiveness. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Reports. About the State of Lake Baikal and Measures for Its Protection. Available online: https://www.mnr.gov.ru/docs/gosudarstvennye_doklady/o_sostoyanii_ozera_baykal_i_merakh_po_ego_okhrane/ (accessed on 15 January 2023). (In Russian)

- Federal State Statistics Service. Available online: https://burstat.gks.ru/ (accessed on 1 February 2023). (In Russian).

- Euronews Showed a Story about a Buryat Village Dug in with Three Ditches. Available online: https://www.baikal-daily.ru/news/16/394160/ (accessed on 1 February 2023). (In Russian).

- Ovdin, M.E.; Ananin, A.A. Concerning the Development of Ecological Tourism in Protected Areas Managed by FSBI “Zapovednoe Podlemorye”. BSU Bull. Biol. Geogr. 2021, 3, 49–55. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 2399 Dated December 31, 2020 “On Approval of Types of Activities Prohibited in the Central Ecological Zone of the Baikal Natural Area”. Available online: https://base.garant.ru/400167820/ (accessed on 23 December 2022). (In Russian).

- Ulanova, O.V.; Alberg, N.I. The Concept of Sustainable Management of Municipal Solid Waste in the Territory of the Zabaikalsky National Park; Publishing House “Academy of Natural Science”: Moscow, Russia, 2020; p. 122. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lubsanova, N.B.; Maksanova, L.B. Prospects for the implementation of a separate waste collection system in specially protected areas by the example of the Tunkinsky National Park. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 941, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovenko, I.M.; Voronina, A.B. Especially protected natural territories as object recreational activity. Sci. Notes Vernadsky Crime. Fed. Univ. Geogr. Geol. 2015, 1, 41–60. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Mikheeva, A.S.; Maksanova LB-Zh Abidueva, T.I.; Bardakhanova, T.B. Ecological-Economic Problems and Conflicts in Nature Management in the Central Ecological Zone of the Baikal Natural Territory (Republic of Buryatia). Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2016, 5, 210–217. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Timms, D.F. Renegotiating Peasant Ecology: Responses to Relocation from Celaque National Park, Honduras; Indiana University: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, V.A.; Vorobyevskaya, E.L.; Kirillov, S.N. Modern nature resource management in the Tunkinsky national park. InterCarto InterGIS 2022, 28, 362–375. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksanova, L.; Ivanova, S.; Budaeva, D.; Andreeva, A. Public-Private Partnerships in Ecotourism Development in Protected Areas: A Case Study of Tunkinsky National Park in Russia. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2020, 11, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Exchange Rates of the Central Bank of Russia on 1 Jan 2023. Available online: https://cbr.ru/currency_base/daily/?UniDbQuery.Posted=True&UniDbQuery.To=01.01.2023 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Gilroy, L.; Kenny, H.; Morris, J. Parks 2.0: Operating State Parks through Public-Private Partnerships; Reason Foundation: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

| Basic Information | Zabaikalsky National Park | Tunkinsky National Park |

|---|---|---|

| Year of creation | 1986 | 1991 |

| Purpose of creation | Preserving the unique natural complex of Lake Baikal basin and creating conditions for the development of organized recreation | Preservation of unique ecosystems of the Eastern Sayan and Khamar-Daban spurs |

| Park model | Wildlife Park | Park of intermediate character |

| Area, thous. ha | 269.1 | 1183.7 |

| Land Fund | 100%—PA lands | 90.6%—PA lands, 9.4%—lands of other owners |

| Recreational area, % of the total area | 55.1 | 63.3 |

| Number of routes | 12 | 50 |

| Mineral Springs | 3 | 12 |

| Natural Monuments | 5 | 12 |

| Historical and Architectural Monuments | - | 24 |

| Archaeological monuments | 13 | 16 |

| Sites of scientific tourism | - | 2 (solar observatories) |

| Settlements/number of residents | 3/112 people | 35/20,106 people |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maksanova, L.; Bardakhanova, T.; Budaeva, D.; Mikheeva, A.; Lubsanova, N.; Sharaldaeva, V.; Eremko, Z.; Andreeva, A.; Ayusheeva, S.; Khrebtova, T. Ecotourism Development in the Russian Areas under Nature Protection. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813661

Maksanova L, Bardakhanova T, Budaeva D, Mikheeva A, Lubsanova N, Sharaldaeva V, Eremko Z, Andreeva A, Ayusheeva S, Khrebtova T. Ecotourism Development in the Russian Areas under Nature Protection. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813661

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaksanova, Lyudmila, Taisiya Bardakhanova, Darima Budaeva, Anna Mikheeva, Natalia Lubsanova, Victoria Sharaldaeva, Zinaida Eremko, Alyona Andreeva, Svetlana Ayusheeva, and Tatyana Khrebtova. 2023. "Ecotourism Development in the Russian Areas under Nature Protection" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813661