The Market Responses of Ice and Snow Destinations to Southerners’ Tourism Willingness: A Case Study from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ice–Snow Tourism

2.2. Willingness to Participate in Ice–Snow Tourism

2.3. Meeting the Market’s Willingness for Ice–Snow Tourism

3. Research Method

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Selecting Study Areas

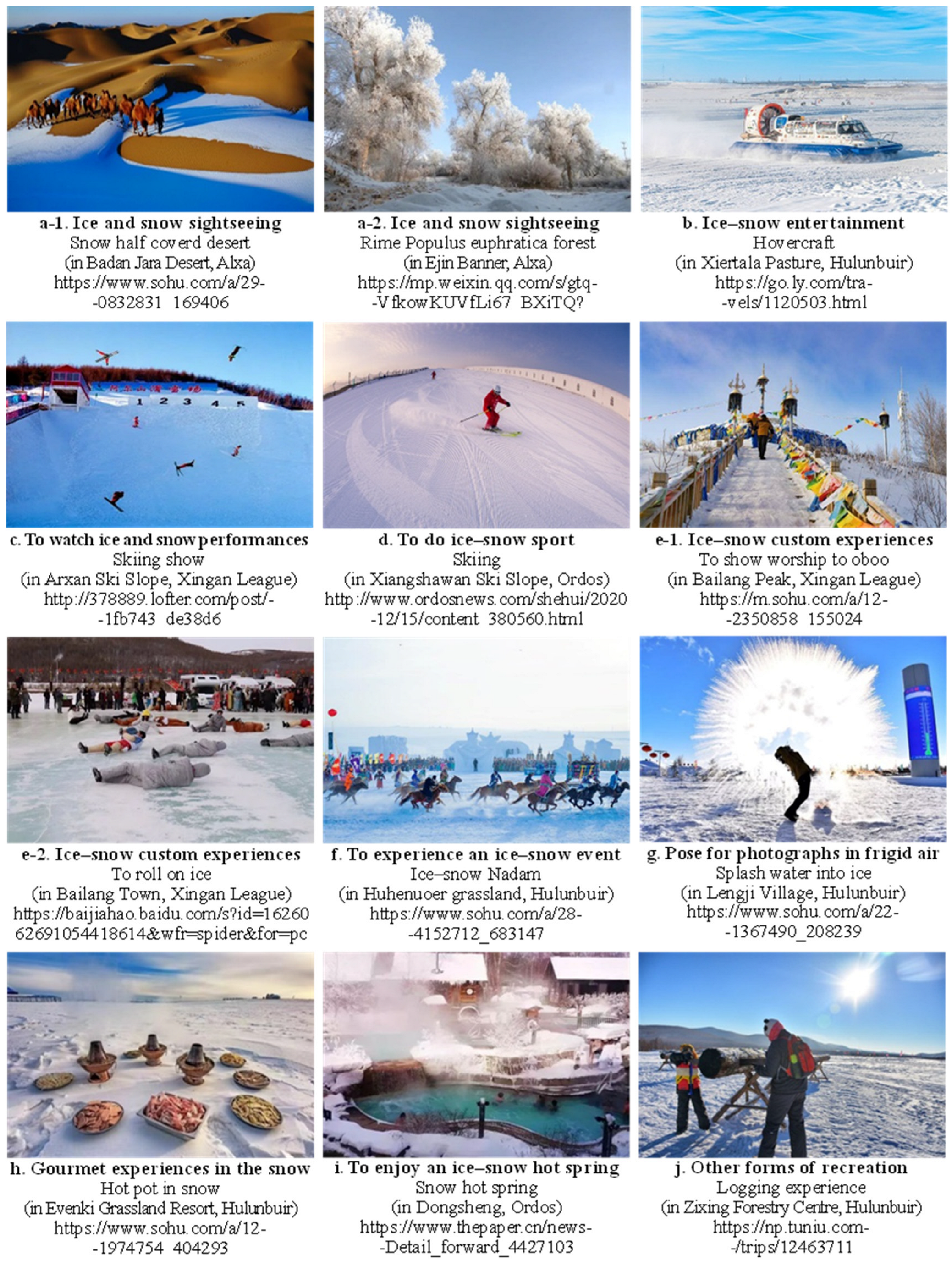

3.3. Summarizing Ice–Snow Tourism Activities

3.4. Investigating Respondents’ Ice–Snow Tourism Willingness after the Winter Olympics

3.5. Analyzing the Effects of Tourism Activities on Inducing Respondents’ Willingness

3.6. Analyzing Tourism Activities’ Availability Effects on Meeting Respondents’ Willingness

3.6.1. Analyzing the Effects of the Number of Available Tourism Activities

3.6.2. Analyzing the Effects of the Expenses for Available Tourism Activities

4. Result and Analysis

4.1. Respondents’ Willingness to Travel to the Study Areas for Ice–Snow Tourism

4.2. Effects on Inducing Respondents’ Ice–Snow Tourism Willingness

4.2.1. Effects of Each Category of Activities in General

4.2.2. Activity Category Effects by Respondent Willingness Level

4.3. Effects on Meeting Respondents’ Ice–Snow Tourism Willingness

4.3.1. Effects of the Number of Available Tourism Activities

4.3.2. Effects of Required Expenses for Available Tourism Activities

- (1)

- Required expenses per capita

- (2)

- Respondents’ willingness to pay

- (3)

- Effects of a reasonable composition of expense levels for available tourism activities

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Marketing Ice–Snow Tourism to Vitalize Winter Destinations in the North

5.1.2. Marketing to Induce Southerners’ Ice–Snow Tourism Willingness

5.1.3. Market Strategies for Meeting Southerners’ Ice–Snow Tourism Willingness

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Conclusions

5.4. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexandrova, A.Y.; Aigina, E.V.; Minenkova, V.V. The Impact of 2014 Olympic Games on Sochi Tourism Life Cycle. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 10, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, Z.M.; Morozov, A.I. Formation of environmental heritage of Winter Olympic Games. Theory Pract. Phys. Cult. 2014, 1, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.P.; Hou, Z.F.; Wang, J.H.; Yuan, S.S. Research on the Development Characteristics of Ice and Snow Industry from the Perspective of Winter Olympic Heritage. Front. Sport Res. 2022, 4, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.C.; Li, Y.; Li, J.W.; Xia, B. Research on the comprehensive ice-snow tourism development mode in China. J. Chin. Ecotourism 2021, 11, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Snow and Ice Tourism Development Report (2022) Was Released: The Revenue of Ice and Snow Leisure Tourism Was Expected to Reach 323.3 Billion Yuan. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n20001280/n20067608/n20067635/c23922890/content.html (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Wu, L.M.; Feng, H.T. The Deep Integration of China’s Regional Ice-Snow Industry and Ecocultural Tourism under the Background of Beijing Winter Olympic Games: Taking Hunan as an Example. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 6736709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Q.S.; Xu, Y.M. Spatial differentiation pattern of the population and its influencing factors in the southeastern half of HU Huanyong Line. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Report on China’s Domestic Tourism Development. Available online: http://www.cntour.cn/h-nd-2491.html (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Big Data Report on China’s Ice and Snow Tourism Consumption. Available online: http://www.ctaweb.org.cn/cta/gzdt/202201/b862a90770a847e0a2d976c129422f85.shtml (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Lundmark, L.; Carson, D.A.; Eimermann, M. Who travels to the North? Challenges and opportunities for tourism. In Dipping in to the North: Living, Working and Traveling in Sparsely Populated Areas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Sun, J.; Huang, T.; Ge, Q. The Spatial Differentiation of the Suitability of Ice-Snow Tourist Destinations Based on a Comprehensive Evaluation Model in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Seekamp, E.; McCreary, A.; Davenport, M.; Kanazawa, M.; Holmberg, K.; Wilson, B.; Nieber, J. Shifting demand for winter outdoor recreation along the North Shore of Lake Superior under variable rates of climate change: A finite-mixture modeling approach. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 123, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evren, S.; Kozak, N. Competitive positioning of winter tourism destinations: A comparative analysis of demand and supply sides perspectives–Cases from Turkey. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, T.; Unseld, C. Winter tourism in Germany is much more than skiing! Consumer motives and implications to Alpine destination marketing. J. Vacat. Mark. 2018, 24, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, T.; Gartner, W.C. Winter tourism in the European Alps: Is a new paradigm needed? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M.T. The Attraction of the Mundane—How everyday life contributes to destination attractiveness in the Nordic region. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.C.; Zeng, R.; Yang, Y.Y.; Xu, S.Y.; Wang, X. High-quality development paths of ice-snow tourism in China from the perspective of the Winter Olympics. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.; Busuio, M.F. Development trends of mountain tourism and winter sports market, worldwide, in europe and in romania. Rom. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2021, 16, 138–144. Available online: http://www.rebe.rau.ro/RePEc/rau/journl/SU21/REBE-SU21-A13.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Steiger, R.; Damm, A.; Prettenthaler, F.; Proebstl-Haider, U. Climate change and winter outdoor activities in Austria. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 34, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesmana, H.; Sugiarto, S.; Yosevina, C.; Widjojo, H. A Competitive Advantage Model for Indonesia’s Sustainable Tourism Destinations from Supply and Demand Side Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, Y.; Paget, E.; Dimanche, F. Uncertain tourism: Evolution of a French winter sports resort and network dynamics. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.O. Applying discrete choice models to understand sport tourists’ heterogeneous preferences for Winter Olympic travel products. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 482–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, S.; Tešin, A. Mountain winter getaways: Excitement versus boredom. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davras, G.M. Classification of winter tourism destination attributes according to three factor theory of customer satisfaction. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22, 496–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, E.; Liu, J. The influence of high-speed rail on ice–snow tourism in northeastern China. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielinis, E.; Janeczko, E.; Takayama, N.; Zawadzka, A.; Słupska, A.; Piętka, S.; Lipponen, M.; Bielinis, L. The effects of viewing a winter forest landscape with the ground and trees covered in snow on the psychological relaxation of young Finnish adults: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, E.T.; Brownlee, M.T.; Bricker, K.S. Winter recreationists’ perspectives on seasonal differences in the outdoor recreation setting. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, M.; Federolf, P.A.; Nachbauer, W.; Kopp, M. Potential Health Benefits From Downhill Skiing. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glossary of Tourism Terms. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/glossary-tourism-terms (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Hall, C.M.; Stefánsson, Þ. Senses by seasons: Tourists’ perceptions depending on seasonality in popular nature destinations in Iceland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.H. Review and Prospect of China’s Ice-Snow Tourism Research in Recent 20 Years. The Frontiers of Society. Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipov, S.K.; Anosova, N.E.; Aladyshkin, I.V.; Kolomeyzev, I.V.; Ishankhodjaeva, Z.R. Ways of developing tourism logistics in the far north of Russia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 434, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.D.; Tishkov, S.V. Strategic Development Priorities for the Karelian Arctic Region in the Context of the Russian Arctic Zone Economic Space Integration. Arct. North 2022, 46, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.A.; Carson, D.B.; Eimermann, M. International winter tourism entrepreneurs in northern Sweden: Understanding migration, lifestyle, and business motivations. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrot, O.G.; Christensen, J.H.; Formayer, H. Greenland winter tourism in a changing climate. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 27, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacoş, I.B.; Gabor, M.R. Tourism economy. Mountain tourism: Quantitative analysis of winter destinations in Romania. Economics 2021, 9, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, G.; Stockigt, L.; Saarinen, J.; Fitchett, J.M. Adapting to climate change: The case of snow-based tourism in Afriski, Lesotho. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2021, 40, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaryan, L.; Fredman, P. Bridging outdoor recreation and nature-based tourism in a commercial context: Insights from the Swedish service providers. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 17, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, C.; Truant, E.; Bonadonna, A. Mountain tourism and motivation: Millennial students’ seasonal preferences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2461–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. UNWTO International Conference on Tourism and Snow Culture: Snow Experiences and Winter Traditions as Assets for Tourism Destinations. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/archive/asia/event/unwto-international-conference-tourism-and-snow-culture-snow-experiences-and-winter-traditions (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- International Report on Snow & Mountain Tourism. Overview of the Key Industry Figures for Ski Resorts. Available online: https://vanat.ch/international-report-on-snow-mountain-tourism (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Vanova, Z.; Afonina, M. Setting objectives and developing planning concepts as part of the process of design of Russian urban recreation areas (the social aspect). Procedia Eng. 2016, 165, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, C.; Turci, L. From ski to snow: Rethinking package holidays in a winter mountain destination. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; O’Mahony, B.; Gayler, J. Modelling the relationship between attribute satisfaction, overall satisfaction, and behavioural intentions in Australian ski resorts. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 764–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.; Øian, H.; Aas, Ø.; Tangeland, T. Affective and cognitive dimensions of ski destination images. The case of Norway and the Lillehammer region. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.; Vieru, M. International tourism demand to Finnish Lapland in the early winter season. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjørve, E.; Lien, G.; Flognfeldt, T. Properties of first-time vs. repeat visitors: Lessons for marketing Norwegian ski resorts. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdošíková, Z.L.; Gajdošík, T.; Kučerová, J. Slovak winter tourism destinations: Future playground for tourists in the carpathians. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M. A dynamic panel data analysis of snow depth and winter tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Xu, J.; Wei, X. Tourism destination preference prediction based on edge computing. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 5512008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göker, G. Flow Experience Study for Outdoor Recreation: Ilgaz Ski Area Case Study. J. Tour. Serv. 2022, 13, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghammer, A.; Schmude, J. The Christmas—Easter shift: Simulating alpine ski resorts’ future development under climate change conditions using the parameter ‘optimal ski day’. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirehie, M.; Gibson, H. Empirical testing of destination attribute preferences of women snow-sport tourists along a trajectory of participation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gené, J.; Sánchez-Pulido, L.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries, N. The economic sustainability of snow tourism: The case of ski resorts in Austria, France, and Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.M.; Salinas Fernandez, J.A.; Rodriguez Martin, J.A.; Ostos Rey, M.D.S. Analysis of tourism seasonality as a factor limiting the sustainable development of rural areas. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.; Posch, E.; Tappeiner, G.; Walde, J. The impact of climate change on demand of ski tourism-a simulation study based on stated preferences. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 170, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Vanhuele, M.; Pauwels, K. Mind-set metrics in market response models: An integrative approach. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P.; Davari, A.; Zolfagharian, M.; Paswan, A. Market orientation, positioning strategy and brand performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 81, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.Y. A reflection on the integration relationship between Kotler’s marketing theory and Ries’s market positioning theory. Commer. Times 2014, 17, 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, A. The discipline of the narrow focus. J. Bus. Strategy 1992, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rua, O.L.; Santos, C. Linking brand and competitive advantage: The mediating effect of positioning and market orientation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Priporas, C.V.; Stylos, N. ‘You will like it!’ using open data to predict tourists’ response to a tourist attraction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantola, A.; Gulati, R.; Zhelyazkov, P.I. External interfaces or internal processes? Market positioning and divergent professionalization paths in young ventures. Organ. Sci. 2023, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Amézaga, C. The Impact of YouTube in Tourism Destinations: A Methodological Proposal to Qualitatively Measure Image Positioning—Case: Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.M.; Liu, A.L.; Chen, T. Influencing factors and countermeasures of skiing resort development distribution: With inner Mongolia Municipality’s skiing tourism development as an example. Prog. Geogr. 2005, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.F.; Lv, J. Study on the development of Ice-snow tourism in Inner Mongolia. J. Inn. Mong. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 20, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.J.; Qi, X.M.; Zhang, S.L.; Hou, X.Y. Ice-snow tourism resources and utilization in Inner Mongolia. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2017, 31, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfen, R.M. Photograph’s role in tourism: Some unexplored relationships. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Sihite, J. ASEAN Tourism Destination: A Strategic Plan. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2018, 21, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, C.C.; Colman, A.M. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychol. 2000, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G. Regression Quantiles. Econometrica 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Q.T.; Zhao, H.; Ma, J.X.; Zang, C. A calculation method and its application on the matching degree of the water resources utilization and socioeconomic development. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2014, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.M.; Rennie, V.A. Pursuing pleasure: Consumer value in leisure travel. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 5, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Research on the Multidimensional Demand and Precise Supply of Ice and Snow Sports Public Services in the Post-Winter Olympics Period. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2022, 45, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Meng, S. The economic impacts of the 2018 Winter Olympics. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1303–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. Rural tourism preferences in Spain: Best-worst choices. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witting, M.; Bischof, M.; Schmude, J. Behavioural change or “business as usual”? Characterising the reaction behaviour of winter (sport) tourists to climate change in two German destinations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.; Posch, E.; Tappeiner, G.; Walde, J. Seasonality matters: Simulating the impacts of climate change on winter tourism demand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 2777–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannevig, H.; Gildestad, I.M.; Steiger, R.; Scott, D. Adaptive capacity of ski resorts in Western Norway to projected changes in snow conditions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3206–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. A study on the influencing factors of tourism demand from mainland China to Hong Kong. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, C.M.; Cheng, J.H.; Dai, J. Does tourism industry agglomeration reduce carbon emissions? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 30278–30293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzuhara, K.; Shibata, M.; Iguchi, J. Incidence of skiing and snowboarding injuries over six winter seasons (2012–2018) in Japan. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2021, 21, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, B.Q.; Jin, Y.Y. Residents’ ice and snow sports consumption dilemma and promotion strategy. Sports Cult. Guide 2019, 7, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheleznyak, O.Y. Winter city and the potential/space of Siberian identity. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 962, 032081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Pikkemaat, B. Winter sports tourism to urban destinations: Identifying potential and comparing motivational differences across skier groups. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 36, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benur, A.M.; Bramwell, B. Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, A.; Greuell, W.; Landgren, O.; Prettenthaler, F. Impacts of +2 °C global warming on winter tourism demand in Europe. Clim. Serv. 2017, 7, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Category | Subcategory/Number of Pictures | Total Number of Pictures |

|---|---|---|

| Ice and snow sightseeing (X′1) | (1) Appreciating natural snowscape/125; (2) appreciating architecture in snowfield/62; (3) appreciating ice and snow sculptures/49; (4) appreciating animals in snowfield/27; (5) appreciating natural ice–snow scenery/25; (6) appreciating natural icescape/10; (7) appreciating other distinct scenery in ice and snowfield/8; (8) appreciating artificial landscape decoration in snowfield/2; (9) appreciating manufacturing facilities in snow-fields */2 | 310 |

| Ice–snow entertainment (X′2) | (1) Gliding in snowfield with unpowered equipment /26; (2) snowmobiling/24; (3) gliding on ice with unpowered equipment/17; (4) playing with snow/15; (5) ice gaming/7; (6) making snowmen/5; (7) roaming on ice/3; (8) snow gaming/3; (9) playing with hovercraft on ice */2; (10) touching ice/1; (11) other entertainment in snowfield/9 | 112 |

| Watching ice and snow performance (X′3) | (1) Watching ice and snow folk show/35; (2) watching ice and snow art show/14; (3) watching ice and snow sport skill show/8; (4) watching fireworks display in ice and snow field/3 | 60 |

| Doing ice–snow sports (X′4) | (1) Snow skiing/18; (2) snow hiking/8; (3) playing ball game in snowfield/6; (4) skating/3; (5) winter swimming/3; (6) playing ball game on ice/2; (7) other ice and snow sport/3 | 43 |

| Ice–snow custom experience (X′5) | (1) Enjoying livestock sledding/19; (2) feeding animals in snowfield/4; (3) enjoying folk game in snowfield/3; (4) riding horse in snowfield/3; (5) riding camel in snowfield/2; (6) taking part in bonfire party in snowfield/2; (7) experiencing unique living facilities in snowfield/2; (8) experiencing opening up ice path */1; (9) experiencing other folk customs in snowfield/6 | 42 |

| Experiencing ice–snow events (X′6) | (1) Experiencing ice and snow sports events/17; (2) experiencing local traditional ice and snow festivals/10; (3) experiencing ice and snow tourism cultural festivals/9 | 36 |

| Posing for photographs in frigid air (X′7) | (1) Posing for photographs with snowscape/20; (2) posing for photographs with icescape/4; (3) posing for photographs with ice–snow scenery/2 | 26 |

| Gourmet experiences in snow (X′8) | (1) Having hot pot in snowfield/5; (2) having a picnic in snowfield/4; (3) tasting ethnic cuisine/2; (4) enjoying frozen fruit */1 | 12 |

| Enjoying ice–snow hot spring (X′9) | (1) Enjoying open-air hot spring in snowfield/8; (2) enjoying semi-open-air hot spring in snowfield */2 | 10 |

| Other recreations (X′10) | (1) Experiencing unique ice and snow facility /5; (2) experiencing logging in snowfield/3; (3) camping in snowfield/1; (4) creating ice and snow artwork/1 | 10 |

| Variable | Willingness | Dispersion Coefficient of Willingness | Correlation Coefficient with E | OLS Regression Analysis Result Taking W1 as the Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Std. Err. | T Value | VIF | ||||

| X1 | 5.778 | 0.494 | 0.097 ** | 0.127 *** | 0.023 | 5.49 | 1.63 |

| X2 | 5.686 | 0.498 | 0.072 | 0.083 *** | 0.022 | 3.85 | 1.39 |

| X3 | 5.124 | 0.557 | 0.089 ** | 0.117 *** | 0.021 | 5.57 | 1.34 |

| X4 | 5.458 | 0.510 | 0.142 *** | 0.078 ** | 0.023 | 3.31 | 1.58 |

| X5 | 5.923 | 0.477 | 0.073 * | 0.144 *** | 0.022 | 6.64 | 1.41 |

| X6 | 5.141 | 0.545 | 0.080 * | 0.121 *** | 0.022 | 5.62 | 1.36 |

| X7 | 4.809 | 0.578 | 0.073 | 0.056 * | 0.023 | 2.40 | 1.56 |

| X8 | 6.175 | 0.459 | 0.132 *** | 0.148 *** | 0.023 | 6.39 | 1.61 |

| X9 | 6.159 | 0.476 | 0.059 | 0.183 *** | 0.023 | 7.97 | 1.69 |

| X10 | 4.528 | 0.583 | 0.091 ** | 0.037 | 0.023 | 1.63 | 1.36 |

| Constant | - | - | - | 0.340 * | 0.166 | 2.05 | - |

| Tourism Activities | Ranking Supply | Ranking Market Willingness | Ranking Consistency Degree | Adjustment Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X′1 | 1 | 4 | 0.667 | ↓ |

| X′2 | 2 | 5 | 0.667 | ↓ |

| X′3 | 3 | 8 | 0.444 | ↓ |

| X′4 | 4 | 6 | 0.778 | ↓ |

| X′5 | 5 | 3 | 0.778 | ↑ |

| X′6 | 6 | 7 | 0.889 | ↓ |

| X′7 | 7 | 9 | 0.778 | ↓ |

| X′8 | 8 | 1 | 0.222 | ↑ |

| X′9 | 9 | 2 | 0.222 | ↑ |

| X′10 | 10 | 10 | 1.000 | → |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, K.; Tian, X.; Xia, J.; Ou, M.; Tang, C. The Market Responses of Ice and Snow Destinations to Southerners’ Tourism Willingness: A Case Study from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813759

Sun K, Tian X, Xia J, Ou M, Tang C. The Market Responses of Ice and Snow Destinations to Southerners’ Tourism Willingness: A Case Study from China. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813759

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kun, Xiaoli Tian, Jing Xia, Mian Ou, and Chengcai Tang. 2023. "The Market Responses of Ice and Snow Destinations to Southerners’ Tourism Willingness: A Case Study from China" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813759

APA StyleSun, K., Tian, X., Xia, J., Ou, M., & Tang, C. (2023). The Market Responses of Ice and Snow Destinations to Southerners’ Tourism Willingness: A Case Study from China. Sustainability, 15(18), 13759. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813759