Policy Perspective on Governmental Implicit Debt Risks of Urban Rail Transit PPP Projects in China: A Grounded Theory Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Risk Identification of PPP Projects

2.2. Government Debt Risk of PPP Project

2.3. Research Gap

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Study Procedure

3.2. Data Sources

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Wong, Z.; Chen, A.; Shen, C.; Wu, D. Fiscal policy and the development of green transportation infrastructure: The case of China’s high-speed railways. Econ. Change Restruct. 2022, 55, 2179–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Urban Rail Transit Association. 2022 Statistical and Analysis Report on Urban Rail Transit; China Urban Rail Transit Association: Beijing, China, 2023; pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, L. Public–private partnership as a driver of sustainable development: Toward a conceptual framework of sustainability-oriented PPP. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Liu, F.F.; Li, H.Y. Public–private partnership governance mechanism analysis using grounded theory. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Munic. Eng. 2021, 174, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. A holistic review of research studies on financial risk management in public–private partnership projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2549–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F.; Tatari, O.; Alghamdi, L. Enhancing the decision-making process for public-private partnerships infrastructure projects: A socio-economic system dynamic approach. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 69, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Shi, W.X.; Wang, J.C.; Zhou, H.S. A deep learning-based approach to constructing a domain sentiment lexicon: A case study in financial distress prediction. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.T.; Wang, D.D.; Cheng, S.Y. The impact of high speed railway on urban service industry agglomeration. J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 43, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Slavtchev, V. Determinants of the efficiency of regional innovation systems. Reg. Stud. 2011, 45, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfeldt, G.M.; Feddersen, A. From periphery to core: Measuring agglomeration effects using high-speed rail. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 355–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, C.; Qin, C. No difference in the effect of high-speed rail on regional economic growth based on match effect perspective? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 106, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Li, Y. High-speed rails and city economic growth in China. J. Financ. Res. 2017, 11, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.F.; Ni, P.F. Economic growth spillover and spatial optimization of high-speed railway. China Ind. Econ. 2016, 2, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.Z.; Yu, D.H.; Sun, Y.Y. A study on the effects of high-speed railway on the pattern of urban population distribution. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2018, 5, 94–108+128. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Jia, P.; Yuan, Q. Economic effect of high-speed rail: Empirical analysis of Shin-kansen’s impact on industrial location. J. Transp. Eng. 2012, 138, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.R.; Fan, Y.; Xia, Y. The environmental impact and economic assessment of Chinese high speed rail investments. China Popul. Environ. 2017, 27, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nayyer, M.I.; Aravindan Mukkai, R.; Thillai Rajan, A. Effect of transparency on the development phase of Public-private Partnership: Analysis of highway projects. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 052019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosycarz, E.A.; Nowakowska, B.A.; Mikolajczyk, M.M. Evaluating opportunities for successful public–private partnership in the healthcare sector in Poland. J. Public Health 2019, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Criticality analysis of financial risks of public-private partnership projects in a Sub-Saharan African country. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 052026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubair, S.; Singh, J. Critical success factors of Public-private Partnership (PPP) projects in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Webology 2022, 19, 1521–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amovic, G.; Maksimovic, R.; Bunci, S. Critical success factors for sustainable Public-Private Partnership (PPP) in transition conditions: An empirical study in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Z.; Johar, F. Critical success factors of public–private partnership projects: A comparative analysis of the housing sector between Malaysia and Nigeria. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, G.A.; Painting, N. Critical success factors for public private partnership in the Afghanistan construction industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering, Project, and Product Management, Taipei, China, 4–6 November 2016; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.H.; Adnan, H.; Baharuddin, H.E.A.; Bakhary, N.; Rashid, Z.A. Financial risk in managing Public-Private Partnership (PPP) project. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2022, 1067, 012074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhshian, A.; Re Cecconi, F. Data-driven process mining framework for risk management in construction projects. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2022, 1101, 032023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.F.; Wang, X.Y.; Ye, P.H.; Jiang, L.P.; Feng, R.X. Safety accident analysis of power transmission and substation projects based on association rule mining. Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.T.; Cheng, M. An Evolutionary Game Analysis of Supervision Behavior in Public–private Partnership Projects: Insights from Prospect Theory and Mental Accounting. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1023945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.H.; Wu, S.L. Review of studies on risk early warning of Public–Private Partnership projects in characteristic town. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2019, 330, 022105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, N.; Shahzad, W.; Khalfan, M.; Rotimi, J. Risk identification, assessment, and allocation in PPP projects: A systematic review. Buildings 2022, 12, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhat, N.M.; Dung, L.A. Optimizing investment sSelection for PPP framework in the transport sector: A risk perspective. Civil Eng. Arch. 2021, 9, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Che, M.; Duan, Y.Y.; Li, S.J.; Chen, Y. Research on risk identification and countermeasures of water resources survey and design enterprises participating in PPP projects. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. R. 2020, 5, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.H.; Ali, T.H.; Hassan, S.; Zainun, N.Y.; Javed, Y.; Memon, S.A. Risk severity matrix for sustainable Public–Private Partnership projects in developing countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.F.; Xu, W.; Xia, B.; Skibniewski, M.J. Exploring key indicators of residual value risks in China’s public–private partnership projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04017046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Hanaoka, S.; Shuai, B. Modeling optimal thresholds for minimum traffic guarantee in public–private partnership (PPP) highway projects. Eng. Econ. 2022, 67, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shrestha, A.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G. Government guarantee decisions in PPP wastewater treatment expansion projects. Water 2020, 12, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R. Effects of public supports for mitigating revenue risk in public–private partnership projects: Model to choose among support alternatives. J. Constr. Eng. Manag 2021, 147, 4021167.1–4021167.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manish, K.S.; Marta, G.P.; Simón, S.R. Increasing Contingent Guarantees: The Asymmetrical Effect on Sovereign Risk of Different Government Interventions; IREA Working Papers 201914; University of Barcelona, Research Institute of Applied Economics: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kudelich, M.I. Financial Participation of Public Partners in Public–Private Partnership. Financ. J. 2020, 6, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, B.; Frederic, M.; Phuong, T. Public–private partnerships from budget constraints: Looking for debt hiding? Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2017, 51, 56–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzakova, S.; Nurlanov, A. Public–private partnership in gaining sustainable development goals in Kazakhstan. Cent. Asian Econ. Rev. 2021, 2, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. Review of the research on the fiscal risk of PPP model of municipal infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Economic Management and Cultural Industry, Shenzhen, China, 15–17 November 2019; pp. 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio, A.; Zenios, S.A. Contingent convertible bonds for sovereign debt risk management. J. Glob. Dev. 2018, 9, 20170011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duan, X.; Zhang, Z.S.; Zhang, W. How is the risk of major sudden infectious epidemic transmitted? A grounded theory analysis based on COVID-19 in China. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 795481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hosseini, Z.; Ebadi, A.; Aghamolaei, T.; Nedjat, S. A model for explaining adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV/AIDS: A grounded theory study. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2022, 30, e5735–e5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, J.; Vries, R.A.J.; Lemke, M. The three-step persuasion model on YouTube: A grounded theory study on persuasion in the protein supplements industry. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 838377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Huang, Y.T. Intersecting self-stigma among young Chinese men who have sex with men living with HIV/AIDS: A grounded theory study. Ameri. J. Orthopsychiatry 2022, 93, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gram, L.; Paradkar, S.; Osrin, D.; Daruwalla, N.; Cislaghi, B. ‘Our courage has grown’: A grounded theory study of enablers and barriers to community action to address violence against women in urban India. BMJ Global Health 2022, 3, e011304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebli, P.; McBryde-Redzovic, A.; Al-Amin, N.; Gutierrez-Kapheim, M.; Molina, Y.; Mitchell, U.A. Understanding COVID-19 risk perceptions and precautionary behaviors in black chicagoans: A grounded theory approach. Health Educ. Behav. 2023, 50, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifian, M.; Raheb, G.; Uddin, R.; Abdi, K.; Alikhani, R. The process of stigma experience in the families of people living with bipolar disorder: A grounded theory study. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurs. Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.N.; Xia, L.X.; Wang, W.W.; Li, Y.Q.; Liang, Y. Left-behind children’s positive and negative social adjustment: A qualitative study in China. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P. Review of studies on the critical success factors for public–private partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Project. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, O.M.; Geddes, R.R.; Do, W.; Gao, H.O.; Beheshtian, A. Revenue-risk-sharing approaches for public–private partnership provision of highway facilities. Stud. Transp. Policy 2018, 6, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; Cui, X.D.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.C. Impact of Government Subsidies on The Innovation Performance of The Photovoltaic Industry: Based on The Moderating Effect of Carbon Trading Prices. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, N.; Pellegrino, R. Revenue guarantee in public private partnerships: A win–win model. Construct. Manag. Econ. 2018, 36, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Hao, S.; Li, X. Relationship orientation, justice perception, and opportunistic behavior in PPP projects: An empirical study from china. Front. Psychol. 2021, 1, 635447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Data |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 86.71% |

| 2021 | 85.79% |

| 2022 | 87.63% |

| No | Themes | Original Statements |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compensation for operating costs | A1: More than 60% of the operating costs require subsidies from the Hohhot Municipal Government. |

| A2: The operating costs of enterprises are subsidized by the government. | ||

| A3: Based on the full cost of the subway, an annual financial subsidy of 800 to 900 million yuan is required. | ||

| A4: In terms of the return mechanism, the project adopts a feasibility gap subsidy model, where the income source of the project company is “user payment and government subsidies”. | ||

| A5: The project company realizes the repayment of project company B’s debts, the recovery of investment by party C, and obtains reasonable investment returns through operating ticket revenue, resource development revenue, and government subsidies, | ||

| A6: Considering the feasibility gap subsidy project, the government’s equity investment will be partially waived for dividends, and the equity investment will be recovered from the project company. The initial subsidy funds will be reduced. | ||

| 2 | Payment for performance | A7: If the specified assessment indicators are met, the municipal government (or authorized unit) shall pay the project company’s operating service fee in full. If it fails to meet the specified assessment indicators, it shall be deducted from the payable operation service fee. |

| 3 | Minimum-Proceeds-Guarantee | A8: The government provides necessary subsidies for the project based on project investment, financing, and operational efficiency, taking into account the reasonable returns of social investors. |

| A9: The subsidy is provided by the government to social investors when the project’s income cannot meet the reasonable return rate of social investors. | ||

| A10: The financial department pays the difference between the agreed fare and the clear fare to the Hangzhou and Hong Kong metro through the government purchase of services. | ||

| A11: When there is a feasibility gap in the cash flow statement of the project financial plan under normal operation of the project, the Fuzhou Municipal Government (or through implementing agencies) shall provide government subsidies to the project company by the provisions of the franchise agreement. | ||

| A12: In Sanya, the tram adopts a one-ticket system of 3 yuan per person per time, which is super cheap and lower than many subway fares in China. | ||

| A13: If the actual ticket price is lower than the calculated ticket price, the government will compensate the franchise company for the difference. | ||

| 4 | Compensation for loss of passenger flow | A14: The minimum demand risk shall be undertaken by Party A. |

| A15: If the actual passenger flow of that year is less than 90% of the predicted passenger flow, the B project company, in conjunction with Party B, shall report to Party A for approval and make up for it separately through financial subsidies. | ||

| 5 | Investment compensation due to design changes | A16: Any changes of investment caused by design changes that are approved by the municipal government (such as changes in construction scale, adjustments to station locations, and major changes in main and ancillary projects) shall be compensated by the municipal government. |

| 6 | Cost compensation due to legal or policy changes | A17: When the construction or operating costs of the project company increase due to requirements from the municipal government or changes in laws at the municipal government level, reasonable compensation shall be given to the project company. |

| A18: Actively utilizing administrative means to mitigate the impact of policy and legal adjustments. | ||

| 7 | Undertaking changes of objective factors | A19: Any changes in ticket prices caused by objective factors shall be undertaken by the government. |

| A20: The risk of passenger flow, price rise, ticket price, force majeure, etc. shall be jointly undertaken by Party C and Party A through the establishment of risk sharing through PPP contracts. | ||

| 8 | Demolition work | A21: Except for the “two sites and one section” project, the external power supply system and 110kV main substation project, as well as the installation of related mechanical and electrical equipment, the relevant land acquisition and demolition work shall be handled by the district and county governments along the project, and the funds shall be provided by the district and county governments along the line. |

| 9 | Land support | A22: The first party shall allocate 2000 acres of land resources for this project and authorize the second party to carry out primary land development. The value-added income from the primary land development shall be used as the source of funding for the project financing repayment of principal and interest. |

| 10 | Price discount for minor enterprises | A23: According to the Interim Measures for Promoting the Development of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises through Government Procurement issued by the Ministry of Finance, a 6% deduction will be given for the prices of small and micro-enterprise products in this project. |

| 11 | Guaranteed subsidy time | A24: The first party grants the project company franchise rights, and the franchise rights owned by the project company will not change due to changes in shareholders. |

| A25: After the signing of this contract, Party A shall provide Party C with an approved medium-term financial plan that includes the financial feasibility gap subsidy for this project (if the planning period cannot cover the cooperation period of this project, Party A shall provide it in a rolling manner). | ||

| 12 | Project takeover | A26: If Party C or the project company seriously violates the provisions of the cooperation contract, affects the continuous stable and safe supply of public goods and services, or endangers national security and major public interests, the municipal government has the right to temporarily take over the cooperation project until the cooperation project is initiated and terminated in advance. |

| 13 | Concession financing | A27: Debt financing is through a pledge of franchise rights, project asset mortgage, and other means. |

| A28: PPP financing is a project-based financing activity and a form of project financing, mainly based on the expected returns, assets, and the strength of government support measures of the project. | ||

| A29: The direct benefits of project operation and the benefits converted through government support are the sources of funds for repaying loans. The assets of the project company and the limited commitments given by the government are the safety guarantees of the loans. | ||

| A30: Social capital and the government jointly establish a project company with a shareholding ratio of 70% and 30%. | ||

| A31: The Municipal Public Transport Group, as a representative of the government investor, contributed 100 million yuan, accounting for 27.22% of the project company. | ||

| 14 | Relationship coordination among all parties involved | A32: The phenomenon of low participation rate of social capital, low willingness to participate, and high failure rate in PPP projects in China has emerged. Therefore, the government should actively cultivate relationships among all parties involved in PPP. |

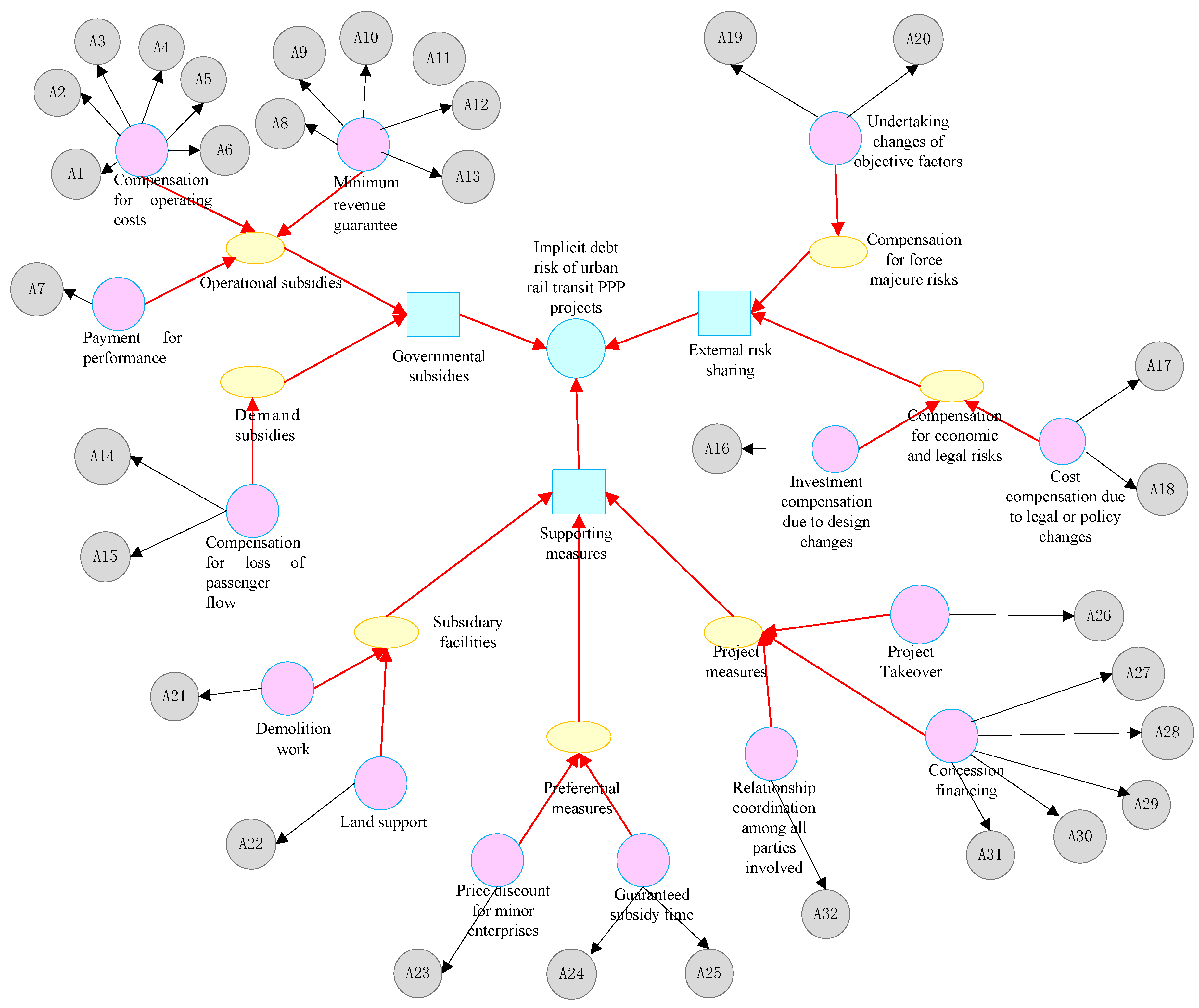

| Main Category | Subcategory | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Governmental subsidies | Operational subsidies | Compensation for operating costs |

| Payment for performance | ||

| Minimum revenue guarantee | ||

| Demand subsidies | Compensation for loss of passenger flow | |

| External risk sharing | Compensation for economic and legal risks | Investment compensation due to design changes |

| Cost compensation due to legal or policy changes | ||

| Compensation for force majeure risks | Undertaking changes of objective factors | |

| Supporting measures | Subsidiary facilities | Demolition work |

| Land support | ||

| Preferential measures | Price discount for minor enterprises | |

| Guaranteed subsidy time | ||

| Project measures | Project Takeover | |

| Concession financing | ||

| Relationship coordination among all parties involved |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Yuan, J. Policy Perspective on Governmental Implicit Debt Risks of Urban Rail Transit PPP Projects in China: A Grounded Theory Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914078

Zhang Y, Jin W, Yuan J. Policy Perspective on Governmental Implicit Debt Risks of Urban Rail Transit PPP Projects in China: A Grounded Theory Approach. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914078

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yajing, Weijian Jin, and Jingfeng Yuan. 2023. "Policy Perspective on Governmental Implicit Debt Risks of Urban Rail Transit PPP Projects in China: A Grounded Theory Approach" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914078

APA StyleZhang, Y., Jin, W., & Yuan, J. (2023). Policy Perspective on Governmental Implicit Debt Risks of Urban Rail Transit PPP Projects in China: A Grounded Theory Approach. Sustainability, 15(19), 14078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914078