1. Introduction

The number of tourists has risen sharply with the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and a gradual recovery of the global economy. The resurgence of tourism and its growing carbon footprint has brought renewed attention to the impact of the tourism industry on climate change [

1,

2]. Statistics (

https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Ten_Principles_for_Sustainable_Destinations_2022.pdf, accessed on 30 July 2023) show that tourism contributed about 8% of the global greenhouse gas emissions in 2021. This makes more tourism enterprises want to use clean energy, green materials, and green technologies, and to implement carbon neutral and carbon offsetting technologies to eliminate the impact of their carbon footprints [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Some existing studies have indicated that in response to the national dual-carbon strategy and the requirements for sustainable tourism development, investment in carbon emission reduction activities can help theme parks cope with environment-related risks, reduce property operating costs, and lead to asset appreciation [

7,

8].

Tourists’ consumption attitudes have changed in recent years due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the global economic downturn; people are more careful with their money and personalized travel has become mainstream. A theme park is a commercially operated enterprise that offers rides, shows, merchandise, food services, and other forms of entertainment in a themed environment [

9]. Because of its distinctive theme concept, unique sightseeing, and amusement environment, the theme park industry can fully meet the personalized tourism needs of visitors [

10,

11,

12]. Statistics (

https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1750267574438094487&wfr=spider&for=pc, accessed on 22 April 2023) show that the total number of visitors to 70 theme parks in China reached about 75 million in 2021. The market size of China’s theme park industry was about 30 billion RMB from 2020 to 2022, which represents only half of the peak market size in 2019 (

https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1749259796291381713&wfr=spider&for=pc, accessed on 22 April 2023). In many international theme parks, 30% of the revenue comes from admission fees, 30% from retail, and 40% from food and accommodation. While admission fees are not the biggest source of revenue, visitors’ perceptions of admission fees largely determine whether they visit a theme park. A theme park ticket is a consumption contract between visitors and theme parks [

13], thus visitors tend to associate the admission fee they pay with the touring experience they get from theme parks [

14,

15,

16]. They expect the price they pay for their tickets to be commensurate with the quality of the service they receive. If visitors do not get the quality of service or touring experience they expect, they will question the ticket pricing strategy or the operational management level of theme parks, which will affect their willingness to revisit the theme parks and their willingness to spend extra money in theme parks [

11,

17,

18]. In this case, the theme parks’ revenues will be greatly reduced and their sources of investments in clean energy and green technologies will be greatly affected. Therefore, in the context of a low-carbon tourism economy, the reasonable design of theme parks’ admission fees helps improve their revenue management (RM) ability and sustainable development ability. Once theme parks have sustainable funds, they can invest in low-carbon activities within the parks, including using clean energy and green technologies, renovating energy-efficient buildings, and improving the ecological environments of scenic spots.

RM refers to selling perishable services to the most profitable mix of customers to maximize revenue [

19,

20,

21]. Similar to other industries that apply RM, the theme park industry has perishable capacity, high fixed and low variable costs, variable demand, and segmental markets [

22]. In reality, most theme parks adopt various RM techniques based on visitors’ diverse characteristics, needs, or the status quo of the tourism market [

11]. Discriminatory pricing strategy is one of the commonly used RM techniques [

16,

23]. Theme parks set different admission fees based on the payment ability and willingness of different visitors, so that all types of visitors can afford and are willing to pay the ticket price. In practice, there are many examples where discriminatory pricing strategies are applied in theme parks. For example, Shanghai Disneyland charges adults 719 yuan for one-day admission, while children, seniors, and people with disabilities are charged 539 yuan. Visitors can buy Shanghai Disneyland tickets at 672 yuan for adults and 500 yuan for children through TikTok. Shenyang Fangte Happy World charges 280 yuan for visitors arriving during the daytime and 199 yuan for visitors entering at night.

The purpose of implementing discriminatory pricing strategies for theme parks is to get visitor surplus in different market segments to increase the theme park’s revenue. In reality, visitors to the same theme park are charged different admission fees. Based on the equity theory [

23,

24,

25], the visitors who get a discount on the admission fee are called advantaged visitors, and the visitors who buy tickets at the full price are called disadvantaged visitors; both are called visitors with unequal status [

26]. From the visitor’s viewpoint, the admission fee is a proxy for service quality [

27]. If the admission fees for theme parks are set too high or the discriminatory basis of the pricing strategy is unreasonable, the visitors’ service value perception will be low and they will perceive the price to be unfair, which will further lead to a decline in the number of visitors and a decline in the theme park’s revenue. From the viewpoint of sustainability and revenue maximization, the price fairness perception (PFP) and service value perception (SVP) of visitors can influence theme parks’ market demand and the achievement of revenue targets, which are key guarantees for theme parks to secure sustainable funds for investing in clean energy, green technologies, and other low-carbon activities [

28]. Therefore, theme parks should focus on the PFP and SVP of visitors with unequal status [

16].

Many scholars have studied the application of RM in theme parks [

11,

16,

22,

23,

29,

30]. The majority of existing studies have focused on exploring the factors that impact visitors’ satisfaction and theme parks’ revenues, such as the layout of recreation facilities, the number of themes, the types of rides, and waiting times. However, how to achieve an established revenue target and how to address visitors’ social welfare under the discriminatory pricing scheme have not been elucidated. In particular, with regard to where discrimination exists in the pricing strategies, studies have not differentiated the utilities of visitors with unequal status. To fill the above research gaps, this study aims to investigate the role of discriminatory pricing strategy in supporting sustainable tourism in theme parks. To solve this scientific problem, the following research questions are worth studying:

How can theme parks achieve an established revenue target from the perspective of sustainability and revenue maximization?

How can theme parks achieve distributed justice between their revenue and visitors’ social welfare in the long run?

How can theme parks formulate the utility functions of visitors based on PFP and SVP, and how can theme parks achieve distributed justice between visitors with unequal status?

In this study, the first research question is aimed at ensuring that theme parks secure stable revenue from admission fees and in-park consumption so that they have sufficient money for investment in low-carbon activities, including clean energy and green technologies. The second and third research questions are aimed at ensuring that theme parks maintain a sustainable relationship with their visitors and enhance the satisfaction and brand loyalty of visitors with unequal status.

This study is organized as follows. Related studies are presented in

Section 2. In

Section 3, the discriminatory pricing model is proposed based on equity theory, transaction utility theory, and the goal programming method, and a numerical example is introduced. In

Section 4, some sensitivity analysis experiments are conducted based on factors such as the theme park’s established revenue target, the service homogeneity coefficient, and visitors’ average WTP. Some valuable managerial insights based on the sensitivity analysis results are discussed in

Section 5. Finally, the conclusions, limitations, and future work are presented in

Section 6.

3. Models

3.1. Problem Description

In response to the national dual carbon strategy and the requirements for sustainable development in the tourism industry, a discriminatory pricing strategy aimed at ensuring sustained investment in low-carbon activities is proposed in this study. Theme parks charge discriminatory admission fees for different visitors. In this section, based on the transaction utility theory [

45] and the equity theory [

24], the PFP and SVP of the interrelationship between visitors’ touring experience and the admission fees paid to theme parks are investigated. The main factors that influence visitors’ PFP and SVP such as unequal status, reference price, and similarity in visitors’ touring experiences are considered. Regarding the discriminatory pricing strategies used by theme parks, visitors with unequal status can access the open information on the admission fee scheme. They may compare similarities in their experiences (namely, the admission fee paid and the touring services received). If visitors are satisfied with the comparative results, price fairness and high service value will be perceived; otherwise, price unfairness and low service value will be induced, probably along with negative reactions. According to previous studies [

38,

40,

43], the number of attractions visited and the expected waiting times are important criteria for measuring visitors’ satisfaction with theme parks. In this study, these criteria are used to describe the experience similarity between advantaged and disadvantaged visitors. For example, some theme parks provide visitors with hedonic and exciting facilities. Adults can access most facilities in such theme parks, although they need to pay the full ticket price. On the contrary, children and the elderly can only access some of the hedonic facilities due to their physical conditions, hence they are offered discounted fares. Real-world examples demonstrate the feasibility of exploring the experience similarity between visitors with unequal status based on the number of attractions visited and the different admission fees paid. These examples also justify the necessity and importance of incorporating experience similarity in the study of discriminatory pricing strategies. Thus, in this study, the visitors’ experience similarity is considered a key factor in describing the utility functions of visitors with unequal status.

Therefore, when formulating their discriminatory price strategies, theme parks need to consider the experience similarities or differences between the utility of visitors who get ticket discounts (the advantaged visitors) and that of visitors who do not get ticket discounts (the disadvantaged visitors). This is because the differences in utilities or the similarities in experiences will affect the satisfaction and brand loyalty of the visitors [

29,

46] as well as their willingness to consume within the theme park [

23]. Under these circumstances, experience similarity is used to evaluate the PFP, SVP, and utilities of visitors with unequal status.

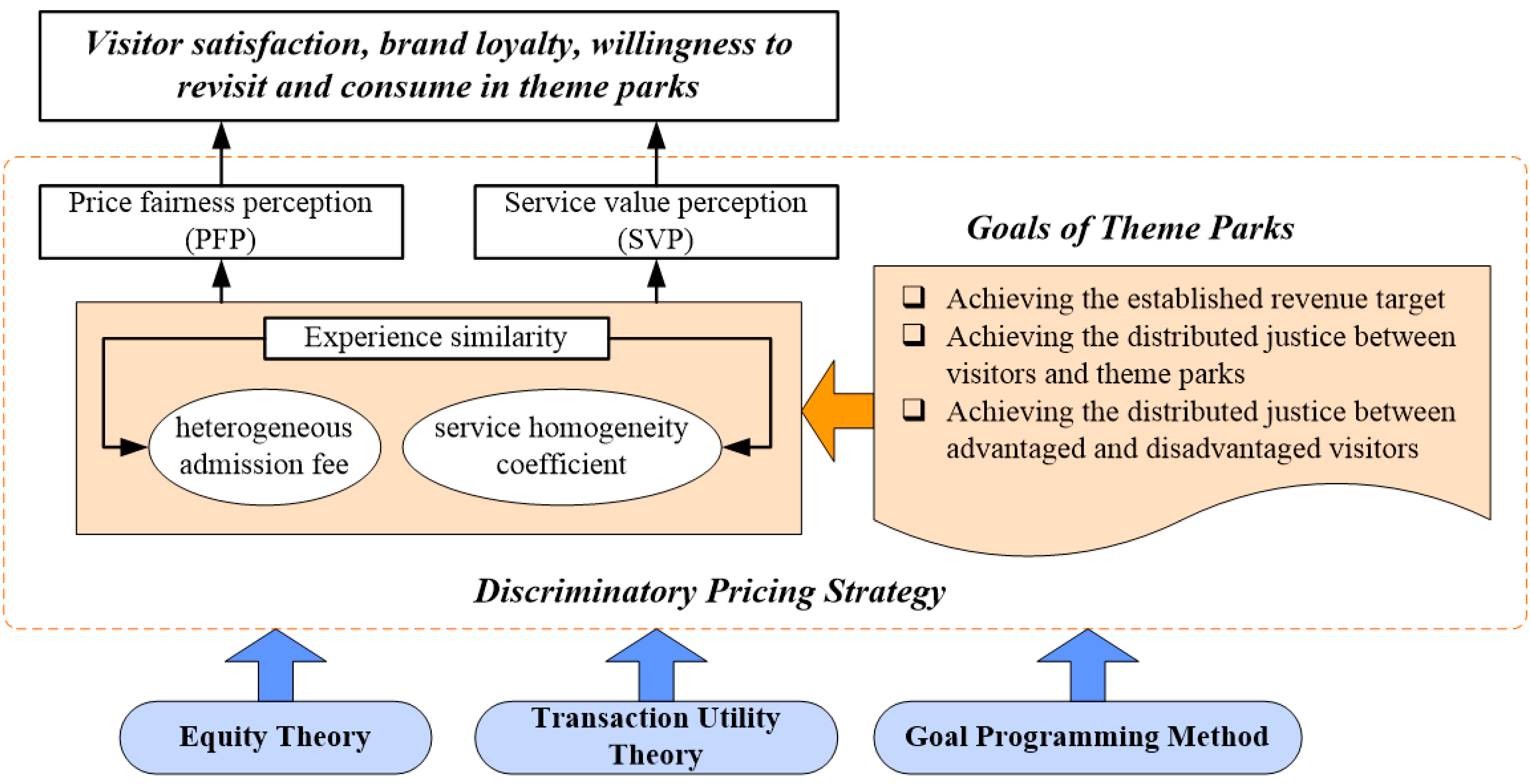

In this section, individual utility functions of visitors with unequal status are first established based on the equality theory and the transaction utility theory, taking into account the PFP and SVP of visitors. Second, the revenue function of the theme park and the utility function of all visitors are constructed. Finally, in accordance with the proposed research questions and based on the goal programming method, a multi-goal programming-based discriminatory pricing model is proposed, taking into account the following three goals: achieving the established revenue target, achieving distributed justice between theme parks and their visitors, and achieving distributed justice between advantaged visitors and disadvantaged visitors. The research framework is shown in

Figure 1.

To facilitate modeling, the parameters and symbols used in this study are introduced as follows (

Table 1).

3.2. Research Assumptions

Before establishing the model, the following research assumptions are introduced based on the existing literature and real-world practices in the theme park industry.

First, visitors to the theme park are divided into two groups: advantaged visitors and disadvantaged visitors; their admission fees satisfy . The total utility of visitors to the theme park is the sum of the utilities of advantaged and disadvantaged visitors, i.e., . The total visitor demand of the theme park is the sum of the number of advantaged and disadvantaged visitors, i.e., . The WTP of the advantaged and disadvantaged visitors to the theme park satisfies the same uniform distribution, i.e., . The market demand for the advantaged visitors and the disadvantaged visitors is assumed to follow a similar linear function, i.e., .

Second, the parameter denotes the service homogeneity coefficient. The parameter means that the services offered to the advantaged and disadvantaged visitors are different. For example, if all attractions in a theme park can only be accessed by visitors over 11 years old and under 65 years old, then visitors under the age of 11 or over the age of 65 will have completely different service experiences from those aged 11–65. Conversely, the parameter means that the services offered to the advantaged and disadvantaged visitors are identical. For example, a theme park provides the same service and the same standard of service to visitors who buy tickets online and those who buy tickets on-site.

Third, from a sustainability point of view, if visitors feel that the service they experienced is not worth the price they paid, then they will think that the ticket price is unfair and the quality of service is low. In the long run, the repeat-visit rate and willingness to consume in the theme park will reduce. Therefore, when the theme park is developing a discriminatory pricing strategy, they need to balance the theme park’s revenues and the utility of visitors and realize distributed justice between them (namely, the second goal in the goal programming model) to reduce the negative impact of the decline in visitor satisfaction.

Finally, different visitors are charged different admission fees, leading to visitors’ perceived price unfairness due to price comparisons. When formulating discriminatory pricing strategies, the theme park needs to balance the utility of advantaged visitors against that of disadvantaged visitors and realize distributed justice between them (namely, the third goal in the goal programming model). In this way, although the disadvantaged visitors pay more than the advantaged visitors in terms of admission fees, they will not perceive the system to be more unfair and will therefore not feel dissatisfied.

3.3. Model Setup

The utility of consumers, as described by Thaler [

35], Lichtenstein et al. [

45], and Bei and Simpson [

47], is presented in Equation (1).

As shown in Equation (1), acquisition utility is positively influenced by the benefits that people believe they are getting from acquiring and using the commodity, but is negatively influenced by the money given up for it. Received quality represents one’s estimation of a commodity’s cumulative excellence [

48]. Transaction utility means that people would like to assess the merits or value of a deal by comparing the selling price with their internal reference price [

35,

49]. It reflects the satisfaction or pleasure people gain from taking advantage of the financial terms of the deal [

35,

45,

49,

50].

In the theme park tourism context, and based on findings of previous empirical studies [

23,

25,

26], service homogeneity coefficient, admission fees, price difference, visitors’ unequal status, and reference price are used to represent theme park visitor utility. According to Equation (1), the visitors’ acquisition utility reflects the economic gain or loss from purchasing the theme park ticket. It depends on the reserved price and the value of service quality received compared with the cost. For the advantaged visitor, the psychological benefit is a positive feeling about purchasing the limited service at a discounted price; his received quality depends on the estimated value of the limited service. According to Wang et al. [

23], Wu et al. [

26], and real-world practices, the reference price for the advantaged visitor is the full price or the price the disadvantaged visitor is charged. For the disadvantaged visitor, the psychological benefit is a positive feeling about purchasing the full service at a full price; his received quality depends on the estimated value of the full service. The reference price for the disadvantaged visitor is the reserved theme park admission fee. The utility functions for advantaged and disadvantaged visitors are given in Equations (2) and (3), respectively.

Accordingly, the average utilities for advantaged and disadvantaged visitors are given in Equations (4) and (5), respectively.

The total utility for all visitors with unequal status and the theme park’s revenue are given in Equations (6) and (7), respectively.

Based on the descriptions of visitor utility and theme park revenue, the discriminatory pricing model for the theme park is given by the following goal programming model:

It should be noted that the goal programming method is a mathematical programming method used in decision analysis [

51]. In management practice, there are always conflicting goals that may not be achieved due to limited resources or various other reasons. In the goal programming method, these constraints are regarded as “goals”. The overall optimization objective is to give an optimal result that is as close to the specified value as possible. Priorities classify goals by importance and weigh the different goals in a certain order of priority.

A field study was conducted in Shenyang Fangte Happy World in 2018–2019, including in-depth interviews with the management and random interviews with visitors. In terms of the park’s investment in clean energy and green technologies, the interview results showed that tickets and in-park consumption were the main sources of funds for low-carbon investments in the park. In terms of the factors affecting the satisfaction of theme park visitors, the interview results showed that ticket discounts offered to different groups of visitors, the touring experience, and comparison with other visitors’ touring experiences significantly affected visitors’ willingness to revisit and consume. Based on these interview results, in the context of discriminatory pricing strategies for sustainable tourism in theme parks, three goals are considered in the goal programming model, as shown in Equations (8) and (9). The first goal (P1) is to maximize the theme park’s revenue and a minimum established revenue target must be met. The second goal (P2) is to balance the theme park’s total revenue and the visitors’ total utility, which is in line with the equity theory and the distributed justice principle. The third goal (P3) is to balance the average utilities of advantaged visitors and disadvantaged visitors, which is also in line with the equality theory and the distributed justice principle. Moreover, and are positive and negative deviation variables of Pi. Since the first goal is revenue-oriented, the negative deviation variable should be as small as possible. For the second and third goals, and should be as close as possible, allowing or to be appropriately greater (or less) than or , respectively. Thus, and should be as small as possible.

These three goals fully reflect the long-term concerns of the theme park from the perspectives of sustainability and revenue maximization. Achieving the first goal allows the theme park to have sufficient and sustained funds to invest in clean energy and green technologies and to maintain the sustainable development of theme park tourism. Achieving the second and third goals can enhance visitors’ satisfaction, brand loyalty, and willingness to revisit and consume in the theme park in the long run, which is conducive to better realization of the first goal. The order of priority of these three goals is

, which indicates that the first goal is the most important, the second goal is less important than the first goal, and the third goal comes last. The setting of these three goals and the model’s solution help solve the three research questions proposed in

Section 1.

3.4. Numerical Study

Based on interviews from the field study in Shenyang Fangte Happy World in 2018–2019, a numerical study is conducted to justify the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed model. Based on historical data and interviews with managers, the demand for this theme park is approximately represented as a linear function of its admission fee, i.e.,

. Based on random interviews with visitors to this theme park, the WTP for theme park admission fees is supposed to follow a uniform distribution U [80, 280]. Based on interviews with the management, the theme park would like to achieve at least 8 × 10

6 RMB in revenue per quarter during the peak seasons. There are about 20 attractions or rides in this theme park, 6 of which are not suitable for visitors over 65 years old or visitors suffering from heart disease and high blood pressure. This means that the service homogeneity coefficient enjoyed by such visitors is

. Thus, Equation (9) can be rewritten as Equation (10).

We used the LINGO 11.0 software to run the model and obtained the following results: the admission fee for advantaged visitors = 125 RMB and the admission fee for disadvantaged visitors = 212 RMB.

5. Practical Implications

The purpose of the proposed goal-programming-based discriminatory pricing model is to increase revenue and visitor satisfaction. In the low-carbon tourism economy, theme parks’ investments in clean energy and green technologies mainly come from ticket revenue and visitors’ in-park consumption. Existing research justifies that visitors’ PFP toward the theme park’s pricing strategy and the SVP toward the theme park’s touring experience could greatly affect the theme park’s revenues and visitor satisfaction [

22,

23,

26,

51]. Some suggestions and managerial implications for theme park management are summarized based on the sensitivity analysis results from the viewpoint of sustainability and revenue maximization.

Regarding the formulation of discriminatory pricing strategies, managers first need to consider the impact of the established revenue targets on the pricing strategy. If the expected revenue target is set too high, the theme park needs to raise the admission fees for disadvantaged visitors and keep discount admission fees for advantaged visitors at a more stable level. However, doing so might, to a certain extent, damage the perceptions of price fairness and service value among the disadvantaged visitors, thus the theme park needs to focus on improving service quality in the park, for example, by displaying the waiting time for each attraction and increasing the number of amusement facilities. Second, managers need to consider the impact of service heterogeneity on the pricing strategy. When choosing the basis for price discrimination, theme park managers should pay attention to the degree of service heterogeneity provided by theme parks to visitors with unequal status. For example, if the ticket purchase channel is used as the basis for discrimination, the price difference should not be too large due to the small difference in the services experienced by different types of visitors. Otherwise, this will lead to dissatisfaction and unfair perception by disadvantaged visitors (e.g., those who buy tickets on-site) against advantaged visitors (e.g., those who buy tickets online). As another example, if age is used as the basis for discrimination, since children and the elderly experience fewer thrilling attractions or rides compared with adult visitors, the theme park can formulate reasonable price discounts for advantaged visitors based on the degree of service homogeneity or heterogeneity. Finally, managers need to consider the impact of visitors’ WTP on the pricing strategy. Affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the global economic downturn, some non-popular theme parks need to lower their expectations about visitors’ WTP. However, a rebound in the tourism industry could see a spurt in the demand for visiting popular theme parks. In this case, such theme parks can raise their expectations of visitors’ WTP. When the visitors’ WTP to pay for a theme park is generally low, the admission fees for advantaged visitors and disadvantaged visitors charged by the theme park can differ greatly. On the contrary, when visitors’ WTP for a theme park is generally high, the difference in ticket prices formulated by the theme park should be small. The theme park can design different discriminatory pricing strategies by adjusting their expectations of visitors’ WTP to reach the established revenue target and achieve sustainable development of the theme park in the long run.

Regarding increasing theme park revenues, when the service heterogeneity or service homogeneity provided by the theme park to visitors with unequal status is larger, the theme park’s revenue will be higher. On the contrary, when the service heterogeneity or service homogeneity provided by the theme park to visitors with unequal status is of a medium level, the theme park’s revenue will be very low. This means that if the theme park wants to obtain higher revenue, it needs to have a clearer positioning, such as focusing on providing thrilling attractions or rides, focusing on providing attraction facilities for young children or focusing on providing cultural landscape tourism projects. If the theme park’s positioning is not clear, it may cause dissatisfaction among visitors, irrespective of the type. On the other hand, when the visitors’ WTP for the theme park is higher, the market size of the theme park is larger and the revenues are higher. On the contrary, when the visitors’ WTP for the theme park is lower, the market size of the theme park is smaller and the revenue is lower. This means that theme park managers should try their best to improve visitors’ WTP for the theme parks, for example by creating online celebrity attractions, promoting green tourism concepts, and improving the quality of support services inside and outside the parks.

6. Conclusions

This article provides a goal-programming-based discriminatory pricing model for sustainable tourism in theme parks. It is a pioneer in discussing the role of discriminatory pricing strategy in supporting theme parks’ sustained investment in clean energy and green technologies. Similarities in touring experiences are studied based on the transaction utility theory, equity theory, unequal status, price fairness perception, and service value perception of visitors. The proposed goal-programming-based discriminatory pricing model achieved three goals: the theme park’s established revenue target, distributed justice between the theme parks and visitors, and distributed justice between visitors with unequal status. Some conclusions that are based on the research questions proposed in

Section 1 are summarized.

First, from the perspective of sustainability and revenue maximization, the theme park can adopt the proposed discriminatory pricing strategy to achieve the established revenue target (P1 in the goal programming model) and use it as a source of money for investment in clean energy and green technologies. If the revenue target is set too high, the theme park needs to raise the admission fees for disadvantaged visitors. In the meantime, the corresponding quality of service should also be improved.

Second, in the goal programming model, the second goal (P2) is to realize distributed justice between the theme park and visitors. It guarantees that the total revenue of the theme park and the total utility of visitors with unequal status will not deviate too much from each other. The theme park should balance the admission fees charged with the heterogeneous services provided to different visitor groups.

Third, the PFP and SVP of visitors are considered in the visitor utility function. The similarity in visitors’ touring experience (heterogeneous admission fee and service homogeneity coefficient) is used to describe their PFP and SVP. Based on the utility functions of visitors with unequal status, the realization of the third goal (P3) in the goal programming model realizes distributed justice between advantaged visitors and disadvantaged visitors. It guarantees that the average utilities of advantaged visitors and disadvantaged visitors will not deviate too much from each other.

In the context of sustainable tourism in theme parks, the contribution of the proposed discriminatory pricing strategy has two aspects. For one thing, the proposed discriminatory pricing strategy can help the theme park maintain a relatively stable number of visitors—there will not be too many visitors in peak seasons and too few visitors in off-peak seasons. In addition, the proposed discriminatory pricing strategy can ensure that the theme park will achieve the established revenue target and have sufficient funds for low-carbon activities. These achievements play an important role in coordinating the in-park human resources, managing the energy demands of the theme parks, and realizing low-carbon sustainable development and green transformation. For another, the proposed discriminatory pricing strategy can make the theme park value the social welfare of visitors. This strategy realizes distributed justice between advantaged and disadvantaged visitors and distributed justice between visitors and theme parks. In this way, visitors’ satisfaction, brand loyalty, and willingness to revisit and consume within theme parks will be improved in the long run.

From the perspective of sustainability and revenue maximization in theme parks, this study has limitations that provide avenues for future research. The discriminatory pricing strategy proposed in this study is based on three constraints: the established revenue target, distributed justice between the theme park and its visitors, and distributed justice between advantaged and disadvantaged visitors. In reality, many other factors affect discriminatory pricing, including the types of theme parks, the diverse characteristics of different visitor groups, and the cultural backgrounds of visitors. In the future, all these factors need to be reflected in the discriminatory pricing strategy of theme parks. Additionally, low-carbon investment in clean energy and green technologies has not been accounted for in the revenue function in this study. In future studies, cost subdivisions and revenue composition allocated to low-carbon activities should be considered. On this basis, a more operational discriminatory pricing strategy will be studied to improve long-term sustainable operations in the theme park industry.

_Li.png)