1. Introduction to Chilean Water Conflict Resolution and Its Origin: A Big Uncertainty

Water conflicts and tensions have been increasing worldwide [

1,

2]. Even though this can be associated with higher levels of scarcity, flood events, and water uncertainty, in general, the root of the controversy comes from a wider range of factors that include poor water management, water pollution, monopolization of access, negative externalities, threats to sustainability or limitation of future development opportunities, inability to manage, and insufficient regulation and investment in exploitation infrastructure [

3]. Due to the above, tensions over water are increasing, and in some cases becoming more violent [

1,

4,

5]. Thus, these conflicts have political, social, environmental, cultural, and economic implications, with all the complexity that this implies to arbitrate and coordinate the multiple interests that are in dispute. Correctly managing these kinds of conflicts can reinforce water resilience, water security, and environmental sustainability [

6].

1.1. Relevance of Water Conflicts and Their Resolution in Chile

In Latin America and the Caribbean region, Chile is considered a country from which valuable lessons can be learned because it has been successful in advancing the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Goal 6: clean water and sanitation. At the same time, the Chilean water system has been studied because of its strong market-based water rights system, complemented with self-governed water user associations (WUAs). It has been considered to have one of the most liberal water systems in the world [

7]. In addition to its progress in these areas, Chile also has challenges regarding water availability. Even though the country stores a significant amount of water (in global terms) of 695 mm/y, there is a great imbalance between where the people and the industries reside, and where the water is located, having highly productive areas with less than 2 mm/y of rain [

8]. These challenges are associated with being a developing country, including having a growing water demand, together with a significant lack of institutional coordination, all further aggravated by climate change [

9]. Climatic projections point towards a significant increase in the aridity of the country, especially in central areas, where the most important cities are located [

8]. Collectively, as with many other countries in a similar situation, there is a pressing challenge of rising conflicts between users, which have led, in past years, towards the emergence of a number of regulatory reforms involving water [

10]. In addition to this situation, the demand to secure access of water in rural areas, with equitable distribution among its users and consideration for the environment, has been one of the reasons behind the political and social process of a new Constitution [

10]. These processes, if not handled correctly, can escalate, such as with the water wars seen in Cochabamba, Bolivia [

11].

Indeed, the amount of water conflict is increasing and imposing pressure on the judicial system. This diagnosis is supported in a study carried out by mapping multiple legal disputes in water matters in Chile [

12] and in one that used data and text mining tools [

7]. Also, an analysis of conflicts solved by judicial courts in Chile between 2009 and 2018 identified an upward trend in these disputes, as well as an increase in cases that reach the Supreme Court, the final judicial venue for conflict resolution [

13]. Thus, disputes involving water are rising and are not being settled in the previous conflict resolution stages.

The first step of the Chilean water conflict resolution system is a collective one. WUAs themselves are allowed to solve conflicts between their members. However, this approach is rarely used. When individuals consider themselves affected by a particular situation, they usually bring it to the attention of the public authority, the

Dirección General de Aguas (DGA), or the competent court of law [

13,

14]. This explains why numerous conflicts end up in the hands of the justice system. The courts may ask the DGA or WUAs for their expert opinion, but they have no obligation to do so. Wider conflicts over water, such as between non-agricultural users or between private users and the DGA, are generally seen in the regional Courts of Appeal. As mentioned previously, these decisions may only be appealed to the national Supreme Court.

Even though several legal and normative reforms have occurred, there may be elements of the current Chilean water system that come from previous official documents. For example, the first national set of regulations governing water use—an executive decree from 1819 that set the size of an irrigation unit, the form of trading it, and the parties responsible for the water canals—to some extent defined Chile’s current allocation and reallocation system [

15]. Thus, some aspects regarding water conflict resolution in present times may come from historical conflict resolution mechanisms, similar to what studies have shown regarding collective action associations in Europe [

16,

17]. However, prior to 1819, water conflict resolution in Chile was not as clear and thus, this thesis has not been proved regarding the true origins of the water system in the country.

1.2. What We Know about Water Conflict Resolution during Colonial Times

During colonial times (i.e., 1600 to 1810), the fights surrounding water in the region occurred between competing water consumption activities, such as the demand to access water sources to develop urban settlements, water-powered industries, fishing, mining, and irrigation [

11]. For these issues, the country’s water management was guided by Castilian law through the

Fuero Juzgo (Jurisdiction Forum), the

Fuero de Castilla (Castilla Forum), the

Fuero Real (Royal Forum), and the

Código de las Siete Partidas (Code of the Seven Parties) [

18]. These legal provisions strengthened monarchical control of water at the expense of the local power—represented by municipalities—by declaring that certain uses of fresh water were monarchical royalties [

19]. However, following the conquest of Chile, the colonies generated their own forms of management and control in relation to water use and resolution of conflicts. As Spanish law contained some contradictory and entangled rules, especially in the absence of competent jurists, the colonies were able to generate their own jurisprudence [

18]. At the same time, the Spanish tradition favored custom over written law, so in the use and distribution of water it was common to proceed casuistically [

20]. For example, according to the Castilian legal tradition, the Indian Law established that the pastures, mountains, and waters common in the Indias were common to all their neighbors [

21]. According to the Spanish colonies, the neighbors were members of their own colonies, and they established the limits of their own properties and granted themselves volumes of water (merced) as rights of use, ignoring previous settlers [

18]. Thus, even though the colonies were subject to Spanish law, in practice, the subjective implementation of the norms led to a unique colonial governance system. Yet little is known about how water conflicts were treated and solved during colonial times, how the conflict resolution system evolved during that period, or which elements influenced Chile’s actual system.

1.3. What Can We Learn from Looking into the Past of Water Conflict Resolution in Chile

The question that arises, then, is what can we learn from the past, and can we gain a deeper understanding of how certain elements, present in the current legislation, came to be? Side questions of this project include how water conflicts were treated and solved during colonial times. Is it possible that water conflict resolution from Chilean colonial times (pre-1819) influenced the current Chilean system? Also, is it possible that, at present, we are facing problems that were solved more efficiently in the past? Answering these research questions can help us unveil where the current problems of the system are, to consider this knowledge in current regulatory processes, and to avoid making the same mistakes. An effective conflict resolution scheme for water issues, in addition to supporting a more peaceful environment, provides for better decision-making and promotes an overall recognition of the legitimacy of the water system. Unsolved, these water conflicts impact economies, political arenas, social stability, populations, and the environment [

3].

Despite this relevance, most of the discussion and analysis of the history of water conflicts focuses on transnational, or interstate, disputes [

22]. These have focused on general international water conflict and its history [

23], transboundary water management conflicts [

24], or particular case studies, such as the history of water sharing between India and Pakistan [

25]. Also, the historical assessment of conflict resolution sheds light on the effectiveness of different mechanisms of solving water conflicts [

26]. For example, historical evidence demonstrates that water tensions often become catalysts for cooperation [

27]. Few studies analyze historical water conflicts and their resolution mechanisms in Chile [

28,

29]. Historical water-related studies have focused on the analysis of the legal regime of water and the evolution of its legislation [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] or on works about the potable water supply to Santiago [

35,

36,

37]. However, the evolution of water conflicts during colonial times, as well as its current influences, has not been studied. Thus, history shows that better mechanisms and far greater efforts are needed to address water conflicts and their resolution mechanisms, and there is a clear need for advancing in this research stream.

The following study presents the results of a review of nearly 40 judicial files with water-related conflicts from the years 1691 to 1804 of the Real Audiencia de Santiago (Royal Hearing of Santiago), the court of law that ruled during the colonial period, as well as of the gatherings of the Cabildo, where neighbors discussed administrative, economic, and political problems. In addition, a review of a complementary bibliography was used to support the analysis. The goal is to understand how conflicts associated with a common good, such as water, were managed during the colonial period, and to obtain lessons from this historical knowledge. A secondary objective is to compare past and present water conflict resolution mechanisms to provide insights into how current water systems could be improved.

2. Conceptual Framework, Data, and Methodology

To understand the ways in which water conflict resolution worked in colonial times, an adapted version of the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework was used. The framework, derived from institutional economics, was conceived to analyze how institutions operate and change over time [

38]. It is targeted towards social ecological systems and communities without state intervention and their governance over common resources [

39].

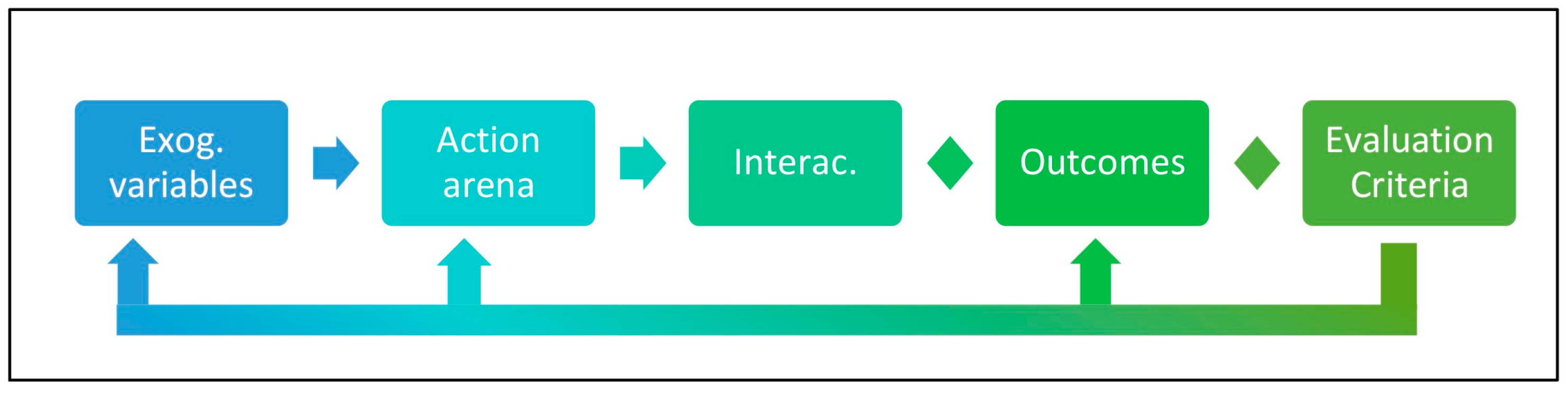

The IAD framework involves the analysis of the interactions and outcomes of an “action arena” formed by the action situation, a social space where the actors interact, solve the common problem, and exchange goods and services, together with actors that participate in the situation. This action arena depends on exogenous variables that change the analysis of the case study as they vary and lead to interactions that generate outcomes that can be evaluated afterwards [

40]. The components and their relationships are presented in

Figure 1.

With regards to natural resources, the framework has been used to study conflict resolution [

43]. In this context, a similar research [

44] used the framework to study the need for the coordination and cooperation of different environmental groups [

31], and later on, it was used to study the role and capacity of governments to facilitate local collective action [

32], with both studies regarding environmental conflicts.

In the current study, the framework has been adapted to facilitate an understanding of how water conflicts were solved during colonial times, specifically regarding which institutions were in place and what were their main roles. Thus, for this particular study, the “actors” of the “action arena” were sub-categorized into judges and those who supported their participation, that is, public authorities and stakeholders, all being an important part of the actions and decisions taken in water conflict resolution during Chilean colonial times. A similar modification was performed, adapting the framework to the local context, in [

44]. Also, the “exogenous variables (EV)” component was subdivided to capture different contextual elements in the analysis, considering water availability, which refers to the water biophysical situation, such as precipitation trends, scarcity or drought situation, floods, or water quality problems, and considering the rules, that is, the regulatory context, including formal rules, property rights, and historical considerations, as well as any exception or deviation from them. This follows a similar classification made in [

45]. A “broader setting” component was included to highlight any social, economic, and broader political contexts affecting the conflict resolution system in place, following a suggestion of variables in analyses from water studies [

46,

47] applying the related Socio-Ecological Systems (SES) framework [

41]. Finally, the “outcomes” component was replaced with trial results, to consider any recollection of the jury’s final decision, especially regarding innovative solutions, social consideration, ecological performance and externalities; and the “evaluation criteria” component was replaced with any data or information regarding post-trial analysis. The final version of the framework and its components are illustrated in

Figure 2.

For the analysis, the review of the transcripts of nearly 40 judicial files with water-related conflicts was used as primary data. These transcripts come from the proceedings of the Royal Hearing of Santiago, from 1691 to the early 1800s, and from the Cabildo sessions carried out in Santiago between 1541 and 1802. These have been transcribed from old hand-written Spanish into digital spreadsheets. To narrow down water conflicts from other type of disputes, key concepts have been used, selecting water cases from the full digital library of trials. Afterwards, a review was performed on these cases to corroborate the selection. Given the inexistence of a categorized archive system, we cannot state that the water trials compiled are all those that occurred between the years analyzed, but we are confident that we captured most of the cases. Also, to complement these transcripts, secondary information was retrieved from a bibliographic review carried out regarding articles focused on explaining the social, economic, and political context during a similar time period.

A qualitative content analysis was carried out, based on a codebook. The codebook contains a list of the adapted IAD framework components, used as codes for this qualitative data analysis research. It included a definition of each of these components, along with examples of what was considered in each of them. Translated summaries of the files and text analysis can be found in the

Supplementary Materials, together with the codebook used.

The proposed method provides for more detailed insights and deeper discussion, since it has a qualitative core. However, it has the limitation of having risk of bias, both in the selection of cases and in the analysis [

48]. In addition, because of the number and location of the case studies analyzed, there could also be bias from the source of the information. Thus, any conclusions and recommendations have to account for these limitations.

3. Results and What Do the Trials Reveal Regarding Water Conflict Resolution during Colonial Times

3.1. Actors, the Decision-Making Process and Their Interactions

3.1.1. The Judges or Deliberative Bodies

The Real Audiencia (Royal Hearings) contain the lawsuits between private parties that disputed the use of a water source, as well as the motives, arguments, and interests that substantiated the demands for water rights. The judges or hearers were the ones who delivered and made proclamations on the different conflicts at these Hearings. They were the last step for conflict resolution in the colonial lands, so they were highly efficient in the sense that most trials were solved within the first hearing. There are specific cases where the trial lasted for longer, but the majority lasted two years. There is one outlier case that lasted 24 years because it included several subsequent trials (Comuneros de acequia de Aedo, Domingo Santiago, Pedro Jose de Prado, Royal Hearing 1804–1828, Vol. 1879, page 172), but in general, it was a highly efficient and resolutive process.

There are indications of the creation of a “nested” conflict resolution system over the course of the colonial period, because later trials consider and mention previous local trials and judicial resolutions. Also, in the judicial branch, below the Royal Hearings and local Judges, the

Juez de Aguas (Water Judge) would review initial cases regarding water distribution and management (

Cabildo session 1772, Vol. 34). At first, the functions of this Water Judge were more operational than regulatory, and with time the position came to acquire a remarkable stability [

36]. This institution even continued after colonial times, surviving the uncertainties that accompanied the independence process and all the political, economic, and social changes that came with it [

49]. The judges of the Royal Hearings then settled disputes that were not solved by the Water Judge, as well as receiving the appeals from local judges’ decisions [

18].

An interesting figure, and an element that appears in several trials, is the

Alarife. This person oversaw the water distribution among users and monitored the compliance with local rulings [

18]. For example, the

Alarife was in charge of monitoring the obligation of urban water users to clean the ditches [

36,

49]. Each neighbor and resident of the city was supposed to contribute a worker with a shovel or hoe on a designated day, and the

Alarife would be in charge of following the cleaning process [

49]. This person, as the “eyes” of the water community, would be later used as the means of proof during water trials that would stand out above all other evidence, and would support the work performed by the Water Judge [

49]. Thus, not only were there local institutions “nested” in higher forms of conflict resolution institutions, but there was also an operational branch, for surveilling and assuring the regulations are accomplished on-site, thereby strengthening the institutional system surrounding water conflict resolution.

3.1.2. The Cabildo as Representative of the People

Any issue regarding water also reached the

Cabildos. The

Cabildos were municipal corporations created by the Spanish kingdom for the administration of the cities. They were legal representatives of the city, similar to the City Council, that is, the municipal body through which neighbors discussed judicial, administrative, economic, and military problems. From the first years of the colony these institutions constituted an effective representation mechanism for the local elites against the Spanish royalty and its bureaucracy [

18]. With the evolution of the water management system, the

Cabildos positioned themselves as the first step for solving water disputes between neighbors, and they annually chose the Water Judge.

Although the

Cabildo was the institution that should have defended and acted as a representative of the people, it appears that at least at the beginning of colonial times, it played a weak role. First, the

Cabildo did not consider the land’s original water users, usually called natives or Indians, during trials; moreover, several times, the

Cabildo not only favored the Spaniards, but protected the elite of the colony [

18]. Also, participating in trials or hearings of the

Cabildo was expensive, and few could afford it at the time, meaning that it was exclusive [

49]. However, the

Cabildo was the institution which brought to light water matters and proposed solutions at a city level, so it was involved in issues that concern the whole city as a community. In the

Cabildo, the discussions to bring water from the Maipo River started only once the main source for the city was proven uncertain (

Cabildo session 1729, Vol. 19, page 29; a map of the city of Santiago surrounded by the Mapocho and the Maipo Rivers can be seen in

Appendix A). Here, the figure of the

Corregidor appears for the first time as a figure bringing voice and support to the people.

Also, civil society was considered in trials, at times, as witnesses. For example, in an early trial, the Royal Hearing proposed the creation of a structured interview that the parties should administer to neighbors (Juan Baptista de las Cuevas against Manuel Ramírez, Royal Hearing 1774–1777). It must be noted that neighbors were usually considered and mentioned throughout the reviewed cases.

3.1.3. Other Public Authorities

In different cases, the work performed by the Cabildo was respected and even supported by other political figures. For example, during a drought that occurred in 1729, communal institutions such as the Corregidor facilitated the work performed by the Cabildo by taking a vigilance role. In this case, it even hired guards to keep a safe eye over the city canals (Cabildo session 1729, Vol. 19). On a second occasion, the Corregidor helped the Cabildo by evaluating the supply and distribution of water in the city, as well as executing action plans based on their diagnoses. Also, in other sessions, the figure of the Corregidor is seen endorsing previous settlements (Cabildo session 1742, Vol. 31). In a second example, in 1763, there was a debate to bring water to Santiago from a parallel river, Estero de Ramón, and the Governor himself proposed that prisoners under his watch could be used for building the canals (Cabildo session 1763, Vol. 33). Thus, the function of the Cabildo, as well as the other communal authorities, was respected by the rulings of the Royal Hearing, as well as supported by the Corregidor and the Governor.

3.2. The Broader Setting of Trials Reveal Value for Social Issues

Against a background of economic instability and marked social classes, trials reveal a specific consideration for the most vulnerable. For instance, the mention of a “poor-people” litigator appears in the documents. In a trial involving a recent widow who had been deprived of her water allowance, this specific kind of lawyer was the one in charge of representing her, because of her poor economic and social position (Josefa Maldonado against Juan Infante, Royal Hearing 1820–1822, Vol. 1690). Even though this appears mentioned only in one case, it seems that it was not rare and, according to a study conducted for the end of the colonial period in Chile [

50], the poor had the right to represent themselves at these courts without paying.

Even though contact with the Spanish kingdom is scarce in the documents, when it appears, it shows a sense of care towards the new colonies. For example, despite the fact that water was scarce and already considered valuable, Indigenous communities were protected and prioritized in using it, at least under the Royal Hearing trials. This is demonstrated throughout the case of 1705, where Luisa Parras was in charge of a group of “Indians”, but was deprived of water (Melchora Mena against Luisa Parras, Royal Hearing 1705, Vol. 1690). Relevance to these Indigenous group and their importance for the kingdom was stated, and thus, their caregiver was given a secured water provision. Here, the care for the Indigenous communities can be contextualized as a patrimonial consideration, and not because of cultural recognition. For example, although Castilian Law established that waters are common goods and, thus, they should be treated as common to all the neighbors, these neighbors were

Indian hosts and not natives themselves [

18]. Thus, the trials show that social aspects were relevant and considered by judges during colonial times, notwithstanding the fact that Indigenous communities were not directly included as such.

3.3. In a Context of Water Scarcity, Conflicts for Water Were Becoming Violent

Drought is a relevant issue considered throughout the trials. During colonial times, water stress led to conflict as well as to economic impacts and, therefore, was generating more awareness and even violence between users. According to one of the Cabildo sessions, sometimes the conflicts were such that people required weapons to protect themselves while extracting water (Cabildo session 1778, Vol. 34, pages 133–134). Also, there were vigils of farmers in place to prevent the theft of water, and some farmers had been financially ruined because they were not able to irrigate enough (Cabildo session 1778, Vol. 34, pages 133–134). Thus, the value of water and the costs of water conflicts were already evident at this time and had even led to a violent scenario.

3.4. Rulings Adapted towards Local and Social Needs

The rules were broad and adapted to fit local and social needs. For example, there are rulings favoring local issues, such as social matters in terms of food production. In the example of the trial between José de Ureta and Juan Antonio Araos, the resolution favored local needs by approving the construction of a wheat mill near Araos’s vineyard estate, affecting his harvest, which was justified on the basis that bread was a more important asset for Santiago than wine (Royal Hearing 1768, Vol. 1275). Also, there are several decrees in the Cabildo sessions that were instated for the city’s needs. Examples of these are rulings regarding water scarcity measures (Cabildo session 1742, Vol. 31; and 1772, Vol. 24) and sanitation matters (Cabildo session 1729, Vol. 19; 1761, Vol. 33; and 1778, Vol. 34). In all of them, specific rulings are made favoring giving water to the cities and towards a better sanitary management.

The search for a new water source for the main city of Santiago, as well as for having water intakes in the cities for human use, is a constant preoccupation. In the Cabildo discussions, arguments towards building water canals and improving current infrastructure invoke a lack of drinking water for certain areas and potential fatalities expected from drinking poor-quality water (Cabildo sessions 1742, Vol. 31, page 38). In one of the trials, the main argument of the session was the potential demise of a whole neighborhood because of water uncertainty (Cabildo session 1729, Vol. 19, page 29). Here, the relevance towards safe and secure drinking water is evident and prioritized. In the Royal Hearings, the same argument is used in a case of dispossession of water (Josefa Maldonado against Juan Infante, Royal Hearing 1820–1822, Vol. 1690). Even in privately held trials, the social worry for the population’s heath due to their access to water was present, and the rulings favored this sector.

3.5. Trial Results Reveal Contradictions, Innovations, and Sanctions

In most trials, the results follow the previously stated rules, giving high priority to traditional uses as well as to food production and social concerns. However, there are some cases where contradictions appear. In one case, even though historical use was generally upheld in trials, judges prioritized that the water source was located in the property of the one using it regardless of proving it was used historically (Juan Baptista de las Cuevas against Manuel Ramírez, Royal Hearing 1774–1777). As a second example, the judges decided in favor of equal distribution of water among parties in the case of Magdalena Negrete versus Antonio de Carvajal, Vicente Carrión, and Gonzalo de Córdova (Royal Hearing 1694, Vol. 755, pages 113–191). However, in another similar situation, the trial concluded in favor of the distribution of the water, not equally, but according to how much each of the parties farmed (Josefa Maldonado against Juan Infante, Royal Hearing 1820–1822, Vol. 1690).

Regarding innovative solutions, in different trials, workers are used by the parties involved as a surveillance mechanism. Even though for a more proper monitoring system to be implemented these elements would need to be permanent, it worked in certain situations. In 1729, for example, a drought hit Santiago city, and guards were hired to watch for neighbors manipulating the river flow (Cabildo session 1729, Vol. 19). In the same drought, there was a proposal for hiring guards for a year. However, the idea was abandoned as soon as the drought was over. Thus, they developed a monitoring system carried out by users. These systems did not work permanently and just appeared sporadically as a response to droughts.

In addition, creative and low-cost solutions were put in place for conflict resolution. Often, the use of field laborers was chosen for the surveillance or construction of projects, as well as other solutions where costs are shared. The aforementioned case of prisoners being used to build a water canal for the city of Santiago provides an example (Cabildo session 1763, Vol. 33). Using prison labor in this way was justified by the fact that there was a proportionally high population of criminals who committed minor crimes and were not able to be sent to Spain to serve their sentence. These prisoners were seen as “idle” and could help for free. This reason was also used in 1772 to build a water passage to the main square of San Isidro village in Santiago (Cabildo session, 1772, Vol. 34).

Regarding sanctions, many times high or very strict sanctions were used in response to a first offense. There is just one identified case when a warning is mentioned, but the warning came together with a fine. The case sought to demand that residents clean their own irrigation ditches because canals had filled with dirt during a serious drought that affected the city of Santiago (Cabildo session 1748, Vol. 32). More commonly, sentences found in these transcripts are the opposite, and misdemeanors such as being disrespectful were sanctioned with jail time. Such is the case of Domingo Frías, who was found guilty after members of the Cabildo noted that he had not complied with a mandate, and when hitting the table with rage, he was sent immediately to prison (Royal Hearing 1775, Vol. 1044).

3.6. In Post-Trial Analysis a Lack of Evaluation Was Found

There are no perceived instances of post-trial reflections or a formal process for evaluating the performance of the conflict resolution system. Across all documents reviewed, the modifications that took place, such as the incorporation of new actors for the strengthening of the institutional framework, came from sustained petitions from organized sectorial groups (mainly farmers) at the Cabildo meetings.

Thus, as a general reflection, resolutions of colonial conflicts started out as small village trials, where the judges knew the people in question and settled issues accordingly. These institutions could take action supporting specific areas of interest for the city, such as food and water security, and could provide assistance in areas of social concern. Over time, the colonies’ water problems became more complex because cities started growing and water scarcity issues became more serious. Here, contextual factors were crucial in forming the institutional scheme that developed during colonial times. The appearance of the

Alarife and the empowerment of the Water Judges as a primary conflict solver show a response to the need for a more solid institutional system. This evolved into a “nested” conflict resolution scheme, allowing these roles to continue to manage conflict at small and local trials. The same happened with the role of the

Governador and the

Corregidor, as supporters of the

Cabildo rulings. Both gained strength and became more active members of trials and discussions as the colonial process developed. With a stronger institutional system and with local roles supporting higher level conflict resolution, despite the fact that colonial norms had room for interpretation, the judges and their rulings were respected, sanctions were imposed, and different members of the citizenry participated in them. Altogether, generally, this was a socially validated conflict resolution system and a robust model. These results, together with the study of each of the components reviewed under the adapted IAD, can be seen briefly in

Figure 3.

Here, it must be stated that this analysis did not consider the conflicts between the Spanish colony and local Indigenous communities. Even though there are cases where these communities were protected, the Spaniards in charge of them benefited most. Original Indigenous communities were not directly represented and were not included in the colonial system.

4. Discussion: Have We Learned Anything from Colonial Times?

4.1. Comparing Past and Present

4.1.1. Actors: Fragmentation Has Led to Discoordination and Disparity in the Treatment and Resolution of Water Conflicts and Trust Issues

Currently, there is an issue regarding coordination between institutions. Even though the formation of WUAs involves a judge’s resolution and a complex procedure where the public institution is consulted, the DGA acts as a second reviewer, since WUAs must again request registration [

9,

51]. This has led to a number of cases where communities are already organized and operating, yet their registrations are pending and thus they cannot access public funding opportunities [

52,

53]. Thus, a discoordination between authorities limits the work performed by judges and generates a sense of mistrust towards the system [

54]. These types of situations were present, yet being solved, during colonial times. Then, any major decisions involving water went through the

Cabildo, and at the same time, the

Governador or the Water Judge would be present and participate [

18]. Thus, the validity of any decision was aligned among all users.

In modern water trials, there is a disparity in the criteria used for the resolution of conflicts that generates meandering or incoherent trial results. Here, the same types of cases are resolved on the basis of different criteria, affecting equality and people’s trust in the law and in courts [

13]. Even though during colonial times some contradictions in the trials’ resolutions were seen, these usually were responses to adapt rulings towards social needs. Currently, these contradictions have generated, once again, a sense of injustice and mistrust in the courts’ resolution, thereby jeopardizing the system.

4.1.2. Environmental Issues Have Risen, While Social Ones Persist

Water stress in central Chile has increased in terms of temporality, territorial scale, and intensity, generating a structural deficit of surface water available to cover the water demands [

55,

56]. The surface water deficit has been partially covered by groundwater extraction, threatening the sustainability of aquifers. This has contributed to the conflict in different areas of the country between water for agriculture and for human consumption [

57]. As mentioned earlier, this conflict has increased significantly and has become alarmingly violent, especially in dry years [

58]. More so, water is a part of most socio-environmental conflicts, the majority of them related to mining or energy projects [

59]. Thus, water matters are still pressing issues and we still have not developed an effective system for dealing with these conflicts.

Moreover, after a period of social movements and demonstrations that began in Chile in October 2019, the country has been going through a Constitutional reform. Many of the complaints are related to social and environmental topics, and water and the way it is managed is one of them [

60]. For example, the difficulties in correctly assessing the social and environmental outcomes of water trading schemes, and the ethics of applying economic principles to a resource such as water, have raised concerns regarding the fairness of the current market-based system [

7]. Thus, the distribution of scarce water has been a source of conflict, even since colonial times, but nowadays environmental concerns have risen and are adding more pressure to the conflict resolution system.

A space for incorporating social concerns from non-water rights-holders has been through the protection action established in the Constitution of Chile. For environmental claims, specific courts were developed in 2012 (Law 20,600, published on 28 June 2012). These institutions have been used to resolve specific cases that are increasing in frequency. The protection action, for example, receives cases related to water quality, access to drinking water, claims regarding the modification of riverbeds and their effects on the free runoff of water, and the irregular extraction of these, as well as conflicts between user organizations and their members, among others [

13]. Regarding environmental courts, they specialize in resolving environmental disputes, where 65% of them have involved water topics [

61]. Thus, social and environmental conflicts have a space to be considered and treated as special cases.

4.1.3. More Complex Topics Are Now in Place

Regarding the topics in conflict, the relevant focal points are watershed conflicts among users, groundwater overexploitation, social and environmental conflicts, and conflicts of a political and regulatory nature [

59,

62]. These have become more complex and harder to manage. Even technical aspects, such as defining water availability, has become harder to do in a generalized scenario of drought and climatic uncertainty [

13]. The same goes for treating environmental and social components that have also become more conflictive, since there are more cases regarding impacts on water quality and its role as an ecosystem sustainer and considering everything related to the human right to water [

13,

14]. Thus, water conflicts in Chile have been increasing and have become more complex, and the current system has not been able to cope with them.

New variables and additional demands in water security contexts have been added in recent years. For example, a nationwide report by the association

Chile Sustentable [

58] conducted a case-by-case examination of sub-national conflicts and found increased violence in the parties’ actions. These studies also state that judges are often not specialized in the complexities of water or in the treatment of these new pressing disputes [

13,

14]. This suggests a lack of what is typically a cornerstone of achieving a successful legal system and implies that courts face great challenges when handling cases of water security.

4.1.4. The Length of Trials of the Judicial System Has Increased

The majority of conflicts, especially in recent years, have been settled by the final stage of the judicial system, the Supreme Court. This trend can be explained by the greater awareness of the litigants about their rights and possibilities of action, together with a greater sense of injustice in rulings and resolutions pronounced by previous judicial stages [

13]. However, for conflict resolution, WUAs act as the first step (Water Code 1981, Art. 244). Thus, the Board of Directors of each WUA should arbitrate in cases of conflict arising between users. This would be more effective than utilizing the regular legal process. However, the judgment of the WUAs is not always considered as impartial and the procedures are not always clear, leading users to invest money and time in pursuing a more seemingly fair resolution.

Studies also agree that an additional unsolved issue is the duration of the judicial processing of water conflicts, some of them lasting an average of 2.5–7 years [

13]. This was also identified in a study that interviewed local water associations, which responded that legal processes take too long and do not solve conflicts quickly enough [

14]. Considering the current urgency of water needs, entering these trials implies a significant time investment. This brings into question whether the initial stages in the legal system (e.g., WUAs) stopped offering a more local view, such as the one offered by the Water Judge during colonial times. Moreso, these institutions went through a maladaptive development, using the concept provided by Popovici et al. [

54]. If initial steps of the conflict resolution process would provide more confidence in the system, fewer cases would reach the Supreme Court, and would take less time.

4.1.5. Changes in the Ones Doing the Claims

In the past, most claims were between farmers. Even though agriculture is currently still the main consumer of water, at present times, most conflicts over water take place between individuals and the public authority, the DGA [

7,

12,

13]. This is because the administrative system for constituting and modifying a water use right involves going through courts. This was already present but only eventually used during colonial times, since only the

Governador or the

Cabildo could issue or validate a water permit in an official session [

18]. However, in recent years this trend has started to rise, since individuals and WUAs modifying water rights have been watching and increasingly opposing these claims [

13]. This may also be explained by the increased awareness and greater appreciation of water as a resource.

Conflicts between individuals are still the leading causes of protection actions in Chile, although a significant number of these happen between individuals and WUAs [

13]. This is due to WUAs becoming stronger and because of their duties regarding distributing water, controlling and enforcing this distribution, keeping records, and as a first step in conflict resolution among users where they act as representatives of their users’ needs [

9,

51]. So far, researchers indicate that WUAs have been very much aware of performing these administrative functions and that they have the normative and administrative tools for good management of them, despite the fact that many still operate in precarious conditions [

15,

52,

63]. Here, WUA members, together with the group dynamic in place, have become a crucial element in their capacity to respond to external disturbances, such as environmental variations, as a study carried out [

64] determined. In theory, these associations should involve all users of the watershed, including agricultural, mining, urban, hydroelectric, tourism, environmental, and industrial users, as well as anyone else who uses those waters. However, there are few instances of integration with electric companies that operate hydroelectric plants. Hydroelectric plants have, on occasion, generated conflicts between farmers and generators [

58]. A step in the right direction occurred in the north of the country, where electric generating companies and WUAs have developed agreements to share water resources (e.g., Huasco River Hydroelectric Power Plant). Even though during colonial times the figure of the

Cabildo was supposed to represent the people, in reality it was focused more on local elites and it did not truly represent all water users [

18]. Thus, greater involvement of communal organizations in conflict resolution could be considered a modern trend, but not a trend present during colonial times.

4.1.6. Post-Trial Analysis Is Still Lacking

The current judicial system is now wider, and in addition to the Ordinary Courts of Justice, water cases can also go to the Free Competition Court (Tribunal de Defensa a la Libre Competencia), Arbitrage Courts (Tribunales Arbitrales), and Environmental Courts. Any instance where disagreement still holds is generally seen in the Courts of Appeal. These decisions may only be appealed to the national Supreme Court, which provides for yet another process to review the conflict. However, there is still no perceived instance where an official process for evaluating the performance of the conflict resolution system is in place.

In conclusion, there has been a clear evolution in all components of the IAD framework investigated. Since colonial times, water conflicts and their resolutions have been challenging. Due to the fact that water issues evolve, some elements of the system have also evolved, but the main ideas have been present since colonial times. The social worries during colonial times also exist in the present, but environmental and climatic challenges additionally exist in contemporary trials. During the Royal Hearing trials, as well as in the Cabildo sessions, the rulings were community or socially focused, and they were adapted to address local needs with the needs, in this case, being the sustainable and clean provision of water and food for cities. Thus, there is an aspiration for the current system to accomplish the same. Even though the current system includes specialized courts, it is still not able to carry out water distribution while also taking care of local social and environmental claims. Thus, in current water policy reforms, there is not only the pressure to generate an efficient system to distribute water throughout basins, acknowledging the diverse water scenario of Chile, but there is also the added demand of addressing economic, social, and environmental needs.

The analysis of the trend from colonial to modern times is presented in

Figure 4.

4.2. The Need for Effective Water Conflict Resolution Schemes

As can be seen from this analysis, the system for treating and solving water issues has evolved since its development during colonial times. From the cases surveyed here, the development towards a transparent conflict resolution system for treating these particular matters was evident.

Successful conflict resolution mechanisms involve the presence of trustworthy and well-defined institutions, aspects which were present in colonial texts. Indeed, in the past, the function of each actor was clearly defined and there was a tendency towards their empowerment during the colonial process. This led to some institutions, such as Water Judges, Alarifes, and Cabildos persisting beyond the colonial period. However, even though the Cabildos were the institution responsible for representing all actors, they had issues with misrepresenting some, affecting the legitimacy of the process that could have caused their later disappearance.

During colonial times, trials concluded quickly and they could address specific political concerns in their resolution mechanisms. More so, the relevance of the economic and social context in which the cases developed is something that has lasted until present times. Currently, environmental concerns are an added layer of context to the specific water issues that must be dealt with. Even though spaces have now been opened to resolve these particular claims, these places allow for less public and political intervention than they did during the colonial era. However, this space for permissive and more independent action also meant that the system was not equitable or coherent, at least regarding water matters. At the same time, the system did not integrate all actors, ignoring native communities and their pre-established system.

It seems that some aspects of colonial times, such as the nested schemes and the strong institutions, are no longer present. On the other hand, some problems are persistent in the current system, apparently as if nothing was learned. Historical conflicts over water reveal the social reality of a country, together with the way in which the legal norms are being applied. Thus, past experiences should be considered in any review or possible reform of the regulatory model, as well as in current policies.

The adapted IAD framework was useful for identifying the dynamics and changes of the conflict resolution system analyzed here. It permitted an understanding of the social and political context, together with relevant cultural aspects, and an exploration of all actors, their interactions, and their changes over time. However, even though this study uses transcripts of water trials together with secondary information and is strengthened by a literature review, further studies are required to solidify the results. For example, the same analysis could be performed looking at the Peruvian conflict resolution cases and institutional system, since it is a neighboring country to Chile and has gone through a similar colonial process, which could help clarify the results of this study.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The main conclusion of this papers points to the need to review past documents and experiences to understand the current system and to avoid making the same mistakes. This approach, since the conflicts reviewed convey practices that have lasted until the present day, reveals a history of longstanding multiple legal and normative reforms. It also shows the relevance of reviewing conflict resolution cases, more than the legal framework itself, since the jurisprudence and practice may sometimes be more official than the formal law.

Thus, following the Chilean case study, we propose some recommendations on the resolution of water conflicts, based on the lessons drawn from the events that occurred during colonial times. These recommendations can also be applicable to other countries and regions with similar characteristics, in terms of water availability and water institutional schemes. The following are our recommendations: Firstly, to identify and understand where, when, and why the identifying elements of the legal and institutional water system of each country were developed. Secondly, to support and strengthen the institutional framework of the country, considering a structure or figure that can adapt to future challenges and demands. Third, to align present and future normative reforms towards this knowledge.

Overall, the study also points out general conclusions and recommendations regarding the treatment of conflict over water resources. First, all users and actors, at all scales and locations, should be considered and be able to have a voice in the conflict resolution system. Second, nested schemes should be promoted in conflict resolution systems, empowering local water judges. Third, a strong institutional system should be promoted to support this nested scheme, with independent voices and secured resources. Altogether, water conflict may be a constant, but its treatment and resolution may help to create a more peaceful, just, sustainable, and inclusive system.