Tourists’ Revisit Intention and Electronic Word-of-Mouth at Adaptive Reuse Building in Batavia Jakarta Heritage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

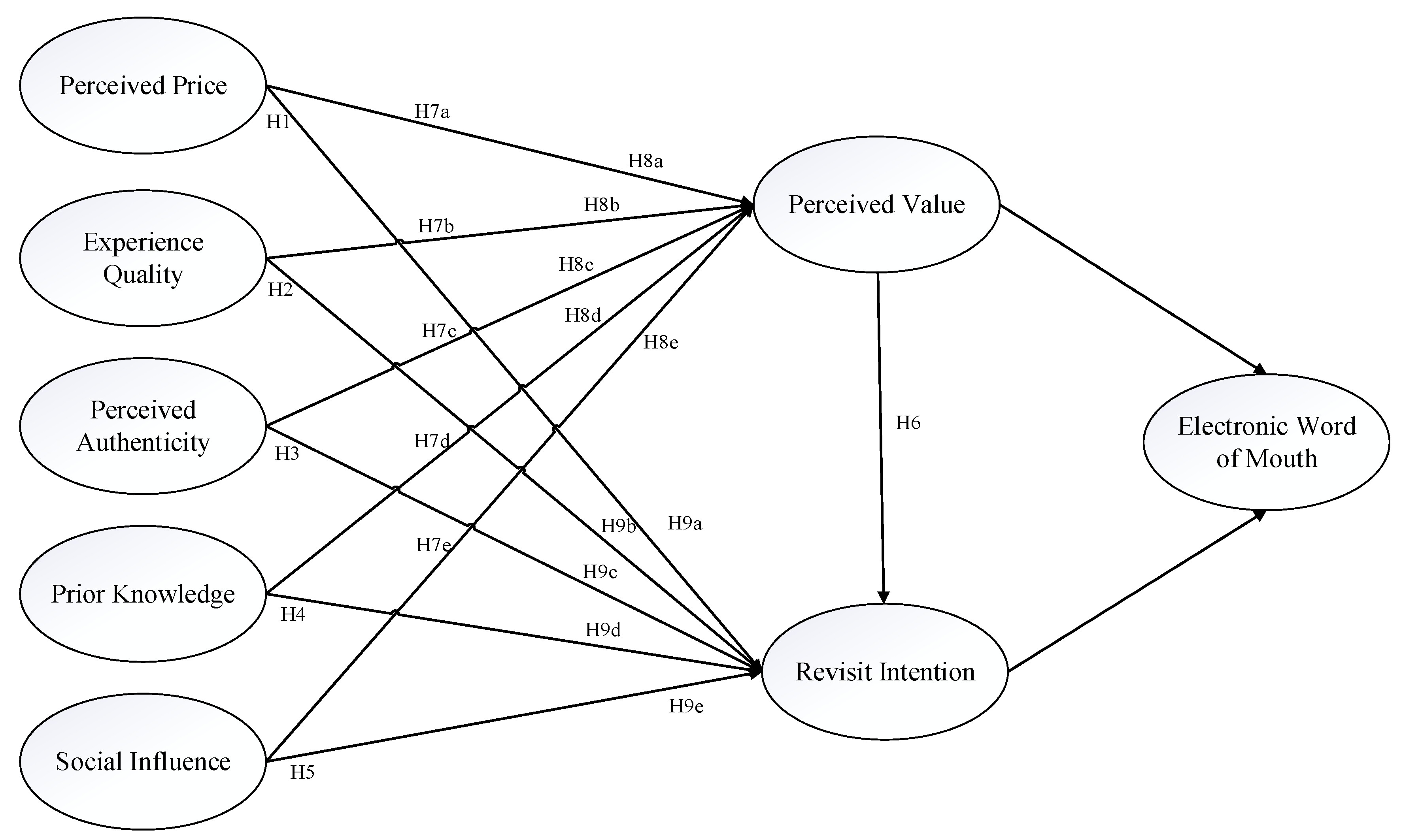

2. Literature Review and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Adaptive Reuse Building

2.1.2. Electronic Word-of-Mouth

2.1.3. Perceived Price

2.1.4. Experience Quality

2.1.5. Perceived Authenticity

2.1.6. Prior Knowledge

2.1.7. Social Influence

2.1.8. Perceived Value

2.1.9. Revisit Intention

2.2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Profile

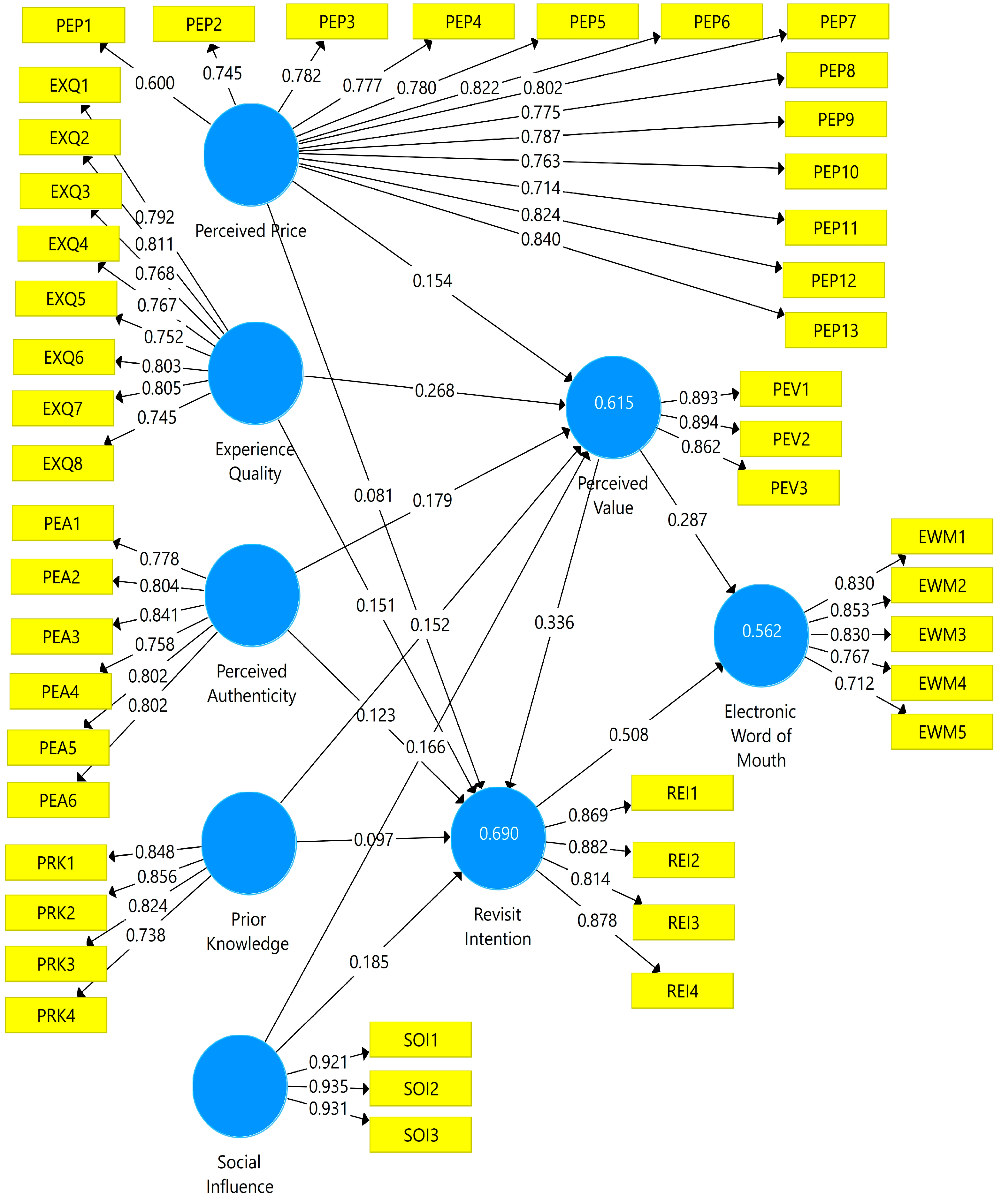

3.2. Evaluation of Measurement Model

3.3. Hypothesis Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ahmad, A.G. The effects of community factors on residents’ perceptions toward World Heritage Site inscription and sustainable tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F. Heritage tourist experience, nostalgia, and behavioural intentions. Anatolia 2015, 26, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. Links between tourists, heritage, and reasons for visiting heritage sites. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Biran, A. Heritage site perceptions and motivations to visit. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, G.-T.; Goh, Y.-N. Tourists’ intention to visit heritage hotels at George Town World Heritage Site. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, C. Authentic housing, authentic culture? Transforming a village into a “tourist site” in Manggarai, Eastern Indonesia. Indones Malay World 2003, 31, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, P.A.; Cantoni, L. Indonesian Tourism and Batik: An Online Map. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2019, 16, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawati, T.W.; Marjo; Paksi, T.F.M. Reformation on Local Tourism Permit Practice in Indonesia: A Case in Semarang Regency. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Widaningrum, A.; Damanik, J. Improving Tourism Destination Governance: Case of Labuan Bajo City and the Komodo National park, Indonesia. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 5043–5051. [Google Scholar]

- Ardiyati, W.; Wiwaha, J.A.; Hartono, B. An exploratory study on traditional food of Semarang as a cultural and heritage product. In Heritage, Culture and Society: Research Agenda and Best Practices in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry, Proceedings of the 3rd International Hospitality and Tourism Conference, IHTC 2016, Guangzhou, China, 14–17 July 2016; Proceedings of the 2nd International Seminar on Tourism, ISOT 2016, Bandung, Indonesia, 10–12 October 2016; Radzi, S.M., Hanafiah, M.H.M., Sumarjan, N., Mohi, Z., Eds.; CRC Press: Bandung, Indonesia; Balkema: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2016; pp. 667–670. [Google Scholar]

- Permata, D.D.; Kuswandy, A.S.; Riza, A.I.; Sakti, P.F.; Diana, T.I. The Centrum-Bandung: Adaptive Reuse at Heritage Building as Sustainable Architecture. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmadina, M.; Kusuma, N.; Arvanda, E. Wall finishing materials and heritage science in the adaptive reuse of Jakarta heritage buildings. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; Institute of Physics Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Putri Nurmala, D.N.; Abduh, S.; Sari, T.K. Floating photovoltaic in Kota Tua Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 3rd Borobudur International Symposium on Science and Technology 2021, Magelang, Indonesia, 15 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhikuning, A.; Priambodo, B.; Sukarnoto, T. Potential waste to energy in Kota Tua–Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 3rd Borobudur International Symposium on Science and Technology 2021, Magelang, Indonesia, 15 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Purwantiasning, A.W.; Bahri, S. Enhancing the quality of historical area by delivering the concept of transit-oriented development within Kota Tua Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Sustainable Architecture and Engineering, ICoSAE 2020, Jakarta, Indonesia, 28 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bahri, S.; Purwantiasning, A.W. Designating the preference of tram shelter as a part of transit-oriented development’s concept within Kota Tua Jakarta using fuzzy logic. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Sustainable Architecture and Engineering, ICoSAE 2020, Jakarta, Indonesia, 28 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhani, A.; Wartaman, A.S.; Fatimah, E.; Adriana, M.C.; Sitorus, A.M.; Zikra, A. The Best Alternative for Revitalising the Asset Area of PT. In KAI in Kota Tua, Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Indonesian Architecture and Planning, ICIAP 2022, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmayanti, K.; Rachmayanti, I.; Wulandari, A.A.A. Revitalization of Kerta Niaga Kota Tua building in Jakarta as a boutique hotel. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Biospheric Harmony Advanced Research, ICOBAR 2020, Jakarta, Indonesia, 23–24 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pratiwi, W.D.; Nagari, B.K.; Nagari, B.K.; Suryani, S. Visitor’s Intentions To Re-visit Reconstructed Public Place In Jakarta Tourism Heritage Riverfront. Alam Cipta 2022, 15, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, F.N.; Herlily. Transit-oriented development principle exploration of Kampung Muka, Ancol, North Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Quality in Research, QiR 2019–2019 International Symposium on Sustainable and Clean Energy, ISSCE 2019, Padang, Indonesia, 7–10 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, S.; Pivac, T.; Ercan, M.A.; Kimic, K.; Ivanova-Radovanova, P.; Gorica, K.; Tolica, E.K. Exploring the Image, Perceived Authenticity, and Perceived Value of Underground Built Heritage (UBH) and Its Role in Motivation to Visit: A Case Study of Five Different Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owojori, O.M.; Okoro, C.S.; Chileshe, N. Current status and emerging trends on the adaptive reuse of buildings: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilly, M.C.; Graham, J.L.; Wolfinbarger, M.F.; Yale, L.J. A Dyadic Study of Interpersonal Information Search. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Horowitz, D. Measuring motivations for online opinion seeking. J. Interact. Advert. 2006, 6, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S. Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) motivations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. A retrospective view of electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Nie, Z. Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model. Land 2022, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Hafeez, S.; Riaz, A. Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction. Int. Res. J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 60, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer Switching Behavior in Service Industries: An Exploratory Study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondan-Cataluña, F.J.; Rosa-Diaz, I.M. Segmenting hotel clients by pricing variables and value for money. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-F.; Jang, S.S. The Effects of Perceived Price and Brand Image on Value and Purchase Intention: Leisure Travelers’ Attitudes Toward Online Hotel Booking. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2007, 15, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G. Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L. Differentiated price loss aversion in destination choice: The effect of tourists’ cultural interest. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Law, R.; Vu, H.Q.; Rong, J. Discovering the hotel selection preferences of Hong Kong inbound travelers using the Choquet Integral. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calver, S.J.; Page, S.J. Enlightened hedonism: Exploring the relationship of service value, visitor knowledge and interest, to visitor enjoyment at heritage attractions. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B. Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, S.; Lee, H. The Effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.; Paddison, B. The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Roldán, J.L. The role of authenticity, experience quality, emotions, and satisfaction in a cultural heritage destination. Authent. Authentication Herit. 2021, 14, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Su, Y.; Su, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L. Perceived Authenticity and Experience Quality in Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Kunqu Opera in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, J.S.A.; Ariffin, A.A.M. The Effects of Local Hospitality, Commercial Hospitality and Experience Quality on Behavioral Intention in Cultural Heritage Tourism. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnawas, I.; Hemsley-Brown, J. Examining the key dimensions of customer experience quality in the hotel industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 833–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Destination attributes influencing Chinese travelers’ perceptions of experience quality and intentions for island tourism: A case of Jeju Island. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, I.P.; Gemar, G. A measure of tourist experience quality: The case of inland tourism in Malaga. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2019, 30, 1466–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Cruz, M. Dimensions and outcomes of experience quality in tourism: The case of Port wine cellars. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Positioning museums on an authenticity continuum. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity in tourism studies: Apres ia lutte. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2007, 32, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Place in Tourist Setting. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly-Boyd, J.M. Existential Authenticity: Place Matters. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplet, M.; Cooper, M. Cultural designs in New Zealand souvenir clothing: The question of authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G. Consuming Heritage Perceived Historical Authenticity. Ann. Tour Res. 2000, 27, 835–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberberg, T. Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of Leisure Class; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, K. Staged authenticity: A grande ide’e? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2007, 32, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P.L. Persisting with authenticity: Gleaning contemporary insights for future tourism studies. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2007, 32, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, P.; Peng, Y. Effect of commercialization on tourists’ perceived authenticity and satisfaction in the cultural heritage tourism context: Case study of Langzhong ancient city. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, V.; Seray, G.G. The effect of perceived authenticity in cultural heritage sites on tourist satisfaction: The moderating role of aesthetic experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyitoğlu, F.; Çakar, K.; Davras, Ö. Motivation, perceived authenticity and satisfaction of tourists visiting the monastery of Mor Hananyo-Mardin, Turkey. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chao, R.-F. How experiential consumption moderates the effects of souvenir authenticity on behavioral intention through perceived value. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. Effects of Authenticity Perception, Hedonics, and Perceived Value on Ceramic Souvenir-Repurchasing Intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xu, J.; Sotiriadis, M.; Shen, S. Authenticity, perceived value and loyalty in marine tourism destinations: The case of Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-K.; Huang, S.-Y. Why visit theme parks? A leisure constraints and perceived authenticity perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskat, B. Perceived quality, authenticity, and price in tourists’ dining experiences: Testing competing models of satisfaction and behavioral intentions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.-H. Effects of ingredients, names and stories about food origins on perceived authenticity and purchase intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.S. The effects of perceived authenticity, information search behaviour, motivation and destination imagery on cultural behavioural intentions of tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Determinants of working holiday makers’ destination loyalty: Uncovering the role of perceived authenticity. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Oh, C.O.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Assessing the economic values of World Heritage Sites and the effects of perceived authenticity on their values. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H.; Sherrell, D.L.; Ridgway, N.M. Consumer Search: An Extended Framework. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Gursoy, D.; Xu, H. Impact of Personality Traits and Involvement on Prior Knowledge. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferns, B.H.; Walls, A. Enduring travel involvement, destination brand equity, and travelers’ visit intentions: A structural model analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Knutson, B.J. An argument for providing authenticity and familiarity in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, A.; Moore, K.; Fisher, D. Experiencing film tourism. Authent. Fellowsh. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, T.; Pandelaere, M.; Van Kerckhove, A. The Amazing Race to India: Prominence in reality television affects destination image and travel intentions. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; McCleary, K.W. Travelers’ Prior Knowledge and its Impact on their Information Search Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifpour, M.; Walters, G.; Ritchie, B.W. Risk perception, prior knowledge, and willingness to travel: Investigating the Australian tourist market’s risk perceptions towards the Middle East. J. Vacat. Mark. 2014, 20, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Takata, K. Relationship between prior knowledge, destination reputation, and loyalty among sport tourists. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; Scott, N.; Wang, Y. Impact of prior knowledge and psychological distance on tourist imagination of a promoted tourism event. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedkin, N.E.; Johnsen, E.C. Social influence networks and opinion change. Adv. Group Process. 1999, 16, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alsheikh, D.H.; Aziz, N.A.; Alsheikh, L.H. Influencing of E-Word-of-Mouth Mediation in Relationships Between Social Influence, Price Value and Habit and Intention to Visit in Saudi Arabia. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Lett. 2022, 10, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Smith, J.R.; Terry, D.J.; Greenslade, J.H.; McKimmie, B.M. Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, R.; Muller, E.; Mahajan, V. Innovation diffusion and new product growth models: A critical review and research directions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X. The impacts of geographic and social influences on review helpfulness perceptions: A social contagion perspective. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104687. [Google Scholar]

- Boto-García, D.; Baños-Pino, J.F. Social influence and bandwagon effects in tourism travel. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 93, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, D.; Ma, E. Perceived value of, and experience with, a World Heritage Site in China—The case of Kaiping Diaolou and villages in China. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-T.H.; Lee, W.-I.; Chen, T.-H. Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: Antecedents and implications. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Gil, I. The concept of value and its dimensions: A tool for analysing tourism experiences. Tour. Rev. 2008, 63, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kwon, J. Green hotel brands in Malaysia: Perceived value, cost, anticipated emotion, and revisit intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1559–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrecht, J. Event Quality, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Behavioural Intentions in an Event Context. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Manzo, J.; Gassiot-Melian, A.; Coromina, L. Perceived value in a UNESCO World Heritage Site: The case of Quito, Ecuador. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Roda, J.; Moral-Cuadra, S.; Aguilar-Rivero, M.; Solano-Sánchez, M.Á. Perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty in a World Heritage Site Alhambra and Generalife (Granada, Spain). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Xie, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S.R. The role of environmental knowledge and interest on perceived value and satisfaction. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 29, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Pu, Y. Impact of cultural heritage rejuvenation experience quality on perceived value, destination affective attachment, and revisiting intention: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanik, J.; Yusuf, M. Effects of perceived value, expectation, visitor management, and visitor satisfaction on revisit intention to Borobudur Temple, Indonesia. J. Heritage Tour. 2022, 17, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Authenticity: Do tourist perceptions of winery experiences affect behavioral intentions? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalimunthe, G.P.; Suryana, Y.; Kartini, D.; Sari, D. The effect of experience quality on behaviour intention: The mediating role of tourists’ perceived value in subak cultural landscape of Bali, Indonesia. Int. J. Bus. Syst. Res. 2022, 16, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulina, A.; Ruslan, B.; Ekasari, R.; Tinggi, S.; Bagasasi, I.A. How Experience Quality, Prior Knowledge and Perceived Value Affect Revisit Intention to Batavia Jakarta. Maj. Ilm. Bijak 2022, 19, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Wolfe, K.; Hodur, N.; Leistritz, F.L. Tourist Word of Mouth and Revisit Intentions to Rural Tourism Destinations: A Case of North Dakota, USA. Int. J. Tour. Research. 2013, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-K. Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: The case of the Korean DMZ. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Chalmers, D.; Wilson, J.; Arshed, N. Would you really recommend it? Antecedents of word-of-mouth in medical tourism. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1975, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Iriobe, O.C.; Abiola-Oke, E. Moderating effect of the use of eWOM on subjective norms, behavioural control and religious tourist revisit intention. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2019, 7, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Joseph, F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle Christian, M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer On Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. In Research Design; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Hatamifar, P. Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, H.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I.A. Exploring the cognitive-affective nature of destination image and the role of psychological factors in its formation. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szromek, A.R.; Hysa, B.; Karasek, A. The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Nayak, J.K. Examining experience quality as the determinant of tourist behavior in niche tourism: An analytical approach. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 15, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Variable Measured | Adapted from |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social demographic | [40] |

| 2 | Electronic word-of-mouth | [112] |

| 3 | Experience Quality | [39] |

| 4 | Perceived Authenticity | [70] |

| 5 | Perceived Price | [35] |

| 6 | Perceived Value | [35] |

| 7 | Prior Knowledge | [113] |

| 8 | Revisit intention | [114] |

| 9 | Social Influence | [40] |

| Sample Characteristic | % | Sample Characteristic | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Education | ||

| Male | 38.4 | Completed year nine or less | 20.94 |

| Female | 61.6 | Completed High school | 48.28 |

| Completed Higher education | 30.79 | ||

| Age | |||

| 15–20 | 27.09 | Relationship Status | |

| 21–25 | 32.02 | Single | 62.07 |

| 26–30 | 13.55 | Married | 35.22 |

| 31–35 | 7.64 | Separated/divorced/widowed | 2.71 |

| 36–40 | 9.11 | ||

| 41–45 | 3.45 | Traveled with | |

| 46–50 | 2.22 | Friends/family/relatives | 89.16 |

| 50+ | 4.93 | Alone | 6.16 |

| Tour group | 4.68 |

| Construct/Item | Mean | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | rho_A | Composite Reliability (CR) | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Price | 0.944 | 0.945 | 0.950 | 0.596 | |||

| PEP1: Museums ticket prices are cheap | 0.600 | 1.784 | |||||

| PEP2: Food prices are affordable | 4.106 | 0.745 | 2.481 | ||||

| PEP3: Souvenir prices are cheap | 3.961 | 0.782 | 2.664 | ||||

| PEP4: The price of renting a vintage bicycle is cheap | 4.155 | 0.777 | 2.624 | ||||

| PEP5: The museum ticket price is in accordance with the services | 4.251 | 0.780 | 2.466 | ||||

| PEP6: Food prices are in accordance with the taste | 4.062 | 0.822 | 3.142 | ||||

| PEP7: Souvenir prices are in accordance with the product quality | 4.096 | 0.802 | 2.901 | ||||

| PEP8: Vintage bicycle renting is in accordance with the rental time | 4.200 | 0.775 | 2.566 | ||||

| PEP9: Food prices can be reached | 4.064 | 0.787 | 2.806 | ||||

| PEP10: The price of renting a vintage bicycle is affordable | 4.148 | 0.763 | 2.709 | ||||

| PEP11: The average museum ticket price is normal | 4.296 | 0.714 | 2.184 | ||||

| PEP12: Food prices are normal | 4.113 | 0.824 | 3.306 | ||||

| PEP13: The price for renting a vintage bicycle is normal | 4.224 | 0.840 | 3.267 | ||||

| Experience Quality | 0.908 | 0.910 | 0.926 | 0.610 | |||

| EXQ1: Adaptive reuse interior design buildings can relieve stress | 4.332 | 0.792 | 2.876 | ||||

| EXQ2: Adaptive reuse architectural design buildings can relieve stress | 4.356 | 0.811 | 3.146 | ||||

| EXQ3: I hope I can get a surprising experience by visiting the Kota Tua Jakarta | 4.425 | 0.768 | 2.342 | ||||

| EXQ4: I hope I can gain valuable experience by visiting Kota Tua Jakarta | 4.438 | 0.767 | 2.475 | ||||

| EXQ5: Kota Tua Jakarta gave me information about history and art | 4.394 | 0.752 | 1.883 | ||||

| EXQ6: Kota Tua Jakarta fueled my interest in history and art | 4.341 | 0.803 | 2.256 | ||||

| EXQ7: I love spending time in Kota Tua Jakarta | 4.281 | 0.805 | 2.610 | ||||

| EXQ8: I love enjoying my relaxing time in Kota Tua Jakarta | 4.352 | 0.745 | 2.242 | ||||

| Prior Knowledge | 0.834 | 0.838 | 0.890 | 0.669 | |||

| PRK1: I already know the public facilities (parking, toilets, mosque) in Kota Tua Jakarta before I visited | 4.057 | 0.848 | 2.262 | ||||

| PRK2: I already knew the restaurants in Kota Tua Jakarta before I visited | 4.064 | 0.856 | 2.404 | ||||

| PRK3: I already know there are tour guides in Kota Tua Jakarta | 3.899 | 0.824 | 1.811 | ||||

| PRK4: I already knew about the ease of transportation in Kota Tua Jakarta before visiting | 4.301 | 0.738 | 1.491 | ||||

| Perceived Authenticity | 0.886 | 0.886 | 0.913 | 0.637 | |||

| PEA1: In my opinion, the museum with adaptive reuse building concept has its own history | 4.474 | 0.778 | 2.027 | ||||

| PEA2: In my opinion, a restaurant/cafe with adaptive reuse building concept has its own history | 4.368 | 0.804 | 2.197 | ||||

| PEA3: In my opinion, the old buildings in Kota Tua Jakarta have been recognized as historic buildings by UNESCO | 4.411 | 0.841 | 2.468 | ||||

| PEA4: In my opinion, the old buildings in Kota Tua Jakarta have been recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO | 4.353 | 0.758 | 1.850 | ||||

| PEA5: In my opinion, the museums in Kota Tua Jakarta have their own past in Jakarta | 4.455 | 0.802 | 2.140 | ||||

| PEA6: In my opinion, adaptive reuse building on restaurants/cafes have their own past in Jakarta | 4.353 | 0.802 | 2.131 | ||||

| Social Influence | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.950 | 0.863 | |||

| SOI1: I would like to visit Kota Tua Jakarta. I have heard about it from family/friends/travel agents. | 4.252 | 0.921 | 3.107 | ||||

| SOI2: I would like to visit Kota Tua Jakarta, which is popular among my family/friends/travel agents | 4.279 | 0.935 | 3.640 | ||||

| SOI3: I would like to visit Kota Tua Jakarta, which has been recommended by family/friends/travel agents. | 4.299 | 0.931 | 3.509 | ||||

| Perceived Value | 0.859 | 0.859 | 0.914 | 0.780 | |||

| PEV1: Kota Tua Jakarta offers good value for the stay | 4.392 | 0.893 | 2.314 | ||||

| PEV2: A stay at a heritage hotel gives the tourist his/her money worth | 4.340 | 0.894 | 2.406 | ||||

| PEV3: The overall expected experience for staying at Kota Tua Jakarta is high | 4.232 | 0.862 | 1.928 | ||||

| Revisit Intention | 0.884 | 0.884 | 0.920 | 0.742 | |||

| REI1: I will be revisiting Kota Tua Jakarta in the future | 4.421 | 0.869 | 2.715 | ||||

| REI2: I have more benefits if I revisit Kota Tua Jakarta | 4.367 | 0.882 | 2.762 | ||||

| REI3: I will come more often to Kota Tua Jakarta | 4.054 | 0.814 | 1.918 | ||||

| REI4: I would recommend Kota Tua Jakarta to family, friends, colleagues | 4.406 | 0.878 | 2.485 | ||||

| Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.858 | 0.861 | 0.899 | 0.640 | |||

| EWM1: I will spread good things about this destination on social media | 4.241 | 0.830 | 2.131 | ||||

| EWM2: I am happy to share my beautiful experience visiting Kota Tua Jakarta on social media | 4.261 | 0.853 | 2.703 | ||||

| EWM3: I will be posting fun pictures/videos about Kota Tua Jakarta on social media | 4.239 | 0.830 | 2.409 | ||||

| EWM4: I will share my beautiful experience on a credible tourism destination site | 3.862 | 0.767 | 1.793 | ||||

| EWM5: I would say positive things about Kota Tua Jakarta to my friends or family via my personal social networks | 4.094 | 0.712 | 1.529 |

| Electronic Word-of-Mouth | Experience Quality | Perceived Authenticity | Perceived Price | Perceived Value | Prior Knowledge | Revisit Intention | Social Influence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.800 | |||||||

| Experience Quality | 0.649 | 0.781 | ||||||

| Perceived Authenticity | 0.649 | 0.740 | 0.798 | |||||

| Perceived Price | 0.688 | 0.687 | 0.673 | 0.787 | ||||

| Perceived Value | 0.672 | 0.700 | 0.691 | 0.660 | 0.883 | |||

| Prior Knowledge | 0.652 | 0.598 | 0.651 | 0.660 | 0.630 | 0.818 | ||

| Revisit Intention | 0.726 | 0.704 | 0.707 | 0.665 | 0.758 | 0.642 | 0.861 | |

| Social Influence | 0.639 | 0.610 | 0.656 | 0.598 | 0.632 | 0.594 | 0.677 | 0.929 |

| Hypothesis | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| H1: Perceived Price -> Revisit Intention | 0.081 | 0.080 | 0.053 | 1.521 | 0.064 | Rejected |

| H2: Experience Quality -> Revisit Intention | 0.151 | 0.159 | 0.061 | 2.470 | 0.007 | Accepted |

| H3: Perceived Authenticity -> Revisit Intention | 0.123 | 0.122 | 0.067 | 1.821 | 0.035 | Rejected |

| H4: Prior Knowledge -> Revisit Intention | 0.097 | 0.099 | 0.044 | 2.171 | 0.015 | Accepted |

| H5: Social Influence -> Revisit Intention | 0.185 | 0.184 | 0.043 | 4.275 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H6: Perceived Value -> Revisit Intention | 0.336 | 0.328 | 0.056 | 5.976 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||

| H7a: Perceived Price -> Perceived Value -> Revisit Intention | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.022 | 2.348 | 0.010 | Accepted |

| H7b: Experience Quality -> Perceived Value -> Revisit Intention | 0.090 | 0.087 | 0.029 | 3.121 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H7c: Perceived Authenticity -> Perceived Value -> Revisit Intention | 0.060 | 0.058 | 0.028 | 2.164 | 0.015 | Accepted |

| H7d: Prior Knowledge -> Perceived Value -> Revisit Intention | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.022 | 2.353 | 0.010 | Accepted |

| H7e: Social Influence -> Perceived Value -> Revisit Intention | 0.056 | 0.054 | 0.022 | 2.567 | 0.005 | Accepted |

| H8a: Perceived Price -> Perceived Value -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.020 | 2.165 | 0.015 | Accepted |

| H8b: Experience Quality -> Perceived Value -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.027 | 2.862 | 0.002 | Accepted |

| H8c: Perceived Authenticity -> Perceived Value -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.024 | 2.187 | 0.015 | Accepted |

| H8d: Prior Knowledge -> Perceived Value -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.019 | 2.251 | 0.012 | Accepted |

| H8e: Social Influence -> Perceived Value -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.021 | 2.288 | 0.011 | Accepted |

| H9a: Perceived Price -> Revisit Intention -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.029 | 1.396 | 0.082 | Rejected |

| H9b: Experience Quality -> Revisit Intention -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.077 | 0.081 | 0.033 | 2.354 | 0.009 | Accepted |

| H9c: Perceived Authenticity -> Revisit Intention -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.062 | 0.062 | 0.034 | 1.814 | 0.035 | Rejected |

| H9d: Prior Knowledge -> Revisit Intention -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.023 | 2.130 | 0.017 | Accepted |

| H9e: Social Influence -> Revisit Intention -> Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.025 | 3.741 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| R2 Adjusted Value | Q2 Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Word-of-Mouth | 0.559 | 0.350 |

| Perceived Value | 0.610 | 0.469 |

| Revisit Intention | 0.685 | 0.500 |

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | Threshold Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.058 | 0.066 | Between 0 to 1 |

| NFI | 0.776 | 0.772 | >0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maulina, A.; Sukoco, I.; Hermanto, B.; Kostini, N. Tourists’ Revisit Intention and Electronic Word-of-Mouth at Adaptive Reuse Building in Batavia Jakarta Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914227

Maulina A, Sukoco I, Hermanto B, Kostini N. Tourists’ Revisit Intention and Electronic Word-of-Mouth at Adaptive Reuse Building in Batavia Jakarta Heritage. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914227

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaulina, Anita, Iwan Sukoco, Bambang Hermanto, and Nenden Kostini. 2023. "Tourists’ Revisit Intention and Electronic Word-of-Mouth at Adaptive Reuse Building in Batavia Jakarta Heritage" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914227