Abstract

This qualitative study evaluated a training intervention aimed at increasing the personal development curves of the ABC company’s white-collar employees and developing presentation preparation techniques. The participants prepared presentations using the 10/20/70 learning rule for the competencies they identified. After academicians and business managers evaluated the presentations, semi-structured one-on-one interviews were conducted to identify the intervention’s benefits and limitations. The eight participants, who were white-collar professionals from the ABC company, were identified using non-probabilistic purposive sampling and interviewed online for about 30 min using Microsoft Teams. The interviews were audio recorded. The Maxqda-2022 program was used to examine the interview data. The analysis showed that the participants had negative feelings about the performance process based on their personal development competencies, particularly regarding process management. They also mentioned having the opportunity to learn through experience and conducting interviews. The participants agreed that their organizations should increase their development awareness and conduct 360-degree evaluations. They also said that intensive practical training at universities was needed because they felt their undergraduate education had not changed their perspectives or prepared them for a career.

1. Introduction

Businesses must adapt to the changing world. In particular, it is critical to develop and retain a creative and talented workforce to gain a sustainable competitive advantage in the digital age. The innovation activity of enterprises that achieve sustainability involves not only the release of new products or services but also constant changes within the organization [1]. The key to achieving social sustainability is human development, including education, training, a positive work environment, fair pay, and a sound corporate culture [2]. Since employee performance determines a business’s success or failure, managers pay more and more attention to investing in employee training and development. This highlights the importance of investing in learning to improve organizational performance [3]. Employee performance and commitment to the business can be increased by various motivating factors, such as organizing programs to meet the needs of the employees, creating reward and incentive mechanisms, and creating training opportunities. According to the modern management approach, for the workforce to be efficient and effective, it is necessary to perceive the employee as a person who wishes to satisfy needs and meet expectations, not as a machine [4]. Hence, it is necessary to train employees to improve their performance. Employee performance and job satisfaction are powerful tools for continuously developing and improving organizational performance to achieve strategic objectives [5].

Although for years a good wage policy has been one of the strategies used to improve employee performance and increase the organization’s competitiveness, it is no longer a sufficient element on its own. For instance, Vincent (2020) [6] stated that training makes employees feel like they are a part of that institution, awakens a sense of belonging in all employees, creates professional development, and improves the employees’ skills while providing a knowledgeable workforce that makes fewer mistakes. ABC is one of the companies that say, “Our employees are our most valuable asset”. Accordingly, the company, which understands the importance of human capital, approached academics from Manisa Celal Bayar University to support its efforts to invest in this capital.

The intervention involved white-collar employees preparing a presentation about improving themselves in the competencies they identified according to the 10/20/70 learning rule. After the presentations had been evaluated by academicians and business managers, one-on-one interviews were conducted with the participants to reveal the benefits and deficiencies of the study. The intervention was important for these white-collar employees because the evaluations involved academicians and the employees’ presentations contributed to their annual performance review.

The purpose of the study is to increase the personal development curves of white-collar employees and develop their presentation preparation techniques. In doing so, it also addresses the lack of research about personal development and informal learning techniques in Turkey and beyond. Finally, through co-operation between a university and a company, the study can contribute to both the academic literature and the business world.

This paper has four parts. The first part introduces the classification of employees. The second part discusses the effects of employee training and development on business performance. The third part reviews the literature about the 70/20/10 learning model. The fourth part presents and discusses the results.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Classification of Employees

The previous literature classifies employees into two main groups [7,8], white-collar and blue-collar, which often define the working class based on inequalities between workplaces. White-collar personnel in senior management play important roles in making strategic and long-term decisions. In middle management, white-collar personnel are involved in making medium-term decisions, while lower-level management makes short-term, daily, weekly, monthly, or annual decisions about repetitive and routine work [9]. White-collar workers do not engage in “more physically demanding” activities but are often better paid than blue-collar workers who perform manual labor [10]. Traditionally, these workers were referred to as “white collar” because they were more likely to wear white collars. A blue-collar worker is defined as someone who performs more physical labor, such as manufacturing, mining, mechanical engineering, repair, and technological applications [10]. The main focus of this study is white-collar employees from the white-collar company, ABC, who volunteered to participate in order to increase their personal development curves using the 10/20/70 learning model within the framework of their own competencies.

2.2. Sustainable Employability

Sustainability has become a key issue in recent years. According to the United Nations, sustainable development requires an integrated approach that takes into consideration environmental concerns along with economic development (https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability (accessed on 12 December 2020). A significant part of the economic development of developed countries is based on production [11]. However, increased production creates problems due to higher energy consumption and carbon emissions, and exploitation of natural, social, and human resources in organizations. Therefore, sustainability has become associated with a broader range of issues, including economic and social elements [12].

Employability, the first aspect of labor participation, refers to an individual’s ability to adequately perform work in their current and future jobs [13]. According to the British Industry, employability means that the individual possesses the qualities and competencies required to meet the changing needs of employers and customers and thereby realize their own aspirations and potential in work [14]. Sustainable employability refers to the extent to which workers are able and willing to remain working now and in the future [12]. To enhance sustainable labor participation it is important to understand the factors that contribute to workers’ employability, vitality, and work ability. One important factor that can contribute to sustainable employability is employee development and training, which create bonds between organizations and employees.

As in most professions, businesses have expectations for continuing education, learning, and careers so that employees can maintain their current positions and continue their development. Therefore, people pursue self-development strategies that allow them to perform their current jobs well while creating and maximizing opportunities for future employment [15].

2.3. Employee Development, Training, and Effects on Performance

Many businesses strive to develop their employees because this investment is vital to maintain and develop the skills, knowledge, and abilities of both individual employees and the organization as a whole [16]. Given the ever-changing needs of individuals and organizations, personal development offers a promising strategy to train employees and managers [17]. Hence, one of the most important functions of an enterprise’s human resources department is to encourage employee development: the more employees develop, the more satisfied they are with their jobs and the more committed they will be to their jobs, which in turn will improve their performance, thereby enabling the organization to function more effectively [18]. The situation is similar regarding employee training. Employee training refers to an organization’s planned attempt to facilitate employees’ learning of work-related knowledge, skills, and behaviors [19] or the acquisition and development of knowledge, skills, and attitudes so that employees can perform their jobs effectively [20]. Businesses that aim to gain a competitive advantage realize the importance of training for improving employee performance. Empirical studies have demonstrated the positive effect of employee training on organizational performance [21]. Ideally, the more employees are trained and the more satisfied they are with their jobs and environmental conditions, the more they can help improve their organization’s performance. Here, organizational performance shows how effectively and efficiently managers use corporate resources to satisfy customers and achieve corporate goals and objectives [20].

Hameed and Waheed (2011) [18] identify two focuses of employee development: personal development and self-learning. These concepts show that employee development should be recognized by employees who are willing to learn. Hence, the effectiveness of workplace learning is closely linked to the effectiveness of learning types.

Learning can be divided into two types: formal and informal. Formal learning is structured learning outside the work environment, i.e., ‘out of work’, usually in classroom-based formal education settings. This type of learning mostly consists of planned learning activities to help individuals acquire the specific knowledge, awareness, and skills needed for doing their jobs well [22]. Informal learning generally describes any learning that does not involve a formally organized learning program or activity [23]. It can be conceptualized according to four organizing principles: occurring outside classroom-based formal education environments; involving either intentional or incidental learning; being based on practice and judgment; and learning through mentoring and teamwork. Informal learning tends to be considered more important and effective, and therefore ‘superior’ to formal classroom-based learning [3]. This suggests that the choice of learning strategy is critical to job performance, with informal learning being of particular importance [24]. In the present study, the ABC company selected a competency area from the organization’s white-collar employees to develop those skills open to development through self-learning, i.e., the informal learning method, using the 10/20/70 model.

A number of studies have evaluated the contribution of employee development to businesses. Iamsomboon et al. (2018) [25] found that organizational training not only increases employees’ knowledge and skills but also raises employee satisfaction, innovation, and productivity. Similarly, Vincent (2020) reported that training makes employees feel that they are a part of the organization, creates a sense of belonging, improves their skills, enables professional development, and creates a knowledgeable workforce that makes fewer mistakes [6]. Hot (2017) [4] determined that there is a linear relationship between increased training and employee and organizational performance. More specifically, training increases employees’ awareness, self-confidence, job satisfaction, professional knowledge, skills, and competencies. This personal development of the employees in turn improves their performance. The findings showed that, in order to increase organizational performance, businesses must prioritize many kinds of activities to develop human resources, especially education.

Other studies have identified the skills needed for white-collar employees. Özsoy and Gürbüzoğlu (2019) [26] found that those responsible for recruiting white-collar employees state that white-collar employee or employee candidates should possess communication skills, be knowledgeable, positive, honest, self-confident, show perceptiveness, and work in harmony with others. However, Özsoy and Gürbüzoğlu also underlined that more studies are needed on the specific skills required in white-collar workers, and recommended drawing on qualitative as well as quantitative methods. Waner (1995) found that both academics and professionals suggest that work-related writing skills, oral and interpersonal skills, basic English skills, and other communication skills are important for white-collar employees [27]. Hence, to attract job seekers, employers should at least offer training and development opportunities, even if they cannot offer secure long-term job opportunities [28].

Along with training, employee retention has become an important issue for businesses. Businesses that invest in employee training should also strive not to lose their employees. Mutanga et al. (2020) identified the various factors that either attract employees to stay or force them to leave an employer [29]. The former include good pay, job security, flexibility, advantages, productive working conditions, mental challenges in the job, and growth and promotion prospects. The latter include low wages, a bad management style, bad working conditions, weak interpersonal relations due to the poor work environment and management style, lack of recognition, and lack of career opportunities [29]. Training and development programs can help improve interpersonal relations.

The present study evaluates an intervention conducted with the ABC company to promote employee development based on an informal learning model. This study investigated what kind of contributions this learning model can make to white-collar employees within the 10/20/70 framework. Many studies have noted the inadequacy of studies on this subject [19,20,22,26]. Hence, the present study can help determine the direction in which the forms of employee development will evolve. Mikolajczyk (2022) [30] underlined that employee development issues require further research, especially regarding the increasingly common hybrid work model. Given the lack of similar research in the literature and the lack of studies focused on the personal development and presentation skills of white-collar workers, this study makes an important contribution to the literature.

2.4. 10/20/70 Learning Rule

Since the 1990s, the interest of both academic researchers and business leaders in individual learning practices in institutions has shifted from formal learning to informal [31]. According to the 10/20/70 learning rule, a popular version of informal learning, 70% of learning stems from work experiences, 20% through relationships, and 10% through formal education [32]. The 10/20/70 framework is based on empirical research conducted in 1988 covering four separate studies of over 200 successful executives from six large companies. The findings indicated that 70% of a manager’s learning comes from challenging work experiences, 20% from relationships with other people and their own supervisors, and the remaining 10% through formal training [33]. The findings from the few other studies that have investigated this rule suggest that it helps by increasing the emphasis on on-the-job experience, while its use in coaching and mentoring programs supports real-time, on-the-job development, especially as work experiences emerge [34]. Similarly, Johnson et al. (2018) [33] conclude that the 10/20/70 framework can better guide talent development success through improved learning transfer in the public sector. However, they noted that this will only happen if future practice focuses on both the types of learning required and how to integrate them meaningfully. Based on empirical data, Zeman (2022), on the other hand, concluded that the 10/20/70 learning model is not a one-size-fits-all approach, given the impact of culture. Rather, the model can be adapted to 50/30/20 [35].

3. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted with a private company (named ABC for this study), which is the largest battery manufacturer and seller in Turkey, with three factories in Manisa and 1000 employees. This company was chosen because its management wanted an academic evaluation of a project conducted within the company. Data were collected through online interviews of about 30 min with eight white-collar employees.

The intervention conducted in the present study aimed to increase the development curves of white-collar employees and develop their presentation techniques. The participating employees were asked to identify, research, and experience a personal development topic in their daily lives. They then shared the related process with their managers using a presentation program, thereby improving their presentation skills. The employees used informal learning and experienced what they learned. The study was conducted after receiving the approval of the ethics committee of Manisa Celal Bayar University.

3.1. Research Design

The participating white-collar employees at the ABC company uploaded the presentations they prepared regarding their performance evaluation to an online platform chosen by the company. The participants identified their personal development competencies at those points where they were open to development. The following points were identified: project management, persuasion and negotiation, suggestion development and innovation, team achievement, customer focus, analysis and interpretation, ensuring the visibility of projects, continuous development, reporting and documentation, relationship management, good communication, strategic direction unity, management with systems and processes, developing and motivating the team, establishing the detail-whole relationship, customer orientation, analysis and interpretation, solution orientation, learning and curiosity, co-operation between teams, ability to work with contrasting personalities, documentation, managing change, planning, suggestion development, and innovation. Competency targets were determined for the following subjects: lean thinking, stock management process, problem solving, experiencing different sales channels, being us, owning your business, strategic perspective, resource management, and continuous improvement.

Due to technical problems, the video recordings of the presentations during the project preparation were uploaded only as PowerPoint presentations. Therefore, the reviewers gave evaluation scores based only on these presentations. However, this technical problem did not affect the research process. The presentations were rated anonymously in terms of the four criteria below:

- The employee has used the different research resources related to the development area and conveyed the obtained information clearly (0–4 points);

- The participant has tried to apply the obtained knowledge in practice and convey the positive and negative results of their experiences (0–7 points);

- The employee has planned the introduction, main message, and conclusion sections effectively and shared them in the appropriate order (0–4 points);

- Academician feedback.

A total of 167 presentations were uploaded to the system and evaluated. The academicians’ evaluations constituted 15% of the total evaluation score. The presentations received overall scores as follows:

- A score of 0% if the presentation was not prepared;

- A score of 50% if the presentation was prepared but not sent to human resources;

- A score of 70% if the presentation was sent to human resources by 30 November;

- A score of 71–90% if the presentation scored 10–20 in the evaluation;

- A score of 91–100% if the presentation scored between 21–30 in the evaluation;

3.2. Hypothesis and Methods

After the presentations were evaluated by the business managers and academicians using the criteria outlined above, one-to-one interviews were conducted to collect the participants’ views on the benefits and deficiencies of the performance evaluation intervention. It is foreseen that the research will contribute to the employee’s personal development and professional skills and increase the company’s performance in the long term.

More specifically, the interviews, which had six open-ended questions and one demographic question, aimed to identify what both businesses and universities that educate future business personnel can do to improve employees’ personal development and presentation skills. Some question examples are presented below.

- How many years have you been working in this company and in which position do you work?

- What were the factors that affected you positively in your personal development goal?

- What can you do as an employee to increase your personal development?

- What can the company do differently to increase personal development?

The study addressed the research gap by first exploring how to increase the personal development curves of white-collar employees of the ABC company. Through the questionnaires, the study addressed the following four research questions:

- RQ1:

- What are the employees’ perceptions regarding the positive and negative sides of personal development?

- RQ2:

- Was the 10/20/70 learning model used effectively? And if so, in what respects?

- RQ3:

- What are the employees’ expectations of the company and what can an employee do for their personal development?

- RQ4:

- How have the employees’ university education experiences contributed to their working lives? What do they think should be done differently in university education processes?

To address these research questions, the participants responded to semi-structured questions about the process of making personal development goals and their evaluations of the education and training they received while at university. In this qualitative research study, semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. This is an exploratory interview technique most commonly used in social sciences for qualitative research purposes or to collect clinical data [36]. Semi-structured interviews have become an increasingly popular method, as their flexibility and versatility allow the interviewer to gain deeper answers to questions. The questionnaire focused on the topics that both the academicians and business managers wanted to learn about. It was also based on the literature review, particularly recent studies on employee training and its effects on performance and retention. The aim was to learn how to increase the development curves of white-collar employees.

The participants were determined using non-probabilistic purposive sampling. In this method, the researcher selects participants that they believe can help provide answers to the research problem [37]. For this reason, “purposive sampling” is used more than “probability-based” sampling in qualitative research [38]. Qualitative studies should be evaluated according to how well they meet the goals and objectives related to the subject and the suitability of the units in the sample [39]. Considering these characteristics of the sampling subject in qualitative research methods, white-collar employees were selected who could give the best answers to the interview questions. Video-recorded interviews lasting about 30 min were conducted on 30–31 May 2022 with eight white-collar employees who were experts in their fields. Table 1 lists the participants’ characteristics. The names and exact units are not given to maintain confidentiality. In the following sections, the participants are referred to by the codes assigned for each in Table 1. The recorded data were transcribed and analyzed with the Maxqda-2022 program.

Table 1.

Participants’ information.

The participants were first asked about their areas of expertise, how many years they have been working in the business, which personal development goal they chose, and whether they used the 70/20/10 learning model. For the analysis, the statements about length of employment and gender were compared and interpreted according to the cross tables. Length of employment varied between 2 and 15 years, and all participants except one had used the 70/20/10 model.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

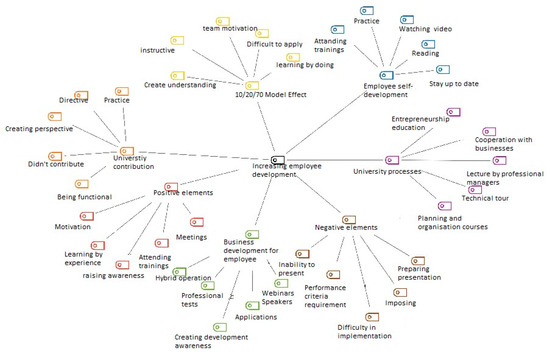

In qualitative research, the analysis process begins at the data collection stage [40]. After the interview recordings had been transcribed, coding began with the codes prepared on the basis of the themes in the data. Two researchers conducted the coding separately before reaching a joint decision with the other researchers to clarify and finalize the codes. Using the expressions given by the semi-structured questions, the researchers labeled the code without changing the expressions of the participants. As well as the codes prepared based on the literature, a number of unexpected codes emerged from the data, which required generating new codes from the common expressions of the participants. Figure 1 shows the code hierarchy formed after the analysis.

Figure 1.

Code hierarchy.

The following themes emerged from the semi-structured questionnaire responses: the positive and negative elements of the performance process, according to the company, to increase white-collar employees’ personal development competencies; what the company can do to promote employee development; what employees can do to promote their own development; the effects of the 10/20/70 model; and the effects of university education. The effects of university education were shaped as a contribution to their careers and what they needed in their university programs.

The semi-structured questions identified our themes and categorization while the participants’ responses helped us to group similar words and phrases. An open coding process was used in this research. In open coding, the researcher identifies distinct concepts and themes for categorization [41] (Williams, Moser, 2019). In this approach, the codes somehow impose themselves on the researcher as a result of analyzing and checking data [30] (Mikołajczyk, 2021).

The participants were first asked to identify the positive and negative elements of the performance process. Regarding the positive elements theme, participants gave similar responses, including motivation, learning by experience, raising awareness, and attending training sessions and meetings. The researchers assigned these words or phrases as positive codes. Regarding the negative elements theme, the participants’ responses included inability to present, performance criteria requirement, difficulty to implement, and imposing and preparing presentations, which constituted negative codes.

The third question asked the participants to identify what the company can do to promote employee development. The researchers categorized this theme as business development for employees. Frequent responses included hybrid operations, professional tests, applications, creating development awareness, webinars, and speakers.

The fourth question asked what employees can do to promote their own development, and was categorized as the theme of employee self-development. Common responses were attending training sessions, practicing, reading watching videos, and keeping up to date.

The fifth question concerned the effects of the 10/20/70 model. Under this theme, participants mentioned phrases like difficult to apply, team motivation, learning by doing, instructive, and creating understanding. The last two questions concerned university processes and the contribution of university education to the participant’s career. Responses like planning and organization, technical tours, and lecturing from professional managers were coded under the university processes theme, while phrases like being functional, contribution, creating perspective, directive, and practice were coded under the university contribution theme. The descriptive representation of the themes and codes was detailed under sub-headings.

3.4. Results

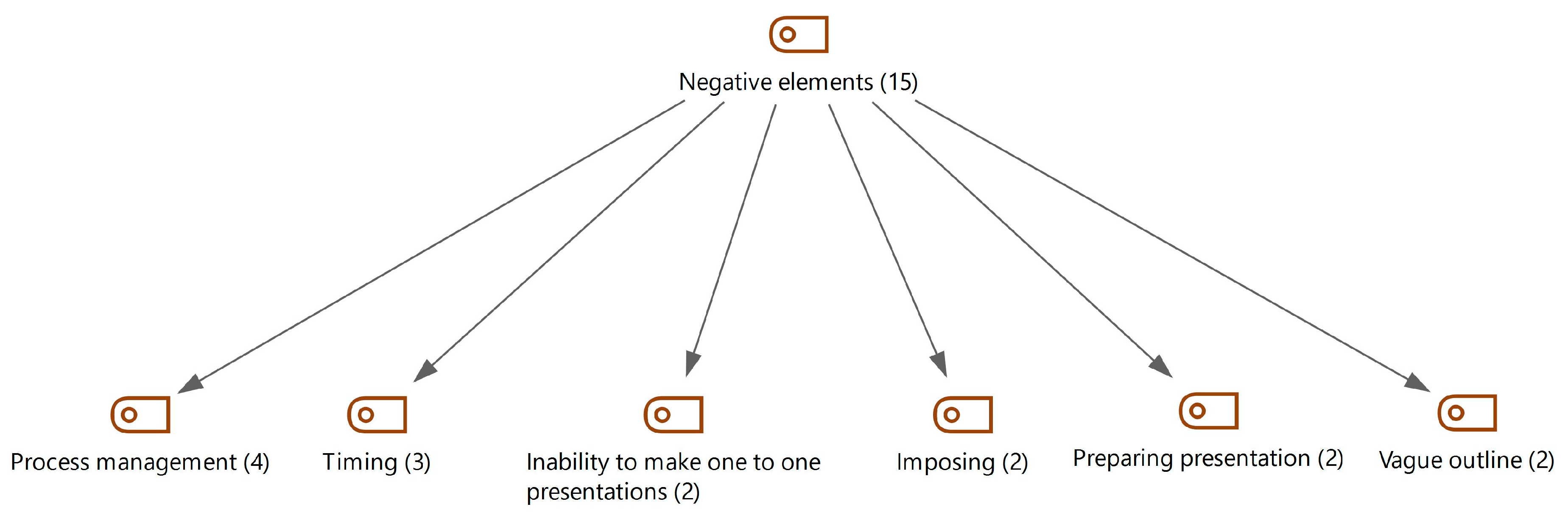

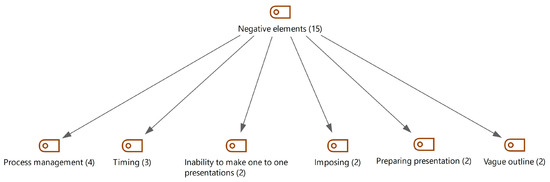

3.4.1. Negative Elements

The participants expressed negative views about the following elements of the performance process: process management (20%), timing (15%), preparing a presentation (10%), being unable to give one-on-one presentations (10%), imposition (10%), unclear draft (10%), lack of feedback (5%), necessity of performance criteria (5%), difficulty in implementing the target (5%), lack of timely feedback (5%), and stress (5%). The participants were particularly critical of the management of the process. Some of the examples of participant’’ quotations are given below:

G5: “When we look at the process in general, the delivery time, form and follow-up part could have been managed a little better. It would be more effective if. We could benefit more”.

G8: “I think the application part should be checked and even questioned a little more. For example, it could be: participants could make presentations to department managers”.

Similarly, the participants expressed intense negativity about timing. They also stated that they did not know how to make a presentation and that the process had been imposed.

G5: “Homework was given too late. Since it was given late, after the summer came, most people went on leave. Therefore, the follow-up was not done very well”.

G8: “This is my opinion, it may be very utopian, but it should not be like an imposition. If it is forced like you will do it and there is no curiosity, if there is no enthusiasm for self-improvement, then it is persecution”.

Figure 2 shows the negative elements in performance process.

Figure 2.

Negative elements in performance process.

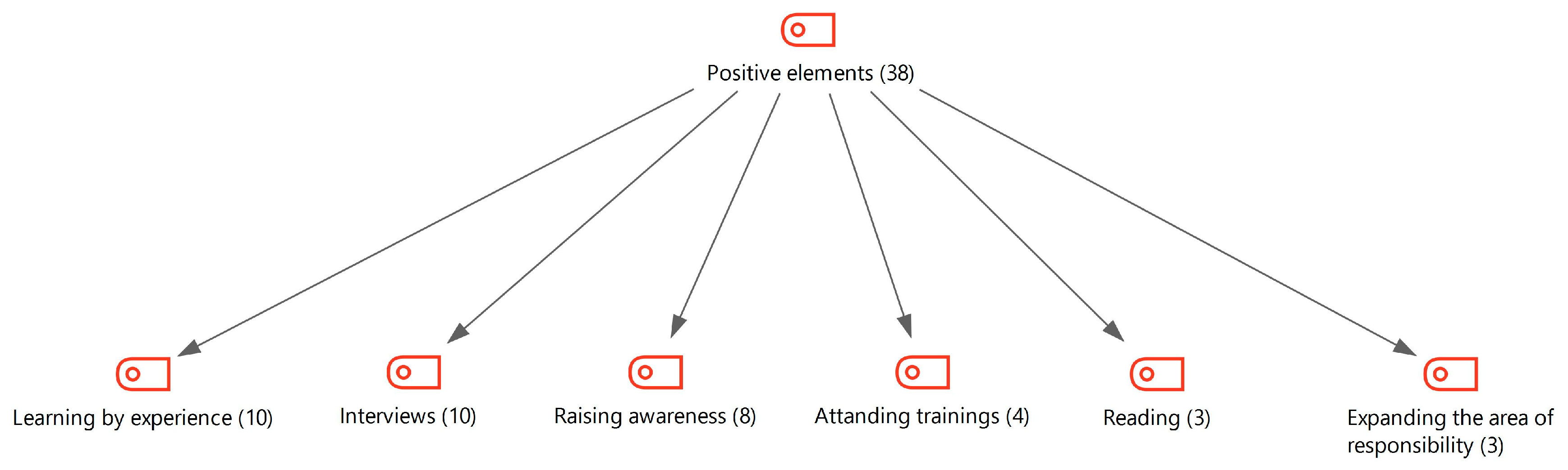

3.4.2. Positive Elements

Some participants stated that the performance process gave them an opportunity to learn and gain more experience. They also made positive comments about mentoring, one-on-one interviews, and receiving feedback. The performance process raised their awareness, which encouraged them to participate in the training sessions, read books, and expand their areas of responsibility. They saw the process as a positive motivation-enhancing element that allowed them to remember and reinforce their presentation skills.

G3: “I attended meetings. I did some work. I found that learning by experience is more beneficial”.

G6: “For the first time, I was able to find and develop methods on my own with what I read, listen to, or watch”.

Figure 3 shows the positive elements in performance process.

Figure 3.

Positive elements in the performance process.

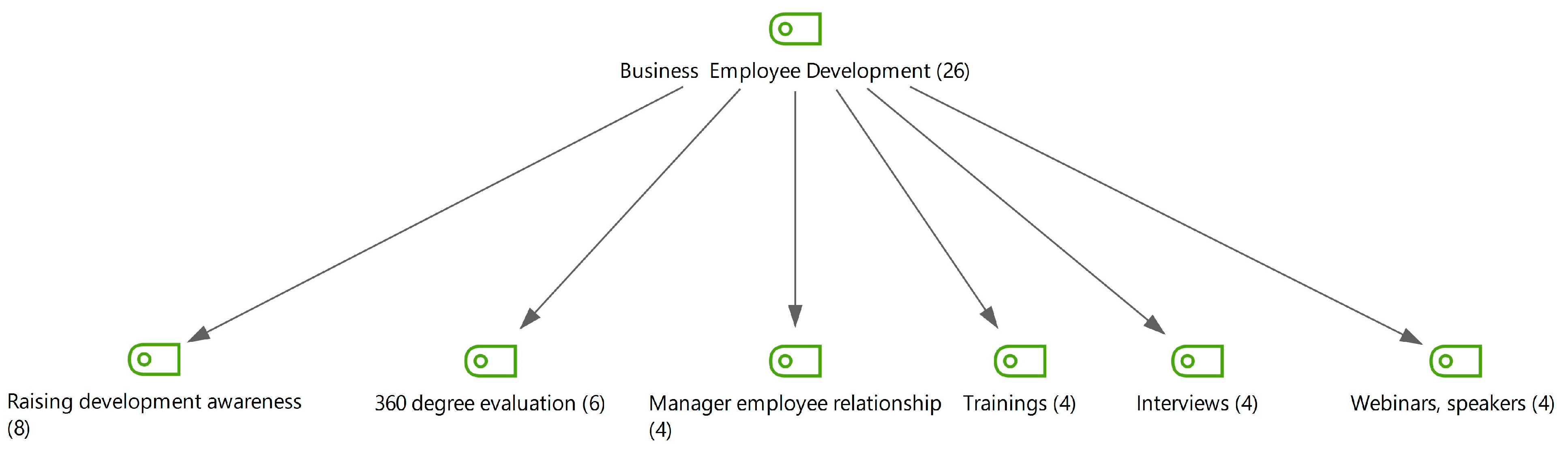

3.4.3. Employee Development

Regarding the participants’ views about what their company could do differently to promote employee development, a number of participants recommended creating development awareness. They also suggested regular use of 360-degree evaluations, holding webinars, inviting speakers, conducting professional employee tests and satisfaction surveys, and introducing a hybrid working model, albeit at low intensity.

These views are exemplified in the following statements:

G1: “I think that, with certain studies, businesses can direct the development areas of their employees and the areas they need to focus on. So they can do this work in a more concrete way”.

G8: “If an employee or an individual has a curiosity for learning, if there is a curiosity and passion that we call baby curiosity, then you do not need to impose anything. The employee already needs it. I think the key word is need. The employee should say that I need this personal development”.

G4: “We can solve this in a very short time, even within the company, but the desire and enthusiasm for self-development must be created in people”.

G5: “I aim to increase efficiency there as much as possible. I think it is important to make a 360-degree evaluation at a certain period”.

As can be seen, some participants suggested that the company should direct its employees towards those points that are open to improvement, which can sometimes be done through challenging targets. Hence, the participants stressed the need for conducting 360-degree evaluations. Thus, these employees contradict the negative view expressed in the previous theme that the process is an imposition.

Figure 4 shows the company actions to promote employee development.

Figure 4.

Company actions to promote employee development.

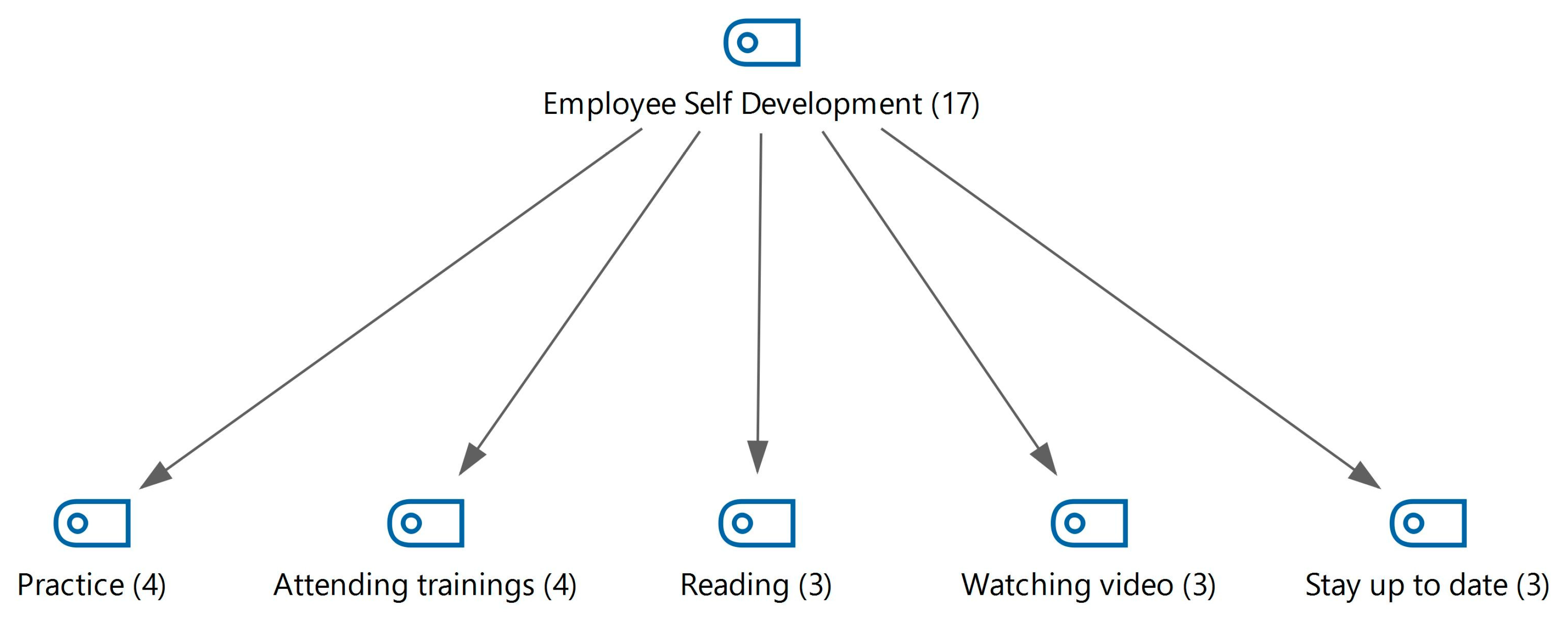

3.4.4. Employee Self-Development

The participants stated that they mostly attended company training sessions for their own development, practiced their goals, read books, particularly those suggested by their trainers or consultants, and watched related videos or movies. The following quotations exemplify these views:

G5: “There are publishers recommended by our instructor at the leadership academy. I try to follow their broadcasts”.

G7: “From the books, the things I watched, the feedback, the mentorship I received, I always progressed by listening to such stories or by exemplifying something that someone else had experienced in my head. But from now on, it’s a serious opportunity for me to really practice. If you ask what you are doing, in short, I can say that I transform from theory to practice and live”.

Figure 5 shows employee self-development elements.

Figure 5.

Employee self-development.

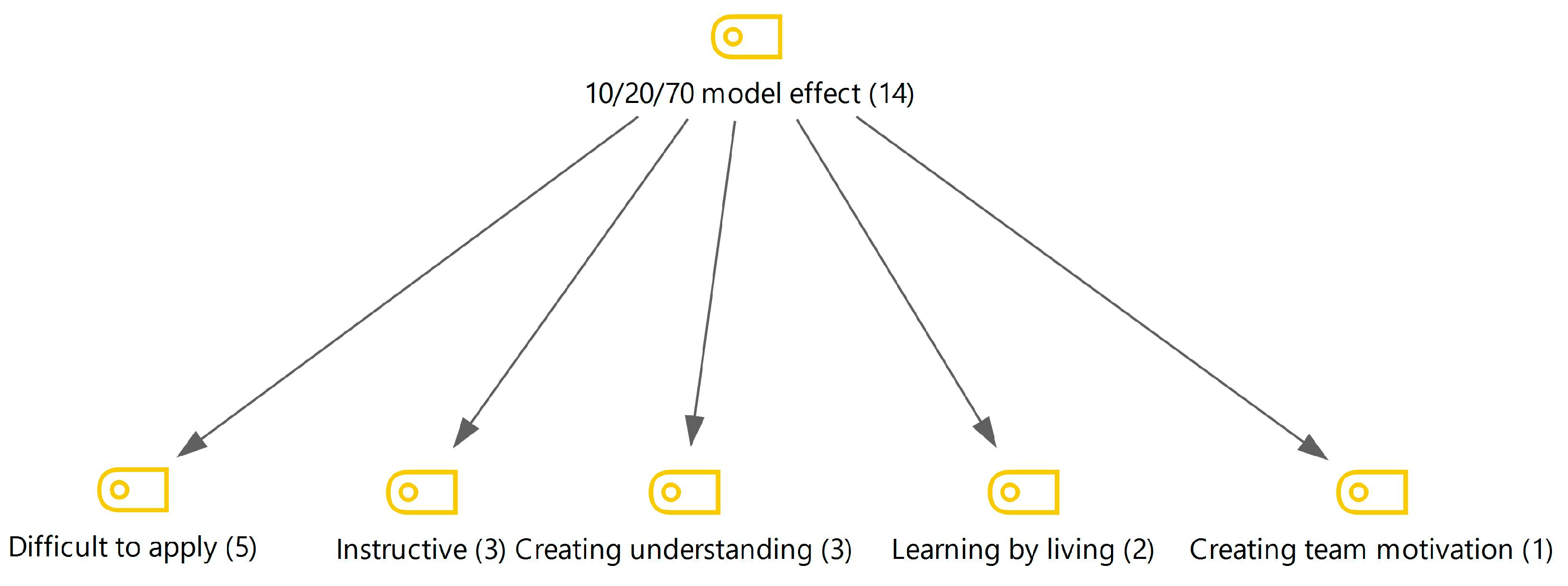

3.4.5. The 10/20/70 Rule

Participants were asked whether they applied the 10/20/70 rule, which is an informal learning model that the company wanted its employees to use while fulfilling their personal development goals, and whether it is effective. The participants who answered this question stated that it was difficult to apply the model. On the other hand, they found that the model created moderate understanding and was instructive. Some participants explained that the model was effective in learning by experience and providing team motivation.

G7: “I got mentoring from our general manager, but 70 percent of the job is really a process. It is very difficult to say that I have completed 100 percent, but I think that the first 30 percent is an indication that you can climb that hill”.

Figure 6 shows employee self-development elements.

Figure 6.

The 10/20/70 rule effects.

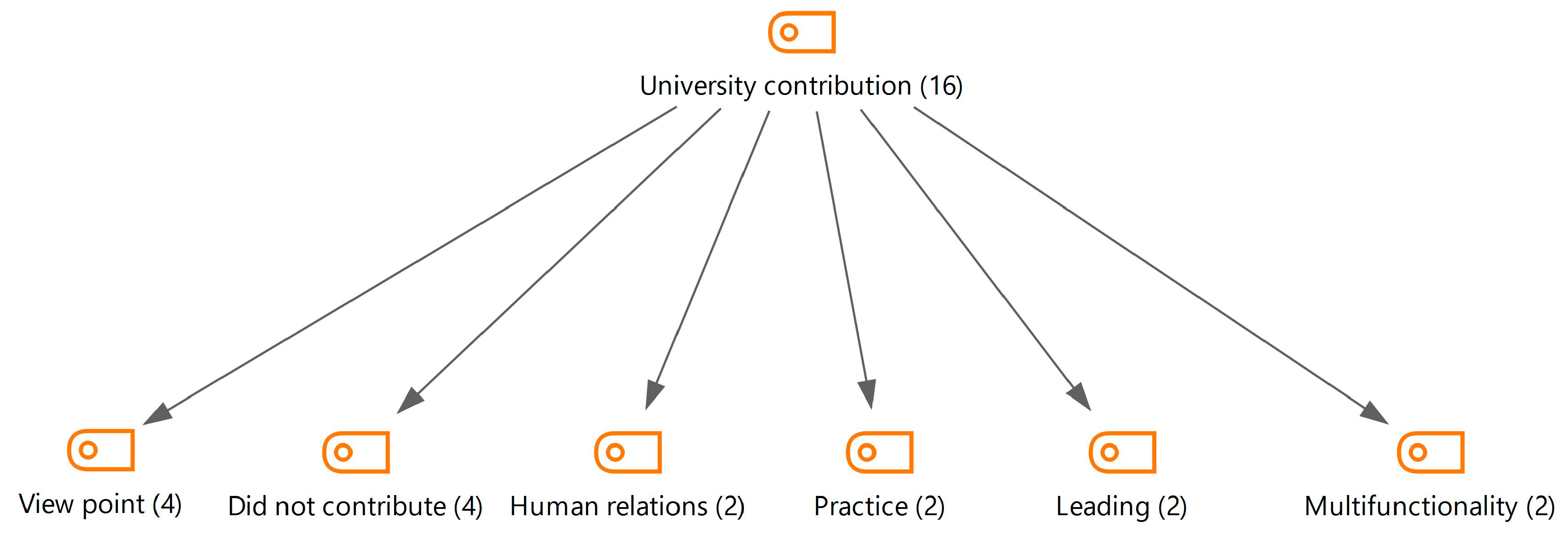

3.4.6. University Contribution and Processes

Most participants stated their university education did not contribute heavily to development or create a perspective about life. On the other hand, some participants stated that the university experience is a guide, develops human relations, adds functionality, and gives students a chance to practice.

G2: “It contributed a point of view. Technically I’m not using anything right now”.

G1: “Due to my department, I have to look very analytically because I am a mathematician. Therefore, it contributed a lot in that respect. The university had an impact on me in analyzing numerical data, processing, programming, relatively resource management”.

Figure 7.

University effects.

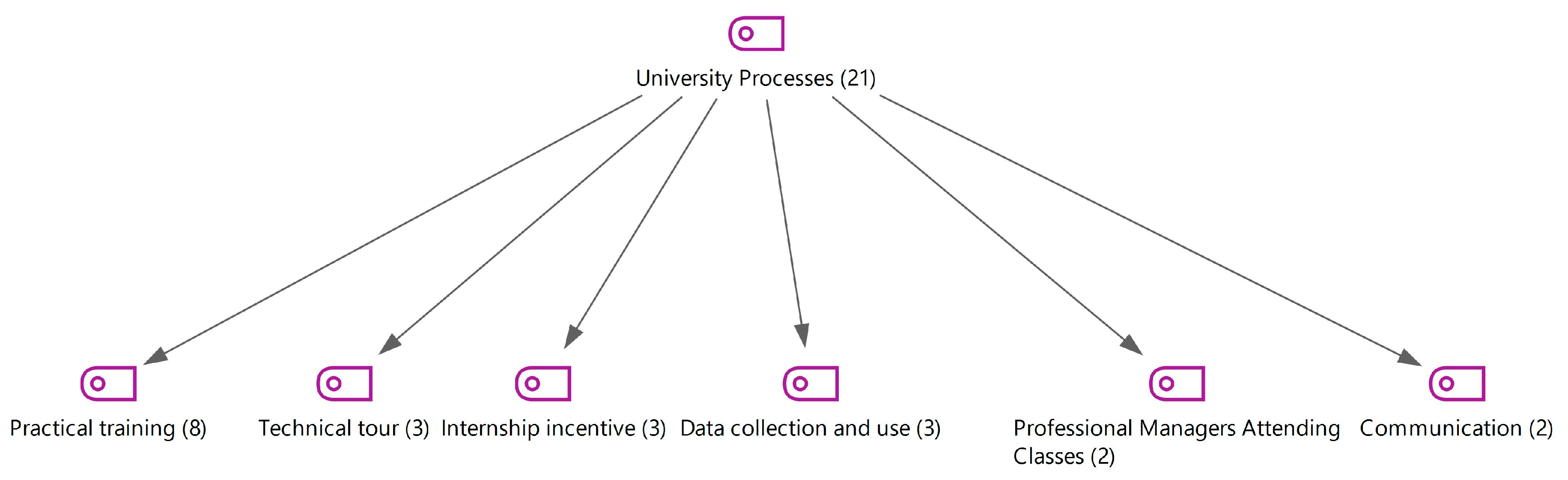

Figure 8.

University processes.

Regarding what universities should do differently, the participants most frequently recommended practical training. In addition, they suggested educational innovations for data collection and use and organizing technical trips to see how applications are implemented. They also recommended inviting professional managers to university courses, preparing presentations, and communication lessons. A few participants mentioned having better-equipped trainers, co-operation with businesses, entrepreneurship, planning and organization, and foreign language courses.

G3: “Training should be given mainly on preparing presentations based on data. We are experiencing this problem especially for new engineering colleagues”.

G5: “For example, when most engineers enter a factory, they are given a team management job. When I started this job in this factory, there were eighty employees under me. Blue-collar workers. How can this engineer manage these eighty blue-collar workers? [They] can’t manage, so human relations are most important”.

G4: “But I think it was very effective that people from the sector and managers attended the classes with additional courses because you can talk to them about anything. You can ask anything in your stream. They guide you, they become a reference”.

G7: “Let me tell you a little more about our university: technical trips to the factory were not done very often. It would be much better if this was done more often”.

3.4.7. Comparison by Gender

Given that there were five male and three female participants, more of the comments were made by male participants. There were some gender differences. In particular, regarding negative elements, male participants mentioned process management, timing, and unclear drafts more frequently whereas female participants mentioned preparing a presentation more frequently. Regarding positive elements, male participants were more satisfied with the interviews whereas the female participants mentioned learning by experience more often. Table 2 summarizes the expressions used most frequently by each gender.

Table 2.

Comparison by gender.

Overall, both male and female participants mentioned the difficulty of implementing the 10/20/70 leadership model. While women more frequently recommended creating more development awareness to promote employee development, men tended to recommend 360-degree evaluations.

3.4.8. Comparison by Length of Employment

To compare the participants’ interview responses by length of employment, two groups were created: those working for 1–7 years and those working for 8 years and above. Regarding negative elements, participants in the first group, more frequently mentioned process management, timing, imposition, and inability to do one-to-one presentations, whereas participants in the second group only mentioned implementing the target development behavior. Regarding positive elements, those in the first group tended to mention learning by experience, raising awareness, and interviews, whereas those in the second group also mentioned similar interviews (one-to-one interviews, mentoring, and receiving feedback). In short, participants in both groups were positively affected by the interviews (mentoring, one-on-one interviews, and receiving feedback) and awareness raising.

Regarding ideas about what the company should do to promote employee personal development, more recent participants suggested creating development awareness and conducting 360-degree evaluations, whereas longer-serving participants suggested the company provide training. They also reported participating in personal development training and trying to stay up to date by watching videos and movies and reading books. Longer-serving employees also reported activities like practicing and reading books. Regarding the effects of the 10/20/70 model, more recent employees were more likely to say that it was difficult to implement, created understanding, was educational, and enabled learning by experience.

Regarding the contribution of university education to their work lives, more recent employees gave more comments. In particular, they reported that university had not contributed, although some acknowledged a moderate contribution in terms of perspective, human relations, and multifunctionality. Many of these participants also commented on what universities need to do. Table 3 presents the frequency of statements about the university contribution and suggestions for university processes according to the length of employment.

Table 3.

University contribution and processes according to length of employment.

As Table 3 shows, participants who have been working in the enterprise for less than eight years were more likely to comment (87.5%) on all questions asked, compared to 12.5% for the longer-serving participants.

A cloud representation of the codes formed in the analysis indicated that the participants were more likely to talk about the following ideas: learning by experience, interviews, raising development awareness, raising awareness, training applications, and 360 evaluation.

4. Discussion, Conclusions, and Contributions

This study reported on an intervention conducted with the ABC company to increase the development curves of white-collar employees while developing their presentation techniques. Data from the interviews with eight white-collar workers were analyzed and the findings were interpreted under six main themes.

First, the participants reported negative experiences about the performance process based on the company’s personal development competencies, particularly about the management of the process. Other negative elements included scheduling, inability to present, imposition, preparing a presentation, and unclear draft.

Second, the participants reported a number of positive elements, particularly the opportunity to learn and experience during the performance process. They saw this as a positive element that increases motivation by allowing them to remember and reinforce their skills. Regardless of the length of service, participants mentioned conducting interviews and raising awareness, including mentoring, one-on-one interviews, and feedback.

Regarding the third theme, the 10/20/70 rule, all participants except one said they applied the 10/20/70 rule. This is one of the informal learning models that the company wanted its employees to use while fulfilling their personal development goals. However, the participants found the model difficult to apply. This finding receives support from Zeman (2022) [35], who concluded that the effect of culture means that there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Johnson et al. (2018) [33] concluded that this rule can be more effective when used with other applications. In short, it was difficult for the participants to apply the 10/20/70 rule, so it may be more appropriate to try a different learning model in future interventions.

The fifth theme was university contribution. The participants generally did not believe that their university education contributed to their working life or changed their perspectives. Finally, the participants offered various suggestions in the sixth theme about what universities should do to improve their education programs. These included intensive practical training, more teaching on data collection and use and organization of technical trips, and internship incentives.

Regarding the effect of length of employment in the company, those working for 7 years or less tended to express more opinions on each subject. This result contradicts Tayfun and Catir (2013) [42], who reported that employees with a longer service life in the profession tend to be more vocal for the benefit of the organization.

Regarding gender effects, male participants tended to report more opinions. One reason for this is that there were more male interviewees. Participants of both genders frequently mentioned the difficulty of implementing the 10/20/70 leadership model.

These findings are supported by Lejenue et al. [24], who concluded that learning activities, especially informal learning techniques (such as self-learning), should be encouraged to maximize workplace learning effectiveness [24]. The participants in the present study also suggested that the company should create more intensive development awareness and conduct more regular 360-degree evaluations. These results are in parallel with Igudia (2022) [43], who argued that the right employees must be identified and sent for training in order to increase organizational performance. Each organization’s human resources (HR) department should also arrange appropriate training for the employees’ needs. This suggestion is also supported by Ybema et al. (2020) [12]. They identified two factors that contribute to the effectiveness of HR practices: the actual use employees make of implemented practices and their participation in designing these practices. Employee participation in designing HR practices was also related to higher satisfaction and employability. Therefore, it is critical for companies like ABC to ensure employee participation in designing training or employee development in order to increase satisfaction and employability. Similarly, according to Ullah et al. (2021) [2], one of the critical components of sustainable employability is encouraging human development through education, training, a positive work environment, fair pay, and a satisfactory corporate culture.

Future studies to evaluate such interventions can investigate different businesses using larger samples. One of the limitations of this study was the small sample size because the ABC company only allowed a few employees to be interviewed. Thus, future studies could expand the sample to provide more solidly grounded results. Researchers can also apply different learning models for both blue-collar and white-collar employees and measure the effectiveness of these models. Finally, future studies can evaluate strategies to promote the development of blue-collar employees.

Author Contributions

B.M.Ö.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, and visualization. U.B.G.: formal analysis, investigation, and review and editing. S.E.O.: resources, data curation, and original draft preparation. A.G.: project administration and supervision writing. F.M.S.: funding acquisition and writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Manisa Celal Bayar University, grant number 9.540 Turkish Liras.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Manisa Celal University and approved by the Manisa Celal Bayar University Social and Humanities Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (E.199180 and 20 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mingaleva, Z.; Shironina, E.; Lobova, E.; Olenev, V.; Plyusnina, L.; Oborina, A. Organizational Culture Management as an Element of Innovative and Sustainable Development of Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Ali, S.B.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. The effect of work safety on organizational social sustainability improvement in the healthcare sector: The case of a public sector hospital in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Jacobs, R.L. The influence of investment in workplace learning on learning outcomes and organisational performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hot, T.C. İşletmelerde Eğitim ve Geliştirme ile Bireysel ve Örgütsel Performans İlişkisi, Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Doğuş Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İstanbul. 2017. Available online: https://acikbilim.yok.gov.tr/handle/20.500.12812/605723 (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Memon, H.A.; Khahro, H.S.; Memon, A.N.; Memon, A.Z.; Mustafa, A. Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Employee Performance in the Construction Industry of Pakistan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M. Impact of training and development on employee job performance in Nigeria. Saudi J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, N.C. Job preferences of white collar and blue collar workers. Acad. Manag. J. 1975, 18, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. New technology and the class structure: The blue-collar/white-collar divide revisited. Br. J. Sociol. 1996, 47, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, B. In organizational management; white collar personnel job satisfaction and organizational performance relationship. Quantrade J. Complex Syst. Soc. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, R.; Cavaliere, L.P.L.; Sikandar, A.M.; Sulthana, A.; Jayalakshimi, J.; Koti, K.; Hat, D.N.; Christagbel, A.J.G. The effects of tools and rewards provided to white-collar and blue-collar workers and impact on their motivation and productivity. Product. Manag. 2020, 25, 967–984. Available online: http://repository.petra.ac.id/18979/ (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Geyikci, U.B.; Çınar, S.; Sancak, F.M. Analysis of the relationships among financial development, economic growth, energy use, and carbon emissions by co-Integration with multiple structural breaks. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybma, F.J.; Vuuren, V.T.; Dam, V.K. HR practices for enhancing sustainable employability: Implementation, use, and outcomes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 886–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeijn, J.H.; van Dam, K.; van Vuuren, T.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. Sustainable labour participation for sustainable careers. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers; De Vos, A., van der Heijden, B.I.J.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid, R.W.; Lindsay, C.D. The concept of employability. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V. Enhancing employability: Human, cultural, and social capital in an era of turbulent unpredictability. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, B.; Dysvik, A. Perceived investment in employee development, intrinsic motivation and work performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2009, 19, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacopoulou, P.E. Employee development through self-development in three retail banks. Pers. Rev. 2000, 29, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Waheed, A. Employee development and its affect on employee performance a conceptual framework. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 224–229. Available online: https://www.ijbssnet.com (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Quartney, H.S. Effect of employee training on the perceived organizational performance: A case study of the print pedia industry in Ghana. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 77–87. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234624369.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Guan, X.; Frenkel, S. How perceptions of training impact employee performance evidence from two Chinese manufacturing firms. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaga, A.; Imran, A. The effect of training on employee performance. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 137–147. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234624593.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Manuti, A.; Serafina, P.; Scardigno, F.A.; Giancaspro, L.M.; Marciana, D. Formal and informal learning in the workplace, a research review. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraut, M. Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 70, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejeune, C.; Beausaert, S.; Raemdonck, I. The impact on employees’ job performance of exercising self-directed learning within personal development plan practice. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1086–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamsomboon, N.; Skurtprommee, S.; Klinpratum, V. Creating employee working skills and performance through organizational training practices in ABC tire manufacturing company. RMUTT Glob. Bus. Account. Financ. Rev. 2020, 4, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Özsoy, E.; Gürbüzoğlu, E.Y. Beyaz yakalı çalışanlarda aranan becerilerin belirlenmesine yönelik bir araştırma. Int. J. Manag. Distrib. 2019, 3, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waner, K.K. Business communication competencies needed by employees as perceived by business faculty and business professionals. Bus. Commun. Q. 1995, 58, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, C. Longterm unemployment and the employability gap: Priorities for renewing Britain’s new deal”. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2002, 26, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, J.; Kaisara, G.; Yakobi, K.; Atiku, O.S. Exploring push and pull factors for talent development and retention: Implications for practice. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2020, 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczyk, K. Changes in the approach to employee development in organisations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 46, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clardy, A. 70-20-10 and the dominance of informal learning: A fact in search of evidence. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2018, 17, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, R. Debate: The 70:20:10 ‘rule’ in learning and development the mistake of listening to sirens and how to safely navigate around them. Public Money Manag. 2022, 42, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Blackman, A.D.; Buick, F. The 70:20:10 framework and the transfer of learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2018, 29, 83–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, W.M., Jr. Recasting leadership development. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 3, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, J. Culture Influences the 70-20-10 Adult Learning Model. St. Joseph’s Univ. Capstone Proj. Adv. Semin. 2022, 1–23. Available online: https://www.l-ten.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ZEMAN_ODL-785-Capstone-Project-Paper_April-28-2022-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Magaldi, D.; Berler, M. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. In Semi-Structured Interviews; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Swtizerland, 2020; pp. 1–5849. [Google Scholar]

- Altunışık, R.; Coşkun, R.; Bayraktaroğlu, S.; Yıldırım, E. Sosyal Bilimlerde Araştırma Yöntemleri SPSS Uygulamalı; Sakarya Yayıncılık: Sakarya, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kıral, B. Nitel bir veri analizi yöntemi olarak doküman analizi. Siirt Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2020, 15, 170–189. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/susbid/issue/54983/727462 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Luborsky, M.R.; Rubinstein, R.L. Sampling in qualitative research: Rationale, issues, and methods. J. Aging Res. 1995, 17, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Sosyal Bilimlerde Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2014; pp. 1–448. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.; Moser, T. The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. Int. Manag. Rev. 2019, 15, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tayfun, A.; Çatır, O. Örgütsel sessizlik ve çalışanların performansları arasındaki ilişki üzerine bir araştırma. İşletme Araştırmaları Derg. 2013, 5, 114–134. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=691144 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Igudia, O.P. Employee training and development and organisational performance: A study of small-scale manufacturing firms in Nigeria. Am. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2022, 5, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).