Abstract

The objective of this work was to evaluate the innovation processes in tourist destinations using the Quadruple Helix model and to develop guidelines for building innovation management strategies in the tourism sector for destination management organizations (DMO). The article identifies the drivers and barriers to innovation processes reported by entrepreneurs in the tourism industry in Poland. The analysis was carried out in relation to 218 enterprises of the tourism industry operating in destinations in large cities as well as in destinations in small towns and rural areas. The research was carried out using a diagnostic survey with elements of a telephone interview. The research confirmed the usefulness of the Quadruple Helix model for the assessment of innovation processes in tourist destinations. A relationship was observed between the level of development of innovation processes, the size of the tourist destination and the level of competitiveness of the tourist market in the destination. The study showed a significant variation in the spatial and geographical system, as well as between individual factors responsible for the innovation processes in a tourist destination. The influence of the market, including consumers, is a strong point of these processes. The barriers include poorly developed structures of cooperation between enterprises, DMO, scientific and research institutions, and civil society, as well as their participation in the innovation processes of tourist destinations. Final conclusions: it should be stated that the innovative processes in Polish tourist destinations are underdeveloped. They do not affect the development of tourism markets and the competitiveness of destinations.

1. Introduction

Innovation in the tourism industry is considered a strategic issue that enables both enterprises and regions to achieve growth and long-term development. The conducted research reflects a wide spectrum of problems with the implementation of innovative solutions faced by both tourism industry enterprises and destination management organizations. Previous literature reviews [1,2,3,4,5,6] indicate that two directions of research on innovation processes have been distinguished. The first one concerns the research on a tourist enterprise. The second direction, represented in the literature to a much lesser extent, concerns the environment of the enterprise, i.e., the environment of their activity [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

The innovation environment model is analysed in the Quadruple Helix system. It consists of four groups of factors: administration, management and politics (Public), universities, research institutes and other types of educational units (Academia), the service market, including enterprises and consumers (Industry), and non-governmental organizations (Civil society) [14]. Innovative processes are territorially rooted [15] and each destination builds its competitive advantages using its own resources of “territorial peculiarities” [16,17,18]. Differences between destinations result from complex interactions and evolutionary dynamics conditioned by management models, social, economic, institutional and political systems [15] and the number of involved entities operating in the innovation environment [19]. In addition, each of the systems has a different impact on the innovation processes [11]. The tourism management system and technology transfer institutions, research and development institutions, and information transfer institutions have the greatest impact [11]. It should be stated that in tourist destinations where scientific and research centres operate and many entities are involved in the innovation process, such environments have higher opportunities for the development of innovative processes. Research by Pikkematt and Peters [20] proves that higher innovativeness occurs in enterprises operating in large city environments, which are characterized by a higher level of development in the above groups of factors than that in smaller destinations. The aim of the article is to assess the innovation processes of tourist destinations using the Quadruple Helix model and to develop guidelines for building innovation management strategies in the tourism sector for destination management organizations (DMOs). The article identifies drivers and barriers to innovation processes reported by entrepreneurs in the tourism industry in Poland. The article formulated three research questions: Do enterprises operating in rural destinations have a lower innovation index than enterprises operating in large urban agglomerations? What activities, new products and services at the target level stimulate innovative development? What barriers limit the innovativeness of tourism enterprises at the destination level? The results of these studies reveal some implications for DMO and innovation-enhancing tourism policies.

The article has been divided into sections. The first section discusses the literature on innovation in tourism. The second section discusses the research methodology in detail. The third section presents an empirical discussion of the research results. The article ends with a discussion and final conclusions. Due to the demographic changes, a significant issue in the management of the peripheral regions economic centres.

2. Literature Review

Innovation is defined as novel services and products or new applications thereof [21]. It is also worth noting the perception of innovation as a way of creative thinking and implementing ideas, i.e., transforming advanced concepts and knowledge into unique and newly created solutions [22]. In the current study, the meaning of innovativeness has been adopted, in accordance with the latest manual of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from Oslo [23], as a novel or improved service or product (or a mix of services and products), which was created as a consequence of the application of expertise, on which novelty, usefulness, or value are based, was applied by the company and is considerably different from former products or processes within the business, and was offered to prospective consumers (product) or applied by the firm (process). The major differentiating characteristic of innovativeness is the application of expertise as the foundation of novelty, utility, and value [24]. In addition, an important distinguishing feature of innovation is its final effect recorded by companies, such as an increase in added value [25], reduction in service provision costs [26], increase in sales income, increase in employee productivity [27], increase in the number of customers, and achieving higher profits [28].

The conducted reviews of literature concerning the research in the field of tourism by Hajlager [1], Gomezelj [2], Marasco et al. [3], Pikkemaat et al. [4], Shin and Perdue [5], and Cao et al. [6] indicate that two directions of research on innovation processes have been distinguished. The first covers a wide spectrum of tourism enterprise research. The second direction, represented in the literature to a much lesser extent, concerns the environment of the enterprise, i.e., the environment of their activity studied, and has been conducted by Boschma [7], Pikkemaat i Weiermair [8], Svensson et al. [9], Zach [10], Panfiluk [11], Najda-Janoszek and Koper [12], and Pikkemaat et. al [13].

The review of research indicates that innovation in tourism is a driving force for the development of both businesses and tourist destinations [10,13]. The implementation of innovations is considered essential in building the competitive advantage of enterprises and regions [2,22,28,29,30,31,32,33]. On the other hand, innovative activity is forced on entrepreneurs through high market competition [34,35]. In addition, an important stimulator of innovative behaviour of enterprises is the development of companies [36], and the need for their survival in a competitive environment [37,38,39], concerning small companies in particular [39,40,41,42].

Innovations are created in creative knowledge environments, referred to as collaborative networks [43] within the Quadruple Helix system. Research shows that an important factor influencing the innovativeness of enterprises is the environment in which they operate. The probability of implementing innovations increases with the increase in the number of competitive companies among which the company operates [44]. In addition, studies by Divisker et. al. indicate that the probability of implementing innovations for companies operating in unfavourable environmental conditions, e.g., in the area of natural disasters, decreases by 12% as compared to companies operating in favourable environmental conditions [44]. It has been proven that companies that are faced with competition are 1.6 times more likely to implement innovations than those that do not operate in a competitive environment [42,45]. In addition, it has been proven that tourist destinations where companies create and implement innovations are able to develop more dynamically than those that do not have them and have limited adaptive capacity [46].

The implementation of innovations is related to the adaptation of the offer of tourist services to the constantly changing needs of customers [28,37,47]. There are many indications that they are necessary for survival in the industry [42,48,49,50,51]. Due to the category of implemented innovations, we can observe changes in the behaviour of the tourism market. Radical innovations (concerning products or processes), implemented with the use of new technologies or knowledge, contribute to the destruction or suppression of existing infrastructure and the rapid development of the tourism market [52]. The so-called sustaining innovations, improving the functioning of companies, include the improvement of products or processes with the use of existing technologies or knowledge focused on existing markets. They do not affect market changes, but compete with existing solutions on the existing terms [40,53,54,55]. Camison and Mantford-Mir [56] state that most of the effects of implemented innovations are recognizable only within the region, but they contribute to improving the situation of the economy in that region [25,53]. Particularly in peripheral areas, they accelerate economic catching up [41,48,57,58]. In addition, it has been proven that regions where enterprises create and implement innovations are able to develop more dynamically than those that are deprived of them and have limited adaptability [54].

Research conducted in the tourism and hotel industry in various regions of the world has shown that tourism enterprises are characterized by medium and low innovation, as evidenced by the dominance of implemented incremental and adaptive innovations [40,53,54,55,59]. Sundbo et al. [37] define these as secondary, incremental and definitely non-technological with the dominance of product innovations. Radical innovations in this sector are rare [52], with studies by Booyens and Rogerson [60] indicating that only ¼ of the surveyed companies implement original innovations with a different scope of the tourism market [53].

The model of the innovative environment emphasizes the interactions between economic entities, which are based on the search for common solutions and mutual learning. Innovative environment can be seen in both geographical and economic terms, according to Boschm [7]. It can be a barrier (e.g., by isolating the region: mountain areas, islands, areas of natural value) or stimulate innovative processes. It has been observed that there are complex interdependencies in the environment of operating entities between the size of the market, and the political, legal and instance systems [61]. This kind of an advantage is local in nature. It results from the level of development of the factors forming individual helices, i.e., highly specialized knowledge, the market of services, public institutions [62], including regional management and policies for innovation, including policy-stimulating innovation based on cooperation at the regional, national, and target level [1,58,63,64] as well as civil society [14], i.e., civil society organizations, consumers [65]. In addition, the differences between individual environments result from the dynamics of interactions between individual factors [61]. Literature research by Nunes et al. [15] proves that innovation in tourism is territorially rooted and is built on the resources found there, referred to as “territorial peculiarities”. It is integrated by the management model, knowledge base, and learning system as well as the regional economic and social structure, which must be the subject and subject to evolutionary dynamics. Each territory builds its territorial cohesion according to objectives and resources. Differences between tourist regions result from evolutionary dynamics conditioned by management models, social, institutional and political systems [15]. In addition, each of the entities has a different impact on innovation processes [11]. It has been proven that, apart from the tourism management system, innovation processes in the region are strongly influenced by technology transfer institutions, research and development institutions, and information transfer institutions [11], together with the activity of tourist clusters [66] and their cooperation with local governments [67].

The innovation management system in the region should function on the basis of regional innovation strategies of the tourist region and funding programs for innovative activities in tourism. Its task should be to create conditions for cooperation between science, academia, as well as business and management systems. Within this system, there should be a flow of knowledge and information about the needs of customers in the tourism sector and the latest innovations. This system should foster cooperation between the scientific and research sectors and the enterprises [11]. The role of public entities in the field of tourism is to determine the optimal configuration of competitive advantages in relation to the region [68] and the implementation of innovation policy [69].

From the point of view of a tourist destination, significant differences are observed between tourism activities in destinations located within rural areas and tourism activities in destinations located within cities [8]. Companies operating in smaller destinations face competitive disadvantages, including low economies of scale and scope, minimal potential for diversification and innovation, and limited access to capital markets [70,71]. Research shows that the probability of implementing innovations decreases by 12% for companies operating in unfavourable environmental conditions, e.g., in the area of natural disasters and areas with difficult access (mountain areas) [44]. In addition, an important issue is the tourist attractiveness of the environment. Enterprises operating in an environment with high tourist attractiveness implement, on average, more innovations (1.66) per year than enterprises operating in an environment with lower tourist attractiveness (below the average 1.08) according to Krizaj et al. [55]. Innovative activity is also not fostered by operating in tourist areas subject to strong seasonality. It is one of the strongly limiting factors due to the alternation of peak and decline periods and the related negative economic, environmental or social effects [72]. This is due to the strong dependence of income from, for example, winter tourism. The dependence of the implementation of innovations on the environment in which enterprises operate is also indicated by studies of enterprises operating in forest areas in New Zealand and Italy. Business owners and forest managers have been shown to be willing to embrace change, make better use of emerging opportunities, and introduce tourism innovations. They also recognize the profitability dimension of innovation. The implemented tourism and recreation innovations in these areas turned out to be a success. They have gained the support of entrepreneurs, which has a positive impact on the prospects for innovation development. It has been proven that due to the specificity of the area in which enterprises operate, innovations should be in line with the best practices in the field of sustainable management of local forests, which would also contribute to raising awareness of environmental issues. In the conclusions, the authors indicate the need to direct innovation towards more environmentally sustainable solutions, which means that recreational facilities should be built on a smaller scale [44]. Studies in naturally valuable Polish regions indicate that activity in such areas may also be limited as a result of objections of environmental protection institutions, or unfavourable policies of the municipal authorities regarding the implementation of innovations, according to Jaremen et al. [68].

In Polish conditions, tourism develops within the settlement network of urban and rural areas. Tourist products in rural areas are built with the use of valuable natural resources, animate and inanimate nature, and often occupy over 40% of the area of these areas. Research shows that innovative products in rural areas are built on exclusive “rural resources”, including mountains [73,74], farms, local cultures [75], and natural values that are unavailable in other tourist destinations. Differences in business activities are, firstly, due to the fact that firms have to manage limited resources and capacities [76,77,78]. Secondly, companies operate in the absence of appropriate development policies [78] and supporting infrastructure, such as accommodation, catering or transport [79]. Numerous research results regarding the measurement of innovativeness of enterprises in rural areas indicate that the introduction of new product and service offers has a positive impact on a company’s financial results [80]. Innovative offerings help these companies gain market share, improve service quality, increase productivity, reduce costs [78,81], and increase employment [82]. In this way, innovative tourism products and processes implemented in tourism enterprises can bring a double benefit to these companies, simultaneously increasing their revenues, reducing costs and increasing productivity. Innovativeness has also been linked to the growth and overall competitiveness of agritourism enterprises [22]. In addition, offering innovative tourism services increases the number of visits, length of stay, and satisfaction of tourists staying in rural areas [78]. Implementing innovations in technology-based tourism services operating in rural areas, such as online booking, facilitates planning for tourists [83,84] and increases their willingness to visit again [81]. Some studies also indicate that innovations implemented in rural areas have a direct impact on the economic and sustainable development of these areas [85,86,87,88]. However, Hjalager et al. [77] point to the weaknesses of tourism enterprises operating in rural areas, which consist in the lack of innovation.

It is recognized that building exclusive tourist products based on intangible assets in rural areas should be implemented within formal and informal business cooperation networks [13,89]. The results of literature research conducted by Madanaguli et al. [90] show that some researchers point to the fact that innovations are implemented through cooperation within a network [91,92,93]. However, Hjalager et al. [77] point to the weaknesses of tourism enterprises operating in rural areas, which result from the lack of innovation.

Conducting this analysis enables the formulation of the following research results:

H1.

The environment of destinations in large urban agglomerations, where there is high competition, is a stimulus for innovative activities.

H2.

The low rate of novelty of innovations introduced to services in the tourism sector is influenced by the low level of use of highly specialized knowledge.

3. Materials and Methodology

The empirical research involved a multi-sector analysis of companies within the tourist industry, analysing the scope of innovative activity in the years 2019–2021. The choice of businesses for the inclusion in the study was made in accordance with the PKD classification of Polish Economic Activity [94]. The study included groups of entities belonging to the tourism industry, providing the following services: accommodation, catering, transport, cultural, sports and recreation, as well as travel agencies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the scope of services in the tourism sector.

Consequently, based on statistical data from the Central Statistical Office, the Local Data Bank (GUS, BDL) [95], the structural scope of tourist service providers was ascertained and classified using voivodships, within which business activity is registered. To prevent any inaccuracies related to the constraint on research entities resulting from highly aggregated data contained in the Central Statistical Office, BDL [95], Divisekera, Nguyen [44], the data concerning entities, contact information and phone numbers were gathered on the basis of websites prior to beginning the research. On the basis of the web pages, a brief characterization of the company’s range of services and its activity was made, as well as customer assessments of innovation pertaining to the company’s activities. This was the basis on which enterprises were selected for this research.

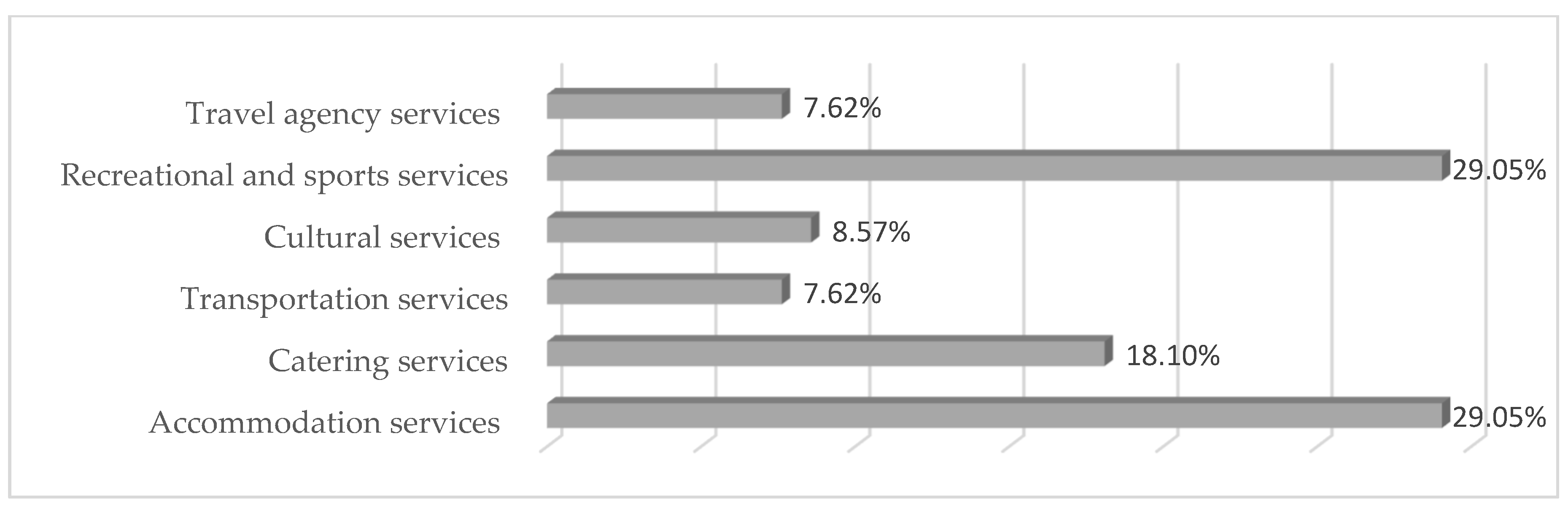

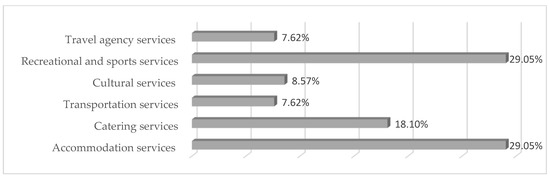

The material for this research was collected with the use of the diagnostic survey method enhanced with interview elements. The research tool was an interview questionnaire, and the research was conducted using the CATI technique. The pilot studies were performed in the period between May and June 2019, and the questionnaire was subsequently verified. In the period from April to November 2020, basic research was carried out. In total, 131 structured interviews were caried out. The rate of return (defined as the ratio between the number of people agreeing to be interviewed and the number of interviews conducted, including the refusal to take part in an interview) was at the level of 8%. In June 2021, another round of research was carried out. A total of 110 interviews were conducted in the second round of research. The research was commissioned to an independent company. In total, 242 companies participated in the study. The results were selected, and the enterprises whose answers had extreme outliers or were missing were removed. Ultimately, 218 enterprises were analysed. In the surveyed group, all entrepreneurs declared the implementation of at least one innovation. The group consists of 29.05% accommodation and recreation service providers and 18.10% catering service providers. Other service providers include cultural service providers (8.57%), as well as tourist transport service providers and travel agencies, each representing 7.62%. The structure of tourist services provided by the respondents is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of services provided by the surveyed enterprises, N = 218.

Next, the entities were divided according to the spatial and geographical environment of their activity. According to Hjalager et al. [77] and Pikkemat and Peters [20] rural areas were considered as unfavourable for the development of innovative processes. The EUROSTAT method, used by the Central Statistical Office in Poland, was used to divide the spatial and geographical environments. This method divides the areas of administrative units (commune, poviat) according to the degree of urbanization. A rural area is an area of an administrative unit where the population density does not exceed 100 people per square kilometre. The literature also recognizes broader classifications where, in addition to the population density criterion, attention is given to factors such as proportional share of employment in agriculture and access to infrastructure and services [96,97]. In this study, the area of the poviat was adopted as the classification unit. This criterion made it possible to distinguish 115 entities operating in rural areas, including 39 entities operating in small towns with a population of up to 25,000 people, and 103 entities operating in cities with a population of 25,000 and more in urban areas. The classification made it possible to distinguish three groups of entities operating in different spatial and geographical environments:

A total of 103 entities operating in large and medium-sized cities in urban areas where the degree of urbanization exceeds 100 people per 1 km2.

In total, 39 entities operating in small towns in rural areas, where the degree of urbanization does not exceed 100 people per 1 km2.

Lastly, 76 entities operating in villages in rural areas.

The analysis of the research material was carried out using the analysis of the % share in the structure of entities from each of the separated areas, the weighted average and the Pearson’s index. Calculations of the novelty scale of the implemented innovations were made using the weighted average. The values of the innovation novelty scale, defined in words, were transformed into a numerical scale, where the value 5 was assigned to a radical innovation, and the value 1 to an innovation consisting in improving the existing solution in the enterprise. The verbal description of the category of innovation novelty and the assigned numerical values are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Novelty scope of the applied innovations.

The reasons for the diversification of innovativeness of individual tourist destinations were examined based on the model of the innovative environment in the Quadruple Helix system. The level of development of factors forming individual helices was assessed by analysing the involvement of entities in activities undertaken at the stage of innovation implementation. The management system performance was assessed by measuring cooperation.

The group of factors responsible for innovation processes in a tourist region was distinguished:

Academic (knowledge acquisition):

- cooperation with highly specialized knowledge institutions. The variable in this category is: cooperation with scientific institutions [62].

- analysis of proprietary and employees’ knowledge; this category is described by activities in the field of creating innovations by the owners of these innovations themselves, collecting information from family and employees, including by combining various sources of knowledge, e.g., research from universities, information from companies, information from R&D, etc. [62].

Management:

- cooperation in a network of entrepreneurs, universities, industry organizations, local governments (e.g., clusters) [1,58,63,64].

Industry:

- market and competition analysis: this category includes the introduction of innovations that are available on the market, as well as gathering information about competition in the field of implemented innovations and implementing innovations that constitute a response to changing market needs.

- cooperation with environment institutions: this category is defined by activities in the implementation of innovations, such as cooperation with various entities within the supply chain, cooperation with other companies through the exchange of employees and cooperation within partner companies, as well as through employee training.

- analysis of the needs of consumers, recipients of services, when implementing innovations; their compliance with customer needs and their satisfaction is analysed, e.g., by conducting customer surveys, etc., analysing customer opinion with the use of, e.g., Facebook, Instagram, etc. The usefulness of innovations is tested by customers, consumer market and opinion research on purchased goods and services are used [14].

Civil society:

- cooperation with social and consumer organizations [14,65].

The results are presented according to the percentage of the number of indications.

4. Research Results

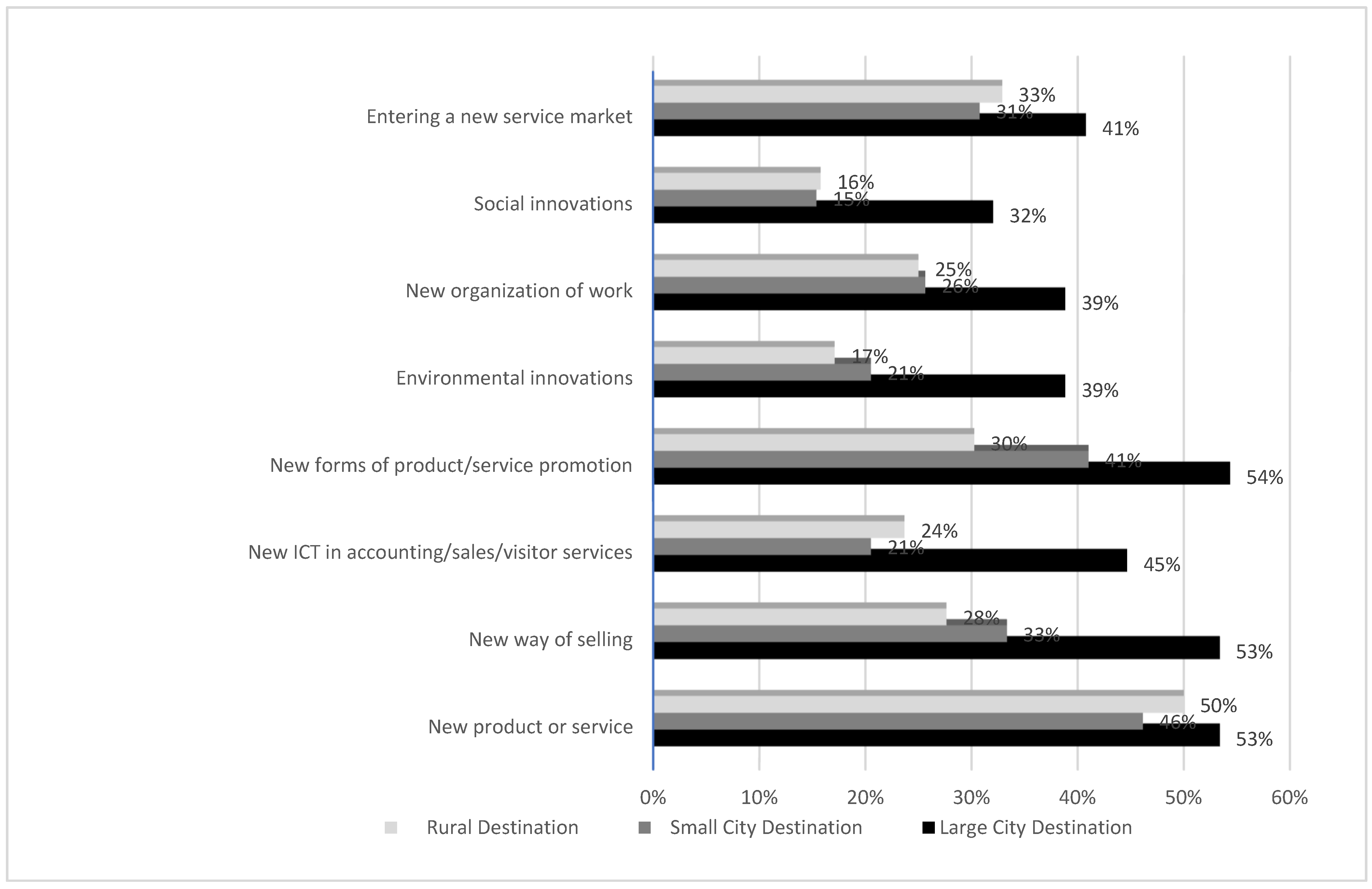

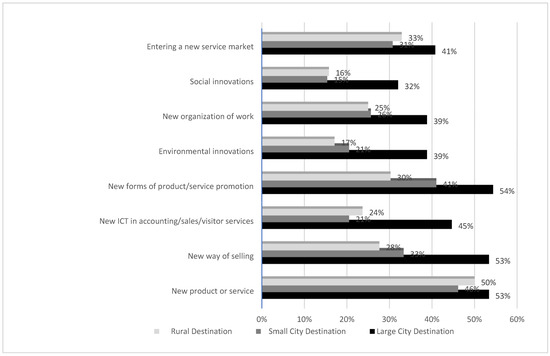

The analysis of the research results shows that a significantly higher percentage of entities operating in cities implement innovations, both in the case of product and process innovations (Figure 2). In the case of implementing product innovations, the advantage of entities operating in medium and large cities over entities operating in rural areas is small, 3%. In the case of process innovations, this advantage reaches about 20%. This means that, on average, 20% fewer entrepreneurs operating in rural areas implement process innovations than entrepreneurs operating in urban areas. On average, only about 25% of entities operating in rural areas implement innovations related to entering a new service market (32.89%), organization of service sales (27.63%), marketing activities (28.95%), ICT technology (23 0.68%) and work organization (22.37%). However, the analysis of enterprises operating in urban areas shows that, on average, about 50% of entrepreneurs implement process innovations, innovations related to entering a new service market (40.78%), organization of service sales (52.43%), marketing activities (54 0.37%), ICT technology (43.69%) and work organization (38.83%), respectively. It was also observed that in most types of implemented process innovations, the number of entities implementing innovations decreases along with the decrease in the population of the area in which they operate.

Figure 2.

Types of innovations implemented by tourism enterprises by type of tourist destination, N = 218.

The dependence between innovation implementation and tourist destination, according to the Pearson index, has been confirmed (Table 3). Dependence between innovation implementation, by type of innovation, and tourist destination, according to the Pearson index, has been confirmed (Table 4).

Table 3.

Dependence between innovation implementation and tourist destination, according to the Pearson index, N = 218.

Table 4.

Dependence between innovation implementation, by type of innovation, and tourist destination, according to the Pearson index, N = 218.

The investigation of the scope of novelty of the introduced innovations indicates the dominance of streamlining and adaptive innovations, with the dominance of adapting innovations commonly found in the tourism industry. The weighted average of the scope of innovativeness of implemented innovations does not exceed 3 points. This relationship occurs both in the implementation of product innovations (the weight of implemented innovations is 2.67 for enterprises operating in large cities, 2.44 in medium-sized cities and operating in rural areas 2.61) and process innovations (the weight of implemented innovations is 2.67 in large cities, 2.70 in medium-sized cities and 2.92 for the ones operating in rural areas respectively). A slightly higher scale of novelty characterizes innovations concerning the use of forms of promotion in small towns (3.13) and in rural areas in the use of new forms of sales (3.19), ICT technologies in accounting/sales/guest service (3.19) and activities related to entering a new service market (2.34) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The scale of novelty of implemented innovations.

The analysis of the answers of the respondents regarding the importance of activities for the innovation of tourist services shows that they consider undertaking activities in the field of the quality of the tourist offer as the most important (above 4 points). Then, entrepreneurs take action to diversify the tourist offer (the scale of importance exceeds 3.5 points) and only in the third place they indicate innovations for which there are no substitutes on the tourist market, i.e., radical innovations (below 3.5 points). These priorities make it possible to partially explain the scope of innovativeness of the implemented innovations. Firstly, they take actions aimed at increasing the quality of services, which explains the large percentage of incremental innovations involving the improvement of existing solutions. Secondly, they differentiate the offers, among which the offers that are new to the organization, but common in the industry, are dominant, which is indicated by the scale of novelty of innovation, which does not exceed 3 points. The third measure is the implementation of radical innovations (the scale of importance below 3.5 points) (Table 6). This is closely related to the small percentage of entities that declared the implementation of radical innovations (Table 7). In large city destinations, 9% declared the implementation of a radical product innovation, while 8% declared the implementation of process innovations. A slightly higher percentage of entities implemented radical product innovations, 11% and 13% in disadvantaged areas, respectively, and radical process innovations, 7 and 14%, respectively (Table 7).

Table 6.

The importance of activities for the innovativeness of tourist services.

Table 7.

Share of entities implementing radical innovations in the structure of the respondents.

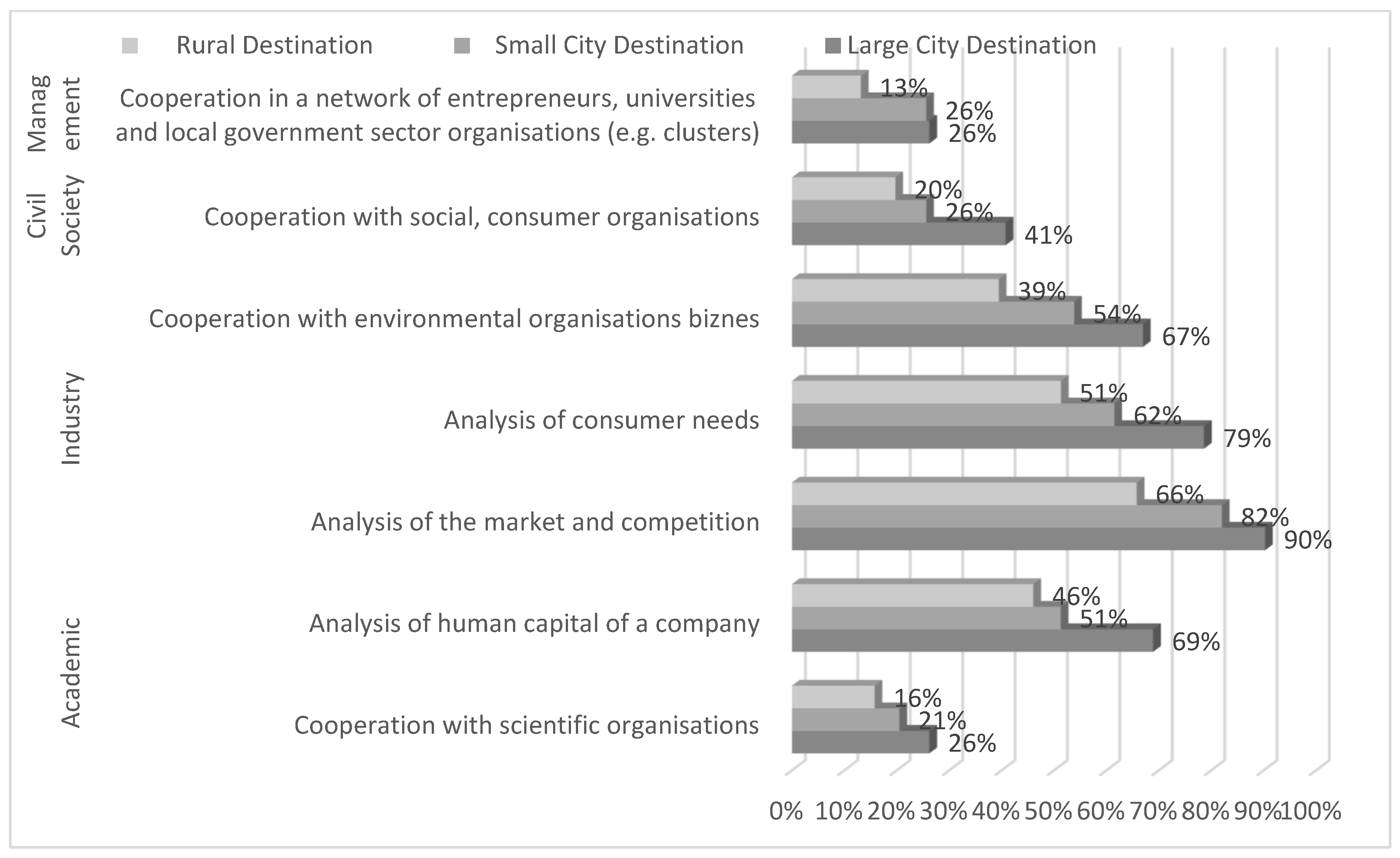

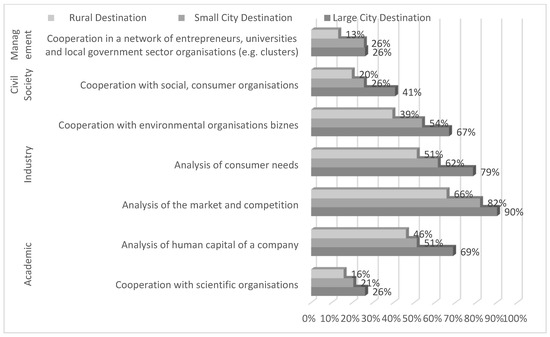

Four categories of the Helix of the innovation environment model were examined* (Figure 3). It showed significant differences both in the spatial and geographical arrangement as well as differences between individual factors.

Figure 3.

Categories of activities undertaken by enterprises when implementing innovations.

The analysis of the category of factors related to highly specialized knowledge shows that enterprises are primarily based on using the potential of their own knowledge and the knowledge of their employees: activities in this area are declared by 69% of entrepreneurs operating in tourist destinations of large cities, and 51 and 46% of entrepreneurs operating in rural tourist destinations. Their innovative activities are based on cooperation with highly specialized knowledge institutions, 26 and 16% of entities, respectively.

In the group of categories of factors related to the services market, the highest number of entrepreneurs base their innovative activities on the analysis of the market and competition, with 90% in tourist destinations of large cities and 66% of entrepreneurs operating in tourist destinations in rural areas. An equally large group of entrepreneurs undertake activities related to the analysis of the needs of consumers of tourist services. Such action is declared by 79% of entrepreneurs operating in tourist destinations in large cities and 51% of entrepreneurs operating in tourist destinations in rural areas. A total of 67% of entrepreneurs operating in tourist destinations in large cities and 39% of entrepreneurs operating in tourist destinations in rural areas see a chance for the development of innovativeness of the enterprise as a result of cooperation with the environment.

A very small number of enterprises indicate taking actions in the category of factors reflecting the activities of the management system. In total, 26% of entities operating in large city destinations and 13% of entities operating in rural destinations declare cooperation in a network of entrepreneurs, universities, local governments and industry organizations.

Cooperation with social organizations is developed at a slightly higher level, with 41% of entities operating in large city destinations and 20% of entities operating in rural destinations declaring cooperation with social and consumer organizations.

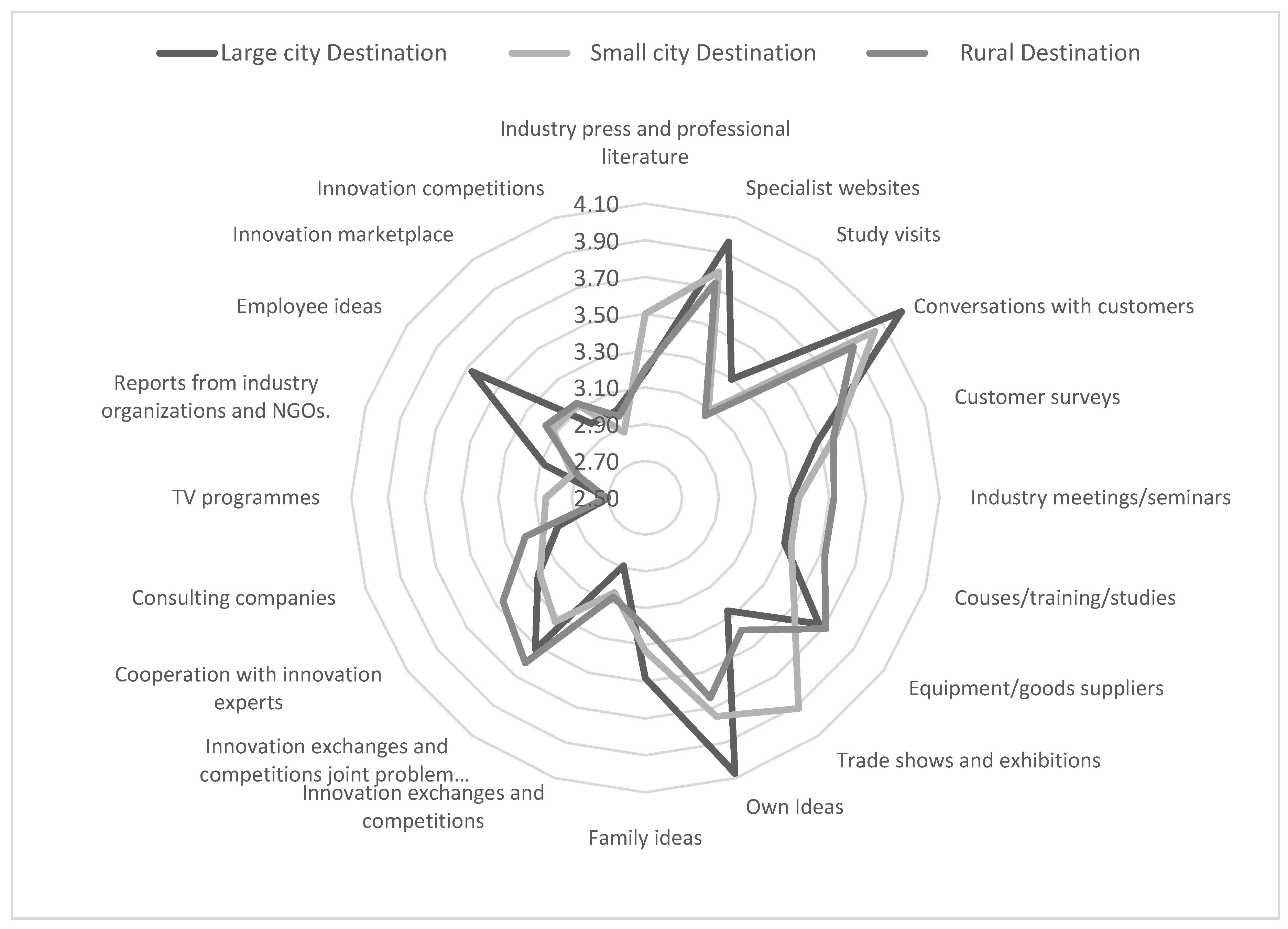

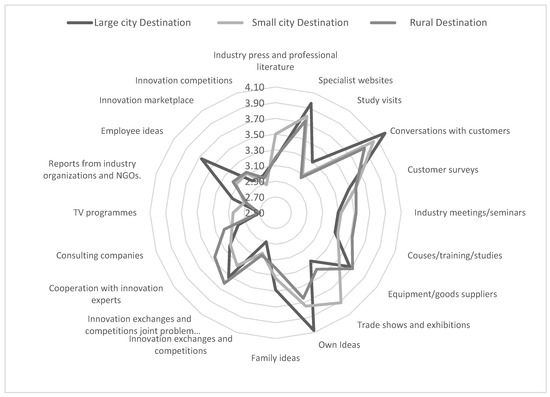

The source of information on innovations in relation to enterprises operating in destinations in large cities are conversations with clients (4.22 importance points), own ideas (4.07 importance points) and specialized websites (3.96 importance points). In small town destinations, these are conversations with clients (3.97 importance points), specialized websites (3.93 importance points), trade fairs (3.92 importance points), and own ideas (3.75 importance points). In rural destinations, these are conversations with clients (3.90 importance points), specialized websites (3.73 importance points), fairs (3.92 importance points), and own ideas (3.75 importance points) (Figure 4). The respondents, regardless of the type of tourist destination, use the same sources of information about innovations in most cases. Specialist sources with elements of influence of specialist knowledge, such as innovation exchanges, innovation competitions, cooperation with innovation experts, consulting companies, seminars/trainings and studies, are of little importance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sources of information about innovations.

The results indicate the following weaknesses of the innovative system of a tourist destination:

- low level of cooperation with scientific institutions in the field of transfer of highly specialized knowledge;

- dominance of own knowledge and employees’ knowledge in innovative activities;

- the dominant share of innovations aimed at increasing the quality of services provided and diversifying the tourist offer commonly available on the market of tourist services;

- low level of influence of public institutions (management system) on stimulating innovation processes in the region by pursuing a policy based on creating cooperation at the regional, national and local level;

- low level of civil society participation in innovation processes in destinations;

- dominance of the impact of the services market environment on innovative processes taking place in enterprises, including poorly diversified sources of information on innovations and low importance of sources of specialist knowledge.

These weaknesses were observed in all types of tourist destinations: to a lesser extent in destinations in large cities, and more so in rural areas.

5. Discussion

The analysis of tourism entities in terms of the spatial and geographical environment of their activity showed a relationship between the number of entities implementing innovations and the spatial and geographical environment of their activity. This relationship occurs, in particular, in process innovations. In most categories of implemented process innovations, the number of entities implementing innovations in unfavourable environmental conditions, i.e., in rural areas, decreases by 25% on average in relation to the number of entities operating in large urban agglomerations. This is a much more significant decrease than the studies indicate [44]. They obtained an indicator that the probability of implementing innovations for companies operating in unfavourable environmental conditions decreases by 12% [44]. Therefore, one should agree with the results of Remoaldo et al. [98], which state that, from the point of view of tourism activity, significant differences are observed between tourism activity in rural areas and tourism activity in city destinations, and this research shows that this difference deepens with the increase in the size of a tourist destination. Therefore, it should be concluded that large urban destinations are characterized by higher innovativeness than rural destinations, which is consistent with the results of Pikkemet et al. [20], who indicate that urban environments have higher innovativeness than rural environments. Due to the category of innovation, the number of enterprises implementing product innovations is dominant. In this category, no significant difference was observed in relation to the spatial and geographical environment of their activity, which is consistent with the results of Sundbo et al.’s studies of companies in Denmark and Spain [37], and Poland [53], which indicate the dominance of implemented product innovations. Process innovations in large city destinations are dominated by a number of enterprises implementing marketing innovations and innovations in the implementation of new forms of service sales, which is consistent with the results of Jakob’s study in the Spanish Balearic Islands, which demonstrated the dominance of process innovations.

It can therefore be concluded that enterprises operating in large city destinations, where there is a greater number of entities and higher competition, are more innovative than entities operating in small city destinations and rural areas with lower competition. It is consistent with the results of [34,35], which indicate that high market competition forces the undertaking of innovative activities in order to survive in a competitive environment [37,38,39]. Therefore, one should agree with the conclusions of Diviseker and Nguyen (that the likeliness of introducing innovations is heightened by the increasing number of competitive businesses, in which a company operates [44]) and the conclusions of Pikkemet et al. [20] (that the environment in which a company operates can be a significant barrier to innovative activity). This study proves that the barrier in small town and rural destinations is 25% higher than in large city destinations.

As a result of the study of the scope of innovativeness of introduced innovations, a relationship between the scale of novelty and the size of the environment in which the tourist enterprise operates was observed. Tourism enterprises operating in large cities in each category of implemented innovations achieved a higher value of implemented novelties. The highest level of differences between the large city destinations and rural destinations were observed in the case of implementing new ways of selling and new forms of work organization, and implementing new ICT technologies in the business processes of the enterprise. However, the weighted average of novelty of implemented innovations on a scale of 1 to 5 of all surveyed enterprises does not exceed 2 points. This proves the dominance of incremental and imitative innovations, which consist in improving an existing solution (adaptive) or are new only for the organization. These results are in line with the results of the study [40,53,54,55,59] of Sundbo et al. [37], which showed that tourism companies are characterized by a medium and low scale of implemented innovations with dominance of incremental and adaptive innovations [98]. The research conducted on Polish enterprises in tourist destinations of various sizes allows for the conclusion that the environment in the geographical and economic sense is a barrier to the implementation of innovations. These results are consistent with those of Boschm [7]. These entities may not react to market changes and may not undertake external cooperation [7].

Research on the factors of innovativeness of a tourist destination showed significant differences both in the spatial and geographical system, as well as between individual factors. Out of the four examined categories of the innovation environment, a high level of development of activities related to the analysis of the services market was observed. The innovative process of enterprises is influenced by tools such as analysis of competition, analysis of consumer needs and cooperation with the environment in which enterprises operate. It should be stated that such a detailed penetration of the tourism market in terms of:

- needs of consumers testifies to taking actions related to adapting the offer of tourist services to the constantly changing needs of customers. This is in line with the research results [1,28,37];

- observation of competition proves that evaluation changes are being made in the enterprise in order to survive in a competitive environment, which is consistent with the research results [25,28,37], and maintain its competitive position, which is consistent with the research results [34,35], in which the authors state that innovative activity is forced on entrepreneurs by high market competition;

- cooperation with entities from the external environment testifies to the actions aimed at the development of companies, which is consistent with the results of research [36], which indicate that innovative activity supports the development of companies.

The analysis of the category of factors related to highly specialized knowledge shows that enterprises rely primarily on using the potential of their own and employees’ knowledge. The development of cooperation with highly specialized knowledge institutions, such as scientific and research institutions or universities, was observed at a low and very low level. This is a factor that significantly limits the innovativeness of a tourist destination and the implementation of innovations with a large scale of innovation that may have a positive influence on the changes of the non-regional market and contribute to an increase in the competitive position of a tourist destination. These conclusions are confirmed by studies by Garcia and Calantone [52], which found that innovations created with the use of new technologies or knowledge are innovations with a high scale of innovation and contribute to the rapid development of the tourism market, and affect market changes, and thus changes in the competitive position of a tourist destination [52]. Their formation is attributed to network cooperation in a creative knowledge environment [43]. The so-called sustaining innovations, improving the functioning of companies using existing technologies or knowledge focused on existing markets, do not affect market changes, they only compete with existing solutions on existing terms, which is confirmed by research [40,53,55]. As the research shows, most of the effects of the so-called sustaining innovations are recognizable at the regional level. Camison and Mantford-Mir [56] state that the majority of the consequences of implementing innovations are recognizable solely within the region and they contribute to the improvement of the economy in the region [25,53]; in particular in outer areas, they contribute to the acceleration of economic catch-up [41,48,58]. Due to the fact that the preponderance of gradual and enhancing innovations created with the use of own knowledge was confirmed, it should be stated that the reason for the dominance of low-scale innovations is the lack of cooperation with highly specialized knowledge transfer institutions.

Similarly, a low level of cooperation of enterprises in the network was observed. This demonstrates the weaknesses of the management systems (DMO) that are responsible for conducting policies aimed at creating and coordinating the activities of business cooperation networks and stimulating collaborative innovation processes at the regional, national and destination level. [58,63,64,77]. These weaknesses significantly affect the creation of tourist products, including exclusive ones in rural areas, which should be implemented in formal and informal business cooperation networks. [13,89]. The low level of civil society involvement in the innovation processes of a tourist destination was also observed, which, as indicated by the research by Carayannis & Campbell [14], is a significant link in the network’s activity.

The study showed that in large city destinations, about ¼ of entities operate in networks that make up four categories of factors. Their functioning is influenced to the greatest extent by market processes and the knowledge that enterprises have. The governance system (DMO) and civil society have little impact on the functioning of the network. These networks are characterized by a low impact on innovation processes, because, as research by Panfiluk [11] indicates, the most effective influence on innovation processes is exerted by networks in which the tourism management system and technology transfer institutions, scientific and research institutions and information transfer institutions have dominance. Results of the presented studies entirely confirm Scuttari and Isetti’s recommendations [7].

6. Conclusions

The conducted research allowed for the achievement of the assumed goal, which was to assess the innovation processes of tourist destinations using the Quadruple Helix model and to develop guidelines for building innovation management strategies in the tourism sector for destination management organizations (DMOs). The article identifies drivers and barriers to innovation processes reported by entrepreneurs in the tourism industry in Poland. The analysis was carried out in relation to tourism industry enterprises operating in destinations in large cities and destinations in small towns and rural areas. These hypotheses were positively verified.

In the course of the research, it was proved that there is a relationship between the number of entities implementing innovations and the spatial and geographical environment of their activity. It has been proven that the environment in the spatial and geographical sense in which tourism enterprises operate is a barrier or a stimulator of innovation processes. This relationship occurs in process innovations and the scope of innovativeness of implemented innovations. The number of entities implementing innovations in unfavourable environmental conditions, i.e., in rural areas, decreases by 25% on average in relation to the number of entities operating in large urban agglomerations, and the scale of novelty decreases by 0.5 percentage points.

The local market is a strong point of the destination innovation processes. Firstly, a strong influence of customers as co-creators and stimulants of innovation in the tourism sector was observed, which ensures that offers are adapted to the needs of recipients of tourist services. Stakeholders of Polish tourist centers are highly aware of the high innovative potential of this group of recipients. Secondly, the innovation processes are stimulated by high market competition, which forces enterprises to undertake evaluation changes in the enterprise in order to survive in a competitive environment. Another stimulus is the cooperation with entities from the external environment, which is primarily aimed at the development of companies.

The results indicate the following weaknesses of the innovation system at the level of a tourist destination:

- dominance of the impact of the services market environment on innovative processes taking place in enterprises, including poorly diversified sources of information on innovations and low importance of sources of specialist knowledge;

- low level of cooperation with scientific institutions in the field of transfer of highly specialized knowledge, resulting in the lack of innovations characterised by a large scale of novelty and the lack of impact of innovative processes on the market and the competitiveness of the region;

- dominance of own and employees’ knowledge in innovative activity, which results in dominance of incremental and adaptive innovations with low impact on market processes and competitiveness of the region;

- low level of influence of public institutions (management system) on stimulating innovation processes in the region by conducting a policy based on creating cooperation at the regional, national and local level, which results in the lack of networks of entrepreneurs, universities, industry organizations, local governments (e.g., clusters);

- low level of civil society development in the regions and participation in innovation processes.

These weaknesses were observed in all types of tourist destinations: to a lesser extent in destinations in large cities, and to a greater extent in rural areas.

The results of this research reveal the following implications for DMO and tourism policy supporting innovation:

- stimulating partnership and networking in a tourist destination by building cooperation between the economy, science, public authorities, social and consumer organizations and centres of highly specialized knowledge transfer;

- strengthening social capital in a tourist destination by stimulating social activity, association, trust, openness and lasting network connections;

- building modern human capital, strengthening entrepreneurship and creativity as well as social activity;

- strengthening institutional links to support innovation and technology transfer in a tourist destination by establishing cooperation with research and development centres within the network;

- supporting the development of business environment institutions, financial, consulting and training services.

7. Scientific Contribution

This paper identifies three fields as new contributions to science. First, a conceptual framework was adopted to analyse the innovation processes of a tourist destination by applying the Quadruple Helix innovation environment model. This represents a significant contribution, taking into account the fact that up to that point the research into the innovativeness of tourist destinations was poorly recognized in the literature. The research was conducted by Boschma [7], Pikkemaat and Weiermair [8], Svensson at el. [9], Zach 10], Panfiluk [11], Najda-Janoszka and Kopera [12], and Pikkemaat et al. [13].

Secondly, the study showed that the innovativeness of a tourist destination is related to the size of the tourist destination and the level of competitiveness of the tourist market in the destination. This result is consistent with those of other studies, such as [34,35,37,38,39].

Thirdly, the empirical study provided a considerable amount of useful data on the level of development of the structure of the innovation system of a tourist destination. The study showed that the structure of innovation factors of a tourist destination defined in the Quadruple Helix model in the tourism industry evolves and shows significant variation both in the spatial and geographical system as well as between individual factors. The influence of the market has an important impact, including consumers and competitors. On the one hand, the impact of consumers is important because the innovation process is aimed at the recipients of services and meets their needs, which is consistent with the results of research [1,28,37]. On the other hand, competitors stimulate enterprises to undertake innovative activities, which is consistent with the research [34,35]. The development of the second link in the Quadruple Helix, i.e., the application of knowledge in the innovation process, shows significant weaknesses. Firstly, limiting the use of knowledge accumulated in the enterprise leads to the development of adaptive and incremental innovations that do not affect the changes in the competitive position of the destination, which is confirmed by the research conducted by Garcia and Calantone [52]. The so-called sustaining innovations, improving the functioning of companies using existing technologies or knowledge focused on existing markets, do not affect market changes; rather, they only compete with existing solutions on the existing terms, which is confirmed by research conducted by Panfiluk [53], Alsos et al. [40], Hoarau and Kline [54], as well as Krizaj et al. [55]. Most of the effects of such innovations are recognizable only at the regional level; as research by Camison and Mantford-Mir [56] shows, they contribute to the improvement of the economy in the region [25,53].

The weak link in the destination innovation processes is the use of highly specialized knowledge. This limits the innovation processes of a tourist destination and competition with other tourist destinations. These conclusions are confirmed by studies by Garcia and Calantone [52], which found that innovations created on the basis of cooperation with scientific and research institutions are characterized by a high rate of novelty, contribute to the rapid development of the tourism market, and have an impact on market changes and changes in the competitive position of a tourist destination [43,52]. The other two links of the tourist destination innovation system (DMO) and the activity of civil society show significant weaknesses, which are indicated by the low level of cooperation. These weaknesses in relation to management systems (DMO) were also identified in the research by Björk [63], Carlisle et al. [58], Hjalager [1,77], Rodríguez et al. [64], which show that the lack of a cooperation network directly affects the creation of specialized tourist products [13,89], and research by Carayannis and Campbell [14] in relation to cooperation with social and consumer organizations, which are a significant link in the network’s activity.

To sum up, it should be stated that innovative processes in Polish tourist destinations are poorly developed. They do not affect the development of tourism markets and the competitiveness processes between destinations. The most important activity should be building a network of cooperation between entrepreneurs, scientific and research institutions, destination management organizations, and social organizations.

8. Directions for Further Research

The conducted research indicates a new, little-recognized area of research concerning the innovativeness of tourist destinations. Research has shown that innovative processes in tourist destinations are poorly developed and the smaller the destination, the lower the innovative activity. Research should be carried out on the functioning network of cooperation, e.g., clusters, and the share and importance of individual links of the Quadruple Helix model and their impact on the innovativeness of destinations should be determined. A little-recognized direction of research is the impact of information sources used by entrepreneurs when implementing innovations on the scale of novelty of implemented innovations [99,100].

The outcome of the research may aid in the development of management schemes and strategies essential for launching innovative processes, especially within rural areas.

9. Research Limitations

This research also has its limitations. It should be noted here that the issue of sustainable development has not been addressed, i.e., does the type of destination in which enterprises operate affect the implementation of environmental innovations? There was also no analysis conducted concerning the impact of information sources on the category of innovation due to the scale of novelty or the effects achieved in the enterprise after the implementation of the innovation. The method of measuring the scale of the novelty of innovation in services should also be discussed further.

Funding

The research has been financed by the University of Technology Bialystok No: WZ/WIZ-INZ/2/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hjalager, A.M. A review of innovation research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomezelj, D.O. A systematic review of research on innovation in tourism and hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 516–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A.; De Martino, M.; Magnotti, F.; Morvillo, A. Collaborative innovation in tourism and hospitality: A systematic review of the literaturę. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2364–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Bichler, B.F. Innovation research in tourism: Research streams and actions for the future. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shina, H.; Perdue, R.R. Hospitality and tourism service innovation: A bibliometric review and future research agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.; Shi, F.; Bai, B. A comparative review of hospitality and tourism innovation research in academic and trade journals. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3790–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Constructing regional advantage and smart specialisation: Comparison of two European policy concepts. Ital. J. Reg. Sci. 2014, 13, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Weiermair, K. Innovation through cooperation in destinations: First results of an empirical study in Austria. Anatolia 2007, 18, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, B.; Nordin, S.; Flagestad, A. A governance perspective on destination development-exploring partnerships, clusters and innovation systems. Tour. Rev. 2005, 60, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, F. Partners and innovation in American destination marketing organizations. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfiluk, E. Management of the Tourist Region—Identification of the determinants of Innovation. Trans. Bus. Econ. 2021, 18, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najda-Janoszka, M.; Kopera, S. Exploring barriers to innovation in tourism industry—The case of southern region of Poland. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters Mike, P.; Chung-Shing, C. Needs, drivers and barriers of innovation: The case of an alpine community-model destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. Mode 3′ and ‘Quadruple Helix’: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 46, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sérgio Nunes, S.; Cooke, P. New global tourism innovation in a postcoronavirus era. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 1852534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.; Ritchie, J. Tourism, competitiveness, and social prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, J.; Wöber, K.; Zins, A. Tourism destination competitiveness: From definition to explanation? J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, M.; Danilda, I.; Torstensson, B.-M. Women resource centres—A creative knowledge environment of Quadruple Helix. J. Knowl. Econ. 2012, 3, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M. Towards the Measurement of Innovation—A Pilot Study in the Small and Medium Sized Hotel Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2005, 6, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. Teoria Rozwoju Gospodarczego; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A.; Krasnodębski, A. Respondents’ involvement in tourist activities at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Oslo Manual 2018: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation, 4th ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Organizacja Współpracy Gospodarczej i Rozwoju (OECD). Available online: https://stats.oecd.org (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Hall, C.M.; Williams, A.M. Tourism and Innovation; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Information technology for small and medium-sized tourism enterprises: Adaption and benefits. J. Inf. Technol. Tour. 1999, 2, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, A.; Sinclair, M.T.; Soria, J.A.C. Tourism productivity. Evidence from the United Kingdom. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1099–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, R.; Kowalewska, A.; Kowalewska, J. Impact of Implemented Innovations on Competiriveness of Tourism Companies in the Warminska-mazurskie viovodeship, Acta Sci. Pol. Oecon. 2020, 19, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, M.; Minniti, M. The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönte, W.; Falck, O.; Heblich, S. The Impact of Regional Age Structure on Entrepreneurship. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 85, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, M.; Karlsson, C. Who Says Life Is Over after 55? Entrepreneurship and An Aging Population; Centre of Excellence for Science and Innovation Studies; The Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kautonen, T.; Tornikoski, E.T.; Kibler, E. Entrepreneurial intentions in the third age: The impact of perceived age norms. Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 37, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Down, S.; Minniti, M. Ageing and entrepreneurial preferences. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenbacher, M.C.; Gnoth, J. How to Develop Successful Hospitality Innovation. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, P. Innovation and Tourism Policy. In Innovation and Growth in Tourism; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sundbo, J. Management of innovation in services. Serv. Ind. J. 1997, 17, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbo, J.; Orfila, F.; Sørensen, F. The innovative behaviour of tourism firms—Comparative studies of Denmark and Spain. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiermair, K. Product improvement or innovation: What is the key to success in tourism. In Innovation and Growth in Tourism; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.M. Tourism innovation; products, processes and people. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Alsos, G.A.; Eide, D.; Madsen, E.L. (Eds.) Innovation in tourism industries. In Handbook of Research on Innovation in Tourism Industries; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Román, J.A.; Tamayo, J.A.; Gamero, J.; Romero, J.E. Innovativeness and business performances in tourism SMEs. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 54, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Wood, E. The absorptive capacity of tourism organisations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 54, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, M.; Lindgren, M.; Packendorff, J. Quadruple Helix as a Way to Bridge the Gender Gap in Entrepreneurship: The Case of an Innovation System Project in the Baltic Sea Region. J. Knowl. Econ. 2012, 5, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisekera, S.; Nguyen, V.K. Determinants of innovation in tourism evidence from Australia. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Wood, E. Innovation in tourism: Re-conceptualising and measuring the absorptive capacity of the hotel sector. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Naipaul, S. Agritourism as a Catalyst for Improving the Quality of the Life in Rural Regions: A Study from a Developed Country. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorino, L.; Verma, R.; Plaschka, F.; Dev, C. Service innovation and customer choices in the hospitality industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2005, 15, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P.; Eriksson, R.H. Staying Power: What Influences Micro-Firm Survival in Tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Shaw, G.; Page, J.P. Understanding Small Firms in Tourism: A Perspective on Research Trends and Challenges. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsakal, Y.; Science, A. Strategic innovation: An empirical study on hotel firms operating in Antalya region. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 2, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson, J.; Orfila-Sintes, F. Hotel Innovation and Its Effects on Business Performance. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Calantone, R. Krytyczne spojrzenie na typologię innowacji technologicznych i terminologię dotyczącą innowacyjności: Przegląd literatury. J. Prod. Innow. Zarządz. 2002, 19, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Panfiluk, E. Innovativeness of Tourism Enterprises: Example of Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoarau, H.; Kline, C. Science and industry: Sharing knowledge for innovation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizaj, D.; Brodnik, A.; Bukovec, B. A Tool for Measurement of Innovation Newness and Adoption in Tourism Firms. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 16, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisόn, C.; Monfort-Mir, V.M. Measuring Innovation in Tourism from the Schumpeterian and the Dynamic-capabilities Perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Creative Outposts: Tourism’s Place in Rural Innovation. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, S.; Kunc, M.; Jones, E.; Tiffin, S. Supporting Innovation for Tourism Development through Multi-Stakeholder Approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, E.; Joppe, M. Developing a Tourism Innovation Typology: Leveraging Liminal Insights. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booyens, I.; Rogerson, C.M. Tourism innovation in the global South: Evidence from the Western Cape, South Africa. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.; Sousa, V. Scientific Tourism and Territorial Singularities: Some Theoretical and Methodological Contributions. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Inequality: Exploring Territorial Dynamics and Development; Ratten, V., Álvarez-Garcia, J., RioRama, M., Eds.; Routledge Frontiers of Business Management: London, UK, 2020; pp. 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode2 “to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P. The DNA of Tourism Service Innovation: A Quadruple Helix Approach. J. Knowl. Econ. 2014, 5, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Williams, A.M.; Hall, C.M. Tourism innovation policy: Implementation and outcomes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthing, J.; Sandén, B.; Edvardsson, B. New service development learning from and with customers. Int. J. Serv. Manag. 2004, 15, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowska-Niszczota, M. Clusters as instruments of implementation of innovation on the example of the tourist structures of Estern Poland. In Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2017; pp. 813–822. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska-Niszczota, M. Tourism Clusters in Eastern Poland—Analysis of Selected Aspects of the Operation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremen, D.; Gryszel, P.; Rapacz, A. Innowacje a atrakcyjność turystyczna wybranych miejscowości sudeckich. Acta Sci. Pol. 2010, 9, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Panasiuk, A. Fundusze Unii Europejskiej w Gospodarce Europejskiej; Wydwnictwo Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Peters, M. SMEs in tourism. Tour. Manag. Dyn. 2006, 2013, 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tejada, P.; Moreno, P. Patterns of innovation in tourism ‘Small and Medium-Size Enterprises’. Serv. Ind. J. Bus. Ventur. Serv. 2013, 33, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, J.M.M.; Fernández, J.A.S.; Martín, J.A.R.; Rey, M.S.O. Analysis of Tourism Seasonality as a Factor Limiting the Sustainable Development of Rural Areas. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 44, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Carrubi, D.; Currás -Móstoles, R.; Escrivá-Beltrán, M. Penyagolosa trails: From ancestral roads to sustainable ultra-trail race between spirituality, nature, and sports. A case of study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, D.; Culasso, F.; Giacosa, E.; Battaglini, L.M. Can livestock farming and tourism coexist in Mountain regions? A new business model for sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmi, P.; Lezzi, G.E. How authenticity and tradition shift into sustainability and innovation: Evidence from Italian agritourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forleo, M.B.; Palmieri, N. The potential for developing educational farms: A SWOT analysis from a case study. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2019, 25, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Østervig Larsen, M. Innovation gaps in scandinavian rural tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Ramos, D. Innovation in services: The case of rural tourism in Argentina. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2015, 51, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.C.; Chin, C.H.; Law, F.Y. Tourists’ perspectives on hard and soft services toward rural tourism destination competitiveness: Community support as a moderator. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Entrepreneurial behaviour, firm size and financial performance: The case of rural tourism family firms. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongma, W.; Lin, Y.T.; Leelapattana, W.; Cho, C.C. Environmental education and perceived eco-innovativeness: A farm visitor study. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 2017, 3, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, K.L.; Lin, P.M.C. Social entrepreneurs: Innovating rural tourism through the activism of service science. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossling, S.; Lane, B. Rural tourism and the development of internet-based accommodation booking platforms: A study in the advantages, dangers and implications of innovation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1386–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Mao, Z.; Wang, M.; Hu, L. Goodbye maps, hello apps? Exploring the influential determinants of travel app adoption. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coros, M.M.; Gica, O.A.; Yallop, A.C.; Moisescu, O.I. Innovative and sustainable tourism strategies: A viable alternative for romania’s economic development. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 504–515. [Google Scholar]

- Cosma, S.; Paun, D.; Bota, M.; Fleseriu, C. Innovation—A useful tool in the rural tourism in Romania. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Wei, F.; Zhang, K.H.; Gu, D. Innovating rural tourism targeting poverty alleviation through a multi-industries integration network: The case of Zhuanshui village, Anhui province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jamal, T. The co-evolution of rural tourism and sustainable rural development in hongdong, korea: Complexity, conflict and local response. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1363–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Park, A.; Kietzmann, J.; Archer-Brown, C. Beyond bitcoin: What blockchain and distributed ledger technologies mean for firms. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A.; Kaur, P.; Mazzoleni, A.; Dhir, A. The innovation ecosystem in rural tourism and hospitality—A systematic review of innovation in rural tourism. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 1732–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Maggioni, V. Managerial practices and operative directions of knowledge management within inter-firm networks: A global view. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Jimenez, D.; Martinez-Costa, M.; Sanz-Valle, R. Knowledge management practices for innovation: A multinational corporation’s perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, I. Knowledge networks as part of an integrated knowledge management approach. J. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 6, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polska Klasyfikacja Działalności Gospodarczej. Available online: www.biznes.gov.pl (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Bank Danych Lokalnych. Available online: www.bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Ocaña-Riola, R.; Sánchez-Cantalejo, C. Rurality index for small areas in Spain. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 73, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.A.; Carson, D.B.; Lundmark, L. Tourism and mobilities in sparsely populated areas: Towards a framework and research agenda. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 14, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoaldo, P.; Matos, O.; Freitas, I.; Pereira, M.; Xavier, C. An international overview of certified practices in creative tourism in rural and urban territories. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 1, 1545–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, N.; Landry, R. Sources of information as determinants of novelty of innovation in manufacturing firms: Evidence from the 1999 statistics Canada innovation survey. Technovation 2005, 25, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, P.; Doloreux, D.; Chamberlin, T. Innovation novelty and (commercial) performance in the service sector: A Canadian firm-level analysis. Technovation 2011, 31, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).