Measuring Sustainable Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship Orientation to Improve Tourist Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Lifestyle Entrepreneurs’ Definitions and Motivations

2.2. Main Approaches to the Theme

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

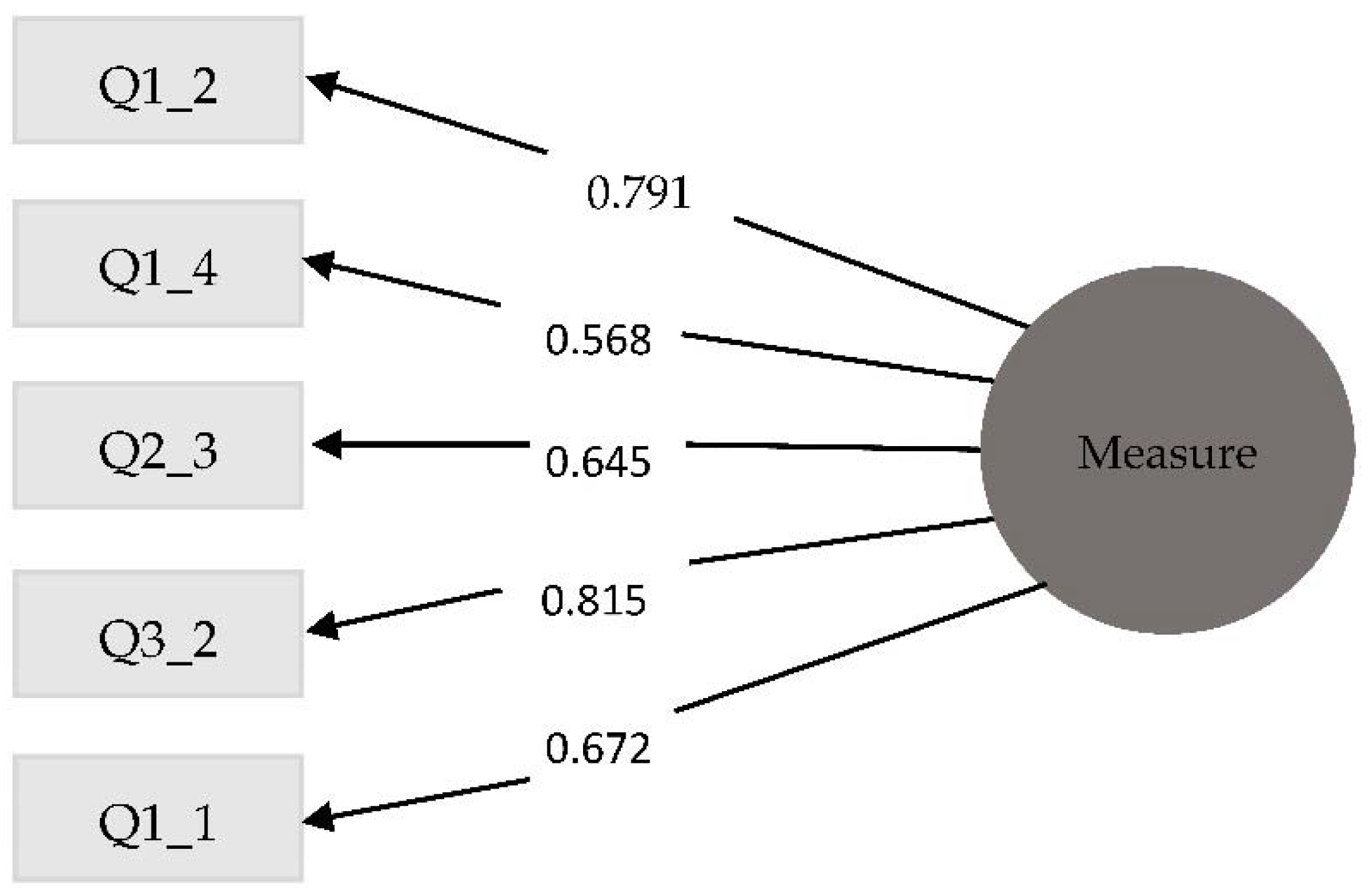

4.1. Measurement Analysis

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1_1 | 0.684 | ||

| Q1_2 | 0.757 | ||

| Q1_3 | 0.572 | ||

| Q1_4 | 0.629 | ||

| Q2_1 | 0.721 | ||

| Q2_2 | 0.555 | ||

| Q2_3 | 0.636 | ||

| Q3_3 | |||

| Q2_5 | 0.714 | ||

| Q3_2 | 0.678 |

4.2. Nomological Validity

5. Discussion

- A TLE is someone who cares about the environment and uses local resources.

- A TLE offers more genuine and different experiences due to local knowledge and contact with local communities.

- The TLE has a strong connection with the community, helping them by buying local products.

- The TLE offers a unique experience to tourists, through contact with the local community and activities.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dawson, D.; Fountain, J.; Cohen, D.A. Seasonality and the lifestyle “conundrum”: An analysis of lifestyle entrepreneurship in wine tourism regions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; Pérez-Pérez, M. Entrepreneurship and Family Firm Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of An Emerging Field. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Mattsson, S. Farm tourism in Sweden: Structure, growth and characteristics. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2002, 2, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.; Dias, A.; Patuleia, M.; Pereira, L. Financial Objectives and Satisfaction with Life: A Mixed-Method Study in Surf Lifestyle Entrepreneurs. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Farrell, H. Tourism entrepreneurs in Northumberland. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1474–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcketti, S.B.; Niehm, L.S.; Fuloria, R. An exploratory study of lifestyle entrepreneurship and its relationship to life quality. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2006, 34, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Schänzel, H. The Role of Children in Tourism and Hospitality Family Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I.; Doorne, S. ‘Staying within the fence’: Lifestyle entrepreneurship in tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilar, H.; Keskitalo, E.C.H. Tourism activity as an expression of place attachment–place perceptions among tourism actors in the Jukkasjärvi area of northern Sweden. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18 (Suppl. 1), S42–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blapp, M.; Mitas, O. Creative tourism in Balinese rural communities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1285–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Patuleia, M. Retaining tourism lifestyle entrepreneurs for destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Marques, G. Exploring Creative Tourism: Editors Introduction Richards. J. Tour. Consum. Pract. 2012, 4, 1–11. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/11687 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Dias, Á.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Patuleia, M. Developing poor communities through creative tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. Entrepreneurship research. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, M.J. Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources; Marsh Publications: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kuratko, D.F. Entrepreneurship theory, process, and practice in the 21st century. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2011, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, M.S.; Méndez, M.T.; Galindo, M.Á. The effect of social, cultural, and economic factors on entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1496–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solvoll, S.; Alsos, G.A.; Bulanova, O. Tourism Entrepreneurship—Review and Future Directions. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Okumus, F.; Wu, K.; Köseoglu, M.A. The entrepreneurship research in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, H. Role Shifting Between Entrepreneur and Tourist: A Case Study on Dali and Lijiang, China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yachin, J.M. The entrepreneur–opportunity nexus: Discovering the forces that promote product innovations in rural micro-tourism firms. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Silva, G.M. Lifestyle Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Rural Areas: The Case of Tourism Entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2021, 31, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Simonetti, B.; Bakas, F.E. Developing Lifestyle Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Destinations. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 970005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, H.; Vareiro, L.; Mendes, R.; Sousa, B. Sustainability in Rural Tourism: The Strategic Perspective of Owners. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Lonik, K.A.T. Tourism growth and entrepreneurship: Empirical analysis of development of rural highlands. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.; di Domenico, M.L.; Miller, G. The nature of ethical entrepreneurship in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 65, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Silva, G.M.; Patuleia, M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Developing sustainable business models: Local knowledge acquisition and tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Rural tourism development in southeastern Europe: Transition and the search for sustainability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Patuleia, M.; Silva, R.; Estêvão, J.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Post-pandemic recovery strategies: Revitalizing lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021, 14, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Torres, F.J.; Lopez-Torres, G.C.; Schiuma, G. Linking entrepreneurial orientation to SMEs’ performance: Implications for entrepreneurship universities. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3364–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Hakkarainen, K.; Lonka, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Entrepreneurship as a twenty-first century skill: Entrepreneurial alertness and intention in the transition to adulthood. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkranikal, J.; Morrison, A. Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Tourism: The Houseboats of Kerala. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2002, 4, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idziak, W.; Majewski, J.; Zmyślony, P. Community participation in sustainable rural tourism experience creation: A long-term appraisal and lessons from a thematic villages project in Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1341–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredvold, R.; Skålén, P. Lifestyle entrepreneurs and their identity construction: A study of the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism in the city. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; Echtner, C.M. Social capital and tourism entrepreneurship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1570–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Fink, M.; Lang, R.; Muñoz, P. Place attachment and social legitimacy: Revisiting the sustainable entrepreneurship journey. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2015, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Buhalis, D. Hospitality entrepreneurs managing quality of life and business growth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2014–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, G.; Xu, H. Impact of Lifestyle-Oriented Motivation on Small Tourism Enterprises’ Social Responsibility and Performance. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Kraus, S.; Peters, M.; Steiner, J.; Cheng, C.F. Entrepreneurship in tourism firms: A mixed-methods analysis of performance driver configurations. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.; Molina, A. Collaborative networked organisations and customer communities: Value co-creation and co-innovation in the networking era. Prod. Plan. Control. 2011, 22, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P.; Dias, Á.; Patuleia, M. The impacts of tourism on cultural identity on lisbon historic neighbourhoods. J. Ethn. Cult. Stud. 2021, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, I.; Marcher, A.; Volgger, M.; Pechlaner, H. The special characteristics of tourism innovation networks: The case of the Regional Innovation System in South Tyrol. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Fink, M.; Kibler, E. Understanding place-based entrepreneurship in rural Central Europe: A comparative institutional analysis. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 32, 204–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; van de Ven, A. Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvedalen, J.; Boschma, R. A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, E.; Vanneste, D. Tourism networks unravelled; a review of the literature on networks in tourism management studies. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 15, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Vittersø, J.; Dahl, T.I. Value Co-creation significance of tourist resources. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B. The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S. A Research in Relating Entrepreneurship, Marketing Capability, Innovative Capability and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Tourism entrepreneurship research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, P.; Moreno, P. Patterns of innovation in tourism “Small and Medium-size Enterprises”. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnogaj, K.; Rebernik, M.; Hojnik, B.B.; Gomezelj, D.O. Building a model of researching the sustainable entrepreneurship in the tourism sector. Kybernetes 2014, 43, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastroberardino, P.; Calabrese, G.; Cortese, F.; Petracca, M. Sustainability in the wine sector: An empirical analysis of the level of awareness and perception among the Italian consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2497–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Shaw, G.; Page, S.J. Understanding small firms in tourism: A perspective on research trends and challenges. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, L. Commodification and perceived authenticity in commercial homes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. The Effect of Estimation Methods on SEM Fit Indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2020, 80, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: Do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aileen Boluk, K.; Mottiar, Z. Motivations of social entrepreneurs. Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 10, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Purchase of local products within the rural tourist experience context. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.P.; Veloso, C.M.; Sousa, B.B.; Valeri, M.; Walter, C.E.; Lopes, E. Managerial Practices and (Post) Pandemic Consumption of Private Labels: Online and Offline Retail Perspective in a Portuguese Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Creative Outposts: Tourism’s Place in Rural Innovation. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athula Gnanapala, W.K. Tourists Perception and Satisfaction: Implications for Destination Management. Am. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 1, 7–19. Available online: http://www.aiscience.org/journal/ajmrhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Veloso, C.M.; Walter, C.E.; Sousa, B.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Santos, V.; Valeri, M. Academic tourism and transport services: Student perceptions from a social responsibility perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items |

|---|

| A TLE is someone who has a tourism business and is looking for a different lifestyle to achieve a better quality of life. |

| A TLE is someone who cares about the environment and uses local resources. |

| A TLE offers more genuine and different experiences due to local knowledge and contact with local communities. |

| For the TLE, lifestyle, and quality of life are more important than profit and economic growth. |

| The TLE’s choice of where to live is emotional because of the connection they have with it, namely by having a second home. |

| The TLE’s choice of where to live is emotional because of the connection they have with it, namely with their family. |

| The TLE is in places with quality social, environmental, and physical resources. |

| The TLE is in places with an attractive climate. |

| The TLE is in places surrounded by nature. |

| Some of the TLEs have their personal and professional lives concentrated in the same space. |

| The TLE has a strong connection with the community, helping them by buying local products. |

| The TLE seeks a balance between work and leisure. |

| The TLE works and lives in the same place, avoiding commuting |

| The TLE has a low level of education and little management experience. |

| The TLE seeks to have enough income to support themselves. |

| The TLE moves from place to place in search of the desired lifestyle. |

| The TLE offers a unique experience to tourists through contact with the local community and activities. |

| The TLE contributes to the development of poor communities through the development of tourism activities that generate employment and investment opportunities, among others. |

| The TLE tends to continue their activity even after retirement. |

| Some of the TLEs develop their work with ancient arts and materials they find in the space they have occupied, for example, tiles, ceramics, and ancestral art. |

| The price to be paid for these activities or products is a symbolic and fair value. |

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent type | ||

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 75 | 36.9 |

| 26–35 | 30 | 14.8 |

| 36–45 | 47 | 23.3 |

| 46–55 | 39 | 19.2 |

| 56–65 | 9 | 4.4 |

| >65 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Level of Education | ||

| 9th Year | 15 | 7.4 |

| Secondary School | 66 | 32.5 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 98 | 48.3 |

| Master’s Degree | 24 | 11.8 |

| Residence Area | ||

| North Region | 3 | 1.5 |

| Centre Region | 30 | 14.8 |

| Lisbon | 158 | 77.8 |

| Alentejo | 5 | 2.5 |

| Algarve | 2 | 1.0 |

| Açores | 2 | 1.0 |

| Madeira | 1 | 0.5 |

| Job Area | ||

| Tourism | 37 | 18.3 |

| Psychology | 8 | 3.9 |

| Restaurants | 5 | 2.5 |

| Management | 11 | 10 |

| Education | 9 | 4.4 |

| Other | 133 | 60.9 |

| Code | Items |

|---|---|

| Q1_1 | A TLE is someone who cares about the environment and uses local resources. |

| Q1_2 | A TLE offers more genuine and different experiences due to local knowledge and contact with local communities. |

| Q1_3 | The TLE’s choice of where to live is emotional, because of the connection they have with it, namely by having a second home. |

| Q1_4 | The TLE’s choice of where to live is emotional, because of the connection they have with it, namely with their family. |

| Q2_1 | The TLE is in places with an attractive climate. |

| Q2_2 | TLE is at places surrounded by nature. |

| Q2_3 | The TLE has a strong connection with the community, helping them by buying local products. |

| Q2_4 | The TLE works and lives in the same place, avoiding commuting. |

| Q2_5 | The TLE has a low level of education and little management experience. |

| Q3_2 | The TLE offers a unique experience to tourists, through contact with the local community and activities. |

| Code | Items added from Zatori et al., 2018 |

| Q4_1 | In a tourist experience, I value being able to enjoy the presence of people |

| Q4_2 | In a tourist experience, I value a pleasant environment |

| Q4_3 | During the tourist experience, I value being able to interact |

| Q4_4 | Interactions during a tourist experience are enriching |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antunes, M.; Dias, Á.; Gonçalves, F.; Sousa, B.; Pereira, L. Measuring Sustainable Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship Orientation to Improve Tourist Experience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021201

Antunes M, Dias Á, Gonçalves F, Sousa B, Pereira L. Measuring Sustainable Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship Orientation to Improve Tourist Experience. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021201

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntunes, Mariana, Álvaro Dias, Francisco Gonçalves, Bruno Sousa, and Leandro Pereira. 2023. "Measuring Sustainable Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship Orientation to Improve Tourist Experience" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021201

APA StyleAntunes, M., Dias, Á., Gonçalves, F., Sousa, B., & Pereira, L. (2023). Measuring Sustainable Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship Orientation to Improve Tourist Experience. Sustainability, 15(2), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021201